Abstract

Background:

Respectful maternity care is a rightful expectation of women. However, disrespectful maternity care is prevalent in various settings. Therefore, a systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to identify various forms of ill-treatment, determinants, and pooled prevalence of disrespectful maternity care in India.

Methods:

A systematic review was performed in various databases. After quality assessment, seven studies were included. Pooled prevalence was estimated using the inverse variance method and the random-effects model using Review Manager Software.

Results:

Individual study prevalence ranged from 20.9% to 100%. The overall pooled prevalence of disrespectful maternity care was 71.31% (95% CI 39.84–102.78). Pooled prevalence in community-based studies was 77.32% (95% CI 56.71–97.93), which was higher as compared to studies conducted in health facilities, this being 65.38% (95% CI 15.76–115.01). The highest reported form of ill-treatment was non-consent (49.84%), verbal abuse (25.75%) followed by threats (23.25%), physical abuse (16.96%), and discrimination (14.79%). Besides, other factors identified included lack of dignity, delivery by unqualified personnel, lack of privacy, demand for informal payments, and lack of basic infrastructure, hygiene, and sanitation. The determinants identified for disrespect and abuse were sociocultural factors including age, socioeconomic status, caste, parity, women autonomy, empowerment, comorbidities, and environmental factors including infrastructural issues, overcrowding, ill-equipped health facilities, supply constraints, and healthcare access.

Results:

Individual study prevalence ranged from 20.9% to 100%. The overall pooled prevalence of disrespectful maternity care was 71.31% (95% CI 39.84–102.78). Pooled prevalence in community-based studies was 77.32% (95% CI 56.71–97.93), which was higher as compared to studies conducted in health facilities, this being 65.38% (95% CI 15.76–115.01). The highest reported form of ill-treatment was non-consent (49.84%), verbal abuse (25.75%) followed by threats (23.25%), physical abuse (16.96%), and discrimination (14.79%). Besides, other factors identified included lack of dignity, delivery by unqualified personnel, lack of privacy, demand for informal payments, and lack of basic infrastructure, hygiene, and sanitation. The determinants identified for disrespect and abuse were sociocultural factors including age, socioeconomic status, caste, parity, women autonomy, empowerment, comorbidities, and environmental factors including infrastructural issues, overcrowding, ill-equipped health facilities, supply constraints, and healthcare access.

Conclusion:

The high prevalence of disrespectful maternity care indicates an urgent need to improve maternity care in India by making it more respectful, dignified, and women-centered. Interventions, policies, and programs should be implemented that will protect the fundamental rights of women.

KEY WORDS: abuse, childbirth, disrespect, India, meta-wanalysis

Introduction

Respectful maternity care (RMC) is a rightful expectation of every woman. On the contrary, problems such as disrespect, abuse, ill-treatment, demand for informal payments, infrastructural issues such as lack of water supply, sanitation, electricity, and crowded rooms are prevalent globally. Another problem highlighted is that women either receive services “too much and too soon or too little and too late.”[1] Disrespectful care is therefore a topic of public health concern and has an effect on utilization of services, affects the progress of the country in terms of healthcare, and affects the mothers physically as well as psychologically. To provide RMC, the White Ribbon Alliance, released the first charter on components of RMC including “respect for women's autonomy, dignity, empathy, privacy, confidentiality, feelings, choices, and preferences, including companionship during maternity care and continuous care during labor and childbirth and also prevention of harm and ill-treatment.”[2] Therefore, the objectives were to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify the various forms of ill-treatment, to study the determinants and to estimate the prevalence of disrespectful maternity care in India.

Methods

Search strategy

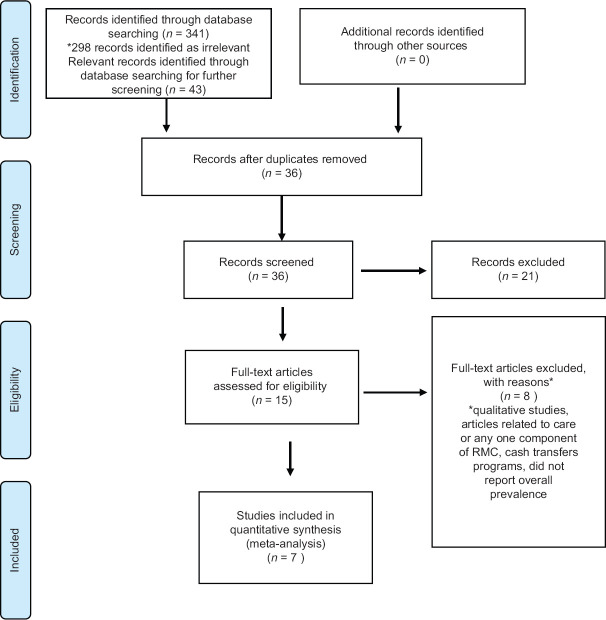

This systematic review included published studies on disrespect and abuse during pregnancy and childbirth in India. A literature search was performed in the databases including PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus in November and December 2018 and updated in July 2019. The search was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Figure 1].[3] The terms used were free text terms and terms including “RMC in India” or “Maternity Care in India” or “Respectful care in India” or “Intrapartum care” or “Care during labor and delivery in India” or “Postpartum care'” or “Quality of care” or “Experience of care” or “Abuse and disrespect during pregnancy in India” or “Mistreatment during pregnancy in India” or “Ill-treatment” or “Disrespect during childbirth” or “Prevalence of disrespect and abuse” or “Disrespect in India.” These terms were used in various combinations (Boolean operators) and filters were applied. Medical Subject Headings were also used. There was no restriction on the date of publication. The reference lists of the relevant studies were also reviewed to identify other studies. Searches of the studies were done by Ansari.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart: Selection of studies

Study selection

Studies done in India focusing on the components of respectful maternity care and those which gave description of study participants, sample size and percentage or number of disrespect, abuse, or mistreatment during childbirth and those published in English were included in the review. Qualitative studies, or those focusing only on any one component of RMC were excluded. Screening and inclusion of the studies for systematic review and meta-anaylsis was agreed by both authors. All the full text articles were retrieved and 15 full text articles were identified based on literature search. After assessing for eligibility, a total of seven studies were included in this review [Table 1].

Table 1.

Description of respectful maternity care studies

| Author | Year | Place | Study setting | Study design | Number of participants | Age group | Method of data collection | Type of disrespect | Prevalence of disrespect and abuse | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nawab et al.[10] | 2019 | Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh | Community (Rural) | Cross-sectional | 305 | <20->30 | Interviews | Women at 4-6 weeks postpartum | Physical abuse, non-consented care, non-confidential care, discrimination, non-dignified care, abandonment, detention | 84.3% | System based drivers and perception of healthcare providers were not explored. |

| Sharma et al.[6] | 2019 | Kannauj, Kanpur Nagar, Kanpur Dehat, Uttar Pradesh | 26 Public and private Health facilities | Mixed methods | 275 | <20->35 | open-ended questions and observation tool | Women during labor and childbirth | Physical abuse, companion not allowed, verbal abuse, lack of privacy, informal payments, non-consented care | 100% | The study was not specifically looking at ill-treatment as a separate quality of care indicator. Observer bias. Limited sample from the private sector. |

| Bhattacharya 2018 et al.[7] | 2018 | Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh | Community (Rural) | Cross-sectional | 410 | 24.7+/-3.18 | Interviews | Women who delivered at the health facility | Physical abuse, insults, threats, verbal abuse, neglect, non-confidential care, lack of cleanliness | 92.7% | Findings cannot be generalized. Small sample size. |

| Singh et al.[11] | 2018 | New Delhi | 3 hospitals/ Health facilities | Cross-sectional | 63 health professionals observed based on a checklist | - | Observation | The second stage of labor to 2 hours post-delivery | Physical, verbal abuse, non-consented care, con-confidential care, lack of privacy, lack of dignity and respect, discrimination, left without care, detainment, threats | 98% | Small sample size. Presence of the researcher influences the practices performed. |

| Dey et al.[8] | 2017 | Uttar Pradesh | 81 public health facilities | Cross-sectional | 875 | 17-49 | Observations, Interviews | Women delivering in public health facilities interviewed 2-4 weeks post-delivery | Physical abuse, verbal abuse, threats, unavailability of provider, did not answer questions, incomplete information, non-consented care, discrimination, denial of treatment | 77.3% | Findings cannot be generalized. The perception of healthcare providers were not explored. Inter-rater reliability not assessed. In the observational study, causality cannot be established. |

| Raj et al.[9] | 2017 | Uttar Pradesh | 68 public health facilities | Cross-sectional | 2639 | 17-48 | Interviews | Women delivered at the health facility, interviews conducted an average of 4.5 weeks postpartum | Physical abuse, verbal abuse, non-consented care, stigma and discrimination, non-supportive care, denial of treatment | 20.9% | Findings cannot be generalized. Recall bias. It did not include all domains of ill-treatment. Causality cannot be established. |

| Sudhinaraset et al.[12] | 2016 | Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh | Community (38 urban slums) | Mixed methods | 392 quantitative sample, 26 qualitative sample | 18-30 | Survey, focus group discussions | Women with a child under the age of 5, delivered in a health facility | Discrimination. Physical abuse, verbal abuse, threats, lack of information, abandonment, choice of position denied, companion not allowed, informal payment, separation from baby, delivered alone | 54.7% | Not representative. The perception of healthcare providers were not explored. |

Data quality

The quality of the quantitative studies was assessed using Critical Appraisal for a Survey.[4] Assessment included aim, study design, methodology, selection bias, sample representative of the population, sample size, response rate, questionnaire, statistical analysis, confounding factors, and application of findings. The quality of the qualitative studies was assessed using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme[5] and included aim, methodology, recruitment strategy, data collection, ethical issues, data analysis, findings, and value of research. The studies were rated as high, medium, and low by the authors. However, no study was excluded as a result of quality assessment.

Data extraction

Data were extracted based on name of author, year of publication, state or city in which the study was conducted, study setting, study design, sample size, mean age of the study population, method of data collection, type of disrespect or ill-treatment, prevalence of disrespect, and limitations of the respective studies.

Data synthesis and analysis

Components of disrespectful maternity care and the determinants for the same were identified from the studies. Further, data were entered in Review Manager and analyzed for pooled prevalence using inverse variance and random effects model due to the heterogeneity of studies. Data were assessed for heterogeneity using I2 > 95%, and significance at a P value less than 0.05. Sensitivity analysis was also done by location, place of study, and timing of interview.

Results

This review synthesized results from seven studies [Table 1] done in India i.e., from New Delhi and Uttar Pradesh. All these studies have been published during 2016–2019. Five studies were cross sectional studies and two used a mixed methods approach. Of the seven studies conducted, four were hospital/health facility-based and three were community-based studies. One study was conducted in New Delhi while the remaining six were conducted in Uttar Pradesh. The total study population was 4959. The sample size varied from 63 to 2639. Data collection methods included interviews, observations, and focus group discussions. Individual study prevalence ranged from 20.9% to 100%.

Components of disrespectful maternity care identified from the studies

Various forms of ill-treatment were reported in all studies. Physical abuse was reported in all seven studies. This included shouting, slapping, pinching, hitting, and also application of extreme fundal pressure.[6] In addition to this, procedures like episiotomy were performed without anesthesia.[7] Physical abuse (13.4%) was a common abuse reported by Bhattacharya et al.[7] Similar findings were reported in other studies.[8,9,10,11] Verbal abuse was reported from six studies and included use of foul language, scolding, shouting, threatening, and humiliating. It was the most common form of abuse reported in a mixed methods study (28.6%).[12] Study done by Nawab et al.[10] and Dey et al.[8] reported non-consented care as the highest form of ill-treatment. Procedures such as episiotomy and or minor procedures were performed without consent. Another study[6] showed that women were not informed prior to vaginal examination. Two other cross sectional studies[9,11] reported that questions were not responded to, information and explanation of various procedures were not given. Discrimination was observed based on caste and tribe or on the basis of a certain socioeconomic status.[11,12] Discrimination was a common ill-treatment reported in one cross sectional study.[9] Threats such as performing operative procedures, not giving anesthesia, detainment in facilities[6] or withholding treatment were reported.[7] Threats were also reported by Dey et al.[8] Privacy and confidentiality were not provided. There was inappropriate exposure and also curtains or screens were not present.[7,11] Use of dirty clothes, unsterile equipments, and dirty gloves were reported in two studies.[6,11] Examinations were frequent and done by multiple health workers. Besides, syringes were left on the floor. The hospital and labor rooms were unhygienic and unclean.[6,7] Stray animals like dogs and cows were seen in the facility. The labor rooms also had mice. Equipments like autoclave, suction machines were not used and were covered in dust.[6] Women were ignored and even delivered alone,[7,11] and women and newborn were also detained in facilities[6,7] Women were not offered birthing position and were not allowed to be in a position of their choice as reported by studies.[6,11] Demand for informal payments was common in public sector[6] and informal payments were asked for activities that were a part of the job. Moreover, the families were asked to purchase material and equipments that were covered under the health scheme. Demand for informal payments was also reported by Singh et al.[11] Delivery by untrained personnel was more commonly observed in the public sector as compared to the private sector due to staff shortage. Non-presence of the healthcare providers was also observed.[8]

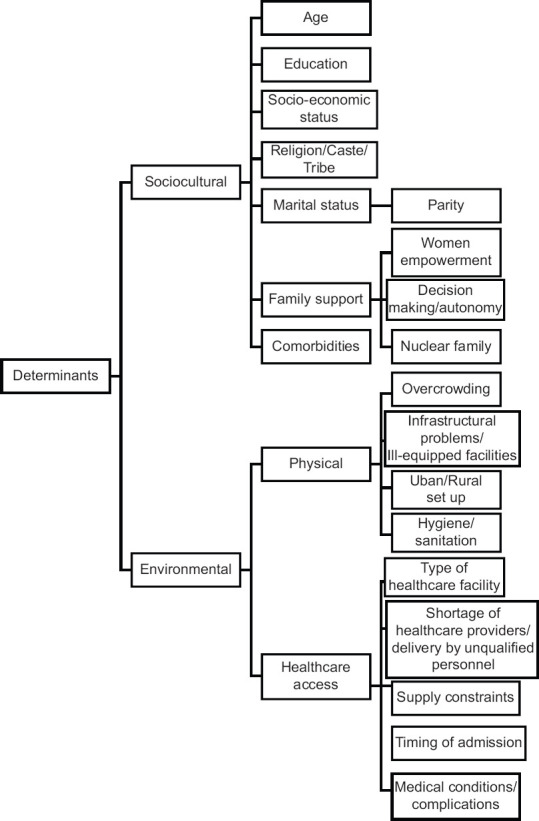

Determinants for disrespect and abuse identified from the studies

Figure 2 highlights the determinants of disrespectful maternity care. Women were not aware of forms of disrespect and abuse, they considered it normal leading to underreporting of the various types of ill-treatment.[10] Besides, in a study by Raj et al.[9], women with lower education were less likely to report complications; however, no study found association between education and ill-treatment. A study found that the odds of disrespect and abuse increased when the decision of place of delivery was by someone other than the woman herself. Study done by Sharma et al.[6] reported that timing of admission to the hospital had an influence on the ill-treatment which was more common during working hours. Admission during weekends also led to ill-treatment. A study done by Nawab et al. found no association between timing of delivery and disrespect.[10] As reported by Nawab et al.[10] women in the public facilities experienced more disrespect and abuse. However, according to another study disrespect and abuse were almost same in public and private facilities.[7] Public facilities were also overcrowded and lacked basic equipments and infrastructure.[6] With respect to birthing position, disrespect for choice was observed in both types of facilities. Physical abuse, non-consented care, and lack of privacy were higher in public sector. In the private sector birth companions were not allowed. Similarly, age of women above 35 years,[8] was found to be associated with ill-treatment. However, in a study conducted by Sudhinaraset et al.[12] and Nawab et al.[10] age was not found to be associated with any forms of ill-treatment. According to a study, women belonging to the lower socioeconomic status experienced ill-treatment.[10] However, another study reported that women belonging to higher wealth quintile reported ill-treatment.[12] Care provided other than doctors or unqualified personnel was a determinant identified for disrespect and abuse.[7,8,9,10] Women belonging to certain castes and tribes, lower caste women experienced discrimination and abuse.[7,8,9,10] Parity was also a reason identified for disrespect and abuse.[8,9] Nuclear family, women who had vaginal delivery[10] presence of complications were also identified as predictors for disrespect and abuse in other studies.[7,8,9]

Figure 2.

Determinants of disrespectful maternity care

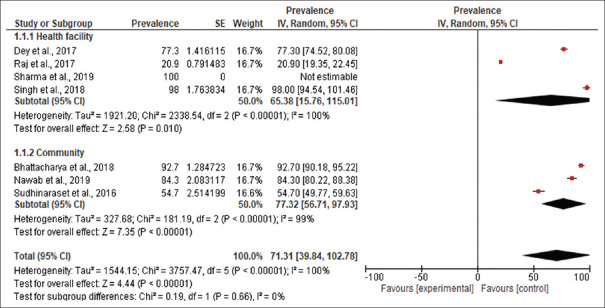

Meta-analysis

Pooled prevalence of disrespectful maternity care

Pooled prevalence of any form of disrespectful maternity care was 71.31% [95% Confidence Interval (CI) 39.84-102.78]. In community-based studies the prevalence was 77.32% (95% CI 56.71–97.93) which was higher as compared to studies conducted in hospitals, this being 65.38% (95% CI 15.76–115.01) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Pooled prevalence of any form of disrespectful maternity care

Prevalence of selected components of disrespectful maternity care

Table 2 gives the pooled prevalence of the most commonly encountered ill-treatment from the included studies. The highest reported forms of ill-treatment were non consent, verbal abuse followed by threats, physical abuse, and discrimination. Pooled prevalence of physical abuse from seven studies was 16.96% (95%CI 10.93–23.00) and pooled prevalence of verbal abuse from six studies was 25.75% (95% CI 15.63–35.87). Pooled prevalence of non-consent and discrimination from five studies was 49.84% (95% CI 28.49–71.18) and 14.79% (95% CI 7.82–21.77) respectively. Pooled prevalence of threats from four studies was 23.25% (95% CI 10.65–35.86). Except non-consent all other forms of ill-treatment (verbal abuse, threats, physical abuse and discrimination) were reported to be higher when interview or observations were done at health facilities as compared to studies conducted in the community.

Table 2.

Prevalence of selected components of disrespectful maternity care

| Type of ill-treatment | Hospital studies Prevalence (%), 95% CI | Community studies Prevalence (%), 95% CI | Total Prevalence (%), 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-consent[6,8,9,10,11] | 44.53 (22.22-66.84) | 71.10 (66.01-76.19) | 49.84 (28.49-71.18) |

| Verbal abuse[6,7,8,9,11,12] | 27.11 (15.06-39.16) | 22.87 (11.80-33.95) | 25.75 (15.63-35.87) |

| Threats[7,8,11,12] | 38.91 (-33.42-111.23) | 11.22 (9.03-13.40) | 23.25 (10.65-35.86) |

| Physical abuse[6,7,8,9,10,11,12] | 24.23 (15.36-33.10) | 7.86 (1.26-14.46) | 16.96 (10.93-23.00) |

| Discrimination[8,9,10,11,12] | 19.01 (8.69-29.33) | 10.26 (-2.38-22.90) | 14.79% (7.82-21.77) |

Table 3 gives the sensitivity analysis based on location, place of study, and timing of interview. There was high heterogeneity. Community-based studies gave the highest prevalence of disrespect and abuse. It was also observed that timing of interview and place of study lowered the prevalence estimates. After dropping of extreme values from the dataset, the pooled prevalence estimates [77.36 (63.69–91.03)] were similar to the findings of the community-based studies [77.32 (56.71–97.93)] as well as the total pooled prevalence [71.31 (39.84–102.78)].

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis

| Number of studies | Pooled estimate (95% CI) | I2% | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total[6,7,8,9,10,11,12] | 7 | 71.31 (39.84-102.78) | 100 | <0.00001 |

| Community-based studies[7,10,12] | 3 | 77.32 (56.71-97.93) | 99 | <0.00001 |

| Hospital-based studies[6,8,9,11] | 4 | 65.38 (15.76-115.01) | 100 | <0.00001 |

| After dropping studies that might influence pooled prevalence[7,8,10,12] | 4 | 77.36 (63.69-91.03) | 98 | <0.00001 |

| Studies conducted only in Uttar Pradesh[6,7,8,9,10,12] | 6 | 65.97 (31.78-100.16) | 100 | <0.00001 |

| Interview conducted immediately post-delivery up to 6 weeks post-partum[6,8,9,10,11] | 5 | 70.11 (28.94-111.27) | 100 | <0.00001 |

Discussion

The objectives of this systematic review were to assess the prevalence of disrespectful maternity care in India and to identify the determinants of disrespectful maternity care. Seven studies included in this review indicated that the mothers from different geographical areas, public as well as private hospitals experienced various forms of disrespectful maternity care, and the findings were consistent with the findings of the studies done globally.[13]

The prevalence is almost similar to the prevalence reported in Tanzania (70%).[14] This is higher than that reported from a systematic review of Ethiopia that showed the prevalence to be 49.4%.[15] Countries like Brazil[16] and Mexico[15] also had a low prevalence of disrespect and abuse. However, studies from Sudan,[17] Pakistan,[18,19] and Peru[20] have reported a higher prevalence. The difference in these findings may be due to the methodologies, definitions adopted, and sociocultural factors in different studies.

The components of disrespectful maternity care including non-consent, verbal and physical abuse, threats, and discrimination identified from this review were similar to other studies.[21,22,23,24] As stated by Jha et al.[25] women deliver at government hospitals to reduce the financial burden but in lieu of this they have to compromise on dignity and respect. As a result women are not keen on delivering at health facilities or seek late treatment. Pooled prevalence in community-based studies was higher as compared to studies conducted in hospitals. Similar results have been identified in other studies, probably because women were comfortable in expressing their opinion at home. At health facilities they are under pressure and may feel they will not get good treatment if they report negative findings of the facility.[10] On the other hand, factors such as verbal abuse, threats, physical abuse, and discrimination were reported to be higher in hospital-based studies. This could possibly be influenced because of observation by the researchers and discordance in reporting, as such factors are considered to be normal by the mothers due to lack of awareness or underreporting.

Our findings show that various factors are responsible for disrespectful maternity care including sociocultural factors and environmental factors viz. physical problems such as lack of basic infrastructure, sanitation, hygiene, and overcrowding. Healthcare issues such as shortage of staff, equipments, and trained personnel were reported. These findings were similar to the findings of a qualitative systematic review and a systematic review on evidence-based typology.[21,22]

Studies also show that the birth outcome[9] is better when the mother receives quality care. It is essential to create awareness among the mothers regarding respectful maternity care. It is essential to address factors such as workload on providers, infrastructure at the hospitals so that women get access to good quality care. This can be achieved by regular monitoring and supervision, audits, exit interviews and team support. Delivering respectful maternity care is based on many factors and being multifactorial, it is essential to address all the issues and not just focus on any one.[1]

Taking into consideration the high prevalence of disrespectful maternity care in the country, this systematic review and meta-analysis will serve as an evidence base for designing targeted interventions and for policy and program implementation specifically under the Ayushman Bharat Program, health and wellness centers to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC). The health and wellness centers are set up to provide pregnancy and childbirth services, neonatal and infant services, and reproductive healthcare services.[26] The challenges addressed by this scheme include health infrastructure, resources, quality of services, health financing, and continuum of care. Therefore, majority of the problems identified through the systematic review and meta-analysis could be addressed by the implementation of the Ayushman Bharat Program focusing on RMC. Achievement of UHC requires a holistic approach and is not possible without providing quality care and meeting the requirements of RMC. This, in turn, will help in achieving the Sustainable Developmental Goals, goal number three and ten i.e., good health and well-being and reduced inequalities.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis from India to report the prevalence of disrespectful maternity care. Being a systematic review it helped capture data from all sections including public, private health facilities, and communities. A limitation of the study is that all searches were conducted by only one author. Data on care of mothers who had to terminate pregnancy due to anomalies or other problems were not available. Besides, the type of facilities (primary, secondary or tertiary) were not mentioned in the studies. Therefore, the data cannot be differentiated based on level of facilities. It is also important to note that the studies included in the review are focusing on ill-treatment in the form of disrespect and abuse faced by mothers during childbirth. The other studies not included in the review have not reported the prevalence of disrespect and abuse. Among the included studies, commenting whether these studies are indifferent or respectful or whether there is under reporting or over reporting would result in a false estimation. The studies included in this review do not follow the same methodology. Various scales, tools, and methods of data collection were employed. This has an effect on the prevalence of the components of respectful maternity care. The data should be reported with caution, because of the high heterogeneity. Nevertheless, this study still highlights an important issue that will aid in developing women centered targeted interventions, appropriate tools to measure RMC based on determinants and finally help in policy and program implementation.

The analysis identifies the need for robust prevalence estimates. It is essential to identify whether studies should be conducted at the health facility or community. Firstly, data collected at community level gives information of the various hospitals as it is would be difficult to include mothers from each and every health facility. Secondly, it has been observed from the studies that mothers were reluctant to answer at the hospital and there is underreporting and discordance between data reported and observed.[8] Thirdly, data on observation has to be collected at the health facility, but presence of the researcher in a hospital might influence the results. However, data obtained at the facilities gives first-hand information of ill-treatment and it is easier to obtain data on ill-treatment based on geographical distribution of health facilities. At community level, cultural practices like delivery at the maternal residence or choice-based selection of health facility for delivery might confound the community data in terms of geographical distribution of ill-treatment and it would be difficult to trace women delivering at a specific health facility at a specific time in the community. Data collected via interviews at health facilities or communities may be influenced by recall bias and social desirability bias. Inclusion of women with complications or those who have undergone medical termination of pregnancies is also essential or there would be underestimation. Consistent methodologies and standardized definitions will help to achieve comparability across settings.[27] Furthermore, to improve RMC, it is essential to understand the perception of the various stakeholders involved and the health system issues to develop measures for improvement. Ill-treatment could also be explored among women at all stages, including the antenatal, natal, and postnatal period to develop an integrated RMC approach.

Conclusion

The systematic review and meta-analysis identified that the prevalence of disrespectful maternity care is high in the country. The highest reported forms of ill-treatment were non consent, verbal abuse, threats, physical abuse, and discrimination. Sociocultural and environmental factors were identified as determinants of ill-treatment. The analysis also identified the need to achieve comparability across settings by developing tools, consistent methodologies, and standardized definitions. In conclusion, there is a nation-wide need to focus on the quality of care delivered at the health facilities. This can be achieved by development of targeted interventions and implementation of policies and programs that will eliminate disrespect and ensure respectful maternity care at all settings.

Financial support and fellowship

Funding support from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India for INSPIRE Fellowship to Dr. Humaira Ansari is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.The Lancet Maternal Health Series. [Internet] 2016. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 31]. Available from: www.maternalhealthseries.org .

- 2.The White Ribbon Alliance for Safe motherhood. Respectful maternity care: The universal rights of childbearing women White Ribbon Alliance [Internet] 2011. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 31]. Available from: https://wwwwhiteribbonallianceorg/wp-content/up loads/2017/11/Final_RMC_Char terpdf .

- 3.La Moher D, Tetzlaff J, Altman D The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Evidence Based Management. Critical Checklist for Cross-Sectional Study [Internet] 2014. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 31]. Available from: https://wwwcebmaorg/resources-and-to ols/what-is-critical-appraisal/

- 5.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [Internet] 2018. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 31]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/upl oads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf .

- 6.Sharma G, Penn-Kekana L, Halder KF. An investigation into mistreatment of women during labour and childbirth in maternity care facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India: A mixed methods study. Reprod Heal. 2019;16:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0668-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharya S, Sundari Ravindra T. Silent voices: Institutional disrespect and abuse during delivery among women of Varanasi district, northern India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dey A, Shakya HB, Chandurkar D, Kumar S, Das AK, Anthony J, et al. Discordance in self-report and observation data on mistreatment of women by providers during childbirth in Uttar Pradesh, India. Reprod Heal. 2017;14:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0409-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raj A, Dey A, Boyce S, Seth A, Bora S, Chandurkar D, et al. Associations between mistreatment by a provider during childbirth and maternal health complications in Uttar Pradesh, India. Matern Child Heal J. 2017;21:1821–33. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nawab T, Erum U, Amir A, Khalique N, Ansari MA, Chauhan A. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth and its sociodemographic determinants-A barrier to healthcare utilization in rural population. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8:239–45. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_247_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh A, Chhugani PM, James MM. Direct observation on Respectful maternity care in India: A cross sectional study on health professionals of three different health facilities in New Delhi. Indian J Sci Res. 2018;7:821–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudhinaraset M, Treleaven E, Melo J, Singh K, Diamond-Smith N. Women's status and experiences of mistreatment during childbirth in Uttar Pradesh: A mixed methods study using cultural health capital theory. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1124-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen HE, Lynam PF, Carr C, Reis V, Ricca J, Bazant ES, et al. Direct observation of respectful maternity care in five countries: A cross-sectional study of health facilities in East and Southern Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sando D, Ratcliffe H, Mcdonald K, Spiegelman D, Lyatuu G, Mwanyika-Sando M, et al. The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kassa ZY, Husen S. Disrespectful and abusive behavior during childbirth and maternity care in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesenburg MA, Victora CG, Serruya SJ, León RP De, Damaso AH, Domingues MR, et al. Disrespect and abuse of women during the process of childbirth in the 2015 Pelotas birth cohort. Reprod Heal. 2018;15:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0495-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altahir A, Alaal AA, Mohammed A, Eltayeb D. Proportion of disrespectful and abusive care during childbirth among women in Khartoum State-2016. Am J Public Heal Res. 2018;6:237–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azhar Z, Oyebode O, Masud H. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth in district Gujrat, Pakistan: A quest for respectful maternity care. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hameed W, Avan BI. Women's experiences of mistreatment during childbirth: A comparative view of home- and facility-based births in Pakistan. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montesinos-Segura R, Urrunaga-Pastor D, Mendoza-Chuctaya G, Taype-Rondan A, Helguero-Santin LM, Martinez-Ninanqui FW, et al. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth in fourteen hospitals in nine cities of Peru. Int J Gynaecol Obs. 2018;140:184–90. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza J, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12:1–32. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shakibazadeh E, Namadian M, Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Rashidian A, Nogueira Pileggi V, et al. Respectful care during childbirth in health facilities globally: A qualitative evidence synthesis. BJOG. 2018;125:932–42. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cham M, Sundby J, Vangen S. Availability and quality of emergency obstetric care in Gambia's main referral hospital: Women-users' testimonies. Reprod Heal. 2009;6:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chodzaza E, Bultemeier K. Service providers' perception of the quality of emergency obsteric care provided and factors indentified which affect the provision of quality care. Malawi Med J. 2010;22:104–11. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v22i4.63946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jha P, Christensson K, Svanberg AS, Larsson M, Sharma B, Johansson E. Cashless childbirth, but at a cost: A grounded theory study on quality of intrapartum care in public health facilities in India. Midwifery. 2016;39:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lahariya C. 'Ayushman Bharat' program and universal health coverage in india. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55:495–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sudhinaraset M, Beyeler N, Barge S, Diamond-Smith N. Decision-making for delivery location and quality of care among slum-dwellers: A qualitative study in Uttar Pradesh, India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0942-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]