Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic imposes a long period of stress on people worldwide and has been shown to significantly affect sleep duration across different populations. However, decreases in sleep quality rather than duration are associated with adverse mental health effects. Additionally, the one third of the general population suffering from poor sleep quality was underrepresented in previous studies. The current study aimed to elucidate effects of the COVID -19 pandemic on sleep quality across different levels of pre-pandemic sleep complaints and as a function of affect and worry.

Method

Participants (n = 667) of the Netherlands Sleep Registry (NSR) were invited for weekly online assessment of the subjective severity of major stressors, insomnia, sleep times, distress, depression, and anxiety using validated scales.

Analysis

To investigate the overall impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sleep quality of people with and without a history of insomnia, we performed a mixed model analysis using pre-pandemic insomnia severity, negative affect, and worry as predictors.

Results

The effect of COVID -19 on sleep quality differs critically across participants, and depends on the pre-pandemic sleep quality. Interestingly, a quarter of people with pre-pandemic (clinical) insomnia experienced a meaningful improvement in sleep quality, whereas 20% of pre-pandemic good sleepers experienced worse sleep during the lockdown measures. Additionally, changes in sleep quality throughout the pandemic were associated with negative affect and worry.

Conclusion

Our data suggests that there is no uniform effect of the lockdown on sleep quality. COVID-19 lockdown measures more often worsened sleep complaints in pre-pandemic good sleepers, whereas a subset of people with pre-pandemic severe insomnia symptoms underwent a clinically meaningful alleviation of symptoms in our sample.

Keywords: Insomnia, Sleep quality, COVID-19, Affect, Worry

Highlights

-

•

The effect of COVID -19 on sleep quality differs across participants, and depends on the pre-pandemic sleep quality.

-

•

A quarter of people with pre-pandemic (clinical) insomnia experienced a meaningful improvement in sleep quality.

-

•

Pre-pandemic good sleepers most often experienced worse sleep during the lockdown measures.

-

•

Changes in sleep quality throughout the pandemic were associated with negative affect and worry.

The lockdown measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have caused unprecedented changes in human behavior worldwide. Sleep is a physiological process which highly depends on environmental and social cues, and varies substantially with levels of stress [1]. Conceivably, environmental and social changes introduced by the pandemic were shown to affect sleep timing and duration in several recent studies across different populations [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. However, self-reported poor sleep quality rather than short sleep duration carries the strongest risk for adverse health consequences [6]. Moreover, most sleep studies on lockdown consequences included populations with few pre-pandemic sleep complaints, and underrepresent approximately one third of the general population with poor sleep quality, and 10% who fulfill the criteria of persistent insomnia disorder. In the current large-scale study, we therefore recruited a population with a balanced representation of good and poor sleepers, and focused on perceived sleep quality [as indicated by the insomnia severity index (ISI) [7], where higher scores indicate worse sleep quality]. We collected weekly logs of sleep and mood during an average of 3.3 ± 1.7 weeks of the lockdown. Participants further retrospectively indicated their sleep quality prior to the pandemic (retrospectively assessed for February 2020). A subset of participants (n = 413, 61.9%) completed reports on their self-perceived sleep quality prior to the pandemic (data collected between May 2012 and December 2019). We found that there is no uniform effect of the lockdown on perceived sleep quality. Marked individual differences in individual response to the lockdown would have been overlooked by simply calculating a whole-sample mean change. The lockdown on average worsened sleep in people that were previously good sleepers. In contrast, one out of four people with pre-pandemic clinical insomnia experienced a meaningful sleep improvement. Additionally, we observed that variability in self-reported sleep quality during lockdown was associated with changes in negative affect and worry.

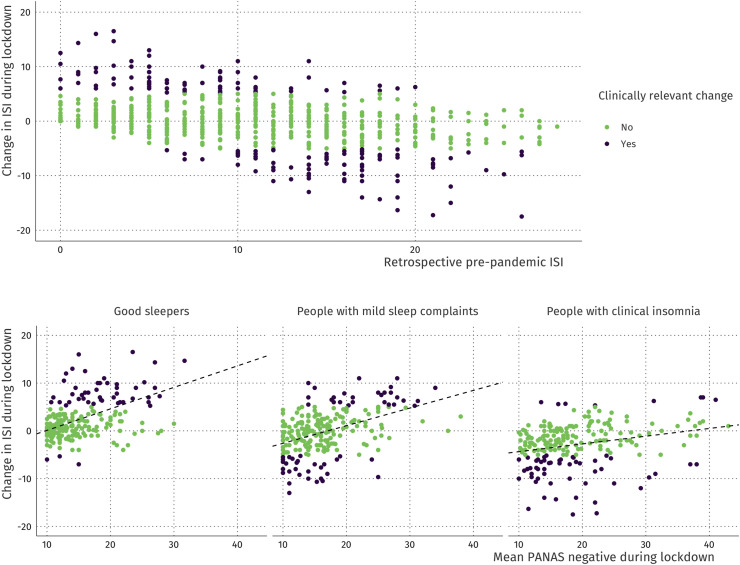

Participants completed the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; range 0–28) on their perceived sleep quality. Of the 667 participants in the current study, 221 (33.1%) were good sleepers (ISI scores 0–7), 233 (34.9%) had mild sleep complaints (ISI scores 8–14), and 213 (31.9%) had clinical insomnia (ISI scores 15–28) before the pandemic [7]. We inspected whether self-reported sleep quality changed meaningfully during the lockdown, where we defined meaningful change as a minimum of six-point absolute change as suggested by Yang et al. [8]. Weekly assessments during the lockdown (March 15th 2020 onwards) revealed a meaningful change in 169 (25.3%) of the participants, which occurred equally often in all three groups [ie, 51, 57, and 61, respectively; χ2(2) = 1.92, p = 0.38; Fig. 1 A]. However, the direction of change differed [χ2(2) = 73.03, p < 0.001], such that the majority of changing pre-pandemic good sleepers experienced worsening of sleep quality, whereas the majority of people with prepandemic clinical insomnia who experienced sleep changes most often experienced sleep improvement. In interpreting the direction of change it is important to highlight that following our definition of meaningful change, people that already slept good before the pandemic (ie, an ISI score below six) or people that slept very poorly before the pandemic (ie, an ISI score above 22) could only experience meaningful change in one direction. Nevertheless, 84% of the people with pre-pandemic clinical insomnia had a pre-pandemic ISI score of 22 or less, allowing them to have meaningful change in sleep quality in both directions (See Fig. 1). Despite the possibility to either worsen or improve in sleep quality, of the people with pre-pandemic clinical insomnia who changed meaningfully, 86.9% showed an improvement in sleep quality.

Fig. 1.

Association between retrospective pre-pandemic insomnia severity and changes in sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinically meaningful changes absolute difference ≥ 6 points [7]; are shown in dark purple, whereas non-meaningful changes are coloured green. The lower panel shows the relationship between the mean negative affect during the pandemic and changes in sleep separately for pre-pandemic good sleepers, people with mild sleep complaints, and people with (clinical) insomnia. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has been reported to negatively affect mental health [[9], [10], [11]]. It was therefore surprising to find that the lockdown elicited a clinically meaningful sleep improvement in a quarter of the people that suffered from insomnia prior to the lockdown whereas previous studies reported no changes [4,12] or a slight decrease [2,3] in sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the implications of the lockdown are not the same for everyone and differential emotional responses, including attenuation of negative affect [13], towards the pandemic have been reported [2,14]. Since individual differences in experiences and attitudes throughout the pandemic might be best captured in negative affect (eg “irritable”, “nervous”, “distressed”) and worry, we investigated whether these are related to the observed changes in sleep. In our sample, negative affect and worry significantly predicted sleep quality throughout the pandemic. Specifically, pre-pandemic good sleepers who had experienced a stronger worsening of sleep also experienced more negative affect during the lockdown (Fig. 1, lower panel left). Likewise, people with pre-pandemic clinical insomnia who experienced a stronger amelioration of insomnia experienced less negative affect during the lockdown (Fig. 1, lower panel right).

In conclusion, we found profound individual differences in the effect of the lockdown measures on perceived sleep quality. Importantly, this effect could go both ways: some people experienced improved sleep quality whereas others experienced worsened sleep quality during the pandemic. We further observed that the severity of negative affect and worry experienced during the “intelligent lockdown” was related to the change in perceived sleep quality. An improved understanding of this interplay may ultimately inform strategies to alleviate sleep problems and deteriorating mental health.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Desana Kocevska: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Tessa F. Blanken: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Eus J.W. Van Someren: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing, Supervision. Lara Rösler: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tom Bresser, Oti Lakbila-Kamal, Stefanie Hölsken, Glenn van der Lande, Jeanne Leerssen, Joyce Reessen and Laura Vergeer for their help with the study preparation.

Footnotes

The work was funded by NWA Startimpuls Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences 2017 Grant (AZ/3137) and by the European Research Council grant ERC- 2014-AdG-671084 INSOMNIA.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest associated with this article can be viewed by clicking on the following link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.09.029.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.09.029.

Conflict of interest

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Fortunato V.J., Harsh J. Stress and sleep quality: the moderating role of negative affectivity. Pers Indiv Differ. 2006;41:825–836. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blume C., Schmidt M.H., Cajochen C. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on human sleep and rest-activity rhythms. Curr Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cellini N., Canale N., Mioni G. Changes in sleep patterns, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J Sleep Res. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jsr.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leone M.J., Sigman M., Golombek D.A. Effects of lockdown on human sleep and chronotype during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Biol. 2020;30(16):R930–R931. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright K.P., Linton S.K., Withrow D. Sleep in university students prior to and during COVID-19 stay-at-home orders. Curr Biol. 2020;30(14):R797–R798. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang N.K., Fiecas M., Afolalu E.F. Changes in sleep duration, quality, and medication use are prospectively associated with health and well-being: analysis of the UK household longitudinal study. Sleep. 2017;40(3):zsw079. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastien C.H., Vallières A., Morin C.M. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia Research. Sleep Med. 2011;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang M., Morin C.M., Schaefer K. Interpreting score differences in the Insomnia Severity Index: using health-related outcomes to define the minimally important difference. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(10):2487–2494. doi: 10.1185/03007990903167415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. pmid: 32302935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torales J., O'Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J.M. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. 0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celenay S.T., Karaaslan Y., Mete O. Coronaphobia, musculoskeletal pain, and sleep quality in stay-at home and continued-working persons during the 3-month Covid-19 pandemic lockdown in Turkey. Chronobiol Int. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1815759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lades L., Laffan K., Daly M. Daily emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Health Psychol. 2020 Jun 23 doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kantermann T. How a global social lockdown helps to unlock time for sleep. Curr Biol. 2020;30 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.