Abstract

Objectives

Early detection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) represents the most significant step towards the treatment of this aggressive lethal disease. Previously, we engineered a pre-clinical Thy1-targeted microbubble (MBThy1) contrast agent that specifically recognizes Thy1 antigen overexpressed in the vasculature of murine PDAC tissues by ultrasound (US) imaging. In this study, we adopted a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) site-specific bioconjugation approach to construct clinically translatable MBThy1-scFv and test for its efficacy in vivo in murine PDAC imaging and functionally evaluated the binding specificity of scFv ligand to human Thy1 in patient PDAC tissues ex vivo.

Materials and Methods

We recombinantly expressed the Thy1-scFv with a carboxy-terminus cysteine residue to facilitate its thioether conjugation to the PEGylated MBs presenting with maleimide functional groups. After the scFv-MB conjugations, we tested binding activity of the MBThy1-scFv to MS1 cells over-expressing human Thy1 (MS1Thy1) under liquid shear stress conditions in vitro using a flow chamber set up at 0.6 mL/minute flow rate, corresponding to a wall shear stress rate of 100 seconds−1, similar to that in tumor capillaries. For in vivo Thy1 US molecular imaging, MBThy1-scFv were tested in the transgenic mouse model (C57BL/6J - Pdx1-Cretg/+; KRasLSL-G12D/+; Ink4a/Arf−/−) of PDAC, and in control mice (C57BL/6J) with L-arginine-induced pancreatitis or normal pancreas. To facilitate its clinical feasibility, we further produced Thy1-scFv without the bacterial fusion tags and confirmed its recognition of human Thy1 in cell lines by flow cytometry and patient PDAC frozen tissue sections of different clinical grades by immunofluorescence staining.

Results

Under shear stress flow conditions in vitro, MBThy1-scFv bound to MS1Thy1 cells at significantly higher numbers (3.0 ± 0.8 MB/cell; P<0.01) compared to MBNon-targeted (0.5 ± 0.5 MB/cell). In vivo, MBThy1-scFv (5.3 ± 1.9 a.u.) but not the MBNon-targeted (1.2 ± 1.0 a.u.) produced high US molecular imaging signal (4.4-fold vs. MBNon-targeted; n=8; p<0.01) in the transgenic mice with spontaneous PDAC tumors (2 – 6mm). Imaging signal from mice with L-arginine-induced pancreatitis (n=8) or normal pancreas (n=3) were not significantly different between the two MB constructs and were significantly lower than PDAC Thy1 molecular signal. Clinical grade scFv conjugated to AlexaFluor-647 dye recognized MS1Thy1 cells but not the parental wild-type cells as evaluated by flow cytometry. More importantly, scFv showed highly specific binding to VEGFR2-positive vasculature and fibroblast-like stromal components surrounding the ducts of human PDAC tissues as evaluated by confocal microscopy.

Conclusions

Our findings summarize the development and validation of a clinically relevant Thy1 targeted US contrast agent for the early detection of human PDAC by US molecular imaging.

Keywords: Thy1, Ultrasound, Microbubbles, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Early Detection, Molecular Imaging, Endothelial cells

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of pancreatic cancer in the United States is on the rise, and the disease is projected to become one of the top three most common cancer types, along with lung and liver cancer, contributing to cancer-related deaths by 2030.1 Particularly, less than 20% of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) are eligible for curative surgical resection procedure because of the advanced nature of disease at the time of diagnosis.1 According to the 2020 American Cancer Society reports, only 10% of total PDAC cases at diagnosis have localized disease, and the five-year survival of this disease from its diagnosis is just 37%, suggesting a critical need to accurately detect early tumors before their malignant transformation and metastatic spread. PDAC is frequently asymptomatic until the late stages, making it extremely challenging for early detection. There are now well-defined high-risk populations, such as patients with chronic pancreatitis, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) and likely diabetics.2–4 New and highly sensitive methods of disease detection based on blood biomarkers, circulating tumor DNA, and molecular imaging are also underway.5 It is encouraging to see that the imaging-based screening trials of high-risk individuals with genetic predisposition to PDAC already show modest benefits in early detection.6–8

Combination of molecular markers that accompany the natural evolution of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia-3 (PanIN-3), the most common precursor of PDAC, and clinical imaging tools is a promising area of research in accurate and early detection of PDAC. Transabdominal ultrasound (US) imaging for pancreatic diseases including cysts, pancreatitis, and PDAC is initially recommended when the causes of general abdominal symptoms (dull pain in the upper abdomen that radiates to the back, bloating, and loss of appetite) are unclear. However, the quality of pancreas images with transabdominal US is highly operator dependent and is often impaired by overlying intestinal gas and obesity. If the physician suspects cancer, endoscopic US (EUS)-guided tissue imaging or biopsy provides the most sensitive method of detecting the underlying conditions.7 For the screening of asymptomatic high-risk individuals, a multimodality imaging approach showed a substantial agreement between EUS and MRI for a localized pancreatic lesion smaller than 1 cm in diameter.9,10 Although EUS is minimally invasive, it requires sedation or general anesthesia, which may produce pulmonary or cardiac risks in some patients. Contrast-enhanced US is a promising imaging technology with a high potential to detect and aid human pancreatic cancer treatment using contrast agents.10–12 A pooled meta-analysis of contrast-enhanced transabdominal US and EUS showed high sensitivity (0.89) and specificity (0.84) for the diagnosis of PDAC.13

US contrast agents are microbubbles (MBs) with a gas core (1 – 5 μm in diameter) and outer shell composed of lipids or proteins or both.14,15 Although MBs can be generally used as blood pool contrast agents, they can also be used for targeting by incorporating tumor vasculature associated antigen binding ligands on their shell.16,17 Targeted MBs remain within the vascular compartment because of their size, while specifically accumulating at the site of antigen expression on the endothelial cells, allowing greater ability to visualize small tumors in contrast-mode US images. Further, the differential expression of antigens in tumor neovasculature compared to the inflammatory or surrounding normal tissues can increase specificity and be utilized to discriminate PDAC tumors from benign neoplasia or pancreatitis.10,18

Previously, the Thymocyte differentiation antigen (Thy1/CD90) glycoprotein was identified and validated as a novel US imaging biomarker for PDAC.19 Thy1 is expressed on the cell-surface in the endothelial and stromal (activated stellate cells) compartments of PDAC tissue.20,21 It is also expressed by the neoangiogenic vessels in other cancer types, such as glioma22 and melanoma.23 Endothelial Thy1 is shown to interact with integrins expressed by monocytes and circulating cancer cells in blood.24 Tissue microenvironment of precancerous PanIN3 lesions and PDAC tissues express higher levels of Thy1 (up to four-fold increase in PDAC-associated vessels by immunohistochemical scoring) compared to PanIN1/2, normal pancreas and pancreas with chronic inflammation (chronic pancreatitis).19,21 For the Thy1 molecular imaging of PDAC tumors, a recently engineered single-chain antibody fragment (scFv) ligand identified from a yeast display library was conjugated to commercially available streptavidin pre-clinical MBs (MBThy1-scFv; MicroMarker, VisualSonics) and used for abdominal US imaging of PDAC tumors in mice.25 Due to the long circulation half-life, slow tumor specific accumulation, and cost-intensive nature of full-length antibody production, construction of imaging agents with smaller antibody fragments such as scFv have become popular, including for the molecular imaging of pancreatic cancer.26 However, in this previous report, the scFv coupling chemistry involved biotin-streptavidin conjugation approach, which is highly immunogenic and cannot be used for clinical applications in humans.27,28 Furthermore, the MBThy1-scFv contrast agent was not clinically translatable due to the presence of tag sequences used for bacterial expression and purification in the ligands. scFv ligand devoid of bacterial sequences, large-scale production method in good manufacturing practice (GMP) facility, and strong binding and specificity confirmations to human PDAC tissues, are needed before the contrast agent can be used for clinical studies.

The aim of this study is to design a clinically translatable MB contrast agent (MBThy1-scFv) that can differentiate malignant PDAC tissue from normal pancreas by US molecular imaging. To advance the MBThy1-scFv towards US clinical applications, we improved the US contrast agent in several ways including: (i) validation of scFv binding to human tissue samples of various PDAC grades expressing Thy1, (ii) adoption of clinically approved thiol-maleimide chemistry27,29 for scFv conjugation to a biocompatible MB formulation, and (iii) confirmation of high specificity of MBThy1-scFv in imaging murine PDAC tumors compared to normal and L-arginine-induced pancreatic tissues25 by US imaging, as formulated in the flowchart (Figure 1A). The results of our study confirm the potential clinical utility of this technique for human PDAC diagnostics and in the design of MB contrast agents applicable in the wider context of US molecular imaging.

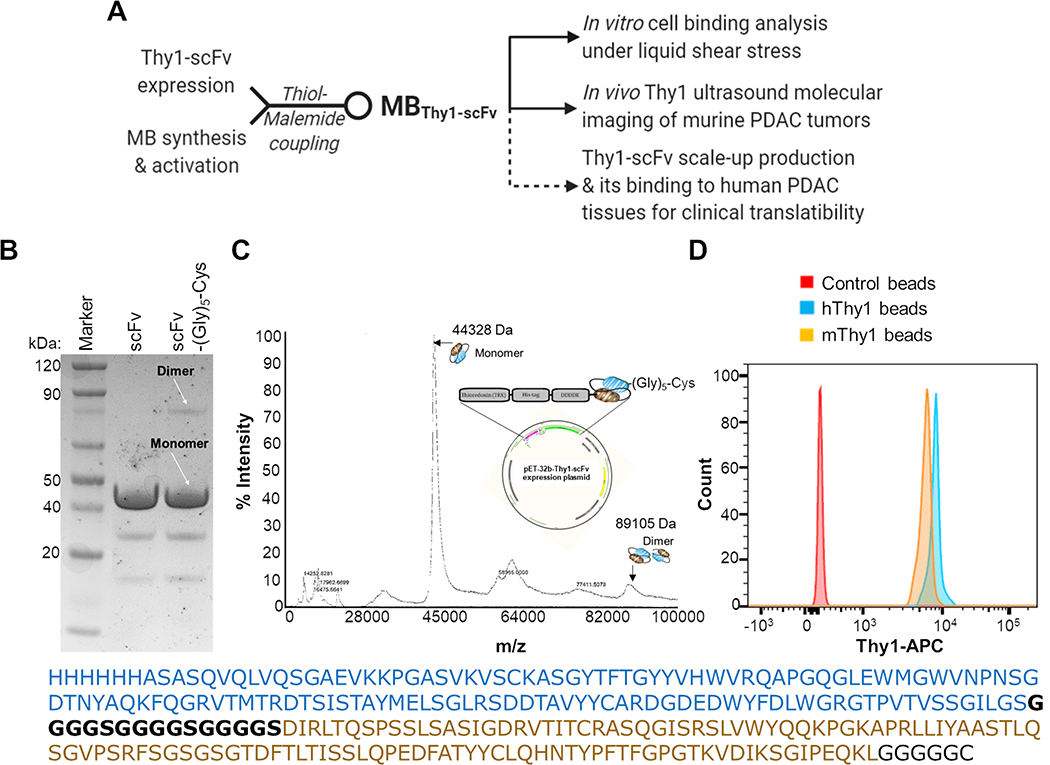

Figure 1. Characterization of the Thy1-specific scFv-(Gly)5-Cys.

(A) Flow-chart showing study design and pre-clinical validation work-up of Thy1-targeted microbubble (MB) contrast agent (MBThy1-scFv). Dotted lines represent validation experiments with only the scFv protein. (B) SDS-PAGE comparison of recombinantly produced scFv (with TrxA fusion protein) before and after the addition of C-terminal Cysteine (Cys) linked by a penta-Glycine linker (Gly5). A major band for the monomer form (~44 kDa) and a minor band for the dimer form (~89 kDa) are observed for scFv-(Gly)5-Cys in the non-reducing SDS-PAGE. (C) Mass Spectroscopy of the recombinantly expressed scFv-(Gly)5-Cys (with N-terminal TrxA and His6 fusion proteins as shown in the expression plasmid map) show a prominent singly charged species of scFv monomer (m/z = 44,328) and dimer (m/z = 89,105). Full sequence of the Thy1-scFv is provided with a heavy chain (blue) and a light chain (brown) separated by (G4S)3 linker sequence (black). (D) Flow cytometry based binding detection of the Dynabeads-immobilized 100 nM scFv-(Gly)5-Cys to the 66 pmol soluble human (h) or murine (m) Thy1 recombinant protein as detected by anti-Thy1-APC antibody. Naked beads without scFv was used as a negative control sample.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Wildtype MILE SVEN 1 (MS1WT) mouse vascular endothelial cells [CRL2279; American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)] were cultured (5 × 106 cells in 10 mL) under sterile conditions in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS and maintained in a 5% CO2 at 37°C. MS1 cells were transfected with human Thy1-expression plasmid and cells stably expressing human Thy1 (MS1Thy1) were selected by puromycin antibiotic marker as described before and used for different experiments performed in this study.19

Design and protein expression of Thy1 ligand

A yeast surface display nonimmune human scFv library was sorted and matured against human Thy1 protein as described elsewhere.25 We designed a pET-32b-based Thy1-scFv expression plasmid (GeneScript, Piscataway, NJ) with TrxA fusion protein sequence for enhanced protein folding and solubility, His6 tag for protein affinity purification, and KDDDD tag for enterokinase cleavage on the N-terminus of Thy1-scFv sequence. For the site-specific conjugation purposes, Thy1-scFv sequence included a Cysteine (Cys) on the C-terminus linked by a penta-Glycine (Gly)5 linker. 100 ng plasmid was used to transform 50 μL SHuffle T7 E. coli (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and bacterial colonies grown on agar plate containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin at 30°C. A single colony of bacteria was then expanded until OD600 of 0.6–0.8 in LB broth containing ampicillin at 30°C. Next, scFv-(Gly)5-Cys (44 kDa) recombinant expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) overnight at 30°C, bacteria lysed in buffer containing protease inhibitors (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), protein purified by HisTrap FF columns, and desalted/ concentrated using a 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff Vivaspin Protein Concentrator Spin Column (GE Healthcare Lifesciences, Pittsburgh, PA). The recombinant scFv-(Gly)5-Cys was examined for purity and size by Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) and SDS-PAGE analyses.

The scFv-(Gly)5-Cys (29 kDa) without the bacterial TrxA fusion protein was also commercially produced in E. coli with process optimization and scale-up as main criteria (Sino Biological Inc., Beijing, China). The ability of the thiol group on the terminal cysteine residue of scFv to react with a maleimide (MA) bearing moieties was confirmed. We tested this by the conjugation of the scFv {reduced by 10-fold molar excess of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP HCl) (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) at pH 7.0) with five-fold molar excess of AlexaFluor-647 C2 Maleimide (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) by incubating at ambient temperature for 1 hour. The excess unconjugated free AlexaFluor-647 dye from the scFv-(Glyc)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 conjugate was purified using BioGel® P-6 fine resin spin columns (Antibody conjugate purification kit; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR). The efficiency of conjugation and purity of scFv was then assessed by resolving 5 μg protein in SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie staining (SimplyBlue SafeStain, Carlsbad, CA). scFv size, purity, and AlexaFluor-647 (excitation: 650 nm; emission: 665 nm) labeling efficiency were also confirmed by gel visualization in a fluorescence imaging system (Odyssey, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) at 700 nm channel.

scFv(Gly)5-Cys binding to Thy1

Biotin binder Dynabeads (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) were used for the confirmation of scFv(Gly)5-Cys ligand binding activity to recombinant Thy1 protein. scFv was biotinylated (EZ-Link NHS-Biotin, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) at approximately 1:1 molar ratio and 100 nM of this ligand was immobilized to 25 μL biotin binder Dynabeads for 30 minutes. scFv-Dynabeads complex was incubated with 0 and 66 pmol of soluble IgG-Fc-conjugated recombinant human Thy1 (hThy1) or mouse Thy1 (mThy1) protein for one hour at 4°C (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). After washing the Dynabeads three times in PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (PBSA) on a magnetic column, scFv-bound Thy1 protein was detected by anti-Thy1-APC antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA; APC excitation: 650 nm; emission: 660 nm) based flow cytometry in the FACS Aria III system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).25

To confirm scFv binding to the cell-surface Thy1 by flow cytometry, MS1WT and MS1Thy1 cells (0.5 × 106/ 100 μL) were incubated with biotinylated scFv-(Gly)5-Cys (100 nM) or biotin-anti-Thy1 antibody (150 nM; eBioscience, Inc., San Diego, CA) for one hour at 4°C, washed three times in PBSA, and stained with streptavidin AlexaFluor-647 dye (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR). scFv binding activity was also confirmed by MS1WT and MS1Thy1 incubation with the scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 conjugate as a one-step method of binding detection. A positive control cell sample for Thy1 expression was prepared with the anti-Thy1 APC conjugated antibody incubation.

Synthesis and preparation of US contrast MBs

The phospholipids [1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DPPE), 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[carbonyl-methoxypolyethyleneglycol(polyethylene glycol)-5000] (DPPE-PEG(5000)-MPEG), and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[maleimide(polyethylene glycol)-5000] (DSPE-PEG(5000)-MA) or 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[carbonyl-methoxypolyethyleneglycol(polyethylene glycol)-5000] (DSPE-(PEG)(5000)-MPEG)] (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, AL) were dissolved in propylene glycol (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 70–75 °C for 30 minutes. Buffering salts were dissolved in glycerol and injectable water in separate containers at the same time. The two solutions were mixed and then distributed in 2 mL vials (1.5 mL added to each vial), sealed after filling with octafluoropropane (OFP) gas (Fluoromed, L.P., Round Rock, TX). We designed a special set-up chamber with a T-shaped tubing in which vials were filled with the OFP gas. One side of the T-shape tubing was connected to a vacuum pump while the other side was connected to OFP gas tank. All lines were controlled by separate valves that allowed them to be opened/closed at any time. Vacuum was applied to the chamber to remove air from the vials while the OFP gas line was closed. Then the chamber was pressurized with OFP gas while the vacuum line was closed. This process was repeated three times and then sealing rubber septa were pushed on the vial tops while they were still in the OFP gas chamber. The vials were then immediately taken out to further seal with metal lids using a manual crimper to ensure that the rubber septa did not pop up in atmospheric pressure. Vial batches with >90% OFP content that passed quality control by gas chromatography were then stored at 4°C until use. The vials for targeting MB contained DPPC, DPPE, DPPE-PEG(5000)-MPEG and DSPE-PEG(5000)-MA in the liquid suspension. The vials for control MB contained DPPC, DPPE, DPPE-PEG(5000)-MPEG and DSPE-PEG(5000)-MPEG. Additionally, DiOC18 fluorophore (excitation: 489 nm; emission: 505 nm) was added to the vials for MB detection in vitro by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry.

Stored vials at 4°C containing lipid mixture including DSPE-PEG5000-MA (for targeting) or DSPE-PEG5000-MPEG (control) were agitated as necessary by a Vialmix™ (Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc., North Billerica, MA) instrument for 45 seconds to form MBs just before the in vitro and in vivo experiments. Vials were then centrifuged (precooled at 4°C; 300xg) for 3 minutes.25 MBs (a white cake formed on the top of the solution) were separated from the solution by removing 1 mL of the clear bottom liquid with 22Gx1 1/2 needles (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) without disturbing the upper MB layer. 1 mL of fresh PBS buffer (degassed and precooled) was replenished into each vial along with 2–3 mL injection of OFP gas. Vials were gently agitated to mix the MBs in the solution and washed by centrifugation three additional times. The final MB solution was adjusted to 0.5 mL volume. Concentration and size distribution (by diameter) of synthesized MBs were determined on the Z2 Coulter Counter Analyzer (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, San Jose, CA) calibrated to detect MBs within the size range of 1–3 μm. Briefly, 10μL of MB solution was mixed evenly in 10mL buffer solution (Isoton II Diluent, VWR International, Visalia, CA) and size distribution was measured.

Conjugation of scFv-(Gly)5-Cys to MBs

For the preparation of Thy1 targeted MBs (MBThy1-scFv), MBs displaying MA reactive groups were used. scFv-(Gly)5-Cys was reduced (to ensure that all are in mono form with free cysteine) using TCEP HCl solution (10-fold molar excess) in degassed PBS at room temperature two hours prior to its incubation with targeting MBs. 0.5 mL of washed MBs solution was added to pre-reduced scFv (10-fold molar excess to DSPE-PEG(5000)-MA) in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube and incubated on a rocker at room temperature for two hours. The conjugated MBs were then washed in degassed PBS three times as described above. To confirm scFv(Gly)5-Cys conjugation to the MBs surface, a separate batch of scFv was biotinylated prior to its terminal cysteine reduction and incubation with the DiO-labeled targeting or control MBs, followed by washing and incubation with streptavidin- AlexaFluor-647 dye. The DiO dye-labeled MBs were gated and analyzed for scFv-labeling efficiency (AlexaFluor-647 signal) by flow cytometry (Guava easyCyte; Luminex Corp., Austin, TX) and fluorescence microscopy (Leica DMi8 microscope, Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL).

For the MA group-specific functionality of targeting MBs, we performed conjugation of MBs to BODIPY FL L-Cystine probe (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR). BODIPY-Cystine solution was prepared in PBS and reduced with TCEP HCl (5-fold molar excess). Reduced BODIPY-Cys was added to the targeting MBs with MA groups or control MBs with MPEG groups for one hour at room temperature. MBs were washed to separate unreacted BODIPY-Cys and analyzed for BODIPY signal comparison using flow cytometry (Guava easyCyte).

In vitro MBThy1-scFv binding to Thy1

Binding studies of targeted MBs [MBThy1-scFv; anti-Thy1-antibody (Ab) coated MBs (MBThy1-Ab)] and control MBs [scramble scFv-Cys coated MBs (MBscFv-scrambled); Isotype antibody coated MBs (MBNon-targeted)] to soluble recombinant human Thy1 protein were performed by flow cytometry. The DiO-labeled MBs were incubated with 20 nM soluble IgG-Fc-conjugated human Thy1 on a benchtop rotator for 40 minutes at room temperature. This was followed by washing the MBs by centrifugation at 300xg for three minutes in PBSA and incubation with anti-human IgG-Fc–AlexaFluor-647 antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes on ice with a final washing by centrifugation. DiO fluorescent signal threshold in the MBs was determined by gating a control MB sample without DiO labeling. Median fluorescence intensity data was analyzed by flow cytometry (FlowJo, Becton Dickinson, Ashland, OR).

In addition, we also performed a parallel-plate flow chamber assay (GlycoTech Corporation, Rockville, MD) using a syringe infusion pump where MBThy1-scFv or MBNon-targeted binding to MS1Thy1 cells grown on neutral charged culture slides was assessed at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/minute, corresponding to a wall shear stress rate of 100 seconds−1, simulating blood flow in tumor capillaries.19,25 PBS containing 5 × 106 MBs/mL in a total volume of 3 mL was infused and slides were then washed three times with PBS flow. A phase-contrast bright-field microscope (Axiovert 25; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY; original magnification, x100) was used to manually count the number of MBs attached to MS1Thy1 cells at five representative fields of view.

Mouse models for ultrasound (US) imaging

A transgenic pancreatic cancer mouse model (Pdx1-Cretg/+; KRasLSL G12D/+; Ink4a/Arf−/−) (n = 8), which spontaneously developed foci of pancreatic cancer within 4 to 7 weeks after birth 30, was used for US molecular imaging of focal lesions. Tumors between 1.5 and 4.5 mm (mean, 3.5 mm) in diameter based on US images were used in the study. Age-matched littermates without KRasG12D mutation were used as normal tissue control group (n = 3). Pancreatitis was established in C57BL/6J mice (n=8) using two intraperitoneal injections of L-arginine-HCl (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 0.9% saline separated by 1 hour interval once a week with increasing dosages (2, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, and 4 g/kg from weeks 1 through 6) followed by two weeks of recovery time before imaging.31,32

In vivo US molecular imaging of pancreas

The Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care approved all procedures using experimental animals. In vivo US imaging of vascular Thy1 expression in a transgenic mouse model of PDAC or C57BL/6 mice with normal pancreas or mice with L-arginine-induced pancreatitis using two MB constructs (MBThy1-scFv and MBNon-targeted) was performed by following the protocol reported previously.25 In brief, the animals were fasted for 24 hours prior to abdominal US imaging. A total of 5×107 Thy1-targeted or control non-targeted MBs in 100 μL volume was used for intravenous bolus injection via tail vein using a catheter with a 12cm PU tubing and a 27G butterfly needle (VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada). A 20-minute interval was maintained between each MB injections to allow for complete clearance of freely circulating MBs before subsequent imaging. All in vivo imaging studies were performed in contrast mode using a dedicated small-animal high resolution US imaging system (Vevo 2100, FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada) with the transducer placed over the abdomen of mice, guided by B-mode imaging to detect the target tissue of interest. Visualization of the pancreas was facilitated with 1 mL intraperitoneal injection of physiological saline. Contrast mode images were acquired with a 21-MHz linear transducer, and all imaging parameters (focal length, 10 mm; transmit power, 4%; mechanical index, 0.2; dynamic range, 40 dB and a center frequency of 21 MHz) were kept constant during all imaging sessions. A total of 4 minutes was allowed for MBs to attach to its target tissue before quantification of MBs binding by differential targeted enhancement (dTE) method. The dTE protocol consisted of 3 steps: (i) 200 frames of images capturing blood-vessel bound and unbound MBs within the region of interest, (ii) a high pressure destructive pulse (1-second continuous high-power destructive pulse of 3.7 MPa, transmit power, 100%; mechanical index, 0.63) to destroy all bound and unbound MBs, and (iii) an additional set of 200 frames to measure the signal intensity from the unbound MBs flowing into the region of interest immediately post destructive pulse. The difference in US imaging signal pre- and post-destruction corresponds to the Thy1 molecular signal from blood-vessel attached contrast agent, MBThy1-scFv or MBNon-targeted.

The Thy1 molecular imaging signals were quantified post imaging by dTE method with correction for breathing motion artifacts by using Vevo 2100 integrated analysis software (VevoCQ; VisualSonics). Corresponding B-mode US images were used to select the region of interest around PDAC tumors or normal/ pancreatitis tissues, which was then used to quantify the molecular imaging signal in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Thy1-scFv binding on PDAC patient tissue sections

Freshly frozen human pancreatic tissue sections from poorly to well-differentiated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma were obtained with written informed consent and institutional review board approval (University of Arizona Cancer Center Biospecimen Repository protocol #0600000609). All studies involving human subjects were conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines such as the Declaration of Helsinki. The ability of scFv to detect glycosylated-Thy1 expressed by the vascular endothelial cells and the fibroblasts of patient PDAC tissue sections was tested by immunofluorescence staining. For this purpose, the commercially produced scFv-(Gly)5-Cys was conjugated to AlexaFluor-647 dye using thiol-MA reaction (please see above for conjugation detail). Frozen tissue sections were rinsed with PBS for 10 minutes to remove the O.C.T. media. This was followed by tissue fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, washing three times in PBS, and blocking in PBS containing 5% normal goat serum for 2 hours at room temperature followed by overnight incubation with scFv-AlexaFluor-647 (2.5 μg/mL), and 1:200 dilution of rabbit anti-human VEGFR2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Tissue slides were washed three times in PBS and incubated with 1:300 dilution of goat-anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR; Alexa Fluor 488 excitation: 495 nm & emission: 519 nm) and mounted in ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR). Images were acquired in the SP5 upright confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL).

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test was applied to determine statistical significance (P<0.05) between groups and data expressed as Mean ± SD. Correlation analysis of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) expression data for Thy1 and endothelial/angiogenesis-related gene signature33 in pancreatic cancer (n=179) and normal pancreas (n=171) samples [data derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases] were performed with gene expression profiling interactive analysis (GEPIA2) tool.34

RESULTS

Characterization of MBThy1-scFv

We modified a previously engineered Thy1-scFv protein sequence25 for its enhanced solubility during E. coli expression by adding a N-terminal TrxA fusion domain and a C-terminal cysteine (Cys) residue followed by a penta-Glycine (Gly5) linker for a stable thioether linkage27 with US contrast agents. The recombinantly produced scFv-(Gly)5-Cys protein was highly pure as demonstrated by SDS-PAGE in non-reducing condition (expected weight 44,780 Da; Figure 1B) and MALDI analysis (observed weight 44,328 Da; Figure 1C). The addition of terminal Cys residue did not lead to significant dimer formation as seen by a dominant monomer fraction of scFv both in SDS-PAGE and MALDI analyses. The monomer/dimer relative intensity ratio was 8:1 by SDS-PAGE and 10:1 by MALDI analyses. Further, recombinant scFv-(Gly)5-Cys retained its ability to bind to its soluble target, human or mouse Thy1 protein, in vitro as evaluated by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 1D).

We prepared the targeting MB contrast agent for US molecular imaging with biocompatibility, echogenicity, and stability as central factors for its future clinical application.35 The phospholipid shell was formulated with DPPC, DPPE, DPPE-PEG(5000)-MPEG and DSPE-PEG(5000)-MA for targeting MB construct or DSPE-PEG(5000)-MPEG for control MB construct (Figure 2A). While the MA presents as thiol-reactive chemical group for the conjugation of MBs to antibodies or small affinity proteins at physiological pH, the core of the MBs contain an inert gas, OFP, with low diffusion coefficient.

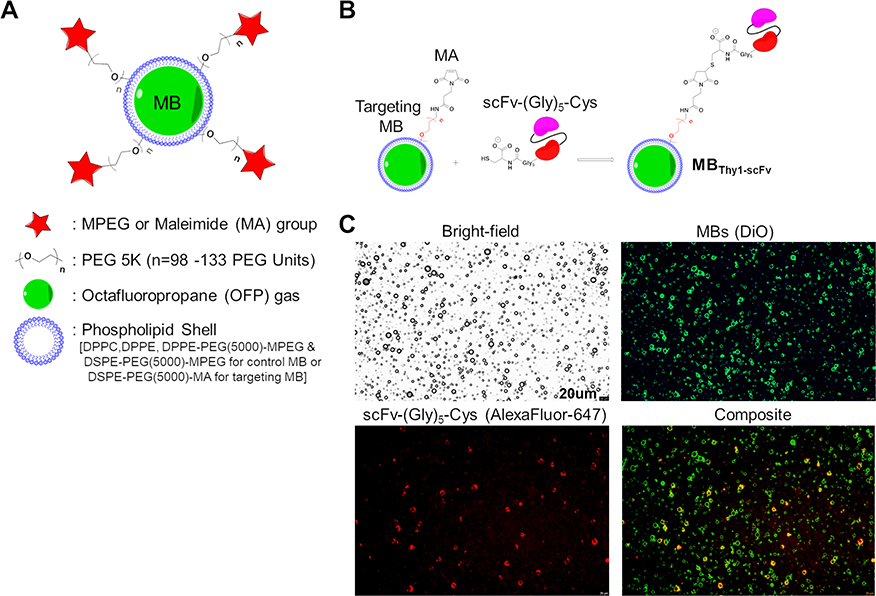

Figure 2. Characterization of MBs.

(A) A general schematic representation of the MBs with its functional components. A phospholipid shell composed of DPPC, DPPE and DSPE lipids surrounds a gas core consisting of octafluoropropane (OFP). A PEG chain (PEG5000) covalently attached to phospholipids enhances stability of the MBs while it also serves as a linker to bear an active Maleimide (MA) functional group for targeting by bioconjugation with proteins or neutral group (MPEG) in control MBs. (B) Schematic representation of thiol-MA coupling strategy to form the targeted MBs (MBThy1-scFv). C-terminal cysteine residue of the Thy1-specific scFv-(Gly)5-Cys is reduced for stable covalent bonding to the MA group in the DSPE-PEG(5000)-MA components of the targeting MB shell. (C) Bright-field and fluorescence images of MBThy1-scFv confirming the surface conjugation of scFv-(Gly)5-Cys onto the MB shell. A composite image shows biotinylated scFv-(Gly)5-Cys (red color; detected by streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 647) signal overlapping the DiO-labeled shell of targeting MBs (green color).

MBThy1-scFv contrast agent was prepared by thioether linkage of scFv-(Gly)5-Cys to the MA functional groups on the surface of targeting MBs (Figure 2B). First, the efficacy of this conjugation reaction was tested by incubation of targeting MBs consisting of DSPE-PEG(5000)-MA or control MBs consisting of DSPE-PEG(5000)-MPEG with reduced BODIPY FL L-Cystine fluorophore. Only MBs with surface MA groups could form thioether bond with BODIPY FL L-Cystine, resulting in green fluorescent signal (See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows efficient conjugation of BODIPY dye to MBs with MA functional groups by flow cytometry). Similarly, only the targeting MBs but not the control MBs attached to the reduced scFv-(Gly)5-Cys (See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows efficient and uniform conjugation of biotinylated-scFv to MBs with MA functional groups as detected by streptavidin-AlexaFluor flow cytometry). The conjugation steps did not cause significant changes in MBs diameter size (Targeting MBs: 2.0 ± 0.41 μm; Control MBs: 2.1 ± 0.5 μm) or numbers, (See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows MB size distribution and concentration by the particle size counter analyses), indicating no rapid gas dissipation or MB destruction occurs due to the addition of scFv to the MB surface. The MBThy1-scFv structure as well as the location and distribution of functional MA species on its surface were confirmed by fluorescent detection of conjugated scFv-(Gly)5-Cys protein on the DiO dye-labeled targeting MB shell (Figure 2C). Unlike the flow cytometry results (Supplemental Digital Content 2), the observation of MB targeting efficiency by fluorescence microscopy was less sensitive and showed varying levels of scFv-associated fluorescence intensity across the MB population.

MBThy1-scFv binds to Thy1 protein in vitro

Next, we compared the binding activity of Thy1-targeted contrast agents (MBThy1-scFv, MBThy1-Ab) and control contrast agents (MBscFv-scrambled, MBNon-targeted) against soluble human Thy1 protein by flow cytometry (Figure 3A). Both targeted MB constructs showed higher binding to biotinylated-Thy1 protein compared to the control MBs as detected by streptavidin-AlexaFluor-647 dye signal by flow cytometry. Under liquid shear stress conditions mimicking blood flow in tumor capillaries, significantly higher numbers (P<0.01) of MBThy1-scFv (3.0 ± 0.8 MB/cell) bound to MS1 cells overexpressing human Thy1 (MS1Thy1) grown on slides compared to the MBNon-targeted (0.5 ± 0.5 MB/cell) in a parallel plate flow chamber cell attachment assay (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. MBThy1-scFv specifically binds to Thy1 protein in vitro.

(A) Binding comparison of targeted MBs [MBThy1-scFv; anti-Thy1-antibody (Ab) coated MBs (MBThy1-Ab)] and control MBs [scrambled scFv coated MBs (MBscFv-scrambled); Isotype-antibody coated MBs (MBNon-targeted)] to 20 nM biotinylated human Thy1 (hThy1) protein by flow cytometry. DiOC18 fluorophore incorporated in MB shell was used to gate the micron-sized particles and detect associated streptavidin-AlexaFluor-647 dye signal from the MB bound biotinylated-Thy1 protein. Only MBThy1-scFv and the positive control MBThy1-Ab showed binding signal to the soluble Thy1 protein. (B) Upper panel: A simplistic schema of the flow chamber cell attachment setup shows controlled flow (0.6 mL/ minute) of MBs. MS1 cells overexpressing Thy1 (MS1Thy1) grown on a glass slide was inverted (curved arrow) with cells directly contacting the liquid containing MBs flowing at the set rate. Lower panel: Bar graph quantifications of MBThy1-scFv show significantly higher (P<0.01) number of MBs attached per MS1Thy1 cell compared to the MBNon-targeted under liquid shear stress conditions in flow chamber assay. Error bars represent standard deviation.

MBThy1-scFv differentiates PDAC from normal pancreatic tissue by ultrasound molecular imaging in vivo

We tested MBThy1-scFv contrast agent in vivo for its ability to enhance Thy1-specific US imaging signal in mouse models of PDAC, L-arginine-induced pancreatitis, and healthy pancreas. The MBThy1-scFv in the current study uses C-terminal cysteine site-specific conjugation strategy of scFv to MBs by using clinically applicable thiol-MA chemistry in reducing conditions. Prior to imaging, we tested for MB aggregation, size and concentration changes that may occur due to factors such as steric changes and gas dissipation after scFv conjugation. No significant changes in MBThy1-scFv size, concentration or aggregation was observed compared to the control MBs (See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2). Imaging of PDAC tumor foci (n=8) in the transgenic mice with MBThy1-scFv (5.3 ± 1.9 a.u.) showed significantly increased (4.4 fold; P<0.01) Thy1 molecular signal compared to imaging with MBNon-targeted (1.2 ± 1.0 a.u.) as analyzed by the destruction-replenishment quantification method of MB contrast signal (Figure 4A). Conversely, imaging of tissues with L-arginine-induced pancreatitis (n=8) (Figure 4B, 4C), or healthy normal pancreas (n=3) (Figure 4D) in mice did not produce any significant differences in imaging signal between the two MB constructs. Consistent with previous findings, mouse PDAC tumors but not the pancreatitis or healthy pancreatic tissues show vascular Thy1 expression in CD31-postive vasculature by immunofluorescence staining (data not shown).19,25

Figure 4. MBThy1-scFv enhances Thy1-specific ultrasound (US) molecular signal in murine PDAC tumors.

(A) Left: A transgenic mouse model (PDAC mouse model; n=8) injected with MBs via the tail vein for US imaging. Right: Representative transverse-section contrast mode ultrasound images and bar graph quantification show significantly (4.4 fold; P<0.01) higher imaging signal in PDAC tumors (green outline) with MBThy1-scFv (5.3 ± 1.9 a.u.) compared to imaging with MBNon-targeted (1.2 ± 1.0 a.u.). Thy1 differential targeted-enhancement (dTE) signal is represented as a colored overlay over the contrast-mode images. (B) Schematic treatment plan for L-arginine-induced pancreatitis in C57BL/6 mice (n=8). No significant (ns) differences in Thy1 imaging signal was observed in pancreatitis tissues with both MB constructs as shown in the dTE images (upper panel) and bar graph quantification (lower panel). B-mode images were used as reference to draw a region of interest (green outline) around the entire pancreas. (C). Bar graph show no significant (ns) difference in imaging signal in the normal pancreas (n=3) with both MB constructs. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Thy1-scFv specifically binds to Thy1 protein expressed on endothelial cells and human PDAC tissues

In order to construct a fully translatable contrast agent for human PDAC imaging, biocompatibility of both MBs and scFv are of utmost importance. Although the MBs used in our animal imaging studies are biocompatible, electrostatically neutral, and highly stable,36,37 the scFv moieties possess bacterial TrxA fusion protein for recombinant production of the scFv-(Gly)5-Cys, which may induce undesired immune response in humans. We optimized the scFv biocompatibility and scalability by removing the TrxA tag from its sequence and produced it commercially (Sino Biological). Characterization of commercially produced scFv-(Gly)5-Cys confirmed its purity and lower molecular weight (~29 kDa) (See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which shows highly pure form of the scFv monomer by SDS-PAGE). The ability of this scFv-(Gly)5-Cys to perform thioether conjugation chemistry with AlexaFluor-647 dye bearing a MA group was preserved (See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which shows dye-conjugated band of scFv in the fluorescence imaging mode of the SDS-PAGE gel). The 29 kDa scFv-(Gly)5-Cys binding specificity to its cell-surface target on MS1Thy1 endothelial cell line as confirmed by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence staining (Figure 5A–5C). Biotinylated-anti-Thy1 antibody confirmed expression of cell-surface Thy1 on the MS1Thy1 cells as detected by streptavidin-AlexaFluor-647 flow cytometry. Binding of both the biotinylated (Figure 5A, 5B) and dye-conjugated scFv (See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4, which compares scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 conjugate binding to MS1Thy1 and MS1WT cells) confirmed its specificity to cell-surface human Thy1 protein by flow cytometry. Direct immunofluorescence staining with the scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 conjugate also confirmed high binding specificity of Thy1-scFv to MS1Thy1 cells grown on culture slides (Figure 5C).

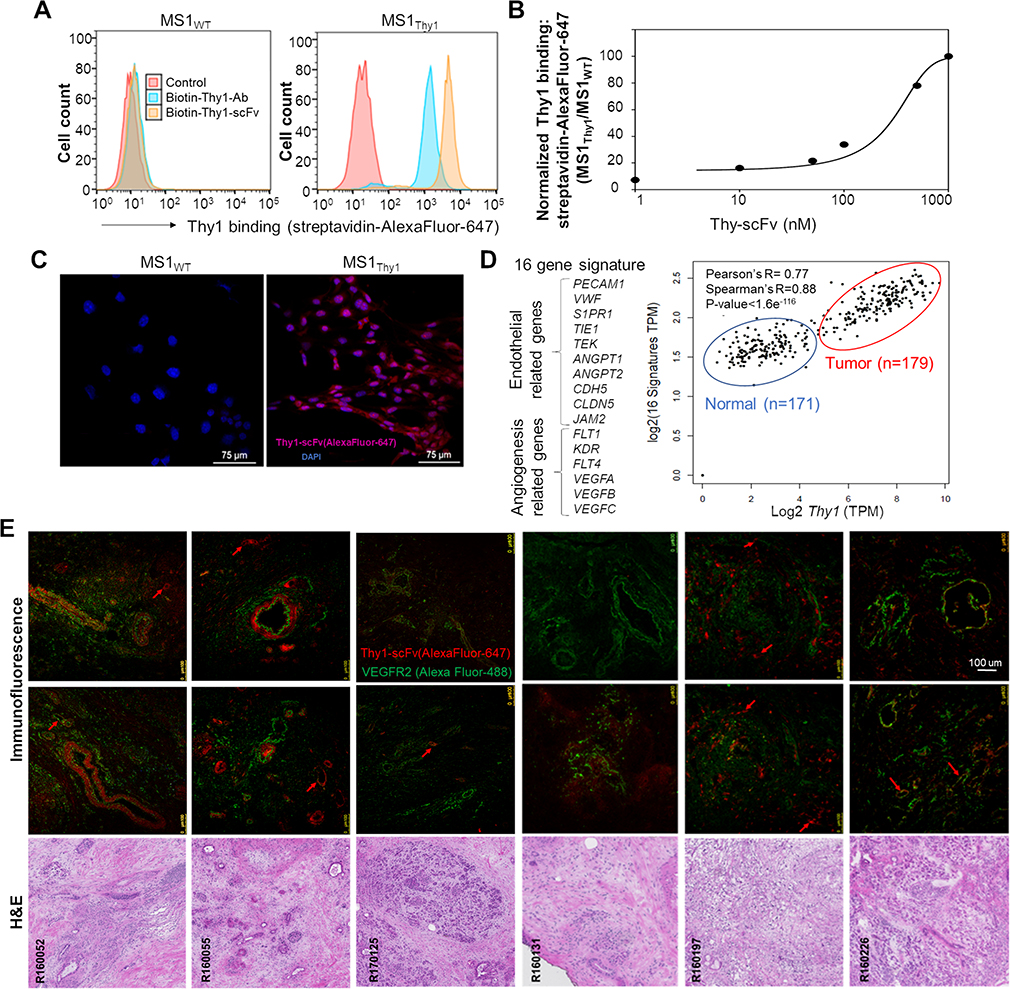

Figure 5. Validation of scFv-(Gly)5-Cys binding activity in cells and tissues expressing human Thy1.

The process of scFv (without TrxA fusion protein; 29 kDa) scale-up production was optimized in a commercial facility and binding specificity validated in vitro. (A) Flow cytometry histograms confirming binding specificity of biotinylated scFv-(Gly)5-Cys (100 nM) to MS1Thy1 cells by streptavidin-AlexaFluor-647 detection. 150 nM of a commercially available biotinylated—anti-Thy1-antibody (Ab) is used as a positive control for the confirmation of cell-surface Thy1 expression. Detection signal intensity of scFv and antibody binding could be affected due to differences in their biotinylation levels. (B) SigmaPlot of dose-dependent (0 – 1000 nM) normalized scFv-(Gly)5-Cys (biotinylated) flow cytometry binding signal (streptavidin-AlexaFluor-647) to MS1Thy1 cells relative to background MS1WT binding signal. (C) Immunofluorescence images of MS1 cells grown on slides confirm Thy1-binding specificity of scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 conjugate (red) to MS1Thy1 cells. Blue color indicates DAPI nuclear stain. (D) RNA-seq-based gene expression correlation analysis (Pearson’s R= 0.77; Spearman’s R=0.88) between Thy1 and endothelial/ angiogenesis gene signature (16 genes) in the human pancreatic cancer (red outline; n=179) and normal pancreatic (blue outline; n=171) tissue samples. Data available from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases. (E) Multi-panel immunofluorescence staining and corresponding H&E images of patient PDAC frozen tissue sections. The top and middle rows show representative staining with anti-VEGFR2 antibody (Alexa Fluor 488; green) and the scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 conjugate (red). VEGFR2 staining is used as a reference maker for vasculature and tumor cells. Note the incidences where co-immunostaining occurs (yellow color). Thy1-scFv stained mostly vasculature (red arrows) and cancer associated fibroblasts around the ducts in the tumor environment. Left to right: R160052 (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma); R160055 (invasive ductal adenocarcinoma); R170125 (invasive poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma); R160131 (invasive well-differentiated ductal adenocarcinoma); R160197 (poorly differentiated invasive ductal adenocarcinoma); R160226 (invasive ductal adenocarcinoma).

In our RNA-seq analysis of publicly available pancreatic cancer patient databases, Thy1 expression showed significantly high correlation (Pearson’s R = 0.77; Spearman’s R= 0.88) with 16-gene signature associated with endothelial (PECAM1, VWF, S1PR1, TIE1, TEK, ANGPT1, ANGPT2, CDH5, CLDN5, JAM2) and angiogenesis (FLT1, KDR, FLT4, VEGFA, VEGFB, VEGFC) markers, suggesting its expression increases with the microvascular density in the human PDAC microenvironment (Figure 5D).33 In order to examine Thy1 protein expression and the binding efficacy of its engineered ligand to its heavily glycosylated form in the PDAC tissue microenvironment,20,38 we performed immunofluorescence staining of frozen human PDAC tissues with the scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 conjugate. (Figure 5E). In addition, anti-VEGFR2 antibody co-staining was performed to detect both the neoplastic epithelial and endothelial compartments. VEGFR2 positive staining was observed in the blood vessels as well as the tumor cells in ductal lining as well as extra-ductal regions in the tissue samples with invasive disease. The commercially produced Thy1-scFv showed strong tissue staining signal in the areas surrounding the ductal structures, which include Thy1-positive myofibroblasts.39 More importantly, scFv positively stained the Thy1 protein in the tumor associated vascular structures (Figure 5E). Together, these results confirm that the Thy1-scFv production can be scaled up and it specifically binds to the human Thy1, both in the fibroblasts and endothelial cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we designed and further developed a previously engineered25 human Thy1-specific scFv ligand and incorporated it into a clinically translatable US contrast agent to produce MBThy1-scFv for molecular imaging of PDAC. We characterized the scFv binding activity to cells expressing Thy1 in vitro and human PDAC tissue samples of different grades ex vivo, optimized clinically applicable thioether conjugation chemistry to produce MBThy1-scFv, and applied the contrast agent for US molecular imaging of PDAC tumors, pancreatitis, and healthy pancreas in mouse models.

Imaging-based screening of patients with symptoms suggestive of early PDAC or those in high-risk groups is currently performed with variety of abdominal imaging tools.40 The detected abnormality may represent inflammation, benign lesion or pancreatic malignancy. CT scan usually detects only advanced-stage pancreatic cancer while EUS can detect pancreatic lesions as small as 2 – 3 mm in size;41 however, these findings are of unknown significance without incorporating invasive EUS-guided biopsy procedures. Additionally, in patients, the pancreas is difficult to evaluate with transabdominal US due to the interposition of intestinal gas between the transducer and the pancreas. Established diagnostic protocols recommend operators to adjust transducer position and pressure to achieve a clear acoustic path to the pancreatic tumor due to technical difficulties presented by intestinal gas or overlying layers of fat in obese patients.42 Functional techniques that can measure tumor tissue stiffness such as US time-harmonic elastography and harmonic motion imaging are clinically feasible for deep tissue investigation to assess suspected PDAC lesions that are not otherwise apparent with traditional US.43,44 Blood pool contrast agents also aid in the detection of focal abnormalities in conjunction with techniques such as tissue harmonic US imaging in obese patients45 and contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS targeting deeper tissues such as the pancreas.46 Meta-analyses of data from a multicenter pancreatic US imaging study showed that the contrast-enhanced US/EUS has 90% accuracy in differentiating PDAC from other etiologies of suspected pancreatic lesions as supported by biopsy and histopathological evaluations.47 US molecular imaging with contrast MBs that are targeted to molecules (examples: VEGFR2 and Thy1) expressed by the tumor vasculature substantially increase the ability of US to detect and characterize small foci, thus allowing a non-invasive differential diagnosis based on molecular features that distinguish early PDAC from benign conditions such as early PanINs and IPMNs, as well as pancreatitis.40,41,48,49 Although clinical grade VEGFR2-targeted (BR55) MBs have shown promise in differentiating benign and malignant tumor lesions in human clinical trials,50 its specificity for imaging human PDAC tumors remains to be determined. A phase 2 clinical trial is underway (Clinical Trials Identifier: NCT03486327) to characterize pancreatic lesions in subjects with suspected PDAC using BR55 MBs by transabdominal US imaging. With the goal of obtaining a PDAC-specific contrast agent targeting human Thy1, a biomarker differentially expressed in PDAC neovasculature compared to precursor lesions, we modified a previously engineered Thy1-scFv ligand25 and utilized it to produce a clinically translatable Thy1-targeted MBs aimed at early and accurate detection of human PDAC tumors.

Many humanized antibodies have been adapted as molecular imaging probes for high specificity pancreatic cancer imaging.26 However, the development and production of full-length antibodies is expensive and time-consuming, and it is also important to evaluate their long blood circulation time and slow tumor penetration for imaging.26 Antibody fragments such as the scFvs, owing to the lack of an Fc fragment, are showing great promise in the clinical arena with better pharmacokinetic profiles and potentially lower immunogenicity than the full length antibodies.26,51 Another advantage of using recombinant scFv for imaging and screening is its cost efficient large-scale production under GMP regulations for clinical/ pre-clinical safety and efficacy studies. For US imaging with Thy1-targeted MBs (MBThy1-scFv), we used a well-established transgenic mouse model that spontaneously develops pancreatic tumors resembling human PDAC.30 Pancreatic tumors in this mouse model overexpress Thy1 on the neovasculature as evaluated by tissue immunofluorescence staining.19,25

We reported several major improvements in the Thy1-scFv protein sequence, MB shell composition, and their conjugation strategies towards the development of a fully translatable contrast agent. First, the immunogenic biotin/streptavidin coupling used for conjugating Thy1-scFv onto the MBs is replaced with a physiologically amenable thiol-MA conjugation chemistry. We introduced a cysteine at the carboxy terminal end of the protein construct to enable site-specific bioconjugation of the scFv ligands to the MBs shell bearing maleimide (MA) functional groups. Thiol-reactive MA chemistry has already been used in several potent antibody-drug conjugate therapeutics for human use approved by FDA.52,53 In our in vitro analyses, the MA groups on the MBs enabled conjugations of scFv without changing MB size due to rapid gas dissipation or loss of shell stability and these MBs maintained their ability to bind to Thy1 target under liquid shear stress conditions in a parallel-plate flow chamber setup with endothelial cells grown on a slide. Micrometer-wide channels54 and 3D microvascular networks55 setups with physiologically relevant blood flow conditions and capillary microenvironment may be more useful in examining MB interaction with vascular endothelium in the presence of US. Future assessments of targeted-MB acoustic response in phantom experiments and in vivo half-life are also important because of possible changes in MB shell stiffness or viscosity with the addition of targeting ligands. The DPPC, DPPE, DPPE-PEG(5000) and DSPE-PEG(5000) based lipids used to form these neutral MBs are fully biocompatible for human use, have low degradation rate and long shelf life.37 These MB shell components are not known to cause toxicity, changes in heart rate and blood pressure. The removal of dipalmitoyl phosphatidic acid (DPPA) from the MB shell is an improvement, as DPPA is known to undergo hydrolysis and cause mild, self-limited back pain in some patients.37,56 The core of these MBs has an inert and heavy perfluorocarbon gas, which improves their stability and functionality in vivo due to limited gas diffusion through the lipid shell.57 While we conjugated the scFvs to the pre-formed MBs, this strategy can result in inconsistent scFv labeling efficiency across a polydisperse MB population, is time consuming to produce, and prone to batch variations for a consistent clinical imaging practice. For the future studies, we will perform bioconjugation of DSPE-PEG(5000)-MA to the scFv-(Glyc)5-Cys prior to admixing with other shell lipid components to formulate MBs with consistent scFv labels. This strategy will allow physicians to store a ready-to-use product and make targeted-MBs immediately before imaging sessions.58,59 Nonetheless, we observed highly specific Thy1 US molecular imaging signal enhancement in only the PDAC tissues but not the control tissues in vivo with MBThy1-scFv. Imaging signal was not stratified by tumor size groups in the current study due to the limited number of imaged tumors; however, the MBThy1-scFv can be used to image tumor foci as small as two millimeters in diameter by high frequency (21 MHz) US imaging in these animal models.25 More importantly, US molecular imaging with the MBThy1-scFv is capable of differentiating normal or L-arginine-induced pancreatic tissue from PDAC tumors, potentially allowing accurate and early detection of malignant tumors from benign lesions during the course of disease progression in high-risk individuals. Future studies in a larger number of animals are needed to assess the minimally detectable tumor size along with sensitivity and specificity of Thy1-targeted contrast MBs at lower frequencies (<6 MHz) that are often applied in transabdominal US imaging to scan the human pancreas. Towards this goal, the Thy1-scFv was further modified to remove the bacterial fusion protein sequence (TrxA) during its recombinant production, lowering any potential immunogenic effects in humans and further reducing its size (from ~44 kDa to 29 kDa) while maintaining its targeting activity. We confirmed that the scFv production can be scaled-up without losing its binding specificity against human Thy1 overexpressed on the cell-surface of a murine endothelial cells line, MS1Thy1, as well as the human PDAC tissue samples by immunostaining methods. The effective dose of scFv ligand required for contrast imaging and screening PDAC is relative to the varying endogenous tissue expressions of Thy1 in a patient’s tumor microenvironment; however, MB avidity predominantly dictates their binding to molecular targets in vivo as multiple ligands are conjugated on the surface of contrast agent. The tumor microenvironment expression of Thy1 highly correlated with the gene signature associated with pancreas-specific endothelial/ angiogenesis markers in our analysis of the human pancreatic cancer RNA-seq database.33 In agreement with the published literature on Thy1 protein expression in human PanINs and PDAC tissue samples,21,60,61 we observed high scFv immunofluorescence staining signals in the human PDAC-associated blood vessels and fibroblasts surrounding ductal structures. The varying Thy1 expression on the fibroblasts as well as the VEGFR2-positive vascular compartments indicate that the scFv-conjugated contrast MBs will be efficacious for human PDAC US molecular imaging. As pancreatic cancer is often hypovascular due to the dense surrounding parenchyma, validating angiogenic biomarker expression in suspected lesions by Thy1/VEGFR249,62 dual-targeting MBs will also be useful in the identification of PDAC based on high contrast US molecular imaging.33 Lastly, the pre-clinical destruction-replenishment technique used to quantify Thy1 molecular signal in our high frequency/ high resolution small animal US imaging system is not compatible with the low frequency real-time imaging techniques adopted in the clinical US scanners for human testing. Therefore, the MBThy1-scFv contrast agents must be applied to the clinical scanners and protocols employing novel algorithms that can increase the signal-to-noise ratio in contrast-mode images as well as discriminate between the molecular signal from the stationary targeted-MBs and non-specific circulating MBs without the application of high power destructive US pulse in the deep abdominal organs or having to use long delays post contrast administration to wait for clearance of circulating MBs from bloodstream.63,64

In conclusion, by modifying the scFv ligand and its conjugation chemistry to a clinically biocompatible MB contrast agent, we achieved significant improvements to the Thy1-targeted MBs for PDAC tumor imaging. These developments are promising in planning for the further clinical development of a Thy1-targeted contrast MB for the early and accurate diagnosis of human PDAC by US molecular imaging, thus elevating the overall patient survival of this deadly cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1.tiff

(A) Schematic representation of MB with Maleimide (MA) functional group and its conjugation to BODIPY FL L-Cystine dye under reducing conditions. (B) Confirmation of MB conjugation to BODIPY FL-L-Cystine dye with thiol-MA coupling reaction by flow cytometry.

Supplemental Digital Content 2.tiff

(A) Flow cytometry-based histograms confirming surface conjugation of biotinylated-scFv-(Gly)5-Cys to the MB shell with MA functional groups. (B) Size distribution and concentration analysis of Thy1-targeted and control MBs by particle size counter.

Supplemental Digital Content 3.tiff

SDS-PAGE analysis of scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 protein-dye conjugate by Coomassie stain (A) and fluorescence imaging (B).

Supplemental Digital Content 4.tiff

Flow cytometry histograms showing cell-surface Thy1 binding detection with scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 conjugate (100nM). Anti-Thy1-APC antibody (150 nM) is used as a positive control.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: ID, EJM, ERM and ECU are employed with NuvOx Pharma. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest. National Cancer Institute, Grant number: R41 CA203090 to NuvOx

REFERENCES

- 1.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the united states. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohno E, Hirooka Y, Kawashima H, et al. Natural history of pancreatic cystic lesions: A multicenter prospective observational study for evaluating the risk of pancreatic cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;33(1):320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oyama H, Tada M, Takagi K, et al. Long-term Risk of Malignancy in Branch-Duct Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):226–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu Y, Gentiluomo M, Lorenzo-Bermejo J, et al. Mendelian randomisation study of the effects of known and putative risk factors on pancreatic cancer. J. Med. Genet. 2020; doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106200. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young MR, Wagner PD, Ghosh S, et al. Validation of Biomarkers for Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer: Summary of the Alliance of Pancreatic Cancer Consortia for Biomarkers for Early Detection Workshop. Pancreas. 2018;47(2):135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandharipande PV, Heberle C, Dowling EC, et al. Targeted screening of individuals at high risk for pancreatic cancer: Results of a simulation model. Radiology. 2015;275(1):177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo W, Morris MC, Ahmad SA, et al. Screening patients at high risk for pancreatic cancer—Is it time for a paradigm shift? J. Surg. Oncol. 2019;120(5):851–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrikson NB, Aiello Bowles EJ, Blasi PR, et al. Screening for Pancreatic Cancer: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019;322(5):445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, et al. Frequent detection of pancreatic lesions in asymptomatic high-risk individuals: screening for early pancreatic neoplasia (CAPS 3 Study). Gastroenterology. 2012;142(4):796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coté GA, Smith J, Sherman S, et al. Technologies for imaging the normal and diseased pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(6):1262–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotopoulis S, Dimcevski G, Helge Gilja O, et al. Treatment of human pancreatic cancer using combined ultrasound, microbubbles, and gemcitabine: A clinical case study. Med. Phys. 2013;40(7):072902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korpanty G, Carbon JG, Grayburn PA, et al. Monitoring response to anticancer therapy by targeting microbubbles to tumor vasculature. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13(1):323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Săftoiu A, Vilmann P, Bhutani MS. The role of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Endosc. Ultrasound. 2016;5(6):368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dijkmans PA, Juffermans LJM, Musters RJP, et al. Microbubbles and ultrasound: From diagnosis to therapy. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2004;5(4):245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrara K, Pollard R, Borden M. Ultrasound Microbubble Contrast Agents: Fundamentals and Application to Gene and Drug Delivery. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2007;9(1):415–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Hossack JA, Klibanov AL. Targeting of microbubbles - contrast agents for ultrasound molecular imaging. J Drug Target. 2018;26(5–6):420–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Hagemeyer CE, Hohmann JD, et al. Novel single-chain antibody-targeted microbubbles for molecular ultrasound imaging of thrombosis: Validation of a unique noninvasive method for rapid and sensitive detection of thrombi and monitoring of success or failure of thrombolysis in mice. Circulation. 2012;125(25):3117–3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klibanov AL. Ligand-carrying gas-filled microbubbles: Ultrasound contrast agents for targeted molecular imaging. Bioconjug. Chem. 2005;16(1):9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foygel K, Wang H, MacHtaler S, et al. Detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice by ultrasound imaging of thymocyte differentiation antigen 1. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(4):885–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sauzay C, Voutetakis K, Chatziioannou A, et al. CD90/Thy-1, a Cancer-Associated Cell Surface Signaling Molecule. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;7:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu J, Thakolwiboon S, Liu X, et al. Overexpression of cd90 (thy-1) in pancreatic adenocarcinoma present in the tumor microenvironment. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue A, Tanaka J, Takahashi H, et al. Blood vessels expressing CD90 in human and rat brain tumors. Neuropathology. 2016;36(2):168–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schubert K, Gutknecht D, Köberle M, et al. Melanoma cells use thy-1 (CD90) on endothelial cells for metastasis formation. Am. J. Pathol. 2013;182(1):266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiore VF, Ju L, Chen Y, et al. Dynamic catch of a Thy-1-α5 β1 +syndecan-4 trimolecular complex. Nat. Commun. 2014; 5:4886 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abou-Elkacem L, Wang H, Chowdhury SM, et al. Thy1-targeted microbubbles for ultrasound molecular imaging of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24(7):1574–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.England CG, Hernandez R, Eddine SBZ, et al. Molecular Imaging of Pancreatic Cancer with Antibodies. Mol. Pharm. 2016;13(1):8–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unnikrishnan S, Du Z, Diakova GB, et al. Formation of Microbubbles for Targeted Ultrasound Contrast Imaging: Practical Translation Considerations. Langmuir. 2019;35(31):10034–10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinol M, Casalini P, Maggiolo M, et al. Biochemical modifications of avidin improve pharmacokinetics and biodistribution, and reduce immunogenicity. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;78(2):189–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravasco JMJM, Faustino H, Trindade A, et al. Bioconjugation with Maleimides: A Useful Tool for Chemical Biology. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2019;25(1):43–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aguirre AJ, Bardeesy N, Sinha M, et al. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2003;17(24):3112–3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kui B, Balla Z, Vasas B, et al. New insights into the methodology of L-arginine-induced acute pancreatitis. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawra R, Sharif R, Phillips P, et al. Development of a new mouse model of acute pancreatitis induced by administration of L-arginine. Am. J. Physiol. - Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007;292(4):1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katsuta E, Qi Q, Peng X, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinomas with mature blood vessels have better overall survival. Sci. Rep. 2019; 9(1):1310. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37909-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, et al. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W556–W560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borden MA, Song KH. Reverse engineering the ultrasound contrast agent. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;262:39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moccetti F, Weinkauf CC, Davidson BP, et al. Ultrasound Molecular Imaging of Atherosclerosis Using Small-Peptide Targeting Ligands Against Endothelial Markers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2018;44(6):1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unger EC, Evans DC. Phospholipid composition and microbubbles and emulsions formed using same. WO2015192093A1 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.True LD, Zhang H, Ye M, et al. CD90/THY1 is overexpressed in prostate cancer-associated fibroblasts and could serve as a cancer biomarker. Mod. Pathol. 2010;23(10):1346–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elyada E, Bolisetty M, Laise P, et al. Cross-species single-cell analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(8):1102–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chari ST, Kelly K, Hollingsworth MA, et al. Early Detection of Sporadic Pancreatic Cancer: Summative Review. Pancreas. 2015;44(5):693–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singhi AD, Koay EJ, Chari ST, et al. Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer: Opportunities and Challenges. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(7):2024–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dimcevski G, Kotopoulis S, Bjånes T, et al. A human clinical trial using ultrasound and microbubbles to enhance gemcitabine treatment of inoperable pancreatic cancer. J. Control. Release. 2016;243:172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burkhardt C, Tzschätzsch H, Schmuck R, et al. Ultrasound Time-Harmonic Elastography of the Pancreas: : Reference Values and Clinical Feasibility. Invest. Radiol. 2020;55(5):270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Payen T, Oberstein PE, Saharkhiz N, et al. Harmonic motion imaging of pancreatic tumor stiffness indicates disease state and treatment response. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26(6):1297–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anvari A, Forsberg F, Samir AE. A primer on the physical principles of tissue harmonic imaging. Radiographics. 2015;35(7):1955–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kitano M, Kudo M, Yamao K, et al. Characterization of small solid tumors in the pancreas: The value of contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012;107(2):303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dietrich CF, Jenssen C. Modern ultrasound imaging of pancreatic tumors. Ultrasonography. 2020;39(2):105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laeseke PF, Chen R, Jeffrey RB, et al. Combining in vitro diagnostics with in vivo imaging for earlier detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Challenges and solutions. Radiology. 2015;277(3):644–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pysz MA, Machtaler SB, Seeley ES, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2-targeted contrast-enhanced us of pancreatic cancer neovasculature in a genetically engineered mouse model: Potential for earlier detection. Radiology. 2015;274(3):790–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smeenge M, Tranquart F, Mannaerts CK, et al. First-in-human ultrasound molecular imaging with a VEGFR2-specific ultrasound molecular contrast agent (BR55) in prostate cancer a safety and feasibility pilot study. Invest. Radiol. 2017;52(7):419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strohl WR. Current progress in innovative engineered antibodies. Protein Cell. 2018;9(1):86–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen BQ, Xu K, Liu L, et al. Conjugation site modulates the in vivo stability and therapeutic activity of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30(2):184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sochaj AM, Świderska KW, Otlewski J. Current methods for the synthesis of homogeneous antibody-drug conjugates. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015;33(6):775–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shamout FE, Pouliopoulos AN, Lee P, et al. Enhancement of Non-Invasive Trans-Membrane Drug Delivery Using Ultrasound and Microbubbles During Physiologically Relevant Flow. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2015;41(9):2435–2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Juang EK, De Cock I, Keravnou C, et al. Engineered 3D Microvascular Networks for the Study of Ultrasound-Microbubble-Mediated Drug Delivery. Langmuir. 2019;35(31):10128–10138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Appis AW, Tracy MJ, Feinstein SB. Update on the safety and efficacy of commercial ultrasound contrast agents in cardiac applications. Echo Res. Pract. 2015;2(2):R55–R62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee H, Kim H, Han H, et al. Microbubbles used for contrast enhanced ultrasound and theragnosis: a review of principles to applications. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2017;7(2):59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pochon S, Tardy I, Bussat P, et al. BR55: A lipopeptide-based VEGFR2-targeted ultrasound contrast agent for molecular imaging of angiogenesis. Invest. Radiol. 2010;45(2):89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Myrset AH, Fjerdingstad HB, Bendiksen R, et al. Design and characterization of targeted ultrasound microbubbles for diagnostic use. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2011;37(1):136–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pei X, Zhu J, Yang R, et al. CD90 and CD24 Co-Expression is associated with pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi J, Lu P, Shen W, et al. CD90 highly expressed population harbors a stemness signature and creates an immunosuppressive niche in pancreatic cancer. 2019:158–169. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Anderson CR, Rychak JJ, Backer M, et al. ScVEGF microbubble ultrasound contrast agents: A novel probe for ultrasound molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis. Invest. Radiol. 2010;45(10):579–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hyun D, Abou-elkacem L, Bam R, et al. Nondestructive Detection of Targeted Microbubbles Using Dual-Mode Data and Deep Learning for Real-Time Ultrasound Molecular Imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2020; doi: 10.1109/TMI.2020.2986762 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kondo S, Takagi K, Nishida M, et al. Computer-Aided Diagnosis of Focal Liver Lesions Using Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography with Perflubutane Microbubbles. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2017;36(7):1427–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1.tiff

(A) Schematic representation of MB with Maleimide (MA) functional group and its conjugation to BODIPY FL L-Cystine dye under reducing conditions. (B) Confirmation of MB conjugation to BODIPY FL-L-Cystine dye with thiol-MA coupling reaction by flow cytometry.

Supplemental Digital Content 2.tiff

(A) Flow cytometry-based histograms confirming surface conjugation of biotinylated-scFv-(Gly)5-Cys to the MB shell with MA functional groups. (B) Size distribution and concentration analysis of Thy1-targeted and control MBs by particle size counter.

Supplemental Digital Content 3.tiff

SDS-PAGE analysis of scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 protein-dye conjugate by Coomassie stain (A) and fluorescence imaging (B).

Supplemental Digital Content 4.tiff

Flow cytometry histograms showing cell-surface Thy1 binding detection with scFv-(Gly)5-Cys-AlexaFluor-647 conjugate (100nM). Anti-Thy1-APC antibody (150 nM) is used as a positive control.