Abstract

Cells are continuously subject to various stresses, battling both exogenous insults as well as toxic byproducts of normal cellular metabolism and nutrient deprivation. Throughout the millennia, cells developed a core set of general stress responses that promote survival and reproduction under adverse circumstances. Past and current research efforts have been devoted to understanding how cells sense stressors and how that input is deciphered and transduced, resulting in stimulation of stress management pathways. A prime element of cellular stress responses is the increased transcription and translation of proteins specialized in managing and mitigating distinct types of stress. In this review, we focus on recent developments in our understanding of cellular sensing of proteotoxic stressors that impact protein synthesis, folding, and maturation provided by the model eukaryote the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, with reference to similarities and differences with other model organisms and humans.

Keywords: stress sensing, heat shock, proteostasis, oxidative stress, yeast, human

1. Introduction

Under periods of physicochemical stress, including but not limited to high heat, oxidative stress, extreme pH, severe osmotic imbalance, or nutrient deprivation, proteins are subject to misfolding, especially nascent proteins that have not yet become fully stabilized by intra-protein interactions. To combat the deleterious effects of such stresses and the abundance of misfolded polypeptides that ensue, cells undergo multiple physiological adaptations, including translational arrest, cell cycle arrest, and immediate activation of a series of transcriptional response programs that produce an array of cytoprotective proteins. In this review, we examine recent advances in understanding how proteotoxic stress in the nucleus/cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria, as well as proteotoxic oxidative stress, is sensed and transduced to activate dedicated gene expression responses.

2. Sensing and response to proteotoxic stress in the cytoplasm

The subject of how elevated temperature that challenges folding of nascent protein chains emerging from the ribosomal exit tunnel is sensed by cells and how that signal is transduced into a response has been an ongoing area of research for some time. This “heat shock response” (HSR) in yeast and other organisms scales with the severity of temperature exposure. Shift to elevated temperature (37°C–42°C for yeast) sustains the transcriptional response for an extended time, changing expression of over 3,000 genes [1,2]. The transcription factor HSF1 (Hsf1 in yeast) is generally recognized as the master regulator of the HSR in eukaryotes. Hsf1 is recruited to promoters of genes comprising the HSR regulon by binding at genome sequences termed heat shock elements (HSEs) (reviewed in [3]). Pincus and collaborators recently mapped genome binding sites for Hsf1 in yeast, determining a total of 74 sites, 69 of which are bound under heat shock (HS). In non-stress conditions, Hsf1 basally binds 43 loci, but under stress, Hsf1 cooperates with chromatin remodeling complexes to reveal HSEs occluded by nucleosomes [4]. The relatively small number of binding sites directly bound by Hsf1 determined in this recent study, compared to the larger number of genes generally affected by general heat shock, may be due to separate downstream factors initiated by Hsf1, but individually distributing and amplifying the HSR activation signal into branching pathways. Additionally, other transcription factors in yeast are responsible for increases in expression of a significant number of stress-induced genes, such as Yap1 responding to oxidative stress and Msn2/4 as a general stress responder [3]. The structure of Hsf1 itself is dynamic and thermosensitive. Hsf1 is composed of several conserved structural elements, consisting of a DNA-binding domain, a leucine zipper motif domain required for trimerization, a serine-rich regulatory domain, and transcriptional activation domains at both the N- and C-termini. At elevated temperature, the regulatory domain unfolds while the trimerization domain zips together [5]. To attenuate the HSR signal, re-monomerization is managed by the entropic pulling action of chaperone cofactors [6]. Variability in Hsf1 potency, and thus the extent of activation of its downstream targets, is linked to the level of phosphorylation. While not necessary for basal activation, increasing levels of phosphorylation act in a non-specific manner to positively tune the intensity or “gain” of HSR activation by Hsf1 [7]. Fluctuation in the degree of Hsf1 phosphorylation was recently shown not to be uniform cell-to-cell but instead provides plasticity in the HSR that appears to be beneficial at the population level. In a micro-Darwinian scenario, each cell’s response varies and provides Hsp90-mediated adaptability that increases the likelihood of survival [8]. Several other mechanisms of Hsf1 post-translational modifications that impact activation, duration, and magnitude of the HSR also exist in higher eukaryotes, including acetylation and sumoylation [9,10].

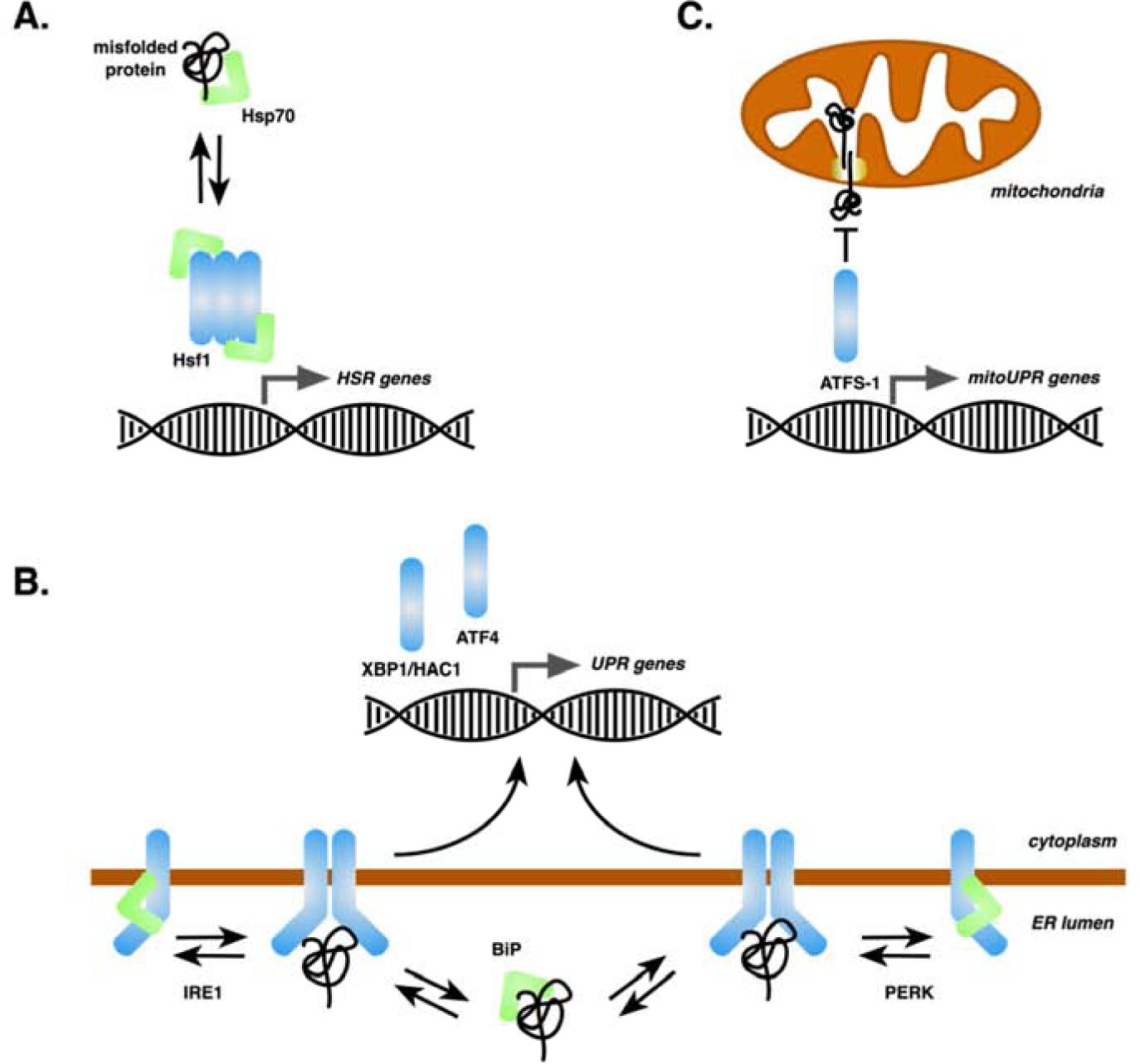

Interaction between Hsf1 and select protein chaperones was long thought to be a key tenet of HSR regulation, although compelling data to bolster this model were a long time coming [11]. Decreased Hsf1 activity results in a significant decrease in expression of key chaperones, including Hsp70 and Hsp90, resulting in global cytotoxicity associated with protein aggregation [12]. The relationship between Hsp70 and Hsf1 has been thoroughly examined of late, as Hsp70 emerges to play a key role as a stress sensor for Hsf1. Hsp70 recognizes hydrophobic patches in polypeptides, which are typically only exposed in intrinsically disordered proteins or when a protein has been misfolded or damaged. Hsp70 was only recently found to specifically recognize both the previously defined transcriptional regulatory CE2 (conserved element 2) site in the Hsf1 C-terminal transcriptional activation domain and a newly identified site within the N-terminal activation domain, dually suppressing Hsf1’s ability to activate gene expression and thus the HSR (Fig. 1A) [13,14]. Under heat shock conditions, newly synthesized proteins are highly susceptible to damage by misfolding; indeed, misfolded proteins were demonstrated to titrate cytosolic/nuclear Hsp70 (Ssa1 in yeast) from Hsf1, thereby activating the HSR [7]. Hsp70 was shown to decrease association with Hsf1 by 77% under elevated temperature, and by nearly 100% when exposed to the proline analog compound azetidine 2-carboxylic acid (AZC) [15]. It thus appears that the prominent protein chaperone Hsp70 plays a direct feedback inhibitory role in its own production as well as governing a significant percentage of the stress-induction of the proteostasis network.

Fig. 1: Misfolded proteins as a proximal signal for proteotoxic stress responses.

A, The Hsf1 trimer in yeast is held in a transcriptionally repressed state by Hsp70 chaperones that are titrated in the presence of misfolded cytoplasmic/nuclear proteins, resulting in activation of the Hsf1-mediated component of the HSR. B, The IRE1 and PERK sensor proteins oscillate between monomer and dimer/oligomeric states, the latter of which are stabilized by binding of misfolded proteins to a lumenal binding pocket. Active dimers promote downstream events resulting in transcription of UPR genes by the XBP1/Hac1 or ATF4 transcription factors. Hsp70 chaperones both titrate abundance of free misfolded proteins and exist in a repressive complex with IRE1 or PERK. C, Accumulation of misfolded proteins within the mitochondrial matrix or complexed with the import machinery slows targeting of the ATFS-1 transcription factor long enough to allow its nuclear translocation and activation of UPRmt genes.

As an added layer of regulation, Hsp70 is subject to several types of post-translational modifications that alter its activity and thereby affect control of the HSR through Hsf1. AMPylation, found in higher eukaryotes but not yeast, was introduced into S. cerevisiae and shown to induce a strong cytoplasmic Hsf1-mediated HSR, similar to outcomes observed in humans and worms [16]. AMPylation was shown to reduce the ATPase functionality of cytoplasmic Hsp70 and resulted in an interesting and unexplained scenario where an increase in aggregation of α-synuclein and Aβ was documented, but without the usually associated cytotoxicity [17]. Deacetylation of four lysine residues within Hsp70 was also shown to occur under heat shock conditions, altering the interactome of Hsp70, activating Hsf1, and enhancing cellular thermotolerance [18]. In human HeLa cells, Hsp70 was shown to be glutathionylated on multiple cysteines, perturbing a key structural domain and resulting in diminished contact with the substrate [19]. Our lab and others have previously shown that alkylation or genetic oxidomimetic substitution of key conserved cysteine residues within Hsp70 activates Hsf1 [20,21]. In addition to the direct effects these modifications may have on Hsp70-dependent biology, a secondary effect on the Hsp70-Hsf1 regulatory circuit provides yet another layer of HSR control.

Recent advances have been made understanding HSR regulatory pathways outside of the canonical chaperone mechanism. As a crucial component of the translation process, tRNAs are a key factor in protein biogenesis. tRNA supply can be modified both pre- and post-synthesis to selectively manage the synthesis of specific proteins. Stress response genes are enriched in codons for rare tRNAs, meaning that under basal conditions, the production of proteins encoded by these genes is limited. Through an unknown sensing mechanism, cells increase the abundance of these rare tRNAs under stress conditions, allowing for increased synthesis of rare tRNA-containing genes [22]. Existing tRNAs can also be modified, such as by thiolation. Cells deficient in a tRNA-thiolation pathway showed a constitutively activated HSR, while HS in a wild type cell showed decreased levels of thiolated tRNA compared to basal levels [23]. This relationship may confer stress protection by decreasing translation, as tRNA thiolation is a contributing factor in the control of protein synthesis. Gene expression can also be modulated spatially by the three-dimensional organization of chromatin, changing the accessibility of genes to be bound by their co-factors. Heat shock protein genes were seen to coalesce into foci under heat stress, forming closely apposed regions of high transcription activity [24]. Interestingly, the dynamic reorganization is transcription factor-selective, as genes associated with Hsf1 coalesced and interacted under thermal stress, while constitutively active genes and genes under the control of another stress transcription factor, Msn2, did not [25]. The Hsf1-based HSR is thus uniquely responsive to multiple control modalities that sense changes in cellular properties ranging from translational potency, the folding status of the proteome, physiological perturbations in temperature, and redox state, and even genome architecture.

3. Sensing and response to proteotoxic stress in the endoplasmic reticulum

In humans, approximately one-third of the cellular proteome, particularly transmembrane and secreted proteins, are folded and assembled in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The ER performs a diversity of essential cellular functions in addition to protein biogenesis, including regulated calcium storage and release, lipid biosynthesis, and trafficking, and membrane biogenesis. Due to its importance, the maintenance of homeostasis in the ER is fundamental for the survival of any eukaryotic cell, and perturbations of ER homeostasis such as nutrient starvation, proteotoxic stress, and redox imbalance can lead to the accumulation of misfolded proteins within the ER lumen. ER stress triggers activation of a highly conserved adaptive response referred to as the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR is composed of multiple signaling pathways leading to induction of an array of cytoprotective proteins whose main role is to restore ER proteostasis and membrane integrity. In higher eukaryotes, failure of cells to return to homeostasis or prolonged stress exposure prompts induction of the apoptosis cell death program through the same pathways [26]. Although the UPR is conserved in metazoans, yeast possess only one ER transmembrane sensor protein, inositol requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) whereas humans, in addition to IRE1, possess two independent UPR pathways mediated by protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6)(reviewed in [27]).

IRE1 (yeast Ire1) is a type I transmembrane protein, with the lumenal portion at its amino-terminus and the carboxyl-terminal half localized in the cytosol. The amino-terminal domain is comprised of five sub-regions (named I through V), where regions II through IV form a tightly folded domain that is responsible for dimer/oligomer formation and is fundamental for stress-sensing [28]. The cytosolic domain contains both protein serine/threonine kinase and endoribonuclease (RNase) activities. Two IRE1 isoforms, IRE1α and IRE1β, are found in the mammalian genome, with IRE1α being expressed ubiquitously while IRE1β is solely found in intestinal and lung epithelium [27]. Three different modes of stress sensing by IRE1 have been described: the “direct association” model, “BiP (ER Hsp70 chaperone) competition” and more recently the alternative “BiP allosteric” model. The direct association model postulates that misfolded proteins bind directly to the lumenal domain (LD) of IRE1 to activate UPR signaling [29]. In this model, the association of misfolded protein mediates conformational changes that result in the oligomerization of the IRE1 LD and subsequent activation of UPR signaling [30]. BiP does not play a role in sensing ER stress but is involved in binding and sequestering inactive monomeric IRE1 [31]. In the competition model, BiP acts as a repressor of the UPR by binding the IRE1 LD via its substrate-binding domain to prevent dimerization of IRE1 in a repressive complex that is released upon titration of BiP by misfolded ER proteins [32,33]. In this model BiP nucleotide exchange factors (NEF) play a role by facilitating the exchange of ADP to ATP, causing BiP to dissociate from IRE1 LD [34]. Finally, a recently proposed “allosteric model” stipulates an interaction between the BiP ATPase domain and the IRE1 LD [35]. In this model, the interaction is independent of ER NEFs and is distinct from the chaperone-substrate type interaction that occurs via the BiP SBD [33]. Misfolded proteins bind exclusively to the BiP SBD, which acts as a direct sensor of ER stress and leads to dissociation of the BiP ATPase domain from the IRE1 LD via a conformational change activating UPR signaling [36]. As misfolded proteins and IRE1 LD bind to different domains of BiP, there is no direct competition. In all three scenarios, after the detection of misfolded proteins, the signal is propagated across the ER membrane and IRE1 is activated through dimerization/oligomerization and trans-autophosphorylation, resulting in allosteric activation of its carboxyl-terminal RNase domain (Fig. 1B) [28]. Activation of RNase activity catalyzes the unconventional splicing of the HAC1 (in yeast) or XBP1 (in humans) mRNAs [37,38]. Spliced (activated) HAC1 upregulates nearly 400 target genes in yeast (reviewed in [39]). An alternative method of activating HAC1 has recently been described in yeast and worms. According to this new model, there are two forms of transcription of the ORF Hac1. The first, classic form, consists of the transcription of the proximal TSS (transcription start site) which produces a canonical transcript that is translated into the protein while the second, alternative form, consists of the activation of the distal TSS resulting in the synthesis of a 5’ extended transcript that encodes the ORF but does not lead to ORF expression because of translation of upstream ORFs (uORFs) in the extended 5’ leader. Transcription from the distal TSS also represses the use of the proximal TSS in cis by transcriptional interference [40]. This mechanism allows HAC1 to act either directly as a transcription factor or indirectly as a translational repressor for LUTI (long undecoded transcript isoform) targets. This mechanism represents an important but not yet fully integrated advance in our understanding of UPR activation.

In addition to Ire1 sensing the lumenal burden of misfolded proteins, there appears to be an additional intimate relationship between the redox state of the cell, respiration, and activation of the Ire1 arm of the UPR in yeast. Kritsiligkou and colleagues suggest that the production of ROS from the constitutive activation of UPR is responsible for most of the phenotypes observed in yeast strains lacking cytosolic thioredoxin reductase (TRR1), such as slow growth, shortened longevity, and oxidation of the cytoplasmic glutathione (GSH) pool [41]. In this study, disruption of UPR activation through the deletion of either HAC1 or IRE1 reversed the phenotypes of trr1Δ mutant strains. Nevertheless, it was recently reported that UPR activation through the IRE1-Hac1 mechanism can be transiently induced upon diauxic shift in a mechanism dissociated from traditional activation through misfolded proteins, with ROS possibly serving as mediators for UPR induction. In this model, ROS resulting from aerobic respiration appear to activate IRE1 through directly or indirectly acting on its cytosolic or transmembrane domain [42].

PERK is an ER transmembrane kinase found in metazoans. Although PERK and IRE1 share low homology, PERK’s mechanism of action is similar to IRE1 [43]. Like IRE1, PERK is also a transmembrane protein with an amino-terminal domain in the ER and a carboxyl-terminal domain in the cytosol. The N-terminal domain of PERK is bound by the Hsp70 GRP78/BiP, but an overload of misfolded proteins in the ER stimulates dimerization and cross-phosphorylation of PERK, causing it to no longer associate with the chaperone (Fig. 1B). Activation of PERK leads to phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-α (eIF2α) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)[43]. eIF2α phosphorylation results in temporary attenuation of overall protein translation and up-regulation of ATF4 (activation transcription factor 4) while ATF6 (activation transcription factor 6; see below) is packaged into vesicles and transported to the Golgi apparatus [44]. ATF4 in turn up-regulates CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein) and GADD34 (growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible protein), among other targets [45]. CHOP promotes ER stress-induced apoptosis while GADD34 is involved in a negative feedback loop to counteract PERK by dephosphorylation of eIF2α, which resumes protein synthesis and further sensitizes cells to apoptosis [46]. As a third arm of the UPR, the lumenal and transmembrane domains of the transcriptional activator ATF6 are cleaved by Golgi-localized site-1 and site-2 proteases (S1P and S2P) under stress conditions. This processing event liberates an N-terminal cytosolic fragment containing a basic leucine zipper transcription factor domain, ATF6 (N), for localization into the nucleus activating the transcription of ER chaperones, lipid biosynthesis, and ER-associated degradation proteins [47]. Recently, Wang and colleagues [48] showed that mammalian PERK can directly interact with misfolded proteins through a region of its lumenal domain, with PERK acting similarly to several canonical chaperones by binding exposed hydrophobic regions of misfolded proteins and initiating its dimerization and subsequent activation, in a manner conceptually similar to Ire1.

4. Sensing and response to proteotoxic stress in mitochondria

Although the UPR has been well characterized in the context of the ER, a similar stress response pathway also exists for mitochondria (UPRmt). Despite mitochondria possessing their own DNA, most of the mitochondrial proteome consists of nuclear-encoded proteins synthesized in the cytoplasm that must be imported and processed. Delay or failure in processing of the precursor proteins triggers the activation of UPRmt, with the consequent recruitment of mitochondrial-resident chaperone machinery [49,50]. The signaling pathway controlling the UPRmt has been best elucidated in C. elegans, where the transcription factor ATFS-1 (activation transcription factor 1) is highly sensitive to defects in mitochondrial import efficiency (Fig. 1C) [51]. ATFS-1 contains both mitochondrial and nuclear localization sequences and therefore is uniquely poised to communicate mitochondrial stress to the nucleus. Under normal conditions, the nascent ATFS-1 protein is routed to the mitochondrial import machinery where it is rapidly degraded by the LonP protease in the mitochondrial matrix [51]. However, during mitochondrial stress, protein import is compromised causing the ATFS-1 protein to accumulate in the cytoplasm, allowing its C-terminal nuclear localization sequence to access the nuclear import machinery. Once in the nucleus, ATFS-1 activates the transcription of genes to restore mitochondrial health such as chaperones, protein import machinery, ROS detoxification genes, and glycolysis factors to restore mitochondrial and cellular health [52]. Studies suggest that additional pathways comprise the UPRmt as among the 700 transcripts found to be induced during mitochondrial stress in C. elegans, only ~400 require ATFS-1 for induction [51]. Mitochondrial stress appears to intersect with the canonical HSR in the worm as well. The HSR is repressed in C. elegans with aging but low levels of mitochondrial-specific stress were found to reverse this effect without affecting reproductive capacity (fecundity). Importantly, both the intact HSR and an increased healthspan required HSF-1, demonstrating both communication between these two pathways (UPRmt and the HSR) and the importance of maintaining proteostasis during aging [53]. A mammalian ortholog of ATFS-1, ATF5, has been shown to regulate the UPRmt in mammalian cells and to up-regulate quality control genes in response to mitochondrial stress [54]. In addition to ATF5, CHOP, and CEBPB (C/EBPβ) are additional transcription factors involved in the mammalian UPRmt [55]. Recent work suggests that the nuclear transcription factor Rox1 senses emergent defects in mitochondrial pre-sequence processing and is itself imported into mitochondria bypassing most of the import machinery, where it then binds mitoDNA and performs a TFAM-like (mitochondrial transcription factor A) function pivotal for transcription and translation to escape apoptosis and restore organellar proteostasis and import capacity [50]. Mitochondrial proteotoxic stress is a common occurrence in some types of cancer, cardiac and neurodegenerative diseases, underscoring the importance of a thorough understanding of the UPRmt in human cells [56–58]. Interestingly, yeast lacks an ATFS-1 homolog or analogous response system. However, a related UPR activated by mistargeting of mitochondrial proteins (UPRam) has been described that involves activation of the proteasome to degrade accumulated mitochondrial precursor proteins [59].

5. Sensing and transcriptional response to proteotoxic oxidative stress

Due to both endogenous processes and exogenous compounds, all organisms are exposed to reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS are generated by the partial reduction of oxygen and can lead to formation of highly reactive molecules such as hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals. Despite being a common by-product of metabolic processes, ROS can cause extensive damage to several cellular components, such as lipids, proteins, and DNA [60]. The likely primary source of endogenous ROS is via leakage of electrons from the respiratory chain in the mitochondria during the production of ATP by oxidative phosphorylation [61]. Exposure to elevated levels of these harmful compounds can overload the redox management network that cells use to maintain ROS at a tolerable threshold, and this imbalance activates an elaborate response network called the oxidative stress response (OSR), upregulating proteins that mitigate the stress via detoxification and/or increased resistance. The inefficiency or inability of the cellular machinery to neutralize ROS compounds is intimately associated with the development of several diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases, along with being heavily intertwined with the cellular aging process [60]. Current research trends are focused on processes by which cells sense an imbalance in the redox environment and respond accordingly through selective changes in transcription and translation. As an example, genes classified by their involvement in ‘ATPase function’, ‘proteasome’, and especially ‘oxidation-reduction process’ are significantly over-represented under heavy oxidative stress in yeast, from a pool of over 300 genes that are transcriptionally altered [62].

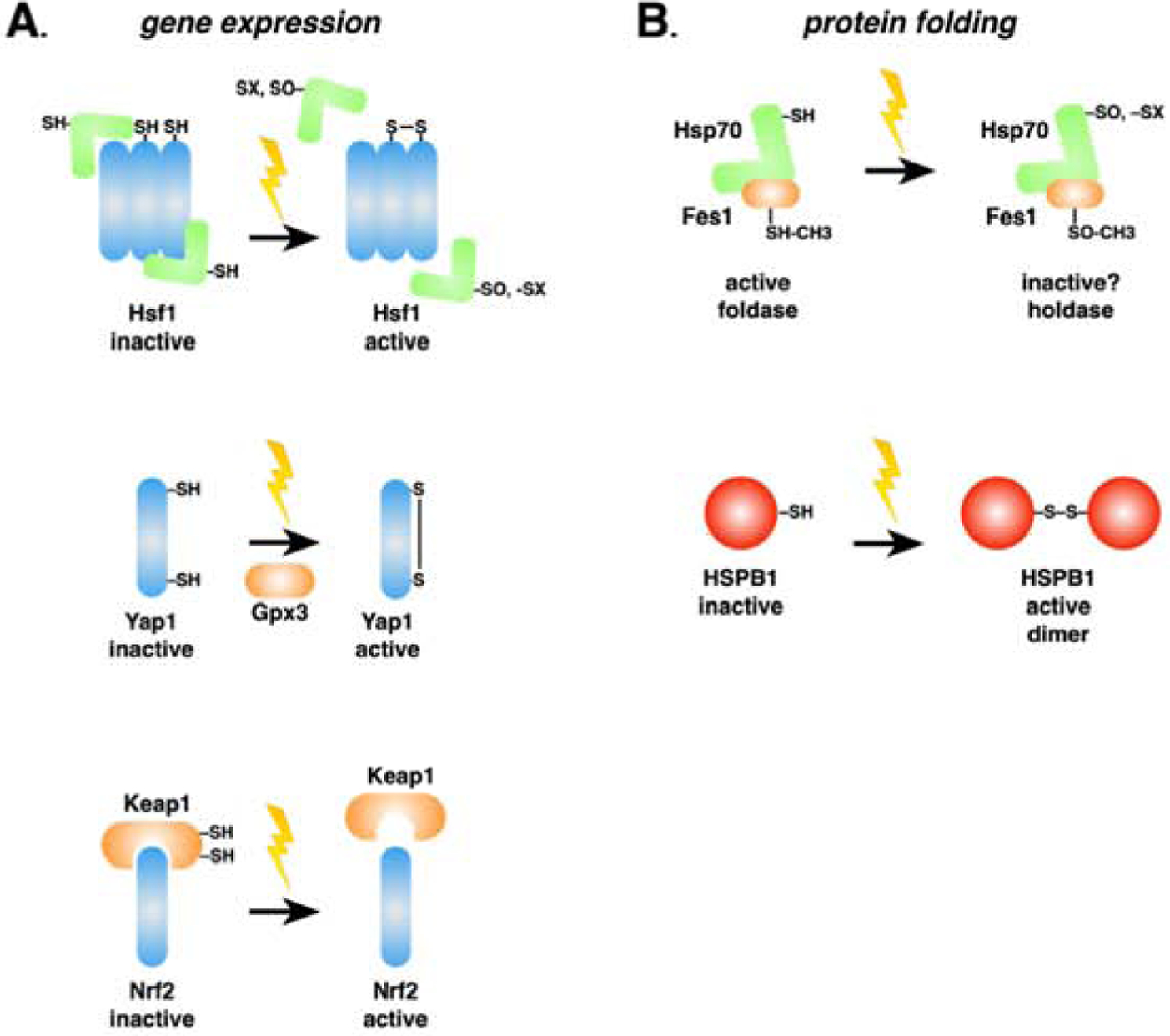

Many ROS-specific regulatory mechanisms are based on the oxidation state of protein cysteine residues, in part due to the multiple oxidation states that cysteine can maintain, general reversibility, and ease of reactivity, making this residue a versatile redox sensor [63,64]. For example, in yeast cells experiencing hydrogen peroxide stress, cysteines in the glutathione peroxidase Gpx3 form a disulfide bridge with a cysteine of Yap1, the major positive regulator of the OSR (Fig. 2A) [65]. Yap1 contains two distinct cysteine-rich domains that differentially sense oxidants to confer varying responses to stresses, such as inducing TRX2 transcription in response to H2O2, versus the thiol oxidant diamide as well as other thiol-chelating stressors such as heavy metals [66]. In both scenarios, activated Yap1 translocates from the cytoplasm into the nucleus to activate expression of antioxidant genes. An analogous OSR transcriptional circuit in mammalian cells is based on the transcription factor nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2 (Nrf2). Nrf2 is regulated primarily by interaction with Kelch-like ECH-associated protein (KEAP1) that both retains the transcription factor in the cytoplasm and promotes its rapid degradation (Fig. 2A; summarized in [67]). KEAP1 is a cysteine-rich protein and multiple cysteine residues have been documented to act as sensors for oxidants and thiol-reactive electrophiles [68]. Cysteine modification ultimately results in inability to complex with Nrf2, promoting the latter’s DNA binding and activation of an array of antioxidant genes that in humans play important roles in inflammation, chronic disease, and detoxification [69]. Msn2/4, another key positive regulator of the OSR in yeast, is indirectly dependent on the thiol status of a zinc-coordinating cysteine residue in the thioredoxin Trx2. Oxidation of this cysteine results in a conformational change and zinc release which mediates localization of the transcription factor Msn2/4 to the nucleus through an unknown mechanism [70,71]. Hsf1 also responds to redox imbalance and ROS via Hsp70 in yeast and directly through reactive cysteine residues as demonstrated in mouse [20,72,73]. In sum a common theme is clear – ROS and other thiol-reactive molecules are sensed by multiple regulators of gene expression via protein thiols to enable rapid and specific transcription of antioxidant defense proteins. However, the sensors need not be proximal as chaperones or dedicated accessory proteins can fulfill this role to transduce the activation signal.

Fig. 2: Proteotoxic oxidative stress sensing through reactive protein thiols.

Reactive oxygen species, xenobiotics, electrophiles and heavy metals (indicated by the lightning bolts) cause protein misfolding, generating stress signals as described in Fig. 1. Additionally, cytoprotective responses against these insults are induced at the levels of gene expression (A, left) and protein folding (B, right). A. Transcriptional oxidative stress response pathways in yeast (Yap1), humans (Nrf2), or both (Hsf1) are activated via different mechanisms that share a common theme of reactive cysteines in partner proteins sensing ROS and initiating functional changes in transcription factor activity. Of note, human HSF1 possesses reactive cysteines and is capable of directly sensing ROS, while yeast Hsf1 does not and relies on Hsp70 as indicated. B. As described in the text and as demonstrated in the case of Hsf1 regulation by Hsp70, protein chaperones are being revealed to directly sense ROS through similar means utilizing either cysteine or methionine residues. Although many questions remain unanswered, a trend of stabilizing the passive “holdase” function of chaperones is emerging, perhaps indicative of a survival strategy based on preventing further proteotoxic stress during ROS exposure and delaying refolding and repair until the danger passe

6. Chaperones as sensors of proteotoxic oxidative stress

Several chaperone proteins responsible for maintaining proteostasis are directly influenced by the redox environment. Bacterial and yeast cytosolic Hsp70 chaperones are heavily impacted by oxidation or adduction of several conserved thiols [74–76]. Within the ER, a normally oxidizing environment, the Hsp70 BiP (Kar2 in yeast) is modified on cysteine residues based on the thiol redox state to shift from a “folding” to a “holding” chaperone (Fig. 2B) [77]. As stated earlier, the yeast Ssa1 cytosolic Hsp70 is modified on at least two cysteines in the NBD, and we are currently investigating how cysteine alkylation or oxidation impacts global Hsp70 function in a stressed environment (Santiago and Morano, unpublished results). Fes1, an Ssa1 co-chaperone, was additionally shown to have altered function regulated by methionine oxidation (Fig. 2B) [78]. The yeast peroxiredoxin Tsa1 was also shown to alter behavior under redox stress, wherein hyper-oxidation of Tsa1 was a necessary component for recruitment of Hsp70 and Hsp104 to redox-damaged and aggregated proteins during aging [63]. In humans, sHsps play an important role in sensing ROS. HspB1 (or HSP27), HspB5, HspB6, and HspB8 are known to be upregulated in response to oxidative stress and hyperosmotic stress in rat hippocampal neurons [79]. HSPB1 acts as a redox-sensitive molecular chaperone through the residue Cys137. It has been proposed that Cys137 in HSPB1 modulates protein function by existing in either its oxidized (disulfide) or reduced (thiol) form (Fig. 2B) [80]. Although HspB1 is present in the cell as a monomer, dimer, or oligomer, it appears that HspB1 is most active as a chaperone in its dimeric form and that mutations in the intrinsically disordered region are linked with neuropathies [81]. We have found that two yeast sHSPs that function as misfolded protein “sequestrases” mobilize into stable compartments in yeast cells defective in redox balance due to deletion of the gene encoding thioredoxin reductase (trr1Δ), suggesting that redox and proteostatic balance are deeply interconnected (Goncalves and Morano, unpublished results).

Some un-liganded metal ions can be harmful due in part to their propensity to bind to free thiols as well as protein cysteine thiols, and the so-called soft metals or metalloids such as cadmium, arsenic, and chromium are highly toxic even at low micromolar concentrations and are potent inducers of the OSR [82–84]. Our laboratory recently showed that in experiments with yeast, cadmium induces aggregation of newly synthesized triose phosphate isomerase (Tpi1) in both yeast and human cancer cells and activates Hsp70-based recognition and sequestration of misfolded proteins [85]. Cadmium was also shown to impair protein folding in the ER, with subsequent induction of the UPR [86]. The presence of toxic metals can also be sensed by intermediate signal transducers as recently demonstrated for arsenic activating the transcription factor Yap8 via coordination with thiols in the MAP kinase Hog1 [87]. Together, these results demonstrate that in addition to significant changes in gene expression of antioxidant defense proteins, various forms of redox stress are sensed directly by the main defense proteins themselves for quick-acting responses to mitigate cellular damage. How cells sense and deal with oxidative stress extends beyond maintenance of the redox state of a single cell and may also be governed at the population level. A recent study observed a bi-modal distribution of oxidation state even within a population of yeast cells of the same age [88]. The transition from reduced to oxidized status could be a threshold-based phenomenon that leads to the emergence of at least two distinct cell subpopulations with different growth and survival potential in the face of chronic redox imbalance.

6. Conclusions

The ability to perceive and respond appropriately to the different insults in the environment are ongoing challenges for any living organism. Yeast and mammalian cells, despite existing in drastically different environments, share conserved mechanisms that regulate ancient gene expression programs such as the HSR, ER, and UPRmt and OSR. Cells can modulate their response by insult type, cellular compartment, magnitude of response, and a host of other factors. The balance of an adequate response without causing additional damage is a delicate measure of signals and components, and the imbalance of these functions is directly related to the development of various diseases in humans. Although our knowledge has advanced considerably in understanding the individual functioning of the different stress response activation programs, the current challenge of understanding crosstalk among these different programs remains. Of even greater interest is the real possibility of exploiting this information in the near future for therapeutic gain to combat diseases of protein misfolding.

Acknowledgments:

The authors apologize for citations of previous work omitted due to space constraints. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes for Health, GM127287.

Abbreviations:

- HSR

heat shock response

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- UPRmt

mitochondrial unfolded protein response

- OSR

oxidative stress response

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- [1].Mühlhofer M, Berchtold E, Stratil CG, Csaba G, Kunold E, Bach NC, Sieber SA, Haslbeck M, Zimmer R, Buchner J, The Heat Shock Response in Yeast Maintains Protein Homeostasis by Chaperoning and Replenishing Proteins, Cell Rep. 29 (2019) 4593–4607.e8. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hahn J-S, Hu Z, Thiele DJ, Iyer VR, Genome-Wide Analysis of the Biology of Stress Responses through Heat Shock Transcription Factor, Mol. Cell. Biol 24 (2004) 5249–5256. 10.1128/mcb.24.12.5249-5256.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Morano KA, Grant CM, Moye-Rowley WS, The response to heat shock and oxidative stress in saccharomyces cerevisiae, Genetics. 190 (2012) 1157–1195. 10.1534/genetics.111.128033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pincus D, Anandhakumar J, Thiru P, Guertin MJ, Erkine AM, Gross DS, Genetic and epigenetic determinants establish a continuum of Hsf1 occupancy and activity across the yeast genome, Mol. Biol. Cell 29 (2018) 3168–3182. 10.1091/mbc.E18-06-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hentze N, Le Breton L, Wiesner J, Kempf G, Mayer MP, Molecular mechanism of thermosensory function of human heat shock transcription factor Hsf1, Elife. 5 (2016). 10.7554/eLife.11576.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kmiecik SW, Le Breton L, Mayer MP, Feedback regulation of heat shock factor 1 (Hsf1) activity by Hsp70-mediated trimer unzipping and dissociation from DNA, EMBO J. 39 (2020). 10.15252/embj.2019104096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zheng X, Krakowiak J, Patel N, Beyzavi A, Ezike J, Khalil AS, Pincus D, Dynamic control of Hsf1 during heat shock by a chaperone switch and phosphorylation, Elife. 5 (2016). 10.7554/eLife.18638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zheng X, Beyzavi A, Krakowiak J, Patel N, Khalil AS, Pincus D, Hsf1 Phosphorylation Generates Cell-to-Cell Variation in Hsp90 Levels and Promotes Phenotypic Plasticity, Cell Rep. 22 (2018) 3099–3106. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liebelt F, Sebastian RM, Moore CL, Mulder MPC, Ovaa H, Shoulders MD, Vertegaal ACO, SUMOylation and the HSF1-Regulated Chaperone Network Converge to Promote Proteostasis in Response to Heat Shock, Cell Rep. 26 (2019) 236–249.e4. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Purwana I, Liu JJ, Portha B, Buteau J, HSF1 acetylation decreases its transcriptional activity and enhances glucolipotoxicity-induced apoptosis in rat and human beta cells, Diabetologia. 60 (2017) 1432–1441. 10.1007/s00125-017-4310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lindquist S, Craig EA, The Heat-Shock Proteins, Annu. Rev. Genet 22 (1988) 631–677. 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Solís EJ, Pandey JP, Zheng X, Jin DX, Gupta PB, Airoldi EM, Pincus D, Denic V, Defining the Essential Function of Yeast Hsf1 Reveals a Compact Transcriptional Program for Maintaining Eukaryotic Proteostasis, Mol. Cell 63 (2016) 60–71. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Krakowiak J, Zheng X, Patel N, Feder ZA, Anandhakumar J, Valerius K, Gross DS, Khalil AS, Pincus D, Hsf1 and Hsp70 constitute a two-component feedback loop that regulates the yeast heat shock response, Elife. 7 (2018). 10.7554/eLife.31668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Peffer S, Gonçalves D, Morano KA, Regulation of the Hsf1-dependent transcriptome via conserved bipartite contacts with Hsp70 promotes survival in yeast, J. Biol. Chem 294 (2019) 12191–12202. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.008822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Masser AE, Kang W, Roy J, Kaimal JM, Quintana-Cordero J, Friedländer MR, Andréasson C, Cytoplasmic protein misfolding titrates Hsp70 to activate nuclear Hsf1, Elife. 8 (2019). 10.7554/eLife.47791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Truttmann MC, Zheng X, Hanke L, Damon JR, Grootveld M, Krakowiak J, Pincus D, Ploegh HL, Unrestrained AMPylation targets cytosolic chaperones and activates the heat shock response, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114 (2017) E152–E160. 10.1073/pnas.1619234114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Truttmann MC, Pincus D, Ploegh HL, Chaperone AMPylation modulates aggregation and toxicity of neurodegenerative disease-associated polypeptides, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115 (2018) E5008–E5017. 10.1073/pnas.1801989115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xu L, Nitika, Hasin N, Cuskelly DD, Wolfgeher D, Doyle S, Moynagh P, Perrett S, Jones GW, Truman AW, Rapid deacetylation of yeast Hsp70 mediates the cellular response to heat stress, Sci. Rep 9 (2019). 10.1038/s41598-019-52545-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yang J, Zhang H, Gong W, Liu Z, Wu H, Hu W, Chen X, Wang L, Wu S, Chen C, Perrett S, S-Glutathionylation of human inducible Hsp70 reveals a regulatory mechanism involving the C-terminal α-helical lid, J. Biol. Chem (2020). 10.1074/jbc.ra119.012372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang Y, Gibney PA, West JD, Morano KA, The yeast Hsp70 Ssa1 is a sensor for activation of the heat shock response by thiol-reactive compounds, Mol. Biol. Cell 23 (2012) 3290–3298. 10.1091/mbc.e12-06-0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Miyata Y, Rauch JN, Jinwal UK, Thompson AD, Srinivasan S, Dickey CA, Gestwicki JE, Cysteine reactivity distinguishes redox sensing by the heat-inducible and constitutive forms of heat shock protein 70, Chem. Biol 19 (2012) 1391–1399. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Torrent M, Chalancon G, De Groot NS, Wuster A, Madan Babu M, Cells alter their tRNA abundance to selectively regulate protein synthesis during stress conditions, Sci. Signal 11 (2018). 10.1126/scisignal.aat6409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Damon JR, Pincus D, Ploegh HL, TRNA thiolation links translation to stress responses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Mol. Biol. Cell 26 (2015) 270–282. 10.1091/mbc.E14-06-1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chowdhary S, Kainth AS, Gross DS, Heat Shock Protein Genes Undergo Dynamic Alteration in Their Three-Dimensional Structure and Genome Organization in Response to Thermal Stress, Mol. Cell. Biol 37 (2017). 10.1128/mcb.00292-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chowdhary S, Kainth AS, Pincus D, Gross DS, Heat Shock Factor 1 Drives Intergenic Association of Its Target Gene Loci upon Heat Shock, Cell Rep. 26 (2019) 18–28.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Thamsen M, Ghosh R, Auyeung VC, Brumwell A, Chapman HA, Backes BJ, Perara G, Maly DJ, Sheppard D, Papa FR, Small molecule inhibition of IRE1α kinase/ RNase has anti-fibrotic effects in the lung, PLoS One. 14 (2019) 1–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0209824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu H, Ng BSH, Thibault G, Endoplasmic reticulum stress response in yeast and humans, Biosci. Rep 34 (2014) 321–330. 10.1042/BSR20140058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kohno K, Stress-sensing mechanisms in the unfolded protein response: Similarities and differences between yeast and mammals, J. Biochem 147 (2010) 27–33. 10.1093/jb/mvp196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Promlek T, Ishiwata-Kimata Y, Shido M, Sakuramoto M, Kohno K, Kimata Y, Membrane aberrancy and unfolded proteins activate the endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor Ire1 in different ways, Mol. Biol. Cell 22 (2011) 3520–3532. 10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Credle JJ, Finer-Moore JS, Papa FR, Stroud RM, Walter P, On the mechanism of sensing unfolded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 102 (2005) 18773–18784. 10.1073/pnas.0509487102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pincus D, Chevalier MW, Aragón T, van Anken E, Vidal SE, El-Samad H, Walter P, BiP binding to the ER-stress sensor Ire1 tunes the homeostatic behavior of the unfolded protein response, PLoS Biol. 8 (2010). 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM, Harding HP, Ron D, Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response, Nat. Cell Biol 2 (2000) 326–332. 10.1038/35014014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Amin-Wetzel N, Saunders RA, Kamphuis MJ, Rato C, Preissler S, Harding HP, Ron D, A J-Protein Co-chaperone Recruits BiP to Monomerize IRE1 and Repress the Unfolded Protein Response, Cell. 171 (2017) 1625–1637.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Behnke J, Feige MJ, Hendershot LM, BiP and Its Nucleotide Exchange Factors Grp170 and Sil1: Mechanisms of Action and Biological Functions, J. Mol. Biol 427 (2015) 1589–1608. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Todd-Corlett A, Jones E, Seghers C, Gething MJ, Lobe IB of the ATPase Domain of Kar2p/BiP Interacts with Ire1p to Negatively Regulate the Unfolded Protein Response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, J. Mol. Biol 367 (2007) 770–787. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Carrara M, Prischi F, Nowak PR, Kopp MC, Ali MMU, Noncanonical binding of BiP ATPase domain to Ire1 and Perk is dissociated by unfolded protein CH1 to initiate ER stress signaling, Elife. 2015 (2015) 1–16. 10.7554/eLife.03522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cox JS, Walter P, A novel mechanism for regulating activity of a transcription factor that controls the unfolded protein response, Cell. (1996). 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81360–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K, XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor, Cell. 107 (2001) 881–891. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Thibault G, Ismail N, Ng DTW, The unfolded protein response supports cellular robustness as a broad-spectrum compensatory pathway, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108 (2011) 20597–20602. 10.1073/pnas.1117184109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Van Dalfsen KM, Hodapp S, Keskin A, Otto GM, Berdan CA, Higdon A, Cheunkarndee T, Nomura DK, Jovanovic M, Brar GA, Global Proteome Remodeling during ER Stress Involves Hac1-Driven Expression of Long Undecoded Transcript Isoforms, Dev. Cell 46 (2018) 219–235.e8. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kritsiligkou P, Rand JD, Weids AJ, Wang X, Kershaw CJ, Grant CM, Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress–induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) are detrimental for the fitness of a thioredoxin reductase mutant, J. Biol. Chem 293 (2018) 11984–11995. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.001824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tran DM, Ishiwata-Kimata Y, Mai TC, Kubo M, Kimata Y, The unfolded protein response alongside the diauxic shift of yeast cells and its involvement in mitochondria enlargement, Sci. Rep 9 (2019) 1–14. 10.1038/s41598-019-49146-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D, Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmicreticulum-resident kinase, Nature. 397 (1999) 271–274. 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ye J, Rawson RB, Komuro R, Chen X, Davé UP, Prywes R, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs, Mol. Cell 6 (2000) 1355–1364. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ma Y, Hendershot LM, Delineation of a negative feedback regulatory loop that controls protein translation during endoplasmic reticulum stress, J. Biol. Chem 278 (2003) 34864–34873. 10.1074/jbc.M301107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Marciniak SJ, Yun CY, Oyadomari S, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Jungreis R, Nagata K, Harding HP, Ron D, CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum, Genes Dev. 18 (2004) 3066–3077. 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K, Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress, Mol. Biol. Cell 10 (1999) 3787–3799. 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wang P, Li J, Tao J, Sha B, The luminal domain of the ER stress sensor protein PERK binds misfolded proteins and thereby triggers PERK oligomerization, J. Biol. Chem 293 (2018) 4110–4121. 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Moehle EA, Shen K, Dillin A, Mitochondrial proteostasis in the context of cellular and organismal health and aging, J. Biol. Chem 294 (2019) 5396–5407. 10.1074/jbc.TM117.000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Poveda-Huertes D, Matic S, Marada A, Habernig L, Licheva M, Myketin L, Gilsbach R, Tosal-Castano S, Papinski D, Mulica P, Kretz O, Kücükköse C, Taskin AA, Hein L, Kraft C, Büttner S, Meisinger C, Vögtle FN, An Early mtUPR: Redistribution of the Nuclear Transcription Factor Rox1 to Mitochondria Protects against Intramitochondrial Proteotoxic Aggregates, Mol. Cell 77 (2020) 180–188.e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Nargund AM, Pellegrino MW, Fiorese CJ, Baker BM, Haynes CM, Mitochondrial Import Efficiency of ATFS-1 Regulates Mitochondrial UPR Activation, Science (80-.) 337 (2012) 587–590. 10.1126/science.1223560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nargund AM, Fiorese CJ, Pellegrino MW, Deng P, Haynes CM, Mitochondrial and nuclear accumulation of the transcription factor ATFS-1 promotes OXPHOS recovery during the UPRmt, Mol. Cell 58 (2015) 123–133. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Labbadia J, Brielmann RM, Neto MF, Lin YF, Haynes CM, Morimoto RI, Mitochondrial Stress Restores the Heat Shock Response and Prevents Proteostasis Collapse during Aging, Cell Rep. 21 (2017) 1481–1494. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Fiorese CJ, Schulz AM, Lin YF, Rosin N, Pellegrino MW, Haynes CM, The Transcription Factor ATF5 Mediates a Mammalian Mitochondrial UPR, Curr. Biol 26 (2016) 2037–2043. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zhao Q, Wang J, Levichkin IV, Stasinopoulos S, Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ, A mitochondrial specific stress response in mammalian cells, EMBO J. 21 (2002) 4411–4419. 10.1093/emboj/cdf445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Poirier Y, Grimm A, Schmitt K, Eckert A, Link between the unfolded protein response and dysregulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics in Alzheimer’s disease, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 76 (2019) 1419–1431. 10.1007/s00018-019-03009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kang BH, Plescia J, Dohi T, Rosa J, Doxsey SJ, Altieri DC, Regulation of Tumor Cell Mitochondrial Homeostasis by an Organelle-Specific Hsp90 Chaperone Network, Cell. 131 (2007) 257–270. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Smyrnias I, Gray SP, Okonko DO, Sawyer G, Zoccarato A, Catibog N, López B, González A, Ravassa S, Díez J, Shah AM, Cardioprotective Effect of the Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response During Chronic Pressure Overload, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 73 (2019) 1795–1806. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wrobel L, Topf U, Bragoszewski P, Wiese S, Sztolsztener ME, Oeljeklaus S, Varabyova A, Lirski M, Chroscicki P, Mroczek S, Januszewicz E, Dziembowski A, Koblowska M, Warscheid B, Chacinska A, Mistargeted mitochondrial proteins activate a proteostatic response in the cytosol, Nature. 524 (2015) 485–488. 10.1038/nature14951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Liguori I, Russo G, Curcio F, Bulli G, Aran L, Della-Morte D, Gargiulo G, Testa G, Cacciatore F, Bonaduce D, Abete P, Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases, Clin. Interv. Aging 13 (2018) 757–772. 10.2147/CIA.S158513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Murphy MP, How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species, Biochem. J 417 (2009) 1–13. 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Blevins WR, Tavella T, Moro SG, Blasco-Moreno B, Closa-Mosquera A, Díez J, Carey LB, Albà MM, Extensive post-transcriptional buffering of gene expression in the response to severe oxidative stress in baker’s yeast, Sci. Rep 9 (2019). 10.1038/s41598-019-47424-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Hanzén S, Vielfort K, Yang J, Roger F, Andersson V, Zamarbide-Forés S, Andersson R, Malm L, Palais G, Biteau B, Liu B, Toledano MBB, Molin M, Nyström T, Lifespan Control by Redox-Dependent Recruitment of Chaperones to Misfolded Proteins, Cell. 166 (2016) 140–151. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Rhee SG, Kang SW, Jeong W, Chang TS, Yang KS, Woo HA, Intracellular messenger function of hydrogen peroxide and its regulation by peroxiredoxins, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 17 (2005) 183–189. 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Delaunay A, Pflieger D, Barrault MB, Vinh J, Toledano MB, A thiol peroxidase is an H2O2 receptor and redox-transducer in gene activation, Cell. 111 (2002) 471–481. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Coleman ST, Epping EA, Steggerda SM, Moye-Rowley WS, Yap1p Activates Gene Transcription in an Oxidant-Specific Fashion, Mol. Cell. Biol (1999). 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Sykiotis GP, Bohmann D, Stress-activated cap’n’collar transcription factors in aging and human disease, Sci. Signal 3 (2010) re3–re3. 10.1126/scisignal.3112re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Taguchi K, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Molecular mechanisms of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution, Genes to Cells. 16 (2011) 123–140. 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Suzuki T, Yamamoto M, Stress-sensing mechanisms and the physiological roles of the Keap1– Nrf2 system during cellular stress, J. Biol. Chem 292 (2017) 16817–16824. 10.1074/jbc.R117.800169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Collet JF, D’Souza JC, Jakob U, Bardwell JCA, Thioredoxin 2, an Oxidative Stress-induced Protein, Contains a High Affinity Zinc Binding Site, J. Biol. Chem 278 (2003) 45325–45332. 10.1074/jbc.M307818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Boisnard S, Lagniel G, Garmendia-Torres C, Molin M, Boy-Marcotte E, Jacquet M, Toledano MB, Labarre J, Chédin S, H2O2 activates the nuclear localization of Msn2 and Maf1 through thioredoxins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Eukaryot. Cell 8 (2009) 1429–1438. 10.1128/EC.00106-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Trott A, West JD, Klaić L, Westerheide SD, Silverman RB, Morimoto RI, Morano KA, Activation of heat shock and antioxidant responses by the natural product celastrol: Transcriptional signatures of a thiol-targeted molecule, Mol. Biol. Cell 19 (2008) 1104–1112. 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ahn SG, Thiele DJ, Redox regulation of mammalian heat shock factor 1 is essential for Hsp gene activation and protection from stress, Genes Dev. (2003). 10.1101/gad.1044503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Zhang H, Yang J, Wu S, Gong W, Chen C, Perrett S, Glutathionylation of the bacterial Hsp70 chaperone dnak provides a link between oxidative stress and the heat shock response, J. Biol. Chem 291 (2016) 6967–6981. 10.1074/jbc.M115.673608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].O’Donnell JP, Marsh HM, Sondermann H, Sevier CS, Disrupted Hydrogen-Bond Network and Impaired ATPase Activity in an Hsc70 Cysteine Mutant, Biochemistry. (2018). 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Winter J, Linke K, Jatzek A, Jakob U, Severe oxidative stress causes inactivation of DnaK and activation of the redox-regulated chaperone Hsp33, Mol. Cell 17 (2005) 381–392. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wang J, Sevier CS, Formation and reversibility of BiP protein cysteine oxidation facilitate cell survival during and post oxidative stress, J. Biol. Chem 291 (2016) 7541–7557. 10.1074/jbc.M115.694810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Nicklow EE, Sevier CS, Activity of the yeast cytoplasmic Hsp70 nucleotide-exchange factor Fes1 is regulated by reversible methionine oxidation, J. Biol. Chem 295 (2020) 552–569. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Bartelt-Kirbach B, Golenhofen N, Reaction of small heat-shock proteins to different kinds of cellular stress in cultured rat hippocampal neurons, Cell Stress Chaperones. 19 (2014) 145–153. 10.1007/s12192-013-0452-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Chalova AS, Sudnitsyna MV, Semenyuk PI, Orlov VN, Gusev NB, Effect of disulfide crosslinking on thermal transitions and chaperone-like activity of human small heat shock protein HspB1, Cell Stress Chaperones. 19 (2014) 963–972. 10.1007/s12192-014-0520-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Alderson TR, Roche J, Gastall HY, Dias DM, Pritišanac I, Ying J, Bax A, Benesch JLP, Baldwin AJ, Local unfolding of the HSP27 monomer regulates chaperone activity, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 1–16. 10.1038/s41467-019-08557-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Wemmie JA, Szczypka MS, Thiele DJ, Moye-Rowley WS, Cadmium tolerance mediated by the yeast AP-1 protein requires the presence of an ATP-binding cassette transporter-encoding gene, YCF1, J. Biol. Chem 269 (1994) 32592–32597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Jacobson T, Priya S, Sharma SK, Andersson S, Jakobsson S, Tanghe R, Ashouri A, Rauch S, Goloubinoff P, Christen P, Tamás MJ, Cadmium Causes Misfolding and Aggregation of Cytosolic Proteins in Yeast, Mol. Cell. Biol 37 (2017) 1–15. 10.1128/mcb.00490-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Sharma SK, Goloubinoff P, Christen P, Heavy metal ions are potent inhibitors of protein folding, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 372 (2008) 341–345. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Ford AE, Denicourt C, Morano KA, Thiol stress-dependent aggregation of the glycolytic enzyme triose phosphate isomerase in yeast and human cells, Mol. Biol. Cell 30 (2019) 554–565. 10.1091/mbc.E18-10-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Le QG, Ishiwata-Kimata Y, Kohno K, Kimata Y, Cadmium impairs protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum and induces the unfolded protein response, FEMS Yeast Res. 16 (2016) 49 10.1093/femsyr/fow049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Guerra-Moreno A, Prado MA, Ang J, Schnell HM, Micoogullari Y, Paulo JA, Finley D, Gygi SP, Hanna J, Thiol-based direct threat sensing by the stress-activated protein kinase Hog1, Sci. Signal 12 (2019). 10.1126/scisignal.aaw4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Radzinski M, Fassler R, Yogev O, Breuer W, Shai N, Gutin J, Ilyas S, Geffen Y, Tsytkin-Kirschenzweig S, Nahmias Y, Ravid T, Friedman N, Schuldiner M, Reichmann D, Temporal profiling of redox-dependent heterogeneity in single cells, Elife. 7 (2018) 1–33. 10.7554/eLife.37623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]