Key Points

Question

Is Lyme neuroborreliosis associated with the development of psychiatric disease?

Findings

In this cohort study of 2897 patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis in Denmark, Lyme neuroborreliosis was not associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disease or psychiatric hospital contact. Lyme neuroborreliosis was associated with increased receipt of anxiolytic, hypnotic and sedative, and antidepressant medications within the first year after diagnosis but not thereafter.

Meanings

The study’s results indicated that patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis did not have an increased risk of developing psychiatric disease overall, and the observed increase in the short-term receipt of some psychiatric medications may have been associated with the use of these medications for pain management.

Abstract

Importance

The association of Lyme neuroborreliosis with the development of psychiatric disease is unknown and remains a subject of debate.

Objective

To investigate the risk of psychiatric disease, the percentage of psychiatric hospital inpatient and outpatient contacts, and the receipt of prescribed psychiatric medications among patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis compared with individuals in a matched comparison cohort.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nationwide population-based matched cohort study included all residents of Denmark who received a positive result on an intrathecal antibody index test for Borrelia burgdorferi (patient cohort) between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2015. Patients were matched by age and sex to a comparison cohort of individuals without Lyme neuroborreliosis from the general population of Denmark. Data were analyzed from February 2019 to March 2020.

Exposures

Diagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis, defined as a positive result on an intrathecal antibody index test for B burgdorferi.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The 0- to 15-year hazard ratios for the assignment of psychiatric diagnostic codes, the difference in the percentage of psychiatric inpatient and outpatient hospital contacts, and the difference in the percentage of prescribed psychiatric medications received among the patient cohort vs the comparison cohort.

Results

Among 2897 patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis (1646 men [56.8%]) and 28 970 individuals in the matched comparison cohort (16 460 men [56.8%]), the median age was 45.7 years (interquartile range [IQR], 11.5-62.0 years) for both groups. The risk of a psychiatric disease diagnosis and the percentage of hospital contacts for psychiatric disease were not higher among patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis compared with individuals in the comparison cohort. A higher percentage of patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis compared with individuals in the comparison cohort received anxiolytic (7.2% vs 4.7%; difference, 2.6%; 95% CI, 1.6%-3.5%), hypnotic and sedative (11.0% vs 5.3%; difference, 5.7%; 95% CI, 4.5%-6.8%), and antidepressant (11.4% vs 6.0%; difference, 5.4%; 95% CI, 4.3%-6.6%) medications within the first year after diagnosis, after which the receipt of psychiatric medication returned to the same level as the comparison cohort.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this population-based matched cohort study, patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis did not have an increased risk of developing psychiatric diseases that required hospital care or treatment with prescription medication. The increased receipt of psychiatric medication among patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis within the first year after diagnosis, but not thereafter, suggests that most symptoms associated with the diagnosis subside within a short period.

This cohort study uses data from Danish national registries to examine the risk of psychiatric disease, the percentage of psychiatric hospital inpatient and outpatient contacts, and the receipt of prescribed psychiatric medications among patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis in Denmark.

Introduction

The spectrum of residual symptoms after diagnosis with Lyme neuroborreliosis, a tickborne infection caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex, remains a subject of debate.1 A previous study reported that Danish patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis did not experience increases in long-term mortality and somatic disease burden or a decrease in socioeconomic status compared with the general population of Denmark.2,3

Lyme neuroborreliosis has been associated with a variety of psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, mood affective disorders, suicide, and anxiety.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 However, most studies of these associations have been limited by flaws in study design. To our knowledge, no nationwide population-based cohort study with long-term follow-up of the potential association between Lyme neuroborreliosis and the risk of developing psychiatric diseases has been performed. We enrolled a cohort of Danish patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis, which consisted of all residents of Denmark who had a positive result on the B burgdorferi intrathecal antibody index test for the first time between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2015, to examine the risk of psychiatric diagnosis and hospital admission for psychiatric disease as well as the receipt of prescribed psychiatric medications compared with a matched comparison cohort of individuals without Lyme neuroborreliosis from the general population in Denmark.

Methods

This nationwide population-based matched cohort study has been described previously.2,3,12,13 The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and the National Board of Health with a waiver of informed consent because the study was based on public data obtained from Danish national registries and deidentified patient medical records; thus, informed consent was not required by Danish law. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

During the study period (1995-2015), Denmark had a population of 5.2 million to 5.7 million individuals, and tax-supported health care was provided at no cost to all Danish residents.14,15

We used the unique 10-digit identification number assigned to all Danish residents at birth or immigration to identify individuals in the Danish Registries.15,16,17,18,19,20,21 We obtained results from B burgdorferi intrathecal antibody index tests from all Danish departments of microbiology between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2015. Data on dates of birth, sex, immigration, emigration, vital status, and dates of death were extracted from the Danish Civil Registration System.16 Data on psychiatric diseases, which were based on diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), and data on psychiatric inpatient and outpatient hospital contacts were extracted from the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register.17 Data on types and dosages of prescribed medications as well as dates of medication receipt were collected from the Danish National Prescription Registry.18,19 Additional data on comorbidities were obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish Cancer Registry.20,21 Loss to follow-up in the Danish registries is rare and has been estimated at approximately 0.005%.2

Study Population

We included all Danish residents who received a positive result on the B burgdorferi intrathecal antibody index test (patient cohort) for the first time between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2015, with the date of study inclusion defined as the first date of a positive result on the test.

From the Danish Civil Registration System, we extracted 10 individuals from the general population for each patient with Lyme neuroborreliosis; these individuals were matched based on age and sex to form the comparison cohort. All individuals in the comparison cohort did not have positive results on the B burgdorferi intrathecal antibody index test, and they were assigned the same date of study inclusion as the corresponding patient with Lyme neuroborreliosis.

We compared patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis with individuals in the comparison cohort to examine the risk of a psychiatric diagnosis overall and stratified by subcategories. We calculated the time from the date of study inclusion until death, emigration, loss to follow-up, event of interest, 15 years after study inclusion, or March 1, 2016, whichever occurred first. As a measure of risk, we compared patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis with individuals in the comparison cohort to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% CIs of psychiatric diagnoses using stratified Cox regression analyses. For each analysis of psychiatric diseases overall and by subgroup, we excluded all participants in the patient and comparison cohorts who had been diagnosed with the given psychiatric disease of interest before study inclusion.

Hospital Contacts and Medication Receipt

We identified all inpatient and outpatient psychiatric hospital contacts between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2015, that included a primary or secondary diagnosis of a psychiatric disease based on ICD-10-CM codes. For participants in both the patient and comparison cohorts, we calculated the percentage of individuals who had a psychiatric hospital contact with a diagnosis of a psychiatric disease (overall and by subcategory) each year, beginning 10 years before study inclusion until death, emigration, loss to follow-up, event of interest, 15 years after study inclusion, or March 1, 2016, whichever occurred first. This calculation was performed by dividing the number of participants with a hospital contact by the total number of participants in each cohort for a given year. The percentage of patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis who had hospital contacts was subtracted from the percentage of individuals in the comparison cohort who had hospital contacts to calculate percentage difference and corresponding 95% CIs, as described previously.22 No adjustments for covariates were made in these analyses.

We extracted data on all receipt of psychiatric drugs from Danish pharmacies according to the second and third levels of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification.23 We examined the receipt of prescribed medications as a dichotomic variable (receipt vs no receipt of any medication dose) of psycholeptic medications (ATC code N05, subdivided into antipsychotic [ATC code N05A], anxiolytic [ATC code N05B], and hypnotic and sedative [ATC code N05C] medications) and psychoanaleptic medications (ATC code N06, including the subcategory of antidepressant medications [ATC code N06A], subdivided into nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitor [ATC code N06AA], selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [ATC code N06AB], nonselective monoamine oxidase inhibitor [ATC code N06AC], monoamine oxidase A inhibitor [ATC code N06AD], and other antidepressant [ATC code N06AE] medications). We calculated the percentage of participants in both the patient and comparison cohorts who received prescribed psychiatric medications each year, beginning 10 years before study inclusion until 15 years after study inclusion, death, emigration, loss to follow-up, or March 1, 2016, whichever occurred first. We subtracted the percentage of patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis who received psychiatric medications from the percentage of individuals in the comparison cohort who received psychiatric medications to calculate percentage differences and corresponding 95% CIs, as described previously.22 No adjustments for covariates were made in these analyses.

We were not able to differentiate the period before the receipt of antibiotic medications from the period after the receipt of antibiotic medications. However, given the fact that Danish national guidelines, with which physicians generally comply, specify that antibiotic treatment is indicated for patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis, we assumed that almost all follow-up time represented the period after the receipt of antibiotic medications.

Statistical Analysis

At study inclusion, we estimated the median age (with interquartile range [IQR]), the percentage of male individuals, the percentage of individuals born in Denmark, and the percentage of individuals with a Charlson comorbidity index score higher than 1 for participants in the patient and comparison cohorts.24 To investigate different aspects of psychiatric disorders, we used 3 different outcomes: risk of psychiatric disease, percentage of psychiatric hospital contacts, and percentage of prescribed psychiatric medications received.

We investigated the risk of developing psychiatric disease overall (ICD-10-CM codes F00-F99) and the risk of developing the most common subcategories of psychiatric disease, which included mental and behavioral disorders owing to psychoactive substance use (ICD-10-CM codes F10-F19), schizophrenia (ICD-10-CM code F20), mood affective disorders (ICD-10-CM codes F30-F39), anxiety (ICD-10-CM code F41), obsessive-compulsive disorders (ICD-10-CM code F42), and reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders (ICD-10-CM code F43).

To adjust for country of origin, a sensitivity analysis was performed, in which all participants in the patient and comparison cohorts who were not born in Denmark were excluded. All individuals in the comparison cohort who were matched to excluded patients were also excluded.

We used SPSS Statistics, version 25 (SPSS), and R software, version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), for all analyses. Data were analyzed from February 2019 to March 2020.

Results

At study inclusion, participants in the patient and comparison cohorts did not differ with regard to age, sex, or Charlson comorbidity index score. Of the 2897 patients who had positive results on the B burgdorferi intrathecal antibody index test, the median age was 45.7 years (IQR, 11.5-62.0 years), and 1646 patients (56.8%) were male, with 457 patients (15.8%) having a comorbidity score greater than 1. Of the 28 970 individuals in the comparison cohort, the median age was identical to that of the patient cohort, and 16 460 individuals (56.8%) were male, with 4994 individuals (17.2%) having a comorbidity score greater than 1 (Table 1). A larger percentage of patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis (2799 patients [96.6%]) were born in Denmark compared with individuals in the comparison cohort (27 055 individuals [93.4%]). No differences were observed in the percentage of psychiatric diseases among participants in the patient and comparison cohorts before study inclusion.

Table 1. Cohort Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient cohort | Comparison cohort | |

| Participants, No. | 2897 | 28 970 |

| Age at study inclusion, median (IQR), y | 45.7 (11.5-62.0) | 45.7 (11.5-62.0) |

| Male sex | 1646 (56.8) | 16 460 (56.8) |

| Born in Denmark | 2799 (96.6) | 27 055 (93.4) |

| Charlson comorbidity index score >0 | 457 (15.8) | 4994 (17.2) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis at study inclusion | ||

| All psychiatric diseasesa | 112 (3.9) | 1223 (4.2) |

| Mental and behavioral disorder owing to psychoactive substance useb | 24 (0.8) | 280 (1.0) |

| Schizophreniac | 16 (0.6) | 104 (0.4) |

| Mood affective disorderd | 53 (1.8) | 384 (1.3) |

| Anxietye | 19 (0.7) | 105 (0.4) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorderf | 12 (0.4) | 12 (0.04) |

| Reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorderg | 30 (1.0) | 308 (1.1) |

Abbreviations: ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification; IQR, interquartile range.

Includes ICD-10-CM codes F00-F99.

Includes ICD-10-CM codes F10 to F19.

Includes ICD-10-CM code F20.

Includes ICD-10-CM codes F30 to F39.

Includes ICD-10-CM code F41.

Includes ICD-10-CM code F42.

Includes ICD-10-CM code F43.

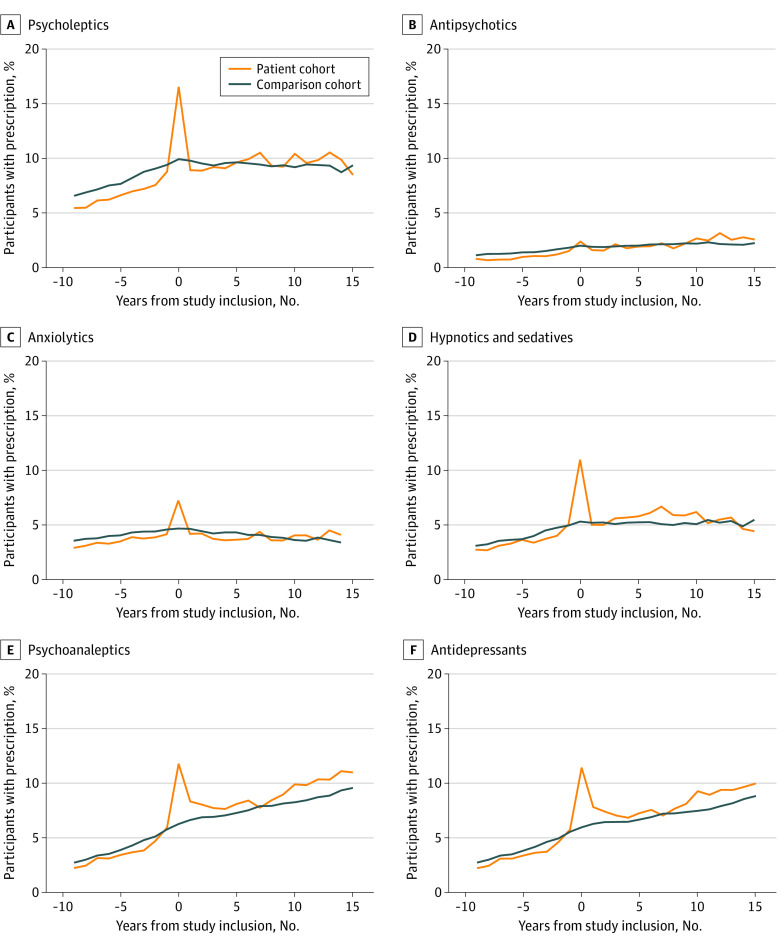

No increase in the overall risk of developing psychiatric disease (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 09-1.2) or any subcategory of psychiatric disease (for mental and behavioral disorders owing to psychoactive substance use, HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.6-1.5; for schizophrenia, HR, 0.8; 95% CI, 04-2.0; for mood affective disorders, HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9-1.6; for anxiety, HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.0-2.2; for obsessive-compulsive disorders, HR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.2-1.6; and for reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders, HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.8-1.5) was found in patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis compared with individuals in the comparison cohort (Table 2; Figure 1). The results for the risk of developing psychiatric diseases did not change when we performed a sensitivity analysis in which all participants who were not born in Denmark were excluded.

Table 2. Hazard Ratios of Psychiatric Diseases in Patients With Lyme Neuroborreliosis Compared With the Comparison Cohort.

| Diagnosis | Individuals at risk, No. | Events, No. | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient cohort | Comparison cohort | Patient cohort | Comparison cohort | ||

| All psychiatric diseasesa | 2785 | 27 747 | 165 | 1559 | 1.1 (0.9-1.2) |

| Mental and behavioral disorder owing to psychoactive substance useb | 2873 | 28 690 | 24 | 247 | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) |

| Schizophreniac | 2881 | 28 866 | 6 | 73 | 0.8 (0.4-2.0) |

| Mood affective disorderd | 2785 | 27 747 | 57 | 464 | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

| Anxietye | 2878 | 28 865 | 25 | 175 | 1.5 (1.0-2.2)f |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorderg | 2885 | 28 958 | 4 | 69 | 0.6 (0.2-1.6) |

| Reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorderh | 2867 | 28 662 | 56 | 508 | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Includes ICD-10-CM codes F00-F99.

Includes ICD-10-CM codes F10 to F19.

Includes ICD-10-CM code F20.

Includes ICD-10-CM codes F30 to F39.

Includes ICD-10-CM code F41.

Actual value of lower 95% CI was 0.956.

Includes ICD-10-CM code F42.

Includes ICD-10-CM code F43.

Figure 1. Cumulative Risk of Psychiatric Diseases After Study Inclusion.

A, Includes ICD-10-CM codes F00-F99. B, Includes ICD-10-CM codes F10-F19. C, Includes ICD-10-CM code F20. D, Includes ICD-10-CM codes F30-F39. E, Includes ICD-10-CM code F41. F. Includes ICD-10-CM code F42. G, Includes ICD-10-CM code F43. ICD-10-CM indicates International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification.

We also calculated the proportion of each cohort with hospital contact in the period from 10 years before to 15 years after study inclusion by subcategory of psychiatric disease and calculated the difference and corresponding 95% CIs (Figure 2). The proportion of individuals with hospital contact in the patient cohort compared with the comparison cohort was 10.9% vs 10.2% (difference, 0.7%; 95% CI, −0.5% to 1.9%) for all psychiatric diseases, 1.0% vs 1.1% (difference, −0.1%; 95% CI, −0.5% to 0.3%) for mental and behavioral disorders owing to psychoactive substance use, 0.5% vs 0.6% (difference, −0.1%; 95% CI, −0.3% to 1.4%) for schizophrenia, 3.0% vs 2.1% (difference, 0.9%; 95% CI, 0%-1.6%) for mood affective disorders, 1.1% vs 0.8% (difference, 0.3%; 95% CI, 0%-0.7%) for anxiety, 0.3% vs 0.3% (difference, 0%; 95% CI, −0.2% to 0.2%) for obsessive-compulsive disorder, and 2.2% vs 2.0% (difference, 0.2%; 95% CI, −0.3% to 0.8%) for reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders. The results for psychiatric hospital contacts did not change when we performed a sensitivity analysis in which all participants who were not born in Denmark were excluded.

Figure 2. Participants With Psychiatric Hospital Contact.

A, Includes ICD-10-CM codes F00-F99. B, Includes ICD-10-CM codes F10-F19. C, Includes ICD-10-CM code F20. D, Includes ICD-10-CM codes F30-F39. E, Includes ICD-10-CM code F41. F. Includes ICD-10-CM code F42. G, Includes ICD-10-CM code F43. ICD-10-CM indicates International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification.

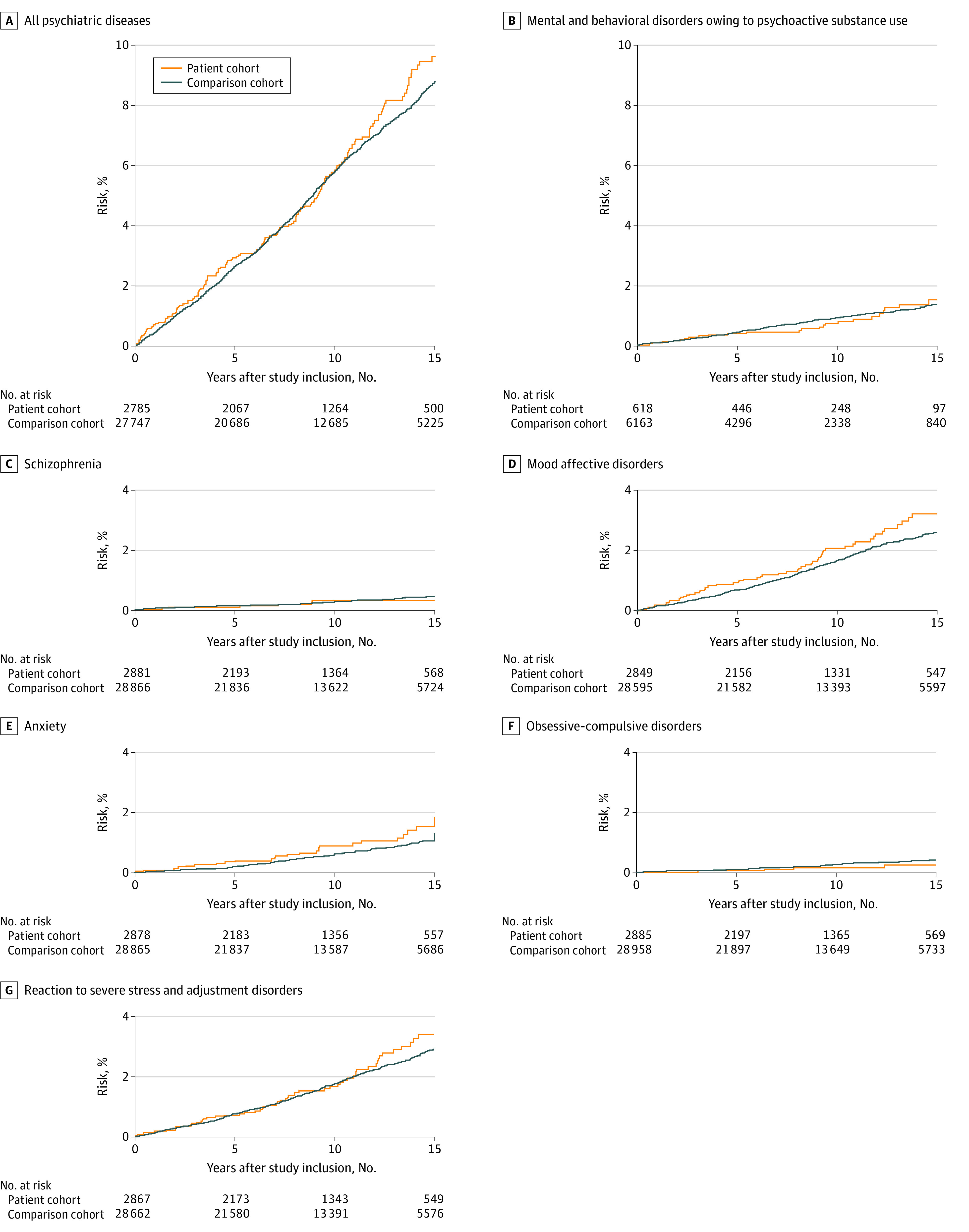

Within the first year after study inclusion, more patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis than individuals in the comparison cohort received prescriptions for psycholeptic (16.5% vs 9.9%, respectively; difference, 6.6%; 95% CI, 5.2%-8.0%), anxiolytic (7.2% vs 4.7%; difference, 2.6%; 95% CI, 1.6%-3.5%), hypnotic and sedative (11.0% vs 5.3%; difference, 5.7%; 95% CI, 4.5%-6.8%), psychoanaleptic (11.8% vs 6.3%; difference, 5.5%; 95% CI, 4.3%-6.7%), antidepressant (11.4% vs 6.0%; difference, 5.4%; 95% CI, 4.3%-6.6%), nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitor (5.4% vs 1.0%; difference, 4.4%; 95% CI, 3.6%-5.2%), and other antidepressant (2.8% vs 1.8%; difference, 1.0%; 95% CI, 0.4%-1.6%) medications (Figure 3; eTable and eFigure in the Supplement). We observed no substantial difference in the receipt of prescriptions for any of these medications after this period (ie, >1 year after study inclusion). There were no differences between the patient and comparison cohorts for the receipt of antipsychotic (2.4% vs 2.0%, respectively; difference, 0.4%; 95% CI, −0.2% to 0.9%), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (4.6% vs 3.9%; difference, 0.7%; 95% CI, −0.1% to 1.5%), nonselective monoamine oxidase inhibitor (0% vs 0%), or monoamine oxidase A inhibitor (0% vs 0%) medications within the first year after study inclusion (Figure 3; eTable and eFigure in the Supplement). The results for the receipt of prescribed psychiatric medications did not change when we performed a sensitivity analysis in which all participants who were not born in Denmark were excluded.

Figure 3. Participants With Any Prescription for Psychiatric Medication per Year.

A, Includes ATC code N05. B, Includes ATC code N05A. C, Includes ATC code N05B. D, Includes ATC code N05C. E, Includes ATC code N06. F, Includes ATC code N06A. ATC indicates Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification.

Discussion

In this nationwide population-based matched cohort study of patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis, we observed no increased risk of psychiatric diseases among patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis compared with individuals in a comparison cohort who were matched by age and sex. Furthermore, the frequency of hospital contacts for psychiatric diseases was not higher among the patient cohort compared with the comparison cohort. The receipt of anxiolytic, hypnotic and sedative, and antidepressant medications was higher among patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis within the first year after study inclusion but not thereafter.

Comparison With Other Studies

In our study, we used 3 different measures of psychiatric disease: the risk of being diagnosed with psychiatric disease, the percentage of individuals with hospital contacts for psychiatric diseases, and the percentage of prescribed psychiatric medications received. The fact that patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis received more psychiatric medications within the first year after study inclusion but not thereafter, and no concurrent increased risk of psychiatric disease or increased hospital contact owing to psychiatric disease was observed within the same period suggests that the consequences of Lyme neuroborreliosis with regard to psychiatric disease might be temporary for most patients. This interpretation is consistent with previous studies indicating that most patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis do not experience decreases in educational or social functioning, reductions in quality of life, or severe residual symptoms.2,3

A study by Oczko-Grzesik et al6 reported that patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis experienced cognitive and affective symptoms before antibiotic treatment. The study did not evaluate patients after diagnosis; therefore, it is unknown whether these symptoms subsided after antibiotic treatment, as observed in our study.6 The reason for the increased receipt of psychiatric medications observed in our study is unknown, as the indications for the prescription of these medications were not available in the Danish National Prescription Registry.19 One possible explanation is that patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis also experience cognitive and affective symptoms6 for a definite period after diagnosis and antibiotic treatment. Because the indications for the prescription of psychiatric medications were not available in the prescription register, we could only speculate about the reasons for the increase in the receipt of antidepressant medications during the first year after a diagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis. The fact that the receipt of nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitors specifically increased within the first year after diagnosis and that nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitors are commonly prescribed for pain management suggests that pain management might be associated with the increased receipt of this particular type of psychiatric medication.1,25 This hypothesis is supported by the fact that nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitors are considered third-line therapy for depression based on worldwide guidelines, with which Denmark complies.26 The pain experienced by patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis may also partially explain the increased receipt of hypnotic and sedative medications among patients within the first year after diagnosis, as the nocturnal exacerbations of the painful meningoradiculitis associated with Lyme neuroborreliosis can produce sleep disturbances.27

In our study, patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis experienced no long-term increases in psychiatric disease, psychiatric hospitalization, or receipt of psychiatric medication, either overall or by subcategory. This finding is consistent with the favorable overall prognosis of patients after diagnosis with Lyme neuroborreliosis.2,3 The notion of a favorable prognosis with regard to psychiatric disease is supported by a study in which the proportion of individuals admitted to a psychiatric department who received positive results for B burgdorferi via serum testing was identical to that of blood donors from the same endemic area28 and by a study that reported no decrease in mental quality of life among patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis.29 In contrast, some studies have proposed an association between Lyme neuroborreliosis and psychiatric disease4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 and have suggested that a subgroup of patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis may experience a decrease in neuropsychological function.30 These studies, however, were either case-series studies5,9,10,11,31 or were limited by other factors, such as small study populations,4,6,7,8,30 vague case definitions, 4,8,32 or recruitment biases.4,8

Strengths and Limitations

This study had several strengths and limitations. Strengths include the study’s size and its nationwide population-based matched cohort design. Furthermore, the Danish National Prescription Registry provided unique and complete data on the burden of psychiatric diseases requiring medication, which are unlikely to be accessible at the individual level in most other settings.19 The data on psychiatric medication receipt is an additional strength of our study, as this outcome is likely to reflect all aspects of psychiatric disease, even mild to moderate disease, whereas data that relies on hospitalization reflect only moderate to severe disease. Data on cerebrospinal leucocyte count were unavailable, which may be a study limitation, as cerebrospinal pleocytosis is part of the diagnostic definition of definite Lyme neuroborreliosis.32 However, the inclusion of patients with a positive result on the B burgdorferi intrathecal antibody index test is a study strength, as a positive intrathecal antibody index test result is more accurate for the identification of patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis than is surveillance based on manually processed notifications and hospital discharge registries.33,34,35,36

One potential study limitation is that outcomes were compared between a patient cohort and a comparison cohort, and the comparison cohort could have included a larger proportion of individuals without diseases or hospital contacts. However, a previous study2 reported no differences in overall mortality and hospital contacts when Danish patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis were compared with individuals from the general population of Denmark. The fact that patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis were similar to individuals in the comparison cohort regarding the proportion of psychiatric hospital contacts and the receipt of prescribed psychiatric medications before study inclusion also indicates that the patient cohort was not more likely to have more frequent health care contacts than the comparison cohort. Furthermore, patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis and individuals in the comparison cohort had similar Charlson comorbidity index scores; thus, it is likely that the cohorts were similar in overall disease burden and were therefore similar in the percentage of hospital contacts. Another limitation was the lack of access to psychiatric disease testing scores. However, this limitation was partially mitigated by including analyses of psychiatric hospital contacts and the receipt of prescribed psychiatric medications.

Conclusions

The clinical implications of our study are notable in that no data were found to indicate an increase in the long-term risk of developing psychiatric disease after a diagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis. However, the short-term affective symptoms of Lyme neuroborreliosis warrant further investigation to assess the association between Lyme neuroborreliosis and the receipt of prescribed psychiatric medications.

eTable. Prescribed Psychiatric Medication From 3 Months Before Study Inclusion to 9 Months After Study Inclusion

eFigure. Percentage of Study Cohorts With Any Prescription for Antidepressant Medication per Year

References

- 1.Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 2012;379(9814):461-473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60103-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obel N, Dessau RB, Krogfelt KA, et al. . Long term survival, health, social functioning, and education in patients with European Lyme neuroborreliosis: nationwide population based cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k1998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haahr R, Tetens MM, Dessau RB, et al. . Risk of neurological disorders in patients with European Lyme neuroborreliosis. a nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;ciz997. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doshi S, Keilp JG, Strobino B, McElhiney M, Rabkin J, Fallon BA. Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among symptomatic patients with a history of Lyme disease vs two comparison groups. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(5):481-489. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallon BA, Nields JA. Lyme disease: a neuropsychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1571-1583. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oczko-Grzesik B, Kępa L, Puszcz-Matlinska M, Pudło R, Żurek A, Badura-Głąbik T. Estimation of cognitive and affective disorders occurrence in patients with Lyme borreliosis. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017;24(1):33-38. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1229002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajek T, Paskova B, Janovska D, et al. . Higher prevalence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in psychiatric patients than in healthy subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):297-301. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnco C, Kugler BB, Murphy TK, Storch EA. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in adults with Lyme disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;51:85-89. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bransfield RC Neuropsychiatric Lyme borreliosis: an overview with a focus on a specialty psychiatrist’s clinical practice. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6(3):104. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6030104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bransfield RC Suicide and Lyme and associated diseases. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1575-1587. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S136137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallon BA, Kochevar JM, Gaito A, Nields JA. The underdiagnosis of neuropsychiatric Lyme disease in children and adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21(3):693-703. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omland LH, Ahlstrom MG, Obel N. Cohort profile update: the Danish HIV Cohort Study (DHCS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(6):1769-9e. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roed C, Omland LH, Skinhoj P, Rothman KJ, Sorensen HT, Obel N. Educational achievement and economic self-sufficiency in adults after childhood bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1714-1721. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denmark Statistics website. Accessed October 11, 2019. http://www.statistikbanken.dk

- 15.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. . The Danish health care system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:563-591. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S179083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen CB The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kildemoes HW, Sorensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):38-41. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pottegard A, Schmidt SAJ, Wallach-Kildemoes H, Sorensen HT, Hallas J, Schmidt M. Data resource profile: the Danish National Prescription Registry. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449-490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gjerstorff ML The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):42-45. doi: 10.1177/1403494810393562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothman KJ Analyzing simple epidemiologic data In: Epidemiology: An Introduction. Oxford University Press; 2002:130-143. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ronning M, Blix HS, Harbo BT, Strom H. Different versions of the anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system and the defined daily dose—are drug utilisation data comparable? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56(9-10):723-727. doi: 10.1007/s002280000200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(7):CD008242. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008242.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer M, Pfennig A, Severus E, Whybrow PC, Angst J, Moller H-J; World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry; Task Force on Unipolar Depressive Disorders . World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders, part 1: update 2013 on the acute and continuation treatment of unipolar depressive disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(5):334-385. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2013.804195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hildenbrand P, Craven DE, Jones R, Nemeskal P. Lyme neuroborreliosis: manifestations of a rapidly emerging zoonosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(6):1079-1087. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nadelman RB, Herman E, Wormser GP. Screening for Lyme disease in hospitalized psychiatric patients: prospective serosurvey in an endemic area. Mt Sinai J Med. 1997;64(6):409-412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dersch R, Sarnes AA, Maul M, et al. . Quality of life, fatigue, depression and cognitive impairment in Lyme neuroborreliosis. J Neurol. 2015;262(11):2572-2577. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7891-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eikeland R, Ljostad U, Mygland A, Herlofson K, Lohaugen GC. European neuroborreliosis: neuropsychological findings 30 months post-treatment. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(3):480-487. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):305-310. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coumou J, Herkes EA, Brouwer MC, et al. . Ticking the right boxes: classification of patients suspected of Lyme borreliosis at an academic referral center in the Netherlands. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(4):368.e11-368.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dessau RB, Espenhain L, Molbak K, Krause TG, Voldstedlund M. Improving national surveillance of Lyme neuroborreliosis in Denmark through electronic reporting of specific antibody index testing from 2010 to 2012. Euro Surveill. 2015;20(28):21184. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.28.21184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Septfons A, Goronflot T, Jaulhac B, et al. . Epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis through two surveillance systems: the national Sentinelles GP network and the national hospital discharge database, France, 2005 to 2016. Euro Surveill. 2019;24(11):1800134. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.11.1800134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen K, Lebech AM. The clinical and epidemiological profile of Lyme neuroborreliosis in Denmark 1985-1990. a prospective study of 187 patients with Borrelia burgdorferi specific intrathecal antibody production. Brain. 1992;115(Pt 2):399-423. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.2.399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dahl V, Wisell KT, Giske CG, Tegnell A, Wallensten A. Lyme neuroborreliosis epidemiology in Sweden 2010 to 2014: clinical microbiology laboratories are a better data source than the hospital discharge diagnosis register. Euro Surveill. 2019;24(20):1800453. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.20.1800453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Prescribed Psychiatric Medication From 3 Months Before Study Inclusion to 9 Months After Study Inclusion

eFigure. Percentage of Study Cohorts With Any Prescription for Antidepressant Medication per Year