Abstract

The US public health community has demonstrated increasing awareness of rural health disparities in the past several years. Although current interest is high, the topic is not new, and some of the earliest public health literature includes reports on infectious disease and sanitation in rural places. Continuing through the first third of the 20th century, dozens of articles documented rural disparities in infant and maternal mortality, sanitation and water safety, health care access, and among Black, Indigenous, and People of Color communities. Current rural research reveals similar challenges, and strategies suggested for addressing rural–urban health disparities 100 years ago resonate today. This article examines rural public health literature from a century ago and its connections to contemporary rural health disparities. We describe parallels between current and historical rural public health challenges and discuss how strategies proposed in the early 20th century may inform current policy and practice. As we explore the new frontier of rural public health, it is critical to consider enduring rural challenges and how to ensure that proposed solutions translate into actual health improvements. (Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1678–1686. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305868)

“In rural districts, medical attention is not as a rule so easily available as in the cities, partly because of the long distances, partly because of poor roads, partly for other reasons, and in general the same standard of medical attention is relatively more expensive; free clinics are practically unknown, district nursing almost unheard of and hospital advantages rare, as compared with these advantages in the cities.”

—C. W. Stiles, “The Rural Health Movement,” 19111

In recent years, the US public health community has expressed increasing concern over disparities in rural health, particularly following studies that revealed a widening rural–urban gap in life expectancy and higher rural preventable death rates.2 Subsequently, rural health–related research has grown, and those new to the field have joined career rural health researchers in documenting rural health disparities in social determinants of health, health status, health care access, disease prevalence, morbidity, and mortality. Although current interest in rural health is high, these topics are not new to public health. Established in 1911, the American Journal of Public Health published a report in 1912 calling typhoid in rural areas “the greatest problem of sanitation in the United States.”3 In the Journal’s first five years, more than 10 articles focused specifically on rural health issues4; other academic journals were simultaneously reporting on the health of rural populations.5

Over the next two decades, dozens of articles documented rural disparities in infant and maternal mortality, sanitation and water safety, health care access, and minority health. Current rural health research reveals many similar disparities, and modern rural health advocates recognize the conditions described in the quotation introducing this article. Maternal mortality rates are increasing, particularly among Black rural women. The opioid epidemic has shown how HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) could spread rapidly through a rural community. Access to medical care and inequities experienced by racial and ethnic minorities are enduring rural phenomena. Many historical public health delivery challenges and strategies for addressing rural–urban health disparities also resonate today.

This article examines rural public health literature from 1900 to the 1930s and its parallels to current rural health. As we explore the new frontier of rural public health, it is critical to consider the enduring challenges rural populations face and how to ensure that proposed solutions translate into actual health improvements. Given the breadth of these challenges, we do not delve deeply into any individual issue, but provide multiple snapshots of rural health in the early 20th century and their current corollaries. Readers may consult our numerous references for further detail on individual topics. Additionally, we do not confine ourselves to a single, technical definition of rurality. As described in the “Definitions and Data” section, not only have definitions evolved over time, but current federal agencies may categorize different communities as rural. Rather than affirm any single classification, we acknowledge varied rural definitions, accept the term as used in each article cited, and generally consider rural communities to be those with small populations, low density, and limited proximity to the resources of urban centers.

IDENTIFICATION OF RURAL HEALTH DISPARITIES

In the early 20th century, multiple examples of rural health disparities emerged in the public health literature, including infectious disease, maternal and child health, health care access, and racial health inequities.

Infectious Disease

Early US public health emphasized both infectious disease and the health of urban populations. An 1850 report noted that the causes of “premature and preventable” death and sickness “are active in all the agricultural towns, but press most heavily upon cities.”6 The American Public Health Association, founded in 1872, focused initially on city hygiene and safety. Yet, as urban public health led to sanitation improvements, rural efforts lagged behind, and numerous early articles documented rural outbreaks of infectious disease.7 For example, as urban typhoid mortality declined in the early 1900s, eventually falling below rural rates, rural outbreaks were slow to garner attention: “These aggregate figures are startling, yet one rarely hears of rural epidemics for the population is so scattered and the total number of deaths for a given area so small in comparison to the city.”8

Overall, 20th-century public health achievements in sanitation and immunization led to prolonged life expectancy and a shift in the three leading causes of death from infectious disease (pneumonia and influenza, tuberculosis, and diarrhea) in 1900 to noncommunicable disease (heart attack, cancer, and stroke) in 1999.9 Yet, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, areas of alarm for rural infectious disease had emerged. Opioid-related injection drug use contributed to new HIV and HCV infections in isolated rural communities such as Scott County, Indiana,10 with similar outbreaks in other rural communities.11 Analyses suggest that most communities vulnerable to the rapid spread of HIV or HCV among people who inject drugs are rural.12 Concerns about rural immunization rates, particularly for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, suggest that rural residents face other vulnerabilities to infectious disease.13 Although urban areas were hardest hit by the first COVID-19 wave, by May 2020, rural increases in infection rates and death were outpacing urban increases.14

Maternal and Child Health

In 1915, the maternal mortality rate was 607.9 per 100 000 live births,15 and one in 10 infants did not live to be a year old.16 As with infectious disease, the effectiveness of early maternal and infant health campaigns was largely limited to urban areas.17 A study examining infant mortality from 1910 to 1913 found that whereas cities showed a “marked reduction,” infant mortality in rural areas had increased.18 Statistics were even worse when racial disparities were considered. Speaking to the National Medical Association in 1917, D. W. Byrd noted that Black infant and maternal mortality was twice that of Whites. He remarked, “If … infant mortality is an index of social welfare and sanitary advancement … this great country has been shamefully neglectful in things most vital.”19

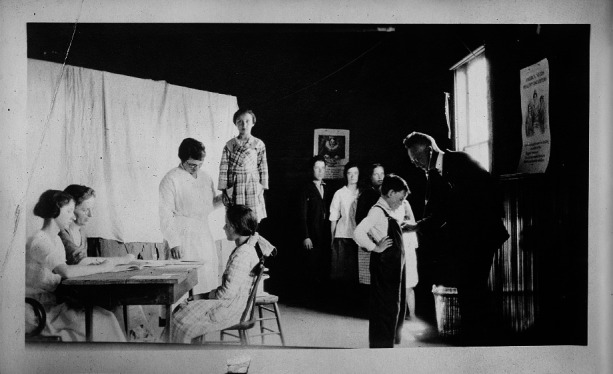

School Doctor’s Visit, Vermont, 1924

Source. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, American National Red Cross Collection, LC-DIG-anrc-15197.

One hundred years later, after decades of decline, US maternal morbidity and mortality rates are rising,20 and rural mothers are at increased risk for severe adverse outcomes—especially Black women in the rural South.21 Rural counties have elevated infant mortality rates: 6.69 per 100 000, compared with 5.49 per 100 000 in large urban counties.22 These disparities may be exacerbated by worsening access to care for pregnant and postpartum rural women. From 2004 to 2014, 9% of rural counties experienced hospital obstetric unit closures, leaving more than half of rural counties without such services.23 Differences in obstetric availability mean that rural women, especially in lower-income counties, must travel farther for obstetric care.24

Health Care Access

The early 20th century saw a rise in public health agencies delivering personal health care services, including home visiting programs, tuberculosis clinics, and school clinics.25 During the 1920s and 1930s, the federal government took an increasing role in ensuring the availability of, and access to, services for multiple conditions and populations.26 Accompanying, and in some cases encouraging, this focus was growing awareness that rural populations faced unique access barriers, including insufficient health care professionals, facilities, and resources. The 1921 Sheppard–Towner Act, which provided states with federal funding for prenatal and infant health home visits, was influenced by concern over rural service availability. Similarly, a 1929 article called for improved methods to assess the sufficiency and efficiency of rural health services,27 and another study used administrative data to document the decline of physicians practicing in rural areas between 1922 and 1938.28

Themes of insufficient providers, including facilities, resonate among rural health experts today along with other health care access issues, including transportation barriers, socioeconomic barriers like lower education and health literacy, and higher uninsured and underinsured rates.29 These concerns are rising as the rural United States has experienced an alarming hospital closure rate: 129 have closed since 2010.30 As noted in the previous section, even when hospitals remain open they may close critical services such as obstetric care. Other provider shortages also contribute to disparate rural health care access; in 2019, 64% of nonmetropolitan counties were designated primary care Health Professional Shortage Areas, compared with 41% of metropolitan counties.31

Racial Health Inequity

Although more limited than reports on general rural health disparities, some early literature describes concern for rural People of Color, particularly southern Blacks and Indigenous people. A 1911 report described disparities faced by Native Americans, including overall mortality rates 60% higher than for Whites and tuberculosis death rates nearly three times higher.32 In 1916, the assistant surgeon general noted that whereas mortality disparities between White and “colored” residents were most striking in urban populations, similar disparities were prevalent in rural communities.33 A 1915 Georgia State Board of Health report described concern for diseases such as hookworms and typhoid among Black rural residents and noted that urban data and solutions were unlikely to be of help.34 Other reports from that period noted elevated maternal and child mortality rates among Black rural residents.35

Many rural Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities continue to experience poorer health status, access, and outcomes compared with rural Whites.36 Yet contemporary research has earned criticism for too frequently ignoring the heterogeneity of rural communities, including differences in racial and ethnic composition and corresponding outcomes.37 Although many view rural–urban health disparities as synonymous with White poverty, and national analyses frequently support this perception, rural places are home to substantial and growing racial and ethnic diversity.38 For these groups, rural residence and racism often combine to exacerbate the health inequities experienced by their urban and White counterparts.39 Counties with majority BIPOC populations experience elevated mortality rates not explained by county socioeconomic characteristics, leading to conclusions that political and economic histories, including racism, must be considered when addressing rural health disparities among BIPOC communities.40

RURAL PUBLIC HEALTH DELIVERY CHALLENGES

Early rural public health delivery efforts faced multiple challenges that resonate with contemporary rural public health professionals. These included more limited resources and infrastructure, definition and data issues, and political resistance to public health activity.

Resources and Infrastructure

Early public health literature noted that differences in geography, population density, politics, workforce availability, and finance could impede rural versus urban program implementation. An 1894 report documented how rural diphtheria control was difficult because of wider geographic area, lack of medical infrastructure, distance to treatment facilities, and social isolation that slowed disease reporting.41 In 1914, S. A. Knopf indicated that social stigma may make rural disease detection more difficult and that rural areas may need different tuberculosis control approaches than urban areas because of “limited administrative machinery.”42 Other reports noted lags in rural public health development because small towns lacked the financial base to support public health infrastructure.43 Limited access to new treatments was also a problem according to a 1917 study: following antitoxin development, cities saw diphtheria mortality decline more than 75%, whereas rural rates fell only 25%.44 Even with access to new treatments, rural practitioners faced difficulties making timely diagnoses, leading to calls for establishing branch laboratories in rural districts to eliminate long transit times to urban laboratories and diagnostic delays.45

Rural health experts today note that rural public health infrastructure remains underdeveloped and underresourced. Compared with urban departments, rural health departments have less capacity to meet population health goals, less funding, and fewer trained public health professionals,46 and they are less likely to be accredited.47 Underlying these challenges is rural health departments’ reliance on state and federal public health funding, which has declined over the last decade.48 Additionally, workforce and funding shortages, coupled with poorer health outcomes in rural populations, lead to what Harris et al. call a “double disparity” for many rural local health departments.49

Definitions and Data

Historical articles describe challenges in rural definition and data collection as barriers to rural public health programming. Early literature critiques the use of dichotomous measures of rurality as “arbitrary statistical divisions of communities into two crude groups of ‘urban’ and ‘rural.’ ”50 Similarly, multiple reports in the early 20th century critiqued inaccurate reporting of rural mortality statistics as an epidemiological challenge to health improvement. For example, as maternity hospitalization became more common, rural infant and maternal mortality was generally underreported because many deaths occurred in urban hospitals and were added to urban totals.51 Articles expressed concern that these challenges might have been even greater for BIPOCs residing in rural places.52

Data access and challenges defining rurality remain ongoing issues. Out of privacy concerns, an increasing number of federal health data resources (e.g., the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, the National Health Interview Survey, and the National Survey of Children’s Health) have no publicly available rural–urban identifier, making it hard to document health disparities experienced by rural populations. Even when geographic indicators are available, rural samples may be too small to yield reliable results, particularly for subgroups, geographic units, or measures over time. This can lead to generalizations about rural health that may mask important differences between rural populations or regional areas. Finally, although rural definitions have expanded over the century, they are inconsistent across federal agencies and may impede our ability to implement effective public health programming and policy. For example, county-based classifications like Rural–Urban Continuum Codes and Urban Influence Codes can obscure rural communities within larger urban counties. Other definitions based on zip code (Frontier and Remote Area Codes) or census tract (Rural–Urban Commuting Areas) offer more nuanced views of rurality—including work and resource patterns—but are more challenging to update and rarely available in public health data resources.53

A Public Health Nurse on Her Rounds in the Mountains

Source. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, American National Red Cross Collection, LC-DIG-anrc-03297.

The Politics of Health

In the early 20th century, public health experts noted that rural political values could make public health activity particularly challenging. For example, one practitioner noted that “This lack of progress [in rural public health] has often been due to a certain civic pride which has defeated any attempt to change the old order of things or to cooperate with neighboring communities in promoting measures for the betterment of all concerned.”54 Reflecting a similar sentiment, another commentator posited that a more libertarian spirit among rural residents could account for some reluctance to embrace public health initiatives: “Many [rural men] … would consider an anti-spitting regulation an infringement on his inalienable rights as a free citizen.”55

Rural Agents and Nurse—The Booker T. Washington Agricultural School on Wheels, Madison County, Alabama, 1923

Source. National Archives, Historical File of the Office of Information, US Department of Agriculture.

A similar theme has appeared in current rural public health policy debates. For example, states with significant rural populations are less likely to engage in tobacco control and prevention policy.56 Rural school districts are less likely to provide comprehensive sexuality education compared with those in urban areas, and rural residents have been more reluctant to participate in HPV vaccination.57 Although Medicaid expansion through the Affordable Care Act resulted in larger improvements in health coverage for rural residents compared with urban populations,58 states with significant rural populations have been slower to adopt expansion, and many continue not to participate.59

The health of rural BIPOCs has undoubtedly been affected by our country’s political history and its reluctance to acknowledge structural racism as a driver of health disparities. For example, historical documents attribute health inequities among Black rural residents to poor education or character, with comments such as “Ignorance ... is responsible for many diseases [in] this race,”60 or suggestions that disparities reflected “lower moral and sanitary standards.”61 Even when causes such as poverty and housing were noted, public health failed to recognize racism as the source of unequal health. In the past 50 years, the public health profession has improved at identifying structural inequities in health, and eminent public health scholars have been explicit in identifying racism itself as a determinant. (See AJPH October 2019 for a retrospective on the health legacy of US slavery.) However, recognition of racism’s health impacts may be slower to diffuse into rural communities that are predominantly White. Public opinion surveys on attitudes about race in the United States suggest that rural residents are less likely to see differences in racial and ethnic outcomes as driven by racism versus individual decisions.62

RURAL SOLUTIONS AND INNOVATIONS

Many current strategies proposed to address rural–urban health disparities and public health system challenges mirror those proposed one hundred years ago. These include rural health district development, public health nursing, organizational partnerships, and engaging community members in health promotion.

Development of Rural Health Districts

Beyond documenting rural health challenges, early 20th-century public health officials recognized that urban public health approaches may not work in rural areas and identified innovative solutions. Historically, adapting public health administrative models to fit rural areas required a collaborative approach. Although health departments serving one municipality had been effective in larger cities, this model was cost-prohibitive and inefficient for most smaller towns.63 Public health officials 100 years ago called for development of rural health districts that could employ a public health officer and other staff to coordinate health activities serving multiple communities.64 The Committee on Rural Health Administration acknowledged that through such cooperative work, “local health units … profit through both the financial subsidy afforded and by greatly increased working efficiency.”65

Local health departments (LHDs) today may benefit from a similar cooperative approach. Resource sharing among LHDs may offer one solution to resource limitations, with cross-jurisdictional approaches allowing for greater provision of services to rural communities.66 In New York, for example, two rural counties have successfully reduced LHD personnel costs while simultaneously increasing staff expertise and access to federal resources through a shared staffing model. Other rural resource-sharing examples include a six-county environmental health initiative in Colorado, and Horizon Public Health, a merger of three LHDs serving five counties in west central Minnesota.67

Public Health Nursing

Historically, public health nurses (PHNs) were essential in delivering rural health services. According to one rural health department, “The public health administrator realizes that scarcely a wheel can turn in his health machinery without the nurse. To say that she is indispensable to the program does not cover the fact. To a great extent, her work is the program.”68 Rural PHNs often served large, geographically dispersed populations, fulfilling numerous and varied responsibilities, including home visiting, maternity and infant care, school nursing, and clinic service.69 Despite these challenges, PHNs made great strides in expanding health services to rural and remote locales. They often led expansion efforts themselves, as with Lillian Wald, the “mother of public health nursing,” who founded the American Red Cross Rural Nursing Service in 1912,70 and Mary Breckinridge, who established the Frontier Nursing Service in 1928.71

PHNs remain at the center of many LHDs today. Registered nurses are the second largest segment of the LHD workforce, although their numbers have been declining.72 Acknowledging PHNs’ importance, some rural states are investing in recruitment and training of PHNs and other health care workers. In Minnesota, the Department of Health offers loan forgiveness for PHNs working in designated high-need rural areas.73 Other states operate Rural Health Scholar programs that allow students in health professions to gain experience working in rural areas, with some offering programming for high school students.74 Where PHNs are able to provide rural-specific services—for example, with maternal and child home-visiting programs—they not only contribute to improved health outcomes but may also help build social and cultural capital in underserved and isolated rural communities.75

Financial support for training and recruiting PHNs was also a historical vehicle for addressing racial and ethnic disparities in rural health that may hold promise today. The National Health Circle for Colored People, established in 1919, was a Black-led organization charged with delivering public health services to underrepresented Southern Black communities.76 It included a scholarship fund and support from the US Public Health Service to train Black nurses and deploy them to remote communities. Graduates supported by the Circle provided essential public health services and promoted the nursing profession to the Black community. Similar investment in public health workforce development among BIPOC populations could yield both economic opportunities and increased diversity among public health practitioners, which is associated with better outcomes for those served and better hope for institutional equity.77 Current data suggest that growth in racial and ethnic diversity among public health graduates has been anemic in the past two decades, indicating an urgent need to reexamine our systems of public health education.78

Community Organizations as Partners

At the center of rural life, community organizations—especially schools—were recognized by many public health officials as critical partners in health promotion. Although inadequate preventive health measures could put schools in the middle of disease outbreaks, schools also presented an opportunity for public health monitoring and “instruction of future citizens about essential standards of personal and community hygiene and health.”79 Other community organizations were also historically recognized for their important role in developing and promoting rural public health services, and public health officials were encouraged to engage with churches, farm associations, women’s groups, labor unions, and chambers of commerce, among others.80

Rural community organizations’ potential to improve population health is still very real. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognizes that schools are important partners in public health, and their Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model calls for collaboration between schools, the health sector, and the communities they serve.81 Some rural communities and schools have implemented trauma-informed models of care to address the disparities in adverse childhood experiences faced by rural children.82 Outside of schools, rural public health professionals continue to engage with other community partners; examples of creative health promotion programs can be found at churches, food pantries, libraries, Cooperative Extensions, and elsewhere.83

Community Members in Health Promotion

Another historical approach to engage rural communities was the use of laypeople in public health work. According to one commentator, effective public health service required the ability to “enter into community life and be sympathetic with it.”84 Engaging community members directly in rural health service work was seen as a way to develop a shared sense of community responsibility for public health85 while simultaneously addressing workforce and financial challenges. A 1932 AJPH article recommended that “in order that the public dollar may go as far as possible, professional workers should ascertain the minimum number of procedures that they must carry on personally, and turn over all others to competent citizens.”86 Volunteers provided assistance to public health departments in numerous ways: offering transportation in hard-to-reach rural areas, collecting resources and funds, providing administrative assistance, and promoting the department’s work to friends and neighbors.87

The idea of engaging community members in rural public health work finds a parallel today in the role of community health workers (CHWs). Though not volunteers, CHWs are trained frontline public health workers who are typically members of the communities they serve.88 Like early public health lay workers, CHWs perform a variety of tasks, such as providing health education and counseling, assisting with health system navigation, connecting patients to social services and supports, and helping manage care.89 CHW interventions have been found to reduce costs and improve outcomes for vulnerable populations,90 an appealing solution for rural providers facing financial challenges. Additionally, CHWs who are members of the rural communities they serve may engender greater trust and engage hard-to-reach rural populations.

CONCLUSION

As we envision new frontiers in rural public health, it is critical to consider the enduring health disparities faced by rural residents. Although rural public health innovations from a century ago may appear to hold promise today, we must acknowledge that individual programs and policies will be insufficient to yield the needed results. Achieving rural health equity also requires focused and sustained resource investment in rural people and institutions, particularly in BIPOC communities. Some of these critical investments, such as shifting from a health financing model based on cure to one based on prevention, are part of a broader public health imperative but also have unique rural implications. For example, federal and state rural health initiatives have emphasized the construction of hospitals, increasing availability of health care providers, and expanding health insurance coverage.91 Although health care access is essential, these investments address a single determinant of health while rendering rural communities economically dependent on the health care sector. Within the meager financial resources available for prevention and public health, there is evidence of funding policies that favor larger urban departments of public health through what some have called “structural urbanism.”92 Multiple studies have revealed that, perversely, well-resourced health departments are best able to garner additional resources, whereas those with the greatest needs fail to obtain sufficient funding.93

Beyond funding for health and health care services, the new frontier of rural public health must emphasize rural improvements in the social determinants of health. Research suggests that rural poverty is a primary driver of the growing rural mortality penalty, particularly for poor Black rural residents who experience death rates up to three times those of affluent urban residents.94 As we enter economic decline from COVID-19, we know that many rural communities are already economically fragile and will experience less resilience to this global shock. Federal and state governments must commit to a Marshall Plan for the rural United States, focused on revitalizing Main Street, developing public health infrastructure, and implementing and evaluating rural-specific population health initiatives. Finally, we must consider the wisdom of early rural public health experts and ensure that rural communities are meaningfully engaged in all aspects of their economic and health improvement.

ENDNOTES

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Stiles C. W. The Rural Health Movement. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1911;(2):123. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia M. C., Faul M., Massetti G. et al. Reducing Potentially Excess Deaths From the Five Leading Causes of Death in the Rural United States. MMWR: Surveillance Summaries. 2017;(2):1–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6602a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman A. W., Lumsden L. L. Typhoid Fever in Rural Virginia a Preliminary Report. American Journal of Public Health. 1912;(4):243. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2.4.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. “Should Rural Schools Be Closed?” American Journal of Public Health 4, no. 5 (1914): 436–437; J. P. Bragdon, W. W. Cuzner, and W. T. Councilman, “Report on the Health of York, Maine,” American Journal of Public Health 5, no. 3 (1915): 248–249; A.G. Fort, “The Negro Health Problem in Rural Communities,” American Journal of Public Health 5, no. 3 (1915): 191–193; A. W. Freeman, “The Prevention of Typhoid Fever in the Rural Districts of Virginia,” American Journal of Public Health 3, no. 12 (1913): 1322–1325; Freeman and Lumsden, “Typhoid Fever in Rural Virginia,” 240–252; P. E. Garrison, J. F. Siler, and W. J. Macneal, “A Study of Methods of Sewage Disposal in Industrial and Rural Communities and Suggestions for Their Improvement,” American Journal of Public Health 5, no. 9 (1915): 820–832; S. A. Knopf, “The Modern Aspect of the Tuberculosis Problem in Rural Communities and the Duty of the Health Officers,” American Journal of Public Health 4, no. 12 (1914): 1127–1135; W. S. Rankin, “Rural Sanitation: Definition, Field, Principles, Methods, and Costs,” American Journal of Public Health 6, no. 6 (1916): 554–558; R. M. Simpson, “Rural Typhoid in Manitoba,” American Journal of Public Health 3, no. 8 (1913): 734–736; E. G. Williams, “The Rural Sewage Problem,” American Journal of Public Health 6, no. 11 (1916): 1184–1186.

- 5. “Front Matter,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 37, no. 2 (1911): i–221.

- 6.Shattuck L. Report of the Sanitary Commission of Massachusetts, 1850. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1850. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crum F. S. A Statistical Study of Diphtheria. American Journal of Public Health. 1917;(5):445–477. doi: 10.2105/ajph.7.5.445-a. Freeman and Lumsden, “Typhoid Fever in Rural Virginia,” 240–252; Knopf, “Modern Aspect of Tuberculosis,” 1127–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone B. H. Drinking Water in Relation to Typhoid Fever in Rural Communities. Public Health Papers and Reports. 1906:177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. D. Cole, “Control of Infectious Diseases,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 48, no. 29 (1999): 621–629; R. N. Anderson, “Deaths: Leading Causes for 1999,” National Vital Statistics Reports 49, no. 11 (2001): 1–87.

- 10.Conrad C., Bradley H. M., Broz D. et al. “Community Outbreak of HIV Infection Linked to Injection Drug Use of Oxymorphone—Indiana, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2015;(16):443–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. M. E. Evans, S. M. Labuda, V. Hogan, et al., “Notes From the Field: HIV Infection Investigation in a Rural Area—West Virginia, 2017,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67, no. 8 (2018): 257–258; J. R. Havens, M. R. Lofwall, S. D. W. Frost, et al., “Individual and Network Factors Associated With Prevalent Hepatitis C Infection Among Rural Appalachian Injection Drug Users,” American Journal of Public Health 103, no. 1 (2013): e44–e52.

- 12.Van Handel M. M., Rose C. E., Hallisey E. J. et al. County-Level Vulnerability Assessment for Rapid Dissemination of HIV or HCV Infections Among Persons Who Inject Drugs, United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2016;(3):323–331. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziller E. C., Lenardson J. D., Paluso N. Preventive Health Service Use Among Rural Women. Portland, ME: Maine Rural Health Research Center; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser Family Foundation. COVID-19 in Metropolitan and Non-Metropolitan Counties,” May 21, 2020, https://www.kff.org/slideshow/covid-19-in-metropolitan-and-non-metropolitan-counties (accessed August 3, 2020)

- 15.Hoyert D. L. Maternal Mortality and Related Concepts. Vital Health Statistics. 2007;(33):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh G. K., Yu S. M. “Infant Mortality in the United States, 1915–2017: Large Social Inequalities Have Persisted for Over a Century. International Journal of Maternal and Child Health and AIDS. 2019;(1):19–31. doi: 10.21106/ijma.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frankel L. K. The Present Status of Maternal and Infant Hygiene in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1927;(12):1209–1217. doi: 10.2105/ajph.17.12.1209-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neff J. S. Recent Public Health Work in the United States Especially in Relation to Infant Mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 1915;(10):965–981. doi: 10.2105/ajph.5.10.965-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrd D. W. Maternity and Infant Mortality. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1917;(4):177–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirshberg A., Srinivas S. K. Epidemiology of Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Seminars in Perinatology. 2017;(6):332–337. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozhimannil K. B., Interrante J. D., Henning-Smith C., Admon L. K. Rural–Urban Differences in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the US, 2007–15. Health Affairs. 2019;(12):2077–2085. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ely D. M., Hoyert D. L. Differences Between Rural and Urban Areas in Mortality Rates for the Leading Causes of Infant Death: United States, 2013–2015. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;(300):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung P., Henning-Smith C. E., Casey M. M., Kozhimannil K. B. “Access to Obstetric Services in Rural Counties Still Declining, With 9 Percent Losing Services, 2004–14. Health Affairs. 2017;(9):1663–1671. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung P., Casey M. M., Kozhimannil K. B., Karaca-Mandic P., Moscovice I. S. “Rural–Urban Differences in Access to Hospital Obstetric and Neonatal Care: How Far Is the Closest One? Journal of Perinatology. 2018;(6):645–652. doi: 10.1038/s41372-018-0063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ibid.

- 27.Mustard H. S., Mountin J. W. Measurements of Efficiency and Adequacy of Rural Health Service. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health. 1929;(8):887–892. doi: 10.2105/ajph.19.8.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mountin J. W., Pennell E. H., Georgie S. B. Location and Movement of Physicians, 1923 and 1938: Changes in Urban and Rural Totals for Established Physicians. Public Health Reports. 1945;(7):173–185. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziller E. C. Access to Medical Care in Rural America. In: Warren J. C., Smiley K. B., editors. Rural Public Health: Best Practices and Preventive Models. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2014. pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- 30. North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, “162 Rural Hospital Closures: January 2005–Present,” Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures (accessed May 27, 2020)

- 31. Authors’ calculations of data from: Health Resources & Services Administration, Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) Data, 2019, distributed by Rural Health Information Hub, “Rural Data Explorer,” https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/data-explorer?id=210 (accessed June 17, 2020)

- 32.Murphy J. A. Health Problems of the Indians. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1911;(2):103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trask J. W. The Significance of the Mortality Rates of the Colored Population of the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1916;(3):254–259. doi: 10.2105/ajph.6.3.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fort, “Negro Health Problem in Rural Communities,” 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Knox J. H. Reduction of Maternal and Infant Mortality in Rural Areas. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health. 1935;(1):68–75. doi: 10.2105/ajph.25.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.James C. V., Moonesinghe R., Wilson-Frederick S. M. et al. “Racial/Ethnic Health Disparities Among Rural Adults—United States, 2012–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries. 2017;(23):1–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6623a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kozhimannil K. B., Henning-Smith C. Racism and Health in Rural America. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2018;(1):35–43. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharp G., Lee B. A. New Faces in Rural Places: Patterns and Sources of Nonmetropolitan Ethnoracial Diversity Since 1990. Rural Sociology. 2017;(3):411–443. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kozhimannil and Henning-Smith, “Racism and Health in Rural America,” 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Henning-Smith C. E., Hernandez A. M., Hardeman R. R., Ramirez M. R., Kozhimannil K. B. Rural Counties With Majority Black or Indigenous Populations Suffer the Highest Rates of Premature Death in the US. Health Affairs. 2019;(12):2019–2026. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodgetts C. A. Management of Diphtheria Epidemics in Rural Districts. Public Health Papers and Reports. 1894:89–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Knopf, “Modern Aspect of Tuberculosis,” 1128.

- 43.Ruediger G. F. A Program of Public Health for Towns, Villages and Rural Communities. American Journal of Public Health. 1917;(3):235–239. doi: 10.2105/ajph.7.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Crum, “Study of Diphtheria,” 445–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Young C. C., Crooks M. “Comparative Studies of Diphtheria Cultures of Loeffler’s Medium With the Original Swabs Transported by Mail. American Journal of Public Health. 1921;(3):241–244. doi: 10.2105/ajph.11.3.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meit M., Ettaro L., Hamlin B. N., Piya B. Rural Public Health Financing: Implications for Community Health Promotion Initiatives. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2009;(3):210–215. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000349738.73619.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beatty K. E., Erwin P. C., Brownson R. C., Meit M., Fey J. Public Health Agency Accreditation Among Rural Local Health Departments: Influencers and Barriers. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2018;(1):49–56. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKillop M., Ilakkuvan V. The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2019. Washington, DC: Trust for America’s Health; 2019. Meit et al., “Rural Public Health Financing,” 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris J. K., Beatty K., Leider J. P., Knudson A., Anderson B. L., Meit M. The Double Disparity Facing Rural Local Health Departments. Annual Review of Public Health. 2016;(1):167–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sedgwick W. T., Taylor G. R., MacNutt J. S. “Is Typhoid Fever a ‘Rural’ Disease? The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1912;(2):141–192. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Knox, “Maternal and Infant Mortality,” 68–75; D. G. Wiehl, “The Correction of Infant Mortality Rates for Residence,” American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health 19, no. 5 (1929): 495–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52. Murphy, “Health Problems of the Indians,” 103–109; Trask, “Mortality Rates of the Colored Population,” 254–259.

- 53.Bennett K. J., Borders T. F., Holmes G. M., Kozhimannil K. B., Ziller E. What Is Rural? Challenges and Implications of Definitions That Inadequately Encompass Rural People and Places. Health Affairs. 2019;(12):1985–1992. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Preble P. Public Health Administration: With Special Reference to Towns and Rural Communities. Public Health Reports. 1917;(9):346–351. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Knopf, “Modern Aspect of Tuberculosis,” 1128.

- 56.Talbot J. A., Elbaum Williamson M., Pearson K. Advancing Tobacco Prevention and Control in Rural America. Portland, ME: Maine Public Health Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ziller et al., Preventive Health Service Use.

- 58.Benitez J. A., Seiber E. E. “US Health Care Reform and Rural America: Results From the ACA’s Medicaid Expansions. Journal of Rural Health. 2018;(2):213–222. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ziller E., Lenardson J., Coburn A. Rural Implications of Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act. Minneapolis, MN: State Health Access Data Assistance Center; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fort, “Negro Health Problem in Rural Communities,” 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61. Knox, “Maternal and Infant Mortality,” 73.

- 62. E. Patten, “The Black–White and Urban–Rural Divides in Perceptions of Racial Fairness,” Pew Research Center, August 28, 2013, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/08/28/the-black-white-and-urban-rural-divides-in-perceptions-of-racial-fairness (accessed August 3, 2020)

- 63.Ruediger G. F. A Program of Public Health for Towns, Villages and Rural Communities. American Journal of Public Health. 1917;(3):235–239. doi: 10.2105/ajph.7.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Draper W. F. Rural Health Work From the National Viewpoint. American Journal of Public Health. 1923;(7):547–549. doi: 10.2105/ajph.13.7.547. Ruediger, “Public Health for Towns,” 235–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller K. E., Goddard C. W., Smith C. E. et al. Report of the Committee on Rural Health Administration. American Journal of Public Health. 1922;(4):317. doi: 10.2105/ajph.12.4.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Humphries D. L., Hyde J., Hahn E. et al. Cross-Jurisdictional Resource Sharing in Local Health Departments: Implications for Services, Quality, and Cost. Frontiers in Public Health. 2018:115. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Center for Sharing Public Health Services, “Rural/Small Jurisdictions,” https://phsharing.org/issues/rural-small-jurisdictions (accessed May 27, 2020)

- 68.Cattaraugus County Department of Public Health. as quoted in Randall, “The Public Health Nurse in a Rural Health Department: An Introductory Report on the Study in Progress in Cattaraugus County. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health. 1931;(7):737–738. doi: 10.2105/ajph.21.7.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Randall M. G. How Much Work Can a Rural Public Health Nurse Do? Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1936;(2):163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lewenson S. B. Town and Country Nursing: Community Participation and Nurse Recruitment. In: Kirchgessner J. C., Keeling A. W., editors. Nursing Rural America: Perspectives From the Early 20th Century. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2014. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cockerham A. Z. Mary Breckinridge and the Frontier Nursing Service: Saddlebags and Swinging Bridges. In: Kirchgessner J. C., Keeling A. W., editors. Nursing Rural America: Perspectives From the Early 20th Century. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2014. pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- 72. 2016 National Profile of Local Health Departments (Washington, DC: National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2017); A. Knudsen and M. Meit, Public Health Nursing: Strengthening the Core of Rural Public Health (Leawood, KS: National Rural Health Association, 2011).

- 73. Minnesota Department of Health, “Minnesota Rural Public Health Nurse Loan Forgiveness Guidelines,” updated February 12, 2020, https://www.health.state.mn.us/facilities/ruralhealth/funding/loans/publichealth.html#Example1 (accessed August 3, 2020)

- 74. National Area Health Education Center (AHEC) Organization, https://www.nationalahec.org (accessed May 27, 2020)

- 75.Whittaker J., Kellom K., Matone M., Cronholm P. “A Community Capitals Framework for Identifying Rural Adaptation in Maternal–Child Home Visiting. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2019 doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001042. Epub ahead of print July 3, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thoms A. B., Pathfinders . A History of the Progress of Colored Graduate Nurses. New York, NY: Kay Printing House; 1929. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Betancourt J. R., Green A. R., Carrillo J. E., Ananeh-Firempong O., 2nd Defining Cultural Competence: A Practical Framework for Addressing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health and Health Care. Public Health Reports. 2003;(4):293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goodman M. S., Plepys C. M., Bather J. R., Kelliher R. M., Healton C. G. Racial/Ethnic Diversity in Academic Public Health: 20-Year Update. Public Health Reports. 2019;(1):74–81. doi: 10.1177/0033354919887747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Greenleaf C. A. School Health Work in a Rural County. Journal of Educational Sociology. 1929;(1):44–59. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Byrd, “Infant Mortality,” 177–180; W. H. Pickett, “The Rural Health Commissioner,” American Journal of Public Health (New York, NY : 1912) 14, no. 6 (1924): 510–512; T. Parran, “Cooperative County Health Work,” Public Health Reports 40, no. 20 (1925): 983–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child,” reviewed February 10, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/wscc/index.htm (accessed August 3, 2020)

- 82.Crouch E., Radcliff E., Probst J. C. et al. “Rural–Urban Differences in Adverse Childhood Experiences Across a National Sample of Children. Journal of Rural Health. 2020;(1) doi: 10.1111/jrh.12366. 55–64; K. J. Foli, S. Woodcox, S. Kersey, et al., “Trauma-Informed Parenting Classes Delivered to Rural Kinship Parents: A Pilot Study,” Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 24, no. 1 (2018): 62–75; S. Shamblin, D. Graham, and J. A. Bianco, “Creating Trauma-Informed Schools for Rural Appalachia: The Partnerships Program for Enhancing Resiliency, Confidence and Workforce Development in Early Childhood Education,” School Mental Health 8, no. 1 (2016): 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Plunkett R., Leipert B., Olson J. K. et al. Understanding Women’s Health Promotion and the Rural Church. Qualitative Health Research. 2014;(12):1721–1731. doi: 10.1177/1049732314549025. M. Bencivenga, S. DeRubis, P. Leach, et al., “Community Partnerships, Food Pantries, and an Evidence-Based Intervention to Increase Mammography Among Rural women,” Journal of Rural Health 24, no. 1 (2008): 91–95; M. G. Flaherty and D. Miller, “Rural Public Libraries as Community Change Agents: Opportunities for Health Promotion,” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 57, no. 2 (2016): 143–150; M. Margaret, C. Angela, N. Christy, et al., “Extension as a Backbone Support Organization for Physical Activity Promotion: A Collective Impact Case Study From Rural Kentucky,” Journal of Physical Activity and Health 17, no. 1 (2020): 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Havey I. M. What Preparation Should the Public Health Nurse Have for Rural Work? American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health. 1930;(7):734. doi: 10.2105/ajph.20.7.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Knox, “Maternal and Infant Mortality,” 71.

- 86.Rood E. Participation of Lay People in the Promotion of a Rural Child Health Program. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health. 1932;(10):1028. doi: 10.2105/ajph.22.10.1027-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ibid, 1027–1032.

- 88. American Public Health Association, “Community Health Workers,” 2020, https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers (accessed August 3, 2020)

- 89.Kim K., Choi J. S., Choi E. et al. Effects of Community-Based Health Worker Interventions to Improve Chronic Disease Management and Care Among Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;(4):e3–e28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moffett M. L., Kaufman A., Bazemore A. Community Health Workers Bring Cost Savings to Patient-Centered Medical Homes. Journal of Community Health. 2018;(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0403-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Probst J., Eberth J. M., Crouch E. Structural Urbanism Contributes to Poorer Health Outcomes for Rural America. Health Affairs. 2019;(12):1976–1984. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ibid.

- 93. Committee on Public Health Strategies to Improve Health, Institute of Medicine, “Reforming Public Health and Its Financing,” in For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2012). [PubMed]

- 94.Singh G. K., Siahpush M. “Widening Rural–Urban Disparities in All-Cause Mortality and Mortality From Major Causes of Death in the USA, 1969–2009. Journal of Urban Health. 2014;(2):272–292. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9847-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]