Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate socioeconomic determinants of fecundability.

Methods

Among 8,654 female pregnancy planners from Pregnancy Study Online, a North American prospective cohort study (2013–2019), we examined associations between socioeconomic status and fecundability (the per-cycle probability of conception). Information on income and education was collected via baseline questionnaire. Bimonthly follow-up questionnaires were used to ascertain pregnancy status. We estimated fecundability ratios (FRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using proportional probabilities regression, controlling for potential confounders.

Results

Relative to an annual household income of ≥$150,000, adjusted FRs were 0.91 (95% CI: 0.83–1.01) for <$50,000, 0.99 (95% CI: 0.92–1.07) for $50,000-$99,000, and 1.09 (95% CI: 1.01–1.18) for $100,000-$149,000. FRs for <12, 13–15, and 16 years of education, relative to ≥17 years, were 0.90 (95% CI: 0.76–1.08), 0.84 (95% CI: 0.78–0.91), and 0.89 (95% CI: 0.84–0.95), respectively. Slightly stronger associations for income and education were seen among older women.

Conclusions

Lower levels of education and income were associated with modestly reduced fecundability. These results demonstrate the presence of socioeconomic disparities in fecundability.

Keywords: fecundability, time-to-pregnancy, income, education, socioeconomic status, social determinants of health

Background

In the United States (US), and to a lesser extent in Canada, there are well-documented socioeconomic disparities in cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality.1–5 Though socioeconomic status (SES) is widely considered a fundamental determinant of health,6 few studies, have investigated SES disparities in fecundity, the biological capacity to reproduce.7, 8 One measure of fecundity, infertility, is defined as the inability to conceive after 12 months of unprotected intercourse. Infertility affects 10–15% of couples in the US and Canada,9, 10 can cause psychological and financial hardship,11 and is associated with $5 billion in annual health care costs.12 In contrast, high fecundity may be associated with unplanned or mistimed pregnancies, which may adversely affect several maternal and child health outcomes.13–18

There has been limited and conflicting research on the extent to which measures of SES, such as educational attainment or income,19 influence fecundity-related outcomes. In the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), a nationally-representative study of married or cohabitating women aged 15–44 years, women with lower educational attainment had a higher prevalence of infertility and impaired fecundity (defined as difficulty becoming pregnant and carrying a fetus to term), and longer median time-to-pregnancy (TTP). On the other hand, lower income was associated with improved fecundity and shorter median TTP).10 In the nationally-representative Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, women with less education were more likely to report infertility, and difficulty paying for basic necessities was associated with infertility among Black but not White women.20 In a study of infertility patients, education was positively associated with seeking medical evaluation for infertility, but income was not.21

The use of varied definitions to measure infertility could explain the conflicting associations reported in previous studies,7, 8 especially if pregnancy planning differs by socio-demographic characteristics.22–25 Moreover, unmeasured behavioral and lifestyle patterns could confound or mediate comparisons of infertility rates across SES groups.26, 27 Additionally, infertility rates are limited to women who have been attempting pregnancy for 12 months. An improved measure of fecundity is fecundability, the per-cycle probability of conception in a given menstrual cycle.

In a prospective cohort study of North American pregnancy planners, we examined differences in fecundability according to socioeconomic status, as measured by annual household income and educational attainment.

Methods

Study population

Pregnancy Study Online (PRESTO) is an ongoing prospective preconception cohort study of female pregnancy planners and their male partners in the US and Canada. The study methodology has been described in detail elsewhere.28 Initiated in June 2013, PRESTO recruits participants via advertising on social media and health-related websites. Eligible women are aged 21–45 years, not using contraception or fertility treatments, in a stable relationship with a male partner, and not currently pregnant. The Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and all participants provided informed consent.

Study procedures

Participants completed an online baseline questionnaire to provide detailed information on demographics, including nationality, anthropometrics, medical and reproductive history, and lifestyle and behavioral habits. Updated exposure information and pregnancy status were obtained by online follow-up questionnaires every 2 months for up to 12 months or until reported pregnancy. Over 80% of participants completed at least one follow-up questionnaire.28

Assessment of socioeconomic status

We operationalized socioeconomic status using measures of annual household income and educational attainment.19 On the baseline questionnaire, women reported their total annual household income (in US dollars) before tax in several categories: <$15,000; $15,000-$24,999; $25,000-$49,999; $50,000-$74,999; $75,000-$99,999; $100,000-$124,999; $125,000-$149,999; $150,000-$199,999; and ≥$200,000. Annual household income was then collapsed into four categories for the analyses: <$50,000; $50,000-$99,999; $100,000-$149,000, and ≥$150,000.

Women reported their highest level of completed education on the baseline questionnaire. Responses were then collapsed into the following categories: less than 12th grade or high school degree or equivalent (≤12 years); some college/vocational school (13–15 years); four-year college degree (16 years); and graduate degree (≥17 years).

Assessment of fecundability

We estimated fecundability, the average per-cycle probability of conception, via direct measurement of TTP. TTP was derived from baseline and follow-up questionnaires. At baseline, women reported the date of their last menstrual period (LMP), cycle regularity, average menstrual cycle length, and the number of cycles they had been trying to conceive at study entry. Women with irregular cycles reported their typical number of periods per year. On each follow-up questionnaire, we asked about most recent LMP date and whether they had conceived or initiated fertility treatment since the completion of the previous questionnaire. We attempted to identify outcome information on women lost to follow-up by contacting them directly, searching for baby registries and birth announcements online, and/or linking to birth registry data from select states. We calculated total discrete menstrual cycles at risk of pregnancy using the following equation: cycles of attempt at study entry + [(LMP date from most recent follow-up questionnaire - date of baseline questionnaire completion)/usual cycle length] +1.

Assessment of covariates

On the baseline questionnaire, women reported data on current age; height and weight; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic/Latina, or mixed/other race); vigorous physical activity (average hours per week spent biking, jogging, swimming, racquetball, aerobic activities, or weight training/resistance exercising); parity; cigarette smoking; alcohol consumption; intercourse frequency; menstrual cycle regularity; history of infertility; history of sexually transmitted infections (ever diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease, chlamydia, genital warts, herpes, or bacterial vaginosis); whether they were doing something to improve their chances of contraception (e.g., menstrual charting, use of ovulation tests); last method of contraception used; educational attainment of their mother, father, primary caregiver (if not mother or father), and their male partner; marital status (currently married vs. not); sleep duration; employment status and hours worked per week; perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale-10, PSS);29 and depressive symptoms (Major Depression Inventory, MDI).30 We ascertained dietary intake on food frequency questionnaires completed ten days after baseline, from which we calculated the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) score.31, 32 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Exclusions

Between July 2013 and August 2019, 10,988 women completed the baseline questionnaire. We excluded women from this analysis whose LMP occurred more than 6 months before completing the baseline questionnaire or with an implausible LMP (n=129); who did not experience menses during follow-up (n=24); or had been trying to conceive for more than 6 menstrual cycles at study entry (n=2,181), to reduce potential for selection bias.

Data analysis

We calculated the proportion of women who conceived over follow-up using life table methods to account for censoring.33 Women contributed observed menstrual cycles to the analysis from study entry until pregnancy, fertility treatment, cessation of pregnancy attempt, loss to follow-up, or 12 cycles, whichever came first. We used proportional probabilities regression models to estimate fecundability ratios (FR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each exposure category relative to the reference category. The FR is the ratio of fecundability comparing exposed with unexposed women; an FR<1 corresponds to reduced fecundability among the exposed relative to the unexposed. We used the Anderson-Gill data structure34 with one observation per menstrual cycle, to update covariates over time and to account for left truncation due to delayed entry into the risk set.35, 36

We selected potential confounders a priori from the literature and construction of directed acyclic graphs. Models were adjusted for age (years), male partner educational attainment (≤12, 13–15, 16, ≥17 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and mixed/other race), and mutually-adjusted for the other exposure variable (e.g., education analyses were adjusted for income).

In additional models, we estimated the direct effect of income and education on fecundability that does not operate through other behavioral and health variables that are mediators of the association between exposure and outcome. These models were adjusted for the variables included in Model 1 and marital status (currently married vs. no), BMI (kg/m2), smoking (never, past, and current smoking), vigorous physical activity (0, <1, 1–2, 3–4, ≥5 hours per week), last method of contraception (hormonal contraception yes versus no), menstrual cycle length (<22, 22–35, ≥36 days), intercourse frequency (<1, 1, 2–3, ≥4 times per week), PSS-10 score (<10, 10–19, 20–29, ≥30), doing something to improve chances of contraception (yes versus no),29 history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (yes versus no), depressive symptoms (MDI score: none/low [2920], mild [20–24], moderate [25–29], severe [≥30]),30 sleep duration (<5, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, ≥10 hours per night), employment status (currently employed: yes versus no), job hours (hours worked per week), and diet quality (Healthy Eating Index score).31, 32

We assessed the shape of the curves relating income and education with fecundability using restricted cubic splines.37 We modeled income and educational attainment as linear variables. For income, we used the midpoints of the categorical data and assigned an income of $7,499.50 to the smallest income category (<$15,000) and $225,000 to the largest income category (≥$200,000). For education, we assigned 12 years of education to women reporting a high school degree or equivalent, 14 years to women reporting some college, 16 years to women reporting a college degree, and 18 years to women reporting a graduate degree.

We stratified the results by age at baseline (<30 vs. ≥30 years) to examine whether associations were stronger among older women, for whom fertility is naturally declining. We also restricted the cohort to women with <3 cycles of attempt time at study entry, among whom behaviors (e.g., marijuana use, alcohol intake) would have been less likely to change in response to delayed TTP,38 to reduce the potential for confounder misclassification as a result of change over time. Additionally, we performed secondary analyses restricted to US women, to account for different social welfare benefits and economic policies between the US and Canada. In the education analysis, we considered the joint effect of education of male and female partners (both partners <16 years; female <16 years, male ≥16 years; female ≥16 years, male <16 years; and both partners ≥16 years).

We performed multiple imputation to calculate missing exposure, outcome, and covariate data. For the 1,310 (15.1%) women who did not complete any follow-up questionnaires, we assigned one cycle of follow-up and imputed their pregnancy status at that cycle (pregnant vs. not pregnant). We included over 120 demographic, lifestyle, behavioral, and reproductive variables in the prediction model to create five imputed data sets. The prevalence of missing exposure or covariate data ranged from 0% (e.g., education, age) to 3.4% (household income).

Rates of attrition varied by income and education. Loss to follow-up decreased with increasing education and income. We examined reason for end of follow-up (viable pregnancy, pregnancy loss, initiation of infertility treatment, censored at 12 cycles, stopped attempting pregnancy, lost to follow-up after completing at least one follow-up questionnaire, lost to follow-up without completing at least one follow-up questionnaire, or still participating) according to income and education.. Additionally, we used inverse probability weights to correct for differential attrition.39, 40 We used two pooled logistic regression models, one with baseline and time-varying behavioral, health, and demographic variables, and one with only baseline variables, to predict the probability of study continuation at each follow-up and to compute stabilized weights inversely proportional to the probability of continuation. Women with a low probability of continuation received larger weights to correct for attrition. We applied the stabilized weights to the unadjusted models and adjusted Model 1. Analyses were conducted using SAS software (Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Overall, 8,654 women contributed 33,087 cycles and 5,103 pregnancies during follow-up (Table 1). The percentage lost to follow-up was higher among women with lower income (<$50,000: 33.6%; ≥$150,000: 10.5%) and lower educational attainment (≤12 years: 48.2%; ≥17 years: 11.2%). Approximately 38% of women had ≥17 years of education (corresponding to a graduate degree), and 5% had ≤12 years of education (high school degree or less). Twenty percent had annual household incomes <$50,000 and 15% had annual household incomes ≥$150,000.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of pregnancy planners by educational attainment and household income, PRESTO (N=8,654), North America, 2013–2019

| Education (years) |

Income ($) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤12 | 13–15 | 16 | ≥17 | <50K | 50K–99K | 100–149K | ≥150K | |

| Number of Participants N (%) | 464 (5.4) | 1,969 (22.8) | 2,974 (34.4) | 3,247 (37.5) | 1,779 (20.6) | 3,333 (38.5) | 2,219 (25.6) | 1,323 (15.3) |

| Age (years), mean | 28.3 | 28.8 | 29.5 | 31.0 | 28.2 | 29.5 | 30.6 | 31.8 |

| Partner age (years), mean | 32.5 | 31.8 | 31.8 | 31.9 | 31.5 | 31.7 | 32.1 | 32.8 |

| Married, % | 64.8 | 81.8 | 93.2 | 95.4 | 76.2 | 91.1 | 94.8 | 96.5 |

| Non-Hispanic White, % | 73.6 | 80.3 | 86.0 | 86.7 | 75.8 | 85.2 | 88.0 | 87.1 |

| Annual household income <$50K | 67.2 | 37.7 | 14.2 | 8.7 | ||||

| Number of individuals in household, mean | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| ≥16 years education, % | 38.9 | 70.6 | 88.2 | 92.1 | ||||

| Male partner ≥16 years education, % | 13.0 | 24.9 | 57.9 | 74.2 | 28.0 | 48.8 | 65.8 | 83.4 |

| Mother ≥16 years education, % | 17.1 | 24.5 | 40.3 | 55.2 | 30.2 | 38.0 | 46.0 | 54.8 |

| Father ≥16 years education, % | 12.1 | 23.3 | 41.6 | 56.9 | 28.8 | 38.5 | 47.1 | 59.1 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean | 31.9 | 30.8 | 27.6 | 26.3 | 31.2 | 28.6 | 26.5 | 25.0 |

| Physical activity (MET-hrs/wk), mean | 30.5 | 29.6 | 33.5 | 36.7 | 29.7 | 32.4 | 35.1 | 39.1 |

| Ever smoker, % | 54.6 | 42.2 | 21.6 | 14.2 | 39.3 | 26.8 | 18.6 | 14.2 |

| Current smoker, % | 27.7 | 13.8 | 4.5 | 1.4 | 18.2 | 5.7 | 2.7 | 1.7 |

| Alcohol (drinks per week), mean | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 4.0 |

| Pregnancy attempt time at study entry (cycles), mean | 3.0 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Doing something to improve chances of conceiving, % | 72.7 | 75.3 | 76.4 | 77.2 | 71.3 | 76.3 | 78.2 | 78.6 |

| Intercourse frequency <1 time/week, % | 18.9 | 19.7 | 21.7 | 21.2 | 20.5 | 20.2 | 21.9 | 22.2 |

| Intercourse frequency ≥4 times/week, % | 30.1 | 22.3 | 14.2 | 13.5 | 26.1 | 16.1 | 13.5 | 10.9 |

| History of infertility, % | 31.4 | 16.0 | 6.7 | 3.6 | 19.6 | 8.7 | 4.5 | 2.9 |

| History of any STI, % | 27.6 | 30.6 | 24.4 | 20.2 | 27.3 | 25.0 | 22.5 | 21.8 |

| Parous, % | 60.1 | 48.1 | 31.3 | 22.5 | 48.3 | 35.7 | 25.2 | 22.0 |

| Gravid, % | 76.7 | 68.1 | 49.4 | 38.8 | 65.9 | 53.4 | 42.4 | 39.6 |

| Last contraceptive method hormonal, % | 39.5 | 39.4 | 37.8 | 38.4 | 38.9 | 36.8 | 40.3 | 38.0 |

| PSS-10 score, mean | 19.1 | 17.4 | 16.0 | 15.4 | 18.1 | 16.4 | 15.4 | 14.8 |

| MDI severity score, mean | 16.9 | 13.3 | 10.6 | 8.9 | 14.6 | 11.0 | 9.3 | 8.4 |

| HEI score, mean | 54.1 | 59.7 | 65.2 | 67.8 | 58.3 | 63.8 | 67.1 | 69.3 |

| Currently employed, % | 62.5 | 75.7 | 87.0 | 91.3 | 66.0 | 86.4 | 91.9 | 94.1 |

| Hours worked per week, mean | 34.0 | 36.3 | 37.7 | 39.3 | 33.2 | 37.9 | 39.4 | 40.9 |

| Less than 7 hours sleep per night, % | 40.1 | 36.5 | 25.3 | 17.0 | 37.1 | 26.7 | 19.9 | 17.3 |

All characteristics except for age are age-standardized to the cohort at baseline.

BMI=body mass index, MET= metabolic equivalent, STI= sexually transmitted infection, PSS=Perceived Stress Scale; MDI=Major Depression Inventory; HEI=Healthy Eating Index.

We observed similar patterns in demographic characteristics for categories of income and education (Table 1). Education and income were positively associated with one another and with other SES measures, including parental education, male partner education, and employment status. Education and income both increased with increasing age, percentage non-Hispanic White, hours worked per week, sleep duration, and HEI score, but only income increased with increasing physical activity. Greater education was associated with shorter mean attempt time at study entry. Both education and income decreased with increasing BMI, ever smoking, infertility history, parity, gravidity, MDI score, intercourse frequency and PSS-10 score.

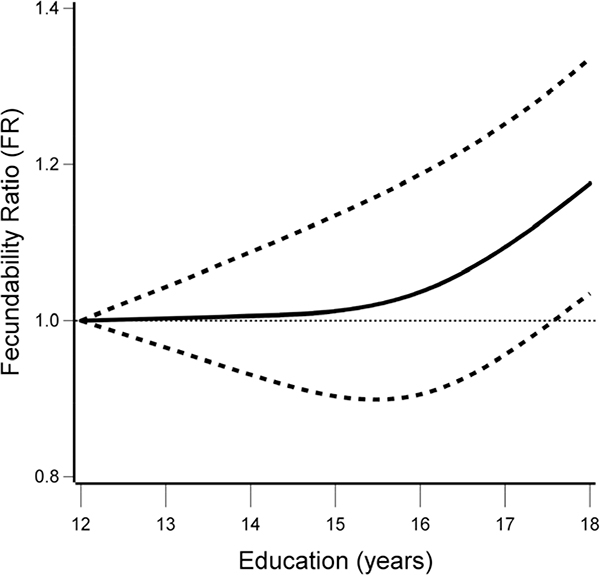

We found a modest positive association between education and fecundability (Table 2). In the minimally-adjusted Model 1, compared with women with graduate degrees, fecundability was lower for women with a high school degree or less (FR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.76–1.08), some college (FR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.78–0.91) or a college degree (FR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.84–0.95). Results did not change appreciably when adjusting for potential confounders and mediators (Model 2). In bivariate analyses, income, BMI, and male partner educational attainment produced the largest changes in effect estimates from unadjusted to fully-adjusted models. Associations between education and fecundability were attenuated among women aged <30 years, and did not vary appreciably based on attempt time at study entry or country of residence. Couples in whom both members had ≤12 years of education had reduced fecundability compared with couples in whom both members had ≥16 years of education (FR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.79–0.94). The restricted cubic spline analysis were consistent with the categorical results (Figure 1); we observed a positive linear association between education and fecundability.

Table 2.

Educational attainment and fecundability, overall and stratified by age at baseline, cycles of pregnancy attempt time at study entry, and nationality (n=8,654)

| No. of Cycles | No. of Pregnancies | Unadjusted FR (95% CI) | Adjusted FR (95% CI)a | Adjusted FR (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational attainment (years) | |||||

| ≤12 | 1,473 | 185 | 0.83 (0.70–0.98) | 0.90 (0.76–1.08) | 0.94 (0.78–1.12) |

| 13–15 | 7,524 | 969 | 0.80 (0.75–0.86) | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) | 0.87 (0.80–0.95) |

| 16 | 11,749 | 1,781 | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) | 0.89 (0.84–0.95) | 0.91 (0.86–0.97) |

| ≥17 | 12,341 | 2,168 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Age <30 years (n=4,251) | |||||

| ≤12 | 937 | 129 | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) | 0.97 (0.79–1.19) | 1.02 (0.82–1.27) |

| 13–15 | 4,429 | 610 | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.88 (0.79–0.99) | 0.91 (0.81–1.03) |

| 16 | 5,911 | 980 | 0.89 (0.82–0.97) | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) |

| ≥17 | 4,254 | 818 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Age ≥30 years (n=4,403) | |||||

| ≤12 | 536 | 56 | 0.76 (0.58–1.01) | 0.90 (0.68–1.20) | 0.82 (0.61–1.09) |

| 13–15 | 3,095 | 359 | 0.78 (0.70–0.87) | 0.89 (0.79–1.00) | 0.85 (0.75–0.96) |

| 16 | 5,838 | 801 | 0.88 (0.81–0.96) | 0.90 (0.82–0.98) | 0.90 (0.82–0.98) |

| ≥17 | 8,087 | 1,350 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| <3 cycles (n=5,689) | |||||

| ≤12 | 780 | 102 | 0.75 (0.62–0.91) | 0.83 (0.68–1.02) | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) |

| 13–15 | 4,571 | 647 | 0.80 (0.73–0.87) | 0.84 (0.76–0.93) | 0.87 (0.79–0.97) |

| 16 | 8,078 | 1,288 | 0.88 (0.83–0.94) | 0.87 (0.81–0.93) | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) |

| ≥17 | 8,814 | 1,662 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| US women (n=7,247) | |||||

| ≤12 | 1,212 | 154 | 0.83 (0.69–1.00) | 0.93 (0.76–1.13) | 0.91 (0.75–1.11) |

| 13–15 | 6,166 | 762 | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) | 0.86 (0.78–0.94) | 0.85 (0.77–0.93) |

| 16 | 9,528 | 1,398 | 0.90 (0.84–0.96) | 0.90 (0.84–0.97) | 0.90 (0.84–0.97) |

| ≥17 | 10,941 | 1,898 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

FR=fecundability ratio, CI=confidence interval.

Model 1 adjusted for age, male partner education, race/ethnicity, and income. .

Model 2 adjusted for variables in model A and marital status, BMI, smoking, physical activity, cycle length, intercourse frequency, last method of contraception, history of sexually transmitted infection, doing something to improve chances of pregnancy, PSS score, MDI score, sleep duration, employment status, hours worked per week, and Healthy Eating Index score.

Figure 1. Restricted cubic splinea and 95% CI showing the association between educational attainment and fecundability, with knots at 10%, 50%, and 90%, PRESTO, North America, 2013–2019.

aSpline adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, income, BMI, smoking, physical activity, male partner education, last method of contraception, cycle length, intercourse frequency, history of sexually transmitted infection, doing something to improve chances of pregnancy, PSS score, MDI score, sleep duration, employment status, hours worked per week, and Healthy Eating Index score.

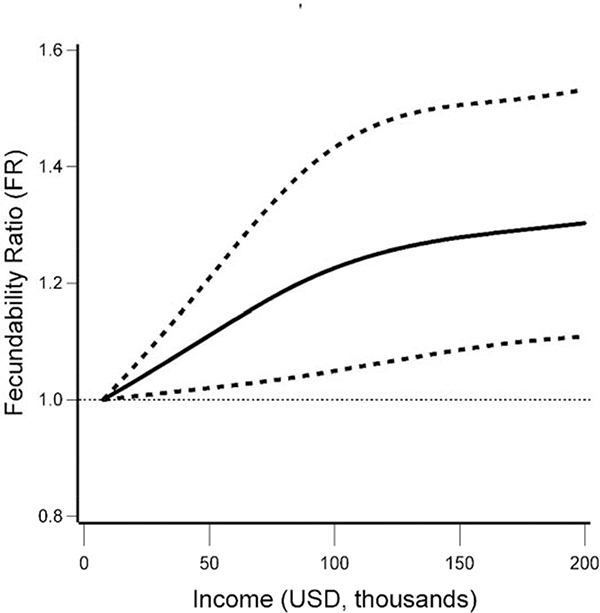

Compared with household incomes ≥$150,000, FRs for household incomes <$50,000, $50,000-$99,999, and $100,000-$149,999 were 0.91 (95% CI: 0.83–1.01), 0.99 (95% CI: 0.92–1.07), and 1.09 (95% CI: 1.01–1.18), respectively (Table 3). In bivariate analyses, educational attainment, male partner educational attainment, BMI, and HEI score produced the largest changes in effect estimates from unadjusted to fully-adjusted models. Among women ≥30 years, there was a stronger reduction in fecundability associated with the lowest income category compared with the highest income category (FR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.76–1.03). Associations between income and fecundability did not vary markedly by attempt time at study entry or by country of residence. The restricted cubic spline analysis supported the categorical results. Women in the lowest income category had the lowest fecundability, and there was a positive linear association between fecundability and income, until incomes of approximately $100,000, at which point additional increases in fecundability were minimal (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Annual household income and fecundability, overall and stratified by age at baseline, cycles of pregnancy attempt time at study entry, and nationality (n=8,654)

| No. of cycles | No. of Pregnancies | Unadjusted FR (95% CI) | Adjusted FR (95% CI)a | Adjusted FR (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income (USD) | |||||

| <50,000 | 6,529 | 840 | 0.88 (0.80–0.96) | 0.91 (0.83–1.01) | 0.95 (0.86–1.06) |

| 50,000–99,000 | 13,068 | 1,970 | 0.97 (0.90–1.05) | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) |

| 100,000–149,000 | 8,148 | 1,432 | 1.09 (1.01–1.18) | 1.09 (1.01–1.18) | 1.10 (1.02–1.19) |

| ≥150,000 | 5,342 | 861 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Age <30 years (n=4,251) | |||||

| <50,000 | 4,182 | 596 | 0.93 (0.81–1.07) | 1.10 (0.95–1.28) | 1.12 (0.96–1.31) |

| 50,000–99,000 | 6,727 | 1,095 | 1.01 (0.89–1.16) | 1.12 (0.98–1.29) | 1.12 (0.98–1.29) |

| 100,000–149,000 | 3,232 | 616 | 1.16 (1.01–1.33) | 1.20 (1.05–1.38) | 1.20 (1.04–1.38) |

| ≥150,000 | 1,390 | 230 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Age ≥30 years (n=4,403) | |||||

| <50,000 | 2,347 | 244 | 0.76 (0.65–0.88) | 0.88 (0.76–1.03) | 0.86 (0.73–1.01) |

| 50,000–99,000 | 6,341 | 875 | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) | 0.98 (0.89–1.09) | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) |

| 100,000–149,000 | 4,916 | 816 | 1.04 (0.95–1.15) | 1.05 (0.95–1.16) | 1.05 (0.95–1.16) |

| ≥150,000 | 3,952 | 631 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| <3 cycles (n=5,689) | |||||

| <50,000 | 3,779 | 525 | 0.86 (0.77–0.96) | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | 0.95 (0.84–1.08) |

| 50,000–99,000 | 8,962 | 1,438 | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 1.03 (0.93–1.13) |

| 100,000–149,000 | 5,585 | 1,084 | 1.13 (1.04–1.24) | 1.13 (1.03–1.24) | 1.14 (1.05–1.25) |

| ≥150,000 | 3,917 | 652 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| US women (n=7,247) | |||||

| <50,000 | 5,643 | 718 | 0.88 (0.79–0.97) | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) |

| 50,000–99,000 | 10,814 | 1,597 | 0.97 (0.89–1.05) | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | 1.01 (0.92–1.10) |

| 100,000–149,000 | 6,712 | 1,144 | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 1.08 (0.99–1.17) | 1.08 (0.99–1.18) |

| ≥150,000 | 4,678 | 753 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

FR=fecundability ratio, CI=confidence interval, USD=United States dollar.

Model 1 adjusted for age, education, male partner education, and race/ethnicity.

Model 2 adjusted for variables in model A and marital status, BMI, smoking, physical activity, cycle length, intercourse frequency, last method of contraception, history of sexually transmitted infection, doing something to improve chances of pregnancy, PSS score, MDI score, sleep duration, employment status, hours worked per week, and Healthy Eating Index score.

Figure 2. Restricted cubic splinea and 95% CI showing the association between household income and fecundability, with knots at 10%, 50%, and 90%, PRESTO, North America, 2013–2019.

aSpline adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI, smoking, physical activity, male partner education, last method of contraception, cycle length, intercourse frequency, history of sexually transmitted infection, doing something to improve chances of pregnancy, PSS score, MDI score, sleep duration, employment status, hours worked per week, and Healthy Eating Index score.

Reasons for censoring varied by income and education. Use of infertility treatment and viable pregnancies were lowest among women with lower income and education. Pregnancy loss increased with increasing education and income (Supplemental Table 1). Though attrition was associated with income and education, correcting for attrition using stabilized inverse probability of continuation weights did not appreciably change the results for unadjusted models or Model 1 (Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of North American pregnancy planners, annual household income was positively associated with fecundability up to about $100,000, at which point the effect plateaued. In addition, women with less than 17 years of education had small reductions in fecundability. Control for additional confounders and mediators did not appreciably change these results. Associations for income and education with fecundability were slightly stronger among women aged ≥30 years in the lowest income and education categories.

Among participants aged <30 years, results for education and income were attenuated. Differences in income and education may have a smaller impact at younger ages, when fertility is naturally higher.

The mechanisms underlying socioeconomic-based disparities in fecundability are unclear and may comprise a combination of access to and utilization of resources, health literacy, and lifestyle factors. We observed that other measures of SES (e.g., in analyses of education, income, and male partner education) and lifestyle factors (BMI, diet) were important contributors to the observed changes between unadjusted and adjusted models in both analyses. This suggests mechanisms are likely complex among correlated factors.

To our knowledge, no prospective study has examined the association between SES and fecundability as a measure of fecundity. Our results agree with NSFG data indicating an inverse association between education and impaired fecundity.9 In addition, our findings for education, but not income, are consistent with an analysis of NSFG data that used the current-duration approach to define infertility.10 Inconsistencies between studies could reflect differences in study designs, study populations, definitions of infertility and impaired fecundity, and control for potential confounders.

While our study accounted for several potential confounders and mediators, we were unable to examine all possible mechanisms, including the effects of chronic psychosocial stress due to lower socioeconomic status or lifetime access to healthcare on fecundability. Socioeconomic inequities across the fertility spectrum deserve attention, especially if there are modifiable downstream factors to improve reproductive potential among couples trying to conceive. For example, in our study, women with lower SES had longer pregnancy attempt times at study entry and were less likely to be censored due to either a viable pregnancy or the initiation of infertility treatment during follow-up.

There are several limitations to this study. Small numbers of women with lower educational attainment reduced our ability to precisely estimate effects in these subgroups. Longer pregnancy attempt times at enrollment among women with lower SES could have introduced selection bias if participation by subfertile women varied by exposure. Restricting to women trying <3 cycles at baseline, which would reduce potential for selection bias, yielded associations that were similar (income) or stronger (education), indicating that, if present, such bias may be attenuating our results. Selection bias due to loss to follow-up is also possible. Loss to follow-up was higher among women with lower income and lower educational attainment. If women lost to follow-up were less likely to conceive during the study period, this would result in an upward bias. In contrast, women who conceive quickly may have elected to discontinue participating in the study, which would result in a downward bias. However, we accounted for this using inverse probability weighting methods, and the effect of the bias was minimal.

We used a wide range of variables to multiply-impute pregnancy status for women lost to follow-up. However, we may have inadvertently omitted variables predictive of pregnancy status in our multiple-imputation model, which would result in an unpredictable bias. In addition, exposure variables were measured by self-report, introducing potential for misclassification. Furthermore, while educational attainment and annual household income are commonly-used measures of particular dimensions of SES, this operationalization is limited in breadth. For example, household income does not measure wealth (e.g., home ownership, family inheritance) nor access to societal resources, such as healthier neighborhoods and foods. For the sake of simplicity, we did not adjust annual household income by number of people supported by that income by using per capita income or an equivalence scale,41 although household size decreased only slightly with increasing income and education. Additionally, educational attainment does not measure quality of education, which may contribute to potential mechanisms of association. Nevertheless, due to the prospective study design, such misclassification is unlikely to be differential (i.e., related to fecundability), and is expected to bias FRs towards the null in the extremes of the ordinal categories. Misclassification of fecundability was possible. The calculation of conception cycle was dependent on self-reported LMP and average cycle length. If accurate reporting of these factors differed by exposure, the resulting bias would be unpredictable. Though we controlled for several confounders, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Unmeasured factors, such as potential genetic factors, may predict both exposure and outcome.

PRESTO is an internet-based convenience sample of female pregnancy planners and is not representative of all women who conceive. About 50% of pregnancies in the U.S. are unintended.42 Because pregnancy planning is a requirement for cohort inclusion, if pregnancy planning is inversely associated with SES, and pregnancy planning is inversely related to fecundability, our results may be biased upward. Though participation in an internet-based study may vary by demographic or lifestyle characteristics, measures of association are not necessarily biased due to self-selection.28, 43, 44 Nevertheless, a selection bias could exist, though it is difficult to predict the direction and magnitude of such bias, considering women who do not plan their pregnancies and women who choose not to participate likely have varying underlying fecundability. This potential selection bias could explain some of the observed differences in results between our study and previous studies.

PRESTO differs from previous studies in that participants were enrolled before conception and data were collected prospectively, reducing the degree of selection bias and differential exposure misclassification, respectively. The study population represents the full spectrum of fertility, from those who conceive quickly to those who take ≥12 months to conceive. We additionally collected information on a wide range of potential biomedical, lifestyle, and behavioral confounders.

Overall, these results indicate that higher income and educational attainment are associated with modestly improved fecundability, and these associations appear to be slightly stronger among women over age 30, when fertility is naturally declining. Our data indicate that fertility is yet another aspect of health that may be related to socioeconomic status.

Supplementary Material

Funding Information and Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Eunice K. Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD086742, R21-HD072326, and T32-HD052458). We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of PRESTO participants and staff. We thank Catherine Duarte, MSc for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report--United States, 2013. MMRW 2013; 62: 1–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2015 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report and 5th Anniversary Update on the National Quality Strategy Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2016. AHRQ Pub. No. 16–0015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkleby MA, Cubbin C. Influence of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on mortality among non-Hispanic Black, Mexican-American, and white women and men in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003; 57:444–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan G, Keil J. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation. 1993; 88:1973–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lasser KE, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Access to care, health status, and health disparities in the United States and Canada: results of a cross-national population-based survey. Am J Public Health. 2006; 96:1300–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Link BG, Phelan J. Social Conditions As Fundamental Causes of Disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson MH, Chin HB, Mertens AC, Spencer JB, Fothergill A, Howards PP. “Research on Infertility: Definition Makes a Difference” Revisited. Am J Epidemiol. 2018; 187:337–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marchbanks P, Peterson H, Rubin G, Wingo P. Research on infertility: Definition makes a difference. Am J Epidemiol. 1989; 130:259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra A, Copen C, Stephen E. Infertility and impaired fecundity in the United States, 1982–2010: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth. In: Services HaH, editor. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thoma ME, McLain AC, Louis JF, King RB, Trumble AC, Sundaram R, et al. Prevalence of infertility in the United States as estimated by the current duration approach and a traditional constructed approach. Fertil Steril. 2013; 99:1324–31 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive M. Disparities in access to effective treatment for infertility in the United States: an Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015; 104:1104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macaluso M, Wright-Schnapp TJ, Chandra A, Johnson R, Satterwhite CL, Pulver A, et al. A public health focus on infertility prevention, detection, and management. Fertil Steril. 2010; 93:16 e1–0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health. 2014; 104 Suppl 1:S43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016; 374:843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dye TD, Wojtowycz MA, Aubry RH, Quade J, Kilburn H. Unintended pregnancy and breast-feeding behavior. American Journal of Public Health. 1997; 87:1709–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellerstedt WL, Pirie PL, Lando HA, Curry SJ, McBride CM, Grothaus LC, et al. Differences in preconceptional and prenatal behaviors in women with intended and unintended pregnancies. American Journal of Public Health. 1998; 88:663–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kost K, Lindberg L. Pregnancy intentions, maternal behaviors, and infant health: investigating relationships with new measures and propensity score analysis. Demography. 2015; 52:83–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maddow-Zimet I, Lindberg L, Kost K, Lincoln A. Are Pregnancy Intentions Associated with Transitions Into and Out of Marriage? Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2016; 48:35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glymour M, Avendano M, Kawachi I. Socioeconomic Status and Health In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, Glymour M, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York, Ny: Oxford Press; 2014. p. 17–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wellons MF, Lewis CE, Schwartz SM, Gunderson EP, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, et al. Racial differences in self-reported infertility and risk factors for infertility in a cohort of black and white women: the CARDIA Women’s Study. Fertil Steril. 2008; 90:1640–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler LM, Craig BM, Plosker SM, Reed DR, Quinn GP. Infertility evaluation and treatment among women in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2013; 100:1025–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luderer U, Li T, Fine JP, Hamman RF, Stanford JB, Baker D. Transitions in pregnancy planning in women recruited for a large prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2017; 32:1325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pulley L, Klerman L, Tang H, Baker B. The Extent of Pregnancy Mistiming and Its Association With Maternal Characteristics and Behaviors and Pregnancy Outcomes. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002; 34:206–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxson P, Miranda ML. Pregnancy intention, demographic differences, and psychosocial health. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011; 20:1215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly-Weeder S, Cox CL. The Impact of Lifestyle Risk Factors on Female Infertility. Women & Health. 2007; 44:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Augood C, Duckitt K, Templeton A. Smoking and female infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 1999; 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassan MA, Killick SR. Negative lifestyle is associated with a significant reduction in fecundity. Fertil Steril. 2004; 81:384–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wise LA, Rothman KJ, Mikkelsen EM, Stanford JB, Wesselink AK, McKinnon C, et al. Design and Conduct of an Internet-Based Preconception Cohort Study in North America: Pregnancy Study Online. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015; 29:360–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983; 24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bech P Quality of life instruments in depression. Eur Psychiatry. 1997; 12:194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guenther P, Kirkpatrick S, Reedy J, al. e. The Healthy Eating Index-2010 is a valid and reliable measure of diet quality according to the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. J Nutrition. 2014; 144:399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy E, Ohis J, Carlson S, Fleming K. The Healthy Eating Index: design and applications. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995; 95:1103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972; 34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Therneau T, Grambsch P. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Ye A, Platt RW. Accuracy loss due to selection bias in cohort studies with left truncation. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013; 27:491–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howards P, Hertz-Picciotto I, Poole C. Conditions for bias from differential left truncation. Am J Epidemiol. 2007; 165:444–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989; 8:551–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wise LA, Wesselink AK, Hatch EE, Weuve J, Murray EJ, Wang TR, et al. Changes in behavior with increasing pregnancy attempt time: a prospective cohort study. Epidemiology. 2020; Publish Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weuve J, Tchetgen Tchetgen Ej Fau - Glymour MM, Glymour Mm Fau - Beck TL, Beck Tl Fau - Aggarwal NT, Aggarwal Nt Fau - Wilson RS, Wilson Rs Fau - Evans DA, et al. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howe CJ, Cole Sr Fau - Lau B, Lau B Fau - Napravnik S, Napravnik S Fau - Eron JJ Jr., Eron JJ Jr. Selection Bias Due to Loss to Follow Up in Cohort Studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garner T, Ruiz-Castillo J, Sastre M. The Influence of Demographics and HouseholdSpecific Price Indices on Consumption-Based Inequality and Welfare: A Comparison of Spain and the United States. Southern Economic Journal. 2003; 70:22–48. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health. 2014; 104:S43–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK, Skjaerven R, Melve KK, Schreuder P, et al. Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009; 23:597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatch EE, Hahn KA, Wise LA, Mikkelsen EM, Kumar R, Fox MP, et al. Evaluation of Selection Bias in an Internet-based Study of Pregnancy Planners. Epidemiology. 2016; 27:98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.