Abstract

Background

Mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs) are the world’s leading cause of years lived with disability; in low-and-middle income countries (LIMCs), the treatment gap for SUDs is at least 75%. LMICs face significant structural, resource, political, and sociocultural barriers to scale-up SUD services in community settings.

Aim

This article aims to identify and describe the different types and characteristics of psychosocial community-based SUD interventions in LMICs, and describe what context-specific factors (policy, resource, sociocultural) may influence such interventions in their design, implementation, and/or outcomes.

Methods

A narrative literature review was conducted to identify and discuss community-based SUD intervention studies from LMICs. Articles were identified via a search for abstracts on the MEDLINE, Academic Search Complete, and PsycINFO databases. A preliminary synthesis of findings was developed, which included a description of the study characteristics (such as setting, intervention, population, target SUD, etc.); thereafter, a thematic analysis was conducted to describe the themes related to the aims of this review.

Results

Fifteen intervention studies were included out of 908 abstracts screened. The characteristics of the included interventions varied considerably. Most of the psychosocial interventions were brief interventions. Approximately two thirds of the interventions were delivered by trained lay healthcare workers. Nearly half of the interventions targeted SUDs in addition to other health priorities (HIV, tuberculosis, intimate partner violence). All of the interventions were implemented in middle income countries (i.e. none in low-income countries). The political, resource, and/or sociocultural factors that influenced the interventions are discussed, although findings were significantly limited across studies.

Conclusion

Despite this review’s limitations, its findings present relevant considerations for future SUD intervention developers, researchers, and decision-makers with regards to planning, implementing and adapting community-based SUD interventions.

Keywords: Community-based mental health, Mental health, Community psychiatry, Implementation, Substance use disorder, Psychosocial, Alcohol use disorder

Key points.

A narrative literature review was conducted to identify and describe the different types and characteristics of psychosocial community-based substance use disorder (SUD) interventions in LMICs, as well as the context-specific factors that could have influenced the interventions.

Ten out of the 15 included studies were published in or after 2015, suggesting that there has been a relatively recent increase in efforts to implement and/or study community-based SUD interventions in LMICs.

None of the included studies were conducted in a low-income country. Ten interventions were implemented in Asia, six interventions in Africa, one intervention in Eastern Europe, and two in South America.

Screening and brief intervention (SBI) interventions were proportionately the most commonly implemented. The most common intervention delivery settings were primary health care centers, hospital out-patient settings, neighborhoods and specialized SUD treatment settings.

Most of the reviewed interventions were somehow related to other priority conditions or issues (i.e. integrated interventions), such as sexual behaviors, HIV, tuberculosis (TB), pregnancy, and intimate partner violence (IPV).

Based on the sociocultural factors that influenced some interventions, authors recommended that future interventions should be adapted to improve acceptability by female populations, enhance help-seeking behaviors, and focus more on specific substance use patterns per setting.

Background

Global mental health

Quality and accessible mental health services, including substance use disorder services, in low-resource settings are increasingly being recognized as issues of global importance [1–3]. In 2016, the adoption of the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) pushed for the prioritization of focused action in the field of mental healthcare and substance abuse treatment and prevention [1, 3]. The inclusion of mental health and well-being in the SDGs was motivated by previous calls for action and research findings urging to increase the level of care for mental and substance use disorders [3–5]. Mental health and substance use disorders are the world’s leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) and account for 183.9 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [6]. Moreover, substance use disorders can best be understood as primarily mental health conditions; SUDs are often treated by mental health professionals in specialized clinics, hospitals, or out-patient treatment programs.

In low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) the treatment gap for mental disorders is between 76 and 85%, meaning that at least three fourths of people with a mental disorder do not receive treatment [2]. In this context, two key objectives outlined in the WHO Mental Health Action Plan and the UN SDGs are to scale-up community-based mental health services and “strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse” [1, 2].

Low-and-middle income countries (LMICs) are defined as those classified as such by the World Bank [7]. Research has shown that the insufficient quality, availability, and funding for mental and substance use disorder services is a significant barrier for the improvement of mental health systems in LMICs [8, 9]; high-income countries (HICs) spend up to twenty times more than low-income countries on mental health-related prevention, treatment, management, and educational programs [10]. Stakeholders in LMICs believe that four mechanisms are key in order to increase the availability and quality of mental health services: the de-centralization of psychiatric institutions, the implementation of community-based mental health services, the increased availability of adequately trained and supervised mental health staff, and the incorporation of mental health care into primary care settings and general hospitals [11]. Addressing these barriers will be essential in order to narrow the current treatment gap and improve services for mental and substance use disorders in LMICs, and with that reduce the disproportionately high burden of disease due to mental disorders in these settings.

Barriers to the scaling up of substance abuse treatment and prevention efforts in LMICs include a low prioritization of the problem, an inability to detect and treat non-severe substance use disorders at an early stage and in the community, and lower help-seeking by affected populations due to fear of stigma or normative cultural views on substance use [12–17]. These persistent political, structural, and sociocultural issues continue to obstruct efforts to provide effective and equitable care services to the mental health populations most in need of them in LMICs [8, 11, 18, 19].

Substance use disorders in low-and-middle income countries

People suffering from psychoactive substance use disorders (SUDs) make up a large portion of the underserved mental health population, accounting for at least 20.5% of the 183.9 million DALYs due to mental disorders [6]. This review defines SUDs according to the ICD-10 classification, that is, “mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use” including acute intoxication, harmful use, dependence syndrome, withdrawal state, withdrawal state with delirium, psychotic disorder, amnesic syndrome, and residual late-onset psychotic disorder [20]. Psychoactive substances include alcohol, opioids, cannabinoids, sedatives, cocaine, stimulants, hallucinogens, tobacco and volatile solvents [20].

This review focuses on SUDs related to alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, opioid, and amphetamine-type stimulant use, as these have a greater correlation with treatment entry and with comorbidity with other mental disorders [6, 21]. Treatment gap estimates for substance use disorders in LMICs range from 75–95%, with the gap being greater in rural areas [16, 17, 22, 23]. SUD-affected populations in LMICs are two to ten times less likely to receive minimally adequate treatment (defined as the minimum number of visits to treat a disorder) and those with a SUD in these settings are less able to recognize their need for treatment than their HIC counterparts [12, 21]. Further, although harmful alcohol use contributes to a greater portion of the alcohol-related harm in LMICs than alcohol dependence, many LMICs place a greater focus on detecting and treating alcohol dependence; as a result, harmful/hazardous drinkers are often not identified early on and receive care only when their condition has progressed significantly [24]. Although the same cannot be said with regards to illicit substance use due to a lack of data globally, it has been mentioned that “there is a need to improve our understanding of these basic epidemiological questions about illicit drug use and dependence in order to improve our capacity to respond” [25]. In this context, prioritizing efforts to screen for and treat harmful substance use would present significant benefits to LMICs (i.e. by reducing alcohol-related harm, improving prevention of dependence, and generating previously lacking epidemiological data).

The barriers toward the scale-up of SUD treatment and prevention in LMICs may also be related to how SUDs are formally conceptualized and addressed in these settings. The criminalization of illicit substance use poses unique challenges to the field of public health as it not only limits the range of possible SUD treatment or prevention services in a given setting, but it may also increase the negative health effects and other health risks (e.g. of intimate partner violence, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis) among drug-using populations [26–30]. Only recently—in 2016, at the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on drugs—have more countries agreed to recognize SUDs as “complex multifactorial health” disorders and begun to shift from a punishment approach towards a public health approach [31]. However, despite this step in the right direction, there remain significant knowledge and implementation gaps in the field of SUD care in LMICs, with actions still largely limited to the dissemination of recommendations and materials [26, 31].

Substance use disorder treatment and prevention

The ecology of SUDs involves “intrapersonal, inter-personal, and broader systems-level processes” which, from a public health perspective, should each be addressed sufficiently [32, 33]. As mentioned previously, SUDs may range from mild (acute intoxication and harmful use) to severe (dependence and withdrawal syndrome), which means that different intervention types, intervention settings, and intervention intensities are necessary to address the care needs of the entire SUD population [32, 34]. Persons with SUDs may receive treatment through specialized treatment settings such as in-patient detoxification and rehabilitation services, through residential treatment and therapeutic communities, through other mental health services, mutual help organizations, or through outpatient hospital and primary care services; however, there is limited information about the arrangement and functioning of such services in LMICs [13, 15].

An ‘indicated prevention’ approach is recommended to prevent the further development of the disorder in cases of harmful substance use [35], that is, a pattern of use not yet characterized as dependence but which causes physical or mental damage to health [20]. Indicated prevention interventions may be defined as brief “client-centered, goal-oriented” psychosocial interventions with educational and motivational components; they have shown positive results in LMICs when delivered by a non-specialized, primary care workforce in rural and community settings [35]. That said, there is currently insufficient evidence about what intervention models and characteristics may be suitable to address the needs of various SUD populations in LMICs.

Substance use disorder interventions may be pharmacological and/or psychosocial in nature. Pharmacological interventions are normally delivered during the early stages of treatment and involve using antagonist and withdrawal-reducing medications to alleviate withdrawal symptoms and facilitate treatment adherence for physically dependent individuals [32, 36, 37]. Psychosocial SUD interventions are usually face-to-face interventions that focus on the psychological and social aspects of a person’s life [38, 39]. Examples of psychosocial SUD interventions include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), brief interventions (including indicated prevention interventions), interpersonal therapy, self-help groups, family therapy, motivational interviewing, and relapse prevention [34, 38]. Lastly, the sociocultural environments in which interventions are delivered may further affect their effectiveness and implementation (e.g. feasibility and acceptability); studies have shown that culturally-adapting psychosocial SUD interventions may result in improved implementation outcomes by addressing context-specific factors such as stigma, ethnicity and cultural beliefs [40–44]. So far, there is limited evidence about the extent to which SUD interventions are culturally adapted in LMICs or about the facilitators, barriers, or common elements involved in this process.

Community-based SUD interventions

Community mental health and SUD interventions present significant advantages for mental health service users and systems in LMICs such as reduced costs, greater reach, decreased stigma, and improved quality of life and community functioning for affected populations [32, 45–47]. This review defines community-based mental health interventions as decentralized interventions integrated into primary care settings or general hospitals which are supported by collaborations between a range of stakeholders (formal and informal) and which aim to facilitate independent community functioning and rehabilitation through education, self-care, “goal setting, skills development, and… access to community and environmental resources” [2, 48]. Based on this definition, examples of community-based mental health and SUD interventions may include psychosocial interventions delivered through community facilities, outpatient care settings or mental health centers, “support of people with mental disorders living with their families, supported housing”, assertive community treatment, and pharmacological and harm-reduction interventions [2, 47].

There seems to be a growing number of efforts to implement community-based SUD services in LMICs that are responsive to context-specific needs, possibilities, and barriers [35, 49–51]. Although this topic has not has not yet been systematically investigated, previous individual studies from LMICs have demonstrated that various resource, sociocultural and/or political factors may influence the development, implementation and/or outcomes of community-based SUD interventions [35, 49, 50, 52]. Therefore, an initial attempt to systematically identify and describe the relevant contextual factors that may affect community-based SUD interventions in LMICs seems warranted.

In summary, considering the high prevalence of SUDs in LMICs and the discussed barriers to scale-up SUD services in these settings, there has been an increased demand to implement cost-effective community-based SUD interventions in LMICs. However, the translation into practice is still lacking and research on this matter, especially in relation to psychosocial interventions, remains scarce and limited to high-income settings [2, 32, 35].

Aims

This review aimed to identify and describe the different types and characteristics of psychosocial community-based SUD interventions in LMICs, and explore what context-specific factors (i.e. policy, resource, sociocultural) may influence such interventions in their design, implementation, and/or outcomes.

Methods

A narrative literature review was conducted on community-based substance use disorder intervention studies from LMICs. This method was seen as the most suitable research design because such reviews seek to identify and discuss information from various sources about relatively broad topics, topics that have not-yet been sufficiently addressed, and/or topics for which quantitative meta-analysis would not be the suitable [53, 54]. This review followed a systematic data collection process using a defined set of criteria and standardized data extraction tools, which are recommended in order to minimize bias and increase the quality of narrative reviews [54]. For the PRISMA checklist, see Additional file 1: Appendix S4.

The narrative synthesis process for this review was inspired by the Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews (CNSSR) [55]. First, a preliminary synthesis of the intervention characteristics was developed and presented through textual descriptions and tabulation. Thereafter, a content and brief thematic analysis was conducted based on the (manually) coded data extracted from the included studies. The data coding process used both deductive and inductive coding techniques [56–58].

Eligibility criteria

Tables 1 and 2 outline the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review based on the PICOS model (participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design). Since the aim of this review was to identify and describe the characteristics of community-based SUD interventions, all study designs were included if they contained a description of the intervention and the process of implementation. No limits were placed on study comparisons or reported outcomes to ensure that the greatest variety of interventions were included.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria item | Description | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

Persons aged 16–65 in LMICs identified as having a psychoactive substance use disorder due to alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulants, or opiate use, with or without formal diagnosis Substance users aged 16–65 considered to be at-risk for SUDs |

Alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulant and opiate use have a greater correlation with treatment entry and other mental disorders [6, 21] Considering the lack of a sufficiently trained and qualified mental health workforce in LMICs, and considering that a key focus in LMICs is the delivery of mental health services by non-specialized community workers, placing limits on the source of diagnoses or diagnostic standard would limit the relevance of this review and likely reduce the number of eligible studies |

| Intervention |

Community-based treatment and/or indicated prevention interventions with a psychosocial component, such as: Assertive community treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), brief interventions, indicated prevention interventions, interpersonal therapy, self-help groups, family therapy, motivational interviewing, and/or relapse prevention Interventions delivered in primary care settings such as primary health care centers or general hospital out-patient services, mental health centers (including day care centers), self-help group settings, social/housing services and vocational support services |

The development of SUDs involves complex “intrapersonal, inter-personal and broader systems-level processes” which pharmacological interventions, hospital-based interventions and/or campaigns alone do not sufficiently address [27] The recommended good practice for the treatment of SUDs is a biopsychosocial approach, which considers “genetic, psychological, social, economic, [and] political factors” [26, 28] This study sought to explore the influence of context-specific factors on the development, implementation and outcomes of SUD interventions in LMICs; There is a high treatment gap for SUDs in community and rural settings; A significant portion of the SUD population (i.e. harmful users) receive insufficient or no care, such populations would benefit from lower intensity interventions and indicated prevention interventions which may be delivered in primary care settings and in the community |

| Comparisons and outcomes | All reported outcomes | To ensure that the greatest variety of interventions were included, which is of relevance for this review as it sought to identify and describe the characteristics of community-based SUD interventions |

| Study design | Qualitative, mixed-methods, and quantitative studies such as descriptive studies, research case studies, pre-post trials, RCTs and evaluation studies | The data relevant to this review’s aims may be obtained from various study designs, placing limits on the types of studies would limit the relevance of this review |

| Articles | English-language articles published in academic journals that follow a peer-review publication process |

The timeline for this review was restricted; broadening the criteria to include grey literature would not be feasible Although this review did not assess risk of bias or evidence quality, it did seek to identify ethically conducted research studies that have gone through a peer-review publication process (required for publication in peer-reviewed journals) |

| Publication date | 2008–2019 | Due to the infancy of the field and relatively recent calls for action on matters relating to the focus of this review [2, 31, 59] |

Table 2.

Exclusion Criteria

| Exclusion criteria item | Description | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention |

Policy or guideline implementation studies Pharmacological interventions without a psychosocial component |

The inclusion of these types of interventions would result in data that is too heterogenous for a narrative review Although these types of interventions (policies, guidelines, and pharmacological) may address current priorities in the field, they do so in a different context and through means which are not directly focused on the individual and psychosocial factors involved in the development and treatment of SUDs |

| Target population | Populations without a SUD such as families, carers, and the general population | For reasons of feasibility and relevance. Although interventions for families and general populations are relevant efforts towards addressing SUDs in LMICs, they are fundamentally and practically different from interventions developed for SUD populations; including them would not be feasible, it would unrealistically broaden this review’s scope, and it would reduce its relevance due to the heterogeneity among interventions |

To be included, interventions had to be psychosocial face-to-face interventions delivered in community settings as described in the background section of this manuscript. Interventions had to be targeted at people identified as having a psychoactive substance use disorder due to alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, opiate, or amphetamine-type stimulant use with or without a formal diagnosis; this was to ensure that all interventions for these populations were included regardless of resource limitations or differences in diagnostic materials/standards used [35, 46, 59]. Prevention intervention studies were only included if they fit the criteria for “indicated prevention” according to Kane and Greene, that is, “programs that are targeted towards those who are not only at higher risk for an outcome but who have signs and symptoms… of the outcome itself [i.e. substance use, acute intoxication, harmful use]” [35]. Interventions targeting vulnerable populations, such as HIV-positive populations, were only included if these populations (or a sub-set thereof) also had a SUD and if the interventions also targeted the SUD. As this is an exploratory review, no limits were placed on reported outcomes and no risk of bias assessment was conducted.

Data collection

Articles were obtained via a search for abstracts on the MEDLINE, Academic Search Complete and PsycINFO databases using the EBSCOHOST online repository [60–62]. The search terms used were based on this study’s inclusion criteria and the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) substance-related disorders, community health services, primary health care, psychiatric rehabilitation and community psychiatry. In addition, the search string used for this review was informed by terms used in previous reviews relevant to this research topic [35, 42, 63–66]. In summary, the search string used in this review covered four key concepts for which related terms were used: (1) psychoactive substance use disorders, (2) psychosocial intervention, (3) community-based, and 4) low-and middle-income country. Additional file 1: Appendix S1 outlines the search string used for this review and special limiters applied.

After duplicates were removed, all abstracts were screened using a screener sheet (Additional file 1: Appendix S2) that was based on this review’s inclusion criteria to determine if articles may be eligible for inclusion. When there were uncertainties about the eligibility of articles, these were discussed with and reviewed by a second reviewer (BJHW, the second author of this manuscript).

Data coding and analysis

A data capture sheet (Additional file 1: Appendix S3) was developed based on the screener sheet and previously developed materials [67–69] to further inform inclusion decisions and ensure the systematic collection of relevant data. Thus, the data capture sheet served as the coding framework for this review and facilitated the systematic identification of the main study characteristics.

The pre-defined topics used for deductive coding were those that focused on what/how policy, resource, or sociocultural factors influenced interventions in their design, implementation, and/or outcomes [55, 56]. Context-specific barriers and facilitators were initially defined as the sociocultural, political or resource factors that were reported by the authors to have had an impact on the interventions’ design, implementation and/or outcomes. However, early in the coding process it became apparent that the authors’ discussions of these factors in the context of barriers and/or facilitators were significantly limited across studies. Therefore, to allow for some description and analysis of these contextual factors, the data extraction approach was expanded to include any discussion of political, resource, sociocultural and/or implementation factors that may have played a role, either explicitly or implicitly, in the rationale for, planning, delivery, and/or outcomes of the interventions (see Additional file 1: Appendix S3). Lastly, any additional or emerging themes from the extracted data were identified and discussed [56].

Results

Included articles

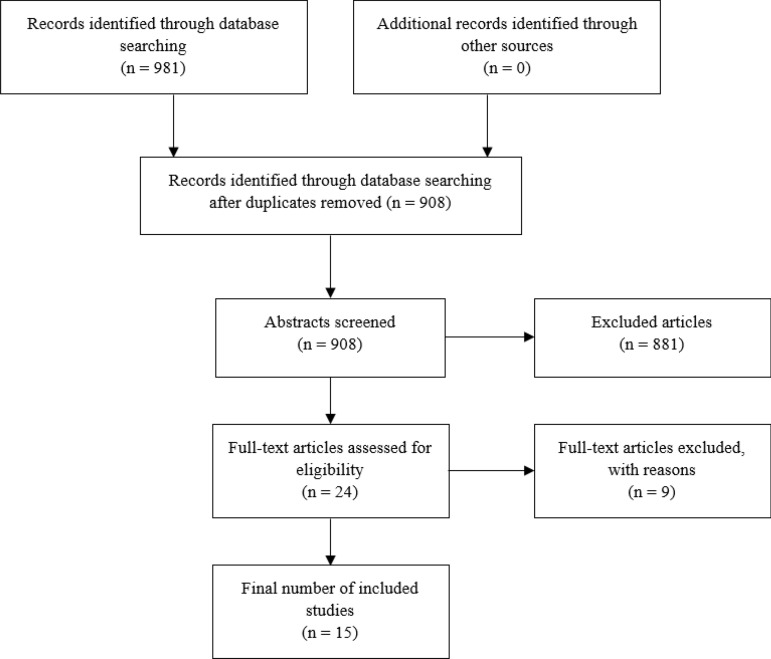

Figure 1 shows the article selection process of this review according to PRISMA guidelines. Out of 908 abstracts screened, 24 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility; out of these 24, nine articles were cross-checked for eligibility by a second reviewer and eventually excluded. Finally, a total of 15 articles were included for this review. Ten out of the 15 included studies were published in or after 2015, suggesting that there has been a relatively recent increase in efforts to implement and/or study community-based SUD interventions in LMICs. Table 3 presents the key characteristics of the included studies, and Table 4 a description of the interventions and a summary of their findings. The italicized text in Tables 3, 4, and 5 are direct quotations that have been extracted from the included studies.

Fig. 1.

Screening and selection of eligible studies

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies

| References | Setting | Study design and objectives | Target population/s and condition | Intervention objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeida do Carmo et al. [87] | Sao Paulo, Brazil | Cross-sectional retrospective to evaluate the effects of a recovery housing and social reintegration program for people recovering from substance dependence | 69 persons ages ≥ 18 in recovery from substance dependence, abstinent after discharge from detoxification (alcohol, crack cocaine, marijuana) | Reintegration into society by helping users enter employment, achieve autonomy, remain abstinent and adhere to treatment |

| Assanangkornchai et al. [86] | Four district hospitals and four healthcare centers in two provinces in Southern Thailand | RCT to assess the effectiveness of the WHO ASSIST-BI [78] procedure compared with ASSIST-screening followed by simple advice (SA) in primary care in low-population areas | 236 persons ages ≥ 16 identified as problem or risky substance users (alcohol, amphetamine-type substances, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives and other substances) | Improve identification of substance misuse and provide support for users to understand their risky SU and develop abstinence strategies |

| Humeniuk et al. [71] |

Australia: walk-in sexually transmitted disease clinic. Brazil: 30 primary health care (PHC) units, two health centers and one out-patient setting India: community health centers in Shadipur. United States: community clinic |

RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of a BI [brief intervention] for illicit drugs [cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) and opioids] in PHC clients; determine whether a BI targeted at one substance would increase use of another substance, evaluate whether the general severity of substance involvement affects the response to a BI | 731 persons who scored between 4 and 26 on the ASSIST (moderate-risk range) for cannabis, cocaine, ATS or opioids | Reduce risky substance use (SU) in PHC clients using the WHO ASSIST and its linked brief intervention |

| Kane et al. [70] | Three high-density, low-resource areas in Lusaka, Zambia | RCT protocol (trial completed). The primary aims of the trial are to evaluate the effectiveness of the adapted CETA intervention on (a) reducing and preventing women’s experience of intimate partner violence (IPV) and (b) reducing male partner’s hazardous alcohol use | Hazardous alcohol use and intimate partner violence. Family ‘units’ consisting of three individuals: an adult woman, her male husband or partner (who must be a hazardous drinker according to AUDIT scores), ages ≥ 18, and one of her children (male or female, ages 8–17) | CETA: an adaptable mental health intervention that targets cognitive and behavior change through a variety of intervention components. CETA was specifically adapted in this intervention to be delivered in group settings and to include a CBT-based substance use (SU) reduction element |

| Lancaster et al. [76], data also extracted from sister article Miller et al. [77] | Kyiv, Ukraine (one community site), Thai Nguyen, Vietnam (two district health center sites), and Jakarta, Indonesia (one hospital site) | Two-arm RCT designed to determine the feasibility, barriers and uptake of an integrated intervention combining health systems navigation and psychosocial counselling for the early engagement and adherence of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and medication-assisted treatment for substance use (MAT) for people who inject drugs (PWID) living with HIV |

People who inject drugs (PWID) more than 12 times per 3 months (n = 502), who were HIV-positive (viral load of 1000 copies) and their non-infected injection partners (n = 806) were recruited as network units. Ages 18–60 Conditions: intravenous substance use and HIV |

Harm reduction, improved retention and adherence to SU treatment and HIV care, psychosocial counselling, and referral for ART at any CD4 count |

| L’Engle et al. [75] | Three health drop-in centers in Mombasa, Kenya | RCT to assess whether a brief alcohol intervention leads to reduced alcohol use and sexually transmitted infection (STI)/HIV incidence and related sexual risk behaviors among moderate drinking female sex workers |

Population: Female sex workers of ages ≥ 18 with hazardous drinking (AUDIT score 7–19) Conditions: Alcohol use disorder and STIs |

Brief intervention based on WHO Brief Intervention for Alcohol Use. The main objective was to facilitate change/reduction in drinking and risky sexual behaviors |

| Nadkarni et al. [82] | Eight primary health centers in Goa, India |

To study and describe the development of the Counselling for Alcohol Problems (CAP) brief intervention Methods: Three steps are described—(i) identifying potential treatment strategies; (ii) developing a theoretical framework for the treatment; and (iii) evaluating the acceptability and feasibility of the treatment (through a pilot RCT comparing CAP with enhanced usual care (EUC)) |

Males ages ≥ 18 who had a clinical diagnosis of AUD from a mental health professional or who scored 12+ on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) | Reduce harmful drinking behaviors through CAP delivery in primary care services by trained non-professionals |

| Nadkarni et al. [73] | Ten primary health centers in Goa, India | Single-blind individually randomized trial comparing counselling for alcohol problems (CAP) plus enhanced usual care (EUC) versus EUC only | Alcohol dependent males (AUDIT score of 20 or above) 18–64 years old |

Investigate the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of: identifying and recruiting men with probable AD [alcohol dependence] in primary care; delivering a brief treatment for AD by lay counsellors in primary care CAP intervention was used to treat alcohol dependence in primary care |

| Noknoy et al. [72] | Eight primary care units (PCU) in rural Northeast (n = 7) and central (n =1) Thailand | RCT to determine the effectiveness of Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) for hazardous drinkers in PCU settings | Hazardous drinkers ages ≥ 18 (AUDIT score of 8 or more) | Reduce alcohol consumption among hazardous drinkers in Thailand and harmful drinking behaviors |

| Pan et al. [88] | Four community-based Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) clinics in Shanghai, China | RCT to determine [1] whether CBT is effective in improving treatment retention and reducing drug use for opiate-dependent Chinese patients in MMT and [2] whether CBT is effective in decreasing addiction severity and psychological stress for MMT patients. Control group were patients receiving MMT alone | Opiate dependent patients according to psychiatrist diagnosis with DSM-IV. Ages 18–65 | Cognitive behavioral therapy alongside methadone maintenance treatment to improve treatment adherence and decrease severity of SUD |

| Papas et al. [83], data also extracted from Papas et al. [43] | HIV outpatient clinic in Eldoret, Kenya | RCT of a culturally adapted Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected outpatients | Persons ages ≥ 18, enrolled as HIV outpatients (receiving or eligible to receive antiretroviral) who satisfy the hazardous or binge drinking criteria (score ≥ 3 on the AUDIT-C, or ≥ 6 drinks per occasion at least monthly | Culturally adapted CBT to achieve abstinence from alcohol and/or encourage approximations to abstinence |

| Parry et al. [50] | Durban, South Africa. A number of locations (i.e. streets in residential and industrial areas, and hotspots where drug users are known to frequent, such as shelters and community-based organizations) | Pre-post intervention study, formal evaluation to test whether a community-level intervention aimed at alcohol and other drugs (AOD) users has an impact on risky AOD use and sexual risk behavior | Self-reported alcohol and/or drug users ages ≥ 16 | Brief, peer-delivered, risk reduction outreach intervention to reduce AOD use and HIV risky behaviors |

| Peltzer et al. [84] | Forty primary health care facilities in 3 districts in South Africa | RCT to assess the effectiveness of screening and brief intervention (SBI) for alcohol use disorders among TB patients in public primary care clinics. Intervention group received SBI and control group received treatment as usual in addition to an alcohol education leaflet | Harmful drinkers (AUDIT scores 7 and above for women and 8 and above for me) ages ≥ 18, currently in treatment for tuberculosis (primary care) |

Screening and brief intervention to reduce alcohol misuse delivered by a clinic lay-counsellor For early identification of alcohol problems in public primary care the AUDIT and for the brief intervention the WHO brief intervention package for hazardous and harmful drinking was used |

| Rotheram-Borus et al. [74] | 24 low-income urban neighborhoods bordering Cape Town, South Africa | RCT to investigate the effects of a community-based home visiting maternal health intervention by trained non-professional health workers (mentor mothers) |

Low income pregnant women Self-reported drinking during pregnancy |

Improve maternal health through a home visiting intervention focused on general maternal and child health, HIV/tuberculosis, alcohol use, and nutrition |

| Xiaolu et al. [89] | 18 local hospitals in Beichuan county, China | Cluster randomized study… to determine the prevalence of problem alcohol use among the patients from village hospitals and investigate whether a structured BI for those with identified alcohol problems was effective in reducing their alcohol consumption. Nine intervention hospitals and 9 control hospitals | Persons ages ≥ 18 scoring 7 or above on the AUDIT. Persons who have experienced a catastrophic event (i.e. earthquake) |

‘Brief Intervention for Substance Use: manual for use in primary care’ recommended by WHO in 2003 |

Italicized text are direct quotations extracted from the included studies

Table 4.

Descriptions of the interventions and main findings

| Reference | Intervention characteristics | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|

| Almeida do Carmo et al. [87] | Recovery Housing (RH) program consisting of accommodation in a drug-free environment and a range of structured interventions to address drug and alcohol misuse, including abstinence-oriented interventions such as multi-professional case management, monitoring of drug use, pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment (motivational interviewing, daily care assistance, social and interpersonal functioning, relapse prevention, mutual help). A collaboration between the state and private companies provides job opportunities and is monitored by a social worker. Residents are also given the opportunity to return to education. The approach to family reintegration is determined on a case-by-case basis after evaluation of family ties | The most common drug use history was use of alcohol and cocaine (72%), followed by alcohol use alone (16%). 51% completed treatment or were reinserted in society (formal jobs and return to the family… and 49% had a recurrence during their stay; of the latter, 47% followed treatment at a rehabilitation or psychiatric clinic, 23.5% continued with outpatient treatment, and 29.5% returned to their families and continued treatment elsewhere. Twenty-nine of the 34 cases of recurrence occurred in the first 45 days of residence in the RH, and five between 150 and 180 days of residence |

| Assanangkornchai et al. [86] | The WHO ASSIST-linked brief intervention—delivered (by a project worker) as per the 10-step WHO procedure including a Feedback Report Card and Self-Help Strategies Manual (part of ASSIST) used to discuss with the patient the meaning of the score and strategies for reducing or stopping their substance use. The focus of intervention was on the substance that resulted in the highest score on the ASSIST or that was of most concern to the participant. The average duration of the BI sessions was 8.8 min and 3.9 min for the control group | Significant reductions over time in the specific substance involvement scores (SSIS) and total substance involvement scores (TSIS) for both alcohol and other substance users in the BI and SA groups (non-significant between-group differences). There were similar patterns of reduction in both groups over time and between facility types. There was an earlier reduction of scores in the sub-district health centers than in the district hospitals and participants from sub-district health centers changed from moderate-risk to low-risk faster and in greater proportions than those from district hospitals. At the end of the study 53.3% and 53.4% of the baseline ‘moderate-risk’ users in the BI and SA groups, respectively, had become ‘low-risk’. Between-group comparisons revealed non-significant differences in changes in frequency of use for both alcohol and other substances at three and 6 month |

| Humeniuk et al. [71] | The Brief Intervention (BI) was designed to be relatively short and easily linked to the results of the 7-item ASSIST screening questionnaire score via the use of the ASSIST Feedback Report card comprised a major part of the BI. Participants also took the self-help guide developed as part of the ASSIST package. The intervention incorporated motivational interviewing techniques that have been found to reduce client resistance while facilitating behavior change. Each country developed their own culturally appropriate brief intervention based on these principles. Average ASSIST baseline screening required 7.9 min and the BI 13.8 min. Screening and BI was delivered by trained project staff (treated as clinic staff for the intervention to appear to be routine care) and (in Brazil) by clinicians and researchers | There was a significant reduction over time for the pooled sample regardless of group, and a significant group x time interaction effect in which the group receiving the BI at baseline (regardless of substance) had significantly lower mean total illicit substance involvement scores at follow-up than the control group. Participants receiving the BI in Australia, Brazil and India had significantly reduced total illicit substance involvement scores at follow-up compared with control participants. There were also significant differences in interaction effects between the countries. Intervention effects were greatest among Australian participants. India and Brazil had a strong BI effect for cannabis, as did Australia and Brazil for stimulants and India for opioids. Although none of the substance-specific interaction effects were significant for the United States, there were significant reductions in both the experimental and control groups at follow-up for all substances. In general it appeared that severity of use within the moderate-risk range (scores 4–26) did not influence the success of the BI |

| Kane et al. [70] |

CETA is a transdiagnostic mental health intervention developed for delivery by non-professionals in LMIC…based on research of common elements or transdiagnostic treatment approaches used in the USA… but with a focus on being appropriate for training and delivery by non-professionals in lower resource settings. CETA is based on evidence-based treatments for trauma, anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems. The main components of CETA in this trial include: psychoeducation and engagement, anxiety management, behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, exposure, danger assessment and planning, CBT for SU and relapse prevention and safety planning and violence prevention CBT for SU component delivered to all men and substance-abusing women: included motivational enhancement and goal setting (particularly those related to SU drivers), and teaching and practicing behavior change and avoidance |

The trial was completed in January of 2019 (no results published yet). Results (compared to treatment as usual) will include: change in severity of violence against women scale (SVAWS), change in WHO IPV measures, change in youth victimization scale, change in AUDIT scores, change in ASSIST scores, change in CES-D scores (depression), change in Harvard Trauma Questionnaire scores (PTSD), change in child PTSD symptom scale scores, change in aggression scale, change in GEMS score (gender norms), change in Index of Psychological Abuse (psychological violence), change in hair sample cortisol biomarker Modifications to the protocol after first weeks of implementation: CETA delivery was changed to individual delivery instead of through group settings due to challenges in maintaining attendance to group sessions. This also led to an increase in the sample size to 248 families. |

| Lancaster et al. [76], data also extracted from sister article Miller et al. [77] | Index participants in the standard of care group received referrals to existing HIV and MAT clinics where they were given primarily methadone; a standardized harm-reduction package… and the WHO package of care for PWID… Intervention group received the standard harm-reduction package plus the following interventions: systems navigation to facilitate engagement, retention, and adherence in HIV care and MAT, and to negotiate the logistics and… costs of any required laboratory testing (e.g., tuberculosis testing) and transportation; psychosocial counselling by use of motivational interviewing, problem solving, skills building, and goal setting to facilitate initiation of ART and MAT, and if started, medication adherence; and ART initiation. The primary goal for systems navigation was to address individual-level or systems-level barriers to ART and MAT enrolment… A minimum of two psychosocial counselling sessions (Lasting 16–60 min) focused on ART and MAT adherence… tailored to the participant’s needs. Injection partners in both groups received a standardized harm-reduction package with referral for MAT | Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline were similar across the intervention and standard of care groups (mostly male, median age of 35). 402 (80%) index participants reported being ART naive at baseline. Only 109 (22%) index participants reported current MAT use at enrolment. Group distributions across sites were, on average, 125 to the standard of care group and 42 to intervention group. Findings showed that the intervention was feasible (80% retention at 52 weeks), with good intervention uptake, and led to increased ART use, MAT use, and viral suppression. In Vietnam and Ukraine, the intervention effect was positive for self-reported ART initiation, viral suppression, self-reported MAT initiation, and mortality, whereas in Indonesia the effect of the intervention appeared to be smaller. MAT uptake was lower than for ART but still significantly higher among intervention participants. In Vietnam, 42 (86%) of 49 index participants completed two psychosocial counselling encounters within 4 weeks compared with 30 (64%) of 47 participants in Ukraine and 15 (50%) of 30 participants in Indonesia. More counselling sessions were done with a support person present at the Vietnam and Ukraine |

| L’Engle et al. [75] | Six (approximately 20 min long) counselling sessions that took place monthly for 6 months. Nurse counsellors were trained in motivational interviewing techniques and provided the intervention in one-on-one sessions. Intervention contained elements from stages of change and social cognitive health behavior change theories and motivational interviewing. Specific (example) goals included: identification and discussion of risks and consequences from drinking, soliciting participants’ commitment to reduce drinking, identifying the goal of reduced drinking or abstinence, developing a habit-breaking plan, discussing high-risk situations and coping strategies, and providing feedback and encouragement | Nearly 75% of participants completed all 5 post-enrolment counselling sessions: 292 alcohol intervention participants (71.4%) and 296 nutrition control participants (72.5%). More participants in the intervention group than in the control group reported reduced drinking in the last 30 days at 6-month and 12-month follow-up visits (including frequency of drinking alcohol, overall binge drinking, binge drinking with paying clients, and binge drinking with non-paying partners—all statistically significant). Women in the intervention group had less than one third of the odds of reporting higher levels of drinking than women in the control group. No between-group differences on laboratory-confirmed STIs including HIV were detected. The odds of self-reported sexual violence from clients was significantly lower among intervention than control participants at both 6 and 12 months |

| Nadkarni et al. [82] |

Motivational Interviewing (MI) techniques were used across all the sessions to help patients develop and maintain their motivation to change. Several intervention manuals were identified in consultation with experts as potential starting points for the development of the CAP manual. CAP was delivered in 3 phases by trained non-professionals: Phase 1: Problem identification with the counsellor using assessments and personalized feedback. Generating a change and action plan that summarized the patient’s drinking-related problems and behaviors, and what steps he would take to achieve his behavior-change goals Phase 2: Helping the patient develop thinking and behavioral skills and techniques (e.g. drink refusal among others) Phase 3: Learning to manage potential or actual relapses using these thinking and behavioral skills and techniques CAP was delivered in 1 to 4 sessions at the patient’s home or the PHC |

Twenty-seven men were assigned to CAP and 26 to EUC. Forty-seven (88.7%) participants completed the outcome assessment and there were no statistically significant baseline characteristic differences between the groups (education, age, occupation, marital status, and AUDIT score). The amount of alcohol consumed in the past 2 weeks, mean AUDIT score, and alcohol-related problems were all lower in the CAP arm compared to the EUC arm, but the between-group adjusted mean differences were not statistically significant. There were nonsignificant reductions in outcomes in participants who completed treatment compared with those who dropped out with regard to mean AUDIT, … mean alcohol consumed in past 2 weeks, and mean SIP (Short Inventory of Problems, a 15-item questionnaire that measures physical, social, intrapersonal, impulsive, and interpersonal consequences of alcohol consumption) score. A number of key barriers were encountered and strategies were modified to address these (see Table 5) |

| Nadkarni et al. [73] | The CAP intervention was the same one as the one mentioned above and was delivered by 11 of the same lay-counsellors of the trial for harmful drinkers [73]. Referral to the local secondary or tertiary care de-addiction center for medically assisted detoxification consisted of informing the participants about the need for detoxification, providing them with details about de-addiction centers and suggesting that they attend (delivered in out-and in-patient settings in two district hospitals and one tertiary care psychiatry teaching institute, and private sectors) |

A total of 66 participants were randomized to EUC and 69 to CAP plus EUC. There was no significant difference between the arms for (a) proportion with remission at 3 months and 12 months; (b) proportion of participants reporting no alcohol consumption in the past 14 days at 3 months and 12 months; and (c) consumption among those who reported any drinking in this period at 3 months and 12 months. At 3 months, greater expectation of usefulness of counselling was associated with dropout from the study; and at 12 months, older age and greater readiness to change was associated with dropout from the study (that said, 89.6% of participants were retained at 3 months and 83% at 12 months). The mean number of sessions completed was 2.4 (SD = 1.2) and the mean session duration was 45.9 min (SD 9.6). Fifty-eight percent of participants achieved a planned discharge There was a 20% chance of CAP being cost-effective at the willingness-to-pay threshold of $415. However, from a societal perspective, there was a 53% chance of CAP being cost-effective |

| Noknoy et al. [72] | Motivational Enhancement Therapy delivered by trained primary care nurses; a brief intervention using the Project MATCH MET protocol (Miller et al. 1992). The intervention was composed of three scheduled sessions, on Day 1, at 2 weeks and at 6 weeks lasting approximately 15 min. Different techniques were used depending on the stage of behavior change of the patient (i.e. pre-contemplation, contemplation, determination, action, and maintenance), such as feedback, self-motivational statements, resolving ambivalence, readiness to change assessments, personalized action plans, goal setting, and relapse prevention | Self-reported drinks per drinking day, frequency of daily and weekly hazardous drinking and of binge drinking sessions were reduced in the intervention group more than the control group (P < 0.05 in 9/10 outcomes assessed) at 3 and 6 months. The groups did not differ at 3 or 6 months on self-reported frequency of being drunk. The incidence of alcohol-related consequences in the 6-month period was low in both groups. GGT (a biological marker available for evaluation of the severity of current drinking) levels were higher in both the intervention and control groups at 6-month follow-up than at baseline. However, the mean GGT level… in the intervention group was lower than… in the control group to a statistically significant degree (P= 0.038) |

| Pan et al. [88] | The participants in the CBT group received individual CBT weekly and group CBT monthly in addition to the standard care of MMT treatment for 26 weeks. The CBT was delivered by psychotherapists experienced in providing counselling or psychotherapy services for patients with SUDs and mental health disorders using an adapted intervention manual. The first 6 weeks focused on building treatment relationships and enhance motivation for MMT by helping patients understand their physical, mental health, social function, legal, economic, family, and employment problems associated with their opiate use, and by promoting commitment to treatment through signed ‘treatment goals-agreements’. Weeks 7–14 focused on skills training and… management of triggers for opiate use, as well as developing an individualized treatment protocols and receiving progress feedback to further improve the course of treatment. Weeks 15–26 focused on managing psychological stress, building a balanced lifestyle, and maintaining abstinence |

Participants had a higher (yet non-significant) retention rate in the CBT group than the control group at week 26. The average proportion of opiate-negative urine samples in the CBT group was higher than that in the control group at week 12 (p = 0.02) and week 26 (p = 0.02). The average days stay in MMT and mean dosage (mg/day) of methadone did not differ significantly between two groups In total, 72.5% completed the follow-up interview at week 26 (92 were in the CBT group, 82 were in the control group). The addiction severity index (ASI) scores decreased significantly over time in both groups with non-significant between-group differences. Analyses… revealed that the CBT groups improved more on employment function at 26 weeks, and decreased more on stress level at both week 12 and week 26 compared with the control group |

| Papas et al. [83], data also extracted from Papas et al. [43] | Six weekly 90-minute group sessions conducted in Kiswahili by Kenyan, trained non-professionals. The intervention was culturally adapted to best suit local beliefs, drinking behaviors, communications, stigma, gender differences, and HIV-positive diagnosis (see Table 5) | There were 42 CBT and 33 usual care participants. Of those randomized to CBT, participants attended 93% of the 6 sessions offered. Results … showed that… reductions since baseline were significantly larger in the CBT condition compared to the usual care condition for both percentage of drinking days (PDD) and number of drinks per drinking day (DDD). Cohen’s d effect sizes of reductions since baseline compared between conditions at 30-days post-treatment were large and at the 90-day follow-up were moderate. More CBT than control participants reported abstinence at all follow-ups. During the treatment phase, CBT participants reported reducing alcohol use at a faster rate than control participants… During the follow-up phase, CBT participants maintained reductions while control participants continued to report gradual reductions over time. It is not known whether differences between conditions increased or decreased beyond 90 days due to the study design. Independent ratings of CBT integrity among paraprofessionals showed acceptable adherence and skill ratings |

| Parry et al. [50] | Face-to-face baseline questionnaire with participants by peer outreach workers, risk behaviors were recorded and a risk-reduction plan was developed with each drug user which consisted of intravenous drug use and non-intravenous drug use (IDU/NIDU)-related risks, sex-related risks and HIV testing. Thereafter, an intervention session was offered to the clients covering education about HIV, condom demonstration and the provision of referrals as needed. Twenty peer outreach workers were recruited, trained, and paid to deliver the intervention. At follow-up (varying timeframes), both the questionnaire and risk-reduction plan were discussed again to assess behavior change and revise risk-reduction plans. There was monthly and bi-annual monitoring of intervention practices… through observations and performance ratings by the project coordinators. Behavior change and benefits of the intervention were self-reported | There were only statistically significant reductions in alcohol use between time 1 and time 2. No significant differences were observed over time for cannabis, cocaine, heroin and Ecstasy use. There was also no significant change in the frequency of substance use. In total, 45.7% of drug users did not report any changes in the number of different substances used, 23.2% increased the number of different substances they used and 31.1% decreased the total number of different substances used over the follow-up period (non-significant). Following the intervention, drug users had significantly fewer sex partners but there were no significant differences with regard to frequency of sex or use of condoms… In total, 39.1% of the drug users did not report any changes in the number of different substances used during sex, 21.7% increased the number of different substances that they used during sex and 39.1% decreased the total number of different substances used during sex (only significant reductions in marijuana use during sex) |

| Peltzer et al. [84] | The intervention consisted of two sessions (approximately 20 min), the first immediately after alcohol screening and the second within a month thereafter… In the control condition the clinic lay counsellor provided an alcohol education leaflet… The goals for brief counselling were as follows: (1) To identify any alcohol-related problems mentioned in the interview, (2) To introduce the sensible drinking leaflet, emphasis the idea of sensible drinking limits, and make sure that patients realize that they are in the risk drinking category, (3) To provide feedback on the relationship between alcohol and TB treatment, (4) To work through the first 3 sections of a problem solving manual, (5) To describe drinking diary cards, ((6) To identify a helper, and (7) To plan a follow-up counselling session… The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model was used in the study to guide the alcohol reduction intervention. The IMB model proposes that information about alcohol misuse and methods of reducing and preventing harmful and/or hazardous drinking is a necessary precursor to risk reduction | 1196 were randomized into 20 control and 20 intervention clinics (n=455, n=741, respectively) … In 75% of the intervention sessions, the lay counsellors implemented at least 6 of the 7 requisite intervention steps… In addition, it was found that in 96% of the cases of brief intervention, only one session was conducted despite having scheduled a follow-up session, and in 4% of cases two sessions. There were significant reductions in AUDIT score… over time across treatment groups… however the intervention effect on the AUDIT score was statistically not significant. The intervention effect was also not significant for hazardous or harmful drinkers and alcohol dependent drinkers, alcohol dependent drinkers and heavy episodic drinking, while the control group effect was significant for hazardous drinkers… At 6-month follow-up the intervention group did not significantly differ to the control group in terms of TB treatment cure or completion rate |

| Rotheram-Borus et al. [74] |

Home visiting included prenatal and postnatal visits by community health workers (Mentor Mothers) focusing on general maternal and child health, HIV/tuberculosis, alcohol use, and nutrition The intervention involved mostly education and support covering key health topics: HIV/TB, prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV, alcohol, mental health, breastfeeding, and malnutrition. Moreover, the community health workers (CHWs) were trained to promote skills to facilitate behavior change: goal setting, problem solving, relaxation, assertiveness, and shaping. On average, CHWs made six antenatal visits, five postnatal visits between birth and 2 months post 18 months old. After 18 months, visits only occurred once every birth, and 1.4 visits/month until the children were 6 months. Sessions lasted 31 min each on average |

Intervention membership was not significantly associated with any baseline variables except for an unexpected significant association with the intervention mothers reporting more depression… Having used alcohol during pregnancy was most associated with IPV at baseline and again at 36 months, as well as continued alcohol use at 18 and 36 months. Depression at baseline was most associated with concurrent partner violence, continued depression at 18 months, and more partner violence and less positive emotional health at 36 months… Positive emotional health was predicted by less alcohol use, less depression and less IPV at 18 months, less depression at baseline, and by being in the intervention condition… The intervention reduced depression even though initially the mothers in this condition were more depressed than those in the control condition… There also were significant indirect effects of baseline variables on the 36-month outcome variables… In addition to its direct effect, alcohol during pregnancy had an indirect effect on alcohol use at 36 months. Although the intervention reduced alcohol use in pregnancy, drinking resumed post birth |

| Xiaolu et al. [89] | BI used motivational interviewing techniques and incorporated FRAMES (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy and Self-efficacy) skills. The intervention lasts 15–30 min and is based on their alcohol use scores from the AUDIT. This approach is targeted toward non-dependent drinkers whose drinking may still be harmful. Intervention was delivered by 60 village hospital staff who were trained in the technique | Among the 239 problem drinkers, 47 (19.7%) had high risk drinking (AUDIT scores between 7 and 15), and 192 (80.3%) had harmful drinking (AUDIT were above 15). At follow-up assessment, compared with the control group, BI group demonstrated significant reductions in AUDIT… and self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) scores… and increased in substance abuse knowledge scale (SAKS)… and general well-being schedule (GWS) scores… controlling for age, education and baseline disequilibrium measurements. Results from separate ANOVA tests showed that there was a time effect… on AUDIT and SAKS in the BI group. The control group showed increase in SAS and SDS scores, and reduction in GWS scores (all significant). Compared with the control group, BI group showed greater reduction on AUDIT and increased on SAKS after intervention. |

Italicized text are direct quotations extracted from the included studies

Table 5.

Contextual factors coded data

| Reference | Cultural adaptations made | Capacity building of non-professionals | Policy factors discussed | Resource factors discussed | Sociocultural factors discussed | Implementation barriers/facilitators discussed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeida do Carmo et al. [87] | N/A | N/A |

This program was a direct result of a government launched initiative in 2013 Virtually all RH residents were not working and therefore would not have the right to apply for the government benefit due to local laws |

N/A |

Most of the residents asked for help by seeking health professionals, not family members. Authors mention that family groups may be protective factors, but can also be an important risk factor for crack use, e.g., because of the shame and stigma that affects family relations The reason most frequently cited for relapses by subjects (89%) was the difficulty of establishing family ties and building a social support network |

N/A |

| Assanangkornchai et al. [86] | The Thai version of the ASSIST was used to screen patients attending outpatient clinics held at the health centers. As krathom (mitragynine speciosa, Kroth., a traditionally used plant with sedative properties) and krathom cocktail (a mixture of boiled krathom leaf juice and a cola drink with medicines, such as benzodiazepines, antihistamines and ‘cough syrup’) are substances commonly used in the area, they were included in the Thai ASSIST under the ‘other drugs’ category | N/A | During the study period, the Thai Government launched a new initiative… with the target of reducing the number of users by 400,000 in the first year… Strategies to achieve this included: screening for substance abuse in various settings; various forms of compulsory treatment; and relapse prevention programs. This initiative could have influenced outcomes |

Most previous similar studies have been carried out in developed countries. Authors claim to have demonstrated that similar studies can be completed in developing countries despite problems in funding, staffing and transport; skepticism; and competing priorities In general practice and emergency services… the difference between 8 and 4 min… can be the main factor that determines whether or not screening is adopted as a routine procedure |

N/A | N/A |

| Humeniuk et al. [71] | Each country developed their own culturally appropriate brief intervention (no examples given) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kane et al. [70] | N/A | A 10-day in-person CETA training was conducted by study authors, followed by weekly small group meetings in which lay counsellors practiced the treatment elements with a local supervisor (before providing CETA to clients). Sixty-three lay counsellors (20 male, 43 female) and seven supervisors were trained in 2016. Supervisors completed one pilot treatment group to strengthen their CETA knowledge and skills and are periodically monitored. Weekly meetings are… held between each local supervisor and a CETA trainer. | N/A | N/A | N/A | After the first few weeks of intervention delivery, multiple participants were missing group sessions due to logistical challenges (e.g. work, funerals), which necessitated CETA providers to conduct separate individual sessions for participants that were absent. It became challenging for providers to keep up with the many in-between group sessions they had to conduct, and then also had to repeat material in groups if an individual missed and was not available in-between group sessions. Participants also indicated frustration in that they did want to participate but there was no flexibility for tardiness (in Zambia, this may be defined as an hour or more late) or work/family scheduling within groups. The challenges were substantial enough that the authors would not recommend group CETA in Lusaka, Zambia (urban area), even if it was found to be clinically effective. Therefore, they modified CETA to be individually delivered |

| Lancaster et al. [76], data also extracted from sister article Miller et al. [77] | N/A |

Trained outreach workers who were knowledgeable about community dynamics, including geographic areas, settings and organizations frequented by PWID, were selected to do the recruitment. Outreach workers were trained on basic methods of rapid assessment procedures to target areas of high drug use Note: counsellors in this study did have previous counselling experience. |

Local government restrictions on MAT access, such as low numbers of MAT clinics (Indonesia, Ukraine) and substantial travel distance (Vietnam), often complicated MAT initiation and retention In all three countries, the number of available MAT clinics is increasing due to changes in health policy, consequently, uptake of MAT services among the enrolled cohort may have increased throughout study follow-up. |

The role of systems navigator can be fulfilled by peers, social workers, counsellors, or clinicians—the key feature is that navigators understand the local health-care system and are able to facilitate entry and retention in care. The role did not require a high level of education—some counsellors in Ukraine and Indonesia did not have bachelor’s degrees. The roles of counsellor and systems navigator are conceptually distinct, but in all three sites, the same people served both roles, reducing the number of personnel necessary to implement the intervention |

For PWID in Vietnam, low levels of education may serve as a barrier for HIV and substance use treatment… the limited number of females in Indonesia and Vietnam accurately reflects the population of PWID in these countries based on culture and historic precedence. Female PWID often face more stigma and discrimination than their male PWID, which can be an additional barrier for engaging in HIV and substance use treatment. Treatment as prevention interventions, as well as substance use treatment, should address vary education levels and integrate female tailored approaches, where appropriate Injection network size likely reflects the social norms related to injection behavior in each area… (dense networks are associated with injection practices that increase the risk for HIV transmission)… The larger networks in Ukraine may arise because of the uncertainty of the drug sources and the culture of home-made drug preparation |

N/A |

| L’Engle et al. [75] | To ensure cultural relevance for FSW in Kenya, focus groups to inform intervention adaptation were held with FSW. Intervention adaptations included incorporating a ladder image to assess motivation and readiness to change because the original ruler image was not understood by less literate FSW and development of visuals depicting real-life situations of FSW such as fighting while intoxicated and not drinking while pregnant. Focus group participants also were asked about drinking patterns of FSW and for suggestions they had to reduce risky drinking before engaging in sexual activity; these ideas were incorporated into the intervention visuals and mentioned by counsellors as examples of methods FSW could use to reduce their drinking | Nurse counsellors were trained in motivational interviewing techniques and provided the intervention in one-on-one sessions lasting 20 min on average. Quality assurance of intervention delivery was provided monthly by an alcohol intervention expert through direct observation of counselling sessions, meeting with the nurse counsellors and presentation of cases, and review of data, assessment, and plan notes. | N/A | N/A | N/A | Authors found that the AUDIT was not effective enough at detecting drinking behavior changes over time. For example, some items referred to lifetime experiences and thus limited the ability to measure change in alcohol use or could not be easily or consistently answered by participants who had stopped drinking during the study period. Therefore, before unblinding, these end points were replaced with items from the behavioral interview asking about drinking behavior over the last 30 days that were answered by all participants regardless of current drinking status |

| Nadkarni et al. [82] |

CAP is entirely a culturally adapted intervention which was developed by (i) identifying potential treatment strategies; (ii) developing a theoretical framework for the treatment; and (iii) evaluating the acceptability, feasibility, and impact of the treatment. Further, data from a case series were used to inform several adaptations to enhance the acceptability of CAP to the recipients and feasibility of delivery by lay counsellors of the treatment. Four previously published intervention manuals were evaluated by assessing the adequacy of coverage of selected strategies, their suitability for use by lay counsellors, and the extent of adaptations needed for the local context CAP employs comprehensive and pictorially dominated psychoeducational materials to engage patients in the treatment since the vast majority of patients with harmful drinking in primary care are not specifically seeking help for their drinking problem and many patients have limited literacy. |

128 applicant non-professionals were selected for interview, which involved a structured questionnaire, a brief role play to test for skills such as empathy and questions to evaluate willingness to be part of a team, communication, and interpersonal skills. Following the interview, 31 candidates were invited for and completed the training. Of these, 19 completed the internship and delivered CAP under supervision. During the internship, the lay counsellors delivered CAP to patients in PHC and were supervised in groups by experts drawn from the group of local mental health professionals. CAP was iteratively revised based on observations made continuously through a case series. (See Patel et al., 2014; Singla et al., 2014 for further details) | N/A |

It was challenging for lay counsellors to achieve the standards of competence to deliver MI The main strength of this study is the structured methodology used to address the challenges inherent to the development, evaluation, and implementation of psychosocial interventions in low resource and culturally diverse contexts, which in turn has led to an intervention which is acceptable to various stakeholders, feasible to deliver, and hence has greater chances of being effective and scalable. If the resulting intervention is found to be cost-effective, then this has major implications for alcohol treatments in low resource settings |

Treatment engagement was hindered as primary care attenders rarely seek health care for their harmful drinking, and patients and family members are not accustomed to receiving “talking treatments” and express a desire for medications to treat the drinking problem; MI stance was not an acceptable approach in a setting where patients expect prescriptive advice from health professionals; Although CAP emphasized family involvement, family members sometimes saw counselling as a “waste of time” or patients were unwilling to involve family members | A third of the patients screening positive for harmful drinking were alcohol dependent. Patients often did not have time for the first session (45 to 60 min) after screening positive for harmful drinking. Dropout rates were high due to practical barriers such as lack of time to attend counselling because of work commitments and inability to travel to the PHC for financial reasons. |

| Nadkarni et al. [73] | See above | See above | N/A | N/A | The low prevalence rate of alcohol dependence in the study might be the result of the stigma associated with alcohol dependence which hinders help-seeking and could promote socially desirable responses to the screening and outcome tools | Alcohol dependence (AD) may require a more intensive psychosocial treatment, and a brief treatment such as the CAP might not be sufficient to deal with the complex cognitive and behavioral processes associated with AD |

| Noknoy et al. [72] | N/A | Nurses had been trained during a single 6-h session, which included an introduction to the research project, lecture and practice exercises to assess the severity of alcohol problems, the effect of alcohol on the patient’s health and the effect of alcohol on the family and society | N/A | Motivational interviewing is complex, and extensive practice is required to reach advanced levels. The extent and nature of training provided in this study are clearly sub-optimal by current international standards | The overall increase in GGT levels at week 6 may be because baseline data were collected immediately after ‘Kao Pansaa’, a 3-month period of Buddhist retreat during which it is customary for people to avoid wrongdoing, including limiting their alcohol drinking. After this period, normal drinking patterns are usually resumed… the increased mean levels of GGT are in contrast to the reduced alcohol consumption that was self-reported… this suggests that the use of self-reported data is still liable to social desirability bias. Any such problem may be exacerbated in Thailand where there is a cultural desire to please |

Fidelity to motivational interviewing was not assessed, so it is unknown to what extent the intervention—as delivered—represents an optimal and valid test of that particular type of brief intervention Because of the small number of women in the study, the effect of gender on outcomes could not be determined. |

| Pan et al. [88] | Translation of measurement tools/questionnaires to Chinese | Counsellors received training for the study in a 3-day didactic and interactive seminar. The competence of CBT counselling was rated with the validated rating system after training | N/A | N/A | N/A |

The frequency of collecting urine samples (once every 2 weeks) may not be sufficient to detect all likely incidents of drug use More time may be needed for MMT patients to incorporate the skills learned in CBT and to make the requisite changes from cognition to behaviors, especially with regard to negative attitude The protocol of CBT may need to be revised and adapted in the future to address specific characteristics and factors for improving treatment retention for MMT |

| Papas et al. [83], data also extracted from Papas et al. [43] |