Abstract

Self-report measures are widely used for research and clinical assessment of adults with autism spectrum disorder. However, there has been little research examining the convergence of self- and informant-report in this population. This study examined agreement between 40 pairs of adults with autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers on measures of symptom severity, daily living skills, quality of life, and unmet service needs. In addition, this study examined the predictive value of each reporter for objective independent living and employment outcomes. Caregiver and self-report scores were significantly positively correlated on all measures (all r’s >0.50). Results indicated that there were significant differences between reporter ratings of daily living skills, quality of life, and unmet service needs, but no significant differences between ratings of symptom severity. Combining caregiver-report and self-report measures provided significantly higher predictive value of objective outcomes than measures from a single reporter. These findings indicate that both informants provide valuable information and adults with autism spectrum disorder should be included in reporting on their own symptoms and experiences. Given that two reporters together were more predictive of objective outcomes; however, a multi-informant assessment may be the most comprehensive approach for evaluating current functioning and identifying service needs in this population.

Lay Abstract

Self-report measures are frequently used for research and clinical assessments of adults with autism spectrum disorder. However, there has been little research examining agreement between self-report and informant-report in this population. Valid self-report measures are essential for conducting research with and providing high quality clinical services for adults with autism spectrum disorder. This study collected measures from 40 pairs of adults with autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers on measures of symptom severity, daily living skills, quality of life, and unmet service needs. Caregiver and self-report responses were highly associated with one another on all measures, though there were significant gaps between scores on the measures of daily living skills and quality of life. It is also important to understand how each informant’s responses relate to outcomes in the areas of employment and independent living. Using self-report and caregiver-report together better predicted outcomes for the adult with autism spectrum disorder than scores from either individual reporter alone. These findings show that there is unique and valuable information provided by both adults with autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers; a multi-informant approach is important for obtaining the most comprehensive picture of current functioning, identifying unmet service needs, and creating treatment plans. This research also highlights the importance of including and prioritizing self-report perspectives in shaping service planning.

Keywords: adults, assessment, autism spectrum disorder, self-report

Introduction

Upward of 500,000 children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are projected to enter adulthood within the next decade (Autism Speaks, 2013), reflecting the 163% increase in prevalence from 2002 to 2014 (Baio et al., 2018). The lifetime cost of care for an individual with ASD is estimated at upward of $1.4 million and $2.4 million for an individual with ASD and a comorbid intellectual disability. Due to the costs of housing, disability, and lost productivity from unemployment, the majority of these expenses are associated with adulthood (Buescher et al., 2014; Mandell & Knapp, 2012). Adult outcomes remain typically poor: many individuals with ASD need significant supports throughout adulthood, with a significant proportion living with family and many remaining unemployed (Howlin et al., 2014; Klinger et al., 2015; Shattuck et al., 2012). In a sample of adults with ASD, 54% of caregivers also reported that their adult son or daughter had unmet service needs (Dudley et al., 2019). Adult assessment instruments are critical to identifying these unmet service needs in order to create targeted support services and promote positive adult outcomes. However, there are few tools designed to capture the complex clinical presentation of ASD in adulthood (Bastiaansen et al., 2011).

The fastest growing subgroup within the ASD population is individuals without a comorbid intellectual disability (Baio et al., 2018), for whom self-report measures may be most appropriate. Unlike other types of adult psychopathology for which self-report measures are central to diagnostic practices, self-report has not traditionally been involved in the assessment of ASD. The assessment of ASD in adulthood is complicated by the range of cognitive ability that characterizes this population. For many adults with ASD, a caregiver-report is required. However, most adult psychopathology assessments were not designed to be used as a caregiver-report. The assessment of ASD in adulthood is also complicated by concerns that poor social insight may hinder this population’s ability to accurately report their own symptoms (Berthoz & Hill, 2005; Bishop & Seltzer, 2012; Mitchell & O’Keefe, 2008; Shalom et al., 2006). Though some contend that individuals with average intelligence are capable of accurately reflecting on inner experiences (Spek et al., 2010), research with adolescent with ASD indicates little convergence between self-report and parent interviews (Johnson et al., 2009; Mazefsky et al., 2011; White et al., 2012). Thus, there are concerns about the validity of both self-report and caregiver-report measures for adults with ASD.

Self-report measures are appealing for both research and clinical purposes, as they are typically inexpensive and easy to administer, and information from an informant is often unavailable or difficult to obtain for adults (Anderson et al., 1986; Volkmar et al., 2014). Moreover, it is important to include and prioritize the perspectives of autistic adults in shaping service plans.

However, there has been little research on the use of self-report measures in this population. Without greater knowledge on the utility of self-report for autistic adults, it is impossible to know if research relying on this method of data collection accurately reflects the target behaviors. If adults with ASD tend to under-report difficulties due to limited social insight, self-report may provide a conservative estimate of an individual’s true level of impairment, also making treatment planning and implementation more difficult. The possibility of under-reporting symptoms may result in failing to document clear need for adult services.

Critically, the limited research on adult self-report in ASD that is available tends to focus solely on correlational analyses without addressing the extent of discrepancies between self- and informant-reports; in other words, ratings provided by all reporters may be highly related on every item, but consistently higher or lower than one another. There is a fundamental knowledge gap regarding the domains in which self-report responses for adults with ASD are most likely to differ from informant-report and for which domains these discrepancies are largest. As adult service agencies, such as vocational rehabilitation, typically separate mental health and developmental disability-related services, this study focused on domains directly related to documenting need for and effectiveness of developmental disability services. Three domains are particularly relevant to assessment of service needs and treatment effectiveness in adulthood: symptom severity, adaptive behavior, and quality of life. Furthermore, it is essential to understand adult and caregiver perceptions of service needs, as identifying unmet needs is a first step in facilitating access.

Symptom severity

Accurate assessment of symptom severity is necessary for establishing diagnoses, as well as identifying areas of greatest impairment as targets for treatment planning and measuring treatment effectiveness. Because adults with ASD may have a limited awareness of their social and communicative impairments (Mitchell & O’Keefe, 2008), comparing adult self-report against the report of others may lend insight to the utility of a multi-informant approach in this population. Though multiple informants are recommended in the assessment of psychopathology in children and adolescents, as well as for adults with developmental and personality disorders (Barkley et al., 2011), there has been little research on convergence in these assessments for individuals with ASD. There is a striking lack of studies that directly compare informant- and self-report on the severity of symptoms associated with ASD (i.e. impairments in social communication and restricted interests and repetitive behaviors).

Adaptive behavior

Bishop-Fitzpatrick and colleagues (2016) found that better daily living skills were strongly associated with more positive normative outcomes (i.e. employment, independent living, and social engagement) and better objective quality of life (i.e. physical health, neighborhood quality, family contact, and mental health issues). Poor adaptive behaviors, including daily living skills, are a possible explanation for why adults with ASD often experience worse outcomes than would be expected based on cognitive ability alone, as even those with average to above average intellectual ability often demonstrate poor adaptive behaviors (Duncan & Bishop, 2013; Klinger et al., 2015). This gap between cognitive ability and adaptive behavior persists into adulthood and has been associated with comorbid mental health diagnoses (Kraper et al., 2017). Thus, assessment of adaptive behavior may be important to targeting skills needed for improved adult outcomes and for measuring developmental trajectory, as several authors have reported a plateau or decline in daily living skills in adults with ASD (Meyer et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2012). Difficulties with everyday activities, such as hygiene, cooking, or finances, make it significantly harder for an individual with ASD to achieve independence in adulthood (Duncan & Bishop, 2013). Because daily living skills are relatively concrete concepts, they have potential to be more easily targeted through supports and intervention than other domains, like symptom severity or intellectual functioning (Hume et al., 2009). However, it is possible that adults with ASD may self-report more daily living skills than they possess, making it difficult to demonstrate a “medical necessity” for services and to appropriately tailor services to their individual needs; consequently, a key opportunity to improve outcomes may be lost. Understanding the extent to which adults with ASD accurately report their adaptive behaviors and daily living skills will provide important information to researchers and clinicians seeking to understand and improve adult outcomes. Despite the extensive use of measures assessing adaptive daily living skills in public health practice, there has been little research on the reliability and validity of these measures for self-report in adulthood.

Quality of life

Improved quality of life is increasingly a primary goal of interventions and services for adults with ASD (Gerber et al., 2011), making accurate assessment of this construct critical for research and clinical practice. Measuring the validity of self-report is complex when it comes to quality of life, however. When quality of life is evaluated, one must take into account an individual’s subjective feelings about his or her life, as well as objective information about psychosocial factors such as the individual’s living situation, occupation, and personal relationships (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2016; Eriksson & Lindström, 2007; Helles et al., 2015). Effectively assessing these aspects of quality of life for individuals with any type of psychiatric disorder raises several methodological issues, notably (1) the problematic validity and reliability of adult self-report due to affective, cognitive, and reality distortion of symptoms; (2) intrinsic difficulties in assessing quality of life in people suffering from these disorders; and (3) low life expectations that may paradoxically lead individuals to rate their quality of life as high (Albrecht & Devlieger, 1999; Katschnig, 2000; Welham et al., 2001). In addition, responses may be biased by an individual’s current medications and motivation (or lack thereof) for life improvement (Jenkins, 1992). These factors—in addition to the inherently subjective nature of quality of life ratings—may result in large discrepancies between the target individual and an informant. As with other intrinsic or internalizing constructs, it is difficult to determine which report is “correct.” In comparing self-reported quality of life ratings to maternal and maternal proxy-report (i.e. how she thinks her adult child with ASD feels about his or her own quality of life) for adults with ASD; however, Hong and colleagues (2015) found that there were no significant mean differences between adult self-report and maternal proxy-report across the domains of physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. Overall, findings indicated that adults with ASD were able to reliably report on their own quality of life and that mothers are good reporters of their adult child’s subjective quality of life. Quality of life measures offer an opportunity to assess the extent to which adults with ASD are satisfied with the physical, psychological, and social aspects of their lives and have the potential to provide a fuller picture of an individual’s current functioning (Renty & Roeyers, 2006).

Service needs

Identification of unmet service needs is a key to enabling families and adults with ASD to seek out and acquire appropriate services. Few studies have examined the service needs and usage for adults with ASD, however. In a national study, Shattuck et al. (Shattuck et al., 2011) found 39% of young adults with ASD were no longer utilizing any services after exiting high school despite receiving special education services in the school system. Similarly, Nathenson and Zablotsky (2017) found that the percentage of young adults with ASD who received services significantly declined with age across all areas of service utilization following high school exit.

Even fewer studies have addressed service needs and usage in later adulthood. Turcotte et al. (2016) found that caregivers of adults with ASD reported significantly higher unmet needs for speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, social skills training, and one-to-one support than caregivers of children or adolescents despite the need for more services increasing with age. More recently, Dudley and colleagues (2019) investigated service use, unmet needs, and obstacles to service access for a large sample of adults with ASD. Results indicated adults with ASD living with family used fewer services, had more caregiver-reported unmet need, and faced more obstacles to accessing services than adults living in supported living facilities. Strikingly, 54% of caregivers reported that their son or daughter needed more services than they currently received. Still missing from the literature, however, is an understanding of how adults with ASD view their own service needs and the extent to which that aligns with other reporters.

Aims and hypotheses

Taken together, the outlined literature highlights necessity of research on the use of self-report measures for adults with ASD. Given the rapidly increasing number of adults with ASD, particularly those with average to above average IQs, addressing this gap is essential to advancing both research and clinical services in this population. The aim of this study was to examine the level of agreement between self- and caregiver-report of (1) symptom severity, (2) daily living skills, (3) quality of life, and (4) reported unmet service needs. Because level of agreement is not necessarily a measure of accuracy, we also assessed the extent to which the information provided by each reporter was predictive of objective employment and independent living outcomes.

Based on our clinical experiences and review of the existing literature, we hypothesized that caregiver-report and self-report would be significantly positively correlated on measures of symptom severity, daily living skills, and quality of life despite significant discrepancies across domains. We also hypothesized that caregiver-report would be most predictive of objective employment and living outcomes, above and beyond the predictive value of self-report responses across measures, and that caregiver-report may document higher unmet service needs than reported by adults with ASD.

Methods

Participants

Forty pairs of adults with ASD (80% male; age range: 23.83–47.84; M = 33.18 years) and their caregivers (29 mothers, nine fathers, and two other relative informants) participated in this study (see Table 1 for full sample characterization). Participants were identified as part of a longitudinal study examining caregiver-reported outcomes for adults with ASD who were diagnosed during childhood from 1969 through 2000. A total of 274 caregivers participated in this adult outcome survey. Participants for the longitudinal study were recruited from a clinical database of more than 3000 individuals who were seen at one of the University of North Carolina (UNC) TEACCH Autism Program clinics (TEACCH) between 1969 and 2000 using the following inclusion criteria: (1) at least 20 years of age at the time of the records review; (2) at least one clinical evaluation before the age of 17; (3) met criteria of a Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Schopler et al., 1988) score of 27 or higher; and (4) had a confirmed ASD diagnosis in archival clinical records. Please refer to Dudley et al. (2019) for further details about recruitment methods and demographics of the overall sample included in the larger longitudinal study. For 22 of the families enrolled in the longitudinal outcomes study, the respective adult with ASD also requested an opportunity to complete the survey in addition to having a caregiver participate.

Table 1.

Demographics for the total ASD sample (n = 40).

| Sex (% male) | 80% (n = 32) |

| Mean age (SD; range) | 33.18 (5.54; 23.83–47.84) |

| % Caucasian | 87.5% (n = 35) |

| Employment status (% employed) | 57.5% (n = 23) |

| Living situation | |

| Independently | 30% (n = 12) |

| Non-independently | 70% (n = 28) |

| Supported setting | 12.5% (n = 5) |

| With family | 57.5% (n = 23) |

| Caregiver (% mothers) | 72.5% (n = 29) |

ASD: autism spectrum disorder; SD: standard deviation.

To increase the number of pairs of caregivers and adults with ASD in this study examining self-report, recruitment letters were mailed to families who had not enrolled in the previous longitudinal study but who fit inclusion criteria of diagnosis of ASD during childhood and the additional inclusion criteria described above. Because the adults with ASD recruited were required to complete self-report measures with limited assistance, we only contacted individuals without a comorbid intellectual disability in their records and with a childhood IQ of 85 or higher. We mailed letters to 70 families. Of these 70 families, we were unable to contact 42 due to a variety of reasons such as current contact information being unavailable or initial phone calls to discuss interest in the study being unreturned. Of the 28 that were successfully contacted via phone, two families (7%) were determined to not meet final eligibility criteria because the adult with ASD would not be able to complete a survey independently. Of the 26 that were eligible, 24 enrolled (92% enrollment) and two (8%) declined to participate. Of the 24 pairs who were enrolled in the study, 18 completed both the caregiver and self-report surveys (75% completion). For these newly recruited pairs, an additional screening question at the end of the survey was included to determine the number of questions on which the adult received help answering. If an individual indicated that he or she received help on 10 or more questions, their data would have been excluded from the study. However, no participants who completed the survey indicated requiring this level of assistance.

To ensure that there were no significant differences between participants recruited through the longitudinal outcomes study and those recruited specifically for this study, we conducted t- and z-tests comparing the groups on key demographic characteristics. The two participant pools did not differ significantly on age (t(38) = 1.11, p = 0.27), proportion of male participants (z = −0.48, p = 0.63), proportion of adults with ASD living independently (z = −1.11, p = 0.27), or proportion adults with ASD who were employed (z = −0.42, p = 0.68). Across both recruitment efforts, a total sample of 40 caregiver–adult with ASD pairs participated in this study.

Measures

TEACCH Autism in Adulthood Survey

This 87-question survey was designed as a part of the larger longitudinal study and aimed to collect information about the current life characteristics of adults with ASD. Two versions of this survey were created, one for caregiver-report and one for self-report. This study utilized responses to survey questions regarding current living situation, employment status, and need for additional services for the adult with ASD.

For living situation, respondents were asked to select one option from a multiple-choice list describing the adult with ASD’s current housing. All adults in this sample lived independently, independently with a spouse or roommate, with parents or another relative/guardian, or in a non-familial supported setting (i.e. supervised housing or a community group home). Participants who lived on their own or with a spouse or roommate were classified as living “independently”; participants who lived with a parent or other guardian, in supervised housing, or in a community group home were classified as living “non-independently.” For employment, respondents were asked to select “yes” or “no” to a question asking if the adult with ASD currently had a paid job. For service need, respondents were asked to select “yes” or “no” to a question asking if they thought the adult with ASD needs any services besides the ones he or she was currently receiving.

Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition: Adult form (SRS-A)

Symptom severity was measured by the SRS-A (Constantino, 2012). The SRS-A is a 65-item measure that assesses the severity of social communication and restricted and repetitive behavior (RRB) symptoms in ASD across multiple domains. In addition to a total standard score, the SRS-A provides a social communication index (SCI) and RRB index to reflect the two categories of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-V) compatible symptoms. The caregiver completed the informant version of the SRS-A and the individual with ASD completed the self-report version of the SRS-A.

Both the informant and self-report versions have strong psychometric properties, with high internal consistency values across all forms (α = 0.94–0.96). The inter-rater reliability between self- and other-report on the SRS-A averaged r = 0.66 across a variety of informants (e.g. parents, spouses, etc.; Constantino et al., 2003). A more recent study assessing the validity of the SRS for use with an adult population found that SRS factors were highly correlated with ASD symptoms and behavioral measures and that SRS factors were differentially related to measures specific to social or behavioral domains (Chan et al., 2017).

T-scores of 59 and below on the SRS-A are classified as “within normal limits” and are generally not associated with clinically significant autism spectrum disorders. T-scores of 60 and above indicate clinically significant deficiencies in reciprocal social behavior across three ranges of impairment: t-scores of 60–65 fall in the “mild range”; t-scores of 66–75 fall in the “moderate range”; t-scores of 76 or higher fall in the “severe range,” and such scores are strongly associated with clinical diagnoses of ASD.

Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale (W-ADL)

The W-ADL was used as a measure of the daily living skills component of adaptive behavior (Maenner et al., 2013). The W-ADL measures the ability of individuals with intellectual/developmental disabilities in adolescence and adulthood to complete activities of daily living such as household chores and self-care routines. This measure lists 17 activities that are rated on a three-point scale (0 = “does not do at all,” 1 = “does with help,” and 2 = “independent”). It has been validated for use as a caregiver-report measure with individuals with Down Syndrome, Fragile X Syndrome, ASD, and intellectual disabilities. For caregivers, the W-ADL demonstrates high internal consistency (α = 0.88–0.92) and is reliable over time. In addition, the W-ADL was found to be highly correlated (r = 0.82) with the daily living skills subdomain of the Vineland Screener—a “gold standard” measure of adaptive daily living skills (Maenner et al., 2013). The W-ADL was selected for its brief and user-friendly format when being completed as part of a longer survey. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the W-ADL as a self-report measure.

Quality of Life Questionnaire (QoL-Q)

The QoL-Q is a 40-question measure that was developed to assess the quality of life of individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities (Schalock et al., 1993). It was designed for adults with intellectual disabilities and is intended for both self-report and caregiver or staff report. The QoL-Q contains questions across four subscales: life satisfaction, competence/productivity, empowerment/independence, and social belonging. Each subscale contains 10 questions, each with a one-point, two-point, and three-point response, wherein a higher score indicates a higher quality of life rating. Eight out of the 10 questions on the competence/productivity subscale can only be completed if the individual being rated is currently employed. The internal consistency of the subscales is relatively high (α = 0.66–0.83, total α = 0.83.). Though no studies have been conducted comparing self-report and informant-report on the QoL-Q in an intellectually high functioning sample or for individuals with ASD, specifically, research comparing staff and client ratings in other populations has found consistently low cross-informant correlations on all subscales (r = 0.07–0.31).

Procedure

This study is a part of a larger study conducted by the TEACCH Autism Program at UNC and has been approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board. After contact was made through recruitment efforts, potential participants were screened over the phone for eligibility. Once eligibility was established and the participants (both adult and caregiver) verbally indicated their desire to participate, they were enrolled. Measures were distributed either electronically or as a hard copy mailed to the participants, based on their individual preferences. The electronic version of the survey was presented via Qualtrics survey software and was distributed to participants by an email containing a unique link to the survey that is associated with the participant’s ID number. The paper and pencil version of the survey was distributed by mail, and each packet included a postage-paid envelope for returning the completed survey. If the surveys were not completed or returned within 2 weeks of receipt, a follow-up occurred via phone call. Participants who returned incomplete surveys or whose surveys contained unclear answers were also contacted by phone to ensure accurate and complete data collection. All caregivers completed the TEACCH Autism in Adulthood Survey, the W-ADL (Maenner et al., 2013), the SRS-A (Constantino, 2012), and the QoL-Q (Schalock et al., 1993) and adults with ASD completed the self-report versions of the same measures. The entire battery was estimated between 40 min and 1 h to complete, and each participant received $20.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0. Due to incomplete measures, data for two pairs on the SRS-A total score, three pairs on the QoL-Q total score, and two pairs on the W-ADL total score could not be included in final analyses.

Paired sample t-tests were conducted to examine discrepancies between self-report and caregiver-report on symptom severity using the SRS-A t-score, the daily living skills using the W-ADL total raw score, and the QoL-Q raw scores across three subdomains of satisfaction, belongingness, and empowerment; analyses excluded the competence subdomain, as it can only be completed if one is employed and not every participant was employed. A Z-test was conducted to examine the differences between caregiver and self-report in unmet service needs. Correlations were examined using Pearson’s r. Using Fisher’s r-to-z transformations (Fisher, 1921; Weaver & Wuensch, 2013), correlation coefficients were compared to the average inter-rater reliability of r = 0.45 observed in other populations on measures of symptom severity, as calculated through a meta-analytical approach across a sample size of 11,671 (Achenbach et al., 2005).

Separate hierarchical logistic regression analyses were performed for employment status and living situation to examine the extent to which symptom severity, daily living skills, and quality of life predicted employment status and living situation. For these analyses, employment status was classified as either currently employed or unemployed. Living situation was classified as either independent (i.e. living along or with a spouse/roommate without supports) or supported (i.e. living with a caregiver or in a supervised setting such as a group home).

Results

Prior to examining correlation and discrepancies between reporters, analyses were conducted to evaluate whether fundamental differences were based on level and frequency of contact between caregivers and adults with ASD and whether there were differences based on type of reported (i.e. maternal vs paternal or other family member). Living situation was considered a proxy measure for frequency of caregiver contact. Specifically, independent samples t-tests were conducted to test whether there were any differences in the size of the discrepancy between reporter scores on the included measures for adults living with the participating caregiver (n = 23) versus adults living away from the caregiver (n = 17). There were no significant differences between caregiver contact groups on the size of the discrepancy between caregiver and self-report scores on the SRS-A (t(36) = 0.72, p = 0.48), W-ADL (t(36) = −0.88, p = 0.39), or QoL-Q (t(35), p = 0.74). There was also no significant difference in age of the adult between groups (t(38) = 1.28, p = 0.21). Therefore, caregiver frequency of contact was not included in further analyses.

Similarly, there were no significant differences in the size of the discrepancy between reporters when comparing discrepancy size for maternal reporters (n = 29) versus other caregivers (i.e. fathers (n = 9) and other relatives (n = 2)) on the SRS-A (t(36) = 0.21, p = 0.84), W-ADL (t(36) = −1.17, p = 0.25), or QoL-Q (t(35) = 0.22, p = 0.83). Therefore, reporter type was not included in further analyses.

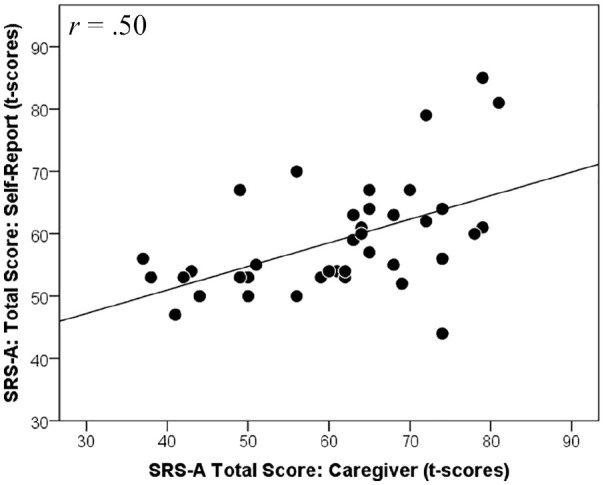

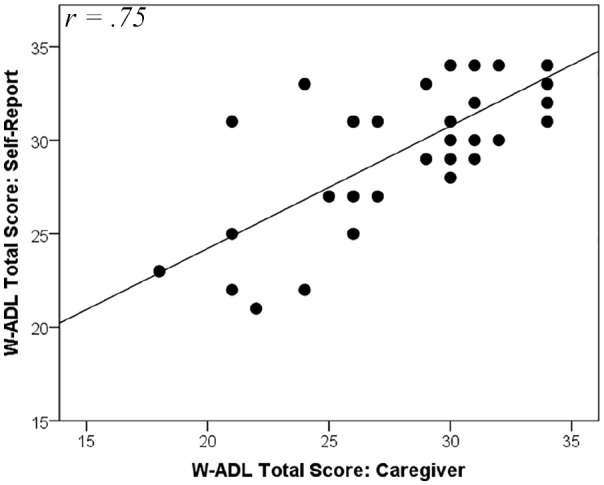

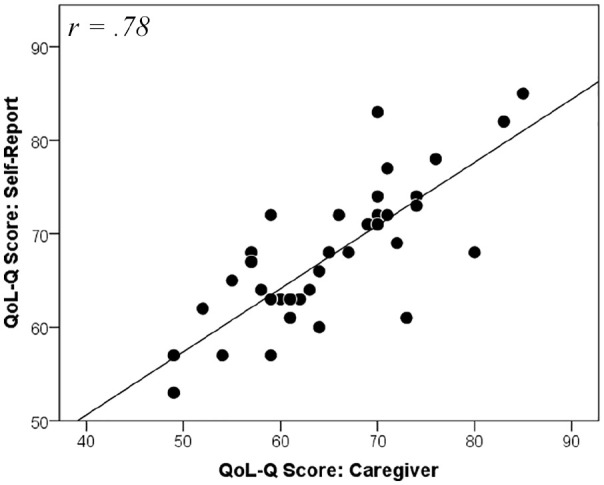

Correlation between caregiver-report and self-report

There was a significant positive correlation between caregiver- and self-report t-scores on the SRS-A total (r(36) = 0.50, p = 0.001; see Figure 1). The correlation on the SRS-A did not differ significantly from the expected average of r = 0.45 (Z = 0.39, p = 0.45). In addition, this correlation did not differ significantly from the median cross-informant agreement reported in the SRS-A manual, r = 0.66 (Constantino & Gruber, 2007; Z = -1.42, p = 0.07). There was also a significant positive correlation between caregiver- and self-report scores on the W-ADL (r(35) = 0.75, p < 0.001; see Figure 2), and the correlation was significantly higher than the expected average of r = 0.45 on measures of symptom severity (Z = 2.89, p = 0.004). For the QoL-Q total scores across the three included subdomains, there was a significant positive correlation between caregiver- and self-report total scores (r(36) = 0.78, p < 0.001; see Figure 3). This correlation was significantly higher than the expected average of r = 0.45 on measures of symptom severity (Z = 3.28, p = 0.001).

Figure 1.

Correlation between caregiver and self-report total scores (t-scores) on the SRS-A. Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity.

Figure 2.

Correlation between caregiver and self-report total scores on the W-ADL. Scores range from 0 to 34. Higher scores indicate a greater number of daily living skills used independently.

Figure 3.

Correlation between caregiver and self-report scores on the QoL-Q across three subdomains: satisfaction, belongingness, and empowerment. Higher scores indicate higher quality of life.

Discrepancies between caregiver-report and self-report

On the SRS-A, there was no significant difference between the caregiver-report t-score (M = 61.97, SD = 12.25) and the self-report t-score (M = 60.26, SD = 9.49; t(37) = −0.95, p = 0.35, d = 0.15). The SRS-A manual indicates that most informants’ scores will be less than 10 t-score points apart. Despite the non-significant difference and the small effect size of the difference between caregiver and self-report t-scores on the SRS, the t-scores for 14 pairs (35%) differed by 10 or more points.

On the W-ADL, there was a statistically significant difference with a moderate effect size between caregiver-report and self-report of the adult with ASD’s number of daily living skills (t(37) = 2.36, p = 0.02, d = 0.38). Caregivers reported that adults with ASD demonstrated significantly fewer (M = 28.87, SD = 4.39) daily living skills than adults with ASD self-reported (M = 30.00, SD = 3.81).

Analyses of total scores on the QoL-Q were conducted using scores across the three subdomains of satisfaction, belongingness, and empowerment; a 3 × 2 repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated an overall effect of reporter moderated by an interaction of scale type (F(2,72) = 3.40, p = 0.04). Follow-up paired t-tests revealed a significant difference with a moderate effect size between caregiver- and self-report scores on the satisfaction subdomain of the QoL-Q (t(39) = 2.96, p = 0.002, d = 0.55) with caregivers reporting significantly lower satisfaction ratings for the adults with ASD (M = 20.55, SD = 3.49) than adults with ASD reported for themselves (M = 22.43, SD = 4.07). There were no significant differences between reporters on the belongingness (t(36) = 1.14, p = 0.93, d = 0.02) or empowerment (t(39) = 1.28, p = 0.45, d = 0.12) subdomains. See Table 2 for all mean difference statistics.

Table 2.

Differences between self-report and caregiver-report on included measures.

| Adult: Mean (SD) | Caregiver: Mean (SD) | Test statistic (df) | Significance (two-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRS-A total (t-scores) | 60.26 (9.49) | 61.97 (12.25) | t(37) = –0.95 | p = 0.35 |

| SCI | 59.92 (9.01) | 60.97 (12.27) | t(37) = –1.17 | p = 0.25 |

| RRB | 63.20 (12.06) | 65.03 (12.78) | t(39) = –0.80 | p = 0.43 |

| QoL-Q total (three domains) | 67.57 (7.67) | 65.08 (8.87) | F(2, 72) = 3.40 | p = 0.04* |

| Satisfaction | 22.43 (3.49) | 20.55 (4.08) | t(39) = 2.96 | p = 0.002* |

| Belongingness | 19.89 (3.78) | 19.95 (4.37) | t(36) = 1.14 | p = 0.93 |

| Empowerment | 25.13 (3.60) | 24.78 (3.79) | t(39) = 1.28 | p = 0.45 |

| W-ADL total | 30.00 (3.81) | 28.87 (4.39) | t(37) = 2.36 | p = 0.02* |

SD: standard deviation; SRS-A: Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition: Adult form; SCI: social communication index; RRB: restricted and repetitive behaviors index; QoL-Q: Quality of Life Questionnaire; W-ADL: Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale.

Significant at the p < 0.05 level.

The TEACCH Autism in Adulthood Survey was used to assess reported unmet service needs. Specifically, the survey asked whether the reporter felt the adult needed any services besides those being currently received. A significantly higher proportion of caregivers (63%) than adults with ASD (35%) reported that the adult with ASD needed additional services that were not currently being accessed (Z = 2.5; p = 0.01).

Relationship to employment and independent living outcomes

We conducted two hierarchical logistic regressions with employment and living situation as dependent variables. At step 1, self-report SRS-A, W-ADL, and QoL-Q scores were entered; at step 2, caregiver SRS-A, W-ADL, and QoL-Q scores were entered.

For employment status, at step 1, the self-report measures significantly predicted employment status (Χ2 (3) = 16.12, p < 0.001). The model correctly classified 64% of unemployed and 86% currently employed adults based on their self-reported functioning. At step 2, caregiver-report measures significantly added predictive power to the model beyond self-report alone (Χ2 (3) = 9.00 p = 0.03) and the overall model significantly predicted employment status (X2 (6) = 25.12, p <.001). This combined self-report and caregiver-report model correctly classified 85.7% of unemployed and 90.9% employed adults. The Nagelkerke R2 = 0.68, indicating that 68% of the total variance in employment outcome was explained by the combined self-report and caregiver-report predictor variables. See Table 3 for hierarchical logistic regression parameter results.

Table 3.

Hierarchical logistic regression for employment.

| Step | X 2 | df | p-value | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Step 1 | 16.12 | 3 | 0.00* | |||

| SRS-A (self) | 0.87 | 0.75 | 1.00 | |||

| QoL-Q (self) | 1.11 | 0.96 | 1.29 | |||

| W-ADL (self) | 1.13 | 0.90 | 1.41 | |||

| Step 2 (step) | 9.00 | 3 | 0.03* | |||

| Step 2 (model) | 25.12 | 6 | <0.001* | |||

| SRS-A (self) | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.95 | |||

| QoL-Q (self) | 1.18 | 0.88 | 1.56 | |||

| W-ADL (self) | 0.59 | 0.31 | 1.13 | |||

| SRS-A (CG) | 1.08 | 0.95 | 1.24 | |||

| QoL-Q (CG) | 0.99 | 0.64 | 1.33 | |||

| W-ADL (CG) | 2.23 | 1.07 | 4.67 | |||

Significant at the p < 0.05 level. SRS-A: Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition: Adult form; QoL-Q: Quality of Life Questionnaire; W-ADL: Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale; CG: caregiver.

For living situation, at step 1, the overall model significantly predicted living situation (Χ2 (3) = 10.85, p = 0.01). This model correctly classified 50% of adults living independently and 87.5% of adults living with caregivers or in supervised housing. At step 2, the overall model significantly predicted employment status (Χ2 (6) = 15.56, p = 0.02) and the caregiver-report variables did not add significant contribution to the model (Χ2 (3) = 4.72, p = 0.19). This model correctly classified 66.7% of adults living independently and 87.5% of adults living with caregivers or in supervised housing. See Table 4 for hierarchical linear regression parameter results.

Table 4.

Hierarchical logistic regression for independent living.

| Step | X 2 | df | p-value | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Step 1 | 10.85 | 3 | 0.01* | |||

| SRS-A (self) | 1.10 | 0.96 | 1.26 | |||

| QoL-Q (self) | 1.11 | 0.81 | 1.04 | |||

| W-ADL (self) | 1.13 | 0.68 | 1.18 | |||

| Step 2 (step) | 4.72 | 3 | 0.19 | |||

| Step 2 (model) | 15.56 | 6 | 0.02* | |||

| SRS-A (self) | 1.06 | 0.92 | 1.22 | |||

| QoL-Q (self) | 0.81 | 0.64 | 1.03 | |||

| W-ADL (self) | 0.74 | 0.46 | 1.19 | |||

| SRS-A (CG) | 1.13 | 0.99 | 1.29 | |||

| QoL-Q (CG) | 1.13 | 0.91 | 1.40 | |||

| W-ADL (CG) | 1.29 | 0.80 | 2.07 | |||

Significant at the p < 0.05 level. SRS-A: Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition: Adult form; QoL-Q: Quality of Life Questionnaire; W-ADL: Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale; CG: caregiver.

Discussion

Overall, results indicated strong associations between caregiver and self-report responses on measures of symptom severity, daily living skills, and quality of life. However, some discrepancies between reporters was found with caregivers reporting more difficulties in everyday life skills, lower life satisfaction, and more unmet service needs than reported by adults with ASD. Furthermore, the combination of self-report and caregiver-report on all measures better predicted employment outcomes than did self-report alone. Taken together, these findings suggest that, while self-report and caregiver-report are both valid for this subset of adults with ASD, a multi-informant assessment may be the most comprehensive approach for evaluating current functioning and identifying service needs in this population.

In assessing symptom severity, our findings indicated that adults with ASD and their caregivers were consistent in their report of ASD symptoms. Caregiver and self-report responses demonstrated significant positive correlation with one another, on par with the median correlation reported in the original standardization study of the SRS-A (Constantino & Gruber, 2007), and there was no significant difference between reporters’ mean scores on the SRS-A. These findings indicate that adults with ASD of average to above average intellectual functioning can serve as reliable and accurate reporters of their own current symptoms of ASD. These findings contrast with previous research suggesting that poor social insight limits the validity of self-report for this particular population (e.g. Berthoz & Hill, 2005; Bishop & Seltzer, 2012).

Accurately assessing daily living skills is also a key part of shaping treatment planning and supporting increased independence for adults with ASD. In this study, we found that, despite a significant positive correlation between scores, there was a significant discrepancy between caregiver and self-report scores on the W-ADL. Specifically, caregivers reported that the adults with ASD demonstrated fewer daily living skills on average than adults reported about themselves.

Having accurate information on the W-ADL is essential in both clinical and research contexts, as adaptive behaviors and daily living skills have been consistently shown to be one of the best measures of long-term adult outcomes, including employment and quality of life (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2016; Farley et al., 2009; Klinger et al., 2015). In addition, research suggests that individuals with ASD who have average intelligence may have lower daily living skills than predicted by IQ (Howlin et al., 2004, 2014; Klinger et al., 2015). Thus, a measure of intellectual ability alone is not sufficient to identify daily service needs for adults with ASD. Given the role of daily living skills in promoting greater independence and more positive outcomes, they should be prioritized as a treatment target. In addition, reported deficits in independent daily living skills are often a core qualification for adult services through agencies such as vocational rehabilitation. Consequently, collecting a comprehensive report consulting multiple informants is more likely to result in appropriate referrals and services targeting everyday life skills.

Consistent with research in other populations (Ikeda et al., 2014; Shipman et al., 2011), caregivers reported significantly lower quality of life overall—particularly in the satisfaction domain—on the QoL-Q than adults with ASD reported about themselves, despite a significant positive correlation between reporters. Improving quality of life is a primary consideration in interventions and services for adults with ASD (Gerber et al., 2011); as such, an individual’s subjective feelings about one’s own life must be taken into account and, in many cases, may be given higher priority than an informant’s report. This research does not identify which reporter is more accurate in their assessment of quality of life. The assessment of objective adult life experiences may provide an important mechanism for assessing quality of life. For example, Hong and colleagues (2015) found that adults with frequent experiences of being bullied reported lower levels of subjective quality of life. Klinger and colleagues (2015) found that employment was significantly associated with higher quality of life in regards to subjective measures of satisfaction, sense of belonging, and empowerment. In this study, the addition of caregiver-report significantly predicted employment which may be a proxy for quality of life. Thus, this study suggests that gaining perspectives from both caregivers and adults with ASD may provide a more comprehensive picture of adult quality of life.

We also examined agreement between self- and caregiver-reported unmet service needs. In the larger caregiver survey associated with this study, Dudley et al. (2019) reported a high rate of unmet service needs across all categories of services (e.g. employment supports and daily living supports). When comparing caregiver and adult with ASD self-report, a significantly higher proportion of caregivers than adults with ASD reported that additional services were needed. Given the literature that many adults with ASD access fewer services following high school, despite a continued need for more support and intervention across a variety of domains (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2016; Dudley et al., 2019; Shattuck et al., 2012), the discrepancy between reporters is striking, further emphasizing the importance of accurately identifying the need for relevant services. Including both caregiver and self-report in assessment of unmet service needs can help to ensure that no potential treatment target is being overlooked, reducing barriers to access for an adult population.

Limitations and future directions

Although this study makes significant strides in improving our understanding of self-report for adults with ASD, there are still several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small. The hierarchical logistic regression analyses, in particular, may be underpowered given the number of included predictors. Future research examining a larger sample is recommended. In addition, the full sample was recruited from a pool of adults who were diagnosed as children. Individuals who received diagnoses as children are often different from those who did not receive diagnoses until later in life, as more substantial symptoms often result in earlier diagnoses. In addition, the use of survey data for individuals recruited from childhood records limited measures of current functioning. Specifically, current clinician assessments of ASD symptoms or intellectual functioning were not available. While childhood IQ can be considered a reliable predictor of cognitive functioning into adulthood (Howlin et al., 2014), we cannot report data on the current cognitive functioning of adults in our sample. Consequently, the characterization of our sample is limited, and our findings may not be representative of self-report capabilities across the spectrum of intellectually capable adults with ASD.

Analyses involving the W-ADL should also be interpreted with caution, as the measure contains only 17 items and the range of scores is 1 to 34. Given the limited range of possible scores, correlation between reporters was likely inflated when both members of adult–caregiver pairs scored at the ceiling for this measure. Additional research including a more comprehensive standardized measure of adaptive behavior/independent living skills, such as the Vineland (Cicchetti et al., 2013) or Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (Harrison & Oakland, 2015), is needed to confirm the findings in this study.

Future directions for this study also include expanding participant range of age and inclusion of other informants. A large proportion of adult assessments for ASD is conducted around the transition age (i.e. late teens to early twenties); the average age in our sample (33.18 years) was older than that time period, and the results presented here may be less applicable to transition-aged adolescents and young adults. In addition, given the age and cognitive functioning of the present sample, a caregiver may not always be the most appropriate secondary reporter. Future directions also include assessing the convergence between self-report and other informants such as friends, romantic partners, support staff, or roommates.

Furthermore, this study elected to focus on assessment domains specific to typical developmental disabilities-related assessments—in particular, the domains most relevant to documenting need for ASD-specific services and supports. However, we also recognize the need for mental health services in these populations, given high rates of depression and anxiety disorders (Buck et al., 2014). As assessing mental health difficulties in adults with ASD and establishing appropriately validated measures remains a challenge (Moss et al., 2015), future research should address convergence of reporters in this domain.

This research aims to help shape future measures so that clinicians and researchers can ascertain the most accurate picture of how an individual is functioning in the areas of symptom severity, daily living skills, and quality of life. Accurate assessment in these domains is important for assessment for adult developmental disability services. Our results suggest that there is significant convergence between adult self-report and caregiver-report. However, in areas in which we know reporters may differ (e.g. unmet service needs, daily living skills, and quality of life), a multi-informant assessment may provide the most accurate picture of everyday functioning. Alternatively, different cut-off scores for self-report than for informant-report may be needed in these areas. In a research context, having access to valid measures is also essential to move forward with treatment/intervention studies in this population, as such measures are essential for reliably capturing changes from pre- to post-intervention. This study may serve as a first step in demonstrating the importance of a multi-informant approach in assessing adults with ASD.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the individuals and families who contributed to this research. The authors would also like to thank Brianne Tomaszewski for her statistical consultation.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by a pilot study grant awarded to the first author by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (Grant no. UL1TR001111). Support was also provided by grants from Autism Speaks (Grant no. 8316) and the Foundation of Hope awarded to the last author.

ORCID iD: Rachel K Sandercock  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1086-1328

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1086-1328

References

- Achenbach T. M., Krukowski R. A., Dumenci L., Ivanova M. Y. (2005). Assessment of adult psychopathology: Meta-analyses and implications of cross-informant correlations. Psychological Bulletin, 131(3), 361–382. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.3.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht G. L., Devlieger P. J. (1999). The disability paradox: Highly qualified of life against all odds. Social Science and Medicine, 48, 977–988. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00411-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. P., Bush J. W., Berry C. C. (1986). Classifying function for health outcome and quality-of-life evaluation. Medical Care, 24(5), 454–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autism Speaks. (2013). National housing and residential supports survey: An executive summary. [Google Scholar]

- Baio J., Wiggins L., Christensen D., Maenner M., Daniels J., Warren Z., . . . Dowling N. F. (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(6), 1–23. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R. A., Knouse L. E., Murphy K. R. (2011). Correspondence and disparity in the self- and other ratings of current and childhood ADHD symptoms and impairment in adults with ADHD. Psychological Assessment, 23(2), 437–446. 10.1037/a0022172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaansen J. A., Meffert H., Hein S., Huizinga P., Ketelaars C., Pijnenborg M., . . . De Bildt A. (2011). Diagnosing autism spectrum disorders in adults: The use of Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) module 4. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(9), 1256–1266. 10.1007/s10803-010-1157-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz S., Hill E. L. (2005). The validity of using self-reports to assess emotion regulation abilities in adults with autism spectrum disorder. European Psychiatry, 20(3), 291–298. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S. L., Seltzer M. M. (2012). Self-reported autism symptoms in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(11), 2354–2363. 10.1007/s10803-012-1483-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick L., Hong J., Smith L. E., Makuch R. A., Greenberg J. S., Mailick M. R. (2016). Characterizing objective quality of life and normative outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorder: An exploratory latent class analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(8), 2707–2719. 10.1007/s10803-016-2816-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck T. R., Viskochil J., Farley M., Coon H., McMahon W. M., Morgan J., Bilder D. A. (2014). Psychiatric comorbidity and medication use in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3063–3071. 10.1007/s10803-014-2170-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher A. V. S., Cidav Z., Knapp M., Mandell D. S. (2014). Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(8), 721–728. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W., Smith L. E., Hong J., Greenberg J. S., Mailick M. R. (2017). Validating the Social Responsiveness Scale for adults with autism. Autism Research, 10, 1663–1671. 10.1002/aur.1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. V., Carter A. S., Gray S. A. O. (2013). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. In Volkmar F. R. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders (pp. 3281–3284). Springer; 10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3_255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino J. N. (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale (2nd ed.). Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino J. N., Davis S. A., Todd R. D., Schindler M. K., Gross M. M., Brophy S. L., . . . Reich W. (2003). Validation of a brief quantitative measure of autistic traits: Comparison of the social responsiveness scale with the autism diagnostic interview-revised. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(4), 427–433. 10.1023/A:1025014929212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino J. N., Gruber C. P. (2007). Social Responsiveness Scale. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley K. M., Klinger M. R., Meyer A., Powell P., Klinger L. G. (2019). Understanding service usage and needs for adults with ASD: The importance of living situation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 556–568. 10.1007/s10803-018-3729-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan A. W., Bishop S. L. (2013). Understanding the gap between cognitive abilities and daily living skills in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders with average intelligence. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 19, 64–72. 10.1177/1362361313510068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M., Lindström B. (2007). Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and its relation with quality of life: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 61(11), 938–944. 10.1136/jech.2006.056028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley M. A., McMahon W. M., Fombonne E., Jenson W. R., Miller J., Gardner M., . . . Coon H. (2009). Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average or near-average cognitive abilities. Autism Research, 2(2), 109–118. 10.1002/aur.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R. A. (1921). On the probable error of a coefficient of a correlation deduced from a small sample. Metron, 1, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber F., Bessero S., Robbiani B., Courvoisier D. S., Baud M. A., Traoré M. C., . . . Galli Carminati G. (2011). Comparing residential programmes for adults with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability: Outcomes of challenging behaviour and quality of life. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(9), 918–932. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P., Oakland T. (2015). Adaptive behavior assessment system (3rd ed.). Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Helles A., Gillberg C. I., Gillberg C., Billstedt E. (2015). Asperger syndrome in males over two decades: Stability and predictors of diagnosis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 56(6), 711–718. 10.1111/jcpp.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J., Bishop-Fitzpatrick L., Smith L. E., Greenberg J. S., Mailick M. R. (2015). Factors associated with subjective quality of life of adults with autism spectrum disorder: Self-report versus maternal reports. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(4), 1368–1378. 10.1007/s10803-015-2678-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P., Goode S., Hutton J., Rutter M. (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 45(2), 212–229. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P., Savage S., Moss P., Tempier A., Rutter M. (2014). Cognitive and language skills in adults with autism: A 40-year follow-up. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 55(1), 49–58. 10.1111/jcpp.12115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume K., Loftin R., Lantz J. (2009). Increasing independence in autism spectrum disorders: A review of three focused interventions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(9), 1329–1338. 10.1007/s10803-009-0751-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda E., Hinckson E., Krägeloh C. (2014). Assessment of quality of life in children and youth with autism spectrum disorder: A critical review. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 23(4), 1069–1085. 10.1007/s11136-013-0591-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C. D. (1992). Assessment of outcomes of health intervention. Social Science & Medicine, 35(4), 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. A., Filliter J. H., Murphy R. R. (2009). Discrepancies between self- and parent-perceptions of Autistic traits and empathy in high functioning children and adolescents on the Autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(12), 1706–1714. 10.1007/s10803-009-0809-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katschnig H. (2000). Schizophrenia and quality of life. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102, 33–37. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.00006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinger L. G., Klinger M. R., Mussey J. L., Thomas S. P., Powell P. S. (2015, May). Correlates of middle adult outcome: A follow-up study of children diagnosed with ASD from 1970-1999 [Conference session]. International Meeting for Autism Research, Salt Lake City, UT, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Kraper C. K., Kenworthy L., Popal H., Martin A., Wallace G. L. (2017). The gap between adaptive behavior and intelligence in autism persists into young adulthood and is linked to psychiatric co-morbidities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(10), 3007–3017. 10.1007/s10803-017-3213-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner M. J., Smith L. E., Hong J., Makuch R., Greenberg J. S., Mailick M. R. (2013). Evaluation of an activities of daily living scale for adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 6(1), 8–17. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell D. S., Knapp M. (2012, March). Estimating the economic costs of autism [Conference session]. Investing in Our Future: The Economic Costs of Autism Summit, ESF Centre, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky C. A., Kao J., Oswald D. P. (2011). Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 164–174. 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A. T., Powell P. S., Buttera N., Klinger M. R., Klinger L. G. (2018). Brief report: Developmental trajectories of adaptive behavior in children and adolescents with ASD diagnosed between 1968-2000. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 48(8), 2870–2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P., O’Keefe K. (2008). Brief report: Do individuals with autism spectrum disorder think they know their own minds? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(8), 1591–1597. 10.1007/s10803-007-0530-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss P., Howlin P., Savage S., Bolton P., Rutter M. (2015). Self and informant reports of mental health difficulties among adults with autism findings from a long-term follow-up study. Autism, 19(7), 832–841. 10.1177/1362361315585916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathenson R. A., Zablotsky B. (2017). The transition to the adult health care system among youths with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatric Services, 68(7), 735–738. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renty J. O., Roeyers H. (2006). Quality of life in high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder: The predictive value of disability and support characteristics. Autism, 10(5), 511–524. 10.1177/1362361306066604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalock R. L., Hoffman K., Keith K. D. (1993). Quality of Life Questionnaire. International Diagnostic Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Schopler E., Reichler R. J., Renner B. R. (1988). Childhood Autism Rating Scale. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Shalom B. D., Mostofsky S. H., Hazlett R. L., Goldberg M. C., Landa R. J., Faran Y., Hoehn-Saric R. (2006). Normal physiological emotions but differences in expression of conscious feelings in children with high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(3), 395–400. 10.1007/s10803-006-0077-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck P. T., Roux A. M., Hudson L. E., Taylor J. L., Maenner M. J., Trani J.-F. (2012). Services for adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry/Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 57(5), 284–291. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3538849&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck P. T., Wagner M., Narendorf S., Sterzing P., Hensley M. (2011). Post-high school service use among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 165(2), 141–146. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman D., Sheldrick R. C., Perrin E. C. (2011). Quality of life in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Reliability and validity of self-reports. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 32(2), 85–89. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318203e558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L. E., Maenner M. J., Seltzer M. M. (2012). Developmental trajectories in adolescents and adults with autism: The case of daily living skills. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(6), 622–631. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek A. A., Scholte E. M., Van Berckelaer-Onnes I. A. (2010). Theory of mind in adults with HFA and asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(3), 280–289. 10.1007/s10803-009-0860-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte P., Mathew M., Shea L. L., Brusilovskiy E., Nonnemacher S. L. (2016). service needs across the lifespan for individuals with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(7), 2480–2489. 10.1007/s10803-016-2787-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar F. R., Booth L. L., McPartland J. C., Wiesner L. A. (2014). Clinical evaluation in multidisciplinary settings. In Volkmar F. R., Paul R., Rogers S. J., Pelphrey K. A. (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (4th ed., pp. 661–672). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver B., Wuensch K. L. (2013). SPSS and SAS programs for comparing Pearson correlations and OLS regression coefficients. Behavior Research Methods, 45(3), 880–895. 10.3758/s13428-012-0289-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welham J., Haire M., Mercer D., Stedman T. (2001). A gap approach to exploring quality of life in mental health. Quality of Life Research, 10(5), 421–429. 10.1023/A:1012549622363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S. W., Schry A. R., Maddox B. B. (2012). Brief report: The assessment of anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 1138–1145. 10.1007/s10803-011-1353-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]