SUMMARY

Zika virus (ZIKV) causes microcephaly and disrupts neurogenesis. Dicer-mediated miRNA biogenesis is required for embryonic brain development and has been suggested to be disrupted upon ZIKV infection. Here we mapped the ZIKV-host interactome in neural stem cells (NSCs) and found that Dicer is specifically targeted by the capsid from ZIKV, but not other flaviviruses, to facilitate ZIKV infection. We identified a capsid mutant (H41R) that loses this interaction and does not suppress Dicer activity. Consistently, ZIKV-H41R is less virulent and does not inhibit neurogenesis in vitro or corticogenesis in utero. Epidemic ZIKV strains contain capsid mutations that increase Dicer binding affinity and enhance pathogenicity. ZIKV-infected NSCs show global dampening of miRNA production, including key miRNAs linked to neurogenesis, that is not observed after ZIKV-H41R infection. Together these finding show that capsid-dependent suppression of Dicer is a major determinant of ZIKV immune evasion and pathogenesis, and may underlie ZIKV-related microcephaly.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Zeng et al. assess the ZIKV-host interactome in NSCs and find the ZIKV capsid specifically binds and inhibits Dicer to limit host miRNA biogenesis, while other flaviviruses do not. Capsid-dependent Dicer suppression determines ZIKV immune evasion and pathogenesis, with implications for gain of pathogenic activity during ZIKV evolution.

INTRODUCTION

Zika virus (ZIKV) is causally associated with fetal microcephaly, intrauterine growth retardation, and other congenital malformations in humans (Brasil et al., 2016; Hoen et al., 2018; Johansson et al., 2016; Mlakar et al., 2016; de Oliveira et al., 2017; Rasmussen et al., 2016). ZIKV is reported to infect placenta and fetal brain during pregnancy (Calvet et al., 2016), particularly targeting neural stem and progenitor cells (NSCs) (Tang et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2016; Qian et al., 2016). However, it is still unclear why only ZIKV from flavivirus family is linked to microcephaly and other birth defects, which calls for a better understanding of its immune evasion and pathogenesis. Like other flaviviruses, the RNA genome of ZIKV encodes one polyprotein that is cleaved into three structure proteins and seven nonstructural proteins (Figure S1A) (Garcia-Blanco et al., 2016). However, host molecular targets of ZIKV proteins in NSCs remain largely unknown.

RNA interference (RNAi) is an important biological process in many eukaryotes during which small RNA molecules neutralized targeted mRNA molecules to inhibit the translation or gene expression (Wilson and Doudna, 2013). Dicer, a fundamental miRNA biogenesis enzyme, initiates the RNAi pathway by cleaving dsRNAs or stem-loop structure of precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) into short dsRNAs, and one strand of dsRNAs is directly loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Jinek and Doudna, 2009). The mature miRNA perfectly or partially pairs with complementary sites on target mRNAs, leading to the inhibition of mRNA stability or translation. miRNAs are involved in almost every cellular process and are essential for cell differentiation, development and homeostasis. Deregulation of miRNA is associated with numerous diseases in human. For example, Dicer deficiency leads to microcephaly in animal models (Davis et al., 2008); and several miRNAs, e.g. let-7a, miR-9, miR-17, and miR-19a, play crucial roles during fetal brain development (Rajman and Schratt, 2017). Moreover, dysregulation of host miRNA after ZIKV infection has been recently documented in NSCs (Dang et al., 2019), astrocyte-like SVG-A cells (Kozak et al., 2017) and mosquitoes (Saldaña et al., 2017). However, whether there is a direct link between Dicer-dependent miRNA system and ZIKV induced microcephaly is still unknown.

Although great progresses have been made toward infectious model establishment (Caine et al., 2018; Dong and Liang, 2018) and vaccine development (Diamond et al., 2019), two important questions regarding ZIKV are yet to be addressed: 1) what determines the unique pathogenesis of ZIKV on fetal brain development; 2) what mechanisms contribute to ZIKV evolution from a low-pathogenic virus to high-pathogenic virus? By establishing ZIKV-host interactome in NSCs, we identified Dicer as a restriction factor for ZIKV infection and a specific binding partner for ZIKV capsid. ZIKV capsid but not its H41R mutant antagonizes Dicer enzymatic activity and disrupts miRNA biogenesis, leading to impaired neurogenesis of NSCs in vitro and corticogenesis in vivo. Interestingly, the capsid from epidemic ZIKV strain has a higher binding affinity to Dicer than African strain capsid, thereby is more capable of inhibiting Dicer function and causing developmental impairment in embryonic brain.

RESULTS

ZIKV-host interactome identified Dicer as a restriction factor for ZIKV in NSCs

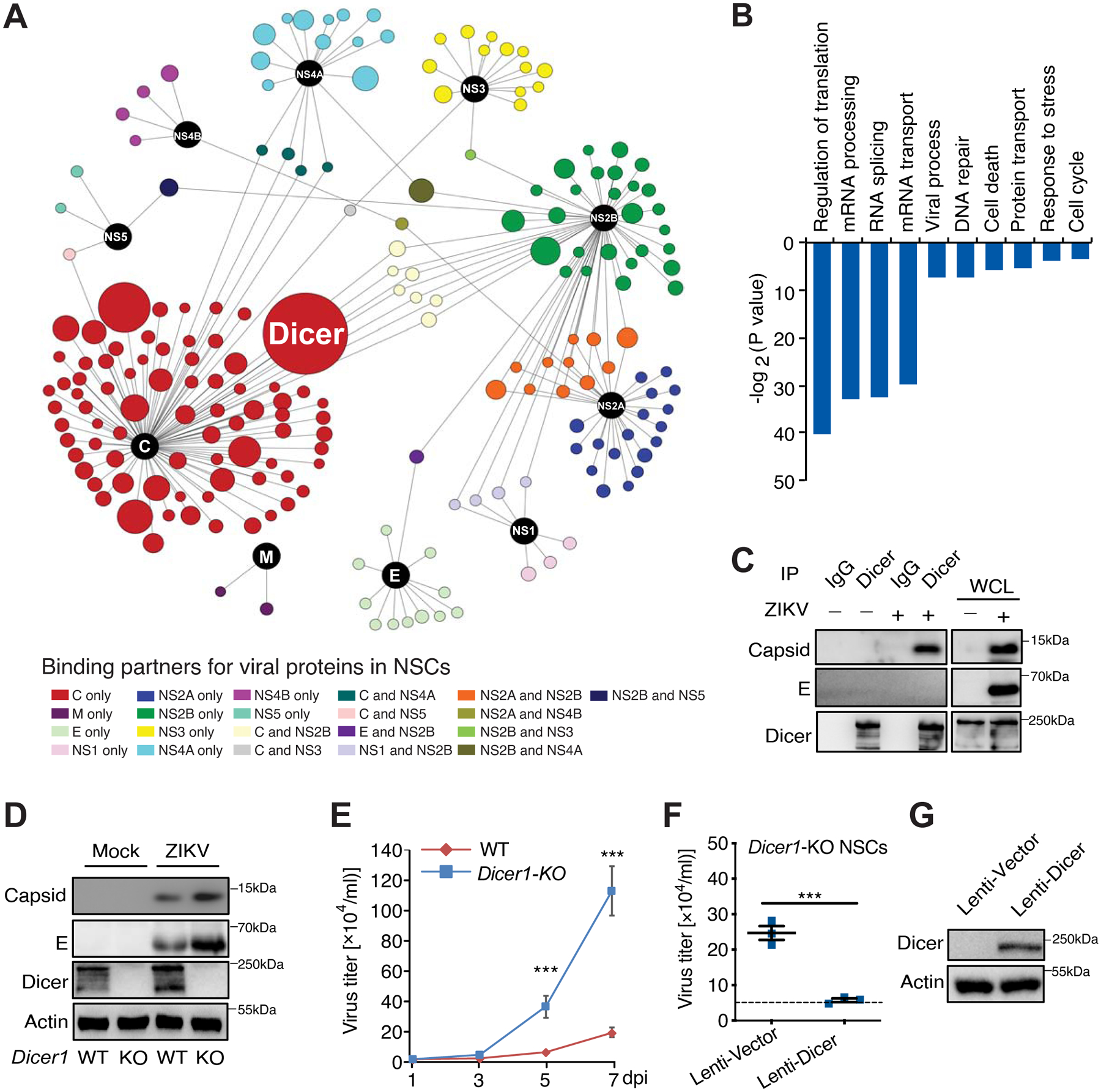

To fully understand the roles of these viral proteins during ZIKV life cycle, we first established the ZIKV-host interactome in human iPSC-derived NSCs. Briefly, we overexpressed each individual ZIKV protein carrying N-terminal 3xFlag-epitope in these cells, purified each ZIKV protein complex, and analyzed the co-purified cellular proteins by mass spectrometry in two independent biological repeats. With statistical analysis by SAINT algorithm (Choi et al., 2011), 235 unique interactions with 201 host targets were identified (Table S1) and used to generate interactome map by Cytoscape software (Figures 1A and S1B–K). It is worth noting that cell type specific ZIKV viral protein targets exist, as ZIKV-host interactomes in SK-N-BE2 (Scaturro et al., 2018) and HEK293T (Shah et al., 2018) cell lines share only ~7% overlap; similarly, our ZIKV-host interactome in NSCs only shares 18 or 13 common binding partners with these two reports, respectively (Figure S1L; Table S2). Host cellular pathways that are most likely affected by ZIKV are: translation, mRNA processing, RNA splicing, mRNA transport, and viral process pathways (Figure 1B). Several protein-protein interactions with greater interest were further validated by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) in HEK293T cells (Figure S2A).

Figure 1. ZIKV-host interactome network identified Dicer as a restrictor factor for ZIKV in NSCs.

(A) Overview of ZIKV-host interactome. Viral proteins (Baits) are shown as black color and candidate interacting proteins are shown as indicated colors. The node sizes are determined by peptide numbers from mass spectrometry analysis. (B) Major cellular pathways involved in candidate interacting proteins. (C) Endogenous Dicer binds to viral capsid at 48 h post ZIKV (SPH2015 strain) infection. (D–E) Wild-type (WT) or Dicer knockout (Dicer1-KO) mouse NSCs were infected with ZIKV SPH2015 strain (MOI: 0.01), and infected cells and culture supernatant were harvested at the indicated time point for detection of viral protein expression by immunoblotting (IB) (D), and virus titer by plaque assay (E). (F–G) Complementation of Dicer in Dicer1-KO mouse NSCs reduced ZIKV replication. NSCs were infected with lentivirus carrying vector or Dicer as indicated. After 48 h, lentivirus-transduced NSCs were infected with ZIKV SPH2015 (MOI: 0.01), and culture supernatant were harvested at 5 dpi for virus titer detection by plaque assay (F). Dash line indicates virus titer in WT mouse NSCs. IB indicates lentivirus-transduced Dicer expression in mouse Dicer1-KO cells (G). Mean ± SD; n = 3; ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test in E and F. See also Figures S1–S2 and Table S1–S3.

Within this ZIKV-host interactome, ribonuclease III-like enzyme Dicer is the top hit with 73 peptides (Table S3) covering more than 38% of Dicer amino acid sequence (Figure S2B). This interaction was confirmed at endogenous level in infected cells with co-IP using antibodies specific to human Dicer (Figure 1C). To examine the role of Dicer in ZIKV infection, we infected wild-type (WT) or Dicer knockout (Dicer1-KO) mouse NSCs with ZIKV Brazilian strain SPH2015 (Cunha et al., 2016). Dicer deficiency led to much higher ZIKV viral load in mouse NSCs, as shown by levels of viral proteins at 5 days post-infection (dpi) (Figure 1D), viral titers between 1 and 7 dpi (Figure 1E), and viral transcripts based on quantitative RT-PCR (Figure S2C). This was successfully rescued by re-expressing Dicer in Dicer1-KO mouse NSCs with a lentiviral construct (Figures 1F–G), indicating that the Dicer-dependent RNAi machinery restricts ZIKV.

ZIKV capsid specifically interacts with Dicer

As the capsids of flaviviruses share structural similarities (Figure 2A) (Li et al., 2018; Shang et al., 2018), we investigated whether this interaction is a common signature for flavivirus family. To our surprise, among all the capsids cloned, only ZIKV capsid bound strongly to Dicer (Figure 2B). As alignment comparison analysis demonstrated that ZIKV capsid has distinct amino acids compare to DENV type 2 (DENV2), West Nile virus (WNV) or Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), we generated ten ZIKV capsid mutants by replacing these ZIKV unique sequences with corresponding DENV2 or WNV sequences (Figure 2C), and found that a single mutation of histidine to arginine (H41R) completely abolished capsid-Dicer interaction (Figure 2D). More importantly, ZIKV capsid can directly bind to Dicer, as recombinant GST-tagged ZIKV capsid and human Dicer protein readily interacted with each other in vitro; while the GST-H41R capsid mutant lost its affinity to Dicer (Figure 2E). Detailed molecular mapping showed that the linker domain between these two RNase III domains of Dicer (aa 1403–1665) is responsible for ZIKV capsid interaction (Figures S1D and S1F). Structural modeling based on ZIKV capsid (PDB ID: 5YGH) (Li et al., 2018; Shang et al., 2018) and predicted Dicer linker domain (Liu et al., 2018) showed that H41 located on the interface between two proteins (Figure S1E), supporting the critical role of this unique residue.

Figure 2. ZIKV capsid specifically binds to Dicer and inhibits its enzymatic activity.

(A) Phylogenetic tree of the indicated flaviviruses based on their capsid sequence. Scale: 0.05. (B) ZIKV capsid but not capsids from other flaviviruses specifically binds to Dicer in HEK293T cells. (C) Alignment of capsids from indicated flaviviruses. (D) Mutation on histidine to arginine (Mut 3: H41R) abolishes the association between ZIKV capsid and Dicer in HEK293T cells. (E) 1 μg E. coli-purified GST, GST-ZIKV capsid (SPH2015) or H41R mutant was incubated with 0.2 μg recombinant Dicer at 4°C for 2 h. The mixture was subjected to GST-pull down and the co-precipitated proteins were analyzed by Coomassie blue (CB) staining or IB with indicated antibodies. The upper, middle, and bottom arrowheads represent Dicer, GST-capsid, or GST, respectively. (F) Schematic diagram of Dicer’s function in RNAi machinery. ZIKV capsid targets Dicer to block its activity. (G–H) ZIKV capsid blocks Dicer-mediated shRNA processing in cell (STAR Method: Reversal of silencing assay). Scale bar, 20μm. n = 4. (I) ZIKV capsid blocks Dicer-mediated pre-miRNA processing in cells in Let-7a reporter assay (STAR Method). n = 3. (J–K) ZIKV capsid but not its H41R mutant impairs Dicer activity in processing dsRNA in vitro. (J) E.coli-purified GST, GST-ZIKV capsid (SPH2015) or H41R mutant with indicated amount was incubated with 0.5 μg dsRNA (600 nt) and recombinant Dicer enzyme (1 unit) at 37°C for 2 h. In vitro Dicer cleavage dsRNA products were subject to bioanalyzer electrophoresis to quantify cleaved dsRNA fragments (fold change). n = 3. (K) 5 μg E.coli-purified GST, GST-ZIKV capsid (SPH2015) or H41R mutant was incubated with 0.5 μg dsRNA and Dicer (1 unit, 2 h) at 37°C. The reaction products were subject to agarose gel electrophoresis followed by EB staining. Mean ± SD; ns, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test in H, I, and J. See also Figures S2 and S3.

ZIKV capsid specifically inhibits Dicer’s function

Dicer cleaves dsRNA or shRNA into short dsRNAs (Jinek and Doudna, 2009). Since ZIKV capsid targets the linker domain between the two functional RNase III domains, ZIKV may modulate Dicer’s functions to facilitate virus replication and pathogenesis. To determine whether ZIKV capsid affects Dicer’s activity (Figure 2F), we first utilized a reversal-of-silencing assay to examine shRNA-mediated silencing (Paddison et al., 2002), by co-transfecting HEK293T cells with plasmids encoding GFP, GFP-specific shRNA (shGFP), and vector or flavivirus capsid plasmids (Figures 2G–H). ZIKV capsid, but not H41R mutant or vector control, efficiently attenuated Dicer-dependent shGFP processing and reduced the shGFP activity by nearly 3-fold (Figure 2H). In addition, capsids from other flaviviruses failed to block shGFP function (Figures 2G–H and S3A–B). On the other hand, in a siRNA-mediated knockdown assay that bypasses Dicer (Figure S3C), ZIKV capsid, its H41R mutant, or the capsids from other flaviviruses all failed to alter GFP-specific siRNA knockdown efficiency (Figures S3D–E), suggesting ZIKV capsid’s target is Dicer but not the downstream RISC. This finding was further confirmed by a transient let-7a reporter assay (Hutvágner et al., 2001), in which only ZIKV capsid inhibited Dicer-dependent let-7a production, instead of H41R mutant or the capsids from DENV2 or WNV (Figure 2I). More importantly, when tested in vitro to cleave long dsRNAs (~600 nt) into small dsRNA fragments (Figures S3F–G), Dicer’s ribonuclease activity was impaired in the presence of GST-capsid in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2J), which was not observed in the presence of GST-capsid H41R mutant or control GST (Figures 2J–K). As a direct comparison, in a similar in vitro cleavage assay using E. coli RNase III, neither GST-capsid nor GST-capsid H41R mutant affected its enzymatic activity on dsRNA cleavage (Figure S3H), indicating ZIKV capsid specifically targets host Dicer-dependent RNAi machinery.

Both capsid and Dicer are RNA-binding proteins, therefore capsid might inhibit Dicer through a competitive mechanism, which is least likely as capsid can directly bind to Dicer and other RNA-binding capsids from the flavivirus family had no obvious effect in our functional assays (Figures 2G–I). To further rule out such possibility, we performed RNase A treatment before co-IP and found that ZIKV capsid-Dicer association occurred in the absence of RNAs (Figure S3I). In addition, purified recombinant capsid-WT and capsid-H41R mutant had very similar binding affinities to dsRNAs in vitro (Figures S3J–K). Therefore, these results indicate that ZIKV capsid-mediated inhibition of Dicer is through direct interaction.

Generation and characterization of ZIKV-H41R mutant virus

To determine the role of Dicer modulatory activity of capsid during ZIKV infection, we introduced H41R mutation into a ZIKV infectious clone based on strain SPH2015 using reverse genetic (Zhao et al., 2018) and produced both ZIKV-WT and ZIKV-H41R mutant viruses from Vero cells (STAR Methods). In Vero cells, ZIKV-H41R replicated with less efficiency than ZIKV-WT based on viral loads (Figure 3A), although the differences were indistinguishable at early stages (Figures S4A–B). Importantly, ZIKV-H41R replicated as efficiently as ZIKV-WT in mouse Dicer1-KO NSCs (Figure 3B), suggesting that loss of inhibition on host Dicer as a direct consequence of this point mutation can substantially reduce ZIKV virulence. Immunostaining also showed that ZIKV capsid colocalized well with endogenous Dicer in human fetal NSCs (fNSCs) at 24 hours after infected with ZIKV-WT, which was dramatically reduced in case of ZIKV-H41R infection (Figures S4C–E). Consistently, ZIKV-WT led to 51% of cell death at 5 dpi (Liang et al., 2016), which was reduced nearly by half in fNSCs infected with ZIKV-H41R (Figures 3C–D). In addition, ectopic expression of capsidWT facilitated ZIKV infection in fNSCs and normalized the replicative difference between ZIKV-WT and ZIKV-H41R, which was not observed following capsidH41R expression (Figures 3E–F), further suggesting modulation of Dicer by capsid is key to ZIKV’s virulence in fNSCs.

Figure 3. Dicer determines the virulent difference between ZIKV-WT and ZIKV-H41R.

(A) The plaque morphology of ZIKV-WT and ZIKV-H41R. (B) WT or Dicer1-KO mouse NSCs were infected with ZIKV-WT or ZIKV-H41R (MOI: 0.01), and culture supernatant was harvested at 5 dpi for detection of viral titer by plaque assay. n = 3. (C-D) Representative images (C) and quantification of cell death (D) from Live/Dead cell viability assay in fNSCs at 5 dpi with ZIKV-WT, ZIKV-H41R, or mock treatment. Images were taken using live cell imaging. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 3. (E–F) CapsidWT but not capsidH41R facilitates ZIKV replication in fNSCs. fNSCs stably expressing vector, Flag-capsidWT, or Flag-capsidH41R were infected with ZIKV-WT or ZIKV-H41R (MOI: 0.01), and culture supernatant was harvested at 5 dpi for detection of viral titer by plaque assay (E). n = 4. The expression of viral envelope and Flag-capsid were detected by immunostaining (F). Scale bar, 30 μm. (G–I) In vivo abrogation of Dicer expression facilitates ZIKV replication and normalized the replicative difference between ZIKV-WT and ZIKV-H41R. (G) Schematic diagram of embryonic brain infection by ZIKV. Virus or Mock was micro-injected at lateral ventricle (LV) at E13.5 together with scramble or Dicer siRNA, and viral protein or RNA levels were examined at E18.5. (H) IB of E18.5 brain lysate with indicated antibodies. (I) ZIKV transcripts (red) were detected by in situ hybridization using ZIKV-specific RNAscope probes at E18.5. Scale bar, 50 μm. Mean ± SD; ns, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001 by Student’s t-test in B and E; **p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test in D. See also Figure S4.

Using an in utero injection protocol (Li et al., 2016a; Yuan et al., 2017) and combine with siRNA delivery in the cerebroventricular space/lateral ventricle at embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) (Figure 3G), we were able to determine the role of Dicer on ZIKV virulence in vivo. Different viral replication profiles between ZIKV-WT and ZIKV-H41R were also observed in mouse embryonic brains at E18.5 (Figures 3H–I). More specifically, ZIKV-H41R infection resulted in much lower levels of viral burden than ZIKV-WT in the presence of scramble siRNA, which were normalized after Dicer knockdown (Figure S4F), as shown by both immunoblotting (Figures 3H and S4G) and in situ hybridization using ZIKV-specific RNAscope probes (Figures 3I and S4H). These results indicate that capsid-mediated Dicer inhibition is also a determinant of ZIKV virulence in vivo, and ZIKV-H41R is still under the surveillance of host Dicer’s antiviral functions (Xu et al., 2019).

ZIKV Capsid is necessary for causing neurogenic deficits

Since both ZIKV infection (Li et al., 2016a; Yuan et al., 2017) and Dicer deficiency (Davis et al., 2008) can cause microcephaly in mice. Using the same in utero infection model (Figure 3G), we found that consistent with previously reports (Li et al., 2016a; Yuan et al., 2017), ZIKV-WT infected embryos exhibited smaller brain based on the measurements of brain width and cortical area at E18.5 (Figures 4A and S4I), when compared with embryos injected with Vehicle (Mock). This is in line with the elevated levels of apoptotic cell death in the cortical area (Figures S4J–K). However, ZIKV-H41R mutant virus had a very marginal effect on brain sizes (Figures 4A and S4I), which is correlated with reduced levels of viral burden (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. ZIKV capsid is necessary to drive neuropathogenesis by targeting Dicer.

(A–G) Embryonic brains were infected with ZIKV-WT (SPH2015), or ZIKV-H41R, or vehicle in the LV at E13.5 and inspected at E18.5. (A) Representative images showed the ZIKV-infected or Vehicle-infected brains (Mock) at E18.5 (upper panel). Scale bar, 2 mm. Red solid line and closed black dotted line represent brain width and cortical area, respectively (upper panel). Brain width from infected embryos was quantified (lower panel). n = 12. (B) Correlation of brain width with virus titer in ZIKV-infected E18.5 brain. (C) Representative images of CP at E18.5 immunostained with antibodies against cortical layer-specific markers CTIP2, SATB2, and TBR1 in ZIKV-infected embryonic brains. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D–G) Quantification of CP thickness (D), SATB2 positive cells upper layer neurons above CTIP2+ layer (E), CTIP2 positive deep layer neurons (F), and TBR1 positive subplate neurons (G) within the CP per mm2 from C. n = 6. (H–Q) Embryonic brains were infected with ZIKV-WT (SPH2015), or ZIKV-H41R, or vehicle in the LV at E13.5 and inspected at E16.5. Low magnification view of E16.5 hemisphere brain infected with ZIKV-WT virus (H, green). Dotted line indicates a border of CP or VZ/SVZ. Scale bar: 150 μm. (I–N) Representative images and quantification showing immunostaining of ZIKV and different neuronal linage markers including SOX2 (I–J) or PAX6 (K–L) in the VZ or SVZ, or DCX (M–N) in the CP. Scale bar: 30 μm. n = 4. (O) Representative images showing immunostaining of ZIKV and P-H3 in VZ/SVZ of ZIKV-WT- or ZIKV-H41R-infected E16.5 brains. Scale bar: 30 μm. (P–Q) Quantification of number of P-H3+ cells (P) and P-H3/ZIKV double positive cells (Q) per mm2 in the VZ from O. n = 6. Dotted line indicates a border of indicated layer in I, K and O. Mean ± SD; ns and ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test in A, D–G, J, L, N, and P–Q. See also Figure S4.

Furthermore, ZIKV-WT infection caused severe defects in corticogenesis as indicated by a substantial reduction (33.6%) in the thickness of cortical plate (CP) 5 days after in utero injection (Figures 4C–D and S4L). More importantly, immunohistological analyses demonstrated significant reductions in SATB2+ upper layer neurons (21.1%, Figure 4E), CTIP2+ deep layer neurons (32.0%, Figure 4F), and TBR1+ subplate neurons (39.2%, Figure 4G) (Leone et al., 2008), indicating impaired corticogenesis. More importantly, release of Dicer inhibition as the consequence of H41R mutation remarkably mitigated the corticogenesis defects in embryos infected with ZIKV-H41R (Figures 4C–G), suggesting that ZIKV-related microcephaly is, at least in part, through capsid and its inhibition of Dicer.

To determine how ZIKV impacts progenitors and differentiation in vivo, we further quantified the progenitors and newborn neurons at E16.5 after infection (Figure 4H). ZIKV-WT and ZIKV-H41R both effectively infected the SOX2+ and PAX6+ radial glial progenitors (Figures 4I–L), as well as TBR2+ intermediate progenitors and DCX+ newborn neurons (Figures 4M–N and S4M–N). However, at E16.5 we did not see dramatic changes in the density of SOX2+ and PAX6+ radial glial progenitors in the ventricular zone (VZ) (Figures 4I–L), or density of TBR2+ intermediate progenitors in subventricular zone (SVZ) (Figures S4M–N). Within 3 days of infection, ZIKV had not widely spread to CP yet (Figure 4H), and DCX+ newborn neurons in CP were not much affected either (Figures 4M–N). More importantly, we observed a substantial reduction of P-H3+ cells in VZ at E16.5 (Figures 4O–Q), indicating an inhibit of proliferation in neural progenitors. This effect is likely due to capsid-mediated Dicer dysfunction, as Dicer knockout embryos also exhibit loss of P-H3 in VZ (De Pietri Tonelli et al., 2008) and ZIKV-H41R infected VZ cells were still dividing (Figures 4P–Q). These results demonstrated that ZIKV is able to infect different linages of neural progenitor cells and inhibit progenitor proliferation, which contributes to ZIKV pathogenesis.

We next examined whether knockdown of Dicer further facilitates ZIKV virulence in vivo. Our data showed that siRNA mediated Dicer knockdown at E13.5 resulted significant impairment of corticogenesis, as shown by reduced cortical width and cortical area at E18.5 (Figures S4O–Q), as well as decreased thickness of both CP and VZ/SVZ layers (Figures S4R–T). More importantly, Dicer knockdown abolished the difference between the ZIKV-WT and ZIKV-H41R in compromising corticogenesis (Figures S4P–Q and S4S–T), which is consistent with our finding on ZIKV viral load in the presence of si.Dicer. Since Dicer knockdown and ZIKV-WT together did not result in an additive impact on corticogenesis, our results indicate that ZIKV capsid-mediated Dicer dysfunction is key to its pathogenesis in the fetal brain.

ZIKV Capsid protein is sufficient for causing neurogenic deficits

Next, we determined whether ZIKV capsid itself is sufficient to affect the proliferation and differentiation of human fNSCs in vitro. Unlike ZIKV NS4A and NS4B as we previously reported (Liang et al., 2016), expression of ZIKV capsidWT or capsidH41R (Figure S5A) did not change the size of neurospheres formed from fNSCs (Figures S5B–D), nor altered self-renewal of fNSCs as indicated by marker SOX2 (Figures S5E–F) (Fong et al., 2008). However, expression of capsidWT but not capsidH41R resulted in much fewer number of neurospheres formed in culture (Figures S5G–H), which is consistent with the deficits reported in Dicer1-KO mouse NSCs (Kawase-Koga et al., 2010). More importantly, fNSCs expressing capsidWT poorly differentiated into progenies (Figures S5I–K), as shown by 89.5% and 80.6% reductions in differentiation towards MAP2+ neuronal cells and GFAP+ astrocytes, respectively. Yet, capsidH41R expression had little effects on differentiations towards these lineages (Figures S5I–K), indicating that ZIKV capsid is sufficient to inhibit in vitro neurogenesis from fNSCs, which can be attributed to its interaction with Dicer.

To determine whether ZIKV capsid is sufficient to impair corticogenesis in vivo, we used Adeno-associated virus (AAV) to deliver ZIKV capsidWT, capsidH41R, or GFP control into E13.5 mouse embryonic cortices via in utero injection and analyzed the fetal brain development at later stages (Figure 5A). At E16.5, AAV broadly distributed in the whole brain (Figure 5A), and effectively infected both SOX2+ neural progenitor cells and DCX+ newborn neurons (Figures 5B–C and S5L–M). While neither AAV-CapsidWT nor AAV-CapsidH41R caused any changes in SOX2+ neural progenitor cells (Figures 5B–C) or DCX+ newborn neurons (Figures S5L–M), significantly fewer P-H3+ or Ki-67+ cells in the VZ were found in embryos infected with AAV-CapsidWT but not AAV-CapsidH41R when compared with AAV-GFP infected ones (Figures 5D–G), demonstrating that ZIKV capsid is sufficient to impair progenitor proliferation through Dicer inhibition, and mainly in a cell-autonomous manner.

Figure 5. ZIKV capsid is sufficient to drive neuropathogenesis by targeting Dicer.

(A) Schematic diagram of embryonic brain infection by AAV. Embryonic brains were infected at LV with AAV-GFP, AAV-CapsidWT, or AAV-CapsidH41R at E13.5 and inspected at E16.5. Low magnification view of E16.5 hemisphere brain infected with AAV-GFP. Dotted line indicates a border of CP or VZ/SVZ. Scale bar: 150 mm. (B–C) Immunostaining images of SOX2 in the VZ (B) and quantification of SOX+ AAV+ double positive cells (C) per mm2 in the VZ from B. Scale bar: 20 μm. n = 4. (D) Representative images of VZ immunostained with phospho-histone H3 (P-H3) and Flag (Flag-capsid) antibodies in AAV-infected E16.5 brains. Scale bar: 20 μm. (E) Quantification of number of P-H3+ AAV+ double positive cells per mm2 in the VZ from D. n = 6. (F) Representative images of VZ immunostained with Ki67 and Flag (Flag-capsid) antibodies in AAV-infected E16.5 brains. Scale bar: 20 μm. (G) Quantification of number of Ki67+ AAV+ double positive cells per mm2 in the VZ from F. n = 6. (H–K) Embryonic brains were infected at LV with AAV-GFP, AAV-CapsidWT, or AAV-CapsidH41R at E13.5 and inspected at E18.5. (H) Representative images of CP at E18.5 immunostained with antibodies against ZIKV capsid and cortical layer-specific markers CTIP2 and SATB2. Scale bar, 50 μm. (I–K) Quantification of CP thickness (I), SATB2 positive cells upper layer neurons above CTIP2+ layer (J), and CTIP2 positive deep layer neurons (K) within the CP per mm2 from H. n = 6. Mean ± SD; ns, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test in C, E, G, I–K. See also Figure S5.

At E18.5, AAV-GFP expression were more prominent in newborn neurons in the CP (Figure S5N). While the expression levels of AAV-capsidWT and AAV-capsidH41R were similar as verified by western blotting (Figure S5O) and immunohistological analysis (Figure 5H), expression of capsidWT but not capsidH41R caused severe defects in corticogenesis (Figures 5H–K), as indicated by a 27.9% reduction in the thickness of cortical plate (Figure 5I), as well as reductions in SATB2+ upper layer neurons (16.0%, Figure 5J), and CTIP2+ deep layer neurons (22.8%, Figure 5K). These data demonstrated that ZIKV capsid sufficiently modulated corticogenesis through Dicer in vivo, closely phenocopying ZIKV infection (Figure 4). Therefore, our results demonstrated that ZIKV capsid protein is necessary and sufficient for causing neurogenic deficits.

Capsid-Dicer association contributes to a high pathogenicity of the epidemic SPH2015 strain

Although initially isolated from Africa in 1947 (Dick et al., 1952), ZIKV had not been linked to microcephaly until the 2015–2016 worldwide outbreak in Brazil (Brasil et al., 2016; Hoen et al., 2018; Johansson et al., 2016; Mlakar et al., 2016; de Oliveira et al., 2017; Rasmussen et al., 2016). By comparing the capsid sequences (Cunha et al., 2016; Haddow et al., 2012), we found that there are two amino acids variation between the ancient African strain IbH30656 (ZIKV-IbH) and epidemic Brazilian strain SPH2015 (ZIKV-SPH) in the pre-α1 loop (Figure 6A). In fact, the capsidSPH had a higher binding affinity with Dicer than capsidIbH in the in vitro pulldown assay (Figure 6B), and inhibited Dicer functions to much lower levels than capsidIbH in let-7a miRNA reporter assay (Figure 6C), reversal-of-silencing assay using GFP-shRNA (Figures S6A–B), and in vitro cleavage assay (Figure 6D), indicating that the ZIKV epidemic strain may have reinforced its interaction with Dicer during evolution for its own advantage. Similar evolutionary changes such as single amino acid substitution in NS1 (A188V) or prM (S139N) have been reported to enhance ZIKV infectivity (Liu et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2017).

Figure 6. ZIKV epidemic strain causes elevated neuropathogenesis by strengthening capsid-mediated Dicer modulation.

(A) Alignment between capsids from indicated ZIKV strains. (B) CapsidSPH had a higher binding affinity with Dicer than CapsidIbH in vitro with similar procedure as 2E. (C–D) CapsidSPH causes stronger inhibition of Dicer than CapsidIbH in Let-7a reporter assay (C, STAR Method) and in processing dsRNA in vitro (D, similar procedure as 2J). The dash line indicates a baseline of dsRNA fragments without Dicer cleavage in D. n = 3. (E) Schematic diagram of strategy to generate chimeric ZIKV-SPHNPL recombinant virus. The chimeric ZIKV-SPHNPL was produced by replacing capsid 25SPF27 in SPH2015 infectious clone backbone with 25NPL27 from strain IbH30656. (F–H) Embryonic brains were infected with indicated viruses in the LV at E13.5 and inspected at E18.5. (F) Immunostaining of ZIKV envelope and DAPI in the brain sections. Scale bar, 50 μm. (G) Representative images showed the ZIKV-infected or Vehicle-infected brains (Mock) at E18.5. Scale bar, 2 mm. Red solid line and closed black dotted line represent brain width and cortical area, respectively. (H) Brain width from infected embryos was quantified from G. n = 10. (I) Correlation analysis of brain width in H with indicated virus titer at E18.5. The dash line indicates an average value of mock group. Mean ± SD; ns, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test in C, D, and H. See also Figure S6.

To test our hypothesis, we generated a chimeric ZIKV clone by substituting capsidSPF with capsidIbH in the ZIKV SPH2015 clone (Figure 6E) and produced the chimeric virus (ZIKV-SPHNPL) in Vero cells. Chimeric ZIKV-SPHNPL replicated less efficiently than ZIKV-SPH but better than ZIKV-IbH in fNSCs, which can be normalized by Dicer knockdown (Figure S6C). Next, we performed in utero infection of E13.5 embryos with ZIKV-SPHNPL, together with ZIKV-SPH and ZIKV-IbH, followed by analyses at E18.5. Similarly, the viral burden in ZIKV-SPHNPL infected brains was in between those with ZIKV-SPH and ZIKV-IbH, as shown by viral envelope protein staining or viral loads in the developing cortices (Figures 6F and S6D). ZIKV-SPHNPL infected brains had an average brain width or cortical area larger than the ones infected by ZIKV-SPH, but smaller than ZIKV-IbH infected ones (Figures 6G–H and S6E), which was also consistent with the levels of apoptotic cell death in these different groups (Figures S6F–G). Further analysis also indicated that the sizes of infected embryonic brains were tightly correlated with the levels of viral burden in the same tissue (Figure 6I), demonstrating that ZIKV’s pathogenic capacities in different strains may depend heavily on capsids and their abilities in antagonizing Dicer’s function.

Capsid-dependent inhibition of host miRNA biogenesis during ZIKV infection

To test whether ZIKV utilizes its capsid to inhibit Dicer and dampen host miRNA biogenesis, we infected fNSCs with ZIKV-WT or ZIKV-H41R, and isolated small RNAs from infected cells for miRNA sequencing (Figures 7A and S7A). 2 dpi was chosen as the viral burden was high enough for sequencing yet not confounded by the replication difference between ZIKV-WT and ZIKV-H41R (Figures 7B and S7B). Based on RNA-seq, ZIKV infections didn’t significantly alter the total read counts for rRNA-repeat elements (Figure S7C), tRNA (Figures S7D–F), or protein coding gene and LncRNA (Figures S7G–I), yet the miRNA profiles of ZIKV-WT infected fNSCs were very different from ZIKV-H41R infection and Mock conditions based on principle component analysis (Figure 7C), suggesting that host miRNA machinery is inhibited, but not the global RNA synthesis. More specifically, ZIKV-WT infection led to about 35% reduction of total miRNA reads compared to Mock condition (Figure 7D), resulting in 138 significantly downregulated miRNAs and only 2 upregulated ones (Figure 7E). Such phenotype was completely missing in ZIKV-H41R infected fNSCs (Figures 7D and 7F). The 138 downregulated miRNAs in ZIKV-WT infected fNSCs were enriched in functional pathways related to neurogenesis and neurodevelopment (Figure S7J; Table S4). For example, miR-1–3p, mir-17–3p, miR-26b-3p and miR-365b-3p target Hippo signaling pathway (Figures S7K–L); miR-19a-3p, mir-326, miR-497–5p and miR-935 target TGF-b signaling pathway (Figures S7K and S7M); let-7c-3p, let-7f-1–3p let-7f-2–3p and miR-195–5p target axon guidance pathway (Figures S7K and S7N); miR-30b-3p, mir-30c-2–3p, miR-365a-3p and miR-542–3p regulate stem cell pluripotency (Figures S7K and S7O). In addition, we further analyzed a few highly expressed miRNAs that are also essential for neurogenesis, such as let-7a, miR-9, miR-17 and miR-19a (Rajman and Schratt, 2017), and found that their levels were all attenuated in ZIKV-WT infected fNSCs but not in ZIKV-H41R infected ones (Figure 7G).

Figure 7. ZIKV infection suppresses host miRNA expression by targeting Dicer in NSCs.

(A) A diagram procedure of small RNA preparation for miRNA-seq in fNCSs infected with ZIKV-WT or ZIKV-H41R (MOI: 0.01). (B) RT-qPCR analysis of ZIKV Ns5 RNA in fNSCs infected with ZIKV-WT or ZIKV-H41R (MOI: 0.01) at indicated time points. (C) PCA analysis of each indicated group as computed by prcomp function in R and shown by scatterolit3d package. (D) ZIKV-WT but not ZIKV-H41R infection led to reduction on overall miRNA reads from miRNA-seq analysis. (E–F) Volcano plot of miRNA in ZIKV-WT- (E) or ZIKV-H41R- (F) infected fNSCs relative to mock control. All mapped reads were normalized to 1 million (RPM) and differentially expressed miRNAs were examined by t-test in R. Red dots: miRNAs with P-value less than 0.05; Blue dots: miRNAs with P-value no less than 0.05. (G) Relative expression heatmap of representative miRNAs in fNSCs infected by ZIKV-WT, or ZIKV-H41R relative to mock control in miRNA-seq. (H) Relative expression heatmap of representative pre-miRNAs and corresponding mature miRNAs in AAV-CapsidWT-, or AAV-CapsidH41R-infected E18.5 mouse embryo brains relative to AAV-GFP-infection group using TaqMan Advanced miRNA assays (STAR Methods). Mean ± SD; n = 3; ns and ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test in B and D. See also Figure S7 and Table S4.

Furthermore, we examined the levels of these miRNAs in E18.5 embryonic brain tissues using Taqman assays (Chen et al., 2005). Although the pre-miRNA levels of let-7a, miR-9, and miR-17/19a cluster were not much altered by AAV-capsidWT or AAV-capsidH41R (Figures 7H and S7P), their mature miRNA levels were much lower in AAV-capsidWT infected embryonic brains, but not in AAV-capsidH41R infected ones when compared with AAV-GFP group (Figures 7H and S7Q). More importantly, the Dicer-independent miR-451 (Cheloufi et al., 2010; Cifuentes et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010) exhibited no changes based on Taqman assays (Figures 7H and S7R), further confirming that ZIKV capsid specifically inhibit Dicer and miRNA biogenesis in vivo.

Finally, we determined whether the declined neurogenic miRNAs depend on the inhibition of Dicer upon ZIKV infection in vivo. We analyzed the miRNA levels in siRNA injected embryos at using Taqman assays. Dicer deficiency did not alter the pre-miRNA levels of let-7a, miR-9, and miR-17/19a in E18.5 embryonic brains with or without ZIKV infections (Figure S7S). However, their mature forms of miRNA were declined significantly in Dicer deficiency embryonic brains (Figure S7T), suggesting the important role of Dicer for the biogenesis of these miRNAs in vivo. More importantly, ZIKV-WT but not ZIKV-H41R infection inhibited the production of mature let-7a, miR-9, miR-17, and miR-19a in si.Scramble embryos, but these differences were normalized by si.Dicer, indicating ZIKV indeed regulates miRNA biogenesis through Dicer (Figure S7T).

Taken together, these data suggested that capsid requires Dicer to modulate miRNA biogenesis and impair brain development, and capsid-mediated Dicer inhibition is the primary inhibitory mechanism for host miRNA synthesis upon ZIKV infection.

DISCUSSION

Here, we reported a unique mechanism for ZIKV immune evasion and pathogenesis in developing brain. With an evolutionally enforced ability, ZIKV capsid hijacks Dicer to facilitate viral evasion from host RNAi machinery and consequently blocks neurogenesis and cortical development. Interestingly, this mechanism is very specific to ZIKV, since the capsids from other flaviviruses do not interact with human Dicer nor block its activity. The association between ZIKV capsid and human Dicer relies on the presence of histidine on position 41 (H41) of ZIKV capsid, whereas the corresponding amino acid is arginine or lysine for other flavivirus capsids, suggesting the side chain charge change might be responsible for this unique interaction. The Dicer-binding deficient H41R mutant capsid cannot efficiently inhibit Dicer’s activity as ZIKV capsid-WT in vitro, although they exhibited similar binding affinity to dsRNA in vitro, suggesting the direct interaction between ZIKV capsid and Dicer plays more dominant role for the inhibition. Previous studies have reported several viral siRNA repressors (VSRs) from different viruses, including 3A protein of human enterovirus 71 (Qiu et al., 2017), NS1 of influenza A virus (Li et al., 2016b), and capsid of YFV (Samuel et al., 2016). These VSRs are RNA-binding proteins and inhibit host RNAi by competing substrate dsRNA association with Dicer. The flavivirus capsids are RNA-binding proteins for guiding the viral RNA genome into the capsid shell during assembly. However, ZIKV capsid interacts with Dicer in an RNA-independent manner, since the interaction affinity stays unchanged in the presence of RNase A treatment. These two abilities of ZIKV capsid, RNA-binding and Dicer-binding, gift ZIKV a potent blockage of host RNAi pathway, as we observed a global dampening of host miRNA biogenesis in infected NSCs.

ZIKV capsid is a relative conserved protein during evolution and consists of four α helices interspersed by loops in structure (Li et al., 2018; Shang et al., 2018). There are only two amino acid variations between epidemic strain and African strain, which is responsible for the higher binding affinity between epidemic ZIKV capsid and Dicer. These two different amino acids locate on the pre-α1 loop, and the critical Dicer interaction site H41 locates right after helix α1. The pre-α1 loop and α1 helix form the top layer of the structure, which is apart from the RNA-binding helix α4 on the bottom layer, providing the interaction interface for human Dicer. By comparison with the available capsid structures of WNV (Dokland et al., 2004) and DENV (Ma et al., 2004), the helices α2 and α4 of ZIKV capsid share a similar structural fold, which are responsible for the common viral RNA genome binding and assembly; the N-terminal pre-α1 loop and α1 helix are divergent, leading to much larger dimer interface in ZIKV capsid (4658 Å2) than that of WNV capsid (3395 Å2) or DENV capsid (3037 Å2), which potentially creates enough interface for human Dicer association (Li et al., 2018; Shang et al., 2018).

Collectively, our results demonstrated a unique molecular mechanism by which ZIKV successfully hijacks a host surveillance program dependent on the RNAi machinery, which are largely consistent with previous finding showing ZIKV infection altered host miRNA profiles in NSCs (Dang et al., 2019), astrocytes cell line SVG-A (Kozak et al., 2017), and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (Saldaña et al., 2017). Mechanistically, ZIKV capsid can directly interact with Dicer and inhibit its ribonuclease activity, dampening the production of host miRNAs that are essential for neurogenesis and cortical development. More importantly, the host-pathogen evolutionary arms race may have reinforced this interaction and contributed to ZIKV’s evolution from a low-pathogenic virus to a global congenital pathogen. Such information may guide the development of small molecules to antagonize ZIKV capsid functions. Taken together, our studies reported a unique molecular mechanism by which ZIKV antagonizes host Dicer-mediated RNAi in NSCs and provides insights into a therapeutic target for anti-ZIKV drug development.

LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

This report demonstrated the unique role of ZIKV capsid on Dicer-mediated miRNA biogenesis, which is critical for neurogenesis of NSCs. Due to the space limit, the ZIKV capsid-mediated inhibition on viRNA generation will be separately addressed in future. One limitation is that the microinjection model used in this study only discussed the inhibitory mechanism on neurogenesis after ZIKV enters fetus brain, but not the mechanism about how ZIKV passes through the mother-fetus barrier.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Lead Contact Qiming Liang (liangqiming@shsmu.edu.cn).

Materials Availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

The datasets generated during this study were deposited to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository with the accession number GSE137592.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines

HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco-BRL) containing 4 mM glutamine and 10% FBS. Vero cells were cultured in DMEM with 5% FBS and 4 mM glutamine. Transient transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #11668019). Human fetal NSCs were maintained as neurospheres in DMEM/F12 supplemented with StemPro Neural Supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #1050801) using suspension culture dishes (Corning, Acton, MA). All viral infections, including ZIKV and lentiviruses, were performed on low passage fNSCs from two primary isolates (Liang et al., 2016). NSCs stably expressing ZIKV viral proteins were generated using a standard selection protocol with puromycin (2 μg/ml). For assays requiring adherent culture, NSCs were plated on poly-L-Orthithine (10 μg/ml) coated plates or cover glasses.

Dicer1-KO mouse NSCs were obtained from E12.5 Dicer1lox/lox; Nes-Cre embryos, as previously published (Andersson et al., 2010). Briefly, we bred Dicer1lox/lox (JAX stock #006001) and Nes-Cre (JAX stock #003771) to get Dicer1lox/+; Nes-Cre mice, which were crossed with Dicer1lox/lox females to generate Dicer1lox/lox; Nes-Cre embryos. E12.5 embryos were genotyped first for the Cre and Dicer alleles by PCR. Cortices from Dicer1lox/lox; Nes-Cre embryos were pooled, dissociated into single cells, cultured and maintained as neurospheres using StemPro Neural Supplement in the presence of 10 μg/ml recombinant EGF and 10 μg/ml recombinant FGF2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), as we previously reported (Guo et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016). Dicer1-KO NSCs have reduced capacity of forming neurospheres, therefore we used secondary culture of Dicer1-KO NSCs for subsequent infection experiments. NSCs from Dicer1lox/lox embryos were used as control (WT). All mouse NSCs were tested positive for Nestin and Sox2. Three independent isolates of Dicer1-KO NSCs from different litter of embryos were used.

Human iPSC lines derived from health donor’s fibroblasts were obtained from Coriell cell repositories. The clone ID are: CW60201 (Female 30 YR), CW60279 (Female 32 YR) and CW60441 (male 30 YR). All cells were certified by Coriell to be: 1) No more than 1 SNP difference between clone and donor; 2) Classified based on gene expression profilings as iPSC; 3) Evidence not containing converting Plasmids; 4) with normal karyotype, 5) free for Mycoplasma contamination and Negative for Bacteria and Fungus. iPSCs were maintained in mTeSR medium (Stemcell Technology, #85850). Direct differentiation of iPSCs to neuron stem cells (NSCs) via embryoid body and rosette formation, followed by rosette selection and replating using Neural Induction Medium (Stemcell Technology, #05835), following manufacturer’s instructions. iPSC-derived NSCs were maintained in early passage (<4 passages) using STEMdiff™ Neural Progenitor Medium (Stemcell Technology, #05833). NSCs derived from CW60201 or CW60279 were used as two independent experiments for purification of ZIKV vial protein complexes and mass spectrometry.

Animals

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University of School of Medicine and University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine. Timed-pregnant C57BL/6J female mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories with the plug day designated as embryonic day 0 (E0). The operators responsible for experimental procedure and data analysis were blinded and unaware of group allocation throughout the experiments.

METHODS DETAILS

Plasmids

ZIKV cDNA and the capsids of DENV2, WNV, YFV, JEV, HCV, OHFV, and TBEV were synthesized as DNA fragments (Sangon Biotech) and these expression constructs were amplified by PCR and cloned into pEF-3xFlag, pGEX-6p-1, or pCDH-Flag vectors. Mutations of ZIKV capsid were generated using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). RNF34, FAM207A, DDX39B, JAK1, UBA1, SAE1, MOV10, DDX1, ZCCHC8, and PKR were amplified from cDNA library and cloned into pEF vector. The constructs of Dicer, IKBKAP, Atg9A, and STAT1, were kindly provided by Drs. Bishi Fu and Shitao Li. All constructs were sequenced using an ABI PRISM 377 automatic DNA sequencer to verify 100% correspondence with the original sequence. pLKO.1-GFP-shRNA was a gift from David Sabatini (Addgene, #30323). pRL-TK-let-7a was a gift from Phil Sharp (Addgene, #11324). pCMV-3Flag-luciferase was described previously (Liang et al., 2011).

Viruses

Zika virus.

ZIKV strain SPH2015 was a gift from Dr. Gang Long (Institut Pasteur of Shanghai, Chinese Academy of Sciences) (Zhao et al., 2018). ZIKV strain IbH30656 was purchased from ATCC (#VR-1839). Virus stocks were propagated in Vero cells after inoculating at a MOI of 0.02 and harvesting supernatants at 4 days post-infection (dpi). The titers of ZIKV stocks were determined by standard plaque assay on Vero cells.

Generation of recombinant ZIKV mutant virus.

The H41R single-amino acid substitution or 25SPF27 to 25NPL27 two-amino acid substitutions in capsid was introduced into the infectious clone of ZIKV SPH2015 (KU321639), a genetic reverse system as described previously (Zhao et al., 2018). The infectious clone plasmid was linearized by Mlu1 digestion and purified by Phenol/Chloroform extraction. In vitro transcribed viral RNA was prepared with T7 transcription kit and purified following the protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #AM1344). The purified viral RNA was electroporated into Vero cells and the culture supernatants were collected at 72 h post-electroporation. The infectious virions were detected by plaque assay and viral antigen expressions were detected by immunoblotting. RT-PCR and DNA sequencing were used to confirm the substitution site.

Lentivirus production.

Lentiviruses were generated by co-transfection of pCDH-Flag-capsidWT or pCDH-Flag-capsidH41R with three packaging plasmids into HEK293T cells. The culture supernatant was collected at 72 h post-transfection and purified by Lenti-X Concentrator (Clontech, #631231) and then titered with standard colony formation assay.

Adenovirus-associated virus (AAV) production.

GFP, Flag-capsidWT, or Flag-capsidH41R were cloned into AAV vector (Addgene, #37825), and then transfected into HEK293T cells with AAV-PHP.B plasmid (gifted from Dr. Viviana Gradinaru lab) for 3 days to produce AAVs. AAVs-containing supernatants were collected and purified by AAV Purification Mega Kit (Cell Biolabs, #VPK-141). The concentration of purified AAVs was determined by AAV Quantification Kit (Cell Biolabs, #VPK-145) and finally AAVs of 50 μl volume at the concentration of 5×1011 vg/mL was obtained.

Mass spectrometry, Sequencing, and Bioinformatic Analysis

Mass spectrometry

Excised gel bands were cut into approximately 1 mm3 pieces. Gel pieces were then subjected to a modified in-gel trypsin digestion procedure. Gel pieces were washed and dehydrated with acetonitrile for 10 min. followed by removal of acetonitrile. Pieces were then completely dried in a speed-vac. Gel pieces were rehydrated with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution containing 12.5 ng/μl modified sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) at 4°C. After 45 min, the excess trypsin solution was removed and replaced with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution to just cover the gel pieces. Peptides were later extracted by removing the ammonium bicarbonate solution, followed by one wash with a solution containing 50% acetonitrile and 1% formic acid. The extracts were then dried in a speed-vac (~1 hr) and stored at 4°C until analysis.

On the day of analysis, the samples were reconstituted in 5–10 μl of HPLC solvent A (2.5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid). A nano-scale reverse-phase HPLC capillary column was created by packing 5 μm C18 spherical silica beads into a fused silica capillary (100 μm inner diameter × ~12 cm length) with a flame-drawn tip. After equilibrating the column each sample was loaded via a Famos auto sampler (LC Packings, San Francisco CA) onto the column. A gradient was formed and peptides were eluted with increasing concentrations of solvent B (97.5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid).

As peptides eluted, they were subjected to electrospray ionization and then entered into an LTQ Velos ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were detected, isolated, and fragmented to produce a tandem mass spectrum of specific fragment ions for each peptide. Dynamic exclusion was enabled such that ions were excluded from reanalysis for 30 s. Peptide sequences (and hence protein identity) were determined by matching protein databases with the acquired fragmentation pattern by the software program, Sequest (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The human IPI database (Ver. 3.6) was used for searching. Precursor mass tolerance was set to +/− 2.0 Da and MS/MS tolerance was set to 1.0 Da. A reversed-sequence database was used to set the false discovery rate at 1%. Filtering was performed using the Sequest primary score, Xcorr and delta-Corr. Spectral matches were further manually examined and multiple identified peptides (>=2) per protein were required.

SAINT analysis of AP-MS data

Two biological repeats were performed for each ZIKV protein complex. The resulting data are presented in Tables S1 and S3. Proteins found in the control group were considered as non-specific binding proteins. The SAINT algorithm (http://sourceforge.net/projects/saint-apms) was used to evaluate the MS data. The SAINT utilizes label-free quantitative information to compute confidence scores (probability) for putative interactions. Such quantitative information can include counts (e.g. spectral counts or number of unique peptides). In an optimal setting, SAINT utilizes negative control immunoprecipitation data (typically, purifications without expression of the bait protein or with expression of an unrelated protein) to identify non-specific interactions in a semi-supervised manner. A separate unsupervised SAINT modeling is capable of scoring interactions in the absence of implicit control data, but only when a sufficient number of experiments are used for the modeling. The default SAINT options were low Mode = 1, min Fold = 0, and norm = 0. The SAINT scores computed for each biological replicate were averaged (AvgP) and reported as the final SAINT score. The fold change was calculated for each prey protein as the ratio of spectral counts from replicate bait purifications to the spectral counts of the same prey protein across all negative controls. A background factor of 0.1 was added to the average spectral counts of negative controls to prevent division by zero. The proteins included in the final interactome list had an AvgP ≥ 0.89. The threshold for SAINT scores was selected based on receiver operating curve analysis performed using publicly available protein interaction data. A SAINT score of AvgP ≥0.89 was considered a true positive BioID protein with an estimated FDR of ≤2%. Proteins with SAINT score <0.89 are considered as non-specific binding proteins.

Bioinformatic analysis

The ZIKV-Host protein interaction network was generated in Cytoscape (www.cytoscape.org). The binding partners of ZIKV viral proteins were analyzed in STRING (http://string-db.org) with the confidence score of 0.4. Gene Ontology analysis was performed using DAVID 6.8 Beta (http://david-d.ncifcrf.org).

miRNA Library Construction

1×106 NSCs were infected with ZIKV-WT or ZIKV-H41R at MOI: 1 and total RNA was extracted with at 2 dpi. miRNA was isolated for construction of miRNA sequencing library with QIAseq miRNA Library Kit (Qiagen, #331505) by UCLA Technology Center for Genomics & Bioinformatics (TCGB), followed by deep sequenced using Illumina HiSeq3000. Briefly, the workflow consists of 3’ ligation, primer hybridization, 5’ ligation, first strand synthesis and PCR amplification. Different adapters were used for multiplexing samples in one lane. AMPure XP Beads were used for dual size selection. Library quality was checked with Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and Qubit (Life Technologies).

miRNA sequencing analysis

Primary sequences data were checked by FastQC version 0.11.7 for quality control purpose. To increase accuracy, reads have N base were removed by cutadapt version 1.16 (--max-n 0) (Martin, 2011). Trimmed reads were mapped to human genome GRCh38 using Bowtie version 1.2.2 with option -n 0 -l 17 -a -- best --strata to find the best aligned reads (Langmead et al., 2009). Seed length for alignment was set as 17 and no mismatch was allowed in seed region. PCA analysis of each group was performed as computed by prcomp function in R and shown by scatterolit3d package. Reads counts for genes were summarized by featureCounts v1.6.4 based on a merged annotation files containing miRNA information from miRbase 22 and sequence for other genes (non-coding RNA, tRNA, repeat elements, protein coding genes etc) from UCSC. The read counts for each gene were normalized by total aligned reads for each sample. All mapped reads were normalized to 1 million (RPM), and differentially expressed genes were picked by two-way t-test based on normalized read counts as presented by volcano plot. miRNA pathways of the top 50 miRNAs with reduced expression were analyzed in DIANA-mirPath tool (mirPath v.3 version, http://snf-515788.vm.okeanos.grnet.gr) with KEGG database, where representative miRNAs and their host targets were also plotted, as shown in Figure S7.

ZIKV capsid-Dicer co-structure prediction

Dicer Linker domain (amino acid 1403–1665) structure was generated by i-TASSER (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/). ZIKV capsid were separated from PDB ID: 5YGH, and saved in PDB format using PyMOL Viewer, and submitted to HDOCK server (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/). HDOCK server was a template-based modeling platform, and used to predict and evaluate the complex structure of protein-protein interactions. The prediction model with best score ranking was used for generating the co-structure figures with PyMOL software (pymol.org).

Molecular Biology Related Procedures

Purification of ZIKV viral protein complexes

NSCs were electroporated with 3xFlag-tagged plasmids encoding each ZIKV protein (Protein ID: BAP47441.1 for polyprotein) by Neon® Transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the following parameters (Pulse voltage: 1,300 s; Pulse width: 10 ms; Pulse number: 3; Cell density: 107 cells/ml). 5×107 NSCs were harvested in 10 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P40, 10% glycerol, phosphatase inhibitors and protease inhibitors) at 72 h post electroporation, followed by centrifugation and filtration (0.45 μm) to remove debris. Cell lysates were precleared with 100 μl protein A/G resin, and then incubated with 25 μl anti-Flag M2 resin (Sigma, #F2426) for 12 h at 4°C on a rotator. The resin was washed 5 times and transferred to a spin column with 40 μl of 3 X Flag peptide (Sigma, #F4799) for 1 h at 4°C on a rotator. The purified complexes were loaded onto a 4–12% NuPAGE gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #NP0321). The gels were stained with a SilverQuest staining kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #LC6070), and lanes were excised for mass spectrometry analysis by the Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA).

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, #74106) and treated with RNase-free DNase according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All gene transcripts were quantified by quantitative PCR using qScript™ One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (Quanta Biosciences, #95057–050) on CFX96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences are listed in Table S5.

Quantification of miRNAs by real-time PCR

Profiling of mature forms of miRNAs in AAV-GFP-, AAV-CapsidWT-, or AAV-CapsidH41R- infected E18.5 brain tissues was performed using TaqMan Advanced miRNA assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A25576) on StepOne Plus Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 20 ng total RNA was used for preparing cDNA templates including poly(A) tailing, adaptor ligation, reverse transcription and miRNA amplification steps (14 cycles) using the TaqMan Advanced miRNA cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A28007), following the manufacturer’s instructions. TaqMan miRNA real-time PCR reactions were performed on StepOne Plus Real-time PCR system, in triplicates for each sample. The 20 μl reaction volume consisted of 2x TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (10 μl), 20x TaqMan Advanced miRNA Assay (1 μl), 4 μl nuclease free water and 5 μl of amplified miRNA. RT-PCR reactions were performed according to the standard protocol with 95°C for 20 s for enzyme activation first, and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 1 s for denature and 60°C for 20 s for annealing and extension. Assays used for mature miRNAs let-7, miR-9, miR-17, miR-19a, and miR-451 were: mmu-let-7a-5p (assay ID: 000377), mmu-miR-9–5p (assay ID: 000583), mmu-miR-17–3p (assay ID: 002308), mmu-miR-19a-3p (assay ID: 000395), and mmu-miR-451 (assay ID: 001141). Assays used for precursor miRNAs let-7, miR-9, miR-17, miR-19a, and miR-451 were: mmu-let-7a-1 (assay ID: Mm03306744_pri), mmu-mir-9–1 (assay ID: Mm04227702_pri), mmu-mir-17–1 and mmu-mir-19a-1 (assay ID: Mm04228426_pri), and mmu-mir-451 (assay ID: Mm03307525). Relative quantities of miRNA were determined using the Applied Biosystems real-time PCR Analysis Modules and standard ΔΔCt method, by normalizing to an endogenous control assay (U6 snRNA, assay ID: 001973).

Purification of GST recombinant protein

For expression and purification of recombinant GST-fusion proteins, GST-capsidSPH, GST-capsidIbH, GST-capsidH41R, and the negative control GST protein were expressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) at 30°C in the presence of 0.5 mM IPTG. Cell pellets were resuspended in GST lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 20 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0]) supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche, #4693159001), followed by sonication, and then the cell debris was removed by centrifugation (15,000 rpm, 4°C) for 30 min. The proteins in the supernatant were purified by glutathione sepharose (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and the purified proteins were quantified by a UV-visible spectrophotometer and BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #23227).

In vitro Dicer cleavage assay

For in vitro Dicer cleavage of dsRNA, dsRNA-GFP primers fused with the T7 5’-tail sequence (underlined) were designed (GFP-forward 5’-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGAGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGCTG-3’ and GFP-reverse 5’-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGAGTAGTGGTTGTCGGGCAGCAG-3’), and standard PCR was performed using a GFP cDNA clone as template. The resulting amplicons were purified with GeneJET PCR Purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #K0702) and 1 μg used as templates for dsRNA-GFP synthesis using the T7 transcription kit and purified following the protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #AM1333). The resulting dsRNA-GFP products were subjected to a denaturation step at 98°C for 5 min, followed by 30 min at room temperature. 0.5 μg of 600-nt dsRNA was incubated with 1 U of a recombinant turbo human Dicer (Genlantis, #T510002) and GST-fusion proteins (1, 2.5, or 5 μg) in total 10 μl volume with reaction buffer provided by the manufacturer at 37°C for 2 h. Dicer cleavage of dsRNA that results in an increase of small dsRNA fragments were purified from the reaction complex by RNA purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The dsRNA products were subject to both bioanalyzer and agarose gel electrophoresis. The bioanalyzer electrophoresis could distinguish differentiated sizes of dsRNA fragments, as produced by in vitro Dicer cleavage of dsRNA (Figure S3F). In theory, Dicer cleaves one copy of 600-nt dsRNA to produce ~26 copies of small dsRNA; which is equivalent to 25 fold increase in DNA fragment numbers. Based on this, a strand curve of relative dsRNA fragments (fold change) with dsRNA size was drawn between conditions with or without 1 U of Dicer (Figure S3G), which confirmed a fold increase of ~25 with complete Dicer cleavage (Figures S3F–G).

In vitro ShortCut RNase III cleavage assay

We used 1 U ShortCut RNase III (NEB, #M0245S) to digest the dsRNA in vitro for 1 h, following the manufacturer’s instruction.

Capsid-dsRNA binding assay

dsRNA (~100nt) was synthesized by GenScript with 5’-Biotin labeling on one strand, and 100 μl Biotin-dsRNA with increasing concentration was inoculated on Streptavidin Coated High Capacity Plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #15500) overnight at 4°C. After blocking with 5% BSA at room temperature for 2 h, 100 μl recombinant GST, GST-capsidWT, or GST-capsidH41R (10 μg/ml) was added into each well at room temperature for 20 min, followed by 5-time washing with PBST, and mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-138) was added to detect the dsRNA-associated recombinant GST proteins with standard ELISA protocol.

Immunoblotting

Brain tissue or cell lysates were collected in 1% NP40 buffer with the protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, #4693159001) and phosphatase inhibitor PhosSTOP (Roche, #4906845001), and protein amounts were quantified by BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #23227). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane by semi-dry transfer at 25V for 30 min. All membranes were blocked in 5% milk in PBST for 1 h and probed overnight with indicated primary antibodies in 5% BSA at 4°C. Primary antibodies included: mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-47778), mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Biolegend, #901503), rabbit polyclonal anti-HA antibody (Biolegend, #923502), rabbit polyclonal anti-Myc antibody (Abcam, #ab9106), rabbit monoclonal anti-V5 antibody (R&D Systems, #MAB8926), mouse monoclonal anti-Flag antibody (Sigma, #F1804), rabbit polyclonal anti-Flag antibody (Sigma, #F7425), mouse monoclonal anti-GST antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-138), rabbit polyclonal anti-ZIKV capsid antibody (GeneTex, #GTX133317), rabbit polyclonal anti-ZIKV envelope antibody (GeneTex, #GTX133314), rabbit polyclonal anti-Dicer antibody (Cell Signaling, #5362), mouse monoclonal anti-Dicer antibody (Novus Biologicals, #NBP2–30699) Appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were incubated on membranes in 5% milk and bands were developed with G:BOX Chemi XX6 gel doc system (Syngene) and analyzed in Image Lab software.

Cellular Biology Related Procedures

Reversal-of-silencing assay

HEK293T cells were seeded in 12-well plate and transfected with 0.3 μg GFP expression plasmid and 0.3 μg GFP-specific shRNA in the presence of 0.5 μg capsids of ZIKV, DENV2, WNV, JEV, HCV, OHFV, and TEBV, or ZIKV capsid H41R mutant, or capsid from SPH2015 or IbH30656 strain. Live-cell imaging performed at 48 hr post-transfection using the BZ 9000 all-in-one Fluorescence Microscope from Keyence equipped with Phase-contrast (Osaka, Japan) and analyzed using NIH ImageJ software. The shRNA activities were quantified according to GFP expression levels after normalized to control condition transfected with only GFP and vector control.

Dual luciferase Let-7a reporter assay

HEK293T cells were seeded into 12-well plates. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were transfected with 100 ng of let-7a reporter plasmid and 10 ng of firefly luciferase plasmid, together with increasing amounts of plasmids encoding vector, ZIKV SPH2015 strain capsid, ZIKV capsid-H41R, DENV2 capsid, WNV capsid, or ZIKV IbH30656 strain capsid. Forty-eight hours after transfection, whole-cell lysates were prepared and subjected to the Dual-Glo luciferase assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Results are presented with Renilla luciferase levels normalized by the firefly luciferase levels.

Neurosphere formation assay

NSCs were dissociated using StemPro Accutase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A1110501), following manufacturer’s instruction. Single cell suspensions were obtained using 40 μm cell strainers (Stemcell Technologies, #27305). 1×105 NSCs were seeded in 6 well plates, treated with ZIKV or lentiviruses within 24 h after seeding, and the numbers of neurospheres (>30 μm) formed after 7 days of in vitro culture were counted for each condition, using an inverted light microscope (Keyence BZ-9000), as previously reported (Cloëtta et al., 2013; Keyoung et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2013).

Cell differentiation assay

NSCs were plated on poly-L-Orthithine (10 μg/ml) and laminin (10 μg/ml) coated 18 mm round cover glasses in 4-well plates at a density of 4 × 105 per well in DMEM/F12/N2 medium and incubated for 5 or 10 days in vitro (DIV) to allow for differentiation. Growth medium was changed every 3 days with addition of 50% fresh medium. At 5 DIV and 10 DIV, the cells were immunostained for neuronal markers MAP2 and astrocyte marker GFAP, using chicken polyclonal anti-cow MAP2 antibodies which cross-reacts with human MAP2 (Abcam, #ab5392, 1:500), mouse monoclonal anti-swine GFAP antibody which cross-reacts with human GFAP (Cell Signaling, #3670, GA5, 1:500), and Hoechst nuclear stain for the assessment of total number of cells. MAP2+ neurons and GFAP+ astrocytes were counted from 15 randomly selected fields from 3 independent experiments using NIH ImageJ software.

siRNA gene silencing

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting human Dicer (siRNA ID: s23754) and negative control siRNAs were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. siRNAs were delivered to the human NSCs using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #13778030) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h of transfection, cells were verified for target gene knock-down by quantitative RT-PCR or replaced with fresh medium for indicated virus infection.

Tissue Related Procedures

Viral inoculation of embryonic brains via in utero injection

For timed pregnancy in mice, noon of the day after mating is considered embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). The 13.5-day-pregnant C57BL/6J mice (JAX stock #000664) were anesthetized by 2% isoflurane. Disinfection was performed by iodine and 70% ethanol at abdomen of the mice, where 1 cm length window made the fetus exposed for injection. For ZIKV injection, 1 μl (equivalent to 500 PFU) of ZIKV strain SPH2015 (WT), ZIKV-H41R mutant virus, chimeric ZIKV-SPHNPL, IbH30165 strain, or culture medium as vehicle (DMEM + 2% FBS) were injected into lateral ventricle (LV) of embryonic littermate brains as described previously (Li et al., 2016a; Yuan et al., 2017). For AAV injection, 1 μl (equivalent to 5×108 vg) of AAV9-capsidWT, AAV9-capsidH41R, or AAV9-GFP were injected into LV of embryonic littermate brains. After injection, embryos were placed back to pregnant dams, and suturing for inner muscle and outer skin were separately performed. These mice were monitored every day until E16.5 or E18.5. E18.5 embryonic heads were collected and fixed overnight in 4% PFA. On the next day, the embryonic brains were dissected from the heads and were subjected to be taken images using a Stereo Microscope (Leica, M165 FC). The brain width (mm) were automatically measured using Leica Application Suite X (LAS X). Isolated brains from E16.5 or E18.5 embryos were sectioned for in situ hybridization or tissue staining.

To knockdown Dicer in mouse embryonic brain, we used Dicer-specific double-stranded Ambion In vivo siRNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #4457302), which has superior effectiveness and stability in vivo and can effectively suppress gene expression within 24 h with the effect lasting for more than two weeks after a single infection when used with Invivofectamine reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #IVF3001). Ambion In vivo siRNA was reconstituted in Invivofectamine 3.0 reagent and diluted in PBS; a final dose of 0.1 nmol in 1 μl containing 500 PFU of indicated virus was delivered to E13.5 ventricles using a Hamilton syringe over 5 min. The knockdown efficiency of Dicer-specific siRNA compared to scrambled siRNA was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR, which indicated 71% inhibition of Dicer mRNA in the brain.

For measuring cortical area or body length, cortical area or body length was carefully indicated as a closed circle or line in Image J software by freehand selection, and area size or line length was measured three times and the averaged value were recorded for each embryo.

Detection of Apoptosis

Live/Dead cell viability assay was performed using the LIVE/DEAD® Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit, for mammalian cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #L3224), following the manufacturer’s instruction. Apoptotic cells were visualized by in situ terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated digoxigenin-dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay according to manufacturer’s instructions (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein, Roche, #12156792910). Cells were counterstained with the DNA binding fluorescent dye, Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The rate of apoptosis was expressed as a percentage of TUNEL+ cells for the cell type studied. The cells were counted in 15 randomly selected fields from 3 independent experiments using NIH ImageJ software.

RNAscope in situ hybridization

ZIKV RNA was detected using gene-specific probe (Advanced Cell Diagnotics, #464531) and visualized using the RNAscope 2.5 HD Reagent Kit RED (Advanced Cell Diagnotics, #322360) on 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixed frozen E18.5 brain tissue sections, according the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin (Vector Laboratories, #H3401). Sections were imaged and stitched using the BZ 9000 all-in-one Fluorescence Microscope from Keyence (Osaka, Japan), and analyzed using NIH Image J software.

Tissue staining and confocal microscopy

At endpoint, E16.5 or E18.5 fetuses were fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C. For cryosectioning, fixed tissues were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4°C and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (VWR, #25608–930). Cryostat sections were cut at 20 μm thickness. For vibratome sectioning, fixed brains were embedded in 5% low melt agarose and cut at 30 μm thickness. Three comparable cryosections from each brain at 100 μm intervals were immunostained. Brain sections were permeabilized in PBS-T (PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100) for 10 min, blocked with 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, #017-000-121) for 60 min and incubated in primary antibody diluted in the blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies used in this study include rabbit anti-ZIKV capsid (GeneTex, #GTX133317), rat anti-CTIP2 (Abcam, #ab18465), mouse anti-SATB2 (Abcam, #ab51502), rabbit anti-TBR1 (Abcam, #ab31940), rat anti-SOX2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #14-9811-80), Rabbit anti-cleaved Caspase3 (Cell Signaling, #9661), Rabbit anti-Doublecortin (Cell Signaling, #4604), Rabbit anti-PAX6 (Abcam, #ab5790), Rabbit anti-TBR2 (Abcam, #ab23345), Mouse anti-flavivirus group antigen (Millipore, #MAB10216), Rabbit anti-phospho-histone H3 (Cell Signaling, #9710), and Rabbit anti-Ki67 (Abcam, #ab15580). After three washes with PBS, sections were incubated with the secondary antibodies for 1 h, including Alexa 568-conjugated donkey anti-mouse (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A10037), Alexa 647-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A-31573), and Alexa 488-conjugated donkey anti-rat (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A-21208). All images were taken with the Nikon A1R confocal microscopy and analyzed using NIH ImageJ software.

For quantification, cortical area perpendicular to the lateral ventricle in each section was imaged, and the number of CTIP2+, SATB2+ or TBR1+ neurons were counted automatically using the Cell Counter plug-in in ImageJ. The number of each type of the neuron was expressed as cell number per mm2, and values of cell number from three sections per brain were averaged to represent one dot in the plot.

Viral plaque assays

Cells were plated at a density of 5.0 ×104 cells/well in 1ml DMEM, 10% FBS, on 24-well plates and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 atmosphere. On the next day, 300μl of appropriate ten-fold dilutions (usually ranging from undiluted to 10−7-fold diluted) of supernatants from infected cultures were added to each well. After incubation of 1 hour, supernatants were discarded and the Vero cells layer were rinsed and overlaid with 0.7% methylcellulose. After incubation of 3 days, the overlaid methylcellulose was discarded, and the Vero cell layer was fixed and stained with Crystal Violet. Virus content of the supernatants was calculated as plaque forming units (PFU)/ml.

Phylogenetic tree

Capsid protein sequences from NCBI (ZIKV: YP_009430295.1; DENV2: AKS29276.1; WNV: YP_932082.1; JEV: NP_775663.1; YFV: NP_775999.1; TBEV: ALO78897.1; OHFV: NP_932082.1) are aligned by ClustalW (https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw) and phylogeny analysis was performed by likelihood tree method using Mega-X software.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as Mean ± SEM or Mean ± SD as indicated. For parametric analysis, the F test was used to determine the equality of variances between the groups compared; statistical significance across two groups was tested by Student’s t-test; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test were used to determine statistically significant differences between multiple groups. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. ZIKV-host protein interactomes in NSCs, Related to Figure 1

Table S2. Comparison of host targets from three ZIKV-host interactomes, Related to Figure 1

Table S3. Complete mass spectrometry data, Related to Figure 1

Table S4. Top 138 down-regulated miRNAs in ZIKV-WT-infected NSCs, Related to Figure 7

Table S5. Primer sequences used in this study, Related to STAR Methods

Figure S1. Interactome between individual ZIKV protein and its host targets, Related to Figure 1

Figure S2. Dicer interacts with ZIKV capsid, Related to Figures 1 and 2

Figure S3. ZIKV capsid inhibits Dicer’s activity via its H41 site, Related to Figure 2

Figure S4. ZIKV capsid is necessary to drive neuropathogenesis by targeting Dicer, Related to Figures 3 and 4

Figure S5. ZIKV Capsid is sufficient for causing neurogenic deficits, Related to Figure 5

Figure S6. ZIKV epidemic strain shows stronger neuropathogenesis than African strain by targeting Dicer, Related to Figure 6

Figure S7. ZIKV suppresses host miRNA expression by targeting Dicer in NSCs, Related to Figure 7

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin | Santa Cruz | Cat #sc-47778 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Dicer | Novus Biologicals | Cat #NBP2–30699 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Dicer | Cell signaling | Cat #5362 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Myc | Abcam | Cat #ab9106 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Flag | Sigma | Cat #F1804 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Flag | Sigma | Cat #F7425 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-HA | Biolegend | Cat #901503 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-HA | Biolegend | Cat #923502 |