Abstract

Objective:

Patients with biventricular assist devices (BiVADs) have worse outcomes than those with left ventricular assist devices (LVADs). It is unclear whether these outcomes are due to device selection or patient factors. We used propensity score matching to reduce patient heterogeneity and compare outcomes in pediatric patients supported with BiVADs with a similar LVAD cohort.

Methods:

The Pedimacs registry was queried for patients who were supported with BiVAD or LVAD. Patients were analyzed by BiVAD or LVAD at primary implant and the 2 groups were compared before and after using propensity score matching.

Results:

Of 363 patients who met inclusion criteria, 63 (17%) underwent primary BiVAD support. After propensity score matching, differences between cohorts were reduced. Six months after implant, in the BiVAD cohort (LVAD cohort) 52.5% (42.5%) had been transplanted; 32.5% (40%) were alive with device, and 15% (10%) had died. Survival was similar between cohorts (P = .31, log-rank), but patients with BiVADs were more likely to experience a major adverse event in the form of bleeding (P = .04, log-rank). At 1 week and 1 and 3 months’ postimplant, the percentage of patients on mechanical ventilation, on dialysis, or with elevated bilirubin was similar between the 2 groups.

Conclusions:

When propensity scores were used to reduce differences in patient characteristics, there were no differences in survival but more major adverse events in the patients with BiVADs, particularly bleeding. Differences in unmatched patient outcomes between LVAD and BiVAD cohorts likely represent differences in severity of illness rather than mode of support.

Keywords: biventricular assist device, pediatrics

CENTRAL MESSAGE

Differences in unmatched patient outcomes between biventricular assist device versus left ventricular assist device cohorts likely represent differences in severity of illness rather than device strategy.

There have been many changes in the use of pediatric mechanical circulatory support since the original reports on biventricular assist device (BiVAD) support that described extracorporeal, pulsatile support in children with predominantly cardiomyopathy. Trends in device use have shown increasing deployment of continuous-flow and intracorporeal pumps that are used in smaller patients (body surface area<1 m2) as well as to provide left ventricular assist device (LVAD) and BiVAD support.1–3

Use of BiVAD support has been associated with increased mortality compared with LVAD in the initial North American experience with the Berlin Heart EXCOR.4–6 Improved outcomes for patients with LVADs compared with patients with BiVADs also have been demonstrated in the adult population.7 However, there were significant differences in the patient characteristics between the BiVAD and LVAD groups in these publications—both adult and pediatric patients on BiVAD were more critically ill.6,8 These reports have contributed to a decreasing amount of BiVAD use in adult heart failure.

The aim of this study was to analyze outcomes after primary LVAD versus BiVAD implant in the current era and included patients supported with continuous-flow devices or pulsatile devices. Propensity score matching was used to reduce differences in patient characteristics that might influence outcomes.

METHODS

The Interagency Registry of Mechanical Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) is a North American registry sponsored originally by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and now by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. It contains data on>15,000 patients supported on ventricular assist devices (VADs) approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The pediatric component of INTERMACS, Pedimacs (Pediatric Interagency Registry for Mechanical Circulatory Support), collects data on pediatric patients supported with temporary or durable VADs. All pediatric patients receiving LVAD or BiVAD support between September 19, 2012, and March 31, 2017, were included. Patients were excluded if they were supported with a right VAD alone, total artificial heart, or single-ventricle VAD. Patients were classified based on their initial implant strategy, ie, LVAD versus BiVAD at first VAD operation.

Clinical and demographic data are reported with descriptive statistics, and continuous variables are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Comparisons between the LVAD and BiVAD cohorts were performed with Wilcoxon rank sum or χ2 test. Propensity score matching was used to reduce differences between the BiVAD and LVAD cohorts. Variables used in calculating propensity scores were age, total bilirubin at implant, creatinine, cardiac diagnosis (cardiomyopathy vs biventricular congenital heart disease vs transplant vs other), sex, height, implant year, mechanical ventilation, continuous vs pulsatile device in the left ventricle (LV) position, Pedimacs profile (1 vs all others), sodium at implant, and weight. Dichotomizing Pedimacs profile was based on previous reports showing significantly different survival for Pedimacs profile 1 versus Pedimacs profile 2/3.9 LVADs were matched 2:1 to BiVADs using a propensity score algorithm.10 Acceptable matches were defined as VAD recipients who had a difference between propensity scores of less than 0.2 times the standard deviation of propensity scores for the entire cohort.

Survival was estimated by Kaplan–Meier curves with censoring at transplant or device removal for recovery and compared with log-rank test. Multivariable Cox regression was performed with the covariates (age, total bilirubin at implant, cardiac diagnosis [cardiomyopathy vs biventricular congenital heart disease vs transplant vs other], sex, height, implant year, mechanical ventilation, continuous vs pulsatile device in the LV position, Pedimacs profile [1 vs all-others], sodium at implant, and weight) to assess the association between survival and device strategy with censoring at transplant or device removal for recovery. Freedom from major adverse events was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank test. Major adverse events were classified by Pedimacs definitions and included infection, major bleeding, neurologic dysfunction, and device malfunction postdevice implantation. Device malfunction included pump exchanges on pulsatile devices performed for thrombosis. Follow-up data after implant included use of dialysis, use of mechanical ventilation, or elevated bilirubin (>1.2 mg/dL).4 Time points analyzed for follow-up data were 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months’ postimplant.

RESULTS

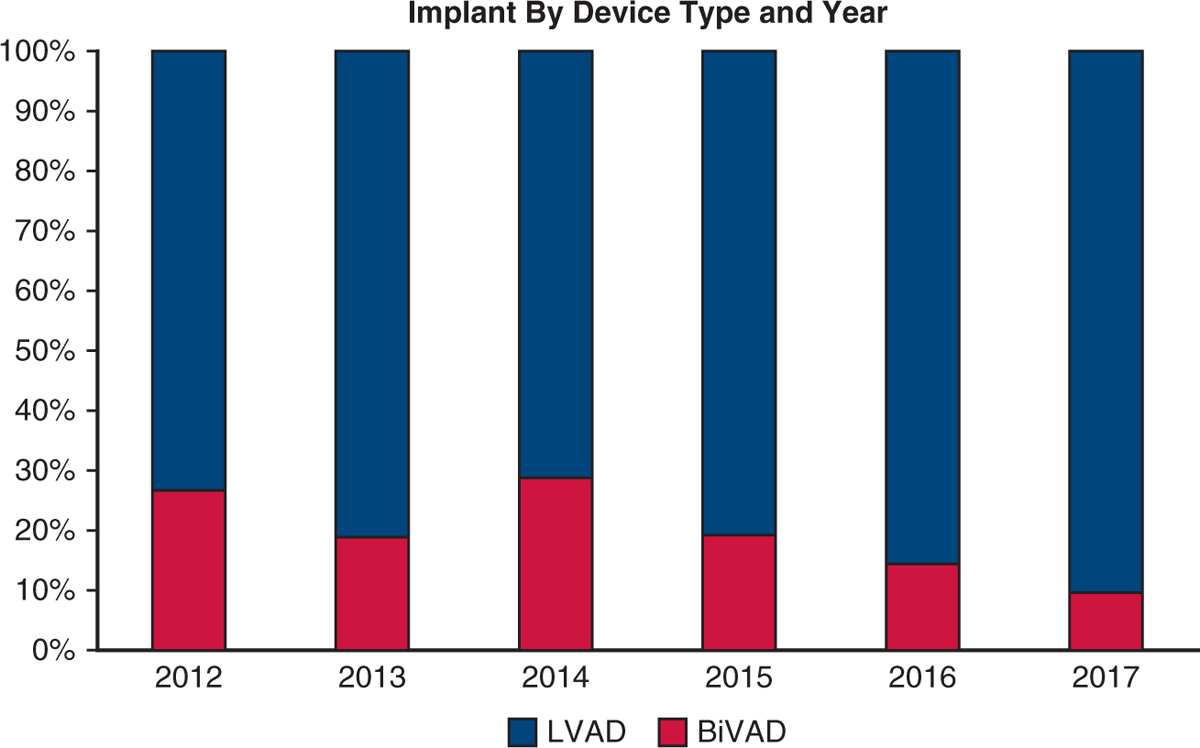

Between September 19, 2012, and March 31, 2017, a total of 456 patients were entered into Pedimacs from 45 different institutions with a mean follow-up of 4.4 months. Of those 456 patients, 376 (82.4%) met study inclusion criteria. Of the 80 patients who were excluded, 63 had single-ventricle heart disease, 8 had total artificial hearts, and 9 had right VAD alone. Of the study patients, 63 (16.8%) had BiVADs and 313 (83.2%) had LVAD alone. Median follow-up for the patients with LVAD was 2.3 months (IQR 0.89–5.2) and 1.6 months (IQR 0.46–4.0) for the patients with BiVAD. The percentage of patients who had a BiVAD peaked in 2012 at 23.5% and has declined since (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Patient cohort. Bar graph depicting the percent of VAD implants that made study inclusion/exclusion criteria that were BiVADs (red) versus LVADs (blue) by year. LVAD, Left ventricular assist device, BiVAD, biventricular assist device.

Unmatched BiVAD Versus LVAD

Table 1 compares patients who had a BiVAD versus LVAD. Patients with BiVADs were more likely to be on mechanical ventilation and have Pedimacs 1 profile, more likely to have congenital heart disease, and less likely to have a continuous-flow device in the LV position. Survival was better for LVAD group (Appendix E1, Figure E1). Factors associated with survival included cardiac diagnosis (hazard ratio [HR], 1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–2.0; P < .001), Pedimacs profile (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3–2.6; P = .013 Pedimacs 1 vs all others), and implant year (HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.0–1.3; P<.01). The 23 unmatched patients with BiVAD were older and predominantly female, had worse renal and liver function, and the majority corresponded to Pedimacs profile 1 at implant (Appendix E1, Table E1). The LVAD group had better freedom from major adverse events compared with the BiVAD group; however, the only difference in major adverse events when analyzed individually was a lower freedom from bleeding events among patients with BiVAD. One week after implant, the LVAD cohort had fewer patients on mechanical ventilation (23.2% vs 64.3%), and on dialysis (4.4% vs 16.7%), but not a significant difference in the percentage of patients with elevated bilirubin level (32.4% vs 47.2%). These differences in patients on mechanical ventilation or dialysis were not evident by 1-month postimplant.

TABLE 1.

Patients with LVAD versus BiVAD at initial implant before and after propensity score matching

| LVAD vs BiVAD before propensity score matching | LVAD vs BiVAD after propensity score matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVAD (n = 313) | BiVAD (n = 63) | Standardized difference | LVAD (n = 80) | BiVAD (n = 40) | Standardized difference | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age, y | 11 (2–16) | 8 (3–14) | 0.74 | 7(1–15) | 6(1–15) | −0.11 |

| Female | 124 (39.6%) | 30 (47.6%) | −0.13 | 21 (47%) | 11 (46%) | 0.016 |

| Weight, kg | 44.2 ± 32.2 | 32.7 ± 30.5 | 0.86 | 20 (7.1–59) | 21 (8.4–46) | 0.29 |

| Height, cm | 144(92–168) | 129 (88–160) | 1.3 | 118 (70–163) | 120 (72–160) | −0.086 |

| Bilirubin at implant, mg/dL | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | 1.4 (0.7–2.7) | −0.33 | 0.81 (0.5–1.5) | 1.2 (0.6–1.6) | −0.16 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 136(133–140) | 138 (134–142) | −0.92 | 137 (134–142) | 138 (133–142) | −0.36 |

| Intubated before implant | 117 (37%) | 38 (60%) | −0.39 | 46 (58%) | 24 (60%) | −0.03 |

| Sinus rhythm | 237 (76%) | 41 (65%) | 0.21 | 57 (71%) | 27 (68%) | 0.05 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 20 (15–29) | 23 (18–41) | −0.48 | 21 (14–31) | 21 (16–35) | −0.19 |

| Pedimacs profile 1 at implant | 83 (27%) | 31 (49%) | −0.39 | 31 (39%) | 16 (40%) | −0.017 |

| Cardiac diagnosis | ||||||

| Congenital heart disease | 25 (8%) | 8 (13%) | −0.14 | 15 (19%) | 8 (23%) | −0.081 |

| DCM | 258 (86%) | 42 (71%) | 0.32 | 60 (75%) | 26 (65%) | 0.18 |

| RCM | 9 (3%) | 4 (7%) | −0.16 | 3 (4%) | 2 (5%) | −0.04 |

| Posttransplant | 8 (3%) | 5 (8%) | −0.19 | 2 (2%) | 3 (7%) | −0.22 |

| Device strategy | ||||||

| Bridge to transplant | 274 (88%) | 55 (87%) | 0.02 | 71 (89%) | 38 (95%) | −0.17 |

| Bridge to recovery | 31 (10%) | 7 (11%) | −0.03 | 7 (9%) | 2 (5%) | 0.12 |

| Destination therapy | 8 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.14 |

| Continuous-flow device in LV | 228 (74%) | 31 (49%) | 0.44 | 37 (46%) | 20 (50%) | −0.065 |

Continuous variables are shown as median, interquartile range; categorical data are displayed as n (%). LVAD, Left ventricular assist device; BiVAD, biventricular assist device, BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Pedimacs, Pediatric Interagency Registry for Mechanical Circulatory Support; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; RCM, restrictive cardiomyopathy; LV, left ventricle.

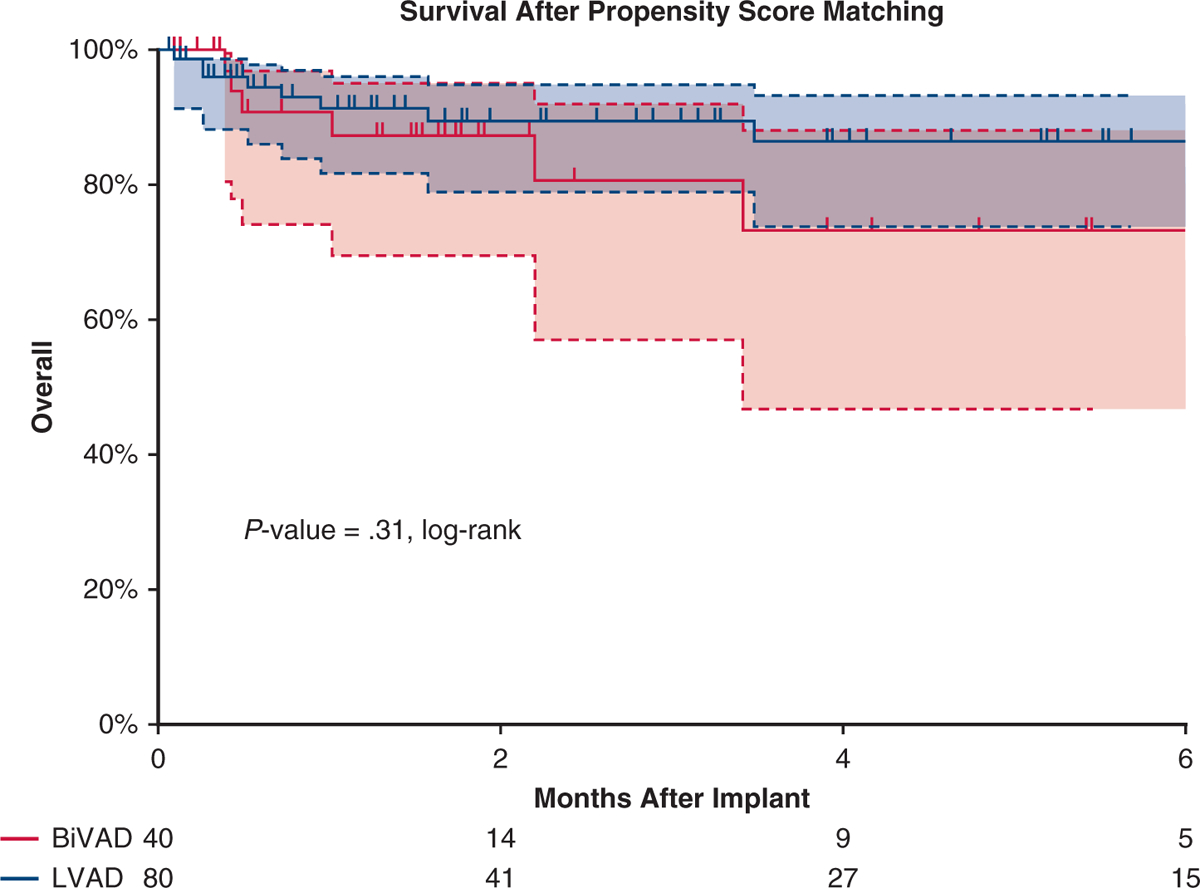

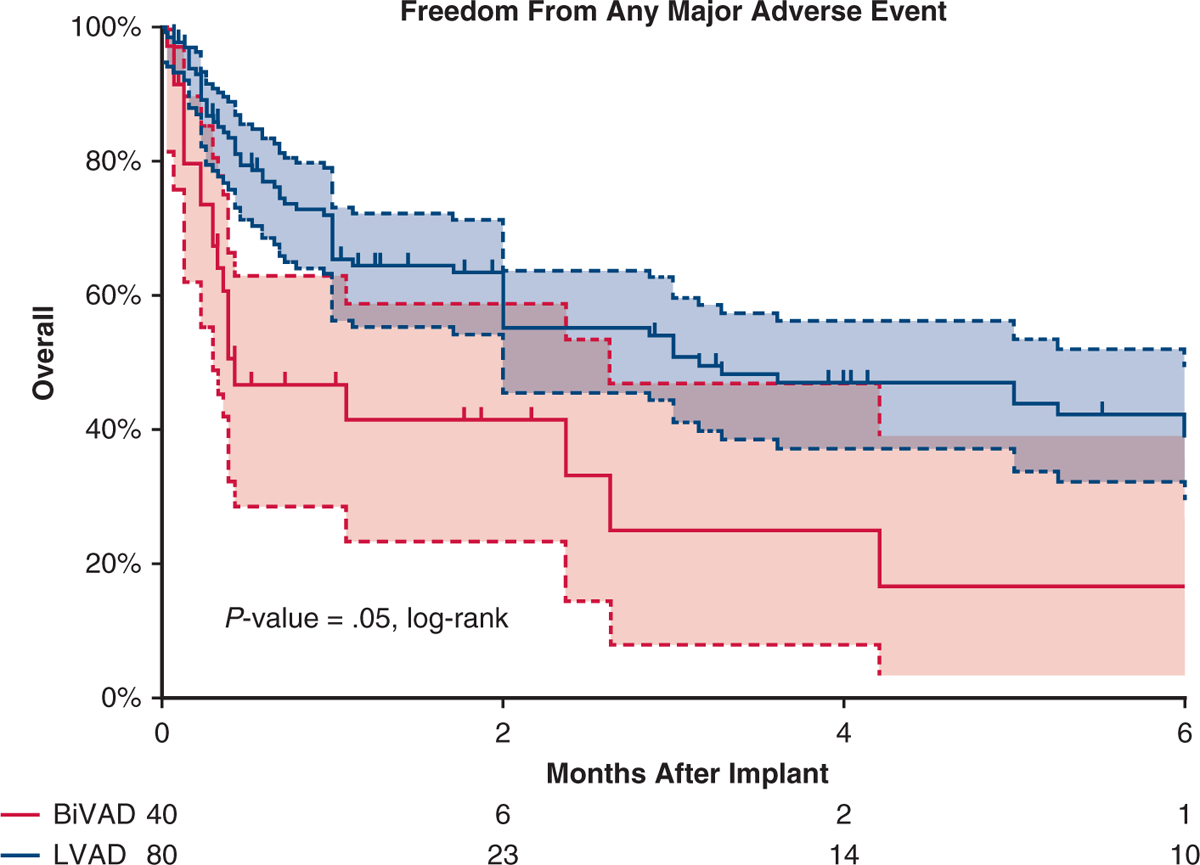

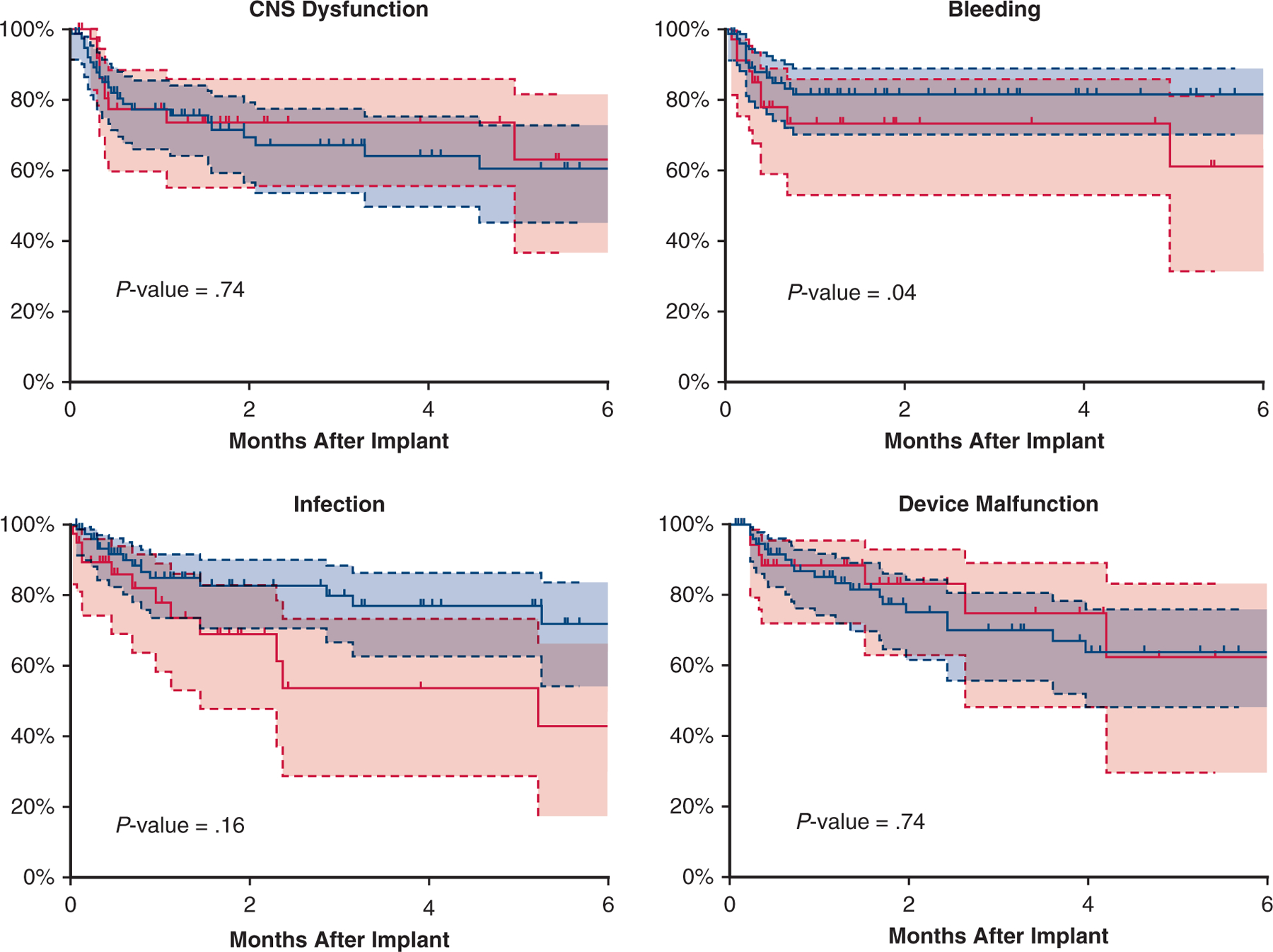

LVAD Versus BiVAD Propensity Matched Analysis

After propensity score matching, differences between the LVAD and BiVAD cohorts were eliminated (Table 1). Overall survival after implant was similar between the matched cohorts (P = .31, log-rank, Figure 2, multivariable Cox regression; HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.5–1.9; P = .9). Six months after implant, in the BiVAD cohort (LVAD cohort), 52.5% (42.5%) had been transplanted, 32.5% (40%) were alive with device, and 15% (10%) had died. The BiVAD group was more likely to experience a major adverse event (P = .05, log-rank, Figure 3). When analyzed individually, the BiVAD cohort was more likely to have bleeding (P = .04, Figure 4), but no difference in device malfunction (P = .74), infection (P = .16), or central nervous system dysfunction (P = .74). At 1-week postimplant, the number of patients with elevated bilirubin was LVAD 21% versus BiVAD 37% (P = .11), patients requiring mechanical ventilation was LVAD 42% versus BiVAD 63%, (P = .06), and patients on dialysis was LVAD 6.6% versus BiVAD 13.3% (P = .22). No differences were seen at 1 and 3 months (Video 1).

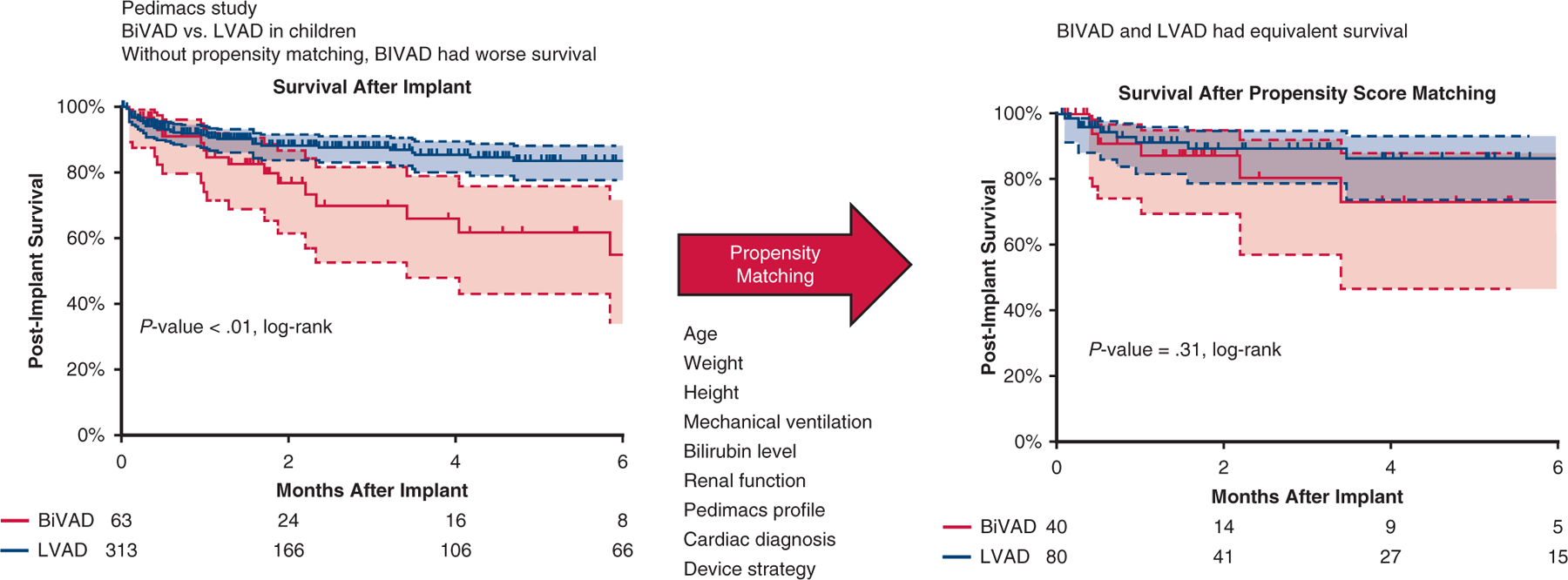

FIGURE 2.

Survival in the matched cohort. Kaplan–Meier curve depicting survival after VAD implant for propensity score–matched patients, with patients on LVAD depicted by a blue curve and those on BiVAD by a red curve. No difference was seen in survival between cohorts. Patients censored at time of transplant and/or at device explant for recovery. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals for each group. BiVAD, Biventricular assist device; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

FIGURE 3.

Adverse events in the matched cohort. Kaplan–Meier curve depicting freedom from any major adverse event after VAD implant for propensity score–matched patients, with patients on LVAD depicted by a blue curve and patients on BiVAD by a red curve. Patients censored at time of transplant and/or at device explant for recovery. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals for each group. BiVAD, Biventricular assist device; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

FIGURE 4.

Freedom from adverse events in the matched cohort. Kaplan–Meier curve depicting freedom from each individual major adverse event after VAD implant for propensity score–matched patients, with patients on LVAD depicted by a blue curve and patients on BiVAD by a red curve. Patients censored at time of transplant and/or at device explant for recovery. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals for each group.

VIDEO 1.

Ventricular assist device in the pediatric population. Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S0022-5223(19)36113-6/fulltext.

DISCUSSION

Over the entirety of the study duration, approximately 17% of pediatric patients required BiVAD support, although there was a downward trend over the final 3 years. This trend likely relates to the recognition that pediatric patients supported by BiVADs have worse survival outcomes and experience more adverse events compared with patients supported with LVADs, a finding recapitulated in this study.4 However, when comparing more homogenous patient populations following propensity matching, apparent differences in support outcomes were minimized and likely due to patient characteristics. BiVADs were more likely to be used in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease presenting with cardiogenic shock and requiring mechanical ventilation as compared with patients supported with LVADs. Propensity score matching eliminated these differences in patient characteristics and revealed similar survival outcomes despite a greater frequency of major bleeding adverse events in BiVAD patients (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Postimplant survival before and after propensity matching. Kaplan–Meier curve depicting post-VAD implant survival before and after propensity score–matched patients, with patients on LVAD depicted by a blue curve and patients on BiVAD by a red curve. No difference was seen in survival between cohorts after propensity matching. Patients censored at time of transplant and/or at device explant for recovery. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals for each group. BiVAD, Biventricular assist device; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

In the Berlin Heart IDE trial, approximately 35% of patients were supported with BiVADs, decreasing to 28% of implants in the Berlin postapproval study.4,11,12 The IDE trial spanned from 2007 to 2010, with the postapproval study running from 2011 to 2015. In our study, only 17% of patients were supported with BiVADs, and the percentage of BiVAD implants has continued to decrease each year since 2014. A similar downtrend in use rates of BiVADs has also been seen in the adult VAD population.7 Early reports of worse outcomes after BiVAD support compared with LVAD alone has led the field to improve patient selection and adopt earlier implantation when feasible.4,5,9 This is evidenced by 57% of the patients in the Berlin Heart IDE trial being in cardiogenic shock (Pedimacs-1) at time of implants versus only 30% of the patients implanted in this analysis.11

The use of BiVADs in pediatrics remains greater than in the adult population, consisting of 17% of pediatric implants in all years of this study as compared with 3% of all adult implants according to INTERMACS reporting.13 The greater percentage of pediatric patients having congenital heart disease versus adults (8% of pediatric VADs vs <1% of adult VADs) combined with increased use of BiVAD support in congenital heart disease indicates that the use of BiVADs in the pediatric VAD population will likely remain greater than in the adult VAD population.9,14 Survival after BiVAD implantation appears to be better for children, with an estimated 75% to 80% survival at 6 months versus 55% to 65% in adults.7 However, this is very likely influenced by the shorter duration of support in children and the greater likelihood of a pediatric patient to be transplanted within 6 months of implant.13

Late conversion to BiVAD support from initial LVAD placement has been associated with worse outcomes compared with initial BiVAD support in the adult VAD population.15 Due to small numbers, we were unable to investigate the outcomes in late conversion to BiVAD support. Risk factors for right ventricular failure after LVAD placement have been studied extensively in the adult VAD population, but little is known in children.16–20 As the pediatric VAD experience grows, identifying risk factors for right ventricular failure post-VAD will help identify which children would benefit from BiVAD support at implant versus LVAD alone, as we have demonstrated that when comparing similar patient profiles LVAD and BiVAD support have similar outcomes. As the number of patients entered into Pedimacs continues to grow, future analyses of the Pedimacs database should investigate outcomes in late conversion to BiVAD in pediatric patients to address these clear gaps in our clinical knowledge.

Adverse events were still more common in patients with BiVADs compared with patients with LVADs after propensity score matching. The difference in adverse events was driven by patients with BiVADs being more likely to suffer from bleeding. There was no difference in the use of dialysis, mechanical ventilation, or presence of elevated bilirubin 1 week, 1 month, or 3 months after implant. Therefore, it appears the extra risk that BiVAD support incurs compared with LVAD alone, when comparing similar patients, is bleeding.

Limitations

The data analyzed are from a multi-institutional registry; therefore, accuracy of data is dependent on correct data entry of reporting institutions. Unrecorded variables may have influenced the decision of using BiVAD versus LVAD support and therefore not been adjusted for in the propensity score analysis. Preoperative heart failure management, anticoagulation strategies plus other postoperative management strategies (use of mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapies) were determined by individual institutions and not recorded in the registry database and may have influenced patient outcomes. The propensity score–matched cohorts have significant differences from other patients in the Pedimacs database in terms of age, cardiac diagnosis, Pedimacs profile, and use of mechanical ventilation. Therefore, the results of the propensity score matched cohorts may not be generalizable to the entire Pedimacs population. The small number of patients in the propensity score matched cohorts prevented analyzing the associations between device type (pulsatile vs continuous-flow) and outcomes. The small number of patients in the propensity score may have resulted in differences not being statistically significant due to reduced statistical power (ie, the percentage of patients intubated at 1-week postimplant). The deidentified dataset did not include brand of VAD and therefore was not included in the study. Given the low number of patients that were able to be propensity score matched a type II error could be present.

CONCLUSIONS

This analysis demonstrates that the differences in BiVAD versus LVAD outcomes are likely significantly impacted by difference in patient characteristics. Patients with BiVAD are more likely to have a bleeding event but had similar survival when matched to similar patients with LVAD. The choice of BiVAD versus LVAD strategy should be dictated by risks for severe and persistent RV failure after VAD placement.

PERSPECTIVE.

The use of ventricular assist devices has increased in the pediatric population. The differences in biventricular assist device (BiVAD) vs left ventricular assist device (LVAD) outcomes are likely driven by patient characteristics. The choice of BiVAD vs LVAD strategy should be dictated by the clinical situation and not by a perceived adverse outcome profile of BiVAD support.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr David Sutcliffe received<$1000 in travel funds for leadership/planning meetings for multicenter quality improvement network (Action Learning Network; not relevant to this study). All other authors have nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

Early financial support for this analysis was provided by The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services under Contract No. HHSN268201100025C. The analysis was completed with funding from The Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BiVAD

Biventricular assist device

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- INTERMACS

Interagency Registry of Mechanical Circulatory Support

- IQR

interquartile range

- LV

Left ventricle

- LVAD

left ventricular assist device

- Pedimacs

Pediatric Interagency Registry for Mechanical Circulatory Support

- VAD

ventricular assist device

APPENDIX E1

Due to the fact that unmatched cohort had significant differences, P values for comparisons were removed. Survival curve for the unmatched groups is included. Here we present the data of the unmatched cohort as well as the data on the 23 patients with a biventricular assist device (BiVAD) who were removed during the propensity score matching.

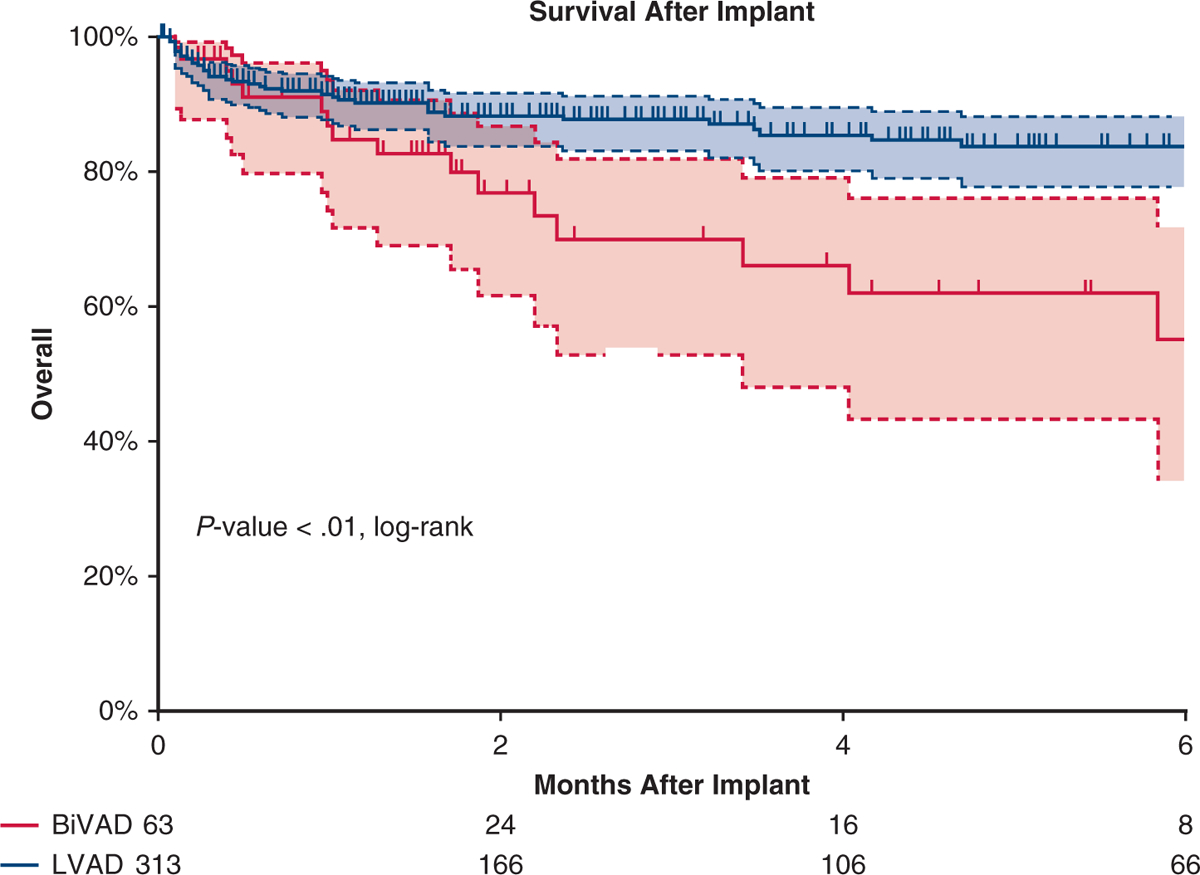

Unmatched Cohort Comparison

As shown in Figure E1, survival was better for the left ventricular assist device (LVAD) group (P = .001). In multi variate Cox regression analysis, device support (BiVAD vs LAVD) was not associated with survival (hazard ratio, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.6–2.4; P = .87). Factors associated with survival included cardiac diagnosis (P<.01, Pedimacs profile P = .013, and implant year (P <.01). The LVAD group had better freedom from major adverse events compared with the BiVAD group (P = .03, log-rank); however, the only difference in major adverse events when analyzed individually was a lower freedom from bleeding events among patients with BiVAD (P < .01, log-rank). One week after implant, the LVAD cohort had fewer patients on mechanical ventilation (23.2% vs 64.3%, P<.01), and on dialysis (4.4% vs 16.7% P<.01) but no significant difference in the percentage of patients with elevated bilirubin (32.4% vs 47.2%, P = .16). These differences in patients on mechanical ventilation or dialysis were not evident by 1-month postimplant (P = .89 and .65, respectively).

Patients on BiVAD Removed After Propensity Score Matching

Table E1 shows the demographic, device strategy, and cardiac diagnosis of the 23 patients with BiVAD eliminated after propensity score matching.

FIGURE E1.

Survival in the unmatched cohort. Kaplan–Meier curve depicting survival after VAD implant in the unmatched cohort. Patients with LVAD are depicted by a blue line and patients with BiVAD by a red line. Patients with LVAD had better survival. Patients censored at time of transplant and/or at device explant for recovery. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals for each group. BIVAD, Biventricular assist device; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

TABLE E1.

Demographic, device strategy, and cardiac diagnosis of the 23 patients on BiVAD eliminated after propensity score matching

| Patient characteristics | BiVAD patients (n = 23) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 11 (5–14) |

| Female | 19 (83%) |

| Weight, kg | 36.3 (17–69) |

| Height, cm | 131 (105–159) |

| Bilirubin at implant, mg/dL | 1.6 (0.8–2.9) |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 140 (137–142) |

| Intubated before implant | 14 (61%) |

| Sinus rhythm | 14 (61%) |

| BUN, mg/dL | 40 (20–47) |

| Pedimacs profile 1 at implant | 15 (65%) |

| Cardiac diagnosis | |

| Congenital heart disease | 1 (4%) |

| DCM | 16 (70%) |

| RCM | 3 (13%) |

| Posttransplant | 3 (13%) |

| Device strategy | |

| Bridge to transplant | 17 (74%) |

| Bridge to recovery | 5 (22%) |

| Destination therapy | 1 (4%) |

| Continuous-flow device in LV | 11 (48%) |

BiVAD, Biventricular assist device; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Pedimacs, Pediatric Interagency Registry for Mechanical Circulatory Support; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; RCM, restrictive cardiomyopathy; LV, left ventricular.

Footnotes

Scanning this QR code will take you to the article title page to access supplementary information.

References

- 1.Peng E, Kirk R, Wrightson N, Duong P, Ferguson L, Griselli M, et al. An extended role of continuous flow device in pediatric mechanical circulatory support. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:620–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miera O, Kirk R, Buchholz H, Schmitt KR, VanderPluym C, Rebeyka IM, et al. A multicenter study of the HeartWare ventricular assist device in small children. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:679–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deshpande SR, Carroll MM, Mao C, Mahle WT, Kanter K. Biventricular support with HeartWare ventricular assist device in a pediatric patient. Pediatr Transplant. 2018;22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almond CS, Morales DL, Blackstone EH, Turrentine MW, Imamura M, Massicotte MP, et al. Berlin Heart EXCOR pediatric ventricular assist device for bridge to heart transplantation in US children. Circulation. 2013;127: 1702–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morales DL, Almond CS, Jaquiss RD, Rosenthal DN, Naftel DC, Massicotte MP, et al. Bridging children of all sizes to cardiac transplantation: the initial multicenter North American experience with the Berlin Heart EXCOR ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zafar F, Jefferies JL, Tjossem CJ, Bryant R, Jaquiss RD, Wearden PD, et al. Biventricular Berlin Heart EXCOR pediatric use across the United States. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:1328–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Blume ED, et al. Sixth INTERMACS annual report: a 10,000-patient database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:555–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleveland JC, Naftel DC, Reece TB, Murray M, Antaki J, Pagani FD, et al. Survival after biventricular assist device implantation: an analysis of the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:862–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blume ED, Rosenthal DN, Rossano JW, Baldwin JT, Eghtesady P, Morales DL, et al. Outcomes of children implanted with ventricular assist devices in the United States: first analysis of the Pediatric Interagency Registry for Mechanical Circulatory Support (PediMACS). J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:578–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosanke J, Bergstralh E. Match 1 or more controls to cases using the GREEDY algorithm. Available at, http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/biostat/sasmacros.cfm. Accessed December 19, 2018.

- 11.Fraser CD, Jaquiss RD, Rosenthal DN, Humpl T, Canter CE, Blackstone EH, et al. Berlin Heart Study I. Prospective trial of a pediatric ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:532–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaquiss RD, Humpl T, Canter CE, Morales DL, Rosenthal DN, Fraser CD. Post-approval Outcomes: the Berlin Heart EXCOR Pediatric in North America. ASAIO J. 2017;63:193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Blume ED, et al. Seventh INTERMACS annual report: 15,000 patients and counting. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:1495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cedars A, Vanderpluym C, Koehl D, Cantor R, Kutty S, Kirklin JK. An Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) analysis of hospitalization, functional status, and mortality after mechanical circulatory support in adults with congenital heart disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37:619–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzpatrick JR, Frederick JR, Hiesinger W, Hsu VM, McCormick RC, Kozin ED, et al. Early planned institution of biventricular mechanical circulatory support results in improved outcomes compared with delayed conversion of a left ventric ular assist device to a biventricular assist device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:971–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowger J, Sundareswaran K, Rogers JG, Park SJ, Pagani FD, Bhat G, et al. Predicting survival in patients receiving continuous flow left ventricular assist devices: the HeartMate II risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kormos RL, Teuteberg JJ, Pagani FD, Russell SD, John R, Miller LW, et al. Right ventricular failure in patients with the HeartMate II continuous-flow left ventricular assist device: incidence, risk factors, and effect on outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:1316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dang NC, Topkara VK, Mercando M, Kay J, Kruger KH, Aboodi MS, et al. Right heart failure after left ventricular assist device implantation in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews JC, Koelling TM, Pagani FD, Aaronson KD. The right ventricular failure risk score a pre-operative tool for assessing the risk of right ventricular failure in left ventricular assist device candidates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2163–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drakos SG, Janicki L, Horne BD, Kfoury AG, Reid BB, Clayson S, et al. Risk factors predictive of right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1030–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]