Abstract

Background

Breast cancer and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection are major health problems in the U.S. Despite these highly prevalent diseases, there is limited information on the effect of HCV infection among patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy and the potential challenges they face during treatment. Currently, there are no guidelines for chemotherapy administration in HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective case–control analysis on six patients with breast cancer with active HCV infection and 12 HCV‐negative matched controls who received chemotherapy between January 2000 and April 2015. We investigated dose delays, dose changes, hospitalization, hematologic reasons for dose delays, and variation in blood counts during chemotherapy from the patients’ medical records. Fisher's exact test was used for statistical comparison of the outcome variables between the two groups.

Results

When compared with the HCV‐negative patients, the HCV‐positive group was at a significantly higher risk of dose delays (100% vs. 33%, p value .013), dose changes (67% vs. 8%, p value .022), hospitalization during chemotherapy (83% vs. 25%, p value .043), and hematotoxicity related dose delays (83% vs. 8%, p value .003). HCV‐positive patients took a longer time to complete treatment than the HCV‐negative group.

Conclusion

Patients with HCV receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer are more likely to experience complications such as dose delays, dose modifications, and hospitalization. Future studies to confirm our findings and investigate on the effect of concurrent HCV and breast cancer treatment are warranted.

Implications for Practice

This study found that hepatitis C infection is associated with a greater risk of treatment delays and dose modifications in patients with breast cancer receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy. Hepatitis C–positive patients have a higher treatment burden with dose changes, hospitalizations, and longer treatment periods than noninfected patients. Further prospective investigations to confirm these findings are warranted in a larger patient population. Given that hepatitis C infection can be curable with direct‐acting antivirals, treatment of hepatitis C may alleviate treatment challenges during chemotherapy and improve survival for patients with breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Hepatitis C virus

Short abstract

Currently, there are no guidelines for chemotherapy administration in hepatitis C virus‐positive patients with breast cancer. This article addresses the knowledge gap, comparing breast cancer patients with and without concurrent hepatitis C virus to determine level of tolerance to treatment.

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a public health problem that affects millions of people worldwide [1]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the incidence rate of acute hepatitis C in the U.S. was higher in 2016 than in 2015 [2]. According to a recent CDC report on HCV, in 2016, a total of 2,967 cases of acute hepatitis C were reported to the CDC from 42 states across the U.S., representing an overall incidence rate of 1 case per 100,000 population [2]. From the 2013–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, Hofmeister et al. estimated that approximately 2.4 million people in the U.S. had active HCV infection [3]. In addition to its increasing prevalence, HCV is an oncogenic virus that is associated with several types of cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma, renal cancer, and prostate cancer [4]. In a retrospective study using the cancer registry at the Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Nyberg et al. showed that patients with HCV infection were 2.5 times more likely to have a cancer diagnosis than those without HCV, including liver cancer [4, 5]. Even when liver cancer was excluded, cancer risk in HCV‐positive patients was still almost two times higher [4, 5]. It is estimated that in patients with cancer, the prevalence of HCV is between 1.5% and 32% depending on geographic area and type of cancer studied [6].

Like HCV, breast cancer is common, affecting one in eight women in the U.S. [7, 8]. And breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death among women in the U.S. [7, 8]. Recent estimates find the incidence rate and mortality rate of breast cancer in U.S. women as 242,476 new cases and 41,523 deaths, respectively [7]. In spite of the overwhelming numbers reported, the incidence of breast cancer in women in the U.S. has decreased since 2000 and the death rates have been declining since 1989 [9]. This is largely due to increased awareness, screening techniques that offer early detection, and advancements in treatment [9]. Treatment for breast cancer (surgery, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, biological therapy, or radiation therapy), depends largely on the type and stage of the disease diagnosed [8]. Adjuvant chemotherapy has made a large contribution to the improved mortality rates in breast cancer over the past several decades.

HCV can affect chemotherapy administration in many ways. First, chemotherapy is often metabolized through the liver. As such, treating patients with liver disease and malignancy with hepatically cleared chemotherapy can be particularly challenging [10, 11]. Second, HCV can suppress and impair the bone marrow and hematopoiesis [12]. Previous reports have illustrated cases in which a concurrent infection has prolonged or increased the severity of chemotherapy‐related adverse events, causing dose reduction or forcing patients to discontinue life‐saving cancer treatment [13, 14]. Despite reports that concurrent HCV infection and cancer diagnosis increases the mortality rate of patients, little evidence exists to guide the management of HCV infection in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy.

The aim of the current study is to address this knowledge gap and determine whether patients with breast cancer with concurrent HCV infection undergoing chemotherapy have a lower tolerance to treatment and find it more difficult to complete the regimen when compared with their noninfected counterparts. To understand the difference in tolerance to chemotherapy, our primary objective was to compare dose modification, dose delay, and hospitalization due to adverse events during chemotherapy between HCV‐positive and HCV‐negative patients with breast cancer being treated with chemotherapy. Our secondary objective is to compare blood count (white blood cell count and absolute neutrophil count) between the two groups of patients during the chemotherapy cycles. Because HCV‐positive patients have impaired hepatic functions, we hypothesize that those patients will have increased dose delays, dose modifications, hospitalization, and hematologically associated dose changes during their treatment compared with their HCV‐negative counterparts.

Materials and Methods

Subject Selection

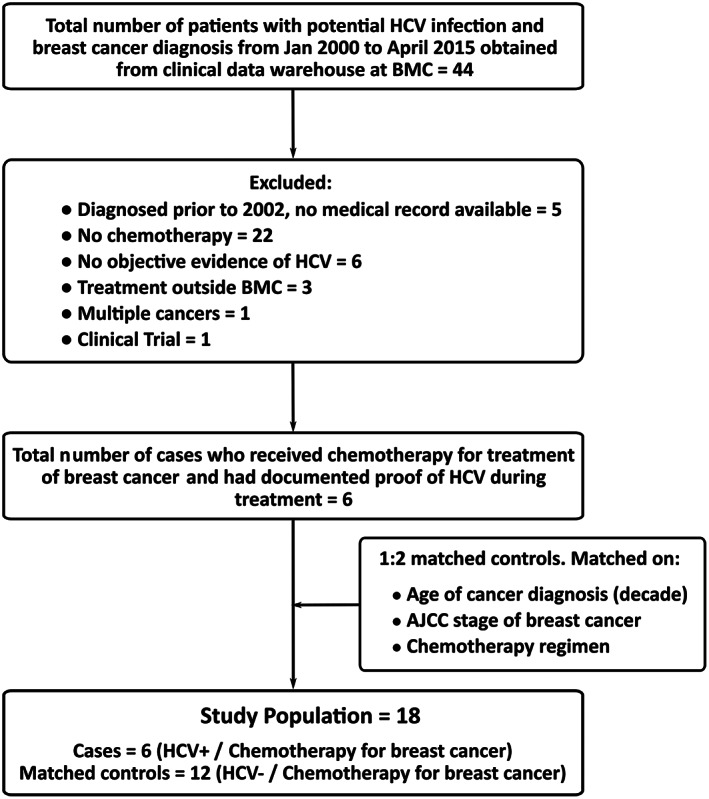

This is a retrospective chart review using data collected in the Boston Medical Center (BMC) cancer registry and in‐depth investigation of patient electronic medical records (EMRs). The BMC cancer registry clinical data warehouse provided a list of 44 potential HCV‐positive patients who were 18 years or older and were concurrently diagnosed and treated at BMC for breast cancer between January 2000 and April 2015. Medical records of these patients were then examined to identify those who received chemotherapy at BMC for their malignancy and had documented proof of an HCV infection during their treatment. We defined “documented proof” as a detectable viral load (viral load >615 IU/L) in the patient prior to their chemotherapy as measured using HCV RNA, quantitative, real‐time polymerase chain reaction. To eliminate confounding, we did not include patients diagnosed with multiple cancers. We also excluded participants who (a) did not get treatment at BMC as we could not access their medical record, (b) did not have any documented medical record of their treatment in the EMR (cases diagnosed prior to 2002), or (c) were treated as a part of clinical trials during their treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study population.

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BMC, Boston Medical Center; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Following the identification of the cases, we selected matched controls from the BMC cancer registry. Each patient was matched with two HCV‐negative controls. The patients were matched for (a) age (decade) of diagnosis, (b) stage of breast cancer, and (c) chemotherapy regimen (Doxorubicin/adriamycin, cyclophosphamide/cytoxan, followed by Paclitaxel/Taxol [ACT] or Docetaxel/Taxotere, cyclophosphamide/cytoxan [TC]).

This study was approved by the BMC Institutional Review Board (IRB; IRB Number H‐33957). Because the study involved a retrospective evaluation of patient records and was no more than minimal risk to the subjects, a waiver for the written informed consent was obtained from the IRB for this study.

Outcome Variables

We investigated whether patients had (a) a delay in their chemotherapy, (b) a dose change in their chemotherapy, (c) a hospitalization due to side effects related to chemotherapy toxicity, and (d) any hematologic reasons for delay in treatment. The outcome variables were determined for each patient from an in‐depth analysis of their medical records. A delay in chemotherapy is defined as an interruption in administration of chemotherapy due to any reason. A dose change in chemotherapy is defined as a change in either drug dose or drug type at any point during the treatment period. For hospitalization due to side effects related to chemotherapy toxicities, all hospitalization from day 1 cycle 1 chemotherapy until 7 days after last dose of chemotherapy was considered. Hematologic delay in treatment is defined as a delay in administration of chemotherapy due to low white blood cell (WBC) count or low absolute neutrophil count (ANC) as noted in the medical record as reason for withholding treatment.

We also investigated the variation in WBC and ANC in every patient during the chemotherapy cycles. These values were noted at four timepoints—before the first dose of chemotherapy, during the first nadir visit, before the second dose of chemotherapy, and before the last dose of chemotherapy. In addition to receiving chemotherapy, 10 of the 18 patients mentioned in this study also received peg‐filgrastim or equivalent. Of these 10 patients, 4 were cases and 6 were control. The number of doses of bone marrow stimulant any patient received was patient specific and was determined by the treating physician based on the condition of the patient.

Statistical Analysis

R version 3.4.0 was used for all statistical analyses. The mean ± SD, median, and range are reported for all continuous variables and counts and percentages for all categorical variables to characterize the study population. Given our small sample size, we used Fisher's exact test to compare categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests to compare continuous variables between the cases and controls. All statistical tests presented are two‐sided and p values <.05 are considered statistically significant.

Results

The hospital cancer registry clinical data warehouse provided a list of 44 potential HCV‐positive patients 18 years or older who were diagnosed and treated at BMC for breast cancer between January 2000 and April 2015. We identified six patients from this list who received chemotherapy for breast cancer at BMC and had documented proof of being HCV positive during their treatment (Fig. 1). We excluded 38 patients for the following reasons: diagnosis prior to 2002 and hence no record in the EMR (n = 5), no documented proof of HCV (n = 6), multiple cancer (n = 1), no chemotherapy (n = 22), treatment outside BMC (n = 3), and patient enrolled in clinical trials (n = 1). Each patient was matched for age (decade) of diagnosis, stage of breast cancer, and intended chemotherapy regimen with two controls who were HCV negative. These two groups were compared.

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. All the patients were female with the average age at breast cancer diagnosis being 52.9 ± 6.1 and 53.5 ± 8.0 years in the HCV‐positive and ‐negative groups, respectively. In the HCV‐positive group, four patients (67%) had estrogen receptor (ER)‐positive breast cancer, three patients (50%) had progesterone receptor (PR)‐positive breast cancer, and no one had human epidermal growth receptor 2 (HER2)‐positive breast cancer. In the control group, five patients (42%) had ER‐positive breast cancer, three patients (25%) had PR‐positive breast cancer, and no one had HER2‐positive breast cancer. All patients had invasive ductal carcinoma. In both groups, 17% of patients had stage I, IA, II, or IIB disease and 33% of patients had stage IIA disease. In both groups, the intended chemotherapy regimen was ACT for 83% of patients and TC for the remainder. In the HCV‐positive group, all patients were positive for HCV genotype Ia and only two (33%) also tested positive for genotype Ib. Only one of the six HCV‐positive patients received any prior treatment for their HCV infection. This patient received an 11‐month interferon treatment that ended almost 5 years before the cancer diagnosis. The patient responded to the treatment but did not have a sustained virologic release.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population

| Variables | Cases (n = 6) | Controls (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|

| (HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer) | (HCV‐negative patients with breast cancer) | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 52.9 (6.1) | 53.5 (8.0) |

| Sex, female | 6 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 4 (67) | 4 (33) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (17) | 0 |

| White | 0 | 4 (33) |

| Asian | 0 | 2 (17) |

| Declined | 1 (17) | 2 (17) |

| Tobacco use | ||

| Current | 2 (33) | 0 |

| Ex | 2 (33) | 5 (42) |

| Never | 2 (33) | 7 (58) |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Current | 2 (33) | 4 (33) |

| Ex | 3 (50) | 0 |

| Never | 1 (17) | 7 (58) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Substance use | ||

| Current | 0 | 0 |

| Ex | 4 (67) | 0 |

| Never | 2 (33) | 7 (58) |

| Unknown | 0 | 5 (42) |

| HCV | — | |

| Genotype | ||

| 1a | 6 (100) | |

| 1b | 2 (33) | |

| Treatment prior to chemotherapy | 1 (17) | |

| Stage of cancer | ||

| I | 1 (17) | 2 (17) |

| IA | 1 (17) | 2 (17) |

| II | 1 (17) | 2 (17) |

| IIA | 2 (33) | 4 (33) |

| IIB | 1 (17) | 2 (17) |

| Histology | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 6 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 0 | 0 |

| Immunohistochemistry | ||

| ER status | ||

| Positive | 4 (67) | 5 (42) |

| Negative | 2 (33) | 7 (58) |

| PR status | ||

| Positive | 3 (50) | 3 (25) |

| Negative | 3 (50) | 9 (75) |

| HER2 status | ||

| Positive | 0 | 0 |

| Negative | 6 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Intended chemotherapy regimen | ||

| ACT | 5 (83) | 10 (83) |

| TC | 1 (17) | 2 (17) |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: ACT, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, followed by Taxol; ER, estrogen receptor; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HER2, human epidermal growth receptor 2; PR, progesterone receptor; TC, Taxotere, cyclophosphamide.

In the HCV‐positive group, all the patients had a delay in drug administration, four patients (67%) had a dose change in chemotherapy, and five patients (83%) were hospitalized during treatment. The treatment of one patient in the HCV‐positive group was delayed four times owing to hematologic and treatment‐related side effects. This patient was hospitalized five times during her treatment cycle. Another patient in the HCV‐positive group had a change in the chemotherapy regimen after the first cycle of the TC regimen because of intolerance to treatment. This patient finally completed a CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil) chemotherapy regimen with two dose delay and one dose reduction during the five cycles. On the contrary, in the control group, only four patients (33%) had a delay in drug administration, one patient (8%) had a dose change in chemotherapy, and three patients (25%) were hospitalized during treatment. All patients in the HCV‐negative group could complete their intended chemotherapy regimen, and only one patient was hospitalized twice during her treatment. The results show that the HCV‐positive group is at a significantly higher risk of dose delays (p = .013), dose changes (p = .022), and hospitalization during chemotherapy (p = .043) than the HCV‐negative patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of primary outcome variables in the hepatitis C virus–positive (cases) and –negative (controls) patients with breast cancer

| Variables | Cases (n = 6) | Controls (n = 12) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose delay | 6 (100) | 4 (33) | .013 |

| Dose change | 4 (67) | 1 (8) | .022 |

| Hospitalization | 5 (83) | 3 (25) | .043 |

| Hematologic dose delay | 5 (83) | 1 (8) | .004 |

Values are n (%).

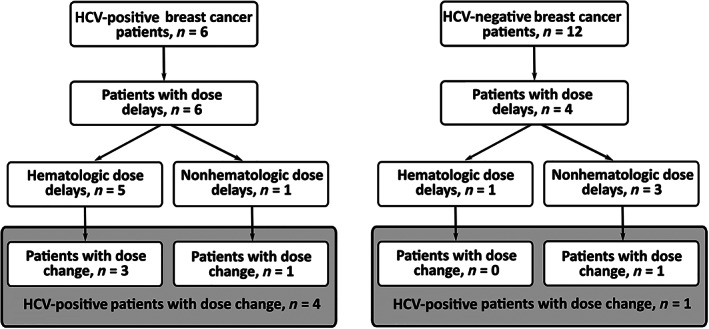

Among the patients with dose delays, four out of six (67% of HCV‐positive group) and one out of four (8% of HCV‐negative group) patients also had treatment changes. Because clinicians often have to delay or change the scheduled administration of chemotherapy as a result of drug‐related hematologic toxicities [24], we also compared the number of patients getting dose delays because of hematologic reasons. The dose delay was due to hematologic reasons for five patients (83%) in the HCV‐positive group and only one patient (8%) in the HCV‐negative group (Fig. 2). The one patient in the HCV‐positive group with nonhematologic dose delay had treatment interruptions owing to chemotherapy‐related side effects (weakness and hand‐foot syndrome). The three patients in the HCV‐negative group with nonhematologic dose delays had interruption to chemotherapy owing to treatment side effects (weakness, emesis, diarrhea, or skin lesions), and only one among them had a dose change (Fig. 2). Our results show that the risk of getting a dose delay as a result of hematologic factors was significantly higher in the HCV‐positive group than in the HCV‐negative group (p = .004; Table 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the number of HCV‐positive and HCV‐negative patients with hematologic dose delay and dose change.

Abbreviation: HCV, hepatitis C virus.

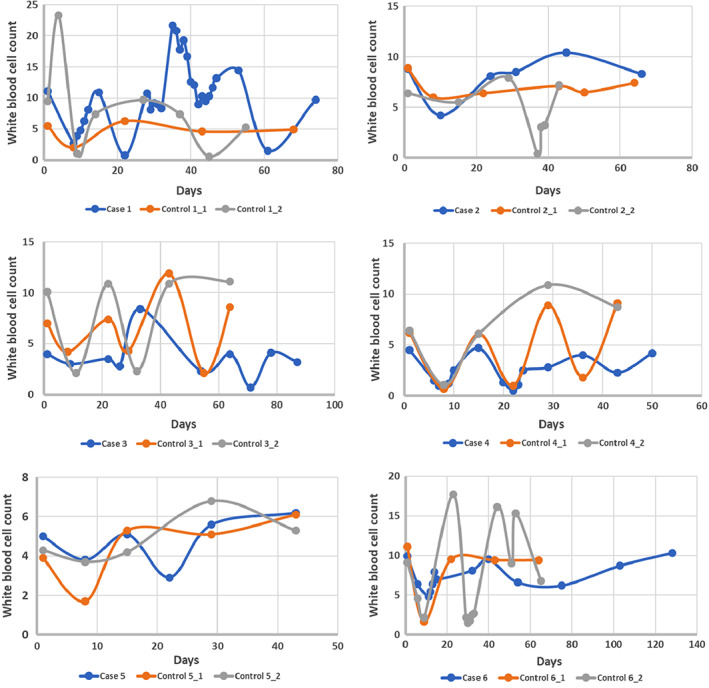

WBC and ANC were measured in all patients at four times during treatment (as outlined in Materials and Methods). The blood counts were calculated at two intervals—(a) between first chemotherapy cycle and nadir and (b) between nadir and second chemotherapy cycle. The variation in blood counts showed a similar trend in all patients. During the nadir visit (day 8 of chemotherapy), values of both WBC and ANC decreased in all patients followed by an increase during the second and last chemotherapy cycles (Fig. 3). There was no statistical difference between the decrease or increase in blood counts between the two groups for the two intervals, respectively. However, when we plotted the variation of WBC during the chemotherapy cycles for the HCV‐positive patients and their matched controls, we saw that the HCV‐positive group took a longer time to complete their treatment and for their blood counts to come back to the levels similar to when they started their treatment (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Variation of WBC count in six hepatitis C virus (HCV)‐positive patients with breast cancer and their corresponding HCV‐negative matched controls. The first five cases and their controls received ACT regimen for their treatment and the variation is plotted only during the AC cycles.

Abbreviation: WBC, white blood cell.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, and chronic HCV is a major health problem in the U.S. [2, 3, 7, 8]. Unfortunately, the clinical impact of HCV infection on patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy remains poorly understood. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first matched case–control study to better understand the complications in patients with breast cancer with HCV infection undergoing chemotherapy. We found that HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer have significantly lower tolerance to cytotoxic chemotherapy when compared with their HCV‐negative counterparts. A concurrent HCV infection put them at a significantly higher risk of dose delays, dose modifications, and hospitalization during chemotherapy when compared with their HCV‐negative counterparts.

In our cohort, we compared HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer with matched HCV‐negative patients and saw that the former have a low tolerance to chemotherapy and prolonged treatment duration. The duration of treatment increases because of treatment delays and hospitalization, which is significantly higher in the HCV‐positive group. The treatment delays are due to either hematotoxicity or exacerbation of prior conditions that prevent the patients from receiving chemotherapy on time. Unfortunately, treatment delays in breast cancer are associated with poorer survival. Therefore, measures should be taken to avoid or minimize any treatment delays.

Despite the fact that breast cancer affects a large number of women in the U.S., we have a limited understanding of how concurrent HCV infection may affect successful completion of adjuvant chemotherapy. Retrospective studies have shown that chemotherapy‐related adverse effects in HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer result in changes and delays in treatment or even total discontinuation of therapy [15, 16, 17]. Morrow et al. report that of the 36 HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer who received chemotherapy, 16 (44%) had either dose reduction or delays in their cancer treatment and 23 (64%) experienced grade 2 or greater adverse events including neutropenic fever, non‐neutropenic infection, and neuropathy [15]. Similarly, Miura et al. report that of the 10 HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer receiving cytotoxic agents and/or trastuzumab, 6 developed grade 4 neutropenia, 4 developed febrile neutropenia, and 3 had dose reduction [16]. In line with these observations, Talima et al. report that of the 44 HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer being treated with chemotherapy, only 30 (68.2%) could complete their treatment [17]. Fourteen patients (31.8%) failed to complete their treatment owing to hematologic side effects, liver toxicity, or both and were taken off chemotherapy, and 12 patients (27.2%) had dose reduction or dose delays. Twenty‐five out of 44 patients (56.8%) developed complications related to chemotherapy during treatment and 2 developed HCV reactivation, of whom 1 patient died as a result of fulminant hepatitis. As reported, adverse effects of chemotherapy on HCV‐infected individuals include hematologic side effects (neutropenia), neuropathy, fever, and liver toxicities. Others have concluded that HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer tolerate chemotherapy well [18, 19]. However, without a comparator group in these studies, it is difficult to conclusively say that HCV infection is either related or not related to the low tolerance to chemotherapy in these patients.

In contrast to these observations, D'Angelo et al. concluded that chemotherapy is well tolerated in HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer as only 4 out of 29 patients (13%) had treatment delays or adjustments [18]. Similarly, Shoji et al. reported that of the 52 HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer who received chemotherapy, only 8 (15%) had treatment delays, and they concluded that treatment delays were not prevalent in this group of patients [19]. However, like the earlier reports, they do not compare their results in noninfected patients with breast cancer. Liu et al., on the other hand, report that although the interruption in breast cancer chemotherapy was higher in 21 HCV‐positive patients treated, the difference was not statistically significant when compared with the 762 HCV‐negative patients [20]. Although the current literature has conflicting reports on the tolerance of chemotherapy in HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer, clinicians agree that a concurrent HCV infection on chemotherapy requires close monitoring for adverse events.

The only paper that compared the tolerance of chemotherapy in HCV‐positive and ‐negative breast cancer did not find any significant difference between the two groups when it came to treatment disruptions, even when such disruptions were higher in the HCV‐positive group [20]. However, in this paper, the authors did not use matched controls and did not take into account other confounders such as stage of the disease and chemotherapy regimen. Torres et al. have proposed an algorithm for treating HCV‐positive patients with hematologic malignancies; however, such treatment algorithms or guidelines are not available for other cancer types [21].

Our study emphasizes the concern that a chronic HCV infection may put a patient with breast cancer at a higher risk of treatment delay. Fortunately, chronic HCV is currently treatable with several direct‐acting antivirals (DAAs) that can target various HCV genotypes, stages of liver disease, and comorbidities [22]. These DAAs, which act by targeting the virus replication machinery, are generally well tolerated and can attain sustained virologic response rates greater than 90% [22, 23]. According to the treatment guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, all patients with chronic HCV infections should be treated with DAAs, except those who are expected to live less than 12 months even after they are treated for HCV or get a liver transplant [24]. The dose and type of drug given to a patient will depend on the prior treatments received and the genotype of the infection.

Given the current knowledge about breast cancer and HCV and the availability for treatment with DAAs, the question arises of whether HCV infection should be concurrently treated with a diagnosis of any cancer requiring myelosuppressive chemotherapy. This would be akin to the way human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is treated in patients with cancer. Although cancer clinical trials have typically excluded HIV‐positive patients, with the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy for patients with HIV, clinicians now concurrently treat HIV infection and cancer in patients [25, 26, 27]. The treatment is usually based on a plan formulated by the oncologist and infectious disease specialist keeping in mind the safety of the patient [25, 26]. Our results provide support to investigate whether HCV infection could be treated concurrently in patients with breast cancer on active treatment, similar to HIV, to give these people a better chance at tolerating their chemotherapy and surviving their cancer.

Our study has limitations. First and foremost, the small size of our study sample may be responsible for not capturing any difference in WBC and ANC in the two group of patients. In order to definitively answer this question, a more rigorous, prospective trial or large database would be better at confirming our findings. Second, this is a single‐institution study and would require verification at another setting to add generalizability to our findings. The small sample size does not allow us to take into account other comorbidities or confounders that the patients had.

Overall, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first matched case–control study to compare the chemotherapy‐related complications in HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer with their HCV‐negative counterparts. This study provides evidence to the notion that chemotherapy adverse events are not well tolerated in patients with cancer with active HCV infection owing to associated comorbidities of the disease. Although our results are significant, the single‐institution, retrospective nature of this study prevents us from reaching a definitive conclusion on the tolerance of chemotherapy in HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer. Further studies that are prospective in nature and involve patients from multiple medical institutions are recommended in order to better understand the tolerance of chemotherapy in HCV‐positive patients with breast cancer. Additionally, studies to determine the feasibility of concurrent HCV treatment and chemotherapy are warranted.

Conclusion

Treatment delays in breast cancer have a negative effect on the overall survival of patients, and steps should be taken to avoid delays if possible. Our study suggests that chronic HCV infection in patients with breast cancer getting chemotherapy can be complicated because of treatment dose delays and dose modifications due to hematologically related adverse side effects. Future studies to examine the interaction between HCV and cytotoxic chemotherapy in breast cancer are warranted. Future studies should consider concurrent treatment for active HCV infection in patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Saptaparni Ghosh, Naomi Y. Ko

Provision of study material or patients: Naomi Y. Ko

Collection and/or assembly of data: Saptaparni Ghosh, Minghua L. Chen, Tsion Fikre, Naomi Y. Ko

Data analysis and interpretation: Saptaparni Ghosh, Minghua L. Chen, Janice Weinberg, Naomi Y. Ko

Manuscript writing: Saptaparni Ghosh, Tsion Fikre, Naomi Y. Ko

Final approval of manuscript: Saptaparni Ghosh, Minghua L. Chen, Janice Weinberg, Tsion Fikre, Naomi Y. Ko

Disclosures

Janice Weinberg: Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Data Monitoring Committees); Naomi Y. Ko: Pfizer (C/A). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda Rosen in the Boston Medical Center (BMC) cancer registry clinical data warehouse for help with identifying study subjects. This work was supported by the BMC Carter Disparities fund.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Hepatitis C. Available at http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Hepatitis C Questions and Answers for Health Professionals. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- 3. Hofmeister MG, Rosenthal EM, Barker LK et al. Estimating prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 2013‐2016. Hepatology 2019;69:1020–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nyberg AH, Chung JW, Shi JM et al. O058: Increased cancer rates in patients with chronic hepatitis C: An analysis of the cancer registry in a large U.S. health maintenance organization. J Hepatol 2015;62(suppl 2):S220. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Whiteman H. Hepatitis C linked to increased risk of liver cancer, other cancers. Medical News Today. Available at https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/293082.php. Accessed November 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Borchardt RA, Torres HA. Challenges in managing hepatitis C virus infection in cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:2771–2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . United States Cancer Statistics: Data Visualizations. Available at https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html. Accessed November 28, 2018.

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Basic Information About Breast Cancer. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/. Accessed February 18, 2019.

- 9. Breastcancer.org. U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics . Available at https://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/understand_bc/statistics. Accessed February 18, 2019.

- 10. Wiebe VJ, Benz CC, DeGregorio MW. Clinical pharmacokinetics of drugs used in the treatment of breast cancer. Clin Pharmacokinet 1988;15:180–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eklund JW, Trifilio S, Mulcahy MF. Chemotherapy dosing in the setting of liver dysfunction. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;19:1057–1063; discussion 1063–1054, 1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seeff LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002;36(5 suppl 1):S35–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ly A, Cheng HH, Alwan L. Hepatitis C infection and chemotherapy toxicity. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2019;25:474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matovina‐Brko G, Ruzic M, Fabri M et al. Treatment of acute hepatitis C in breast cancer patient: A case report. J Chemother 2014;26:180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morrow PK, Tarrand JJ, Taylor SH et al. Effects of chronic hepatitis C infection on the treatment of breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1233–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miura Y, Theriault RL, Naito Y et al. The safety of chemotherapy for breast cancer patients with hepatitis C virus infection. J Cancer 2013;4:519–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Talima S, Kassem H, Kassem N. Chemotherapy and targeted therapy for breast cancer patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Breast Cancer 2019;26:154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. D'Angelo S, Deutscher M, Dickler M et al. Hepatitis C virus infection does not preclude standard breast cancer‐directed therapy. Clin Breast Cancer 2009;9:51–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shoji H, Hashimoto K, Kodaira M et al. Hematologic safety of breast cancer chemotherapies in patients with hepatitis B or C virus infection. Oncology 2012;82:228–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Y, Li ZY, Wang JN et al. Effects of hepatitis C virus infection on the safety of chemotherapy for breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;164:379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Torres HA, McDonald GB. How I treat hepatitis C virus infection in patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood 2016;128:1449–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kish T, Aziz A, Sorio M. Hepatitis C in a new era: A review of current therapies. P T 2017;42:316–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roche B, Coilly A, Duclos‐Vallee JC et al. The impact of treatment of hepatitis C with DAAs on the occurrence of HCC. Liver Int 2018;38(suppl 1):139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/Infectious Diseases Society of America . Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. Available at https://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed July 1, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25. Torres HA, Mulanovich V. Management of HIV infection in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rudek MA, Flexner C, Ambinder RF. Use of antineoplastic agents in patients with cancer who have HIV/AIDS. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:905–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. American Cancer Society . How is cancer treated in people with HIV or AIDS? Available at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer‐causes/infectious‐agents/hiv‐infection‐aids/how‐is‐cancer‐treated.html. Accessed March 16, 2019.