Abstract

Aims

Cholinergic neurons are distributed in brain areas containing growth hormone (GH)-responsive cells. We determined if cholinergic neurons are directly responsive to GH and the metabolic consequences of deleting the GH receptor (GHR) specifically in choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-expressing cells.

Main methods

Mice received an acute injection of GH to detect neurons co-expressing ChAT and phosphorylated STAT5 (pSTAT5), a well-established marker of GH-responsive cells. For the physiological studies, mice carrying ablation of GHR exclusively in ChAT-expressing cells were produced and possible changes in energy and glucose homeostasis were determined when consuming regular chow or high-fat diet (HFD).

Key findings

The majority of cholinergic neurons in the arcuate nucleus (60%) and dorsomedial nucleus (84%) of the hypothalamus are directly responsive to GH. Approximately 34% of pre-ganglionic parasympathetic neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus also exhibited GH-induced pSTAT5. GH-induced pSTAT5 in these ChAT neurons was absent in GHR ChAT knockout mice. Mice carrying ChAT-specific GHR deletion, either in chow or HFD, did not exhibit significant changes in body weight, body adiposity, lean body mass, food intake, energy expenditure, respiratory quotient, ambulatory activity, serum leptin levels, glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity and metabolic responses to 2-deoxy-D-glucose. However, GHR deletion in ChAT neurons caused decreased hypothalamic Pomc mRNA levels in HFD mice.

Significance

Cholinergic neurons that regulate the metabolism are directly responsive to GH, although GHR signaling in these cells is not required for energy and glucose homeostasis. Thus, the physiological importance of GH action on cholinergic neurons still needs to be identified.

Keywords: Acetylcholine, ChAT, energy balance, food intake, glucose homeostasis

1. Introduction

Growth hormone (GH) is secreted by the anterior pituitary gland and plays an important role controlling tissue growth and cell proliferation [1]. GH also regulates several metabolic aspects, including body adiposity, free fatty acid mobilization and insulin sensitivity [2, 3]. These effects are possibly mediated by the direct action of GH on metabolically relevant tissues like the adipose tissue, liver and skeletal muscle. Accordingly, genetic ablation of GH receptor (GHR) in such tissues causes metabolic imbalances [4–7].

Although the brain is not classically considered a major target of GH to affect metabolism, recent studies have provided evidence that central GH action modulates numerous metabolic aspects [8]. GH responsive neurons are widely distributed in several hypothalamic and brainstem nuclei involved in the regulation of energy and glucose homeostasis [9]. Importantly, GHR ablation in specific neuronal populations causes marked changes in metabolism [8]. For example, GHR deletion in hypothalamic agouti-related peptide (AgRP)-expressing neurons prevents energy-saving adaptations during food restriction and consequently affects the rate of weight loss [10]. GHR expression in proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-expressing neurons is necessary for the induction of the hyperphagia that occurs during situations of glucoprivation [11]. On the other hand, GH action on steroidogenic factor 1-expressing neurons of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH) regulates the counter regulatory response (CRR) favoring the recovery of hypoglycemia [12]. Central GH action also regulates the metabolism during pregnancy, leading to changes in food intake, fat mass gain and insulin sensitivity [13].

Although these studies have investigated GH action in hypothalamic neurons, the physiological importance of GH signaling in other brain regions is less investigated. GHR is expressed in brainstem noradrenergic neurons, but its biological role is still elusive [14]. An acute GH injection induces phosphorylation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (pSTAT5) in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMX), indicating the presence of functional GHR in this brain area. Accordingly, GHR mRNA expression is observed in the DMX [9]. DMX contains cholinergic neurons that form the efferent vagus nerve [9]. Consequently, choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-expressing cells in the DMX are pre-ganglionic parasympathetic neurons that control energy and glucose homeostasis via the innervation of the upper gastrointestinal tract [15]. Of note, chemogenetic manipulation of parasympathetic DMX neurons causes changes in feeding behavior and energy metabolism [16]. Melanocortin-4 receptor expression in cholinergic or DMX neurons regulates insulin sensitivity [17]. In addition to the importance of ChAT-expressing neurons in the DMX for the regulation of metabolism, recent studies have shown that cholinergic neurons in other brain areas, including the basal forebrain, hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARH) and dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH), are also involved in the control of feeding and metabolism [18–20]. Importantly, GH responsive cells are extensively found in these nuclei [9]. Thus, given the importance of both central GH signaling and cholinergic neurons for the regulation of metabolism, the present study had two major aims. First, we mapped the existence of cholinergic (ChAT positive) neurons that are directly responsive to GH. After identifying these neuronal populations, we produced mice carrying ablation of GHR specifically in ChAT-expressing cells to investigate possible metabolic alterations.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Mice

To produce mice carrying deletion of GHR in cholinergic cells, the ChAT-Cre mouse (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA; RRID: IMSR_JAX:028861) was bred with mice carrying loxP-flanked Ghr alleles [4]. All animals used in these experiments were homozygous for the loxP-flanked Ghr allele. GHR ChAT KO mice were heterozygous for the Cre gene, whereas control group was composed exclusively by their littermates without carrying the Cre transgene. The genotype was confirmed by PCR (REDExtract-N-Amp™ Tissue PCR Kit, Sigma). Male C57BL/6 wild-type mice were used to determine whether cholinergic neurons are directly responsive to GH. Mice were maintained in standard conditions of light (12 h light/dark cycle) and temperature (22 ± 1 °C). The experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences at the University of São Paulo (protocol #73/2017).

2.2. Detection of GH responsive neurons

Adult C57BL/6 and GHR ChAT KO mice (n = 3) received an intraperitoneal injection of GH extracted from porcine pituitary (20 μg/g b.w.; National Hormone and Pituitary Program, Torrance, CA). After 90 min, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with saline followed by 10% buffered formalin. Brains were cryoprotected overnight in 20% sucrose and cut in 30-μm thick sections using a freezing microtome. An immunofluorescent reaction was performed to identify pSTAT5 and ChAT positive neurons in the mouse brain. For this purpose, brain slices were rinsed in 0.02 M potassium PBS, pH 7.4 (KPBS), followed by pretreatment in water solution containing 1% hydrogen peroxide and 1% sodium hydroxide for 20 min. After rinsing in KPBS, sections were incubated in 0.3% glycine and 0.03% lauryl sulfate for 10 min each. Next, slices were blocked in 3% normal donkey serum for 1 h, followed by incubation in a primary antibody cocktail containing anti-pSTAT5Tyr694 raised in rabbit (Cell Signaling, Cat# 9351; RRID: AB_2315225; 1:1,000) and anti-ChAT raised in goat (Millipore, Cat# AB144P; RRID: AB_2079751; 1:400) for 48 hours. Then, sections were rinsed in KPBS and incubated for 90 min in AlexaFluor488-(anti-rabbit IgG) and AlexaFluor594-conjugated (anti-goat IgG) secondary antibodies (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Sections were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides and the slides were covered with Fluoromount G mounting medium (Electron Microscopic Sciences). The photomicrographs were acquired with a Zeiss Axiocam 512 color camera adapted to an Axioimager A1 microscope (Zeiss). Possible co-localizations between GH-induced pSTAT5 and ChAT immunoreactivity were determined in different populations of cholinergic neurons, including the horizontal limb of the diagonal band of Broca (HDB; Bregma 0.745 mm), ARH (Bregma −1.255 mm), DMH (Bregma −1.655 mm), facial motor nucleus (VII; Bregma −5.655 mm), nucleus ambiguous (NA; Bregma −7.255 mm), DMX (Bregma −7.755 mm) and hypoglossal nucleus (XII; Bregma −7.755 mm), according to the Allen Brain Atlas (http://mouse.brain-map.org/).

2.3. Evaluation of energy homeostasis

To determine possible changes in energy homeostasis in mice consuming regular rodent chow (2.99 kcal/g; 9.4% calories from fat), male and female mice were weighed weekly and body composition determined every two weeks, from the fourth to the twentieth week of life. Body composition (fat mass and lean body mass) was determined by time-domain nuclear magnetic resonance using the LF50 body composition mice analyzer (Bruker). After that, mice were single-housed for 5 days for an initial acclimation. Then, food intake was measured for approximately 4 consecutive days. O2 consumption (VO2), CO2 production, ambulatory activity (by infrared sensors) and respiratory exchange ratio (RER; calculated by CO2 production/ O2 consumption) were determined using the Oxymax/Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (Columbus Instruments) for approximately 7 days. The data from the first 2 days of analysis were discarded because we considered acclimation period. The results used for each animal were the average of the analyzed days.

2.4. Evaluation of glucose homeostasis and CCR

Blood glucose levels were determined using a glucose meter (One Touch Ultra; Johnson & Johnson) through samples collected from the tail tip. Approximately 20-week-old mice were subjected to a glucose tolerance test (GTT), insulin tolerance test (ITT) and evaluation of the CRR induced by 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG; Sigma) injection. Food was removed from cage 4 hours before each test, and after evaluation of basal glucose levels (time 0), mice received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of 2 g glucose/kg, 1 IU insulin/kg or 0.5 g 2DG/kg, respectively, followed by serial determinations of glycemia. Glucoprivic hyperphagia was evaluated by recording the cumulative food intake 2, 3 and 4 hours after PBS or 2DG i.p. injections.

2.5. Determination of the susceptibility to diet-induced obesity

In this experiment, 12-week-old GHR ChAT KO and control male mice received a high-fat/high-caloric diet (HFD; cat#D12492, Research Diets Inc.; 5.24 kcal/g; 60% calories from fat) for 14 weeks. Body weight, body composition, food intake, VO2, RER and ambulatory activity were determined as formerly described. Additionally, GTT, ITT and the CRR to 2DG were also evaluated. Hepatic steatosis was determined by nuclear magnetic resonance, as previously described [21].

2.6. Tissue collection and analysis

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by decapitation. Serum was obtained from trunk blood to determine leptin levels using ELISA (Quantikine® ELISA #MOB00, R&D, USA). Leptin ELISA kit has a detection limit of 22 pg/mL, and an intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variability ≤ 6%. Brain, liver, perigonadal adipose tissue and gastrocnemius muscle masses were determined. The whole hypothalamus of HFD mice was removed, quickly frozen, followed by extraction of total RNA with TRIzol® (Invitrogen). Assessment of RNA quantity and quality was performed with an Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (Biotek). Total RNA was incubated with RNase-free DNase I (Roche Applied Science). Reverse transcription was performed with 2 μg of total RNA using SuperScript® II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random primers p(dN)6 (Roche Applied Science). Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed using the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The following primers were used: Actb (forward: gctccggcatgtgcaaag; reverse: catcacaccctggtgccta), Agrp (forward: ctttggcggaggtgctagat; reverse: aggactcgtgcagccttacac), Gapdh (forward: gggtcccagcttaggttcat; reverse: tacggccaaatccgttcaca), Ghrh (forward: tatgcccggaaagtgatccag; reverse: atccttgggaatccctgcaaga), Npy (forward: ccgcccgccatgatgctaggta; reverse: ccctcagccagaatgcccaa), Pomc (forward: atagacgtgtggagctggtgc; reverse: gcaagccagcaggttgct), Ppia (forward: tatctgcactgccaagactgagt; reverse: cttcttgctggtcttgccattcc) and Sst (forward: ctgtcctgccgtctccagt; reverse: ctgcagaaactgacggagtct). The relative quantification of mRNA was calculated by 2−ΔΔCt. Data were normalized by the geometric average of Actb, Gapdh and Ppia.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare control and GHR ChAT KO groups. Changes along time were evaluated by repeated measures two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. The GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) was used for the statistical analyses. Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of cholinergic neurons responsive to GH in the mouse brain

Brain areas where cholinergic neurons are found [16–20] also contain significant numbers of GH-responsive neurons [9]. To investigate whether cholinergic neurons are directly responsive to GH, C57BL/6 mice received an acute systemic injection of GH and their brains were processed to detect cells co-expressing ChAT and pSTAT5, a well-established marker of GH-responsive neurons [9–14]. In the basal forebrain, a large number of ChAT positive neurons were observed along the HDB; however, very few neurons (<1%) co-localized with pSTAT5 (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, in the hypothalamus, 60 ± 19% of ChAT neurons in the ARH exhibited GH-induced pSTAT5 (Fig. 1B). Additionally, 84 ± 16% of cholinergic neurons in the DMH displayed pSTAT5 in GH-injected mice (Fig. 1C). In the brainstem, pSTAT5 cells were not found in the NA (Fig. 1D). Several pSTAT5 positive cells were observed in the VII and XII, but they did not co-localize with ChAT neurons (Fig. 1E-F). However, 34 ± 6% of ChAT positive neurons in the DMX expressed GH-induced pSTAT5 (Fig. 1F). Of note, GH-responsive neurons in the DMX were concentrated in the lateral and caudal divisions, representing a segregated neuronal population, compared with rostral and medial DMX ChAT neurons (Fig. 1F). PBS-injected mice exhibited few pSTAT5 cells in the entire brain and no co-localization with ChAT (data not shown). Altogether, an important percentage of GH-responsive neurons were observed in cholinergic neurons located in the ARH, DMH and DMX, all nuclei critically involved in the regulation of energy and glucose homeostasis [16, 17, 19, 20].

Figure 1.

Cholinergic neurons are directly responsive to GH. A-I. Epifluorescence photomicrographs of the mouse brain displaying the co-localization between ChAT (red staining) and GH-induced pSTAT5 (green nuclear staining) in wild-type mice (A-F) and GHR ChAT KO mice (G-I). The insets represent higher magnification images of the selected areas. Examples of cholinergic neurons that are responsive to GH are indicated by arrowheads. Abbreviations: 3V, third ventricle; VII, facial motor nucleus; XII, hypoglossal nucleus; ARH, arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus; cc, central channel; DMH, dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus; DMX, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; HDB, horizontal limb of the diagonal band of Broca; NA, nucleus ambiguous; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; VMH, ventromedial nucleus. Scale Bar = 200 μm in A, 100 μm in B-C, 200 μm in D-F, 100 μm in G-H, and 200 μm in I.

3.2. GHR ablation in ChAT neurons does not affect energy homeostasis or tissue growth

After demonstrating that cholinergic neurons in brain areas that regulate metabolism are directly responsive to GH, we decided to investigate the physiological importance played by GHR signaling in these cells. For this purpose, we produced mice carrying ablation of GHR exclusively in ChAT-expressing cells. To confirm the targeted gene deletion, GHR ChAT KO mice received a GH injection to induce pSTAT5 in the brain. As shown in wild-type mice (Fig. 1A-F), GH injection led to a great number of pSTAT5 immunoreactive cells all over the brain, including hypothalamic areas like the ARH (Fig. 1G), VMH (Fig. 1G) and DMH (Fig. 1H), a well as the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS; Fig. 1H). However, in contrast to wild-type animals, ChAT neurons did not co-localize with GH-induced pSTAT5 in GHR ChAT KO mice (Fig. 1G-I), indicating that GHR ablation affected specifically cholinergic neurons.

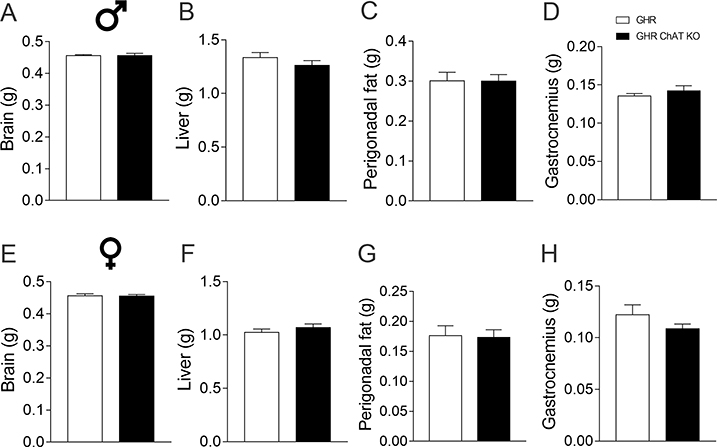

Then, we investigated possible changes in energy balance in GHR ChAT KO mice. In both males and females, GHR deletion in ChAT-expressing cells did not cause any alterations in body weight, body fat mass, lean body mass, daily food intake, energy expenditure (VO2), RER, voluntary ambulatory activity and serum leptin levels (Fig. 2). Muscarinic cholinergic receptors regulate GH secretion in humans [22] and mice [23]. Thus, we also investigated whether GHR ChAT KO mice exhibit normal tissue growth, as an indicator of possible changes in GH secretion. We observed a similar brain, liver, perigonadal fat and gastrocnemius muscle weight comparing control and GHR ChAT KO mice (Fig. 3). Additionally, control and GHR ChAT KO male mice exhibited similar Ghrh (control: 1.00 ± 0.14; GHR ChAT KO: 0.80 ± 0.09; t(14) = 1.232, p = 0.2383) and Sst (control: 1.00 ± 0.18; GHR ChAT KO: 1.11 ± 0.07; t(14) = 0.73, p = 0.4775) mRNA levels in the hypothalamus.

Figure 2.

GHR ablation in ChAT neurons does not affect energy homeostasis. A-H. Body weight (A), body fat mass (B), lean body mass (C), daily food intake (D), oxygen consumption (VO2, E), respiratory exchange ratio (RER, F), ambulatory activity (G) and serum leptin levels (H) in control (n = 8–11) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 8–14) male mice. I-P. Body weight (I), body fat mass (J), lean body mass (K), daily food intake (L), VO2 (M), RER (N), ambulatory activity (O) and serum leptin levels (P) in control (n = 8–12) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 8–10) female mice.

Figure 3.

GHR ablation in ChAT neurons does not affect tissue growth. A-D. Brain (A), liver (B), perigonadal fat (C) and gastrocnemius muscle (D) mass in control (n = 11) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 14) male mice. E-H. Brain (E), liver (F), perigonadal fat (G) and gastrocnemius muscle (H) mass in control (n = 12) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 10) female mice.

3.3. Normal glucose homeostasis in mice carrying GHR ablation in ChAT neurons

ChAT neurons, particularly in the DMX, regulate glucose levels [16, 17]. Thus, we also evaluated possible changes in glucose homeostasis and we observed that GHR ablation in ChAT-expressing neurons did not cause significant alterations in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in male (Fig. 4A-B) and female mice (Fig. 4E-F). Central GHR signaling regulates the CRR to hypoglycemia and the hyperphagia induced by 2DG [10–12]. However, GHR ChAT KO mice showed a similar 2DG-induced CRR and hyperphagia, compared to control animals (Fig. 4C-D, G-H). Therefore, GHR expression in ChAT neurons is not required for the regulation of glucose homeostasis.

Figure 4.

Normal glucose homeostasis in mice carrying GHR ablation in ChAT neurons. A-D. Glucose tolerance test (A), insulin tolerance test (B), counter regulatory response to 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG, C) and glucoprivic hyperphagia after PBS or 2DG injections (D) in control (n = 11) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 14) male mice. E-H. Glucose tolerance test (E), insulin tolerance test (F), counter regulatory response to 2DG (G) and glucoprivic hyperphagia after PBS or 2DG injections (H) in control (n = 12) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 10) female mice.

3.4. Reduced hypothalamic Pomc expression in HFD GHR ChAT KO mice

In the next set of experiments, we evaluated the susceptibility to diet-induced obesity by exposing control and GHR ChAT KO male mice to HFD for 14 weeks (Fig. 5). We observed a similar body weight gain over time between the groups (Fig. 5A). Additionally, the increases in body fat mass and lean body mass were not different between control and GHR ChAT KO mice (Fig. 5B-C). No statistically significant differences in food intake (Fig. 5D), VO2 (Fig. 5E), RER (Fig. 5F), ambulatory activity (Fig. 5G), serum leptin levels (Fig. 5H), glucose tolerance (Fig. 6A), insulin sensitivity (Fig. 6B), CRR to 2DG injection (Fig. 6C) and liver adipose content (Fig. 6D) were observed in control and GHR ChAT KO male mice. Hypothalamic gene expression was analyzed in mice exposed to HFD and we observed normal Agrp and Npy mRNA levels in GHR ChAT KO mice (Fig. 6E-F). However, GHR deletion in ChAT neurons caused decreased hypothalamic Pomc mRNA levels in HFD mice (t(12) = 2.644, p = 0.0214; Fig. 6G).

Figure 5.

GHR ablation in ChAT neurons does not affect the energy balance in male mice consuming high-fat diet. A-H. Body weight (A), body fat mass (B), lean body mass (C), daily food intake (D), oxygen consumption (VO2, E), respiratory exchange ratio (RER, F), ambulatory activity (G) and serum leptin levels (H) in control (n = 7) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 11) male mice consuming high-fat diet for 14 weeks.

Figure 6.

Reduced hypothalamic Pomc expression in HFD GHR ChAT KO mice. A-C. Glucose tolerance test (A), insulin tolerance test (B) and counter regulatory response to 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG, C) in HFD control (n = 11) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 14) male mice. D. Liver adipose content in control (n = 4) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 6) male mice after 14 weeks in high-fat diet. E-G. Hypothalamic mRNA levels in control (n = 5) and GHR ChAT KO (n = 11) male mice after 14 weeks in high-fat diet. *, p = 0.0214.

4. Discussion

Numerous hormones, including insulin [24, 25], leptin [26], ghrelin [27, 28] and prolactin [29], act via the central nervous system to regulate feeding and metabolism. Recently, several studies have shown that central GH infusion increases food intake and GHR deletion in specific neuronal populations produces metabolic and neuroendocrine consequences [8, 10–14, 30–32]. In the present study, we investigated whether cholinergic neurons are central mediators of GH to control metabolism.

Acetylcholine is a common neurotransmitter involved in many neurological processes, such as the control of muscle contraction, visceral functions, arousal, learning, memory, reward and cognition. In the last years, populations of cholinergic neurons involved in the regulation of feeding and metabolism were identified, including those located in the basal forebrain/HDB [18], DMH [19] and ARH [20]. Although the role played by HDB neurons regulating metabolism was only recently described [18], DMH and ARH neurons are well-known components of the hypothalamic neurocircuit that control feeding, energy expenditure, thermogenesis and body weight [10, 11, 13, 26, 31, 33–35]. Importantly, both DMH and ARH contain a large number of GH-responsive neurons [9–11]. In the present study, we showed that the majority of ChAT positive cells in the DMH and ARH exhibit GH-induced pSTAT5, indicating that these acetylcholine-producing neurons express GHR. Jeong and colleagues [19] demonstrated that downregulation of ChAT in the DMH decreases the body weight of mice, whereas chemogenetic activation of these neurons increases food intake. Furthermore, activation of cholinergic axons that innervate the ARH enhances GABAergic transmission to POMC neurons, suggesting that ARH POMC-expressing cells are mediators of the metabolic effects induced by DMH ChAT neurons [19]. Therefore, GH possibly has an inhibitory effect on DMH cholinergic neurons. In this sense, the absence of GH action in GHR ChAT KO mice would cause disinhibition of DMH cholinergic neurons, which in turn, would lead to a greater inhibitory input onto POMC neurons, possibly decreasing the expression of Pomc mRNA, as observed in the GHR ChAT KO mice. Interestingly, POMC expression is found in a subpopulation of cholinergic neurons of the ARH [20, 36]. Thus, a direct action of GH on POMC neurons may also account for the changes observed in hypothalamic Pomc expression.

Given the presence of GHR in critical neuronal populations that regulate metabolism and the consequent downregulation of hypothalamic Pomc mRNA levels, it is somewhat surprising that GHR ChAT KO mice did not exhibit any metabolic imbalance, even when challenged with HFD. We hypothesize that the various redundant mechanisms that control feeding and metabolism [26, 37, 38] were able to compensate for the changes in POMC neurons. Not always changes in hypothalamic Pomc expression lead to predicted metabolic outcomes, considering the dominant anorexigenic action of POMC neurons. For example, ovariectomized mice become obese despite increased Pomc expression in the hypothalamus [39]. In another study, mice with increased leptin sensitivity and decreased body adiposity display reduced hypothalamic Pomc expression [40], even though leptin signaling increases the neuronal activity of POMC neurons [26, 37, 38]. Thus, the reduced Pomc expression in the hypothalamus of GHR ChAT KO mice provides additional evidence that POMC and cholinergic neurons are linked [19, 20, 36], but this change alone is not sufficient to cause significant changes in energy and glucose homeostasis.

GH-induced pSTAT5 was also observed in a subgroup of ChAT neurons in the DMX. These pre-ganglionic parasympathetic neurons regulate several autonomic functions of thoracic and abdominal organs [15]. Changes in the activity of DMX neurons produce alterations in feeding, energy balance and glucose homeostasis [16, 17]. Notably, most of GH-responsive neurons were specifically located in the lateral and caudal divisions of the DMX, whereas only few GH-induced pSTAT5 positive cells co-localized with ChAT neurons in the rostral and medial divisions of the DMX. This particular spatial distribution probably has a physiological meaning because there is evidence of a topographic visceral representation in the DMX [41, 42]. In this sense, Fox and Powley [41] showed that neurons in the caudal-lateral division of the DMX mainly innervate the celiac subdiaphragmatic vagal branches, while neurons distributed in other parts of the DMX innervate the hepatic and gastric parasympathetic branches. Therefore, GH action on DMX neurons likely regulates visceral functions via the vagal innervation to the celiac plexus, suppling nerve terminals to esophagus, liver, stomach, pylorus, duodenum and pancreas [43]. Noteworthy, GHR deletion in VMH neurons leads to an abnormal hyperactivity of parasympathetic preganglionic neurons in the DMX, impairing the capacity of mice to recover from hypoglycemia [12]. Thus, our findings add new evidence that central GH signaling is able to influence the parasympathetic nervous system. In this regard, although we did not observe significant metabolic consequences in mice carrying deletion of GHR in ChAT neurons, we cannot rule out the possibility that physiological aspects regulated by the vagus nerve in the upper gastrointestinal tract may be compromised in GHR ChAT KO mice.

5. Conclusions

Cholinergic neurons in the hypothalamus and medulla oblongata are directly responsive to GH. Although these ChAT-expressing neurons are involved in the regulation of metabolism, GHR signaling in these cells is not required for energy and glucose homeostasis. Our findings provide further support that POMC neurons are under the influence of cholinergic neurons (or express ChAT) because GHR deletion in ChAT-expressing cells decreased hypothalamic Pomc mRNA levels. The responsiveness to GH in a subpopulation of DMX neurons that innervate the upper gastrointestinal tract may indicate that central GH signaling is implicated in the vagal control of visceral functions. However, the identification of the physiological importance of GH action on these cholinergic neurons will require future studies to investigate autonomic functions that were not evaluated in the present study. Nevertheless, our findings contribute to the discovery of novel neuronal populations that may mediate the biological effects of GH.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP/Brazil; Grant numbers: 16/20897–3 to F.W., 17/25281–3 to P.G.F.Q. and 17/02983–2 to J.D.) and NIH (NIA; grant number: R01AG059779 to E.O.L. and J.J.K.). P.D.S.T. and J.D. received fellowships from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq/Brazil).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Steyn FJ, Tolle V, Chen C, Epelbaum J, Neuroendocrine Regulation of Growth Hormone Secretion, Compr Physiol 6 (2016) 687–735. 10.1002/cphy.c150002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moller N, Jorgensen JO, Effects of growth hormone on glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism in human subjects, Endocr Rev 30 (2009) 152–77. 10.1210/er.2008-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Salomon F, Cuneo RC, Hesp R, Sonksen PH, The effects of treatment with recombinant human growth hormone on body composition and metabolism in adults with growth hormone deficiency, N Engl J Med 321 (1989) 1797–803. 10.1056/NEJM198912283212605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].List EO, Berryman DE, Funk K, Gosney ES, Jara A, Kelder B, et al. , The role of GH in adipose tissue: lessons from adipose-specific GH receptor gene-disrupted mice, Mol Endocrinol 27 (2013) 524–35. 10.1210/me.2012-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].List EO, Berryman DE, Funk K, Jara A, Kelder B, Wang F, et al. , Liver-specific GH receptor gene-disrupted (LiGHRKO) mice have decreased endocrine IGF-I, increased local IGF-I, and altered body size, body composition, and adipokine profiles, Endocrinology 155 (2014) 1793–805. 10.1210/en.2013-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].List EO, Berryman DE, Ikeno Y, Hubbard GB, Funk K, Comisford R, et al. , Removal of growth hormone receptor (GHR) in muscle of male mice replicates some of the health benefits seen in global GHR−/− mice, Aging 7 (2015) 500–12. 10.18632/aging.100766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].List EO, Berryman DE, Buchman M, Parker C, Funk K, Bell S, et al. , Adipocyte-Specific GH Receptor-Null (AdGHRKO) Mice Have Enhanced Insulin Sensitivity With Reduced Liver Triglycerides, Endocrinology 160 (2019) 68–80. 10.1210/en.2018-00850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wasinski F, Frazão R, Donato JJ, Effects of growth hormone in the central nervous system, Arch Endocrinol Metab 63 (2019) 549–56. 10.20945/2359-399700000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Furigo IC, Metzger M, Teixeira PD, Soares CR, Donato J Jr., Distribution of growth hormone-responsive cells in the mouse brain, Brain Struct Funct 222 (2017) 341–63. 10.1007/s00429-016-1221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Furigo IC, Teixeira PDS, de Souza GO, Couto GCL, Romero GG, Perello M, et al. , Growth hormone regulates neuroendocrine responses to weight loss via AgRP neurons, Nat Commun 10 (2019) 662 10.1038/s41467-019-08607-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Quaresma PGF, Teixeira PDS, Furigo IC, Wasinski F, Couto GC, Frazao R, et al. , Growth hormone/STAT5 signaling in proopiomelanocortin neurons regulates glucoprivic hyperphagia, Mol Cell Endocrinol 498 (2019) 110574 10.1016/j.mce.2019.110574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Furigo IC, de Souza GO, Teixeira PDS, Guadagnini D, Frazao R, List EO, et al. , Growth hormone enhances the recovery of hypoglycemia via ventromedial hypothalamic neurons, FASEB J 33 (2019) 11909–24. 10.1096/fj.201901315R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Teixeira PDS, Couto GC, Furigo IC, List EO, Kopchick JJ, Donato J Jr., Central growth hormone action regulates metabolism during pregnancy, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 317 (2019) E925–E40. 10.1152/ajpendo.00229.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wasinski F, Pedroso JAB, Dos Santos WO, Furigo IC, Garcia-Galiano D, Elias CF, et al. , Tyrosine Hydroxylase Neurons Regulate Growth Hormone Secretion via Short-Loop Negative Feedback, J Neurosci 40 (2020) 4309–22. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2531-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gautron L, Rutkowski JM, Burton MD, Wei W, Wan Y, Elmquist JK, Neuronal and nonneuronal cholinergic structures in the mouse gastrointestinal tract and spleen, J Comp Neurol 521 (2013) 3741–67. 10.1002/cne.23376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].NamKoong C, Song WJ, Kim CY, Chun DH, Shin S, Sohn JW, et al. , Chemogenetic manipulation of parasympathetic neurons (DMV) regulates feeding behavior and energy metabolism, Neurosci Lett 712 (2019) 134356 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rossi J, Balthasar N, Olson D, Scott M, Berglund E, Lee CE, et al. , Melanocortin-4 receptors expressed by cholinergic neurons regulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis, Cell Metab 13 (2011) 195–204. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Herman AM, Ortiz-Guzman J, Kochukov M, Herman I, Quast KB, Patel JM, et al. , A cholinergic basal forebrain feeding circuit modulates appetite suppression, Nature 538 (2016) 253–6. 10.1038/nature19789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jeong JH, Lee DK, Jo YH, Cholinergic neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus regulate food intake, Mol Metab 6 (2017) 306–12. 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jeong JH, Woo YJ, Chua S Jr., Jo YH, Single-Cell Gene Expression Analysis of Cholinergic Neurons in the Arcuate Nucleus of the Hypothalamus, PLoS One 11 (2016) e0162839 10.1371/journal.pone.0162839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pedroso JAB, Camporez JP, Belpiede LT, Pinto RS, Cipolla-Neto J, Donato J Jr., Evaluation of Hepatic Steatosis in Rodents by Time-Domain Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, Diagnostics (Basel) 9 (2019) 198 10.3390/diagnostics9040198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Harada T, Yamauchi T, Tsukanaka A, Matsumura Y, Kurono M, Honda A, et al. , Involvement of muscarinic cholinergic and alpha2-adrenergic mechanisms in growth hormone secretion during exercise in humans, Eur J Appl Physiol 83 (2000) 268–73. 10.1007/s004210000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gautam D, Jeon J, Starost MF, Han SJ, Hamdan FF, Cui Y, et al. , Neuronal M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors are essential for somatotroph proliferation and normal somatic growth, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (2009) 6398–403. 10.1073/pnas.0900977106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Porte D Jr., Woods SC, Regulation of food intake and body weight in insulin, Diabetologia 20 Suppl (1981) 274–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Brüning JC, Gautam D, Burks DJ, Gillette J, Schubert M, Orban PC, et al. , Role of Brain Insulin Receptor in Control of Body Weight and Reproduction, Science 289 (2000) 2122–5. 10.1126/science.289.5487.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ramos-Lobo AM, Donato J Jr., The role of leptin in health and disease, Temperature 4 (2017) 258–91. 10.1080/23328940.2017.1327003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tschop M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML, Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents, Nature 407 (2000) 908–13. 10.1038/35038090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K, et al. , A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding, Nature 409 (2001) 194–8. 10.1038/35051587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Furigo IC, Suzuki MF, Oliveira JE, Ramos-Lobo AM, Teixeira PDS, Pedroso JA, et al. , Suppression of Prolactin Secretion Partially Explains the Antidiabetic Effect of Bromocriptine in ob/ob Mice, Endocrinology 160 (2019) 193–204. 10.1210/en.2018-00629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wasinski F, Furigo IC, Teixeira PDS, Ramos-Lobo AM, Peroni CN, Bartolini P, et al. , Growth Hormone Receptor Deletion Reduces the Density of Axonal Projections from Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus Neurons, Neuroscience 434 (2020) 136–47. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Furigo IC, Teixeira PD, Quaresma PGF, Mansano NS, Frazao R, Donato J, STAT5 ablation in AgRP neurons increases female adiposity and blunts food restriction adaptations, J Mol Endocrinol 64 (2020) 13–27. 10.1530/JME-19-0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bohlen TM, Zampieri TT, Furigo IC, Teixeira PD, List EO, Kopchick J, et al. , Central growth hormone signaling is not required for the timing of puberty, J Endocrinol 243 (2019) 161–73. 10.1530/JOE-19-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mieda M, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Tanaka K, Yanagisawa M, The dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus as a putative food-entrainable circadian pacemaker, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 (2006) 12150–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chao PT, Yang L, Aja S, Moran TH, Bi S, Knockdown of NPY expression in the dorsomedial hypothalamus promotes development of brown adipocytes and prevents diet-induced obesity, Cell Metab 13 (2011) 573–83. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Enriori PJ, Sinnayah P, Simonds SE, Garcia Rudaz C, Cowley MA, Leptin action in the dorsomedial hypothalamus increases sympathetic tone to brown adipose tissue in spite of systemic leptin resistance, J Neurosci 31 (2011) 12189–97. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2336-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Meister B, Gomuc B, Suarez E, Ishii Y, Durr K, Gillberg L, Hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons have a cholinergic phenotype, Eur J Neurosci 24 (2006) 2731–40. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Andreoli MF, Donato J, Cakir I, Perello M, Leptin resensitisation: a reversion of leptin-resistant states, J Endocrinol 241 (2019) R81–R96. 10.1530/JOE-18-0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Andermann ML, Lowell BB, Toward a Wiring Diagram Understanding of Appetite Control, Neuron 95 (2017) 757–78. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].da Silva RP, Zampieri TT, Pedroso JA, Nagaishi VS, Ramos-Lobo AM, Furigo IC, et al. , Leptin resistance is not the primary cause of weight gain associated with reduced sex hormone levels in female mice, Endocrinology 155 (2014) 4226–36. 10.1210/en.2014-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pedroso JA, Buonfiglio DC, Cardinali LI, Furigo IC, Ramos-Lobo AM, Tirapegui J, et al. , Inactivation of SOCS3 in leptin receptor-expressing cells protects mice from diet-induced insulin resistance but does not prevent obesity, Mol Metab 3 (2014) 608–18. 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Fox EA, Powley TL, Longitudinal columnar organization within the dorsal motor nucleus represents separate branches of the abdominal vagus, Brain Res 341 (1985) 269–82. 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kalia M, Brain stem localization of vagal preganglionic neurons, J Auton Nerv Syst 3 (1981) 451–81. 10.1016/0165-1838(81)90081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Berthoud HR, Powley TL, Characterization of vagal innervation to the rat celiac, suprarenal and mesenteric ganglia, J Auton Nerv Syst 42 (1993) 153–69. 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90046-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]