Abstract

Introduction:

The choice of restorative materials has for a long time been determined by the tooth position. Thus, premolar restoration depended on the practitioner's clinical assessment and practical experience in regard to the material to be handled.

Aim:

The objective of this study was to assess, in the students' practice, the change in the choice of materials used for premolars restoration.

Materials and Methods:

This was a retrospective study based on the available care records in the department of conservative dentistry and endodontics of a dental school. Variables analyzed included the year of restoration, the type of material, the premolar position in the arch, and the coronal restoration site (occlusal, proximal, and cervical). Data collected were processed with the SPSS software version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA; 2013). The statistical significance threshold was set at 5% for Pearson's Chi-square test.

Results:

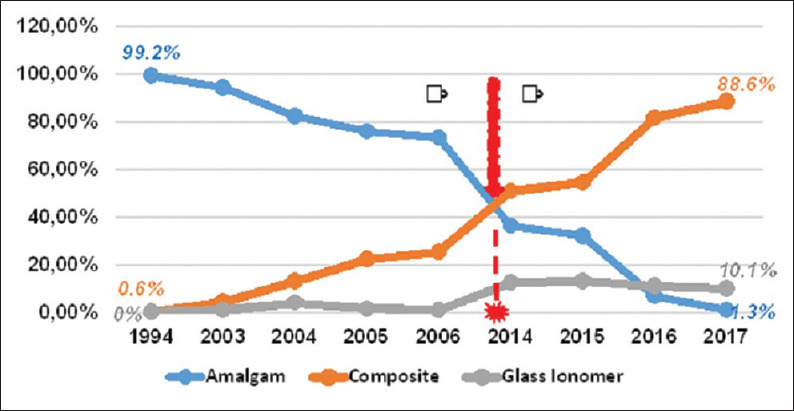

Between 1994 and 2017, 1738 restored premolars were identified. Over the years, amalgam restorations declined from 99.2% in 1994 to 1.3% in 2017, contrary to composite whose frequency increased from 0.6% to 88.6%. Maxillary premolars were exclusively restored with composite in 2017 when amalgam was still, somewhat, used for mandibular premolars.

Conclusion:

The reversal in the choice of materials in favor of composites reflects the global trend. This seems to be related to the current awareness of the prohibition, among others, of medical devices containing mercury.

Keywords: Amalgam, composite, glass ionomer cement, premolar restoration

INTRODUCTION

Direct technique coronal filling materials are conventionally classified according to mechanical (amalgam), esthetic (composite), and biological (glass ionomer cement [GIC]) considerations.[1,2] The position of the tooth to be restored has long been a key criterion. In this context, the amalgam's superior mechanical properties made it the exclusively ideal material for the restoration of teeth that are subjected to major masticatory stress. For obvious esthetic reasons, composite is used for anterior teeth restoration.

The position of premolars in the arches implies that they would be dependent on anterior and posterior teeth's functionality. Indeed, they are involved in the occlusion stability, the mastication, and the smile esthetic.[3,4] However, there's very poor literature in the choice of material adequate for these teeth restoration by direct technique while they are the second group of teeth affected by the carious disease.[5] According to the literature, these teeth are more susceptible to non-carious cervical lesions.[6] Intermediate tooth status implies that their restoration depends on the practitioner's clinical assessment and his experience with the material to be handled. In addition, dental undergraduate curricula scrutiny reveals changes in favor of the teaching of posterior tooth adhesive restorations.[7] In 2014, the European Academy of Operative Dentistry validated the composite resin posterior tooth restoration in almost any clinical situation by developing guidelines regarding their technical aspect implementation.[8] The time required for the clinical implementation of new therapeutic approaches is unknown in practice. Moreover, in practice, the therapeutic choice of metallic or adhesive materials is poorly documented. The objective of this study was to assess, in the students' practice, the change in the choice of materials used for premolar restoration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study based on the available care records in the conservative dentistry and endodontic department of a dental school. This department is dedicated, in collaboration with other specialties, to providing clinical training to intern students. During clinical placements, all treatments validated by the teachers are recorded in registers to monitor the students' clinical quotas. Were included in this study, all recorded amalgam, composite and glass ionomer cement restorations performed on premolars prior to January 1, 2018. Analyses were performed year after year to assess the frequency of the use for similar types of material. For a given year, comparisons were made between different types of materials according to the following four variables: the restoration year, the tooth topography (1st or 2nd premolar, maxillary or mandibular), the restoration site (occlusal, proximal, and cervical), and the tooth vitality (a vital tooth or not). Data collected were processed using SPSS software version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, 2013). The statistical significance threshold was set at 5% for the Pearson's Chi-square test.

RESULTS

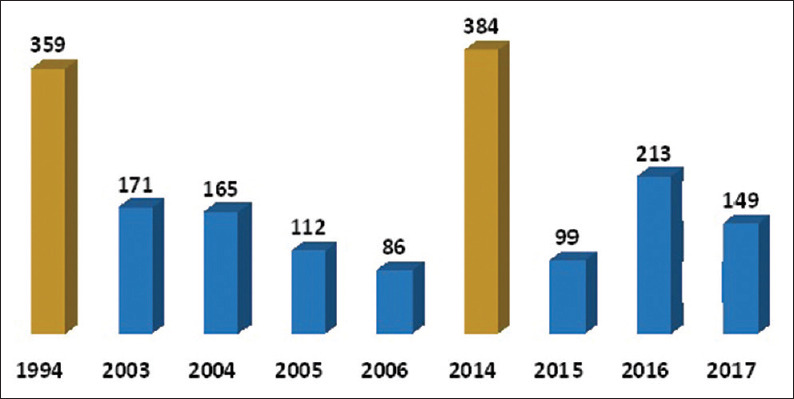

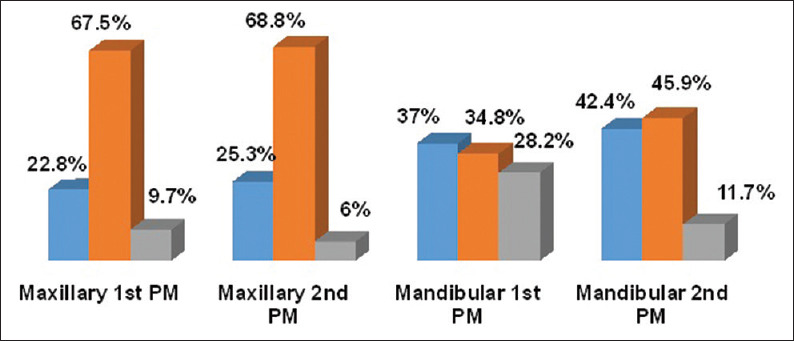

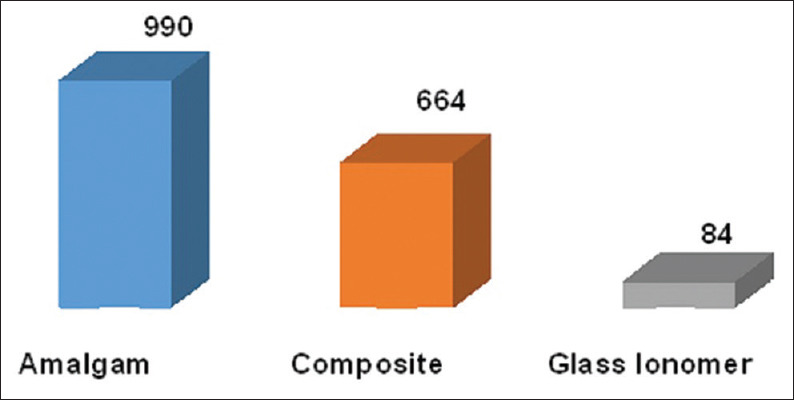

The available records were from 1994, 2003 to 2006 and 2014 to 2017. The inventory provided 1738 coronal restorations, whose distributions are provided in Figure 1. Most of the restorations done on teeth were for maxillary premolars and proximal surfaces [Figure 2]. The distribution of materials over the entire period of 1994–2017 is shown in [Figures 3 and 4]. As of 2014, vital pulp teeth and nonvital teeth are essentially restored with adhesive materials [Figure 5].

Figure 1.

Distribution of premolar restorations from 1994 to 2017. The largest number of restorations was recorded in 1994 and 2014. The differences were due to the variation in the number of students per academic year.

Number of restorations

Number of restorations

Figure 2.

Distribution of restorations from 1994 to 2017 according to premolars and dental sites: Most direct technique coronal restorations were maxillary premolars and proximal (P = 0.000, significant differences observed).  Occlusal

Occlusal  Proximal

Proximal  Cervical

Cervical

Figure 3.

Number of materials on all premolar restorations between 1994 and 2017: There were more amalgam coronal restorations than any other coronal restorations.  Amalgam

Amalgam  Composite

Composite  Glass Ionomer

Glass Ionomer

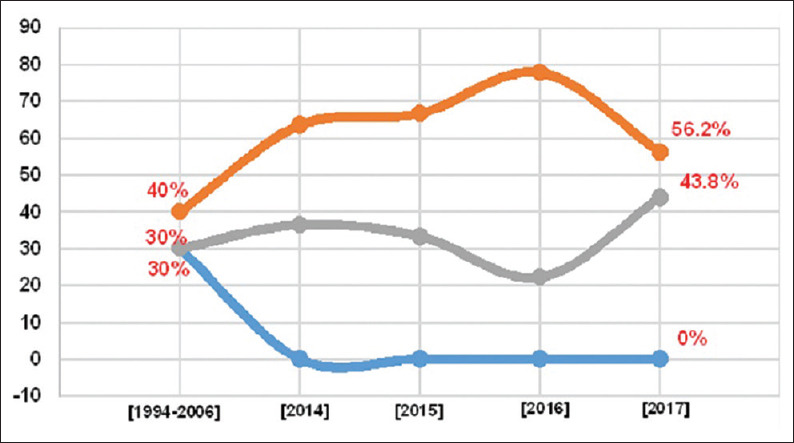

Figure 4.

Patterns in the material choice by year: The 2014 academic year was the cutoff point for a radical change in the choice of restorative materials in favor of composite and GIC. (P = 0.000, significant observed differences).  Amalgam

Amalgam  Composite

Composite  Glass Ionomer

Glass Ionomer

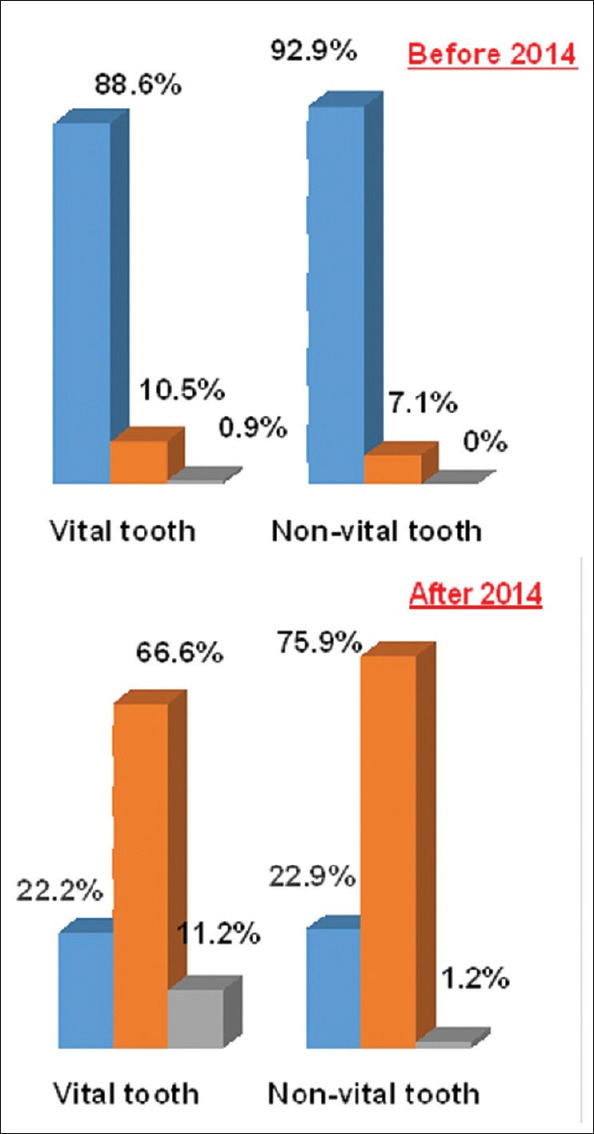

Figure 5.

As of 2014, vital pulp teeth and non-vital teeth are essentially restored with adhesive materials (P = 0.5. Observed differences are not significant).  Amalgam

Amalgam  Composite

Composite  Glass Ionomer

Glass Ionomer

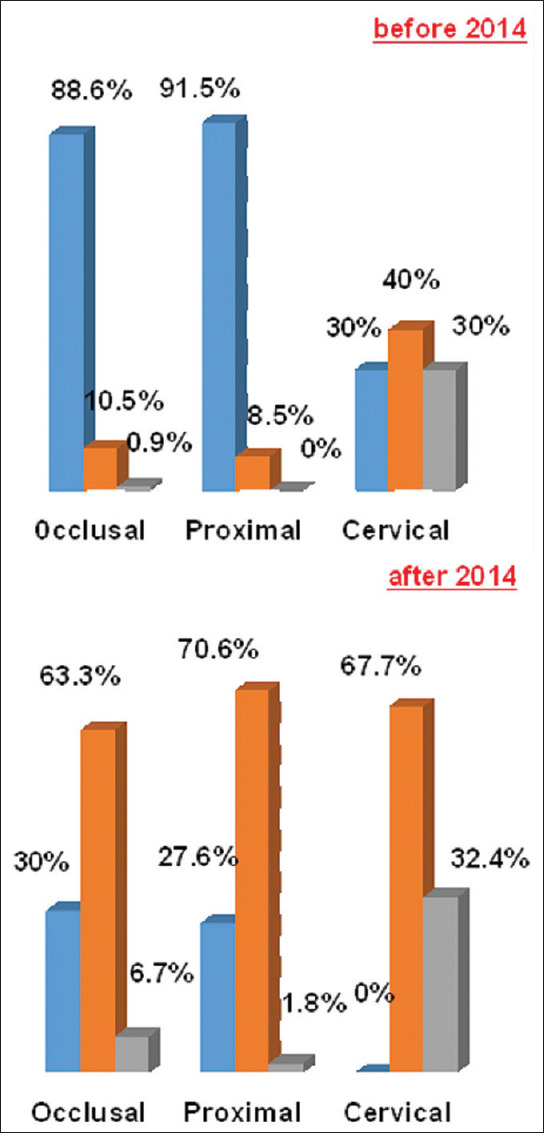

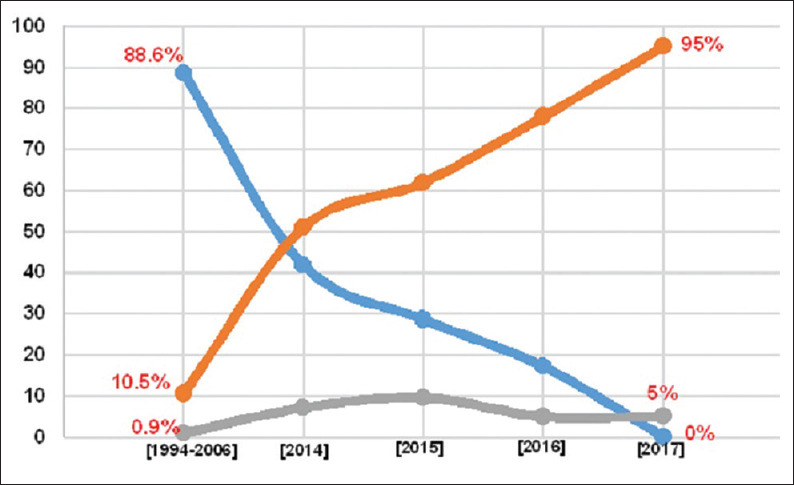

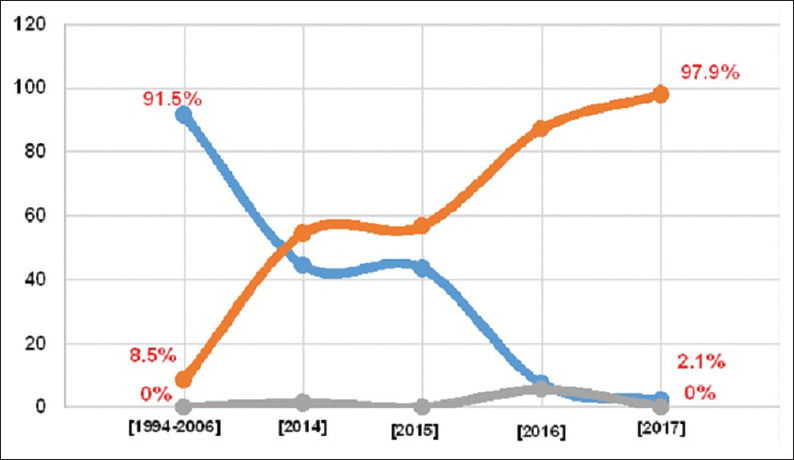

Reverse increase in adhesive materials after 2014 is similar for restored sites [Figure 6]. The pace of material change after 2014 indicates that most of the devitalized teeth (97%) were restored with composite in 2017. In that same year, occlusal restoration was performed with composite (95%), GIC (5%) [Figure 7], proximal surface restoration with amalgam (2.1%) and composite (97.9%) [Figure 8], and cervical area restoration with composite (18%) and GIC (18%) [Figure 9].

Figure 6.

Distribution of materials according to the restored site: Before 2014, amalgam was used in cervical area restorations; after 2014, this site is exclusively restored with composite and glass ionomer cement; the latter is also found in occlusal and proximal surface restorations. (P = 0.000, significant observed differences).  Amalgam

Amalgam  Composite

Composite  Glass Ionomer

Glass Ionomer

Figure 7.

Patterns of material used for occlusal surface restoration: No amalgam restoration was performed in 2017. (P = 0.000, significant observed differences).  Amalgam

Amalgam  Composite

Composite  Glass Ionomer

Glass Ionomer

Figure 8.

Patterns of materials used for proximal face restoration during the last 4-year period (2014–2017): Glass ionomer cement proximal face restorations were found in 2015 and 2016. (P = 0.000, significant observed differences).  Amalgam

Amalgam  Composite

Composite  Glass Ionomer

Glass Ionomer

Figure 9.

Patterns of materials used for cervical area restoration: Since 2014, no cervical area restoration has been done with amalgam. (P = 0.000, significant observed differences).  Amalgam

Amalgam  Composite

Composite  Glass ionomer

Glass ionomer

DISCUSSION

The patterns in the choice of materials by year show decreased use of amalgam from 99.2% to 1.3% as opposed to the composite's which increased from 0.6% to 88.6%. Recent years have witnessed a progressive disappearance of the metallic material, in line with the worldwide trend as shown by works in dental faculties.[7] However, according to these authors, an adjustment period is required between the training of these new therapeutic approaches and their clinical practice.

The retrospection begins in 1994, in the 1990–2000 decade, with the advent of microhybrid composites (1990), GIC modified by resin addition (1991), flowable composites (1996), packable composites (1997), and nanohybrid composites (1998).[1] This decade is considered that of the composite resins' 2nd revolution.[9] These never-ending developments have constantly impacted dentists' practice with regard to the wide choice of materials now available to them. Findings over the years show that from 2014, most premolar restorations are performed with adhesive materials.

The amount of coronal restorations (1738) reflects the frequency of substance loss in premolars. This study also shows that mandibular premolars are less affected by substance loss than their maxillary counterparts. This might be due to the salivary flow for the carious factor. As it was, one might think that mandibular premolars are bathed in saliva because they are near the floor of the mouth and would consistently benefit more from salivary buffering capacity than maxillary teeth. In addition, more easily accessible for dental brushing, the maxillary premolars could face mechanical friction due to poor brushing techniques, with eventually a gingival recession often with a non carious cervical lesion.[6]

Over the years, the choice of material according to the tooth vitality and the site to be restored shows increased use of adhesive materials to the detriment of amalgam. In biomechanics, vital tooth restoration with adhesive materials has the advantage of tissue-economy (preservation of unsupported peripheral enamel and preservation of demineralized dentin) and adhesion mechanism (sealing ensured by material bonding prevents percolation and recurrent caries).[2] During restoration, on one hand, preserving structures such as marginal ridges maintains the intrinsic strength of the tooth, and on the other hand, the bond strength to the dentin and enamel helps strengthen the restored tooth.[2] In this study, the financial criterion is a factor for nonvital tooth amalgam restoration. Few patients are covered by health insurance in Côte d'Ivoire.[10] In addition, patient's contribution can also influence the choice of material. GIC occlusal restorations seem to be affected by this financial criterion. Because of their insufficient mechanical strength compared to composites, GIC are recommended for small cavities and in time-delay restorations in patients with poor oral hygiene. However, 5% of restorations in 2017 were occlusal restorations. This could be temporary restorations on vital pulp teeth. For nonvital and severely damaged teeth, GIC can be the indicated material for an inexpensive core for a prosthetic crown.

Studies on the assessment of conservative therapies focus on students because their restorations' success rate is close to that of practitioners.[11] There is a divergence of opinion for the restoration of extensive cavities by direct technique when the patient's financial issue arises.[12] It would appear that supervisors with <10 years of experience train students about composite use in hypothetical situations compared to more experienced ones.[13] A recent survey conducted in 2014 reflected this trend by showing that dentists with more than15 years of professional experience still prefer amalgam to composite, unlike younger practitioners.[14] Results of this study suggest that future practitioners will be more oriented toward the use of composite. Thus, for premolar restoration, the exclusive use of adhesive materials seems to be for some years to come.

Records used in this study did not provide information on the choice of material associated with the restored proximal side (mesial, distal, buccal, and lingual) and neither the size to be restored (one-third, one-half, or more of the crown). It is the same for the cause of substance loss (carious or noncarious lesions). Results of this study are exploratory for continuing investigation of those aspects.

CONCLUSION

This study shows a reversal between amalgam and composite for premolar restoration. The interest of this survey was to show that adhesive restorations on posterior teeth are approved for premolar rehabilitation. Apart from controversies related to the use of amalgam, today, premolars may be completely restored with adhesive material. For this, oral hygiene, individual carious risk, and the patient's financial possibilities should be evaluated.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hickel R, Dasch W, Janda R, Tyas M, Anusavice K. New direct restorative materials. FDI commission project. Int Dent J. 1998;48:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1998.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Souza Costa CA, Hebling J, Scheffel DL, Soares DG, Basso FG, Ribeiro AP. Methods to evaluate and strategies to improve the biocompatibility of dental materials and operative techniques. Dent Mater. 2014;30:769–84. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDevitt WE, Warreth AA. Occlusal contacts in maximum intercuspation in normal dentitions. J Oral Rehabil. 1997;24:725–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.1997.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu H, Han X, Wang Y, Shu R, Jing Y, Tian Y, et al. Effect of buccolingual inclinations of maxillary canines and premolars on perceived smile attractiveness. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015;147:182–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denloye OO, Ajayi DM, Popoola BO. Dental caries prevalence and bilateral occurrence in premolars and molars of adolescent school children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Odontostomatol Trop. 2015;38:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soares PV, Souza LV, Veríssimo C, Zeola LF, Pereira AG, Santos-Filho PC, et al. Effect of root morphology on biomechanical behaviour of premolars associated with abfraction lesions and different loading types. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41:108–14. doi: 10.1111/joor.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson NH, Lynch CD. The teaching of posterior resin composites: Planning for the future based on 25 years of research. J Dent. 2014;42:503–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch CD, Opdam NJ, Hickel R, Brunton PA, Gurgan S, Kakaboura A, et al. Guidance on posterior resin composites: Academy of operative dentistry-European section. J Dent. 2014;42:377–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayne SC. Beginnings of the dental composite revolution. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:880–4. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sangare AD, Samba M, Bourgeois D. Illness- related behavior and sociodemographic determinants of oral health care use in Dabou. Côte d'Ivoire Community Dent Heath. 2012;29:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naghipur S, Pesun I, Nowakiwski A, Kim A. Twelve-year survival of 2-surface composite rein and amalgam premolar restorations placed by dental students. J Prosthet Dent. 2016;116:336–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin R, Eliyas S, Burke FJ, Taylor P, Toner J, Briggs P. British Society of Prosthodontics Debate on the implications of the minamata convention on mercury to dental amalgam–should our patients be worried? Dent Update. 2016;43:8. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-Gal G, Weiss EI. Trends in material choice for posterior restoration in an Israeli dental school: Composite resin versus amalgam. J Dent Educ. 2011;75:1590–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalaf ME, Alomari QD, Omar R. Factors relating to usage patterns of amalgam and resin composite for posterior restorations-a prospective analysis. J Dent. 2014;42:785–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]