Summary:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates critical, context-dependent transcription in numerous physiological events. Amongst the well-documented mechanisms affecting Wnt/β-catenin activity, modification of N-glycans by L-fucose is the newest and the least understood. Using a combination of Chinese hamster ovary cell mutants with different fucosylation levels and cell-surface fucose editing (in situ fucosylation; ISF), we report that α(1–3)-fucosylation of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) in the Galβ(1–4)-GlcNAc sequences of complex N-glycans modulates Wnt/β-catenin activity by regulating the endocytosis of low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6). Pulse-chase experiments reveal that ISF elevates endocytosis of lipid-raft-localized LRP6, leading to the suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Remarkably, Wnt activity decreased by ISF is fully reversed by the exogenously added fucose. The combined data show that in situ cell-surface fucosylation can be exploited to regulate a specific signaling pathway via endocytosis promoted by a fucose binding protein, thereby linking glycosylation of a receptor with its intracellular signaling.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In the modern era of molecular medicine prodigious effort has been devoted to dissecting the functions of signaling pathways and the underlying molecular mechanisms. Despite the known involvement of glycans on cell-surface glycoproteins in numerous signaling pathways, their specific contributions to pathway activities are understood in only a few cases, including O-glycans regulation of Notch signaling(Varshney and Stanley, 2018), and sialic acid and Fuc regulation of EGF receptor signaling(Y. C. Liu et al., 2011).

It is challenging to study the impact of glycosylation on a specific signaling pathway. This is partly because glycosylation is a posttranslational modification and not under direct genetic control. Most methods to manipulate glycosylation patterns alter glycosylation status globally rather than on a particular or a restricted number of glycoproteins. However, by overexpressing a protein of interest, or mutating glycosylation sites in a particular glycoprotein, the impact of glycans on protein functions in a specific pathway can be singled out. Likewise, using a combination of glycan engineering tools and inhibitors of a signaling pathway, specific roles of glycans in modulating this pathway can be elucidated by monitoring signaling output.

Wnt signaling is an evolutionarily conserved pathway that regulates cell fate determination, cell migration, cell polarity, neural patterning and organogenesis during embryonic development.(Clevers and Nusse, 2012; Nusse and Clevers, 2017) Aberrant regulation of this pathway is associated with a variety of diseases, including cancer, fibrosis and neurodegeneration.(Clevers and Nusse, 2012; Nusse and Clevers, 2017) The Wnt pathway is commonly divided into β-catenin-dependent (canonical) and -independent (non-canonical) signaling.(Clevers and Nusse, 2012; Nusse and Clevers, 2017) The canonical pathway is activated upon binding of secreted Wnt ligands (such as WNT3a and WNT1) to Frizzled receptors (FZD) and co-receptors LRP5 (low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5) or LRP6.(Bilic et al., 2007; Tamai et al., 2000; Yamamoto et al., 2008) Binding of ligand relays a signal through Dishevelled, resulting in stabilization and nuclear entry of β-catenin. In the nucleus, β-catenin forms an active complex with LEF (lymphoid enhancer factor) and TCF (T-cell factor) families of transcription factors to promote expression of specific genes.

Previously, we discovered that increasing cell surface N-glycan fucosides through the over-expression of the GDP-Fuc transporter SLC35C1 (solute carrier 35C1, a GDP-Fuc transporter) inhibits canonical Wnt signaling during zebrafish embryogenesis.(Feng et al., 2014) However, the mechanism by which inhibition occurs remained unknown. Both WNT and WNT-receptors are fucosylated,(Janda et al., 2012; Jung et al., 2011), and in certain cancer cell lines such as the lung cancer cell line A549, LRP6 is also fucosylated (Fig. S1A). Structural analysis revealed that N-glycans in both WNT8 and FZD 8 cysteine-rich domains are solvent-exposed and do not appear to contribute directly to WNT-FZD interactions.(Janda et al., 2012) Therefore, we sought to determine if changes in cell-surface fucosylation that reduce Wnt signaling(Feng et al., 2014) might influence the function of LRP co-receptors.

In this study, we use a combination of CHO glycosylation mutants and fucosyltransferase-mediated cell-surface chemoenzymatic in situ fucosylation (ISF), to show that increasing cell-surface N-glycan fucosylation enhances the endocytosis of lipid-raft-localized LRP6, which in turn, suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling. This inhibition can be fully reversed by externally added free fucose in medium, suggesting the existence of a fucose-binding protein that regulates the endocytosis of fucosylated LRP6. Aberrant glycosylation is a hallmark of cancer, and cancer-related changes in fucosylated N-glycans are often observed. Cancer cells may exploit fucosylation to alter Wnt signaling and thus promote the survival or proliferation of tumors.

Results

ISF inhibits canonical Wnt signaling in zebrafish embryos

Previously, we reported that over-expression of the GDP-Fuc transporter SLC35C1 specifically inhibits canonical Wnt signaling by increasing the levels of cell-surface N-linked fucosides.(Feng et al., 2014) However, manipulating the SLC35C1 level is an indirect means of regulating fucosylation of cell-surface N-glycans. To tune cell-surface glycan fucosylation level directly, we used a technique we term ISF. This strategy exploits a recombinant H. pylori α1–3-fucosyltransferase (FucT) to transfer a Fuc residue from the GDP-Fuc donor to the C3-OH of GlcNAc in a LacNAc unit.(Wang et al., 2009) LacNAc is abundantly expressed in complex and hybrid N-glycans. Using this technique, Fuc can be added directly to cell surface glycans of cultured cells and living organisms.(Varki et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2011)

However, the formation of the zebrafish enveloping layer (EVL)—the monolayer of cells surrounding zebrafish embryos—prevents the use of ISF to modify inner cells of the embryo covered by the EVL.(Kimmel et al., 1995) The EVL first appears at the blastula stage [4.66 hours post fertilization (hpf)] and eventually forms a sealed layer at approximately 90% epiboly (stage 9 hpf).(Kimmel et al., 1995) To modify the inner part of zebrafish embryos, we devised a new strategy to apply ISF at the 8-cell stage (1.25 hpf) of zebrafish embryogenesis by injecting FucT and GDP-Fuc (or its alkyne-tagged analogue GDP-FucAl) directly beneath the chorion (Fig. S1B).(Zheng et al., 2011) Via this strategy, the ISF system could gain access to all the cells of the embryo, and the sealed chorion served as a natural reaction vessel. After 28 ºC-incubation for several hours, we fixed the embryos at 7 hpf (70% epiboly stage), and performed the ligand (BTTPS)-assisted copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne [3+2] cycloaddition reaction (CuAAC)(Wang et al., 2011) using Alexa Fluor-488 azide to detect the incorporated alkynyl fucose. All cells throughout the GDP-FucAl-treated embryos exhibited strong Alexa Fluor-488 fluorescence, while only background fluorescence was observed in control embryos that were treated with FucT and unmodified GDP-Fuc (Fig. 1A, and Fig. S1B).

Figure 1.

Enhanced α(1–3)-fucosylation via ISF inhibits Wnt signaling in zebrafish embryos, CHO parent and Lec2 cells.

(A) Relativye mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of traditional bioorthogonal chemical reporter labeling in the FucT/GDP-Fuc or FucT/GDP-FucAl treated embryos by ImageJ. (B) Flow chart of the impacts of ISF on Wnt signaling activity in a zebrafish Wnt reporter line. At the 8-cell stage, a FucT/GDP-Fuc pre-mixture, or FucT only, were injected into the chorion to perform ISF or act as control, respectively. To further boost the Wnt signaling readout, recombinant WNT8a was injected into the chorion at the 1000-cell stage before the embryos were transferred individually into single wells. Expression of the GFP reporter was quantified at 7 hpf. (C) Comparing the GFP expression level of Wnt reporter embryos treated by ISF or FucT only in the presence or absence of WNT8a. The MFI of GFP was quantified for healthy live embryos at 7 hpf by subtracting background in samples with no GFP expression, and the GFP-MFI of embryos treated with FucT only was set as 100%. The numbers on the bar graph represent the numbers of healthy embryos used in this assay. (D) Typical complex N-glycans present on cell surface glycoproteins of CHO Pro-5 cells, and glycosylation mutants Lec2, LEC30 and Lec8 cells.(North et al., 2010) Pro-5 and Lec2 cells carry LacNAc with no Fuc attached and are excellent substrates for ISF. Lec8 has no LacNAc and LEC30 has many fucosylated LacNAcs. Sugar symbols are from the Symbol Nomenclature for Glycans (SNFG).(Neelamegham et al., 2019) (E) Comparison of Wnt activity in Pro-5 cells compared to LEC30 cells in the presence or absence of WNT8a. (F) Western blot assay for detection of biotinylated glycoproteins in Pro-5 cells generated via GDP-Fuc-biotin-ISF before or after PNGase F-treatment. Equal loading determined by Coomassie blue staining (lower panel). (G) Comparison of Wnt activity in CHO parent and three mutant lines treated with ISF or FucT only. (H) Quantitative flow cytometry analysis of time-dependent incorporation of α(1–3) Fuc onto Pro-5 cell-surface glycans via ISF-treatment. (I) Time-dependent decrease of Wnt activity in Pro-5 cells treated by ISF. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three biological replicates. In A and B, results are from the same set of samples and the signal intensity of sample at 0 min treatment is set as 100%. (J) Time-dependent decrease of the β-catenin level in ISF-treated Pro-5 cells. Western blot of anti-β-catenin (upper panel) and actin (lower panel). In Figure 1J, the numbers indicate the relative quantification of anti-β-catenin level to actin by ImageJ. The 30 min, non-treated sample was set as 100%. Number (in white) indicates the relative β-catenin level normalized to corresponding level of actin. * unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; NS, not significant.

Signaling reporter lines have been used extensively in zebrafish research.(Moro et al., 2013; Weber and Köster, 2013) Currently, the most sensitive, stable transgenic zebrafish line carrying a Tcf/Lef-miniP:dGFP Wnt signaling reporter was generated by the Ishitani group.(Shimizu et al., 2012) In this reporter line, GFP is detectable in all known Wnt/β-catenin signaling-active cells during embryogenesis, starting as early as 3.7 hpf.(Shimizu et al., 2012) We utilized this reporter line to examine the impact of ISF on Wnt activity. We first treated embryos with FucT and GDP-Fuc or with FucT only at the 8-cell stage (Fig. 1B). At the 1000-cell stage, or approximately 3 hpf, ISF-modified or unmodified embryos were injected into the chorion with recombinant WNT8a (500 pg)—the main canonical Wnt ligand naturally expressed during gastrulation(Fekany et al., 1999; Kelly et al., 2000; Langdon and Mullins, 2011; Schier and Talbot, 2005)—or left untreated. After the treatment, each embryo was transferred into a well of a 96-well plate and kept at 28 ºC to continue development. GFP-associated fluorescence was quantified at 7 hpf. As shown in Fig. 1C, in the presence of exogenously added WNT8a, we observed stronger Wnt-signaling associated GFP fluorescence. As expected, embryos modified by ISF exhibited decreased GFP fluorescence compared with control embryos treated with FucT only.

N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation level is negatively correlated with canonical Wnt activity

To elucidate potential mechanisms by which fucosylation regulates canonical Wnt signaling, we used a combination of ISF and CHO glycosylation mutants with distinct fucosylation of cell-surface glycoproteins. Four CHO lines, Pro-5 parent(Stanley et al., 1975), and three glycosylation mutants, Lec2(Deutscher et al., 1984; Eckhardt et al., 1998; Stanley and Siminovitch, 1977), Lec8(Deutscher and Hirschberg, 1986; Eckhardt et al., 1998; Oelmann et al., 2001; Stanley, 1981) and LEC30(Patnaik et al., 2000; Potvin and Stanley, 1991), were chosen for this study. Typical N-glycans synthesized by each cell line are depicted in Fig. 1D.(North et al., 2010) Pro-5 are the parental CHO cells from which Lec2, Lec8 and LEC30 were derived.(Janda et al., 2012; Jung et al., 2011; Patnaik and Stanley, 2006) Pro-5 cells add Fuc to the N-glycan core GlcNAc and sialic acid to N-glycan antennae, but no fucosylation is found in terminal or internal LacNAc units of complex N-glycans. Lec2 cells express similar N-glycans to Pro-5 cells, but they terminate mainly in Gal having very few sialic acid residues due to an inactive Golgi CMP-sialic acid transporter. Lec8 cells have an inactive Golgi UDP-Gal transporter, and therefore their complex N-glycans terminate in GlcNAc with few, if any, having terminal LacNAc.(Kawar et al., 2005; North et al., 2010) The activation of Fut4 and Fut9 genes produces the gain-of-function mutant LEC30, which exhibits a significantly increased level of α1–3-fucosylation of LacNAc in N-glycan antennae.(North et al., 2010)

To assess if changes in cell-surface N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation have any impact on canonical Wnt signaling in these CHO glycosylation mutants, we examined the effect of ISF on Wnt activity in Pro-5, Lec2 and LEC30 cells. Lec8 cells, with no LacNAc in N-glycans, were used as a negative control. The Wnt signaling activity in these cell lines was measured using a luciferase reporter assay,(Veeman et al., 2003), and the cell-surface α1–3-fucosylation level was characterized using a Fuc-specific lectin, Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL). As shown in Fig. 1D-J, Wnt activity negatively correlated with increased cell-surface LacNAc fucosylation level. In the presence or absence of exogenously added WNT8a, endogenously fucosylated LEC30 cells exhibited significantly lower Wnt activity compared to Pro-5 cells with no endogenous LacNAc fucosylation (Fig. 1E). After ISF, the N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation level of Pro-5 cells was significantly elevated, but the same treatment caused almost no increase in the LacNAc fucosylation status of LEC30 cells (Fig. 1F, and Fig. S1C). Consistent with this observation, Wnt signaling in Pro-5 cells was significantly suppressed by ISF, but the same treatment had little influence on Wnt activity in LEC30 cells (Fig. 1G, and Fig. S1D). As expected, ISF had a similar impact on Wnt signaling in both Pro-5 and Lec2 cells and no influence on Wnt activity was observed in Lec8 cells following ISF. Finally, using GDP-fucose-biotin as the donor substrate for ISF and PNGase-F to remove N-glycans, we confirmed that the newly added Fuc residues were mainly located on N-glycans of Lec2 and Pro-5 cells (Fig. 1F, and Fig. S1E). This was expected because these CHO cell lines do not synthesize O-GalNAc glycans with LacNAc.(North et al., 2010)

The above results suggested that Wnt activity is negatively correlated with the level of cell-surface N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation (Fig. 1G). To further investigate, we performed a time-lapse experiment to evaluate the impact of ISF on Wnt activity. In this experiment, Pro-5 CHO cells were incubated with FucT and GDP-Fuc to perform cell surface ISF. At 30 min intervals, cell-surface fucosylation levels and intracellular β-catenin levels were quantified. Also, at each time point, the treated cells were analyzed by the luciferase reporter assay to evaluate Wnt activity. As revealed by quantitative flow cytometry analysis, the N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation level increased in the first hour of treatment before reaching a plateau (Fig. 1H). As expected, the longer ISF treatment was, the less Wnt activity was observed (Fig. 1I), which was accompanied by a continuing decrease in β-catenin levels (Fig. 1J).

Next, we blocked the degradation of β-catenin by adding a non-degradable β-catenin or a small-molecule inhibitor, CHIR99021, that inhibits β-catenin degradation.(Lee and De Camilli, 2002) Both approaches were effective at rescuing ISF-induced Wnt inhibition in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S2), indicating that Wnt inhibition caused by ISF is upstream of β-catenin degradation.

N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation increases LRP6 expression at the cell surface with concomitant Wnt inhibition

Wnt signaling is regulated at multiple levels, but the major mechanism known to degrade Wnt ligand is mediated by WNT-FZD-LRP6 endocytosis. Tuning the stability and localization of LRP6 can therefore control Wnt activity.(Yamamoto et al., 2008) In general, Wnt activity is positively correlated with cellular LRP6 levels.(Khan et al., 2007; Mao et al., 2001; Tamai et al., 2000) However, in our previous work we found that when Wnt activity was inhibited by elevated N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation induced by SLC35C1 over-expression, LRP6 protein level was increased.(Feng et al., 2014) We now report that the same phenomenon was observed in CHO cells. When Pro-5 cells were subjected to ISF, total LRP6 protein level was elevated along with increased cell surface N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation (Fig. 2A and 2B). This observation suggested that LRP6 expression or stability at the cell surface may be linked to N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation.

Figure 2.

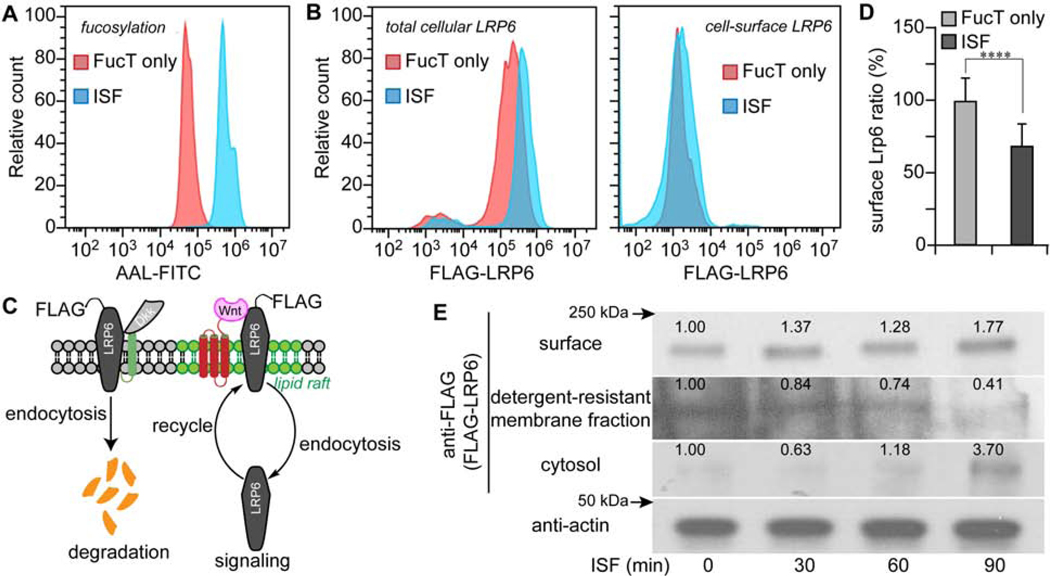

ISF treatment relocates LRP6 from detergent-resistant membranes to cytoplasm.

(A, B) Flow cytometry histograms of FucT-treated (Red) and ISF-treated (Blue) Pro-5 CHO cells after 90 min incubation. LRP6 in (B) was transiently-expressed FLAG-LRP6. (A) Detection of cell surface N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation by the lectin AAL-FITC. (B) Immunofluorescent staining of total cellular LRP6 and cell-surface LRP6. (C) Scheme of LRP6 location and maintenance regulated by endocytosis. (D) Ratio of LRP6 (surface to total) in Pro-5 cells treated by ISF, or FucT only. Mock control was set as 100%. Error bars show standard error. N=53,664 cells, **** unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test (p<0.001). (E) Western blot assay of membrane LRP6, lipid raft LRP6, cytoplasmic LRP6 and actin after different times of ISF treatment. Number indicates the relative LRP6 level normalized to the corresponding level of actin.

N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation relocates the LRP6 protein from detergent-resistant membrane to the cytoplasm

As presently understood, LRP6 stability is controlled by Dickkopf (Dkk) through a specific endocytosis pathway. Dkk antagonizes Wnt signaling by binding to Kremen and LRP6, forming a complex, which is then endocytosed through clathrin-mediated endocytosis, leading to LRP6 degradation.(Mao et al., 2001) On the other hand, the WNT-FZD-LRP6 complex formed by WNT with LRP6 and Frizzled is endocytosed through the caveolin-mediated endocytosis pathway.(Bilic et al., 2007; Yamamoto et al., 2006) After the complex sends a signal to inhibit β-catenin degradation, LRP6 is recycled (Fig. 2C).(Yamamoto et al., 2008) We hypothesized that N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation may elevate LRP6 protein level by affecting endocytosis or degradation.

To test these hypotheses, we first assessed the cellular distribution of LRP6 in Pro-5 CHO cells before and after ISF using both flow cytometry and Western blot analyses. For flow cytometry analysis, we expressed a N-terminal FLAG-tagged LRP6, a previously used strategy for LRP6 tracing and functional study.(G. Liu et al., 2003; Mao et al., 2001) The antibody staining of FLAG on live cells detected surface-localized LRP6, while the total LRP6 was determined following fixation and permeabilization of the cells. Raft proteins in the detergent-resistant fraction(Brown, 2006; Waugh, 2016) were re-suspended in 10% SDS buffer and isolated using streptavidin-beads immunoprecipitation. With cell surface N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation increased by ISF (Fig. 2A), the total amount of cellular LRP6 was found to double (Fig. 2B). At the same time, cell-surface LRP6 increased only slightly. This unexpected result indicated that increased LRP6 was primarily located inside the cell. Determining the ratio of surface to total LRP6 after ISF revealed that the relative proportion of cell surface LRP6 had decreased by approximately 30% (Fig. 2D).

It was reported that only the LRP6 residing in lipid rafts can form a complex with WNT and FZD.(Özhan et al., 2013; Yamamoto et al., 2008) We examined the distribution of LRP6 on the cell surface, in lipid rafts and inside the cell using differential biotinylation and Western blot analysis. At various time points following ISF, cell-surface protein was biotinylated. After cell lysis, RIPA buffer was used to extract the soluble fraction, separating the insoluble, lipid raft fraction. We then used streptavidin-beads to enrich biotinylated proteins from the soluble fraction. Finally, lipid raft proteins in the insoluble fraction were resuspended in 10% SDS buffer and isolated using anti-biotin immunoprecipitation.(Brown, 2006; Waugh, 2016)

Western blot analysis revealed that cell surface LRP6 increased slightly after ISF (Fig. 2E top panel). By contrast, the level of LRP6 in the cytoplasm increased notably (Fig. 2E third panel), with a concomitant decrease in the detergent-resistant LRP6 fraction (i.e., lipid-rafts). By 1.5 hrs following ISF, LRP6 in the detergent-resistant fraction almost disappeared. Together, these results and former reports(Yamamoto et al., 2008) provided strong evidence that ISF led to the internalization of LRP6 from lipid rafts, presumably via an increase of endocytosis.

To further investigate the cellular redistribution of LRP6 induced by ISF, we performed an imaging experiment to analyze the colocalization of LRP6 and Cholera toxin subunit B (CTB),(Janes et al., 1999) a marker for lipid rafts (Fig. 3A). The colocalization of LRP6 and CTB was found both on the cell surface and in the cytoplasm. After treating cells with ISF for 30 min, the percentage of cell surface, colocalized LRP6 and CTB dropped from approximately 50% per cell in non-treated cells to ~14% per cell in ISF-treated cells (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the overall colocalization also decreased from ~8% per cell to ~2% per cell after ISF (Fig. 3C). Consistent with this observation, the colocalization of LRP6 and CTB was significantly lower in the highly fucosylated LEC30 cells compared to Pro-5 cells that have no endogenous N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

ISF relocalizes LRP6 away from lipid rafts.

(A) A schematic representation (top panel) of the membrane topological location of the lipid-raft marker CTB and LRP6. The colocalization of LRP6 and CTB (white dots) in lipid rafts was calculated from confocal images using ImageJ, based on immunofluorescence of antibody to LRP6 (green) and labeled CTB (red). (B) Comparing the colocalization of LRP6 and CTB showed that LRP6 moved from membrane to cytoplasm in ISF-treated Pro-5 cells. The numbers show the cells counted in this assay. (C, D) Plots of the colocalization of LRP6 and CTB (per cell) in ISF-treated and FucT-treated Lec2 cells (C) or in untreated LEC30 cells (D). Colocalization was measured by ImageJ and is indicated by white dots. Note: ****, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test p<0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm.

ISF enhanced the endocytosis of LRP6

To determine if the re-localization of LRP6 was mediated through endocytosis, we examined the co-localization of LRP6 and specific endosomal markers, RAB5, an early endosomal marker; RAB7, a marker of late endosomes (LE)(Vonderheit and Helenius, 2005) which is involved in the transfer of cargo to lysosomes for degradation, and RAB11,(Ullrich et al., 1996) a marker of recycling endosomes (RE). In this experiment, we expressed FLAG-LRP6 in CHO cells and then pulse-labeled the surface LRP6 using anti-FLAG antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 for 30 min. Then we chased the location of fluorescent-labeled LRP6 after ISF treatment.

We found that ISF increased the colocalization of LRP6 and RAB5-mCherry shortly after the initiation of pulse labeling. However, without ISF-treatment, there was essentially no colocalization of LRP6 and RAB5. By contrast, after ISF we could clearly detect formation of large clusters of colocalized LRP6 and RAB5 (Fig. 4A, 2nd and 3rd panel). Subsequently, we analyzed the colocalization of LRP6 with RAB11 (Fig. 4B and 4E), RAB5 (Fig. 4C) and RAB7 (Fig. 4D and Fig. S3), respectively, using ImageJ to calculate Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC). The value of PCC defines the colocalization between two factors. A PCC value of 1 means total colocalization; 0 means random localization between two locations; and −1 means the two factors are not colocalized. As shown in Fig. 4D, ISF did not induce any notable changes in colocalization between LRP6 and RAB7. However, the colocalization of LRP6 with Rab11 increased significantly by 30 minutes following ISF (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Tracking LRP6 endocytosis induced by ISF.

(A, B) Confocal visualization of LRP6 (FLAG-LRP6, green) in FucT only-treated and ISF-treated Pro-5 cells. Early endosome marker RAB5-mCherry (A, red) and recycling endosome marker RAB11-mCheery (B, red) were transiently expressed in Pro-5 cells. The colocalization of LRP6 with RAB5 or RAB11 is shown in yellow. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C-E) Colocalization of RAB5 (C), RAB7 (D) or RAB11 (E) with LRP6 in FucT-only-treated and ISF-treated Pro-5 cells, is shown as Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC). Note: **, two-sided Student’s t test p<0.01; NS, not significant.

Enhancing endocytosis also increases N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation-mediated Wnt inhibition, whereas decreasing endocytosis rescues the inhibition

To further investigate whether N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation-induced Wnt inhibition occurs through an endocytic process, we sought to perturb the status of dynamin, a GTPase responsible for endocytosis and other vesicular trafficking processes (Lee and De Camilli, 2002). The dynamin family has three members that share high structural homology. We over-expressed dynamin-1 to artificially enhance endocytosis (Lee and De Camilli, 2002), and used dominant-negative (DN) dynamin-1 over-expression or Dynasore, a classical dynamin inhibitor.(Macia et al., 2006) to inhibit endocytosis. Under these conditions, we quantified the ratio of Wnt activity in ISF-treated Pro-5 cells to that of Pro-5 cells treated with FucT only. Alternatively, we quantified the ratio of Wnt activity in LEC30 to that of Pro-5 cells. This ratio directly reflects the effect of Wnt inhibition. The lower the ratio became, the more severe the inhibition of Wnt signaling that occurred.

We observed that transient expression of dynamin-1 decreased the ratio of Wnt activity in ISF- versus FucT-only treated Pro-5 cells, and the decrease was positively correlated with the amount of dynamin-1 expressed (Fig. S4A). This result strongly suggests that decreased dynamin-1 activity and endocytosis mimics the increased Wnt activity of cells that do not have fucosylated LacNAc on cell surface glycoproteins. Accordingly, treatment by Dynasore increased the ratio of Wnt activity before versus after treatment from 0.57 to 0.70 (Fig. S4B), a similar result to the difference in Wnt signaling between ISF-treated and non-treated cells. Likewise, with DN dynamin-1 expression, the ratio of Wnt activity of LEC30 to that of Pro-5 cells increased from approximately 18% to ~100%, suggesting that near full rescue of N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation-induced inhibition of Wnt signaling was achieved (Fig. S4C). A similar trend was also observed for ISF-treated Pro-5 cells (Fig. S4D).

Wnt signaling inhibition caused by LacNAc fucosylation is reversed by free Fuc

The observations presented in the preceding figures provide evidence that increasing N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation of cell surface glycoproteins including LRP6 (Figs. S1A and S5C) leads to inhibition of Wnt signaling due to endocytosis of LRP6 (Fig. 4), predict the existence of a cell surface, Fuc-binding, endocytic receptor (Fig. 5A). We therefore investigated whether adding free Fuc to the culture medium could specifically reverse Wnt signaling inhibition induced by ISF. This experiment was based on the premise that fucosylated LacNAc on the N-glycans of LRP6, and bound by a putative Fuc-specific receptor, would be released by competing free Fuc, thereby allowing N-glycan-fucosylated LRP6 to escape endocytosis, and remain at the cell surface to promote Wnt signaling. L-Fuc monosaccharaide and three control monosaccharides of highly related structure (D-galactose (Gal), D-glucose (Glc) and D-mannose (Man)), were used as competitors. We compared Wnt signaling in cells that were treated, or not, by ISF in the presence of each sugar. In Pro-5 (Fig. 5C) and Lec2 (Fig. S5A) cells, the addition of free Fuc but not control monosaccharides reversed ISF-induced inhibition of Wnt signaling. A dose-dependent effect was observed and maximal competition occurred with 750 μM Fuc (Fig. 5D). Likewise, in highly-fucosylated LEC30 cells, enhanced Wnt signaling activity was observed following the addition of free Fuc, but not the control monosacharrides (Fig. S5B). Not surprisingly, free Fuc did not block ISF from elevating cell-surface fucosylation (Fig. S5C top panel) or LRP6 fucosylation, as confirmed by co-immunoprecipitaiton (Fig. S5C). Moreover, competition by free Fuc prevented the reduction of cell-surface LRP6 due to endocytosis (Fig. S5D).

Figure 5.

Free Fuc suppresses ISF-induced Wnt inhibition.

(A) Diagram summarizing our new findings and predicting the presence of a Fuc-binding receptor. Increasing cell-surface N-glycan LacNAc α(1–3)-fucosylation via ISF-treatment exacerbates the endocytosis of the lipid-raft localized Wnt-receptor LRP6 which, in turn, leads to reduced Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The majority of endocytosed cell-surface LRP6 enters the recycling pathway rather than the degradation pathway following endocytosis induced by ISF treatment. (B) The chemical structure of four monosaccharaides in a vertebrate N-glycan, including L-fucose (Fuc), D-glucose (Glc), D-galactose (Gal) and D-mannose (Man). (C, D) Wnt signaling activity in Pro-5 cells treated by ISF or FucT only, in the presence or absence of a free monosaccharaide. The bars represent standard error of three biological replicates. * unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test p<0.05; ** unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test p<0.01; NS, not significant.

To further explore roles for N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation in endocytosis, we compared the internalization of LacNAc disaccharide with its α1–3-fucosylated counterpart, termed Lewis X (LeX). We prepared Cy-3 tagged LacNAc or LeX by conjugating Cy3 to the reducing end of LacNAc and LeX, respectively (Fig. S6A and S6B). After incubation of Pro-5 and LEC30 cells with these Cy3-tagged glycans, significantly higher amounts of Cy3-labeled LeX were internalized compared to Cy3-labeled LacNAc (Fig. S6C), as expected if a Fuc-binding endocytic receptor was functional. This phenomenon became more obvious at higher glycan concentrations. When 50 μM of each glycan was used, 20–40 fold more LeX was internalized compared to LacNAc, consistent with uptake of LeX by a fucose binding receptor. Moreover, internalization was greater in Pro-5 cells than in LEC30 cells, presumably because the LeX units that terminate complex N-glycans of cell surface glycoproteins in LEC30 cell were already occupying the putative fucose receptor which could not bind to LeX. Finally, externally added, free Fuc partially decreased LeX internalization, but not the internalization of unfucosylated LacNAc (Fig. S6C). Thus, when Pro-5 cells were incubated with 50 μM of LeX-Cy3 together with 1 mM free Fuc, the internalization of LeX-Cy3 was reduced by half (Fig. S6C). Cell-surface ISF treatment, by adding Fuc to complex N-glycans and thereby occupying the putative Fuc binding receptor, also reduced LeX-Cy3 internalization (Fig. S6D and S6E). Together, these results provide strong evidence for the existence of a Fuc-binding receptor at the CHO cell surface, that is involved in the turnover of fucosylated glycoconjugates such as ISF-treated LRP6 (Fig. S6D and S6E).

N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling in breast cancer cells

Since Wnt/β-catenin is hyperactivated in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), which is believed to promote cancer progression,(S. Liu et al., 2018) we examined whether ISF would reduce Wnt/ β-catenin signaling in TNBC cells. To this end, the TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells and non-TNBC MCF-7 breast cancer cells were treated, or not, with ISF. Cellular β-catenin levels were probed by Western blot. As expected, after ISF treatment, a significant decrease of the β-catenin level was detected in MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 6A). Because the phosphorylation of LRP6 is required for the recruitment of Axin to LRP6, which in turn stabilizes β-catenin, we further examined if ISF had any influence on the LRP6 phosphorylation. We immunoprecipitated LRP6 from ISF-treated MDA-MB-231 cells and detected a substantial decrease of LRP6-phosphorylation (Fig. 6B). In line with the4 above observations, wound healing assays confirmed that the ISF treatment also impaired the migration of MDA-MB-231 cancer cells (Fig. 6C and 6F). Similarly, a significant decrease of the β-catenin level and cell-migration were detected in MCF-7 cancer cells (Fig. 6D-F)

Figure 6.

Cell-surface ISF suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling in breast cancer cells.

(A) Time-dependent decrease of the β-catenin level in ISF-treated MDA-MB-231. Western blot of anti-β-catenin (upper panel) and anti-actin (lower panel). (B) Immunoprecipitation of LRP6 from indicated MDA-MB-231 cells and detection of LRP6 and phosphorylated LRP6 by immunoblot. ISF-dependent decrease of LRP-6 phosphorylation. (C) Wound healing assay results from MDA-MB-231 cells treated with ISF or not. (D) Time-dependent decrease of the β-catenin level in ISF-treated MCF-7. (E) Wound healing of MCF-7 cells treated with ISF or not. (F) Time-dependent gap closure of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells treated with ISF or not, in wound healing assays. * one-way ANOVA p<0.05; ** one-way ANOVA p<0.01. In figure A, B and D, the number indicates the relative protein level normalized to corresponding level of actin.

Discussion

Here we report the discovery that increasing cell surface N-glycan LacNAc α1–3-fucosylation exacerbates the endocytosis of lipid-raft localized WNT-receptor LRP6, which in turn suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 5A). Our results also suggest that the majority of internalized cell surface LRP6 enters the recycling pathway rather than the degradation pathway following endocytosis induced by ISF treatment. Inhibiting dynamin-mediated endocytosis rescued Wnt/β-catenin signaling by greatly reducing endocytosis. Most interestingly, ISF-induced inhibition of Wnt signaling was completely prevented by the exogenously added, free Fuc, suggesting the possible existence of a fucose receptor that mediates the endocytosis of LRP6 in membrane lipid rafts. Although our discovery suggests that fucose in the extracellular milieu, and N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation mediated by Golgi fucosyltransferases and GDP-Fuc, may serve as reciprocal switches to modulate Wnt signaling activity, further experiments are required to identify the putative Fuc-specific receptor and any contribution of other fucosylated membrane proteins after ISF treatment. For the detailed mechanism, the presence of ploy-LacNAc (Galβ1-4GlcNAc)n up to 26 units on CHO cell-surface (North et al., 2010) should also been considered because the addition of fucose on different units may contribute to the binding of Fuc-specific receptors. It is well known that LRP6 in complex with WNT-FZD is regulated by phosphorylation.(Bilic et al., 2007; G. Liu et al., 2003; Nusse and Clevers, 2017; Stamos et al., 2014) Upon phosphorylation by several kinases, the cytoplasmic tail of LRP6 recruits AXIN, a scaffold protein that further supports the formation of the LRP-FZD dimer to promote Wnt signaling. Moreover, endocytosis of WNT-LRP6-FZD complex and recycling of WNT-receptor to the plasma membrane play essential roles in Wnt signaling (Bilic et al., 2007). There are 4 LRP6 pools for Wnt modulation, including newly synthesized LRP6, plasma membrane LRP6 (free or in clusters), endocytosed LRP6, and recycling LRP6. The balance of different pools contributes directly to Wnt signaling. The N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation-mediated rapid LRP6 endocytosis we describe here provides an additional regulatory mechanism for Wnt signaling, and ISF treatment can be used to engineer the LacNAc fucosyaltion of LRP6 on the plasma membrane.

Additionally, Wnt signaling plays a critical role in the etiology of various cancers. For example, aberrant activation of Wnt signaling has been observed in colorectal cancer(Bienz and Clevers, 2000) and other gastrointestinal tract cancers(de Sousa et al., 2011). Inhibiting the Wnt pathway has been validated for therapeutic intervention of colorectal cancer(Munemitsu et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2010) as a few anti-cancer drugs that modulate the Wnt pathway in vivo have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)(Anastas and Moon, 2013). The results from our study suggest there may be potential for using chemo-enzymatic glycan editing(Jiang et al., 2018) (i.e., in situ N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation) in cancer therapeutics in order to modulate Wnt activity in a cancer cell. By exploiting targeted drug delivery approaches or in situ cancer tissue microinjection, fucosyltransferase and GDP-Fuc could be delivered into the tumor microenvironment to induce cell surface N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation and thereby inhibit Wnt signaling in cancer cells. Such an approach may be useful for treating TNBCs, an aggressive form of cancer with unpredictable and poor prognosis due to limited treatment options.

One complicating factor is that LacNAc is widely distributed on many membrane glycoproteins and the protein contents have not been identified yet. The α1–3-linked Fuc added to LacNAc units via ISF may also affect the functions of these proteins(Jiang et al., 2018). To enhance the specificity of ISF glycan editing toward a particular cell-surface glycoprotein, it will be necessary to develop more precise targeting strategies. Inspired by selective desialylation of the tumor cell glycocalyx guided by an antibody that targets HER2, an antigen highly expressed in tumors,(Xiao et al., 2016), we envision that the selective N-glycan LacNAc fucosylation of LRP6 in target cancer cells via a fucosyltransferase-antibody conjugate may ultimately be used to selectively inhibit Wnt signaling in cancer cells.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact:

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Prof. Peng Wu (pengwu@scripps.edu)

Materials Availability:

This study did not generate any unique biological reagents. Synthesis of LeX-Cy3 and related chemicals is detailed within the manuscript

Data and code availability:

This study did not generate any unique datasets or code not available in the manuscript files.

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS AND SUBJECT DETAILS

General methods and materials:

All commercialized chemical reagents utilized in this study were purchased from commercial suppliers, and used without further purification unless noted.

Zebrafish stain and maintenance:

All zebrafish experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Different zebrafish lines (Wnt reporter line and wild type AB line) were maintained under standard conditions, and the embryos were staged by morphological characteristics and hours post fertilization (hpf) as described previously(Tamai et al., 2000). In brief, the adult Wnt reporter line and wild-type AB zebrafish were kept at 28 °C on a 14-h light/10-h dark cycle under standard laboratory conditions. Fertilized embryos were obtained from natural spawning and were maintained in embryo medium (150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM KCl, 1.0 mM CaCl2, 0.37 mM KH2PO4, 0.05 mM Na2HPO4, 2.0 mM MgSO4, 0.71 mM NaHCO3 in deionized water, pH 7.4). For the microinjection, the embryos at the 1–2 cell stage were injected with 2 nL of a solution (0.2 M KCl, and 0.2% phenol red) containing GDP-fucose (10 mM) or GDP-FucAl (10 mM) and Hp1,3FT. After developing to indicated stages, embryos were imaged on an epifluorescence microscope.

Cell line and maintenance:

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells are an epithelial cell line derived from the ovary of the Chinese hamster; CHO Pro-5, Lec2, LEC30, and Lec8 cell lines were cultured as described.(Patnaik and Stanley, 2006; Stanley et al., 1996) Pro-5, Lec2 and Lec8 were obtained from the ATCC and LEC30 from prof. Pamela Stanley. CHO cells cultured in D/F12 (vol:vol=50:50) medium supported with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were obtained from the ATCC and cultured in DMEM high glucose medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. MDA-MB-231 cells are an epithelial cell line derived from the mammary gland/breast of a 51 years female human adult, and MCF-7 cells are an epithelial cell line derived from the mammary gland/breast of a 69 years female human adenocarcinoma patient.

METHOD DETAILS

Synthesis of chemical compounds:

BTTPS(Wang et al., 2011), GDP-fucose(Wang et al., 2009), GDP-6-alkylfucose (GDP-FucAl)(Wang et al., 2009) and LacNAc-ethylazide (LacNAc-N3, Galβ1–4GlcNAc-ethylazide)(Wang et al., 2009) were synthesized as previously reported. The LeX-N3 (Lewis X-ethylazide, Galβ1–4(Fucα1–3)GlcNAc-ethylazide) was prepared from LacNAc-N3 using the enzymatic synthesis as previously reported.(Wang et al., 2009) The LeX-Cy3 was prepard by conjugating LeX-N3 with Al-Cy3 via via copper (I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne [3+2] cycloaddition (CuAAC)(Wang et al., 2011). Briefly, LeX-N3 (5 mM) was dissolved in water/methanol (1:1) containing 5 mM Al-Cy3 (Broadpharm), 0.5 mM CuSO4 (ligand BTTPS and Cu2+ pre-mixture at molar ratio 2:1) and 2.5 mM sodium ascorbate. Similarly, for the synthesis of LacNAc-N3/Al-Cy3 conjugate (LacNAc-Cy3), LacNAc-N3 (5 mM) was solved in water/methanol (1:1) containing 5 mM Al-Cy3 (Broadpharm), 0.5 mM CuSO4 (ligand BTTPS and Cu2+ pre-mixture at molar ratio 2:1) and 2.5 mM sodium ascorbate. CuAAC reactions were maintained in 30 oC with gentle vortex (250 rpm) for 6 hours, and monitored by LC-MS. After quenching with 4 mM bathocuproine disulfonate (BCS), the reaction crude was sujected to P2 size exclusion chromatography to purify the products. The generation of LacNAc-Cy3 and LeX-Cy3 conjugate were further confirmed with high resolution mass spectrometry, and then titrated in live cells.

Zebrafish ISF treatments:

GDP-Fuc and GDP-FucAl were dissolved in nuclease-free water at a concentration of 30 mM as stock solutions. For embryo treatment, about 2–3 nL of GDP-Fuc or GDP-FucAl stock was injected into 4 to 8-cell stage embryo chorions, followed by 2–3 nL 2.5 mg/mL Hpα(1–3)-FucT injection. In control embryos, 2–3 nL 2.5 mg/mL Hpα(1–3)-FucT was injected. After the injection, embryos were kept at 28 °C. The newly created α(1–3)-fucosylation was detected via lectin staining with biotinylated Aleuria Aurantia Lectin (AAL) (1:200, Vector lab B-1395) followed by Streptavidin Alexa Fluor 488 staining (1:10K, Thermo Fisher); The incorporation of FucAl was detected via CuAAC reaction as above described.

PNGase F-based N-glycan releasing:

After ISF treatment with Hp1,3FT and GDP-Fuc-biotin as the donor substrates, the Pro-5 CHO cells were collected, washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and lysed with RIPA buffer (pH 7.4, Scientific Fisher) containing 5 μg/mL DNase 1 and protease inhibitor cocktail. The resultant lysate was further treated with PNGase F to remove the N-glycans as the supplier’s instructed. Then, the resultant samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and biotins on glycoproteins were further probed with anti-biotin western blot.

WNT8a production and treatment:

FLAG-WNT8a was constructed as previous described.(Feng et al., 2014) FLAG-WNT8a was produced in CHO Pro 5 cells through transient transfection and purified from the cell culture supernatant by anti-Flag agarose M2 beads (Sigma-Aldrich). The captured protein was released by 1 mM FLAG peptide and dialyzed to get rid of the free FLAG peptide. The FLAG-WNT8a was concentrated to 1 mg/ml by Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Tubes (EMD Millipore). For treating zebrafish embryos, 2 nL of 1 mg/mL FLAG-WNT8a was injected into the chorion at the 1000-cell stage. For treating CHO and CHO glycosylation mutant cells, a final concentration of 100 ng/mL of FLAG-WNT8a was used.

Wnt reporter GFP quantification:

To measure Wnt activity in live zebrafish embryos, treated embryos were sorted into 96-well plates (one per well). GFP expression quantification was carried out on an Eppendorf Mastercycler® Prosystem (Eppendorf, NY, USA) using the SYBR green fluorescence channel. Data were normalized to the signal detected in negative embryos, and quantitated. Statistical significance was deterimined by two-sided Student t-test.

Cell treatments and TOP-flash assays:

Top-flash assays were performed as reported.(Mao et al., 2002; Mishra et al., 2012) In situ fucosylation (ISF) assays were performed as described.(Zheng et al., 2011) The CHO and their mutant derivatives have endogenous Wnt activity, and the Wnt activity of untreated or FucT only treated cells was set as 100% in the TOP-flash assays. Transfections with TOP-flash assay plasmids(Veeman et al., 2003) or RAB5-RFP, RAB7-RFP,(Vonderheit and Helenius, 2005) FLAG-LRP6, (Liu et al., 2003) dynamin 1, dominant negative dynamin 1 (K44A),(E. Lee and De Camilli, 2002) CA β-catenin(Veeman et al., 2003) were carried out using Polyethylenimine (PEI) as described.(Feng et al., 2014) After a 20 min in situ fucosylation treatment, the cells were washed once with Dulbecco׳s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), before performing the dual luciferase assay. For WNT8a treating, the cells were maintained in DPBS containing WNT8a and 5% FBS for 6 h.

For free sugar treatment, the four different monosaccharaides were prepared in distilled water at 100 mM as stock solution, and used at a final concentration of 1 mM in medium. When treating cells by ISF and sugar at same time, sugars were added directly into ISF buffer, and incubated for 20 min with or without the GDP-fucose and Hpα(1–3)-FucT, before the luciferase assay. CHIR99021 treatment was done as formerly described at the concentrations of 10 and 20 μM for the low and high dose treatment, respectively.(Bennett et al., 2002) Dynasore treatment was performed as previous described, at concentrations of 5 and 10 μM to mimic the partial to full inhibition, respectively.(Macia et al., 2006)

Western blot and immunoprecipitation (IP):

Antibody IP and western blot for FLAG-tagged proteins were performed as described.(Feng et al., 2014) Dilution of antibodies or lectins for western blots were: biotinylated-AAL (1:200, Vector lab B-1395); anti-β catenin (1:1000, Sigma C7207); anti-LRP6 ([1C10] (1:1000, Abcam); and mouse anti-biotin HRP (1:10,000, ). Rabbit anti-actin (1:1000, Sigma A 2066) was used to compare the protein loading in the western blots as described.(Tucker et al., 2008) To analyze the fucosylation of endogenous LRP6, collected cells were washed with DPBS, and lysed with RIPA buffer (Scientific Fisher) containing 5 μg/mL DNase 1 and protease inhibitor cocktail. After taking 3% for the input control, 2 μg anti-LRP6 antibody was added to each sample. After 6-hour incubation in the cold room (4 oC) on a rotator, 5 μL of protein G beads (Genscript) were added to isolate the antibody-LRP6 complexes. Then bound proteins were released by boiling in gel loading buffer. Overall fucosylation was detected by lectin blot using AAL-biotin, followed by avidin-HRP staining. To analyze LRP6 in different cellular locations, cells were seeded in 6-well plate. After 48 hr culture, cells were washed with DPBS (pH7.4, pre-chilled) and kept on ice for another 10 minutes to inhibit endocytosis. Then, 2 mg NHS-biotin (EZ-link) was dissolved in 2 mL chilled DPBS, and 0.33 mL per well was added to cells for 2 hr incubation on a slow shaker in the cold room, or 6 hr without shaking. The treated cells were washed with DPBS, and lysed with RIPA buffer. The lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant contained a mixture proteins of cell membrane and cytosol. Streptavidin-beads were applied to isolate biotin-labeled membrane proteins. Remaining were the cytosolic proteins. The undissolved pellets containing the lipid raft proteins were dissolved with 10% SDS at 50 oC for 3 hr. IP of LRP6 in each fraction was performed as described, with the exception that the lipid raft solution had to be diluted 20 times in DPBS to reduce the SDS concentration. For Western blot, 20% of the IP protein from membrane fraction, 5% from cytosolic fraction, and 50% of the LRP6 proteins from lipid raft fraction were loaded on the gel. Quantification of AAL lectin-blots was done as follows: the membranes were blocked with Western blotting reagent solution (Roche, USA) in PBST, and incubated with FITC-AAL (1:100, Vector lab). AAL binding was scanned using Storm 840 (GE, Healthcare) and quantified using ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence and the quantification of co-localization:

To detect the extracellular domain of LRP6, we expressed FLAG-LRP6 in transfected Pro-5 cells, and the resultant FLAG-LRP6 was detected using anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma F7452). Antibody staining was performed as previously described(Feng et al., 2014) at following antibody dilutions: anti-FLAG 1:200; anti-LRP6 1:300; anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluore 488 1:200; Cholera Toxin Subunit B (Recombinant) and Alexa Fluor® 594 Conjugate (Thermo Fisher C22842) 1:100. Nuclei were stained with 0.5 μg/mL bisBenzimide H33342 trihydrochloride (Hoechst 33342, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) in DPBS overnight. Images were taken using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and projected using ImageJ software. Colocalization was determined and quantitated by ImageJ. Quantifying LRP6 and CTB colocalization was done by ImageJ and Volocity.

Wound healing assay:

MDA-MB-231 or MCF-7 cells were plated onto a CytoSelect 24-Well plate (Cell Biolabs). When cells grew to full confluence, the insertion parts were removed to generated gaps (approximately 9 nm) following the suppler’s instruction. The images were collected via microscope, and analyzed with ImageJ to trace gap closure.

Flow cytometry:

The flow cytometry analysis of CHO cells was performed as previously described.(J. Lee et al., 2002) Specifically, AAL-FITC (1:100) was used to detect overall fucosylation; the total LRP6 staining was performed on fixed and permeabilized cells. The surface LRP6 was stained on fixed cell surface staining. All cells were from the same sample pool.

QUANTIFICATION AND STASTICAL ANALYSIS

The flow cytometry data was analyzed using FlowJo (version, 10.5.3). The fluorescence images, wound healing results and western blot results were quantified with ImageJ (version, 1.52v). The two sided students t-test and one-way ANOVA analysis was performed on GraphPad Prism 7 (version 7.0b).

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REGENTS OR RESOURCES | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, and recombinant enzymes | ||

| Alkyne-Cy3 | Broadpharm Inc | Cat#BP-22527 |

| Azide Alexa Fluore 488 | Thermo Fisher | Cat#A10266 |

| DMEM | GIBICO | Cat#11995065 |

| F12 | GIBICO | Cat#31765035 |

| Trypsin/EDTA | GIBICO | Cat#25300054 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | GIBICO | Cat#15140122 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | GIBICO | Cat#F4135 |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#904759 |

| NHS-biotin | EZ-link Thermo Fisher | Cat#20217 |

| dynasore | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#D7693 |

| CHIR99021 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#SML1046 |

| fucose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F2252 |

| galactose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#G0750 |

| glucose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#G7021 |

| mannose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#M6020 |

| LacNAc-N3 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#SMB00412 |

| CuSO4.5H2O | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C8027 |

| Sodium ascorbate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A4034 |

| Bathocuproine disulfonate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#146625–1G |

| Streptavidin Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher | Cat#S11223 |

| bisbenzimide H33342 trihydrochloride (Hoechst 33342) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#B2261 |

| DNase 1 | NEB | Cat#M0303S |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P8340 |

| PNGase F | NEB | Cat#P0704S |

| Anti-FLAG agarose M2 Beads | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#M8823 |

| Protein G beads | GenScript | Cat#L00673 |

| Antibodies and lectins | ||

| Biotinylated aleuria aurantia Lectin | Vector | Cat#B-1395 |

| aleuria aurantia lectin FITC | Vector | Cat#FL-1391–1 |

| Anti-FLAG | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F7452 |

| Rabbit anti-actin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A2066 |

| Anti-LRP6 [1C10] | Abcam | Cat#Ab75358 |

| Anti-β-catenin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C7207 |

| Mouse anti-biotin HRP | Thermo Fisher | Cat#03–3720 |

| Anti-mose IgG Alexa Fluor 488 | Abcam | Cat#Ab150113 |

| Cholera toxin subunit B and Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate | Thermo Fisher | Cat#C22842 |

| Experimental cell lines | ||

| CHO Pro-5 cells | ATCC | Cat#CRL-1781 |

| CHO Lec2 cells | ATCC | Cat#CRL-1736 |

| CHO Lec8 cells | ATCC | Cat#CRL-1737 |

| CHO LEC30 cells | (Patnaik and Stanley, 2006) | N/A |

| MDA-MB-231 (female, 51, human) | ATCC | Cat#HTB-26 |

| MCF-7 (female, 69, human) | ATCC | Cat#HTB-22 |

Significance:

The role of glycosylation in modulating specific signaling pathways is elusive. We discover that elevating cell-surface α(1–3)-fucosylation reduces Wnt/β-catenin signaling in live cells and zebrafish embryos via augmenting the endocytosis of Wnt-coreceptor LRP6. The suppressed Wnt activity induced by α(1–3)-fucosylation is fully reversed by free fucose that is exogenously added. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is upregulated in diseases such as triple-negative breast cancer, which promotes cancer progression. Strategies for in vivo cancer cell-specific fucosylation may offer a means to suppress aberrant Wnt activities and malignant tumor growth.

Highlights.

Increasing cell-surface α(1–3)-fucosylation suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling

Increased α(1–3)-fucosylation elevates the endocytosis of lipid-raft-localized LRP6

Free fucose rescues the Wnt suppression induced by cell-surface α(1–3)-fucosylation

In Summary.

Hong et al. applied a chemenzymatic glycan editing approach to in situ elevate the live cell-surface α(1–3)-fucosylation. This study revealed that increased α(1–3)-fucosylation increases the endocytosis of lipid-raft-localized LRP6, which in turn results the decrease of LRP6-mediated Wnt signaling.

Acknowledgment:

This work was supported by Grants NIH (GM093282 and GM113046 to P. W.; GM105399 to P. S.) and partial support was provided by the NCI Cancer Center grant PO1 13330 (P. S.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: authors have no conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- Anastas JN, Moon RT, 2013. WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 11–26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CN, Ross SE, Longo KA, Bajnok L, Hemati N, Johnson KW, Harrison SD, MacDougald OA, 2002. Regulation of Wnt signaling during adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem 277, 30998–31004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204527200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz M, Clevers H, 2000. Linking colorectal cancer to Wnt signaling. Cell 103, 311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilic J, Huang YL, Davidson G, Zimmermann T, Cruciat C-M, Bienz M, Niehrs C, 2007. Wnt induces LRP6 signalosomes and promotes dishevelled-dependent LRP6 phosphorylation. Science 316, 1619–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1137065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, 2006. Lipid rafts, detergent-resistant membranes, and raft targeting signals. Physiology (Bethesda) 21, 430–439. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00032.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H, Nusse R, 2012. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 149, 1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa EMF, Vermeulen L, Richel D, Medema JP, 2011. Targeting Wnt signaling in colon cancer stem cells. Clin. Cancer Res 17, 647–653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher SL, Hirschberg CB, 1986. Mechanism of galactosylation in the Golgi apparatus. A Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant deficient in translocation of UDP-galactose across Golgi vesicle membranes. J. Biol. Chem 261, 96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher SL, Nuwayhid N, Stanley P, Briles EI, Hirschberg CB, 1984. Translocation across Golgi vesicle membranes: a CHO glycosylation mutant deficient in CMP-sialic acid transport. Cell 39, 295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt M, Gotza B, Gerardy-Schahn R, 1998. Mutants of the CMP-sialic acid transporter causing the Lec2 phenotype. J. Biol. Chem 273, 20189–20195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekany K, Yamanaka Y, Leung T, Sirotkin HI, Topczewski J, Gates MA, Hibi M, Renucci A, Stemple D, Radbill A, Schier AF, Driever W, Hirano T, Talbot WS, Solnica-Krezel L, 1999. The zebrafish bozozok locus encodes Dharma, a homeodomain protein essential for induction of gastrula organizer and dorsoanterior embryonic structures. Development 126, 1427–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Jiang H, Wu P, Marlow FL, 2014. Negative feedback regulation of Wnt signaling via N-linked fucosylation in zebrafish. Developmental Biology 395, 268–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda CY, Waghray D, Levin AM, Thomas C, Garcia KC, 2012. Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled. Science 337, 59–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1222879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes PW, Ley SC, Magee AI, 1999. Aggregation of lipid rafts accompanies signaling via the T cell antigen receptor. J. Cell Biol 147, 447–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, López-Aguilar A, Meng L, Gao Z, Liu Y, Tian X, Yu G, Ben Ovryn, Moremen KW, Wu P, 2018. Modulating Cell-Surface Receptor Signaling and Ion Channel Functions by In Situ Glycan Editing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 57, 967–971. 10.1002/anie.201706535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Lee SK, Jho EH, 2011. Mest/Peg1 inhibits Wnt signalling through regulation of LRP6 glycosylation. Biochem. J 436, 263–269. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawar ZS, Haslam SM, Morris HR, Dell A, Cummings RD, 2005. Novel Poly-GalNAcβ1–4GlcNAc (LacdiNAc) and Fucosylated Poly-LacdiNAc N-Glycans from Mammalian Cells Expressing β1,4- N-Acetylgalactosaminyltransferase and α1,3-Fucosyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem 280, 12810–12819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414273200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C, Chin AJ, Leatherman JL, Kozlowski DJ, Weinberg ES, 2000. Maternally controlled (beta)-catenin-mediated signaling is required for organizer formation in the zebrafish. Development 127, 3899–3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Z, Vijayakumar S, la Torre de, T.V., Rotolo S, Bafico A, 2007. Analysis of endogenous LRP6 function reveals a novel feedback mechanism by which Wnt negatively regulates its receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol 27, 7291–7301. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00773-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF, 1995. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn 203, 253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon YG, Mullins MC, 2011. Maternal and zygotic control of zebrafish dorsoventral axial patterning. Annu. Rev. Genet 45, 357–377. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, De Camilli P, 2002. Dynamin at actin tails. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 99, 161–166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012607799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Park S-H, Stanley P, 2002. Antibodies that recognize bisected complex N-glycans on cell surface glycoproteins can be made in mice lacking N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III. Glycoconj J 19, 211–219. doi: 10.1023/A:1024205925263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Bafico A, Harris VK, Aaronson SA, 2003. A novel mechanism for Wnt activation of canonical signaling through the LRP6 receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol 23, 5825–5835. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5825-5835.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Wang Z, Liu Z, Shi S, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Lin H, 2018. miR-221/222 activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling to promote triple-negative breast cancer. J Mol Cell Biol 10, 302–315. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjy041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YC, Yen HY, Chen CY, Chen CH, Cheng PF, Juan YH, Chen CH, Khoo KH, Yu CJ, Yang PC, Hsu TL, Wong CH, 2011. Sialylation and fucosylation of epidermal growth factor receptor suppress its dimerization and activation in lung cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108, 11332–11337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107385108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T, 2006. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev. Cell 10, 839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao B, Wu W, Li Y, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C, 2001. LDL-receptor-related protein 6 is a receptor for Dickkopf proteins. Nature 411, 321–325. doi: 10.1038/35077108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra SK, Funair L, Cressley A, Gittes GK, Burns RC, 2012. High-affinity Dkk1 receptor Kremen1 is internalized by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. PLoS ONE 7, e52190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro E, Vettori A, Porazzi P, Schiavone M, Rampazzo E, Casari A, Ek O, Facchinello N, Astone M, Zancan I, Milanetto M, Tiso N, Argenton F, 2013. Generation and application of signaling pathway reporter lines in zebrafish. Mol. Genet. Genomics 288, 231–242. doi: 10.1007/s00438-013-0750-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munemitsu S, Albert I, Souza B, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P, 1995. Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 92, 3046–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelamegham S, Aoki-Kinoshita K, Bolton E, Frank M, Lisacek F, Lutteke T, O’Boyle N, Packer NH, Stanley P, Toukach P, Varki A, Woods RJ, 2019. Updates to the symbol nomenclature for glycans guidelines. Glycobiology 29(9), 620–624. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwz045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North SJ, Huang HH, Sundaram S, Jang-Lee J, Etienne AT, Trollope A, Chalabi S, Dell A, Stanley P, Haslam SM, 2010. Glycomics profiling of Chinese hamster ovary cell glycosylation mutants reveals N-glycans of a novel size and complexity. J. Biol. Chem 285, 5759–5775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R, Clevers H, 2017. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell 169, 985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelmann S, Stanley P, Gerardy-Schahn R, 2001. Point mutations identified in Lec8 Chinese hamster ovary glycosylation mutants that inactivate both the UDP-galactose and CMP-sialic acid transporters. J. Biol. Chem 276, 26291–26300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011124200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özhan G, Sezgin E, Wehner D, Pfister AS, Kühl SJ, Kagermeier-Schenk B, Kühl M, Schwille P, Weidinger G, 2013. Lypd6 enhances Wnt/β-catenin signaling by promoting Lrp6 phosphorylation in raft plasma membrane domains. Dev. Cell 26, 331–345. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik SK, Stanley P, 2006. Lectin-resistant CHO glycosylation mutants. Meth. Enzymol 416, 159–182. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)16011-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik SK, Zhang A, Shi S, Stanley P, 2000. alpha(1,3)fucosyltransferases expressed by the gain-of-function Chinese hamster ovary glycosylation mutants LEC12, LEC29, and LEC30. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 375, 322–332. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin B, Stanley P, 1991. Activation of two new alpha(1,3)fucosyltransferase activities in Chinese hamster ovary cells by 5-azacytidine. Cell Regul. 2, 989–1000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.12.989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schier AF, Talbot WS, 2005. Molecular genetics of axis formation in zebrafish. Annu. Rev. Genet 39, 561–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu N, Kawakami K, Ishitani T, 2012. Visualization and exploration of Tcf/Lef function using a highly responsive Wnt/beta-catenin signaling-reporter transgenic zebrafish. Developmental Biology 370, 71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamos JL, Chu MLH, Enos MD, Shah N, Weis WI, 2014. Structural basis of GSK-3 inhibition by N-terminal phosphorylation and by the Wnt receptor LRP6. Elife 3, e01998. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley P, 1981. Selection of specific wheat germ agglutinin-resistant (WgaR) phenotypes from Chinese hamster ovary cell populations containing numerous lecR genotypes. Mol. Cell. Biol 1, 687–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley P, Caillibot V, Siminovitch L, 1975. Selection and characterization of eight phenotypically distinct lines of lectin-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cell. Cell 6, 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley P, Raju TS, Bhaumik M, 1996. CHO cells provide access to novel N-glycans and developmentally regulated glycosyltransferases. Glycobiology 6, 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley P, Siminovitch L, 1977. Complementation between mutants of CHO cells resistant to a variety of plant lectins. Somatic Cell Genet. 3, 391–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint-Jeannet JP, He X, 2000. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature 407, 530–535. doi: 10.1038/35035117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Mintzer KA, Mullins MC, 2008. The BMP signaling gradient patterns dorsoventral tissues in a temporally progressive manner along the anteroposterior axis. Dev. Cell 14, 108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich O, Reinsch S, Urbé S, Zerial M, Parton RG, 1996. Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome. J. Cell Biol 135, 913–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Stanley P, Hart GW, Aebi M, Darvill AG, Kinoshita T, Packer NH, Prestegard JH, Schnaar RL, Seeberger PH, Liu J, Widmalm G, 2015. Oligosaccharides and Polysaccharides. doi: 10.1101/glycobiology.3e.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney S, Stanley P, 2018. Multiple roles for O-glycans in Notch signalling. FEBS Letters 592, 3819–3834. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeman MT, Slusarski DC, Kaykas A, Louie SH, Moon RT, 2003. Zebrafish prickle, a modulator of noncanonical Wnt/Fz signaling, regulates gastrulation movements. Curr. Biol 13, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonderheit A, Helenius A, 2005. Rab7 associates with early endosomes to mediate sorting and transport of Semliki forest virus to late endosomes. PLoS Biol. 3, e233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Hong S, Tran A, Jiang H, Triano R, Liu Y, Chen X, Wu P, 2011. Sulfated ligands for the copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition. Chem. Asian J 6, 2796–2802. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Hu T, Frantom PA, Zheng T, Gerwe B, del Amo DS, Garret S, Seidel RD, Wu P, 2009. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of GDP-L-fucose and the Lewis X glycan derivatives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 106, 16096–16101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908248106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh MG (Ed.), 2016. Lipid Signaling Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology, Methods in Molecular Biology. Springer; New York, New York, NY. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3170-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T, Köster R, 2013. Genetic tools for multicolor imaging in zebrafish larvae. Methods 62, 279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Woods EC, Vukojicic P, Bertozzi CR, 2016. Precision glycocalyx editing as a strategy for cancer immunotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 113, 10304–10309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608069113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Komekado H, Kikuchi A, 2006. Caveolin is necessary for Wnt-3a-dependent internalization of LRP6 and accumulation of beta-catenin. Dev. Cell 11, 213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Sakane H, Yamamoto H, Michiue T, Kikuchi A, 2008. Wnt3a and Dkk1 regulate distinct internalization pathways of LRP6 to tune the activation of beta-catenin signaling. Dev. Cell 15, 37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Ren X, Alt E, Bai X, Huang S, Xu Z, Lynch PM, Moyer MP, Wen X-F, Wu X, 2010. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer by targeting APC-deficient cells for apoptosis. Nature 464, 1058–1061. doi: 10.1038/nature08871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng T, Jiang H, Gros M, del Amo DS, Sundaram S, Lauvau G, Marlow F, Liu Y, Stanley P, Wu P, 2011. Tracking N-acetyllactosamine on cell-surface glycans in vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 50, 4113–4118. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate any unique datasets or code not available in the manuscript files.