Abstract

Objective:

Our aim was to investigate the association between LGA and stillbirth to determine if the LGA fetus may benefit from antenatal testing.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective cohort study of singleton ongoing pregnancies at 24 weeks gestation undergoing routine second trimester anatomy ultrasound from 1990-2009. Pregnancies complicated by fetal anomalies, aneuploidy, missing birthweight information and small for gestational age were excluded. Appropriate for gestational age (AGA) and LGA were defined as birthweight 10th-90th percentile and >90th percentile by the Alexander growth standard, respectively. The incidence of stillbirth was calculated as the number of stillbirths per 10,000 ongoing at risk pregnancies. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for LGA stillbirth compared to AGA stillbirth were estimated. The incidence and odds ratios for stillbirth were estimated at four week intervals from 24 weeks to ≥ 40 weeks gestation. Logistic regression was used to control for pre-existing and gestational diabetes.

Results:

Among 52,749 ongoing pregnancies at 24 weeks, there were 46,205 (87.2%) AGA and 6,544 (12.4%) LGA pregnancies. The risk of LGA stillbirth was greater than that of AGA stillbirth from 24 weeks, with a statistically significant difference starting at 36 weeks when the risk of LGA stillbirth was over three fold higher (26/10,000 LGA vs 7/10,000 AGA, aOR 3.10, 95% CI [1.68-5.70]). When women with diabetes were excluded in stratified analysis, pregnancies complicated by LGA continued to be at increased risk for stillbirth (18/10,000 vs. 7/10,000; aOR 2.63; 95% CI 1.27-5.43) ≥ 36 weeks.

Conclusion:

Pregnancies complicated by LGA are at a significantly increased risk for stillbirth at or beyond 36 weeks, independent of maternal diabetes status, and may benefit from antenatal testing.

Keywords: large for gestational age, stillbirth, antenatal testing, diabetes, gestational diabetes

Introduction:

In the United States, 1/200 pregnancies reaching 22 weeks gestation will result in stillbirth.1 There is a well-established association between the small for gestational age (SGA) fetus and stillbirth, but the risk of stillbirth in the large for gestational age (LGA) fetus (birthweight >90% for gestational age) remains unclear.2 Some population-based studies cite LGA as a possible hallmark of impending intrauterine death, and therefore a potential target for stillbirth prevention initiatives,3-5 while others show no increased risk of stillbirth in LGA compared to appropriate for gestational age (AGA) fetuses.6,7

In the setting of conflicting evidence, antenatal testing is not currently recommended for LGA.8 The aim of our study was to investigate the association between LGA and stillbirth. We hypothesize that LGA confers a significantly increased risk of stillbirth.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective cohort study of ongoing singleton pregnancies at 24 weeks gestation presenting to Washington University School of Medicine perinatal ultrasound units for routine second trimester anatomic survey from 1990-2009. The study was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board ID #201206058 and informed consent was obtained. Our medical center is an academic tertiary care center that serves as a major regional and national referral center. We used the previously validated Washington University perinatal database, a large system with dedicated research personnel for the collection and maintenance of data. Self-report questionnaires were used to collect maternal demographic information and medical and obstetric histories at the initial ultrasound visit. Follow-up information was obtained by trained research personnel from the medical record. If the patient delivered outside of the medical system, follow-up information was obtained via telephone contact with the patient or referring physician. Further details of data collection and management have been published previously.9

Ultrasound was performed by certified sonographers dedicated to obstetric and gynecologic examinations. Final diagnosis was made by the attending maternal fetal medicine physician. Gestational age was determined by the best obstetrical estimate based on established ACOG guidelines at the time the ultrasound was performed. Per entry criteria, all patients had an ultrasound between 16-24 weeks; therefore, all pregnancy dating was confirmed or dated by first or second trimester ultrasound.

AGA and LGA were defined as birthweight 10th-90th percentile and >90th percentile by the Alexander growth standard, respectively.10 There was no standard practice or protocol guiding clinical management of fetuses with an estimated fetal weight >90th percentile at our institution during the study period. In general, patients lacking diabetes screening at the time of diagnosis were offered screening, but there was no standard approach regarding antenatal testing or delivery timing. Women were identified as having GDM through the two-step screening test recommended by ACOG11using a 50 g oral glucose load with a 1 hour blood sugar cut-off of 140 mg/dL and a 3 hour glucose tolerance test using the National Diabetes Data Group diagnostic criteria.12 Type 1 or 2 diabetes diagnoses were determined as self-reported by the patient or documented by the medical team. Pregnancies complicated by fetal anomalies, aneuploidy, missing birthweight information, and small for gestational age were excluded.

The incidence of stillbirth was calculated as the number of stillbirths per 10,000 ongoing at-risk pregnancies. Within our database, stillbirth is defined as intrauterine fetal death at ≥20 weeks gestation, but deliveries at < 24 weeks of gestation were excluded from the analysis in accordance with the aim of our study. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for LGA stillbirth were compared to AGA stillbirth. The incidence and odds ratios for stillbirth were estimated at four week intervals from 24 weeks to ≥ 40 weeks gestation.

Baseline maternal characteristics were compared between women with LGA vs. AGA. Continuous variables were compared with descriptive and bivariate statistics using the unpaired Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normal distribution of continuous variables. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the crude and adjusted odds ratio for stillbirth among LGA pregnancies. Covariates for inclusion in the initial multivariable models were selected based on biologic plausibility and the results of the stratified analyses. Factors were removed in a backward stepwise fashion, based on significant changes in the adjusted odds ratio. The final model was adjusted for pre-existing and gestational diabetes. Final models were tested with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Stratified analysis was conducted by diabetes status. The statistical analysis was performed with STATA software (version 14, College Station, TX).

Results:

A total of 52,749 ongoing singleton pregnancies at 24 weeks met inclusion criteria. Of these, 46,205 (87.2%) were AGA and 6,544 (12.4%) were LGA. LGA occurred more often among women who were older, white, multiparous, and had higher BMI, compared to AGA fetuses (Table 1). Diabetes (either pre-existing or gestational) complicated 6.5% of AGA pregnancies and 12.2% of LGA pregnancies (p<0.01). Of 17 LGA stillbirths, 6 (35%) occurred in women with diabetes.

Table 1.

Maternal and pregnancy characteristics of Large for gestational age and Appropriate for gestational age pregnancies

| Characteristic | AGA (10-90th percentile) (n=46,205) |

LGA (>90th percentile) (n=6,544) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | 30.2 ± 6.3 | 31.6 ± 5.8 | < 0.01 |

| Race %(n) | |||

| Black | 22.5 (10,393) | 13.3 (870) | <0.01 |

| White | 61.7 (28,527) | 73.0 (4,776) | <0.01 |

| Other | 15.8 (7,285) | 13.7(898) | <0.01 |

| Nulliparous %(n) | 39.1 (18,046) | 27.9 (1,824) | <0.01 |

| BMI* | 25.0 ± 9.3 | 26.3 ± 10.2 | <0.01 |

| Any diabetes | 6.5 (2,988) | 12.2 (793) | <0.01 |

| Pre-existing diabetes | 1.7 (761) | 4.3 (284) | <0.01 |

| Gestational diabetes | 5.0 (2,308) | 8.2 (533) | <0.01 |

| Preeclampsia | 7.7 (3,501) | 6.3 (408) | <0.01 |

| 3rd trimester Ultrasound | 13.9 (6,415) | 14.5 (951) | 0.16 |

| Gestational age at delivery† | 39.1 (38.1, 40.0) | 39.4 (38.7, 40.3) | <0.01 |

mean ± standard deviation

median (interquartile range)

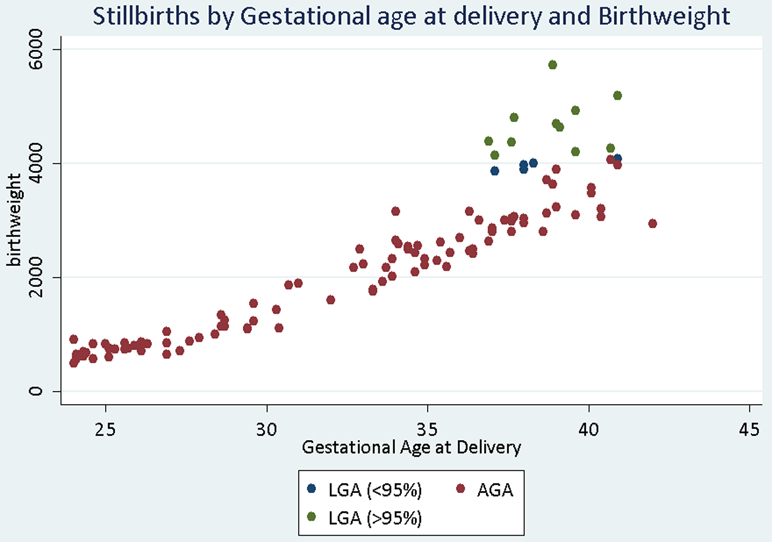

The risk of stillbirth at 24 weeks was 21/10,000 among AGA fetuses compared to 26/10,000 for LGA fetuses after adjusting for pre-existing and gestational diabetes (aOR 1.07; 95% CI [0.63-1.83]) (Table 2). The risk of LGA stillbirth was greater than that of AGA stillbirth at ≥24, ≥28 (26/10,000 vs. 15/10,000) and ≥32 (26/10,000 vs. 12/10,000). However, the differences were not statistically significant until ≥ 36 weeks. For pregnancies reaching 36 weeks gestation, the risk of LGA stillbirth was more than three-fold higher than AGA stillbirth (26/10,000 vs. 7/10,000; aOR 3.10, 95% CI [1.68-5.70]). All LGA stillbirths in the cohort occurred after 36+5 weeks gestation (Figure 1). Results were similar for LGA>95th% (data not shown) and the difference in stillbirth risk also achieved statistical significance at ≥ 36 weeks (24/10,000 vs 6/10,000; aOR 2.98, 95% CI [1.45-6.15]).

Table 2:

Incidence of Appropriate for gestational age and Large for gestational age stillbirth throughout gestation

| All Stillbirths/ 10,000 ongoing at risk pregnancies |

aOR (95% CI) for stillbirth*† |

Diabetes Stillbirths/ 10,000 ongoing at risk pregnancies with Diabetes |

OR (95% CI) for stillbirth* |

No Diabetes Stillbirths/ 10,000 ongoing at risk pregnancies without diabetes |

OR (95% CI) for stillbirth* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 24 weeks | ||||||

| AGA | 21 | Referent | 50 | Referent | 19 | Referent |

| LGA | 26 | 1.07 (0.63-1.83) | 76 | 1.51 (0.58-3.91) | 18 | 0.93 (0.48-1.80) |

| ≥ 28 weeks | ||||||

| AGA | 15 | Referent | 50 | Referent | 12 | Referent |

| LGA | 26 | 1.44 (0.83-2.50) | 76 | 1.50 (0.58-3.89) | 18 | 1.41 (0.72-2.78) |

| ≥ 32 weeks | ||||||

| AGA | 12 | Referent | 38 | Referent | 11 | Referent |

| LGA | 26 | 1.75 (1.00-3.07) | 76 | 2.01 (0.74-5.45) | 18 | 1.65 (0.83-3.27) |

| ≥ 36 weeks | ||||||

| AGA | 7 | Referent | 15 | Referent | 7 | Referent |

| LGA | 26 | 3.10 (1.68-5.70) | 78 | 5.11 (1.44-18.14) | 18 | 2.63 (1.27-5.43) |

| ≥ 40 weeks | ||||||

| AGA | 5 | Referent | 0 | Referent | 6 | Referent |

| LGA | 13 | 2.35 (0.61-9.11) | 0 | NA§ | 13 | 2.38 (0.61-9.21) |

OR for LGA stillbirth compared to AGA stillbirth in each category

Adjusted for diabetes (pre-gestational or gestational)

Adjusted analysis not performed due limited number of outcomes

Figure 1.

Stillbirths by gestational age at delivery and birthweight category

When results were stratified by the presence or absence of pre-existing or gestational diabetes (Table 2), there was not a statistically significant difference in stillbirth risk until ≥ 36 weeks in either group. Among women with diabetes, those with LGA were more likely to have a stillbirth ≥ 36 weeks (78/10,000 vs. 15/10,000; aOR 5.11; 95% CI 1.44-18.14). When women with diabetes were excluded, pregnancies complicated by LGA continued to be at increased risk for stillbirth (18/10,000 vs. 7/10,000; aOR 2.63; 95% CI 1.27-5.43) ≥ 36 weeks.

Discussion:

We found that LGA is an independent risk factor for stillbirth, but the presence of diabetes further increases this risk. The stillbirth risk for LGA pregnancies without diabetes is comparable to other common conditions for which antenatal testing is currently the standard of care, such as hypertensive diseases of pregnancy.13

The results of this study are consistent with the analysis by Bukowski et al., in a population-based, case-control study of all stillbirths and a representative sample of live births in 59 hospitals in the United States, which showed stillbirth was associated with both growth restriction and excessive fetal growth, with a stronger association with more severe LGA (>95th percentile).5 Conversely, a recent secondary analysis of a Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFMU) Network cohort of 50,374 women, assessing neonatal morbidity in LGA pregnancies reaching term,7 found no difference in rates of stillbirth between LGA and AGA pregnancies (1.5/1000 vs. 0.9/1000; aOR 1.64; 95% CI 0.79-3.42). The lower overall risk of stillbirth in this cohort, inclusion of only term pregnancies, and inclusion criteria defined by the primary MFMU network trials are important differences that may explain the discrepancy in findings.

A major strength of our study is the use of a large, validated, and well-maintained database to evaluate risks of rare outcomes such as stillbirth. The use of certified, dedicated and experienced sonographers as well as consistent guidelines for assignment of gestational age by ultrasound dating is another strength of the study. We utilized a measure, large for gestational age, that takes into account the gestational age of delivery rather than absolute macrosomia, which has been used in previous studies. Our study is also generalizable to current obstetric practices, as the current standard of care in the U.S. involves the initiation of antenatal testing when the risk of stillbirth is deemed sufficiently high, such as that of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. We assessed stillbirth risk across the full range of viable gestational ages and the cohort, which suggested the risks associated with LGA are not evenly distributed across gestational ages and seem to be negligible until 36 weeks.

Our results should be considered in the context of the following limitations. Although our database is large and well-maintained, the outcome of interest – stillbirth – is rare and therefore may have limited our ability to see differences in stratified analyses. As a retrospective, secondary analysis of prospectively collected data, we did not have information on prior pregnancies complicated by LGA, placental pathology, whether the stillbirth occurred antepartum or intrapartum, and our study is subject to selection bias. We were unable to identify the precise time of fetal death so gestational age was assigned based on delivery date rather than fetal demise date. It is possible that this introduced error into our weight for gestational age calculations among pregnancies with stillbirth. Similarly, our definitions of AGA and LGA were based on birthweight, rather than the fetal weight at the time of the stillbirth. However, this would be expected to similarly affect AGA and LGA stillbirth and bias our results towards the null hypothesis of no difference. In addition, we do not know how many obstetrics providers suspected LGA at the time of delivery and how this information may have influenced their management. However, one would presume that clinicians suspecting LGA or impending macrosomia would be more inclined to delivery those fetuses early, especially in the days prior to understanding the implications of early term births, which would have decreased the risk for stillbirth and biased our results to the null hypothesis. Finally, the cohort was drawn from a single, tertiary referral center. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to lower risk or community settings.

In conclusion, LGA confers a significantly increased risk of stillbirth for pregnancies reaching 36 weeks’ gestation, independent of maternal diabetes status. This suggests that there may be a late-pregnancy mechanism linking stillbirth and large for gestational age. It is biologically plausible that the metabolic demands of the LGA fetus may exceed the ability of the placenta to meet them, predisposing the fetus to stillbirth, but additional research is needed to determine the exact mechanism.

While the evidence for improved perinatal outcomes primarily comes from observational studies,14,15 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists suggest that antepartum fetal surveillance may be indicated when the risk of antepartum fetal demise is increased.8 The results of this study suggest that the LGA fetus may benefit from antenatal testing starting at 36 weeks. While there are no large, randomized trials to guide testing frequency, a reasonable strategy would be to initiate weekly or twice weekly testing with a non-stress test or biophysical profile at 36 weeks. In the setting of reassuring fetal testing, a reasonable delivery target would be 39 weeks in order to balance the risk of stillbirth with the risks associated with early term births.

Additional prospective research is needed to quantify the true stillbirth risk for the LGA fetus and whether antenatal testing has the potential to mitigate this risk. However, our findings suggest that the LGA fetus may benefit from antenatal testing starting at 36 weeks as a strategy to reduce the risk of stillbirth.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure: Drs. Carter and Trudell were supported by NIH T32 Grant #2T32HD055172-06 (PI G. Macones). At the time of investigation Dr. Trudell was supported by Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences Grant #UL1TR000448 (PI B. Evanoff). Dr. Carter is supported by a Robert Wood Johnson Grant #74250. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Presented as a poster at the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine 35th Annual Pregnancy Meeting, San Diego, CA February 2-7, 2015 Abstract # 281

References

- 1.Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, Frøen JF, Smith GC, Gibbons K, Coory M, Gordon A, Ellwood D, McIntyre HD, Fretts R, Ezzati M. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1331–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACOG practice bulletin No. 102: Management of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(3):748–761. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819e9ee2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray JG, Urquia ML. Risk of stillbirth at extremes of birth weight between 20 to 41 weeks gestation. J Perinatol. 2012;32(11):829–836. doi: 10.1038/jp.2012.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burmeister B, Zaleski C, Cold C, Mcpherson E. Wisconsin Stillbirth Service Program: Analysis of large for gestational age cases. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2012;158 A(10):2493–2498. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukowski R, Hansen NI, Willinger M, Reddy UM, Parker CB, Pinar H, Silver RM, Dudley DJ, Stoll BJ, Saade GR, Koch MA, Rowland Hogue CJ, Varner MW, Conway DL, Coustan D, Goldenberg RL. Fetal growth and risk of stillbirth: a population-based case-control study. PLoS Med. 2014;11(4):e1001633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vashevnik S, Walker S, Permezel M. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths in appropriate, small and large birthweight for gestational age fetuses. Aust New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(4):302–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendez-Figueroa H, Truong VTT, Pedroza C, Chauhan SP. Large for Gestational Age Infants and Adverse Outcomes among Uncomplicated Pregnancies at Term. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34(7):655–662. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1597325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Practice bulletin no. 145: Antepartum fetal surveillance. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):182–192. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000451759.90082.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odibo AO, Francis A, Cahill AG, MacOnes GA, Crane JP, Gardosi J. Association between pregnancy complications and small-for-gestational-age birth weight defined by customized fetal growth standard versus a population-based standard. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2011;24(3):411–417. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.506566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ALEXANDER GR, HIMES JH, KAUFMAN RB , MOR J MS, KOGAN M. United States National Reference for Fetal Growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(2):163–168. doi: 10.2144/000113869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulletins--Obstetrics C on P, Mellitus GD. Practice Bulletin No. 137: Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):406–416. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000433006.09219.f1; 10.1097/01.AOG.0000433006.09219.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavin III J, Alberti K, Davidson M, DeFronzo R, Drash A, Gabbe S, Genuth S, Harris M, Kahn R, Keen H, Knowler W, Lebovitz H, Maclaren N, Palmer J, Raskin P, Rizza R, Stern M. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(suppl 1):5–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2007.S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fretts RC. Etiology and prevention of stillbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(6):1923–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams KP, Farquharson DF, Bebbington M, Dansereau J, Galerneau F, Wilson RD, Shaw D, Kent N. Screening for fetal well-being in a high-risk pregnant population comparing the nonstress test with umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(5):1366–1371. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thacker SB, Berkelman RL. Assessing the diagnostic accuracy and efficacy of selected antepartum fetal surveillance techniques. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1986;41(3):121–141. doi: 10.1097/00006254-198603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]