Abstract

Human influenza virus pandemics constitute a major global public health issue. Although studies on autopsy specimens from the recent pandemic by the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus have revealed a broad spectrum of pathologic findings, direct electron microscopic studies of the lung tissue from influenza fatalities are few. In this study, we examined five well-preserved pulmonary necropsy specimens from fatal cases of laboratory-confirmed pH1N1 from India. The novel observations in comparison with earlier reports included direct imaging of influenza virus budding within dilated cisternae of pneumocytes, cell-free virus emerging from the cell membrane of a pneumocyte in the alveolar lumen, presence of polymorphonuclear cells with red blood cells as inflammatory exudates close to hyaline membranes and extensive cytoplasmic degeneration of epithelial cells of the alveolar lining. These observations are in consistent with the earlier findings and emphasize the possible role of this virus directly infecting cells of the lower respiratory tract as a key event in the rapid pathogenesis of pH1N1 disease process.

Keywords: pandemic influenza virus 2009, electron microscopy, necropsy, lung

The origin of a novel and initially untypable human influenza A virus in the spring of 2009 from California and Mexico rapidly unfolded into the dramatic and probably the fastest evolving human influenza pandemic with a virus of swine origin [1,2]. Approximately a year later, numerous studies have examined various aspects of this pandemic ranging from clinico-epidemiologic features to molecular genetic analysis of virus strains globally [3]. In a true international spirit of scientific collaboration, shared platforms were developed for researchers to access genetic data, published records and other material that would help an unified international approach to contain or rather blunt the edge of the pandemic's severity [4,5]. Potential animal models were explored for both understanding disease pathogenesis and testing antiviral prophylactic agents including vaccines [6–9], and vaccines are now commercially available. Autopsies and histopathologic characterization of pulmonary and other tissues in fatal cases of pH1N1 2009 virus were carried out in order to attempt to profile the pathologic basis of this pandemic virus in comparison with the earlier pandemics [10–14]. However, the spectrum of pathologic abnormalities did not significantly differ from what had been reported from earlier influenza pandemics of the past 120 years [15].

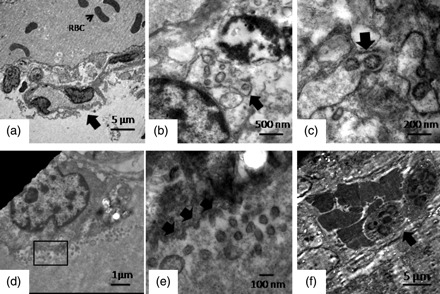

In India, the first cases of pH1N1 were detected in May 2009 and early data on confirmed cases and fatalities showed relatively lesser severity of the pandemic with the reported ‘Spanish flu’ but more severe than other pandemics of the century [16]. Genetic analysis of the virus isolates showed them to group with the globally circulating H1N1pdm clade 7 [17]. As a part of the routine investigation process, necropsy samples from fatal cases of acute respiratory illness during this phase were referred to the National Institute of Virology, Pune, which is the national Influenza Center and WHO Referral Center for H5N1. The lung tissue from five such cases (where the tissue preservation was good) with confirmed laboratory diagnosis of pH1N1 [18] were examined by transmission electron microscopy along with conventional histopathology techniques. There were two males and three females with an average age range of 24.3 years, the youngest being a three-and-a-half-year-old pediatric case. None of the patients had any detectable pre-existing pulmonary or other high-risk conditions and all developed acute respiratory distress and died within 5–10 days of admission to a tertiary care center. Briefly, bits of necropsied lung tissue were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, and embedded in epoxy resin blocks as described earlier [19]. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate, contrasted with Reynolds lead citrate and examined under 80 keV operating voltage in a transmission electron microscope (TEM; Tecnai 12 Biotwin, FEI Co., the Netherlands). While light microscopy examination showed histopathological changes similar to those reported earlier, TEM observations showed several novel features. The most interesting observation from TEM imaging was the direct visualization of the influenza virus particles associated with type II alveolar pneumocytes (Fig. 1). The virus particles, morphologically typical of Orthomyxoviridae, 80–100 nm and round-shaped were seen budding within the Golgi complex (Fig. 1b and c) and budding from the cell membrane (Fig. 1d and e). These observations are in consistent with a few earlier electron microscopic reports on imaging pH1N1 virus in lung [10,13,20] but novel in the sense that we could observe the virus budding within dilated cytoplasmic cisternae (Fig. 1b and c) not reported previously.

Fig. 1.

Ultrastructural changes in lung from fatal pH1N1 2009 cases. The panel shows major representative features from five fatal pH1N1cases. (a) A low-power image showing a key ultrastructural feature of alveolar basement membrane injury. The arrow indicates desquamating epithelial cells with extensive cytoplasmic degeneration, and red blood cell is present in the lumen. (b, c) Budding influenza virus in dilated cytoplasmic cisternae. (d) A low-power image showing a type II pneumocyte shedding virus within the alveolar lumen. The red box marks a representative area that is magnified in (e). A magnified image of the rectangular area of interest is shown in (a). Arrows show the budding virus emerging from the cell membrane. Cell-free viruses are also seen in the field (f). A representative image showing hemorrhagic and inflammatory exudates within the alveolar lumen. The arrow indicates the polymorphonuclear cells (magnification bars are embedded in each micrograph).

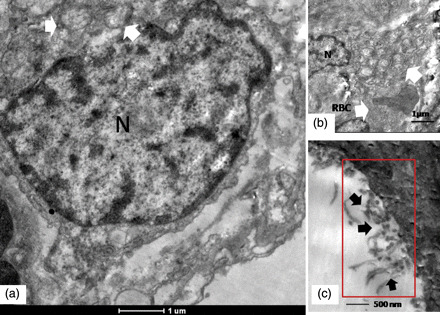

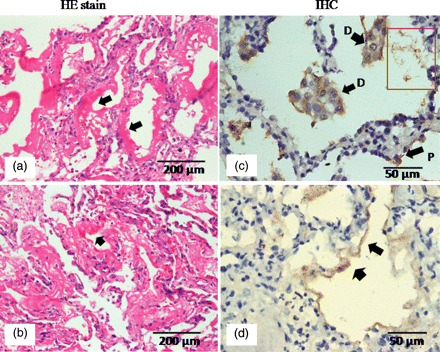

Moreover, another very interesting ultrastructural observation was the type of desquamation of the epithelial cells of the alveolar lining that showed a sloughing necrosis with extensive cytoplasmic degeneration and erosion of the basement membrane (Fig. 1a). The alveolar lumen also showed evidence of hemorrhage with abundant red blood cells (Fig. 1a), a very consistent observation that was seen in all the cases. Evidence of hemorrhagic necrosis along with polymorphonuclear infiltration was also prominent and seen in three of five cases (Fig. 1f). Typical ultrastructural features of Type II pneumocytes and extracellular forms of replicating virus were also observed in some cases (Fig. 2). Presence of viral antigen was detected by immunohistochemical staining in light microscopy (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Ultrastructural features of a representative type II pneumocyte in lung biopsy of a fatal pH1N1 2009 case. (a) Arrows indicate typical ultrastructural features of a type II pneumocyte in the form of multi-lamellate bodies. N designates the nucleus. Perinuclear degenerative changes are seen in the cell (refer text for description). (b) Multi-lamellated vesicular bodies typical of type II alveolar pneumocytes are shown by arrows. The field also shows a red blood cell from the hemorrhagic exudates (arrows). (c) Cell-free filamentous forms of the virus. Magnification bars are embedded into the micrographs.

Fig. 3.

Representative light micrographs showing pathology of DAD. (a, b) Hematoxylin–eosin-stained sections showing typical hyaline membrane formation in two different cases. (c) Immunohistochemical localization of H1N1 antigens in desquamated epithelial cells (D) within alveolar lumen are shown by arrows. P shows an infected pneumocyte. (d) Positive staining for viral antigens in hyaline membrane.

This report presents the ultrastructural findings from five well-preserved and promptly processed pulmonary necropsy samples from laboratory-confirmed fatal cases of pH1N1 2009 (see Fig. 2). Our findings are in consistent with the earlier electron microscopy studies that had identified extracellular virus particles in lung tissue sections from fatal pH1N1 2009 cases, but we could also directly image the virus replicating within dilated cisternal structures of pulmonary pneumocytes. We must admit that although it is extremely difficult to find infected cells in direct clinical specimens, we perhaps had a combination of proper fixation, probably high viremic load in the pulmonary tissue and analysis of many tissue sections that gave us this brief window to view the rare infected cells directly. The role of endoplasmic reticulum in influenza virus maturation has been shown to play a crucial role [21], and cisternal dilatations of the ER has also been implicated as key ultrastructural cytopathology in target cells [22]. Moreover, in consistent with earlier reports, we could also image a large number of cell-free virus shedding into the alveolar lumen from an infected pneumocyte, possibly reflecting a luminal shedding process in consistent with earlier observations [13,20]. However, detection of these infected cells was rare and was seen in only two cases.

In consistent with the earlier pathologic studies from previous influenza pandemics and seasonal outbreaks, diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), as a result of direct injury to the lower respiratory tract, was the major finding in fatal cases of pH1N1 2009 [10–15] but the pathobiology of this process remains incompletely understood (see Fig. 3). Several studies have suggested that possible presence of high-affinity receptors for the virus in lower respiratory tract may be a key trigger [23–25]. The electron micrograph in Fig. 1a is a representative image that probably shows the ultrastructural changes associated with DAD. The basal epithelial cells were also necrotized and sloughed off with hemorrhagic exudates in the alveolar lumen. The evidence of pathologic immune infiltrates including red blood cells and ploymorphonuclear cells (Fig. 1f) was in consistent with earlier reports of alveolar hemorrhage and inflammatory exudation within alveoli of fatal influenza cases [26,27]. High-power scans in several such areas showed virally infected underlying pneumocytes.

In summary, our ultrastructural findings in the lung of five fatal cases of pH1N1 2009 shows DAD as a predominant pathologic process in the lower respiratory tract – directly reflecting alveolar injury both by direct virus replication in pneumocytes and associated degeneration of the alveolar structures – probably by concurrent host immune processes. These observations are in consistent with other light and electron microscopic findings in lung tissue of fatal pH1N1 2009 cases. Further studies with electron microscopy immunolabeling for both viral and host markers in cryosubstituted pulmonary tissues sampled from various sites of pulmonary lesions in fresh autopsies has the potential to provide better understanding of the pathogenesis of this pandemic virus in conjunction with other studies in a holistic way.

Funding

This work was funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research, Government of India.

Authors' note

Although the present study was a part of pandemic disease investigation process, institutional ethical and IBSC approvals were obtained. The fatal cases have been treated as anonymous.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical expertise provided by Mr Rajendra Kolhapure, Mr Laxman Hungun and pathologist colleagues at the BJMC.

References

- 1.Dawood F S, Jain S, Finelli L, et al. Emergence of a novel swine origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2605–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uyeki T M. 2009 H1N1 virus transmission. New Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1004468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garten R J, Davis C T, Russell C A, et al. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A (H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science. 2009;325:197–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1176225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO guidelines for pharmacological management of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 and other influenza viruses. Geneva: World Health Organization; at http//www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/h1n1_guidelines_pharmaceutical.management.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FLUNET. http://gamapserver.who.int/GlobalAtlas/home.asp .

- 6.Itoh Y, Shinya K, Kiso M, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of new swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Nature. 2009;460:1021–1025. doi: 10.1038/nature08260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munster V J, de Wit E, van den Brand J M, et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of swine-origin A (H1N1) influenza virus in ferrets. Science. 2009;325:481–483. doi: 10.1126/science.1177127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sreta D, Kedkovid R, Tuamsang S, et al. Pathogenesis of swine influenza virus (Thai isolates) in weanling pigs: an experimental trial. Virol. J. 2009;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hessel A, Schewndinger M, Fritz D, Coulibaly S, Holzer G W, et al. A pandemic influenza H1N1 live vaccine based on modified vaccine Ankara is highly immunogenic and protects mice in active and passive immunizations. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maud T, Hjjar L A, Callegari G D, et al. Lung pathology in fatal novel human influenza A (H1N1) infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010;181:72–79. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1420OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soto-Abraham M V, Soriano-Rosas J, Diaz-Quinonez A, et al. Pathological changes associated with the 2009 H1N1 virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 361:2001–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0907171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill J R, Sheng Z M, Ely S F, et al. Pulmonary pathologic findings of fatal 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 viral infections. Arch. Pathol. Lab Med. 2010;134:235–243. doi: 10.5858/134.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shieh W-J, Blau D M, Denison A M, et al. 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) pathology and pathogenesis of 100 fatal cases in the United States. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;177:166–175. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaurner J, Paddock C D, Shieh W J, et al. Histopathological and immunohistochemical features of fatal influenza virus infection in children during 2003–2004 season. Clin. Inf. Dis. 2006;43:132–140. doi: 10.1086/505122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taubenberger J K, Morens D M. The pathology of influenza virus infection. Ann. Rev. Pathol. 2008;3:499–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mishra A C, Chadha M S, Choudhary M L, Potdar V A. Pandemic influenza (H1N1) 2009 is associated with severe disease in India. PLos ONE. 2010;5:e10540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potdar V A, Chadha M S, Jadhav S M, Mullick J, Cherian S S, Mishra A C. Genetic characterization of the influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus isolates from India. PLos ONE. 2010;5:e9693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CDC. Swine influenza A (H1N1) infection in two children – Southern California, March–April 2009. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2009;58:400–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bozolla J J, Russell L D. Electron Microscopy, Principles and Techniques for Biologists. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 1992. Specimen preparation for transmission electron microscopy; pp. 16–37. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakajima N, Hata S, Sato Y, et al. The first autopsy case of pandemic influenza (A/h1n1pdm) virus infection in Japan: detection of a high copy number of the virus in type II alveolar epithelial cells by pathological and virological examination. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;63:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang N, Glidden EJ, Murphy SR, Pearse BR, Hebert DN. The cotranslational maturation program for the type II membrane glycoprotein influenza neuraminidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:33826–33837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806897200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghadially F N. Ultrastructural Pathology of the Cell. UK: Butterworth & Co; 1978. Virus in endoplasmic reticulum. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeh E, Luo R F, Dyner L, et al. Preferential lower respiratory tract infection in swine-origin 2009 A (H1N1) influenza. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;50:391–394. doi: 10.1086/649875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Riel D, Munster V J, de Wit E, et al. Human and avian influenza viruses target different cells in the lower respiratory tract of humans and other mammals. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171:1215–1223. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi L, Kash J C, Dugan V G, et al. Role of sialic acid binding specificity of the 1918 influenza virus hemagglutinin protein in virulence and pathogenesis for mice. J. Virol. 2009;83:3754–3761. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02596-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christopher R, Gilbert D O, Kumar V, Baram M. Novel H1N1 influenza A viral infection complicated by alveolar hemorrhage. Resp. Care. 2010;55:623–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perrone L A, Plowden J K, Garcia-Sastre A, Katz J M, Tumpey T M. H5N1 and 1918 pandemic influenza virus infection results in early and excessive infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils in the lungs of mice. PLos Pathog. 2008;4:e1000115. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]