Abstract

Dementia is a risk factor for epilepsy. While seizures have a well-established association with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), their association with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is not established. We utilized the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centers’ Uniform Data Set (NACC-UDS V1–3) to analyze occurrence of seizures in DLB and seizure occurrence associations with mortality. We excluded subjects with conventional seizure risk factors. Seizure occurrence was noted in 36 subjects (2.62%) out of 1376 subjects with DLB. Among 500 subjects with pathologically confirmed DLB, seizure occurrence was documented in 19 (3.8%) subjects. Half of the subjects had onset of seizures three years before or after DLB diagnosis. Two-year mortality for subjects with DLB with seizures was high at 52.8% but no increased risk was noted as compared with subjects with DLB without seizures. More prospective and long-term longitudinal studies are needed to clarify relationships between DLB, seizure occurrence, and risk of increased mortality.

Keywords: Dementia with Lewy bodies, Seizures, Epilepsy, NACC, Mortality

1. Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is one of the commonest types of dementia, after Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia [1,2]. Core clinical criteria include fluctuating cognition with variations in alertness and attention, visual hallucinations, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, and parkinsonism [3]. Transient episodes of unresponsiveness are considered a supportive clinical criterion [3]. Epileptic phenomena are considered one of the many possible etiologies for some of the paroxysmal clinical features [4]. Isolated case reports of concurrent seizures and probable DLB highlighted improvements in clinical symptoms of DLB with seizure treatment, suggesting underlying hyperexcitability of neurons to be one of possible common patho-physiological mechanism [5–7]. Seizures are difficult to diagnose in patients with DLB because of the clinical features of fluctuating cognition and syncope due to autonomic dysfunction, which can present similar to seizures.

Dementia is a risk factor for seizures and epilepsy [8]. Multiple studies demonstrated higher incidence and prevalence of seizures and epilepsy in subjects with AD compared with healthy elderly individuals [9,10]. A similar association between DLB and seizures has not been systematically explored. We used the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centers’ Uniform Data Set (NACC-UDS V1–3) to analyze seizure occurrence in DLB and its relationship to mortality.

2. Materials and methods

Data were derived from NACC-UDS V1–3, conducted between September 2005 and February 2019 (March 2019 data freeze). The NACC-UDS is a large multicenter prospective and standardized database collected from AD research centers (ADRCs) across the United States. This analysis used data from 37 National Institute of Aging (NIA)/National Institute of Health (NIH)-funded ADRCs. Each ADRC enrolls its subjects according to center-specific priorities. In general, most participants come from clinician referral, self-referral by patients or family members, active recruitment through community organizations, and volunteers who wish to contribute to research. Most centers also enroll volunteers with normal cognition. Therefore, this is not a population representative sample. National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centers data are publicly available (https://www.alz.washington.edu/).

Seizure occurrence is recorded by a single item in the NACC-UDS (question 4a (v1) or 4c (v2–3) on form A5 relating to subject health history). Seizure occurrence is further classified as follows: i) recent or active — seizures occurring within the last year or still requiring active management; ii) remote or inactive — seizures existed or occurred in the past (more than one year ago) or without active treatment; iii) absent, and iv) unknown. Assessment is based on self-report or on history obtained from informants, medical records, and/or enrolling clinician observations. Seizure type is not recorded as part of the subject health history in the questionnaire.

We included subjects for whom DLB was the primary presumptive etiology of dementia. We excluded subjects diagnosed as Parkinson’s disease dementia. We excluded subjects with a history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) or stroke, common seizure etiologies in the elderly [11]. We report the number of subjects with seizure occurrence among those who were diagnosed with DLB. We fit a logistic regression model to test the associations of seizure occurrence with age, gender, and race. The model adjusted for varying follow-up time among different subjects. We performed sample size calculations to investigate whether our findings were due to true underlying patterns or lack of power to find patterns. We looked at the coefficient for the gender variable and seizure occurrence outcome.

Within the dataset of classified subjects with DLB, we also examined subjects with neuropathological confirmation of DLB (indicated using a variable NACCLEWY in the data set) as a sensitivity analysis. Using this sample, we fit a similar logistic regression to test the association of seizure occurrence with age, gender, and race. We also examined the presence of neuritic plaques and tauopathy (indicated using variables NACCNEUR and NACCBRAA in the data set) within classified subjects with DLB.

To examine mortality, we fit a Cox proportional hazards model for survival time and seizure occurrence. We adjusted for age at diagnosis, gender, and race (whether subjects were white or not).

3. Results

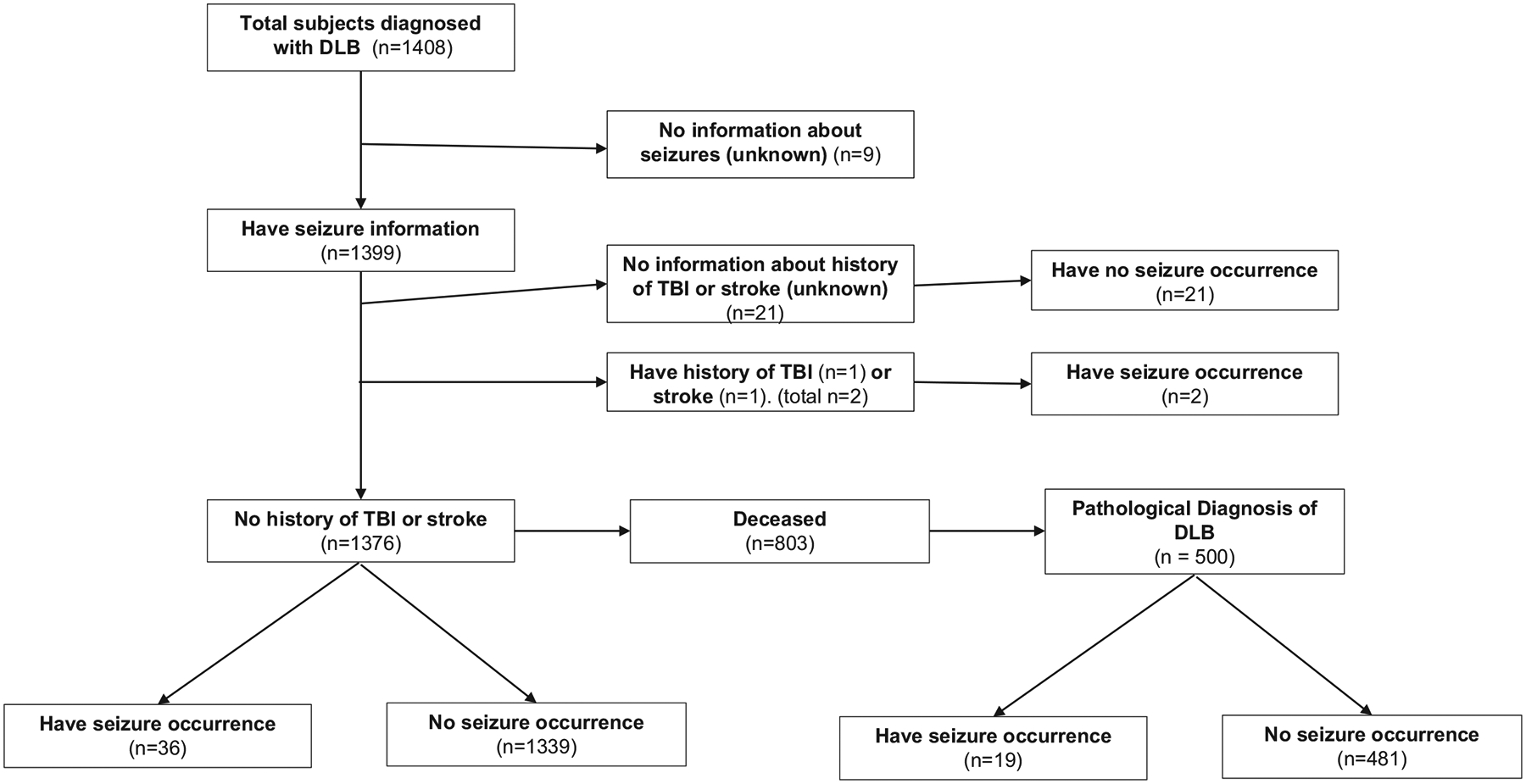

The NACC database contained 1408 subjects classified as DLB. Seizure information was available on 1399 subjects with DLB. Mean age at diagnosis of DLB was 74 years (range: 25 to 99 years; interquartile range (IQR): 68–80 years; median: 75 years; standard deviation (SD): 8.6 years). Twenty-three subjects with a history of TBI or stroke, or with incomplete information, were excluded. One subject with TBI and another subject with stroke had a diagnosis of seizures. The final analysis was performed on 1376 subjects with a mean of 1.9 follow-up years (median: 1.2, SD: 2.2).

Seizure occurrence was defined as having active seizures within the time range: three years prior to diagnosis of DLB to any time after diagnosis. The mean age of seizure occurrence was 76 years, and the range was 54 to 90 years. Among subjects with DLB classification, a total of 36 (22 males, 14 females) subjects had seizure occurrence (2.62%, 36/1376) (Table 1). Half of the subjects (18/36) reported their first ever seizure (active/recent seizure in an appointment preceded by remote/inactive seizure in the previous appointment) in the predefined time period. Two subjects had first seizure one year prior to DLB diagnosis, four at the time of diagnosis, and the rest up to 5 years after diagnosis.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study sample are reported for continuous (mean, standard deviation) and categorical variables (percent). The descriptive statistics are stratified by seizure occurrence (defined as having a seizure 3 years before Dementia with Lewy bodies diagnosis to any time after diagnosis) to identify any initial difference for seizure occurrence.

| No seizure occurrence (N = 1340) | Seizure occurrence (N = 36) | Overall (N = 1376) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age atdiagnosis (years, mean (SD)) | 74.09 (8.57) | 74.97 (9.57) | 74.12 (8.59) |

| Female (%) | 344 (25.7) | 14 (38.9) | 358 (26.0) |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 1192 (90.1) | 31 (91.2) | 1223 (90.1) |

| Black or African American | 79 (6.0) | 1 (2.9) | 80 (5.9) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 9 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (0.7) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Asian | 13 (1.0) | 1 (2.9) | 14 (1.0) |

| Multiracial | 29 (2.2) | 1 (2.9) | 30 (2.2) |

| Follow-up time (years, mean (SD)) | 1.95 (2.17) | 1.66 (2.02) | 1.95 (2.17) |

| Deceased (%) | 777 (58.0) | 26 (72.2) | 803 (58.4) |

Out of 1376 subjects, 803 were deceased and 582 had autopsies. Out of 582 subjects, 500 subjects had autopsy results that confirmed DLB. Among them, a total of 19 (11 males, 8 females) subjects had seizure occurrence (3.8%, 19/500) (Fig. 1). For both clinically diagnosed subjects and pathologically confirmed subjects, no association was found between seizure occurrence and age. Women had somewhat higher odds of seizure occurrence in clinically diagnosed DLB, but it was not significant (odds ratio (OR) = 1.88, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.92–3.86). Similarly, for subjects with pathologically confirmed DLB, women had a higher odds of seizure occurrence but not significant (OR = 2.18, 95% CI: 0.82–5.80). Based on power analysis, roughly 3300 subjects are needed to detect a significant signal for the effect of sex. Therefore, this null association might be due to inadequate statistical power.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of subjects with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).

Fifteen out of nineteen (79%) subjects with pathologically confirmed DLB with seizures had moderate or frequent neuritic plaques as compared with 303/481 (63%) of subjects with pathologically confirmed DLB without seizures. Thirteen out of nineteen (68.5%) subjects with pathologically confirmed DLB with seizures also had tauopathy (Braak stages III to VI) as compared with 357/481 (74.5%) of subjects with pathologically confirmed DLB without seizures. The chi-squared test of independence between presence of neuritic plaques or tauopathy and seizure occurrence was not significant, likely due to low power and small sample size.

Thirty-one out of 36 patients (86%) identified as white. For both diagnoses and pathologically confirmed subjects, no association was noted between seizure occurrence and ethnicity.

The two-year mortality rate for those with seizures was 52.8% (19/36), while the two-year mortality for those without seizures was 44.9% (601/ 1340). Overall mortality for available follow-up was 72.2% for those with seizure occurrence and 58% for those without seizures. Subjects with DLB with and without seizures did not differ for their mortality risk (hazard ratio (HR): 1.25, 95% CI: 0.83–1.9) after adjusting for age at diagnosis, gender, and race.

4. Discussion

In this analysis of the NACC-UDS database, we found seizure occurrence at relatively high frequency in both clinically diagnosed DLB (2.62%) and pathologically confirmed DLB (3.8%) compared with general population [12,13]. Half the subjects had new-onset seizures occurring three to five years around DLB diagnosis. We did not detect a difference in mortality between subjects with DLB with and without seizures.

The elderly have the highest incidence of seizures of any age group after infancy, reported to be 0.08 to 0.16% [12]. For elderly subjects with dementia, seizures occur at a rate 17 times higher than reference populations (16.8/1000 vs. 0.98/1000) [13]. The association between AD and seizures is well established [9], but less is known about associations between DLB and seizures.

4.1. Incidence and prevalence of seizures in DLB in literature and comparison with current study

Previous population and clinic-based studies noted wide variations in DLB incidence (0.5 to 1.6 per 1000 person-years) and prevalence (0.02 to 33.3 per 1000 person-years), likely due to suboptimal methods and difficulty in diagnosis of DLB [2]. Very few studies investigated seizure occurrence in subjects with DLB. A small number of single-center studies are published. In a 10-year single-center retrospective chart review study assessing clinical and neurophysiologic characteristics of patients with dementia and seizures, 9% of patients (77/879) were found to have seizures related to dementia. Five percent (4/77) were eventually diagnosed with DLB. Further subanalysis of this population was not described [10].

In another single-center dementia registry and retrospective chart review, 3.6% (63/1738) of patients were found to have seizures. After excluding patients with insufficient information, 13% (N = 5) of these patients had a diagnosis of DLB [14]. In a memory clinic study, two out of four patients with DLB had a history of seizures, but one patient had a childhood onset, and the other had a four year difference between memory loss and seizure onset [15]. In a large (N = 1846) retrospective analysis of seizures in different types of dementia, AD and DLB (N = 178) were found to have cumulative seizure probability in up to 15% of patients in 15 years of follow-up. The incidence of seizures in DLB was 5.1% [16]. In the same study, the cumulative seizure probability after two years of follow-up was around 1.5%, which compares favorably with a 2.6% occurrence after a median follow-up of 1.9 years in our study. Our study has the advantage of a much larger sample size of patients with DLB.

4.2. Association of age in patients with seizures and dementia

Prior studies showed conflicting information on age as a factor in patients with seizures and dementia. Some studies noted that younger age groups (<65 years) with dementia have higher risk of seizures, while others noted older age groups to have a higher risk of seizures [16–18]. Friedman et al. concluded that dementia severity, rather than age, is likely the relevant risk factor [9]. These studies mainly investigated AD, and DLB was not assessed specifically. However, Beagle et al. showed that in DLB, incidence of seizures was much higher after 69 years [16]. In our study, the onset of seizures was at a mean of 76 years, which is consistent with study by Beagle et al.

4.3. Relationship of seizure onset to onset of cognitive decline and dementia

Beagle et al. found seizure onset in the four years centered around the onset of cognitive decline for subjects with DLB [16]. Similarly, Sarkis et al. reported that in patients with non-AD dementia, seizures either preceded or followed the onset of cognitive symptoms within a 4.5-year period [10]. Similar to these studies, we used a three-year cutoff before DLB diagnosis for inclusion and found that half of the subjects had onset of seizures either three years before or up to five years after diagnosis.

4.4. Mortality

Association of mortality with seizures in dementia has not been studied extensively. A study assessing hospitalized elderly patients with seizures did not find dementia to be associated with mortality [19]. In a thesis analyzing Medicare beneficiaries from a single center, patients with AD and related disorders (ADRD) were divided into those with (3%) and without seizures. Those with ADRD and seizures had a significantly higher mortality rate (56%) than those with ADRD without seizures (36%) in a five-year follow-up period. Multivariable regression analysis showed that concurrent seizures and AD have a 2.4 higher risk of mortality even after adjusting for age, gender, and race [20] as compared with those with ADRD and without seizures. No previous studies specifically investigated mortality in patients with DLB and seizures. Our two-year mortality rate at 52.8% is very high and likely higher than what would be seen in patients with concurrent AD and seizures at the same time point. We also did not find an association with age, gender, or race. We likely observed a higher mortality rate because patients with concurrent DLB and seizures are older than patients with concurrent AD and seizures [16]. A longer follow-up period or larger sample might discern significant differences in mortality between those with and without seizures.

4.5. Neuropathology and neuronal hyperexcitability

Morris et al. described aberrant cortical excitability and seizures in a transgenic murine model of DLB. In this model, α-synucleinopathy was associated with depletion of neuronal calbindin protein in the dentate gyrus [21]. In the same study, analogous Electroencephalogram (EEG) findings were reported in subjects with DLB and dentate gyrus calbindin ribonucleic acid (RNA) was depleted in postmortem samples from subjects with DLB. Similar decreases in dentate gyrus calbindin expression was described in nondementia-related temporal lobe epilepsy in humans [21].

Dementia with Lewy bodies is frequently misdiagnosed as AD, and there can be considerable overlap with AD pathology (plaques and tangles) in DLB [22]. In the NACC dataset, nearly 86% diagnosed as probable DLB had pathology consistent with DLB. The accuracy of the diagnosis of DLB in this study is likely much higher than a Medicare or similar national database as all subjects were evaluated at ADRCs. However, we also found a majority of subjects (with or without seizures) to have significant neuritic plaques and tauopathy. It is likely that the different pathologies are contributing to epileptogenesis.

4.6. Strengths and limitations

Our study adds to the limited information available for DLB, seizures, and related mortality. While the large sample size of patients with DLB (manifold larger than previously described in the literature) is a strength of our analysis, this cohort might overrepresent the actual incidence and prevalence of seizures in subjects with DLB. Subjects in our dataset were referred to ADRCs, and it is possible that our sample includes subjects with more complex symptoms such as seizures. In addition, each ADRC contributing to NACC enrolls patients according to its priorities. The NACC subjects with DLB may not be representative of DLB occurring in the community. Other limitations include the difficulty of diagnosing seizures in the elderly in general and, as such, might be underdiagnosed. Lack of many seizure-related details in the NACC database, including types of seizures and EEG findings, inability to differentiate between myoclonus and seizures also limits further analyses and prevents confirmation of seizure diagnosis. We also did not report on the pattern of use of antiepileptic drugs in the study subjects.

5. Conclusions

We found a seizure occurrence frequency of 2.6% in a large sample of clinically defined DLB subjects from the NACC Uniform Data Set. In pathologically confirmed DLB, seizure occurrence frequency was higher at 3.8%. After adjusting for age at diagnosis, gender, and race, the mortality HR comparing subjects with seizure occurrence with those with no seizure occurrence was not significant, possibly due to the relatively low number of subjects with seizures. A larger sample, including more subjects with DLB with seizure occurrence, would provide enough power to evaluate whether there is a higher risk of death among subjects with DLB with seizure occurrence. Because of limitations of the NACC Data Set, our estimate of seizure occurrence frequency may be an overestimate. Larger, prospective studies are required to assess the true frequency, characteristics, and impact of seizures in DLB, and to compare seizures in DLB with seizures in AD.

Acknowledgment

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P30 AG062428-01 (PI James Leverenz, MD) P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P30 AG062421-01 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P30 AG062422-01 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI Robert Vassar, PhD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P30 AG062429-01(PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P30 AG062715-01 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

Rohit Marawar, Nicole Wakim, Roger Albin, and Hiroko Dodge have no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Rizzi L, Rosset I, Roriz-Cruz M. Global epidemiology of dementia: Alzheimer’s and vascular types. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:908915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hogan DB, Fiest KM, Roberts JI, Maxwell CJ, Dykeman J, Pringsheim T, et al. The prevalence and incidence of dementia with Lewy bodies: a systematic review. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43(Suppl. 1):S83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor JP, Weintraub D, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89:88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Briel RC, McKeith IG, Barker WA, Hewitt Y, Perry RH, Ince PG, et al. EEG findings in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:401–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Park IS, Yoo SW, Lee KS, Kim JS. Epileptic seizure presenting as dementia with Lewy bodies. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(230):e3 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tun MZ, Soo WK, Wu K, Kane R. Dementia with Lewy bodies presenting as probable epileptic seizure. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ukai K, Fujishiro H, Watanabe M, Kosaka K, Ozaki N. Similarity of symptoms between transient epileptic amnesia and Lewy body disease. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17:120–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia. 1993;34:453–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Friedman D, Honig LS, Scarmeas N. Seizures and epilepsy in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:285–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sarkis RA, Dickerson BC, Cole AJ, Chemali ZN. Clinical and neurophysiologic characteristics of unprovoked seizures in patients diagnosed with dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ramsay RE, Rowan AJ, Pryor FM. Special considerations in treating the elderly patient with epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;62:S24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Brodie MJ, Kwan P. Epilepsy in elderly people. BMJ. 2005;331:1317–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].DiFrancesco JC, Tremolizzo L, Polonia V, Giussani G, Bianchi E, Franchi C, et al. Adult-onset epilepsy in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60:1267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rao SC, Dove G, Cascino GD, Petersen RC. Recurrent seizures in patients with dementia: frequency, seizure types, and treatment outcome. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14: 118–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Baker J, Libretto T, Henley W, Zeman A. The prevalence and clinical features of epileptic seizures in a memory clinic population. Seizure. 2019;71:83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Beagle AJ, Darwish SM, Ranasinghe KG, La AL, Karageorgiou E, Vossel KA. Relative incidence of seizures and myoclonus in Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60:211–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Scarmeas N, Honig LS, Choi H, Cantero J, Brandt J, Blacker D, et al. Seizures in Alzheimer disease: who, when, and how common? Arch Neurol. 2009;66:992–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Romanelli MF, Morris JC, Ashkin K, Coben LA. Advanced Alzheimer’s disease is a risk factor for late-onset seizures. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:847–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].de Assis TM, Bacellar A, Costa G, Nascimento OJ. Mortality predictors of epilepsy and epileptic seizures among hospitalized elderly. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2015;73:510–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Andrade RA. The increased risk of mortality in elderly patients with epilepsy and dementias. In; 2015.

- [21].Magloczky Z, Halasz P, Vajda J, Czirjak S, Freund TF. Loss of Calbindin-D28K immuno-reactivity from dentate granule cells in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 1997;76:377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jellinger KA. Influence of Alzheimer pathology on clinical diagnostic accuracy in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2004;62:160 [author reply 160]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]