It has been more than a decade since Congress crafted and passed the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (TCA), which provided the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with broad authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products to protect public health.1 Given the disproportionate appeal of flavors to young people,2 the TCA included a key provision that banned flavors in cigarettes. Yet, the most popular flavor in cigarettes, menthol, was opportunistically exempted by Congress, who punted the issue to FDA’s Tobacco Product Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) to review the available scientific evidence and make a recommendation about menthol to the FDA. The exemption of menthol infuriated numerous health experts, who were not only concerned about young people, but also about the high rates of menthol use among Black smokers, resulting from decades of selective marketing of menthol cigarettes in Black communities by the tobacco industry.3 Indeed, a letter published in The New York Times by several former Health Secretaries eloquently stated “by failing to ban menthol, the bill caves to the financial interests of tobacco companies and discriminates against African Americans—the segment of our population at greatest risk for the killing and crippling smoking-related diseases. It sends a message that African American youngsters are valued less than white youngsters.” 4

In 2011, TPSAC finalized its report on menthol cigarettes and concluded that menthol in cigarettes increases initiation, facilitates progression to regular smoking, increases dependence, and decreases the likelihood of smoking cessation, especially among Black smokers, and as such, the removal of menthol from cigarettes would benefit public health.5 The tobacco industry successfully delayed FDA action on menthol by suing the agency in 2011, claiming that the TPSAC menthol report was flawed because several TPSAC members had conflicts of interest. Subsequently, the FDA conducted its own evaluation of menthol cigarettes in 2013 and came to similar conclusions regarding menthol’s harmful effects on initiation, dependence and cessation.6 Immediately thereafter7 and again in 2018,8 the FDA issued advance notice(s) of proposed rulemaking specific to menthol cigarettes, but action has been lacking.

The menthol exemption is a failure of the TCA, which was intended to protect public health. Although it is encouraging that cigarette consumption has declined 26% since the Act was signed, menthol has thrived in this declining market. The menthol market share has been increasing and 91% of the overall decline in cigarette consumption since the passage of the TCA is attributed to non-menthol cigarettes.9 This should not be surprising given that menthol facilitates smoking initiation, progression to regular smoking, and is a barrier to smoking cessation and sustained abstinence.5,6,10 Additionally, our analysis of data from the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) shows that a decade after Congress exempted menthol from the flavored cigarette ban, preference for menthol among cigarette smokers remains inversely correlated with age and extremely high among Black smokers (85%). It is important to note that in the context of inaction on menthol, young people and Black smokers are not the only vulnerable populations that warrant attention with respect to menthol smoking. Indeed, our analyses highlight that preference for menthol among cigarette smokers is also disproportionately high among lesbian, gay, and bisexual smokers, smokers with mental health problems, socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, and pregnant women (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Preference for Menthol Among Cigarette Smokers and Prevalence of Menthol Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States, 2018 (N = 56,175)

| Menthol preference among cigarette smokers | Menthol prevalence | |

|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 39.93 (38.33, 41.54) | 6.85 (6.49, 7.23) |

| Age | ||

| 12–17 years old | 49.70 (43.13, 56.30) | 1.28 (1.03, 1.58) |

| 18–25 years old | 48.85 (46.98, 50.72) | 9.23 (8.62, 9.87) |

| 26–34 years old | 47.82 (44.54, 51.13) | 12.32 (11.53, 13.17) |

| 35–49 years old | 38.74 (36.38, 41.15) | 8.44 (7.77, 9.15) |

| 50–64 years old | 33.14 (29.22, 37.32) | 6.19 (5.39, 7.10) |

| 65 years old or older | 29.21 (24.01, 35.01) | 2.66 (2.13, 3.32) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| NH White | 29.35 (27.79, 30.97) | 5.52 (5.17, 5.89) |

| NH Black | 84.62 (81.84, 87.03) | 15.06 (13.78, 16.43) |

| NH Asian | 46.76 (36.22, 57.61) | 10.15 (7.59, 13.46) |

| NH AI/AN or NHOPI | 35.37 (26.72, 45.09) | 3.69 (2.53, 5.37) |

| NH more than one race | 51.45 (42.16, 60.63) | 11.95 (9.24, 15.32) |

| Hispanic | 49.97 (45.64, 54.29) | 6.24 (5.65, 6.88) |

| Sexual identity | ||

| Heterosexual | 38.96 (37.25, 40.69) | 7.07 (6.67, 7.50) |

| Lesbian/gay | 51.39 (42.07, 60.62) | 12.74 (10.15, 15.87) |

| Bisexual | 45.93 (40.88, 51.07) | 14.32 (12.40, 16.48) |

| Poverty status | ||

| Living in poverty | 46.78 (43.62, 49.97) | 12.24 (11.30, 13.24) |

| Income up to 2× Federal Poverty Threshold | 42.33 (39.26, 45.46) | 9.38 (8.61, 10.22) |

| Income more than 2× Federal Poverty Threshold | 35.78 (33.25, 38.40) | 4.98 (4.51, 5.30) |

| Receives government assistance | ||

| Yes | 45.88 (42.71, 49.07) | 13.59 (12.55, 14.72) |

| No | 37.19 (35.48, 38.92) | 5.35 (5.05, 5.66) |

| Past month serious psychological distress | ||

| Yes | 45.29 (40.84, 49.82) | 17.01 (15.27, 18.90) |

| No | 39.03 (37.28, 40.81) | 6.79 (6.39, 7.22) |

| Pregnant (women only) | ||

| Yes | 60.12 (44.63, 73.83) | 6.96 (4.88, 9.84) |

| No | 51.36 (49.09, 53.62) | 8.61 (8.07, 9.19) |

All data were weighted to be nationally representative and adjust for complex sampling. Menthol use was asked among past-30-day cigarette smokers with the following question: “Were the cigarettes you smoked during the past 30 days menthol?” (yes/no).AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; CI = confidence interval; NH = non-Hispanic; NHOPI = Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

Source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2018.

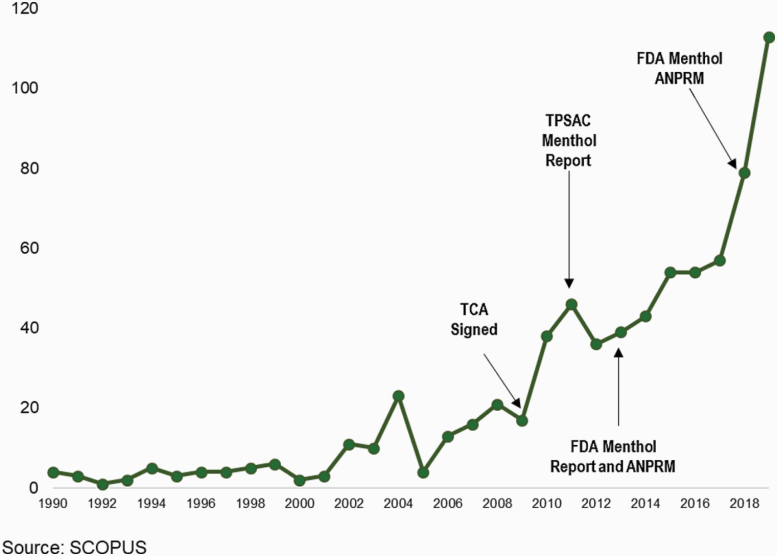

It bears mention that the research literature on menthol cigarettes was limited prior to the signing of the TCA. Moreover, as shown in Figure 1, it appears that the signing of the TCA, with its menthol exemption—combined with TPSAC’s review of the science—spurred research on this topic. Of note, the evidence base on menthol cigarettes has considerably accelerated in recent years and is considerably more robust today than a decade ago. This issue of Nicotine and Tobacco Research contains several such articles11–14 that explore various aspects of menthol from diverse methodological perspectives. In his review article on the biological impact of menthol on dependence, Wickman comments that “selectively marketing a more dangerous product to select populations highlights that menthol cigarettes pose not just a public health problem, but a social justice problem as well.” 14 We wholeheartedly agree and in the context of social justice and menthol cigarettes, the findings from these studies merit attention.11,13

Figure 1.

Number of menthol cigarette articles published annually: 1990–2019 (n = 716).

Abbreviations: ANPRM, Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking; TCA, Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; TPSAC, Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee.

Using data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey, Sawdey and colleagues found that although menthol use has declined overall among youth from 2011 to 2018, there was no decline in menthol use among Black and Hispanic students.12 Compared with non-menthol smokers, menthol smokers perceived less harm associated with smoking, experienced higher levels of craving and were more likely to reside in a household where a family member smokes. This study demonstrates that despite population-level declines in menthol use, menthol use persists among racial/ethnic minority youth.

Pregnant women represent a uniquely vulnerable population, and the prevalence of cigarette smoking during pregnancy has remained stable over the past decade in the United States and has increased among pregnant women with depression.15 Little is known about use of menthol cigarettes in this population. In two longitudinal samples of racially and ethnically diverse, low socioeconomic status pregnant smokers recruited from obstetric clinics, Stroud and colleagues found extremely high rates of menthol use (≥85%) among pregnant smokers, as well as lower quit rates among those who smoked menthol versus non-menthol.13 The findings from this study, combined with our own analyses, suggest that assessing menthol smoking status should be a priority in all substance use research and smoking cessation interventions for pregnant women. Moreover, critical research is needed to assess the impact of menthol smoking on cessation during pregnancy and subsequent impact on health outcomes of both mother and offspring. This is paramount given the huge Black–White infant mortality gap in the United States.16 It is plausible that menthol could be exacerbating these deep social inequities.

The menthol loophole and subsequent inaction on menthol comes down to policy makers, political influence, and power. We cannot help but consider the counterfactual—would menthol be banned if the typical consumer was young, White and upper-middle class? Consider the efforts of “Parents against Vaping E-cigs” or PAVe17—an advocacy group created in 2018 led by three White mothers—to stamp out youth e-cigarette use. We can only speculate that tobacco use was a non-issue in their communities until Juul came along. In the short time since their creation, PAVe has been given a platform to advocate against e-cigarettes; they have mobilized numerous localities and have had the opportunity to testify before Congress and meet with President Trump at the White House. Already, four states ban flavored e-cigarettes, yet only one of them (Massachusetts) also banned more risky flavored combustible products, like menthol cigarettes. This is despite efforts from numerous advocacy groups and organizations, such as the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council and the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network.

A ban on menthol cigarettes could have monumental implications for both the short- and long-term physical and mental health of communities of color. Of note, a 2011 study modeling the effects of a menthol ban in the United States estimated that 633 252 deaths would be averted and that one of three of these would be a Black life.18 When it comes to menthol, we urge policy makers to take action once and for all and ban menthol for the protection of public health and to achieve health equity. Tobacco control advocates focused on e-cigarettes must consider that their short-term wins (eg, flavored e-cigarette ban) can result in long-term damage to vulnerable communities if menthol cigarettes remain neglected. Health care providers and tobacco-dependent treatment specialists must assess menthol smoking among their patients and work toward developing smoking cessation therapies that are effective for menthol smokers.14 And lastly, researchers must not only continue with work that further examines the impact of menthol cigarettes on vulnerable populations, they must also engage in active dissemination with policy makers to push for a ban on menthol. As the Health Secretaries noted more than a decade ago when Congress caved to the financial interests of tobacco companies and exempted menthol from the TCA, “we do everything we can to protect our children in America, especially our white children. It’s time to do the same for all children.” 4

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R21 HL149773-01 to R.D.G.) and the Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science, National Cancer Institute, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (U54CA229973 to C.D.D. and O.G.). This work was also supported in part by the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey (P30CA07270 to O.G.). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Melody Wu for reviewing this editorial.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. In Public Law No. 111–31. Vol. HR 12562009.

- 2. Villanti AC, Johnson AL, Ambrose BK, et al. Flavored tobacco product use in youth and adults: findings from the first wave of the PATH Study (2013–2014). Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(2):139–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Cancer Institute. A Socioecological Approach to Addressing Tobacco-Related Health Disparities. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph 22. NIH Publication No. 17-CA-8035A. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Text of Letter to Senators on Menthol Exemption for Cigarettes. The New York Times. June 5, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tobacco Product Scientific Advisory Committee. Preliminary Scientific Evaluation of the Possible Public Health Effects of Menthol Versus Nonmenthol Cigarettes https://www.fda.gov/media/86497/download. Published 2011. Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Reference Addendum to the “Preliminary Scientific Evaluation of the Possible Public Health Effects of Menthol Versus Nonmenthol Cigarettes.” https://www.fda.gov/media/86409/download. Published 2013.

- 7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Menthol in Cigarettes, Tobacco Products; Request for Comments, 21 C.F.R. § 1140 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on Proposed New Steps to Protect Youth by Preventing Access to Flavored Tobacco Products and Banning Menthol in Cigarettes [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Villanti AC. Assessment of menthol and nonmenthol cigarette consumption in the US, 2000 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2013601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Villanti AC, Collins LK, Niaura RS, Gagosian SY, Abrams DB. Menthol cigarettes and the public health standard: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gunawan T, Juliano LM. Differences in smoking topography and subjective responses to smoking among African American and White menthol and non-menthol smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(10):1718–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sawdey MD, Chang JT, Cullen KA, et al. Trends and associations of menthol cigarette smoking among US middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011–2018. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(10):1726–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stroud LR, Vergara-Lopez C, McCallum M, Gaffey AE, Corey A, Niaura R. High rates of menthol cigarette use among pregnant smokers: preliminary findings and call for future research. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wickham RJ. The biological impact of menthol on tobacco dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(10):1676–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goodwin RD, Cheslack-Postava K, Nelson DB, et al. Smoking during pregnancy in the United States, 2005–2014: the role of depression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;179:159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirby RS. The US black-white infant mortality gap: marker of deep inequities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):644–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parents Against Vaping E-Cigarettes. Parents Against Vaping E-Cigarettes (PAVe). https://www.parentsagainstvaping.org/. Accessed August 8, 2020.

- 18. Levy DT, Pearson JL, Villanti AC, et al. Modeling the future effects of a menthol ban on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(7):1236–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.