Abstract

Although evidence-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), such as Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), have been developed and widely disseminated, the rate of veterans engaging in and completing these therapies is low. Alternative methods of delivery may be needed to help overcome key barriers to treatment. Delivering evidence-based therapies intensively may address practical barriers to treatment attendance as well as problems with avoidance. This report details the case of a combat veteran who received 10 sessions of Cognitive Processing Therapy delivered twice per day over a single, five-day work week (CPT-5). Post-treatment, the veteran reported large and clinically meaningful decreases in PTSD and depression symptom severity as well as in guilt cognitions, which is a purported mechanism of successful treatment. These effects persisted six weeks after treatment ended. Despite the intensive nature of the treatment, the veteran found CPT-5 tolerable and could cite many benefits to completing therapy in one work week. In conclusion, CPT-5 holds promise as a way to efficiently deliver an evidence-based therapy that is both clinically effective and acceptable to patients, although more rigorous clinical trials are needed to test this treatment delivery format.

Keywords: Cognitive Processing Therapy, Brief Therapy, Intensive Treatment, PTSD, Veterans

Despite the existence of evidence-based treatments for PTSD, such as Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2016), a large proportion of veterans either decide not to initiate these treatments or terminate treatment before receiving therapeutic benefit (Imel, Laska, Jakupcak, & Simpson, 2013; Kehle-Forbes, Meis, Spoont, & Polusny, 2016; Shiner et al., 2013). The penetration of evidence-based PTSD treatment into practice is minimal. The percentage of veterans receiving evidence-based therapies for PTSD in specialty clinics within the VA ranges from 6–13% (Sayer et al., 2017; Shiner et al., 2013). Of those veterans who do receive an evidence-based treatment for PTSD, many do not receive an adequate dose of at least five sessions. Kehle-Forbes and colleagues (2016) found that 38% of veterans enrolled in a specialty PTSD clinic drop out of treatment before the fifth session, and up to 25% drop out before the third session. Logistical barriers, such as not being able to take time away from other responsibilities (e.g., work, family) to regularly attend sessions, have been identified as significant barriers to receiving treatment (Stecker, Shiner, Watts, Jones, & Conner, 2013). Novel service delivery methods are needed so that veterans with PTSD can receive adequate treatment doses in a timely fashion.

There is emerging interest in offering evidence-based treatment intensively over the course of 2–3 weeks in order to circumvent logistical barriers to attending treatment and to achieve rapid, clinically significant symptom reduction (Harvey et al., 2017). One such approach is to offer evidence-based treatment in the context of an intensive treatment program (ITP). In ITPs, evidence-based treatments are delivered daily, alongside other adjunctive services intended to facilitate recovery from PTSD (Beidel, Frueh, Neer, & Lejuez, 2017; Harvey et al., 2017; Held et al., 2018; Zalta et al., 2018). Completion rates of ITPs appear to be much higher than those commonly associated with traditionally-delivered evidence-based treatments. Research suggests that between 91–95% of individuals who started an ITP complete treatment (Beidel et al., 2017; Harvey et al., 2017; Held et al., 2018; Zalta et al., 2018). Despite being a promising alternative to traditional outpatient PTSD treatment, which is commonly delivered once per week over the course of several weeks or months, ITPs may not be feasible for individual providers in clinical practice due to their comprehensiveness and cost. Specifically, ITPs tend to involve individuals traveling to and being housed at or near treatment facilities for the duration of treatment. Additionally, ITP staff commonly consists of multiple providers who deliver the different treatment components (e.g., individual therapy, group therapy, mindfulness groups, yoga and other treatment wellness services). Thus, ITPs may not be feasible for wider adoption by individual providers, and may be limited to specialized programs that have the necessary staffing and financial means for such comprehensive programs.

Delivering PTSD treatment intensively over short periods of time without adjunctive services could lead to reduced treatment cost and increased adoption without compromising clinical outcomes, though evidence is currently limited. Foa and colleagues (2018) demonstrated that Prolonged Exposure delivered over two weeks without adjunctive services was noninferior to Prolonged Exposure delivered traditionally over the course of 8 weeks. To date, only a single study has examined week-long primarily cognitively-based PTSD treatment (Ehlers et al., 2010, 2014). Although the study did not utilize CPT, the similar intensive cognitive intervention used in the study produced large reductions in PTSD symptoms that were equivalent to those reported when the intervention was delivered once per week over the course of 12 weeks. Moreover, the intensive intervention in this study was delivered over the course of 7 days, with 2–3 daily sessions that lasted 90–120 minutes each (Ehlers et al., 2014). No published study has yet examined whether CPT can be condensed into a 5-day intensive treatment while maintaining its acceptability, tolerability, and effectiveness. In this manuscript, using the detailed case example of Ben (pseudonym), we describe how CPT can be delivered intensively over a 5 day work week (hereafter referred to as CPT-5).

Adapting Cognitive Processing Therapy for Delivery in a Single Week

Typical course of CPT:

CPT was developed as a 12-session protocol, with weekly 45- to 60-minute individual sessions (Resick et al., 2016). CPT is based in social cognitive theory and targets individuals’ maladaptive beliefs about traumatic events, which are referred to as “stuck points” (Resick et al., 2016). Social cognitive theory suggests that there are three possible ways in which individuals incorporate information about their trauma into their existing mental frameworks. Beliefs may be assimilated when information about the trauma is altered to fit their existing schemata, accommodated when existing schemata are altered to incorporating new information about the trauma, or over-accommodated when existing beliefs are changed to completely match information about the trauma (Resick et al., 2016). Assimilated and over-accommodated beliefs, labeled “stuck points,” are thought to contribute to the development and maintenance of PTSD. Sessions 1–3 are focused on orienting patients to CPT, explaining cognitive theory, and the identification of stuck points. Therapists often begin gently challenging stuck points as early as Session 2, depending on the readiness of the client. Sessions 4–7 focus on cognitive restructuring, and specifically target assimilated stuck points related to the identified index trauma. Over the course of treatment patients progressively learn how to challenge their stuck points through the use of worksheets and homework assigned during each session. Sessions 8–12 are themed sessions that focus on issues of Safety, Trust, Power/Control, Esteem, and Intimacy, which are areas known to be affected by the experience of trauma (Resick et al., 2016). The themed sessions tend to focus on over-accommodated stuck points that are often triggered by everyday situations. Each theme is typically the focus of an entire session (Resick et al., 2016). The final CPT session involves a discussion about what clients have learned during treatment, how the clients’ views about the trauma and the areas of Safety, Trust, Power/Control, Esteem, and Intimacy have changed, as well as a conversation about ways they can maintain their progress in the future.

CPT-5 Rationale:

To allow for maximum feasibility in providers’ and clients’ schedules, our goal was to determine whether CPT can be delivered in a 5-day work week using two 50-minute sessions per day. In practice, CPT is often effectively delivered in fewer than twelve sessions, and research has shown that many individuals fall below the diagnostic threshold for PTSD prior to completing the entire twelve session protocol (Galovski, Blain, Mott, Elwood, & Houle, 2012). Moreover, other evidence-based PTSD treatments, such as Prolonged Exposure (Foa et al., 2018) and Cognitive Therapy for PTSD (Ehlers et al., 2014), have also been shown to be effective when delivered in a shorter amount of time. Structuring treatment around two, daily 50-minute sessions may be feasible for therapists in that they have time to attend to other clinical responsibilities during the work day. This structure also allows clients sufficient time to attend to work or family obligations before or after completing sessions. The goal was to adapt traditionally-delivered CPT as little as possible to maintain good clinical outcomes while allowing for rapid delivery of the treatment. We attempted to make it as easy as possible for clinicians already trained in CPT to adopt this intensive delivery format without needing to learn an additional protocol.

Overall CPT-5 Structure and Session Content:

Each day, the client received two 50-minute CPT sessions for a total of 10 sessions. The client chose morning appointments, and sessions were provided from 8:00–8:50am and 10:00–10:50am. Aside from brief smoking breaks, the client decided to stay in the waiting room during the hour-long break and complete the assigned homework.

The clinician who provided CPT-5 was a doctoral-level, licensed psychologist, who had significant experience delivering the intervention and is a rostered CPT provider. All sessions were audio recorded; a portion of the audio recordings were evaluated by a licensed psychologist, who is also a rostered CPT clinician, to ensure that the required session elements specified in the CPT Therapist Adherence and Competence Protocol (Macdonald, Wiltsey Stirman, Wachen, & Resick, 2014) were covered. CPT-5 was delivered with fidelity to the CPT protocol and followed the variable-length treatment approach to cover all materials in the predetermined 10 sessions. In a slight deviation from the protocol, the client was provided with all materials of the themed sessions on Safety, Trust, Power/Control, Esteem, and Intimacy in Session 7. Due to the predetermined limited number of sessions, the client was instructed to read through all of these materials for homework and identify themes and related stuck points that affected him the most. Priority during all sessions was given to assimilated stuck points related to the index trauma that the client still perceived as distressing and, once these stuck points were sufficiently addressed, the client had an opportunity to transition to other, distressing traumatic events (Farmer, Mitchell, Parker-Guilbert, & Galovski, 2017). Over-accommodated stuck points related to the themes of Safety, Trust, Power/Control, Esteem, and Intimacy were addressed in session when time permitted and as part of the out of session practice assignments (Galovski et al., 2012). In Ben’s case, stuck points related to Safety and Trust were addressed in session as he identified beliefs in these areas as the main barrier to his ability to function in life. Stuck points related to other themes were assigned for homework and briefly reviewed at the beginning of the following sessions.

CPT-5 Homework:

Homework has been shown to be an important part of CPT (Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2018). To allow the client sufficient time to complete homework assignments, a one-hour-long break was scheduled between sessions. In addition, the client was also instructed to complete out of session practice assignments at home before the next day. The therapist did not provide any guidance to the client on how to spend the rest of the day until the next session. Given that the client was allotted an hour-long break between sessions, we determined that it was reasonable to assign a minimum of three worksheets after each session, although additional worksheets were provided.

Self-Report Assessments:

The client was asked to complete the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers, Litz, et al., 2013) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) every day to assess severity of PTSD and depression symptoms, respectively. The client was instructed to rate his symptom severity for only the past 24 hours. The PCL-5 is comprised of 20 items that mirror DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) criteria for PTSD and each item is rated on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Total scores range from 0–80, with higher numbers indicating greater traumatic stress symptoms. Previous research has established scores of 33 or more as suggestive of a probable diagnosis of PTSD (Bovin et al., 2016; Wortmann et al., 2016). The PHQ-9 is comprised of 9 items that mirror DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) criteria for a Major Depressive Episode. Each item is rated on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Scores on the PHQ-9 range from 0–27, with scores of 13 or more suggesting a probable diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (Beard, Hsu, Rifkin, Busch, & Björgvinsson, 2016). Follow-up assessments comprised of the PCL-5 and PHQ-9 were conducted at one, four, six, and eight weeks following the completion of CPT-5. For the follow-up assessments, the client was instructed to rate his symptom severity for the past week.

In addition to PTSD and depression symptom severity, the client was also asked to complete the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory (TRGI; Kubany et al., 1996; Myers, Wilkins, Allard, & Norman, 2012). The TRGI, which is comprised of 32 items, yields three subscales Global Guilt (e.g., “I experience intense guilt related to what happened”), Distress (e.g., “What happened causes a lot of pain and suffering”), and Guilt Cognitions (e.g., “I was responsible for causing what happened”). The measure has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity as a measure of trauma-related guilt in combat veterans (Kubany et al., 1996). Only Guilt Cognitions were examined during treatment to assist in identifying additional therapy targets (i.e., stuck points). Items are rated on a scale of 1 (not at all true or never true) to 5 (extremely true or always true), and the total possible Guilt Cognition score ranges from 0 to 88. The client was asked to complete the TRGI at baseline, prior to Session 6, and at post-treatment.

Client Selection and Preparation for CPT-5

Prior to starting CPT-5, the client completed a standard clinical intake evaluation at the Road Home Program: Center for Veterans and Their Families at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, IL. The Road Home Program at Rush is a philanthropically-funded program, which offers outpatient and intensive mental health treatment services at no cost to service members, veterans, and their families, regardless of individuals’ service duration and their military discharge status. The intake evaluation entails a thorough clinical interview, a comprehensive self-report assessment battery to assess PTSD, depression, and substance use disorder symptom severity, among others. Because the client presented with symptoms of PTSD, a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (Weathers, Blake, et al., 2013) was conducted to confirm the diagnosis. The total duration of the intake evaluation was approximately three hours. Following the intake evaluation, the client was offered to participate in a 3-week all-day ITP which is heavily based in CPT, although the program’s waitlist at that time would have prevented him from receiving treatment for several months. CPT-5 was offered as an alternative and was presented as an option to initiate trauma-focused therapy immediately. The client was made aware that he would be receiving a well-established evidence-based treatment for PTSD (i.e., CPT) but that the week-long delivery format had not yet been empirically tested. Additionally, the client was informed that participation in CPT-5 would not exclude him from eventual admission to the more comprehensive 3-week ITP or standard outpatient care. The client agreed to receive CPT-5 due to the significant distress he was experiencing and the potential to make substantial treatment gains in a shorter time-frame. CPT-5, like all other treatment services offered at the Road Home Program at Rush University Medical Center was provided at no cost to the veteran.

Client Description

Ben (pseudonym), a 31-year-old infantryman who served in the Army from 2004–2008, endorsed exposure to heavy combat. For the CAPS-5 assessment, Ben focused on a specific index trauma: shooting a non-combatant. Ben met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD based on the CAPS-5 (Total score: 53). During his intake, Ben also reported additional traumatic events included calling in an airstrike on a building with women and children present and witnessing his team leader’s death. Based on through a thorough clinical interview, but not verified via a validated structured diagnostic instrument, Ben also met the diagnostic criteria for recurrent, severe Major Depressive Disorder and Alcohol and Cannabis Use Disorders, both in partial remission. At the time of intake, Ben also reported housing instability, occupational instability, and interpersonal problems. Informed consent and permission to present the case report were obtained from Ben, and the authors disclosed any potential conflicts of interests. All data collection procedures were approved by the Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

One year before starting CPT-5, Ben attempted to initiate treatment for a 3-week ITP focused on PTSD at the Road Home Program at Rush University Medical Center. He withdrew shortly after to complete a court-mandated substance use treatment program to address his Alcohol Use Disorder. Ben reported that he received an exposure-based therapy in the substance use treatment program where “they had me write my trauma down a bunch of times, and asked me how it made me feel” which he did not find useful. Ben returned for services at the Road Home Program approximately12 months later expressing an interest in engaging in trauma-focused treatment and verbalized his belief that current symptoms of depression, anxiety, substance use, housing and occupational instability were most likely related to his reactions to being in combat during his deployments. At this point, Ben’s self-reported PTSD and depression symptom scores were 58 on the PCL-5 and 19 on the PHQ-9, respectively.

Ben was determined to be a good candidate for CPT-5 due to his high level of motivation (“I just want to get something started”), his relative inexperience with evidence-based treatment, and his willingness to attend therapy twice per day for five days. Despite the severity of his distress, Ben was assessed to be at minimal risk as he denied suicidal/homicidal ideation, plan, or intent, current substance dependence, or a history of mania or psychosis.

CPT-5 Treatment Process

Ben attended all 10 CPT-5 sessions, and completed all required out-of-session homework assignments. For CPT-5, Ben selected ‘shooting a civilian’ as his index trauma. Per protocol (Resick et al., 2016), CPT started out by focusing on assimilated stuck points associated with his index trauma. Ben and his therapist worked through several key assimilated stuck points, such as “I should have waited longer [before taking the shot],” “I should have waited for positive identification,” “I should have told the rest of my team to investigate the situation [before taking the shot],” using the CPT worksheets and Socratic dialogue. By Session 4, Ben had a good understanding of the CPT worksheets and built sufficient context to challenge the stuck points with relatively little guidance from his therapist. Having built contextual awareness of the area of operation, negative events that took place in the same area the day prior to the index trauma, and the civilian’s suspicious behaviors allowed him to determine that waiting longer before taking the shot or sending his team to investigate would have likely increased the risk for him and his entire team, and allowed him to effectively challenge his stuck points by Session 4. Although he was able to challenge stuck points on his own early on, Ben’s progress appeared similar to clients with comparable levels of motivation who attend weekly CPT sessions.

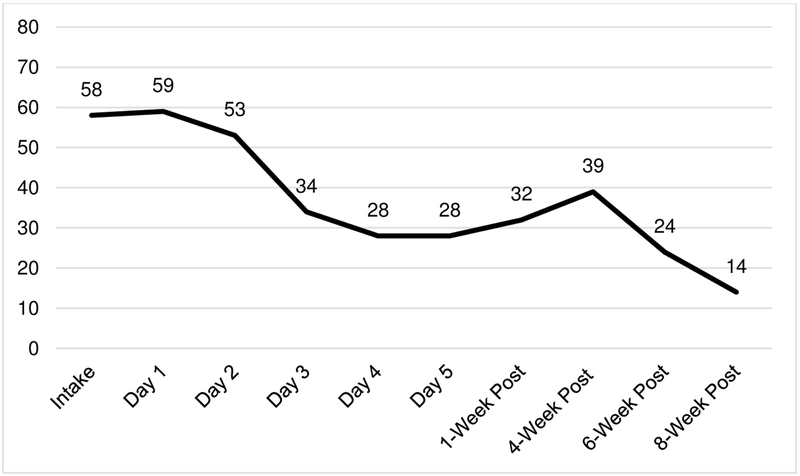

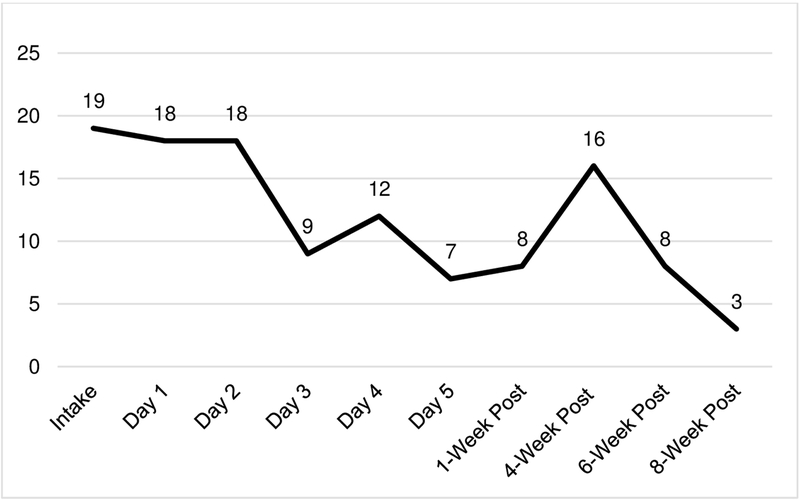

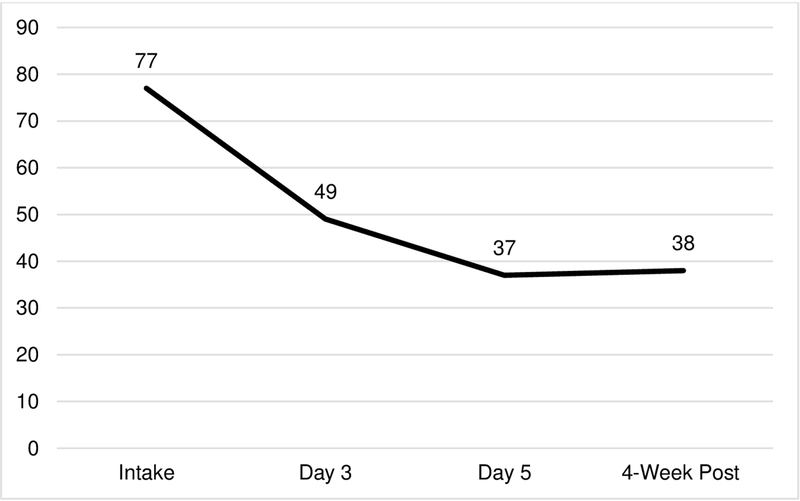

After Session 4, Ben’s PCL-5 and PHQ-9 scores had reduced substantially (PCL-5 reduced from 58 at baseline to 34 after Session 4; PHQ-9 reduced from 19 at baseline to 9 after Session 4; see Figures 1 and 2, respectively). Indeed, the symptom reductions for PTSD and depression were below diagnostic threshold cut-offs for both the PCL-5 and PHQ-9 (Beard et al., 2016; Bovin et al., 2016; Wortmann et al., 2016). This reduction in symptom severity prompted Ben to ask his therapist about the possibility of shifting the focus of treatment to other traumatic events that he had mentioned during the intake assessment, since his beliefs about those events still elicited significant distress. In line with traditional CPT, assimilated stuck points associated with the additional two traumatic events (calling in an airstrike on a building with women and children present and witnessing his team leader’s death) were targeted over the course of two sessions each and were the focus of homework assignments that the veteran completed outside of session. In addition, over-accommodated stuck points associated with his index trauma, such as “I am a monster” and “I don’t deserve good things to happen to me because of what I have done”, were assigned for homework following Session 5 after the TRGI reflected significant reduction in assimilated stuck points (TRGI Cognitions scale reduced from 77 at baseline to 49 after Session 5; see Figure 3).

Figure 1.

PTSD symptom severity by treatment day as measured by the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5.

Figure 2.

Depression symptom severity by treatment day as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Figure 3.

Trauma-related guilt cognitions by treatment day as measured by the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory.

Similar to other individuals who receive CPT, Ben was increasingly able to challenge his remaining stuck points on his own. For the remaining sessions, Ben’s therapist continued by following the CPT session protocol and targeted any remaining assimilated stuck points from Ben’s other two traumatic events. Ben’s therapist used Socratic dialogue to slow down or “deepen” the challenging process whenever it appeared that Ben filled out some of the worksheets without thoroughly thinking through his answers and helped Ben explore how certain patterns of problematic thinking interfered with his functioning in his everyday life.

In Session 7, the five themes of Safety, Trust, Power/Control, Intimacy, and Esteem were introduced, and Ben was provided with the handouts for all of the modules at the end of the session. Providing the client with all modules at once can be considered a deviation from the CPT protocol, as modules are usually introduced after one another (Resick et al., 2016). Given that the CPT-5 protocol was limited to 10 sessions, there was not enough time to spend an entire session on each theme. Therefore, Ben was encouraged to prioritize the themes based on the impact each area had on his life. Ben chose to focus on Safety (remainder of Session 7 and part of Session 8), Trust (Session 8), and Esteem (Session 9 and part of Session 10) and agreed to read through the remaining modules (Power/Control and Intimacy) in between sessions and complete Challenging Beliefs Worksheets on relevant, theme-specific stuck points. Session 9 focused on the Esteem module and involved re-examining previously challenged over-accommodated stuck points, such as “I am worthless” and “I was a terrible Soldier”. Ben was also encouraged to think about potential stuck points related to ending therapy and to target these for homework in addition to re-writing his impact statement. In Session 10, Ben and his therapist reviewed and compared the new and old impact statements, used Challenging Beliefs Worksheets to work through a stuck point relating to his treatment coming to an end (i.e., “I will not be able to maintain the gains I have made in therapy”), and to review Ben’s overall progress over the past week.

Ben’s symptom trajectory was similar to those reported in larger studies of traditional CPT (e.g., Galovski et al., 2012) with symptoms reducing after Session 4 once assimilated stuck points had been sufficiently challenged. Ben’s therapist would have made the same clinical decision to focus on assimilated stuck points associated with additional traumatic events if CPT had been delivered in another format given that Ben reported struggling with those beliefs. There were no adverse events associated with Ben’s treatment using CPT-5. Following the completion of CPT-5, the client was referred back to his original treatment provider (the same one who conducted the assessment prior to starting CPT-5) for continued care as usual in the form of bi-weekly appointments using a CPT-booster approach or general Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. The intent was for Ben to continue to use the skills learned during CPT-5, including the CPT worksheets, and to apply them to different situations that would arise during everyday life.

In his one-week post-CPT-5 appointment, Ben reported that he was “doing well, still,” and his symptom scores reflected his stability one week following treatment (PCL-5 score at 1-week post-treatment: 32; PHQ-9 score at 1-week post-treatment: 8). Ben did not attend his next scheduled follow up appointment two weeks later, and a brief phone call with his original therapist indicated the presence of unexpected psychosocial stressors. This was confirmed during his next scheduled appointment where Ben stated that he had been experiencing interpersonal conflict with his ex-wife which led to a brief period of binge-drinking. When Ben returned to care four weeks following the completion of CPT-5, he had abstained from alcohol for the past week, but his depression symptoms were significantly elevated. Ben stated “I don’t really think about [index trauma] anymore, it’s really more about what’s going on in my life now”. In line with the CPT booster session format, his CPT-5 therapist provided brief psychoeducation on how to utilize the Challenging Belief Worksheets to address non-trauma related stuck points, and assigned new worksheets for current stuck points related to psychosocial stressors. Six weeks following the completion of CPT-5, Ben stated “I feel a lot better. The worksheets really helped me think through things better.” This qualitative self-report was reflected in his lowest PCL-5 score to date (24), and his PHQ-9 score (8) leveled off at his post-CPT-5 score. Eight weeks following the completion of CPT-5, Ben’s PTSD and depression severity continued to decrease (PCL-5 score: 14; PHQ-9 score: 3). Ben reported that he applied and was accepted into a local university’s adult learning program where he planned to pursue his bachelor’s degree. Ben stated that “I’ve tried and failed at this before, but I feel like my head is actually in the right place now”. Additionally, he outlined specific plans to move to a new apartment closer to his school and family and continued to be engaged in an outpatient substance use treatment group on a weekly basis. In reflecting on his progress, Ben laughed, saying “I don’t know what you did to me, but I didn’t think it was possible for me to feel like this again.”

Client Feedback Following CPT-5

Following the conclusion of CPT-5, Ben and his therapist discussed his overall impressions of the intervention, future considerations for improvement, and whether he would recommend this treatment to other veterans. Overall, Ben was highly satisfied with CPT-5.

“I thought it was extremely helpful. I think there’s a lot of people who could benefit from doing it in one week, definitely. I think that, the 12-week, doing 1 session a week is… bullshit, because… you forget half that stuff that you were just taught, you know. And it’s like, [Intensive CPT] gets pounded into you almost for like a week, and it’s hard to forget after that … if you give someone a week to do this, they’ll put it off, put it off…”

Ben emphasized that the daily, intensive nature of CPT-5 had two clear benefits over CPT delivered weekly. First, the intensive nature of CPT-5 helped him overcome his inclination to avoid through not completing homework or not reflecting any further on session content. Second, the frequency of the sessions helped him retain the concepts and skills that were taught.

“This was awesome… It’s all fresh in my mind. If it was just once a week, I would forget everything. I’m one of those people, I have a bad memory, so I’d probably come in and say ‘I have no idea what we talked about last week.’”

Consistent with approaches during traditional CPT, Ben felt that it was helpful to focus on more than a single index trauma during the course of CPT-5 and noted that he felt confident to be able to apply the skills to challenge stuck points that were not directly addressed in treatment. This suggests that the reduction of treatment to one week does not need to restrict clinicians to focus on only a single traumatic event if other experiences are contributing significantly to the distress clients experience.

“I felt, if I’m always focusing on one, these other [traumas] were in the back of my mind constantly, and I wanted to tackle more than one at the same time.” “Given the process [of CPT], I should be able to tackle some of those [stuck points]. Maybe if I wasn’t coming back in to work with [individual provider], I’d want to go over those, but now that I know that if I do have problems with any of those [stuck points] I can come back in and ask questions about them.”

When asked about the format of two daily sessions, Ben reported that being at the treatment facility for no more than three hours allowed him to engage in regular activities (e.g., socializing with his family, running errands, completing CPT assignments, etc.).

“I think [the hour in between sessions] was perfect. Yeah, no more time, that was definitely enough time to finish everything.”

Ben had some suggestions for additional programming that may be helpful. Specifically, though not necessary, Ben thought that adding a minimal group component could facilitate the challenging of stuck points.

“Maybe [adding] one or two group sessions or something, just so you could get some insight. Maybe one or two just to show you’re not alone, show others that there’s others going through it, show there’s others making progress, that it works. […] I’d probably just have everyone read over one Challenging Beliefs Worksheet, and have the rest of the group give insight on it, and just go around the room and have everyone do it once.”

Ben was confident that this intervention would benefit other veterans similarly and highly recommended the intensive intervention.

“I think it’s very helpful, I know a lot of veterans who would benefit from this… You know, in one week… I’m just impressed. I am.”

Conclusion

In this case report, we have shown that that 10 sessions of CPT delivered twice per day over the course of a single week (CPT-5) can be effective in addressing and reducing PTSD and depression symptom severity. Ben’s clinical outcomes resemble findings from larger studies demonstrating that intensively-delivered evidence-based PTSD treatments appear to have the benefit of rapid symptom reduction (Ehlers et al., 2014; Foa et al., 2018). Moreover, Ben’s symptom reduction appeared similar to what has been observed in a more comprehensive 3-week-long CPT-based ITP (Zalta et al., 2018). For example, Ben was able to notice improvements as soon as Session 4 (Day 2), as opposed to during the fourth week during CPT delivered in a traditional format. It is possible that the shift in focus to additional traumatic events resulted in the lack of substantial changes on the PCL-5 from Day 3 to the 1-week post-treatment assessment, as the PCL-5 was anchored on the index trauma. It is also plausible that the client needed more time to notice the impact of the gains he made in the intensive treatment or practice the skills, which is why he did not report additional substantial symptom reductions until after the conclusion of CPT-5. It is noteworthy that Ben achieved meaningful and lasting symptom reduction with approximately nine hours of homework, in contrast to the over 22 hours that is expected of individuals who complete CPT protocols (cf. Resick et al., 2002). Although existing research has demonstrated the importance of homework completion during CPT (cf. Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2018), future research should examine the roles homework quality and quantity play in intensively-delivered CPT.

The condensed delivery format presented in this case report has the potential to make CPT more feasible for patients by removing several barriers, without compromising its clinical effectiveness. Doing so may lead to increased treatment completion rates. Although CPT has amassed substantial evidence as a front-line psychotherapy for PTSD, its adoption into everyday practice has been minimal (Shiner et al., 2013; Stecker et al., 2013). Receiving treatment over the course of several weeks or months may present an insurmountable barrier for some veterans (Stecker et al., 2013). The week-long format of CPT-5 may fit more easily with individuals’ schedules, and as a result, individuals may be more interested in receiving a week-long intervention. It is possible that intensive treatments, like CPT-5, yield higher completion rates compared to evidence-based treatments delivered on a traditional, outpatient basis. From a provider’s perspective, the week-long treatment format may be attractive because, in addition to helping with caseload turnover, delivering a protocol like CPT-5 still allows some time for other clinical responsibilities.

Given his high motivation for treatment and his ability to learn new concepts quickly, it is possible that Ben’s case is unique and that other clients may require additional time in between sessions. Future studies should examine which clients may require additional time for homework and whether the time between daily sessions impacts outcomes. Despite the high satisfaction with the treatment, other issues that are not directly related to PTSD, such as relationship and parenting issues, may require additional treatment following the completion of CPT-5, as was suggested in Ben’s case. Ben’s response to this treatment indicates CPT-5 has the potential to provide rapid relief of PTSD symptoms and provide a strong foundation for continued treatment on secondary presenting concerns. In Ben’s case, receiving booster sessions was important to address some of his non-trauma-related concerns that lead to temporary increases in his distress.

CPT-5 did not eliminate all treatment and implementation barriers and it is important to consider possible barriers and limitations to wider adoption of CPT-5 from the perspectives of both the clients and treatment providers. For example, not every individual will be able to take one week off from work, shift their work schedule, or be away from family and other responsibilities to attend two therapy sessions per day. Moreover, transportation to and from the treatment facility every single day for one week can present financial and logistical barriers. For therapists who typically treat their clients on a weekly basis, a shift to an intensive one-week model may be difficult to arrange. Moreover, the limited availability of therapists trained in evidence-based treatments will also be a limiting factor for the adoption of intensive interventions like CPT-5. At this time, it may be difficult for therapists to get intensive outpatient treatments like CPT-5 reimbursed by insurance companies. Additionally, it is unclear how feasible it is for therapists with less experience delivering CPT to provide such an intensively-delivered treatment and what support, supervision, or consultation may need to be in place in order for less experienced providers to achieve treatment success using intensively-delivered treatments.

Although CPT-5 was effective for Ben, rigorous, larger-scale controlled trials are necessary to determine the acceptability, feasibility, tolerability, and effectiveness of the intervention. If CPT-5 is found to be a well-tolerated and effective intervention, it will also be important to determine which types of clients may particularly benefit from the condensed delivery format as opposed to CPT delivered “as usual” once per week for approximately 12 weeks or CPT delivered as part of other intensive programs. Larger-scale studies are needed to determine dropout rates and the risk for adverse events in intensively-delivered trauma treatments. Future research should examine which types of aftercare services may be needed following the completion of CPT-5. For example, it is possible that after completion of a CPT-5 protocol, individuals may be appropriate for reduced frequency of psychotherapy (e.g. bi-weekly or monthly) as well as a change in therapy approach (e.g. supportive counseling or case management), which may be delivered by therapists without specialized training in evidence-based treatments, though these hypotheses require further empirical testing. Lastly, more comprehensive studies are also needed to help determine if CPT-5 operates through a similar mechanism (i.e., reductions in negative post-trauma cognitions; Zalta, 2015) as CPT delivered as usual, and to determine if the observed treatment effects persist over time.

Being able to effectively deliver evidence-based therapies over the course of a single week has the potential to transform the ways in which PTSD is treated. In addition to being feasible for and possibly preferred by some clients, delivering treatment over a single work week may be an attractive alternative for providers as well. The one-week treatment interval can be adopted to fit into many providers’ schedules. If CPT-5 is found to be safe and effective in larger more rigorous studies, future research should examine potential barriers and facilitators to implementing intensively-delivered treatments into various practice settings and to help address questions related to scheduling and auxiliary training of clinicians, among others.

Highlights:

Cognitive Processing Therapy can be effectively delivered in a single week

CPT-5 can lead to clinically meaningful symptom reductions that persist over time

CPT-5 can be well-tolerated by clients

Some clients may prefer condensed or intensive treatment delivery formats like CPT-5

Larger scale clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of CPT-5 are needed

Acknowledgements

We thank the Wounded Warrior Project for their support of the Warrior Care Network and the resulting research. Philip Held receives grant support from the Boeing Company and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation. Niranjan Karnik receives grant support from Welcome Back Veterans, an initiative of the McCormick Foundation and Major League Baseball; the Bob Woodruff Foundation; and the National Center for Advancing Translational Science of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR002389). Alyson Zalta receives grant support from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH103394). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any funding agencies specified above.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beard C, Hsu KJ, Rifkin LS, Busch AB, & Björgvinsson T (2016). Validation of the PHQ-9 in a psychiatric sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 193, 267–273. 10.1016/j.jad.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Frueh BC, Neer SM, & Lejuez CW (2017). The efficacy of Trauma Management Therapy: A controlled pilot investigation of a three-week intensive outpatient program for combat-related PTSD. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 50, 23–32. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, & Keane TM (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379–1391. 10.1037/pas0000254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM, Hackmann A, Grey N, Liness S, Wild J, … McManus F (2010). Intensive cognitive therapy for PTSD: A feasibility study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 38(4), 383–98. 10.1017/S1352465810000214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Hackmann A, Grey N, Wild J, Liness S, Albert I, … Clark DM (2014). A randomized controlled trial of 7-day intensive and standard weekly cognitive therapy for PTSD and emotion-focused supportive therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3), 294–304. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13040552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer CC, Mitchell KS, Parker-Guilbert K, & Galovski TE (2017). Fidelity to the Cognitive Processing Therapy protocol: Evaluation of critical elements. Behavior Therapy, 48(2), 195–206. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, McLean CP, Zang Y, Rosenfield D, Yadin E, Yarvis JS, … Peterson AL (2018). Effect of prolonged exposure therapy delivered over 2 weeks vs 8 weeks vs present-centered therapy on PTSD symptom severity in military personnel. JAMA, 319(4), 354–364. 10.1001/jama.2017.21242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galovski TE, Blain LM, Mott JM, Elwood L, & Houle T (2012). Manualized therapy for PTSD: flexing the structure of cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 968–81. 10.1037/a0030600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey MM, Rauch SAM, Zalta AK, Sornborger J, Pollack MH, Rothbaum BO, … Simon NM (2017). Intensive treatment models to address posttraumatic stress among post-9/11 warriors: The Warrior Care Network. FOCUS, 15(4), 378–383. 10.1176/appi.focus.20170022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held P, Klassen BJ, Boley RA, Wiltsey Stirman S, Brennan MBA, Pollack MH, … Zalta AK (2018). Feasibility, acceptability, and satisfaction with and intensive outpatient treatment program for service members and veterans with PTSD. Manuscript under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Laska K, Jakupcak M, & Simpson TL (2013). Meta-analysis of dropout in treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 394–404. 10.1037/a0031474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle-Forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont MR, & Polusny MA (2016). Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(1), 107–114. 10.1037/tra0000065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Haynes SN, Abueg FR, Manke FP, Brennan JM, & Stahura C (1996). Development and validation of the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory (TRGI). Psychological Assessment, 8(4), 428–444. 10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald A, Wiltsey Stirman S, Wachen JS, & Resick PA (2014). Cognitive Processing Therapy: Therapist adherence and competence protocol individual version - revised. Retrieved from https://cptforptsd.com/achieving-provider-status/

- Myers US, Wilkins KC, Allard CB, & Norman SB (2012). Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory: Review of psychometrics and directions for future research. In Advances in psychology research (Vol 91). [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Monson CM, & Chard KM (2016). Cognitive processing therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, & Feuer CA (2002). A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 867–879. 10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer NA, Rosen CS, Bernardy NC, Cook JM, Orazem RJ, Chard KM, … Schnurr PP (2017). Context matters: Team and organizational factors associated with reach of evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD in the Veterans Health Administration. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(6), 904–918. 10.1007/s10488-017-0809-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, D’Avolio LW, Nguyen TM, Zayed MH, Young-Xu Y, Desai RA, … Watts BV (2013). Measuring use of evidence based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(4), 311–318. 10.1007/s10488-012-0421-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker T, Shiner B, Watts BV, Jones M, & Conner KR (2013). Treatment-seeking barriers for veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts who screen positive for PTSD. Psychiatric Services, 64(3), 280–283. 10.1176/appi.ps.001372012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, & Keane TM (2013). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). PTSD: National Center for PTSD; Retrieved from www.ptsd.va.gov [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, & Schnurr PP (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). National Center for PTSD. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltsey Stirman S, Gutner CA, Suvak MK, Adler A, Calloway A, & Resick P (2018). Homework completion, patient characteristics, and symptom change in cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 49(5), 741–755. 10.1016/j.beth.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann JH, Jordan AH, Weathers FW, Resick PA, Dondanville KA, Hall-Clark B, … Litz BT (2016). Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1392–1403. 10.1037/pas0000260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalta AK (2015). Psychological mechanisms of effective cognitive–behavioral treatments for PTSD. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(4), 23 10.1007/s11920-015-0560-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalta AK, Held P, Smith DL, Klassen BJ, Lofgreen AM, Normand PS, … Karnik NS (2018). Evaluating patterns and predictors of symptom change during a three-week intensive outpatient treatment for veterans with PTSD. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 242 10.1186/s12888-018-1816-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]