Abstract

Background

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common and serious microvascular complication of diabetes. Taohong Siwu decoction (THSWD), a famous traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) prescription, has been proved to have a good clinical effect on DR, whereas its molecular mechanism remains unclear. Our study aimed to uncover the core targets and signaling pathways of THSWD against DR.

Methods

First, the active ingredients of THSWD were searched from Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) Database. Second, the targets of active ingredients were identified from ChemMapper and PharmMapper databases. Third, DR associated targets were searched from DisGeNET, DrugBank and Therapeutic Target Database (TTD). Subsequently, the common targets of active ingredients and DR were found and analyzed in STRING database. DAVID database and ClueGo plug-in software were used to carry out the gene ontology (GO) and KEGG enrichment analysis. The core signaling pathway network of “herb-ingredient-target” was constructed by the Cytoscape software. Finally, the key genes of THSWD against DR were validated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR).

Results

A total of 2340 targets of 61 active ingredients in THSWD were obtained. Simultaneously, a total of 263 DR-associated targets were also obtained. Then, 67 common targets were found by overlapping them, and 23 core targets were identified from protein-protein interaction (PPI) network. Response to hypoxia was found as the top GO term of biological process, and HIF-1 signaling pathway was found as the top KEGG pathway. Among the key genes in HIF-1 pathway, the mRNA expression levels of VEGFA, SERPINE1 and NOS2 were significantly down-regulated by THSWD (P < 0.05), and NOS3 and HMOX1 were significantly up-regulated (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

THSWD had a protective effect on DR via regulating HIF-1 signaling pathway and other important pathways. This study might provide a theoretical basis for the application of THSWD and the development of new drugs for the treatment of DR.

Keywords: Taohong Siwu decoction, Diabetic retinopathy, HIF-1 signaling pathway, Network pharmacology, Angiogenesis

Background

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common and serious microvascular complication of diabetes, which is an important cause of permanent vision loss in middle-aged and elderly people. One-third of people with diabetes have DR. [1] Previous study reported that 2.6 million people were visually impaired (moderate to severe vision impairment or even blindness) resulting from DR in 2015 and it was estimated to rise to 3.2 million in 2020 [2]. Furthermore, DR not only reduces the quality of life, but also increases the risk of other diabetes complications and even mortality, which brings severe social and family burdens [3]. Currently, the therapeutic approaches of DR mainly include surgery, laser photocoagulation, hormone, and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drug. However, the current treatment could bring some adverse reactions, such as high intraocular pressure, angiogenesis, retinal hemorrhage, and so on [4, 5]. Therefore, it is urgent to discover promising therapeutic targets and develop new therapeutic strategies for DR patients.

The pathogenesis of DR is complicated because multiple factors induce the disease. Currently, it is believed that DR is closely associated with glucose metabolism and microvascular status. In specific, glucose metabolic disorder will lead to microvascular alternation and microcirculation dysfunction, subsequently retina ischemia and hypoxia, and finally occurrence of retinopathy [6, 7]. Previous studies reported that hypoxia played an essential role in DR progression via promoting neovascularization and vascular dystrophies [8–10]. Some researchers found that the retinas of diabetic patients could quickly response to hyperglycemia and hypoxia, resulting in the imbalance between pro-angiogenesis and anti-angiogenesis [11]. Thus, the treatments which focus on hypoxia-related signaling pathways and targets may be the novel and promising therapeutic strategies for DR.

Taohong Siwu decoction (THSWD) is a famous traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) prescription, and was first recorded in a well-known medical book Yizong Jinjian compiled by Wu Qian in Qing Dynasty [12]. It consists of six herbs, including Persicae Semen (Taoren, TR), Carthami Flos (Honghua, HH), Rehmanniae Radix Praeparata (Shudihuang, SHH), Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui, DG), Paeoniae Radix Alba (Baishao, BS), and Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong, CX) (Table 1). Several studies have reported that THSWD had a good clinical effect on the treatment of DR. [13] However, the pharmacological mechanism of THSWD on DR therapy remains unclear, which restricts the wide use of THSWD.

Table 1.

The ingredients of THSWD

| Chinese name | Pharmaceutical name | Botanical plant name | English name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tao Ren | Persicae Semen | Prums persica (L.) Batsch | Peach Seed |

| Hong Hua | Carthami Flos | Carthamus tinctorius L. | Safflower |

| Shu Di Huang | Rehmanniae Radix Praepata | Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch. | Chinese Fox-Glove Root |

| Dang Gui | Angelicae Sinensis Radix | Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels | Chinese Angelica |

| Bai Shao | Paeoniae Radix Alba | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. | White Peony Root |

| Chuan Xiong | Chuanxiong Rhizoma | Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort. | Szechwan Lovage Rhizome |

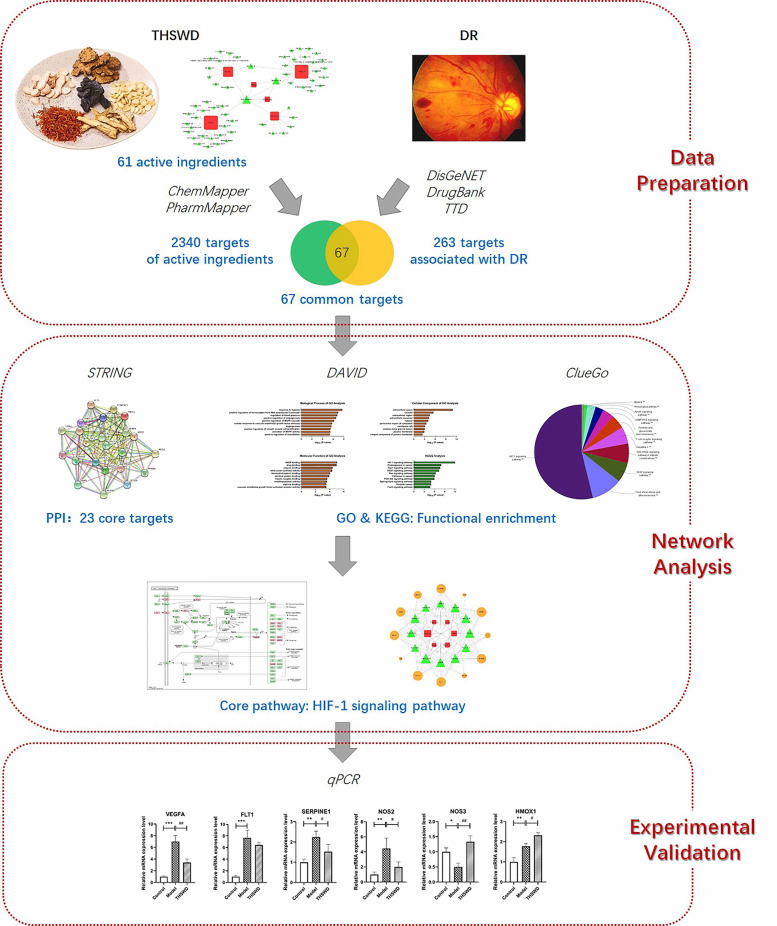

In this study, network pharmacology and experimental validation were conducted to explore the mechanism of THSWD on DR therapy (Fig. 1). Firstly, the targets of THSWD against DR were searched and screened. Subsequently, network analysis was applied to explore the core signaling pathways and targets. Finally, in vitro experiments were performed to validate the molecular mechanism of THSWD on the treatment of DR, and hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1)-related pathways and targets were found involved in THSWD against DR. Our study maybe explains the therapeutic mechanism of THSWD at the molecular level and provides the theoretical basis for the wide use of THSWD on the treatment of DR.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart for exploring the molecular mechanisms of THSWD against DR

Methods

Data preparation

Searching for active ingredients of THSWD

Ingredients of each herb in THSWD were searched from Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) Database (http://lsp.nwu.edu.cn/tcmsp.php), a unique pharmacology platform that collects a great deal of information about herbal ingredients, targets and disease [14]. The active ingredients were filtered by meeting the criteria of oral bioavailability (OB ≥ 30%) and drug-likeness (DL ≥ 0.18) as previous study [15]. An interaction network of herb-ingredient was constructed and visualized by the Cytoscape software (version 3.2.1, Boston, MA, USA).

Identification of targets of active ingredients

ChemMapper (http://lilab.ecust.edu.cn/chemmapper/) and PharmMapper (http://lilab.ecust.edu.cn/pharmmapper/index.php) databases were used to predict the targets of each active ingredient. ChemMapper database is a versatile web server for exploring pharmacology and chemical structure association based on molecular 3D similarity method [16]. The screening criteria were 3D structure similarity above 0.85 and prediction score above 0. PharmMapper database is another web server for identifying potential drug targets according to the target pharmacophore approach [17]. The druggable pharmacophore models were set and the top 100 reserved matched targets were selected with default parameters.

Searching for DR-associated targets

DR-associated targets were searched with keywords “diabetic retinopathy”, “proliferative diabetic retinopathy”, and “nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy” in DisGeNET database (http://www.disgenet.org/web/DisGeNET/menu/home), DrugBank database (https://www.drugbank.ca/), and Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (https://db.idrblab.org/ttd/) which contain collections of genes and variants associated to human diseases [18–20].

Network analysis

Construction and analysis of protein-protein interaction (PPI)

The PPI of candidate targets of THSWD against DR were collected from STRING database (https://string-db.org/), which integrates the quality-controlled protein-protein association networks of a large number of organisms [21]. The criteria for PPI selection were those with the confidence score above 0.9 and the degree score above the average value.

Functional enrichment analysis

The candidate targets of THSWD against DR were imported into DAVID database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) for the Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis. DAVID database provides systematic and comprehensive bioinformatics annotations for large-scale gene or protein lists based on both biological data and analysis tools [22].

The candidate targets of THSWD against DR were further analyzed with a Cytoscape plug-in software, ClueGo. GlueGo was used to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks [23]. P < 0.05 was regarded as the significant cutoff in this study.

Pathway network construction

Based on the data of herb-ingredient-target-pathway obtained by previous steps, the core signaling pathway network of THSWD against DR was constructed by the Cytoscape software. The critical active ingredients and candidate targets were filtered based on the criterion of degree score above the average value.

Experimental validation

Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis

A liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry system, AB Sciex Triple TOF® 4600, was used for the separation and identification of THSWD. The separation was performed on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm, Lot: 0200372571). A linear gradient elution of A (0.1% formic acid-H2O) and B (acetonitrile) was used with the gradient procedure as list in Table 2. DAD was on and the target wavelength was simultaneously set at 254 nm. MS parameters were set as list in Table 3. Approximately 1 ml of the sample was dissolved in 10 mL water. The solution was centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatants of sample solutions were filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter prior to LC/MS analysis.

Table 2.

Mobile phase gradient

| Time (min) | Flow Rate (ml/min) | %B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.3 | 0 |

| 8 | 0.3 | 0 |

| 10 | 0.3 | 3 |

| 28 | 0.3 | 10 |

| 35 | 0.3 | 15 |

| 43 | 0.3 | 20 |

| 48 | 0.3 | 25 |

| 55 | 0.3 | 40 |

| 62 | 0.3 | 60 |

| 68 | 0.3 | 95 |

| 73 | 0.3 | 95 |

| 73.1 | 0.3 | 0 |

| 76 | 0.3 | 0 |

Table 3.

Mass parameters

| MS parameters | parameter | MS/MS parameter | parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOF mass range | 100 ~ 1500 | MS/MS mass range | 100 ~ 1500 |

| Ion Source Gas 1 | 50 | Declustering Potential | 100 |

| Ion Source Gas 2 | 50 | Collision Energy | ±40 |

| Curtain Gas | 35 | Collision Energy Spread | 20 |

| Ion Spray Voltage Floating (kV) | − 4500/5000 | Ion Release Delay | 30 |

| Ion Source Temperature (°C) | 500 | Ion Release Width | 15 |

| Declustering Potential | 100 | ||

| Collision Energy | 10 |

Cell culture and treatment

Human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (hRMECs) were purchased from Shanghai Bioleaf Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and cultured in endothelial cell medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum, supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% endothelial cell growth supplement (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. hRMECs were treated with 30 mM glucose alone to simulate DR or in combination with 100 μg/ml THSWD for 24 h. Cells without any treatments were used as control.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The quality of RNA was measured by Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), and equal amounts of RNA were reverse-transcribed into cDNA using First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Gene primer pairs used in this study are list in Table 4. qRT-PCR was carried out using ABI 7500 System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) under the following parameters: 95 °C for 30s, 95 °C for 5 s (40 cycles), 60 °C for 30s, and 72 °C for 15 s. Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using GAPDH as the internal control and the 2-△△CT method. Each sample was run three times.

Table 4.

Gene primer pairs used for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| VEGFA | 5′-GAGCCTTGCCTTGCTGCTCTAC-3′ | 5′-CACCAGGGTCTCGATTGGATG-3′ |

| FLT1 | 5′-GCATATGGTATCCCTCAACCTACAA-3′ | 5′-CATCCAGGATAAAGGACTCTTCATTAT-3′ |

| SERPINE1 | 5′-CAGACCAAGAGCCTCTCCAC-3′ | 5′-GGTTCCATCACTTGGCCCAT-3′ |

| NOS2 | 5′-CGGTGCTGTATTTCCTTACGAGGCGAAGAAGG-3′ | 5′-GGTGCTGCTTGTTAGGAGGTCAAGTAAAGGGC-3′ |

| NOS3 | 5′-GACCCTCACCGCTACAACAT-3′ | 5′-CCGGGTATCCAGGTCCAT-3′ |

| HMOX1 | 5′-CTGGGCTGGGGACAGTGG-3′ | 5′-GAAAAGAGAGCCAGGCAAGAT-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-CGCTCTCTGCTCCTCCTGTT-3’ | 5′-CCATGGTGTCTGAGCGATGT-3’ |

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA analysis, followed by Dunnett post hoc test, was used to determine significant differences between different groups using the SPSS software (version 21.0, Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Candidate targets of THSWD against DR

Active ingredients of THSWD

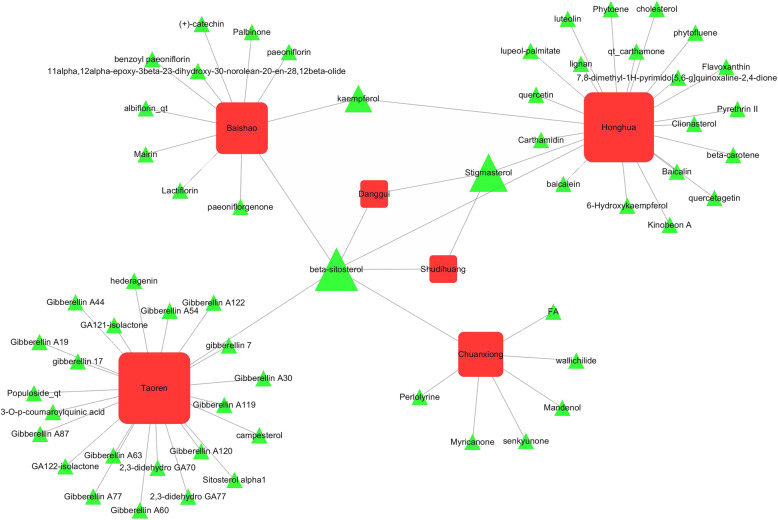

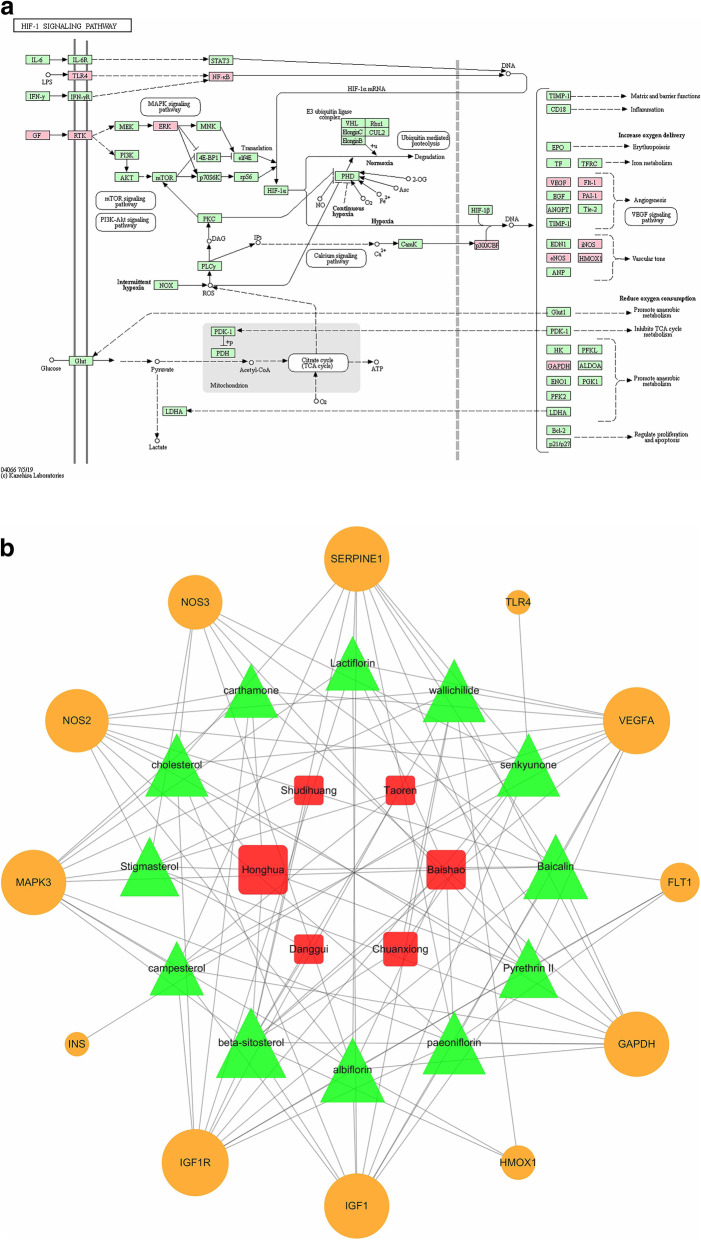

A total of 722 ingredients in THSWD were found from TCMSP database. According to the screening criteria of OB ≥ 30% and DL ≥ 0.18, we filtered out 23 active ingredients in TR, 22 active ingredients in HH, 2 active ingredients in SDH, 2 active ingredients in DG, 13 active ingredients in BS, and 7 active ingredients in CX. After overlapped ingredients were subtracted, a total of 61 active ingredients in THSWD were obtained. Detailed information about active ingredients of THSWD was provided in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Sixty one active ingredients obtained in THSWD. The red square represents herbs in THSWD, and the green triangle represents active ingredients of those herbs

Targets of active ingredients in THSWD

We found 1567 targets of TR, 1656 targets of HH, 468 targets of SDH, 741 targets of DG, 1567 targets of BS, and 1307 targets of CX. After overlapped targets were subtracted, a total of 2340 targets of THSWD were obtained, including 1186 targets from ChemMapper database and 1182 from PharmMapper database. Detailed information about targets of active ingredients in THSWD was provided in Supplementary Table 2.

DR-associated targets

After overlapped targets were subtracted, a total of 263 DR-associated targets were obtained, including 258 DR-associated targets from DisGeNET Database, 3 ones from DrugBank database, and 7 ones from TTD database. Detailed information about DR-associated targets was provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Targets of THSWD against DR

The targets of active ingredients in THSWD were overlapped with DR-associated targets. A total of 67 candidate targets of THSWD against DR were identified. Detailed information about targets of THSWD against DR was provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Targets of THSWD against DR

| UniProt ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|

| P20248 | CCNA2 | cyclin A2 |

| P12821 | ACE | angiotensin I converting enzyme |

| P09488 | GSTM1 | glutathione S-transferase mu 1 |

| P08473 | MME | membrane metalloendopeptidase |

| P09038 | FGF2 | fibroblast growth factor 2 |

| Q07869 | PPARA | peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha |

| P15692 | VEGFA | vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| P04406 | GAPDH | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| Q04760 | GLO1 | glyoxalase I |

| P37231 | PPARG | peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma |

| P35354 | PTGS2 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 |

| P01112 | HRAS | HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase |

| P29475 | NOS1 | nitric oxide synthase 1 |

| P08069 | IGF1R | insulin like growth factor 1 receptor |

| P30556 | AGTR1 | angiotensin II receptor type 1 |

| P05019 | IGF1 | insulin like growth factor 1 |

| P27361 | MAPK3 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 |

| P01375 | TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| P14780 | MMP9 | matrix metallopeptidase 9 |

| P05091 | ALDH2 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 family (mitochondrial) |

| P05121 | SERPINE1 | serpin family E member 1 |

| Q00796 | SORD | sorbitol dehydrogenase |

| P22392 | NME2 | NME/NM23 nucleoside diphosphate kinase 2 |

| P00403 | MT-CO2 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit II |

| Q16698 | DECR1 | 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase 1, mitochondrial |

| P14550 | AKR1A1 | aldo-keto reductase family 1 member A1 |

| P09601 | HMOX1 | heme oxygenase 1 |

| P15121 | AKR1B1 | aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B |

| P29474 | NOS3 | nitric oxide synthase 3 |

| Q16539 | MAPK14 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 |

| O60218 | AKR1B10 | aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10 |

| P18031 | PTPN1 | protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 1 |

| P55017 | SLC12A3 | solute carrier family 12 member 3 |

| P11226 | MBL2 | mannose binding lectin 2 |

| P21912 | SDHB | succinate dehydrogenase complex iron sulfur subunit B |

| P07339 | CTSD | cathepsin D |

| P17405 | SMPD1 | sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1 |

| P14210 | HGF | hepatocyte growth factor |

| P16581 | SELE | selectin E |

| P16109 | SELP | selectin P |

| P09238 | MMP10 | matrix metallopeptidase 10 |

| P08254 | MMP3 | matrix metallopeptidase 3 |

| P12724 | RNASE3 | ribonuclease A family member 3 |

| P08253 | MMP2 | matrix metallopeptidase 2 |

| P35228 | NOS2 | nitric oxide synthase 2 |

| P51606 | RENBP | renin binding protein |

| O60909 | B4GALT2 | beta-1,4-galactosyltransferase 2 |

| P21554 | CNR1 | cannabinoid receptor 1 |

| P13945 | ADRB3 | adrenoceptor beta 3 |

| P08100 | RHO | rhodopsin |

| P01308 | INS | insulin |

| O00206 | TLR4 | toll like receptor 4 |

| Q08209 | PPP3CA | protein phosphatase 3 catalytic subunit alpha |

| P30711 | GSTT1 | glutathione S-transferase theta 1 |

| P19440 | GGT1 | gamma-glutamyltransferase 1 |

| P35968 | KDR | kinase insert domain receptor |

| P35916 | FLT4 | fms related tyrosine kinase 4 |

| P17948 | FLT1 | fms related tyrosine kinase 1 |

| P04049 | RAF1 | Raf-1 proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase |

| P42898 | MTHFR | methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase |

| P19838 | NFKB1 | nuclear factor kappa B subunit 1 |

| P20132 | SDS | serine dehydratase |

| P10745 | RBP3 | retinol binding protein 3 |

| P52757 | CHN2 | chimerin 2 |

| P17707 | AMD1 | adenosylmethionine decarboxylase 1 |

| P04179 | SOD2 | superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial |

| Q09472 | EP300 | E1A binding protein p300 |

Key targets and signaling pathway of THSWD against DR

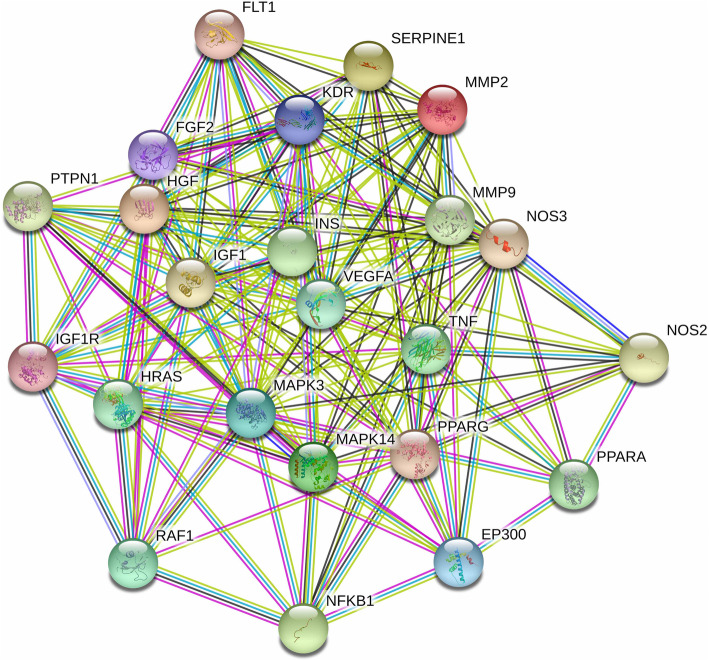

Core targets in protein-protein interaction (PPI)

The 67 candidate targets mentioned above were imported into STRING database to build the PPI network. According to the screening criteria of the confidence score above 0.9 and the degree score above the average value, 23 core targets were filtered out, including VEGFA, TNF, IGF1, INS, MAPK3, NFKB1, EP300, HRAS, FGF2, HGF, IGF1R, KDR, MAPK14, MMP9, MMP2, PPARA, RAF1, FLT1, NOS2, NOS3, PPARG, PTPN1 and SERPINE1 (Fig. 3). These 23 core targets may be used as valuable targets in the treatment of THSWD against DR and deserve further study.

Fig. 3.

PPI network of 23 core targets of THSWD against DR. In the PPI diagram, each solid circle represents a target, and the middle of the circle shows the structure of the protein

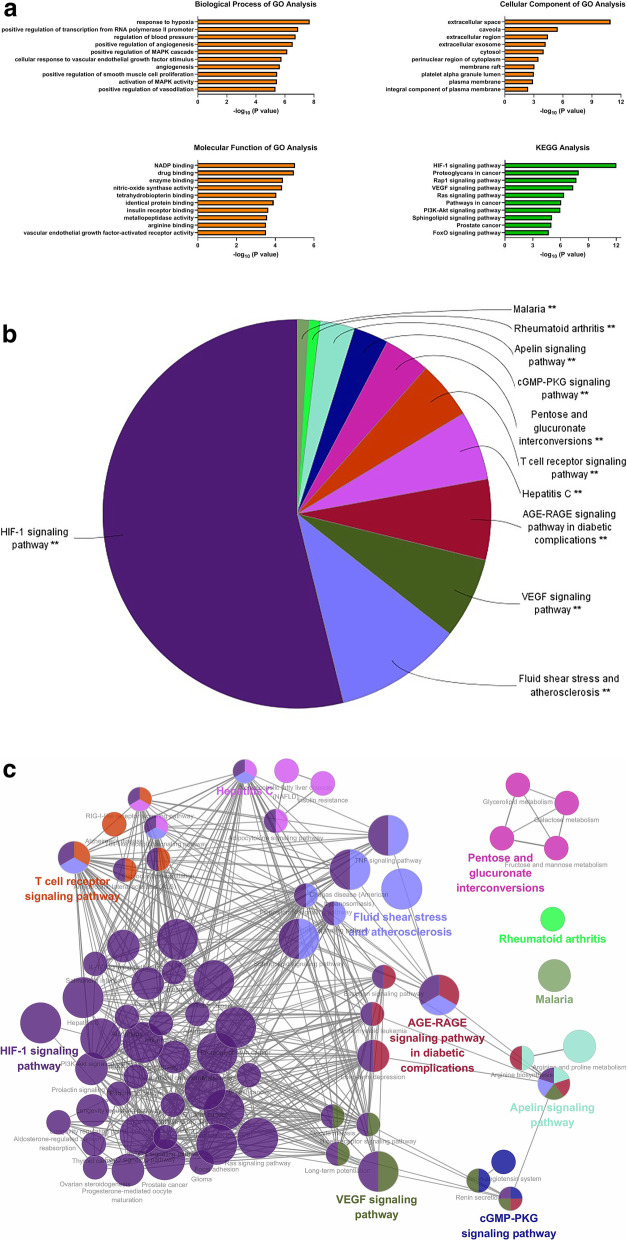

Functional enrichment of GO terms and KEGG pathways

Subsequently, the 67 candidate targets were imported into DAVID database to perform the functional enrichment analysis. The significant changed GO terms and KEGG pathways were evaluated based on the P value (Fig. 4a). The top three GO terms of biological process were response to hypoxia, positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter, and regulation of blood pressure. The top three GO terms of cellular component were extracellular space, caveola, and extracellular region. The top three GO terms of molecular function were NADP binding, drug binding, and enzyme binding. The top three KEGG pathways were HIF-1 signaling pathway, proteoglycans in cancer, and rap1 signaling pathway. From the analysis results of biological process and signaling pathway, we speculated that hypoxia response and hypoxia-related HIF-1 signaling pathway might be the important molecular mechanisms of THSWD against DR.

Fig. 4.

Functional enrichment of GO terms and KEGG pathways from DAVID and ClueGo. a GO terms and KEGG pathways from DAVID. b The pie chart from ClueGo. It shows the enriched signaling pathway categories based on the kappa coefficient, including HIF-1 signaling pathway, fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis, VEGF signaling pathway, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, hepatitis C, T cell receptor signaling pathway, pentose and glucoronate interconversions, cGMP-PKG signaling pathway, apelin signaling pathway, rheumatoid arthritis, and malaria. c The functional enrichment network from ClueGo. The node represents the signaling pathway, and the size of each node represents the enrichment significance of each signaling pathway. The larger the node is, the more significant the pathway is. The line represents the correlation between functions, and the thickness of each line represents the kappa coefficient between functions. The thicker the line is, the greater the kappa coefficient is

On the other hand, the 67 candidate targets were further imported into ClueGo plug-in to perform KEGG pathway analysis. As shown in Fig. 4b and c, signaling pathways were divided into 11 enriched categories based on the kappa coefficient, including HIF-1 signaling pathway, fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis, VEGF signaling pathway, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, and so on. We found that HIF-1 signaling pathway was the most significant enriched category. It further indicated that HIF-1 signaling pathway played a vital role in the treatment of THSWD against DR.

Core signaling pathway network of THSWD against DR

Considering the importance of HIF-1 signaling pathway in the treatment of THSWD, we further analyzed the targets and active ingredients of THSWD against DR in HIF-1 signaling pathway. There were 14 targets found in HIF-1 signaling pathway, including EP300, FLT1, GAPDH, HMOX1, IGF1, IGF1R, INS, MAPK3, NFKB1, NOS2, NOS3, SERPINE1, TLR4 and VEGFA, which were labelled as red in Fig. 5a. Notably, except for HMOX1 and TLR4, the other 12 targets all belonged to the core target group obtained from PPI network above (Fig. 3), which further proved the important role of HIF-1 signaling pathway. In addition, as shown in Fig. 5a, more targets of THSWD against DR focused on the effect of angiogenesis and vascular tone, which were closely related to DR.

Fig. 5.

The core HIF-1 signaling pathway in THSWD against DR. a The KEGG pathway of HIF-1 signaling pathway. The targets of THSWD against DR were labelled as red. b The “herb-ingredient-target” network of HIF-1 signaling pathway. The red square represents herbs in THSWD, the green triangle represents active ingredients of those herbs, and the orange circle represents targets of THSWD against DR. The size of each node represents the correlation degree with other nodes, and the larger the node is, the stronger the correlation is

Subsequently, the “herb-ingredient-target” network of HIF-1 signaling pathway was analyzed by Cytoscape software. According to the screening criteria of the degree score above the average value, the core network was filtered out (Fig. 5b). The core targets in HIF-1 signaling pathway were IGF1R, VEGFA, MAPK3, IGF1, SERPINE1, GAPDH, NOS2, NOS3, FLT1, HMOX1, TLR4 and INS. The core active ingredients were beta-sitosterol, baicalin, albiflorin, cholesterol, wallichilide, senkyunone, paeoinflorin, stigmasterol, pyrethrin II, carthamone, lactiflorin and campesterol. THSWD might alleviate the symptoms of DR via those core active ingredients and targets.

The influence of THSWD on key molecules of HIF-1 signaling pathway

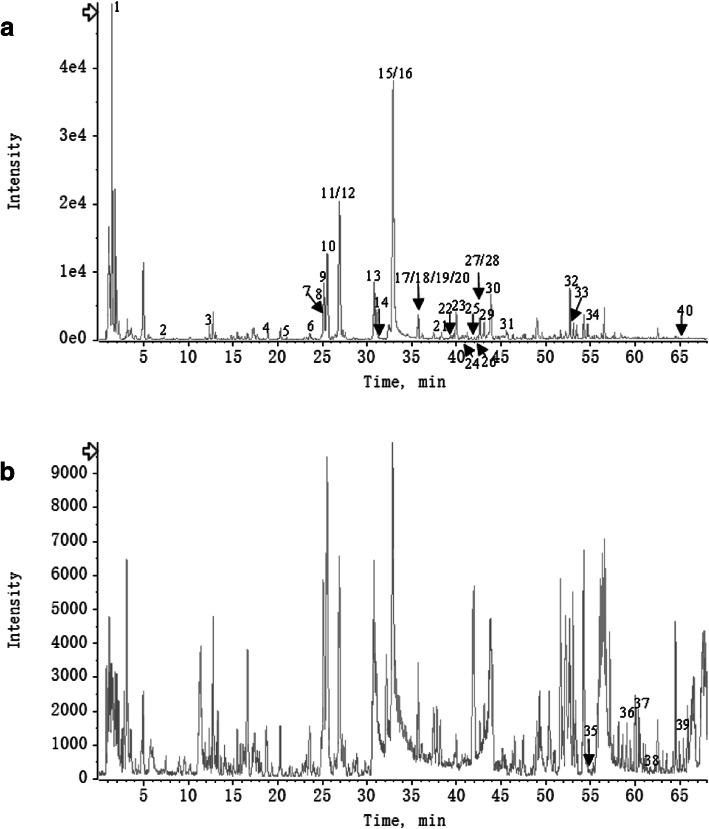

Quality control of THSWD

THSWD was analyzed by LC/MS in negative and positive-ion mode (Fig. 6a and b). Based on the database of Natural Products HR-MS/MS Spectral Library and the relevant references, 40 compounds were identified in THSWD (Supplementary Table 4). These results provided the scientific basis for other researchers to explore the ingredients and mechanisms of THSWD in further studies.

Fig. 6.

LC/MS chromatogram of THSWD in negative and positive mode (a and b)

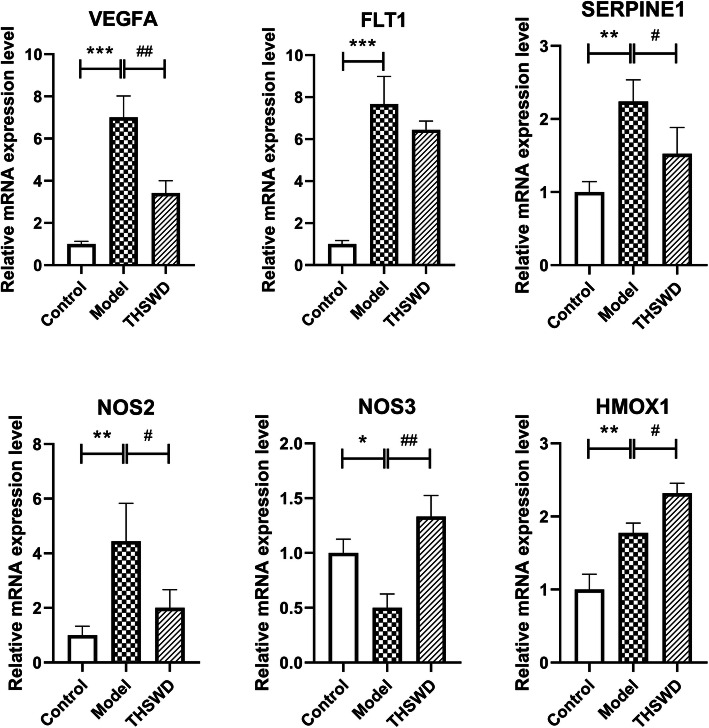

Changes of expression levels of key molecules in THSWD against DR

Compared with control group, the mRNA expression levels of VEGFA, FLT1, SERPINE1, NOS2 and HOMX1 were significantly up-regulated in model group (P < 0.01), and NOS3 was significantly down-regulated (P < 0.05). Compared with model group, the mRNA expression levels of VEGFA, SERPINE1 and NOS2 were significantly down-regulated in THSWD group (P < 0.05), and NOS3 and HMOX1 were significantly up-regulated (P < 0.05). (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Relative mRNA expression levels of key genes in THSWD against DR. All data were measured by qRT-PCR. GAPDH was used as the internal control. N = 3 in each group. Values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc test. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 (vs. control group); # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, ### P < 0.001 (vs. model group)

Discussion

DR is caused by microangiopathy and capillary closure, which results in the breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier with retinal hemorrhage, exudate and edema formation, and macular edema [24]. Several studies have reported that THSWD had a good clinical effect on the treatment of DR. [13] However, fewer researches could explain the mechanism of THSWD against DR at the molecular level. In our study, according to network analysis and experimental validation, we found that HIF-1 signaling pathway and some related targets were mainly involved in the treatment of THSWD against DR.

The normal microvessel wall is based on the basement membrane. Hyperglycemia induces injury to vascular endothelial cells, which leads to progressive thickening of the basement membrane and obstruction of the involved microvascular, thus resulting in tissue hypoxia and increased lesions [25]. Retinal hypoxia is a common factor in the development of DR. [26] Hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) is dysregulated following hypoxia [27]. HIF-1 is the transcription factor that improves hypoxia adaptation and plays an important functional role in a wide range of ischemic and inflammatory diseases [28]. Previous studies have reported that suppressing HIF-1 signaling pathway could contribute to the remission of DR. [29, 30] From our results, the pharmaceutical mechanism of THSWD against DR might be associated with the suppression of HIF-1 signaling pathway.

Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) was the core targets of THSWD against angiogenesis of DR via HIF-1 signaling pathway from our results. Hypoxia is the most important trigger for VEGF upregulation mainly through HIF-1 [31]. VEGF is a highly potent proangiogenic agent which induces retinal angiogenesis, the major pathological characteristics of DR. [32] Previous studies have reported that some core active ingredients we found in HIF-1 pathway (Fig. 6b) could regulate the expression of VEGF. For example, some researchers proved that baicalin [33, 34], paeoniflorin [35–38] and stigmasterol [39] reduced the expression of VEGF and had a powerful effect on anti-angiogenesis, which were consistent with our findings.

Serpin family E member 1 (SERPINE1; plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, PAI1) was another core targets of THSWD against angiogenesis. SERPINE1, the inhibitor of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), participates in the processes of VEGF-initiated angiogenesis by promoting the migration of endothelial cells [40]. It has been reported that SERPINE1 expression was upregulated in the retina of mice with retinopathy and angiogenesis significantly alleviated in SERPINE1-knockdown mice [41]. Baibalin [42] and paeoniflorin [43] have been proved to inhibit the production of SERPINE1, but the researches mainly focused on antithrombotic and antifibrotic activities.

Nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2; inducible NOS, iNOS) and nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3; endothelial NOS, eNOS) were also the core targets of THSWD against DR in HIF-1 signaling pathway. NOS are enzymes that catalyze the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline and nitric oxide (NO) [44], a small free radical with critical signaling roles in physiology and pathophysiology [45]. In different circumstances, NOS enzyme expression and function are highly specific to each isoform. NOS2/iNOS is not expressed under normal conditions, while in human immune responses, NOS2 expression will be induced by proinflammatory cytokines. NOS3/eNOS is expressed almost exclusively in the endothelium under basal conditions, while in hypoxia, the expression will reduce, which further influences vascular tone, hemostasis and angiogenesis [46]. A long-standing challenge for researchers in the NOS field has been to provide plausible mechanism to explain opposite biological responses to NO under seemingly similar circumstances resulting from the complex mechanisms of NO. In fact, differences in tissue O2 concentrations will partially determine the expressions of NOS enzymes and the steady-state concentration of NO, subsequently dictating what cellular targets interacted with. The types and distributions of cellular targets will determine cell phenotype, ultimately leading to positive or negative effects on disease outcome [47]. In our study, the expression of NOS2 mRNA was significantly down-regulated in THSWD group compared to model group, while the expression of NOS3 mRNA was significantly up-regulated in THSWD group. However, the concentration of NO and further biological responses to NO did not be detected. Thus, the effects and mechanisms of THSWD on NOS enzymes need to be further explored.

In addition, heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1) was also the targets of THSWD against DR in HIF-1 signaling pathway. HMOX1 is an intracellular enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of heme to generate carbon monoxide (CO), ferrous iron, and biliverdin, which is subsequently converted to bilirubin. These products can display multiple actions, including anti-oxidation, anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis [48]. Under basal conditions, HMOX1 is expressed at low levels in most tissues, while in response to various pathophysiological stresses/stimuli, the expression will be highly induced. Thus, HMOX1 induction is thought to be an adaptive defense mechanism in order to protect the human body against injury in many disease situations [49]. From our results, HMOX1 was found significantly up-regulated by THSWD. Previous study reported that beta-sitosterol, one core active ingredient of THSWD, could enhance the expression of HMOX1 [50]. It suggested that THSWD and its ingredients might play a protective role in DR via regulating the expression of HMOX1.

Conclusions

Taken together, this study uncovered the multi-ingredient and multi-target mechanisms of THSWD against DR by combining network analysis and experimental validation. It was found that THSWD was capable of regulating HIF-1 signaling pathway and other important pathways, and had powerful effects of anti-angiogenesis, anti-oxidation and so on. This study explained the complex ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms of THSWD, and identified potential therapeutic targets and signaling pathways, which could provide a theoretical basis for the application of THSWD and the development of new drugs for the treatment of DR.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Sixty one active ingredients found in Taohong Siwu decoction (THSWD) after overlapped ingredients were subtracted. The active ingredients were obtained from Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) database (http://lsp.nwu.edu.cn/tcmsp.php) according to meeting the criteria of oral bioavailability (OB ≥ 30%) and drug-likeness (DL ≥ 0.18). Table S2. Two thousand three hundred forty targets of active ingredients of THSWD. The targets were identified using ChemMapper database (http://lilab.ecust.edu.cn/chemmapper/) according to the criteria of 3D structure similarity above 0.85 and prediction score above 0 and PharmMapper (http://lilab.ecust.edu.cn/pharmmapper/index.php) databases according to the target pharmacophore approach. Table S3. Two hundred sixty three diabetic retinopathy (DR)-associated genes. DR-associated genes were searched from DisGeNET database (http://www.disgenet.org/web/DisGeNET/menu/home), DrugBank database (https://www.drugbank.ca/), and Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (https://db.idrblab.org/ttd/). Table S4. Characterization of chemical constituents of THSWD by UPLC–ESI-Q-TOF/MS.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BS

Baishao, Paeoniae Radix Alba

- CO

Carbon monoxide

- CX

Chuangxiong, Chuanxiong Rhizoma

- DG

Ganggui, Angelicae Sinesis Radix

- DR

Diabetic retinopathy

- GO

Gene ontology

- HH

Honghua, Carthami Flos

- HIF-1

Hypoxia inducible factor-1

- HMOX1

Heme oxygenase 1

- hRMECs

Human retinal microvascular endothelial cells

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LC/MS

Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NOS2

nitric oxide synthase 2

- NOS3

nitric oxide synthase 3

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- SD

Standard deviation

- SDH

Shudihuang, Rehmanniae Radix Praeparata

- SERPINE1

serpin family E member 1

- TCM

Traditional Chinese medicine

- TCMSP

Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology

- THSWD

Taohong Siwu decoction

- TR

Taoren, Persicae Semen

- TTD

Therapeutic Target Database

- uPA

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Authors’ contributions

LZ and WM conceived the experiments. LW and KL conducted the experiments. LW, SL, LLW and JD analyzed the data. LW wrote the paper. LZ and WM revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by grants from Talents Training Program of Pudong Health Commission of Shanghai (No. PWRd2018–09), Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (No.201740052), Science and Technology Development Fund of Shanghai Pudong New Area (No. PKJ2018-Y16), Budgetary fund of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2020TS098), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81703791). All the above funds provided financial support for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Supplementary materials.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lei Wang and Shuyan Li contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Wanhong Miao, Email: sgmwh123@126.com.

Lei Zhang, Email: qyzl1967@163.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12906-020-03086-0.

References

- 1.Wong TY, Cheung CM, Larsen M, Sharma S, Simo R. Diabetic retinopathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16012. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flaxman SR, Bourne RRA, Resnikoff S, Ackland P, Braithwaite T, Cicinelli MV, et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990-2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(12):e1221–e1e34. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rees G, Xie J, Fenwick EK, Sturrock BA, Finger R, Rogers SL, et al. Association between diabetes-related eye complications and symptoms of anxiety and depression. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(9):1007–1014. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Singh RP. The role of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) in the management of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212532. doi: 10.7573/dic.212532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitcup SM, Cidlowski JA, Csaky KG, Ambati J. Pharmacology of corticosteroids for diabetic macular edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(1):1–12. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-22259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song SJ, Han K, Choi KS, Ko SH, Rhee EJ, Park CY, et al. Trends in diabetic retinopathy and related medical practices among type 2 diabetes patients: results from the National Insurance Service Survey 2006-2013. J Diabetes Investig. 2018;9(1):173–178. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung N, Wong IY, Wong TY. Ocular anti-VEGF therapy for diabetic retinopathy: overview of clinical efficacy and evolving applications. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):900–905. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capitao M, Soares R. Angiogenesis and inflammation crosstalk in diabetic retinopathy. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117(11):2443–2453. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang D, Lv FL, Wang GH. Effects of HIF-1alpha on diabetic retinopathy angiogenesis and VEGF expression. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(16):5071–5076. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201808_15699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Kharashi AS. Role of oxidative stress, inflammation, hypoxia and angiogenesis in the development of diabetic retinopathy. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2018;32(4):318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hautala N, Aikkila R, Korpelainen J, Keskitalo A, Kurikka A, Falck A, et al. Marked reductions in visual impairment due to diabetic retinopathy achieved by efficient screening and timely treatment. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92(6):582–587. doi: 10.1111/aos.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo ZR, Li H, Xiao ZX, Shao SJ, Zhao TT, Zhao Y, et al. Taohong Siwu decoction exerts a beneficial effect on cardiac function by possibly improving the microenvironment and decreasing mitochondrial fission after myocardial infarction. Cardiol Res Pract. 2019;2019:5198278. doi: 10.1155/2019/5198278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao XC, Gong YY. Clinical observation for the adjuvant therapy of modified Taohong Siwu decoction on nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. J Pract Trad Chin Med. 2019;35(9):1133–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ru J, Li P, Wang J, Zhou W, Li B, Huang C, et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J Chem. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Zhang Y, Liu YM, Yang XC, Chen YY, Wu GJ, et al. Uncovering the protective mechanism of Huoxue Anxin recipe against coronary heart disease by network analysis and experimental validation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;121:109655. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong J, Cai C, Liu X, Ku X, Jiang H, Gao D, et al. ChemMapper: a versatile web server for exploring pharmacology and chemical structure association based on molecular 3D similarity method. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(14):1827–1829. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Shen Y, Wang S, Li S, Zhang W, Liu X, et al. PharmMapper 2017 update: a web server for potential drug target identification with a comprehensive target pharmacophore database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W356–WW60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinero J, Ramirez-Anguita JM, Sauch-Pitarch J, Ronzano F, Centeno E, Sanz F, et al. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D845–DD55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, Lo EJ, Marcu A, Grant JR, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1074–D1D82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Zhang S, Li F, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Wang Z, et al. Therapeutic target database 2020: enriched resource for facilitating research and early development of targeted therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D1031–D1D41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, Kuhn M, Wyder S, Simonovic M, et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D362–D3D8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4(5):P3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-5-p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nentwich MM, Ulbig MW. Diabetic retinopathy - ocular complications of diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(3):489–499. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i3.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.La Sala L, Cattaneo M, De Nigris V, Pujadas G, Testa R, Bonfigli AR, et al. Oscillating glucose induces microRNA-185 and impairs an efficient antioxidant response in human endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:71. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0390-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez ML, Perez S, Mena-Molla S, Desco MC, Ortega AL. Oxidative stress and microvascular alterations in diabetic retinopathy: future therapies. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:4940825. doi: 10.1155/2019/4940825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu N, Zhao N, Chen L, Cai N. Survivin contributes to the progression of diabetic retinopathy through HIF-1alpha pathway. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(8):9161–9167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wert KJ, Mahajan VB, Zhang L, Yan Y, Li Y, Tosi J, et al. Neuroretinal hypoxic signaling in a new preclinical murine model for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2016;1:16005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Ding H, Chen B, Lu Q, Wang J. Profilin-1 mediates microvascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetic retinopathy through HIF-1alpha-dependent pathway. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11(3):1247–1255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang H, He J, Johnson D, Wei Y, Liu Y, Wang S, et al. Deletion of placental growth factor prevents diabetic retinopathy and is associated with Akt activation and HIF1alpha-VEGF pathway inhibition. Diabetes. 2015;64(1):200–212. doi: 10.2337/db14-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simo R, Sundstrom JM, Antonetti DA. Ocular anti-VEGF therapy for diabetic retinopathy: the role of VEGF in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):893–899. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Behl T, Kotwani A. Chinese herbal drugs for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;69(3):223–235. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jo H, Jung SH, Yim HB, Lee SJ, Kang KD. The effect of baicalin in a mouse model of retinopathy of prematurity. BMB Rep. 2015;48(5):271–276. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.5.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang M, Kan L, Wu L, Zhu Y, Wang Q. Effect of baicalin on renal function in patients with diabetic nephropathy and its therapeutic mechanism. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17(3):2071–2076. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan R, Shi W, Xin Q, Yang B, Hoi MP, Lee SM, et al. Tetramethylpyrazine and Paeoniflorin inhibit oxidized LDL-induced angiogenesis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells via VEGF and notch pathways. Evidence-Based Complem Altern Med. 2018;2018:3082507. doi: 10.1155/2018/3082507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abd El-Aal NF, Abdelbary EH. Paeoniflorin in experimental BALB/c mansoniasis: a novel anti-angiogenic therapy. Exp Parasitol. 2019;197:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song S, Xiao X, Guo D, Mo L, Bu C, Ye W, et al. Protective effects of Paeoniflorin against AOPP-induced oxidative injury in HUVECs by blocking the ROS-HIF-1alpha/VEGF pathway. Phytomedicine. 2017;34:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H, Wang J, Wang J, Wang P, Xue Y. Paeoniflorin attenuates Abeta1-42-induced inflammation and chemotaxis of microglia in vitro and inhibits NF-kappaB- and VEGF/Flt-1 signaling pathways. Brain Res. 2015;1618:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michelini FM, Lombardi MG, Bueno CA, Berra A, Sales ME, Alche LE. Synthetic stigmasterol derivatives inhibit capillary tube formation, herpetic corneal neovascularization and tumor induced angiogenesis: Antiangiogenic stigmasterol derivatives. Steroids. 2016;115:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breuss JM, Uhrin P. VEGF-initiated angiogenesis and the uPA/uPAR system. Cell Adh Migr. 2012;6(6):535–615. doi: 10.4161/cam.22243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basu A, Menicucci G, Maestas J, Das A, McGuire P. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) facilitates retinal angiogenesis in a model of oxygen-induced retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(10):4974–4981. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee W, Ku SK, Bae JS. Antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and profibrinolytic activities of baicalin. Arch Pharm Res. 2015;38(5):893–903. doi: 10.1007/s12272-014-0410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng J, Dou Y, Guo J, Wu X, Dai Y. Paeoniflorin of Paeonia lactiflora prevents renal interstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction in mice. Phytomedicine. 2013;20(8–9):753–759. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stuehr DJ, Haque MM. Nitric oxide synthase enzymology in the 20 years after the Nobel prize. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(2):177–188. doi: 10.1111/bph.14533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tejero J, Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Sources of vascular nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species and their regulation. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(1):311–379. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho JJ, Man HS, Marsden PA. Nitric oxide signaling in hypoxia. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012;90(3):217–231. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0880-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas DD. Breathing new life into nitric oxide signaling: a brief overview of the interplay between oxygen and nitric oxide. Redox Biol. 2015;5:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maamoun H, Benameur T, Pintus G, Munusamy S, Agouni A. Crosstalk between oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in endothelial dysfunction and aberrant angiogenesis associated with diabetes: a focus on the protective roles of Heme Oxygenase (HO)-1. Front Physiol. 2019;10:70. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kishimoto Y, Kondo K, Momiyama Y. The protective role of Heme Oxygenase-1 in atherosclerotic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(15):3628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Yin Y, Liu X, Liu J, Cai E, Zhu H, Li H, et al. Beta-sitosterol and its derivatives repress lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine-induced acute hepatic injury by inhibiting the oxidation and inflammation in mice. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28(9):1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Sixty one active ingredients found in Taohong Siwu decoction (THSWD) after overlapped ingredients were subtracted. The active ingredients were obtained from Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) database (http://lsp.nwu.edu.cn/tcmsp.php) according to meeting the criteria of oral bioavailability (OB ≥ 30%) and drug-likeness (DL ≥ 0.18). Table S2. Two thousand three hundred forty targets of active ingredients of THSWD. The targets were identified using ChemMapper database (http://lilab.ecust.edu.cn/chemmapper/) according to the criteria of 3D structure similarity above 0.85 and prediction score above 0 and PharmMapper (http://lilab.ecust.edu.cn/pharmmapper/index.php) databases according to the target pharmacophore approach. Table S3. Two hundred sixty three diabetic retinopathy (DR)-associated genes. DR-associated genes were searched from DisGeNET database (http://www.disgenet.org/web/DisGeNET/menu/home), DrugBank database (https://www.drugbank.ca/), and Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (https://db.idrblab.org/ttd/). Table S4. Characterization of chemical constituents of THSWD by UPLC–ESI-Q-TOF/MS.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Supplementary materials.