Abstract

Autosomal Recessive Spinocerebellar Ataxia 20, SCAR20, is a rare condition characterized by intellectual disability, lack of speech, ataxia, coarse facies and macrocephaly, caused by SNX14 variants. While all cases described are due to homozygous variants that generally result in loss of protein, so far there are no other cases of reported compound heterozygous variants. Here we describe the first non-consanguineous SCAR20 family, the second Portuguese, with two siblings presenting similar clinical features caused by compound heterozygous SNX14 variants: NM_001350532.1:c.1195C>T, p.(Arg399*) combined with a novel complex genomic rearrangement. Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR), long-range PCR and sequencing was used to elucidate the region and mechanisms involved in the latter: two deletions, an inversion and an AG insertion: NM_001350532.1:c.[612+3028_698-2759del;698-2758_698-516inv;698-515_1171+1366delinsAG]. In silico analyses of these variants are in agreement with causality, enabling a genotype-phenotype correlation in both patients. Clinical phenotype includes dystonia and stereotypies never associated with SCAR20. Overall, this study allowed to extend the knowledge of the phenotypic and mutational spectrum of SCAR20, and to validate the role of Sorting nexin-14 in a well-defined neurodevelopmental syndrome, which can lead to cognitive impairment. We also highlight the value of an accurate clinical evaluation and deep phenotyping to disclose the molecular defect underlying highly heterogeneous condition such as intellectual disability.

Keywords: intellectual disability, Autosomal Recessive Spinocerebellar Ataxia 20, SNX14 gene, cerebellar hypoplasia, exome sequencing, complex genomic rearrangement

Introduction

Autosomal Recessive Spinocerebellar Ataxia 20 (SCAR20, OMIM #616354) was first described in a Portuguese consanguineous family as a disorder characterized by severe ataxia, intellectual disability (ID), lack of speech, coarse facies, macrocephaly, skeletal abnormalities and cerebellar hypotrophy (Sousa et al., 2014). In the same year, Thomas and co-authors identified the Sorting Nexin-14 gene (SNX14), described seven affected patients belonging to two distinct families, including those previously reported by Sousa et al. (2014), and widened the SCAR20 phenotypic spectrum describing seizures and deafness (Thomas et al., 2014). To date, 19 distinct homozygous pathogenic SNX14 variants have been identified, including point mutations and deletions, affecting at least 47 individuals from 25 unrelated consanguineous families (Thomas et al., 2014; Akizu et al., 2015; Jazayeri et al., 2015; Karaca et al., 2015; Shukla et al., 2017; Trujillano et al., 2017; Al-Hashmi et al., 2018; Bryant et al., 2018).

Herein, we describe the first non-consanguineous family with two siblings affected by SCAR20, carrying two SNX14 compound heterozygous variants, of which only one, p.(Arg399*), was identified by exome sequencing. Phenotypic similarity to SCAR20, prompted further characterization of the other allele that subsequently was found to contain a complex genomic rearrangement in SNX14: NM_001350532.1:c.[612+3028_698-2759del;698-2758_698-516inv;698-515_1171+1366delinsAG]. Interestingly, siblings also show dystonia and stereotypies, besides the pathognomonic SCAR20 clinical features, representing the first implication of SNX14 in movement impairment. Further functional studies are warranted to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Report

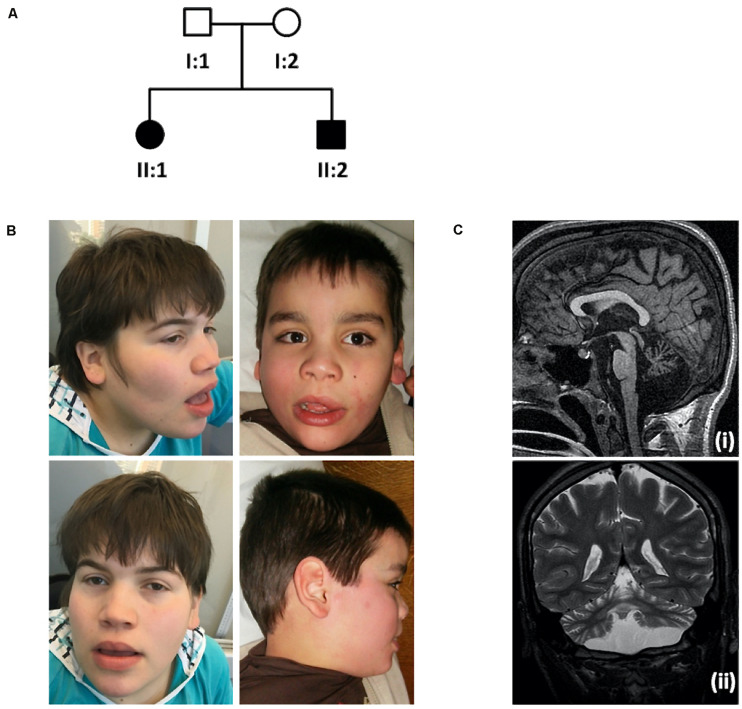

Patient II:1 is the first female child of a healthy non-consanguineous Portuguese couple (Figure 1A). She is currently 29-year-old. She was referred to a pediatric neurology consultation at 2 months for febrile seizures. Family history is negative for neurodevelopmental disorders except for a paternal second-cousin with Prader-Willi syndrome. Gestation and delivery were uneventful except for gestational diabetes at 37 weeks, born at 39 weeks of gestation with weight, 4000 g, length, 51 cm and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC), 36.5 cm. At 9 months she was very hypotonic with no head control; Growth parameters were normal except for OFC. Additional features include diminished reflexes in the lower limbs, bilateral talipes equinovarus with a dystonic hallux, kyphosis, neurosensorial hearing loss, macrocephaly, and facial dysmorphisms: high forehead, hypertelorism, depressed nasal bridge, large base to nose, anteverted nares and thick lips (Figure 1B). She never acquired independent walking or speech and severe intellectual disability was evident. Although speechless she communicates with the eyes and hands. She also had frequent dystonic manual stereotypies with hands apart.

FIGURE 1.

Family pedigree, pictures showing craniofacial features and brain MRI scan. (A) Family pedigree. (B) Photographs of the index case (II:1, left), at 18-year-old, showing macrocephaly, high forehead, hypertelorism, depressed nasal bridge, large base to nose, anteverted nares and thick lips and younger brother (II:2, right), at 8-year-old, presenting with similar phenotypic features. (C) Brain MRI scan from patient II:2: Sagittal T1 SPGR (i) and coronal T2-weighted (ii) images showing diffuse cerebellar atrophy, involving both the vermis and the hemispheres, as well as pontine atrophy. There is no evidence of dentate calcification. Brain MRI form patient II:1 showed overlapping abnormalities.

The male patient II:2, currently 19-year-old, was referred for examination at 3 months when hypotonia and lack of head control were noted. Gestation and delivery were uneventful, born at 40 weeks of gestation with weight, 3250 g; length, 50 cm and OFC, 36.5 cm. Psychomotor development was also severely delayed, with no independent walking or speech acquisition. Macrocephaly with normal additional growth parameters, talipes, diminished reflexes in the lower limbs, bilateral talipes equinovarus with a dystonic hallux, dystonic posture hands, kyphosis, hand stereotypies and facial features similar to his sister were also present (Figure 1B). He was also very sociable and communicated with facial expressions.

Brain MRI (Figure 1C) showed diffuse cerebellar atrophy, involving both the vermis and the hemispheres, as well as pontine atrophy, normal spectroscopy and absence of other malformations. Previous normal investigations included metabolic studies such as lysosomal storage parameters, karyotype, array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH). Following medical genetics referral, the family was selected for research based on the observed putative autosomal recessive inheritance pattern.

Molecular Investigation

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was obtained from peripheral blood of index, brother and parents, using salting out methods (Miller et al., 1988).

Exome Sequencing and Copy Number Variants (CNVs) Calling

Exome sequencing (ES) was performed in the index case (II:1). Exome libraries were captured using SureSelect V5-post Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) and 100 bp paired end sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq 2000/2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK v3.4.0) was used to assemble raw data of FASTQ file format onto the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser1 - human assembly: February 2009 (hg19 - NCBI build GRCh37) and variant alleles were annotated using SnpEff (SnpEff_v4.1 g) (Cingolani et al., 2012).

Copy number variants calling based on ES data was performed using CoNIFER2 (Krumm et al., 2012). CNVs with an absolute Z-score greater than 1.7 were considered for analysis. All deletions were considered disruptive, as were duplications in known fully penetrant microdeletion/duplication regions and intragenic CNV duplications. CNVs that overlapped known regions of partial penetrance were considered separately (Firth et al., 2009).

Variant Filtering, in silico Analyses and Segregation Studies

Variants passing following filters were selected for clinical correlation: (a) frequency < 1% (dbSNP, GnomAD Browser, and local databases); (b) gene component, that is, exon and canonical splice acceptor or donor sites; (c) non-synonymous consequence; (d) in silico deleteriousness and spliceogenic effect predictions, using tools: (i) combined Annotation Dependent Depletion scoring3 (CADD threshold ≥ 15) (Kircher et al., 2014); (ii) SpliceSiteFinder-like (SSF, normal score threshold ≥ 70 for SDS and SAS) (Shapiro and Senapathy, 1987); (iii) MaxEntScan (MES, normal score threshold ≥ 0 for SDS and SAS) (Yeo and Burge, 2004); (iv) NNSPLICE (NNS, normal score threshold ≥ 0.4 for SDS and SAS) (Reese et al., 1997); and (v) GeneSplicer (GS, normal score threshold ≥ 0 for SDS and SAS) (Pertea et al., 2001). Variants nomenclature follows the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) recommendations4 (den Dunnen and Antonarakis, 2000).

Segregation studies of the putative pathogenic variants identified by ES were performed by Sanger sequencing analysis using the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied BiosystemsTM, Foster City, CA, United States), after purification of the PCR products with IllustraTM ExoStarTM 1-Step, (GE Healthcare Life Sciences®, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom).

Screening for Low Covered Regions, Genomic Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) and Long-Range PCR

Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software, version 2.2.11 (Robinson et al., 2011) was used to manually analyze exome reads coverage-depth. Low covered exons were then sequenced for detection of SNVs or indels, and a low cycle number PCR was performed to screen for short CNVs. Symmetric and asymmetric amplification studies were preformed essentially as described above.

Comparative CT method (ΔΔCT) was used to detect constitutional copy number variants in SNX14 gene. The TTR exon 2 was used as endogenous control. Q-PCR assay was carried out using the PowerUpTM SYBR® Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and 7500 fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied BiosystemsTM), following manufacturer’s instructions.

To ensure equivalent efficiency of amplification between each pair of primers, the average threshold cycle value (CT) was calculated based on the CT obtained for each of the two replicates from a log10 dilution series of gDNA (20, 10, 5, 2, and 1.25 ng/μl). Data obtained were subjected to linear regression analysis through the semi-logarithmic regression and calculation of the linear correlation value (R2). Only primers that lead to R2 values close to 1 were considered.

In the final computational analysis of the relative copy number variants of each exon, the average CT and associated standard deviations (SD) was calculated for each sample. These values were normalized by the endogenous control, finding the ΔCT and respective SD values. The values of ΔΔCT (and respective SD) were determined by the difference between the ΔCT of all samples and the normal control. The relative quantification (RQ) was finally determined by the formula 2–ΔΔCT (or 2–ΔΔCT ± SD), considering RQ = 1 for the normal control (Weksberg et al., 2005).

To amplify the genomic region encompassing SNX14 introns 7 to 13, by long-range PCR, the RANGER DNA Polymerase (Bioline reagents, London, United Kingdom) was used, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transcript Analysis

RNA was obtained from peripheral blood samples from both patients, using 5 PRIME PerfectPureTM RNA Blood Kit (Fisher Scientific International, Inc., Hampton, NH, United States). A region harboring exons 5 to 15 was amplified using SuperScript® One-Step - RT-PCR with Platinum® Taq kit (InvitrogenTM, Carlsbad, CA, United States) following manufacturer’s instructions. PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel, purified using Corning® Costar® Spin-X® plastic centrifuge tube filters (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and further sequenced as described above.

Results

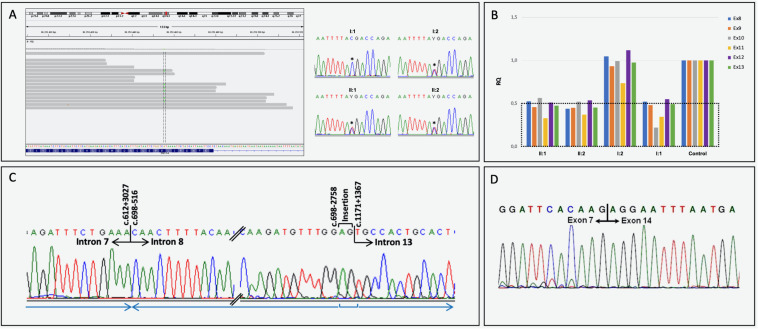

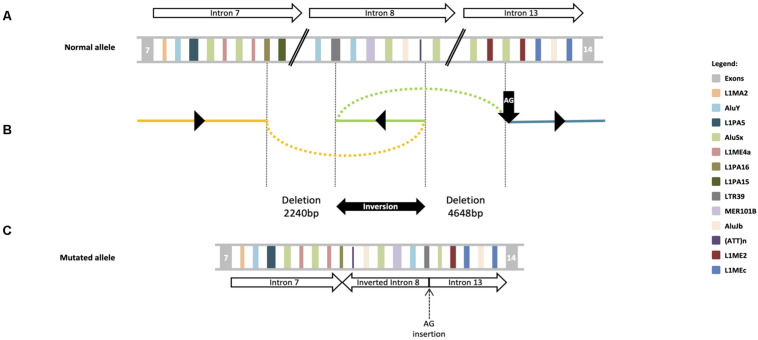

Based on clinical phenotype patients were diagnosed with intellectual disability-coarse facies-macrocephaly-cerebellar hypotrophy syndrome. After ES data filtering, the previously published SNX14 nonsense variant NM_001350532.1: c.1195C>T, p.(Arg399*), described as pathogenic (Akizu et al., 2015; Shukla et al., 2017; Bryant et al., 2018) (ClinVar: RCV000170506.3) was identified. Segregation studies confirmed that this variant was maternally inherited (Figure 2A). These reports as well as the notable clinical phenotype, prompted further SNX14 investigations. However, CNV screening and low-covered regions analyses revealed absence of pathogenic variants. Yet, a low-cycle number (n = 21) amplification of SNX14 exons 8 and 13 suggested a reduced amplification yield in DNA samples from both patients and father when compared to mother’s DNA. A Q-PCR assay was performed, confirming a low copy number amplification of SNX14 exons 8 to 13 shared by the two siblings and father’s samples when compared with control and mother’s samples (Figure 2B). Long-range PCR allowed the characterization of the genomic region breakpoints, revealing a complex rearrangement that includes two deletions, an inversion and an AG insertion, described as NM_001350532.1:c.[612+3028_698-2759del;698-2758_698-516inv;698-515_1171+1366delinsAG] (Figure 2C). Expression analysis enabled the identification of a shorter transcript with a deletion encompassing SNX14 exons 8 to 13: r.613_1171del, p.(Val205Argfs*47) (Figure 2D). Repetitive retroelements neighboring the breakpoints were identified using RepeatMasker (Figure 3; Smith et al., 2015). However, the origin of this complex rearrangement remains to be elucidated, as the well-known mechanisms underlying such phenomena, i.e., non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), homologous recombination (HR), polymerase theta-mediated end joining (TMEJ), microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), fork stalling and template switching (FoSTeS) and microhomology-mediated break induced replication (MMBIR), cannot explain per se this occurrence (Wang et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007; Lieber, 2008; McVey and Lee, 2008; Hastings et al., 2009; Hustedt and Durocher, 2016; Schimmel et al., 2019).

FIGURE 2.

Molecular results. (A) Heterozygous nonsense SNX14 variant NM_001350532.1:c.1195C>T, p.(Arg399*) visualization using IGV, and electropherograms of partial exon 14 sequence generated by Sanger sequencing, with the identified heterozygous variant (*) in the index case (II:1), brother (II:2) and mother (I:2). A normal genotype was identified in the father’s SNX14 exon 14 (I:1). (B) Quantitative analysis (Q-PCR) showing a decrease in exons 8 and 13 copy number in individuals II:1, II:2 and I:1. (C) Partial electropherograms of the genomic region neighboring the rearrangement breakpoints and respective numbering (indicated above corresponding nucleotide): NM_001350532.1:c.[612+3028_698-2759del;698-2758_698-516inv;698-515_1171+1366delinsAG]. The blue arrows indicate the orientation of each genomic fragment. (D) SNX14 transcript analysis performed using lymphocyte-derived RNA of the index case. The wild-type RT-PCR amplicon was amplified in the mother and several controls, while a second smaller amplicon (less 599 bp) was yielded in the patients and father. Sequence trace of the smaller PCR product corresponding to exon 7 - exon 14 junction in the paternally inherited allele, with the absence of exons 8 to 13 (r.613_1171del). This frameshift variant introduces a new stop codon at position 47: p.(Val205Argfs*47);

FIGURE 3.

DEL-INV-DELINS structures at the SNX14 locus. (A) Schematic diagram of exons flanking the rearrangement breakpoints; the statement the partial intron 8 inversion, is followed by the 4648 bp deletion, occurred between introns 8 and 13. Repetitive retroelements are labeled by a unique color. Upper arrows indicate SNX14 introns and respective orientation. (B) Schematic depiction of the genomic genomic complex rearrangement: c.[612+3028_698-2759del;698-2758_698-516inv; 698-515_1171+1366delinsAG]. The 2240 bp deletion occurred between introns 7 (yellow line) and 8 (green line), with breakpoints at L1PA16 and LTR39 elements; the partial intron 8 inversion, is followed by a 4648 bp deletion, that occurred between introns 8 and 13 (blue line), within a AluSx and a AG insertion (vertical black arrow). Black triangles indicate the orientation of each fragment at the mutated allele. (C) A potential structure of the mutant allele is shown in the lower panel in relation to the canonical genomic structure at the top. Lower arrows indicate each SNX14 introns and respective orientation.

Discussion

We report the first non-consanguineous SCAR20 family with two affected patients, carrying compound heterozygous pathogenic variants. ES allowed the identification of a known heterozygous pathogenic variant NM_001350532.1: c.1195C>T, p.(Arg399*), while a second heterozygous pathogenic variant, NM_001350532.1:c.[612+3028_698-2759del;698- 2758_698-516inv;698-515_1171+1366delinsAG], r.613_1171del, p.(Val205Argfs*47), was characterized following a long range PCR.

Complex genomic rearrangements, such as the described herein, are believed to be caused by errors in the DNA double-stand breaks (DSBs) repair system (Carvalho and Lupski, 2016). NHEJ, HR and the recently discovered TMEJ are some of the DSBs repair mechanism already known (Wang et al., 2006; Lieber, 2008; Hustedt and Durocher, 2016; Schimmel et al., 2019). Alu-Alu recombinations are especially common (Sen et al., 2006; Han et al., 2008), which lead us to speculate that an Alu pairing can be the inciting event. This however, cannot explain the full SNX14 rearrangement, as the deletion breakpoints are within divergent types of retroelements, LTRs (one of the oldest primate-specific L1 sequences) and Alu sequences precluding juxtaposition of homologous domains. Since a LINE-1 element appears partially deleted, it is plausible to hypothesize that a SINE-VNTR-Alu (SVA) might be in the origin of this mutated allele, as SVAs are presumably mobilized by trans LINE-1 reverse transcriptase (Hancks and Kazazian, 2010). However, without a stretch of a new retrotransposon or a polyA tail to embody a newly retrotransposed sequence, this also seems unlikely. Interestingly, pathogenic CNVs in other neurodevelopmental genes such as PLP1, MECP2, APP, and SNCA, are believed to be caused by defects in microhomology-mediated DNA repair mechanism (Lee et al., 2007). In fact, Lee et al. (2007) characterized a genomic rearrangement in PLP1 gene, originated by FoSTeS, a mechanism previously known to cause inversions accompanied by duplications and deletions in other organisms such as Escherichia coli (Lee et al., 2007). Although we cannot explain the exact origin of the rearrangement, probably caused by a cascade of errors, it is tempting to speculate that SNX14 gene is prone to the emergence of complex rearrangements as it harbors a large number and variety of repetitive retroelements.

The loss of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) at the SNX14 locus could contribute toward the severity of the SCAR20 phenotype, as ncRNAs are implicated in the regulation of protein coding host gene expression (Boivin et al., 2018). However, according to the NONCODE database5 (assessed at June 22nd 2020) (Liu et al., 2005) there is no ncRNA at these positions in SNX14 gene, so their involvement is unlikely.

Notwithstanding recent developments in sequencing technologies, this kind of genomic rearrangements are overlooked and encumber the identification of the genetic defect particularly in highly heterogeneous diseases such as autosomal recessive intellectual disability (ARID) (Hennekam and Biesecker, 2012). This report highlights the detailed phenotypic evaluation following a multidisciplinary approach as the key for the identification of SNX14 gene involvement.

Conclusion

This study discloses the first non-consanguineous SCAR20 family caused by compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in SNX14 gene. Additionally, this study also emphasizes laboratory-clinician crosstalk as key element to guide successful genetic investigation and, therefore, to increase ARID diagnostic yield. At the end, we broaden the SNX14 phenotypic and mutational spectrum, describing two patients with dystonia and stereotypies beyond the typical clinical features of SCAR20, carrying p.(Arg399*) and a novel rearrangement encompassing introns 7 to 13, undetected by ES.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The study involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the medical ethical committee of the Centro Hospitalar Universit rio do Porto (CHUP, E.P.E.) – REF 2015.196 (168-DEFI/157-CES) – and ICBAS, UP – PROJETO N° 129/2015. Patient’s legal representatives signed informed consent for the use of DNA samples in intellectual disability research and biobanking, and for the publication of patient’s photographs.

Author Contributions

NM: conception and study design, ES data analysis and interpretation, involved in drafting and writing. GS: collected the clinical data, co-writing medical results, interpretation and discussion. CS: shared molecular data analysis and interpretation. IM: data analysis and interpretation, involved in critical reviewing of the manuscript. BR: shared molecular data analysis and interpretation. RS and MP: critical revision, final review, and editing. AB: ES data interpretation, manuscript final critical revision and editing. TT: collected the clinical data, neurological history, co-writing medical results, interpretation and discussion, final review and editing. PJ: conception and study design, involved in drafting and manuscript final revision and editing. All authors gave approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and their family for cooperation. We also would like to acknowledged Professors Kathleen H. Burns, M.D., Ph.D. and Marcel Tijsterman, Ph.D., for their availability, valuable support, and fruitful discussions on the molecular mechanisms underlying the complex genomic rearrangement described herein, as well as José Eduardo Alves, M.D. for their support on brain MRI scan editing and description.

Funding. UMIB was supported by National Funds through the FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portuguese national funding agency for science, research and technology) in the frameworks of the UID/Multi/00215/2019 project – Unit for Multidisciplinary Research in Biomedicine - UMIB/ICBAS/UP. NM and PJ were awarded with CHP grants 2017 DEFI-CHUP, E.P.E. and 2015 (145/12), respectively.

References

- Akizu N., Cantagrel V., Zaki M. S., Al-Gazali L., Wang X., Rosti R. O., et al. (2015). Biallelic mutations in SNX14 cause a syndromic form of cerebellar atrophy and lysosome-autophagosome dysfunction. Nat. Genet. 47 528–534. 10.1038/ng.3256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hashmi N., Mohammed M., Al-Kathir S., Al-Yarubi N., Scott P. (2018). Exome sequencing identifies a novel sorting nexin 14 gene mutation causing cerebellar atrophy and intellectual disability. Case Rep. Genet. 2018:6737938. 10.1155/2018/6737938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin V., Deschamps-Francoeur G., Scott M. S. (2018). Protein coding genes as hosts for noncoding RNA expression. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 75 3–12. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D., Liu Y., Datta S., Hariri H., Seda M., Anderson G., et al. (2018). SNX14 mutations affect endoplasmic reticulum-associated neutral lipid metabolism in autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia 20. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27 1927–1940. 10.1093/hmg/ddy101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho C. M., Lupski J. R. (2016). Mechanisms underlying structural variant formation in genomic disorders. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17 224–238. 10.1038/nrg.2015.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P., Platts A., Wang le L., Coon M., Nguyen T., Wang L., et al. (2012). A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6 80–92. 10.4161/fly.19695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Dunnen J. T., Antonarakis S. E. (2000). Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion. Hum. Mutat. 15 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth H. V., Richards S. M., Bevan A. P., Clayton S., Corpas M., Rajan D., et al. (2009). DECIPHER: database of chromosomal imbalance and phenotype in humans using ensembl resources. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84 524–533. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K., Lee J., Meyer T. J., Remedios P., Goodwin L., Batzer M. A. (2008). L1 recombination-associated deletions generate human genomic variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 19366–19371. 10.1073/pnas.0807866105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancks D. C., Kazazian H. H., Jr. (2010). SVA retrotransposons: evolution and genetic instability. Semin. Cancer Biol. 20 234–245. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings P. J., Ira G., Lupski J. R. (2009). A microhomology-mediated break-induced replication model for the origin of human copy number variation. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000327. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekam R. C., Biesecker L. G. (2012). Next-generation sequencing demands next-generation phenotyping. Hum. Mutat. 33 884–886. 10.1002/humu.22048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustedt N., Durocher D. (2016). The control of DNA repair by the cell cycle. Nat. Cell Biol. 19 1–9. 10.1038/ncb3452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri R., Hu H., Fattahi Z., Musante L., Abedini S. S., Hosseini M., et al. (2015). Exome sequencing and linkage analysis identified novel candidate genes in recessive intellectual disability associated with ataxia. Arch. Iran Med. 18 670–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaca E., Harel T., Pehlivan D., Jhangiani S. N., Gambin T., Coban Akdemir Z., et al. (2015). Genes that affect brain structure and function identified by rare variant analyses of mendelian neurologic disease. Neuron 88 499–513. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher M., Witten D. M., Jain P., O’Roak B. J., Cooper G. M. (2014). A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 46, 310–315. 10.1038/ng.2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm N., Sudmant P. H., Ko A., O’Roak B. J., Malig M., Coe B. P., et al. (2012). Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res. 22 1525–1532. 10.1101/gr.138115.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. A., Carvalho C. M., Lupski J. R. (2007). A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell 131 1235–1247. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber M. R. (2008). The mechanism of human nonhomologous DNA end joining. J. Biol. Chem. 283 1–5. 10.1074/jbc.R700039200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Bai B., Skogerbo G., Cai L., Deng W., Zhang Y., et al. (2005). NONCODE: an integrated knowledge database of non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 D112–D115. 10.1093/nar/gki041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVey M., Lee S. E. (2008). MMEJ repair of double-strand breaks (director’s cut): deleted sequences and alternative endings. Trends Genet. 24 529–538. 10.1016/j.tig.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. A., Dykes D. D., Polesky H. F. (1988). A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:1215. 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertea M., Lin X., Salzberg S. L. (2001). GeneSplicer: a new computational method for splice site prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 1185–1190. 10.1093/nar/29.5.1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese M. G., Eeckman F. H., Kulp D., Haussler D. (1997). Improved splice site detection in Genie. J. Comput. Biol. 4 311–323. 10.1089/cmb.1997.4.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. T., Thorvaldsdottir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E. S., Getz G., et al. (2011). Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29 24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel J., van Schendel R., den Dunnen J. T., Tijsterman M. (2019). Templated insertions: a smoking gun for polymerase theta-mediated end joining. Trends Genet. 35 632–644. 10.1016/j.tig.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S. K., Han K., Wang J., Lee J., Wang H., Callinan P. A., et al. (2006). Human genomic deletions mediated by recombination between Alu elements. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79 41–53. 10.1086/504600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro M. B., Senapathy P. (1987). RNA splice junctions of different classes of eukaryotes: sequence statistics and functional implications in gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 15 7155–7174. 10.1093/nar/15.17.7155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A., Upadhyai P., Shah J., Neethukrishna K., Bielas S., Girisha K. M. (2017). Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia 20: Report of a new patient and review of literature. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 60 118–123. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. F. A., Hubley R., Green P. (2015). Repeat Masker Open-4.0. 2013–2015. 289–300. Avaliable online at: http://www.repeatmasker.org (accessed March 18, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Sousa S. B., Ramos F., Garcia P., Pais R. P., Paiva C., Beales P. L., et al. (2014). Intellectual disability, coarse face, relative macrocephaly, and cerebellar hypotrophy in two sisters. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 164 10–14. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A. C., Williams H., Seto-Salvia N., Bacchelli C., Jenkins D., O’Sullivan M., et al. (2014). Mutations in SNX14 cause a distinctive autosomal-recessive cerebellar ataxia and intellectual disability syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 95 611–621. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillano D., Bertoli-Avella A. M., Kumar Kandaswamy K., Weiss M. E., Koster J., Marais A., et al. (2017). Clinical exome sequencing: results from 2819 samples reflecting 1000 families. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25 176–182. 10.1038/ejhg.2016.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Wu W., Wu W., Rosidi B., Zhang L., Wang H., et al. (2006). PARP-1 and Ku compete for repair of DNA double strand breaks by distinct NHEJ pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 6170–6182. 10.1093/nar/gkl840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weksberg R., Hughes S., Moldovan L., Bassett A. S., Chow E. W., Squire J. A. (2005). A method for accurate detection of genomic microdeletions using real-time quantitative PCR. BMC Genomics 6:180. 10.1186/1471-2164-6-180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G., Burge C. B. (2004). Maximum entropy modeling of short sequence motifs with applications to RNA splicing signals. J. Comput. Biol. 11 377–394. 10.1089/1066527041410418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.