Abstract

Light scattering has become a common biomedical research tool, enabling diagnostic sensitivity to myriad tissue alterations associated with disease. Light-tissue interactions are particularly attractive for diagnostics due to the variety of contrast mechanisms that can be used, including spectral, angle-resolved, and Fourier-domain detection. Photonic diagnostic tools offer further benefit in that they are non-ionizing, non-invasive, and give real-time feedback. In this review, we summarize recent innovations in light scattering technologies, with a focus on clinical achievements over the previous ten years.

1. Introduction

The study of light-matter interactions has been a primary driver of scientific discovery for hundreds of years. From the earliest days of rationalizing the color of the night sky, to the wave-particle duality that captivated Newton and Huygens, to the detection of gravitational waves, light has proven to be a powerful tool for understanding our world. Although this interaction has primarily been restricted to studying fundamental physics, in the past twenty years, light scattering has become central to both established and emerging biomedical applications [1].

The theory of light scattering has a reputation for complexity, with massive volumes devoted to the study of scattering by objects of relatively simple geometry. Indeed, the classical “inverse problem” of light scattering – that of extracting complete knowledge of an object by measuring its scattered field – is terribly difficult [2, 3]. Inverse scattering problems are ill-conditioned, in that different combinations of object geometries, and of the optical indices of the object and medium, can produce a similar scattered field, and the difficulty is compounded by limitations of the measurement process. Theoretical frameworks of varying complexity help to reduce degrees of freedom associated with the problem of uniqueness, while regularization and statistical methods can be used to diminish measurement errors.

Biomedical applications of light scattering are further complicated by the complexity of biological tissues. Unlike the dielectric sphere studied by Mie [4], tissues exhibit heterogeneity at nearly every length scale. Organization at some scales is countered by disorder at others, with unique distributions of material at the molecular, sub-cellular, cellular, and structural levels. While the intricacy of tissue certainly introduces difficulty for the inverse problem, it also signifies the wealth of information available for quantitative analysis.

Light scattering diagnostic applications are attractive in part because of the wide array of parameters available for measurement. Information encoded in the wavelength [5], wavevector [6], polarization [7], and phase [8] of scattered light may be diagnostically relevant, while optical phenomena such as interference [9] and propagation [10] can reveal previously unmeasurable quantities. The richness of information in the scattered field has led to a wide array of technologies which measure one or more parameters to extract meaningful information from tissue.

In this review, we give an overview of the current state of biomedical applications of light scattering, with a focus on emerging tools over approximately the last ten years. Particular focus is given to applications in tissue, with occasional reference to in vitro studies which lay important groundwork for clinical techniques, or which utilize similar contrast mechanisms to in-vivo technologies to solve a clinical need. While methods are highly varied, and often overlap substantially, we have organized our analysis primarily by contrast mechanism. Sections covering wavelength-dependent scattering, angle-resolved scattering, and Fourier-domain methods are introduced. Optical instrumentation and data analysis are discussed for each technique, with particular focus on clinical results.

2. Wavelength-dependent light scattering

Like most optical processes, elastic scattering in tissue is characterized by a substantive dependence on the wavelength of incident light. A number of techniques have been developed which analyze the spectrum of scattered light from tissue for clinical diagnostic purposes. An overview of these techniques is given below, with a focus on recent developments.

2.1. Elastic-scattering spectroscopy (ESS) and light-scattering spectroscopy (LSS)

Elastic scattering spectroscopy is a non-invasive optical technique which analyzes the spectrum of diffuse scattering in tissue for clinical diagnostic purposes [11]. In typical implementations, light from a broadband source is coupled into a multimode fiber, the distal end of which is placed in direct contact with the tissue to be analyzed. A secondary fiber or fibers placed near the illumination spot collect diffusely scattered photons, which are coupled into a spectrometer for data analysis. ESS has been demonstrated in clinical trials for diagnosis of breast cancer [12], colonic lesions [13], and high grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus [14], among others.

Spectral analysis in ESS may take many forms, and may include direct analysis of specific spectral regions [11], identification of diagnostically relevant portions of the spectrum with machine learning [15], or extraction of tissue optical properties (such as the reduced scattering coefficient, blood volume fraction, or hemoglobin oxygen saturation) by fitting the acquired spectrum to an appropriate model [16]. The best-suited method of analysis is chosen according to the desired application.

In recent years, ESS has expanded to include a wide array of potential applications. Suh et al. has suggested ESS for discriminating benign from malignant disease in ex vivo thyroid samples [17]. Rodriguez-Diaz et al. has conducted a more recent study of colonic polyps, finding >90% sensitivity and specificity for detecting neoplastic polyps [18]. Trials have also been completed showing the ability of ESS to distinguish malignant from benign skin lesions [19], as well as to distinguish between benign, dysplastic and inflammatory prostate samples ex vivo [15].

It should be noted that ESS is sometimes labelled diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, a technique that is similar to ESS but which may encompass both contact and non-contact probes [20]. A vast literature exists on this topic, so we focus here on new developments. In recent years, diffuse reflectance spectroscopy has been applied to in vivo diagnosis of skin cancer [21], and combined with fluorescence measurements for breast surgical margin analysis [22] and identification of peripheral lung tumors [23].

A related technique to elastic scattering spectroscopy is light-scattering spectroscopy. Like ESS, LSS analyzes the spectrum of scattered light to determine morphological properties of tissue. Unlike ESS, LSS seeks to extract light that has been singly scattered which can then be analyzed using Mie theory [5], or more sophisticated models [24]. Analysis of spectral oscillations yields parameters like the size distributions of nuclei, their population density, and refractive index relative to the cytoplasm [25].

In traditional implementations of LSS, light from a broadband source is linearly polarized and directed onto the tissue or cell monolayer surface to be analyzed. Scattered light is passed through an analyzer to the detector plane, in a manner sometimes referred to as polarization-gated LSS [26]. Spectral discrimination occurs by filtering the input light to a narrow, tunable spectral range or by using a spectrally selective means of detection such as a spectrometer or tunable filter. Typically, two measurements of the scattered light are taken, with the analyzer parallel and perpendicular to the illumination polarization axis, respectively. Subtraction of the depolarized component I∥ from the coplanar component I⊥ y yields an intensity ΔI that attempts to isolate singly-scattered photons from the upper epithelium, which have maintained their polarization state. Polarization-subtraction is particularly useful in tissue, as it attempts to remove the contribution of the unpolarized diffusive background. ΔI is acquired for a number of wavelengths, and may also be acquired for various scattering angles [27] or object locations in an imaging configuration [25]. Spectra may also be acquired using an optical fiber probe for in vivo applications [28]. The resulting spectrum is fitted to an analytical model based on Mie theory, with the best fits used to predict nuclear crowding and size distributions. The results correlate highly with those obtained by light microscopy, and are a significant biomarker in histopathological dysplasia detection.

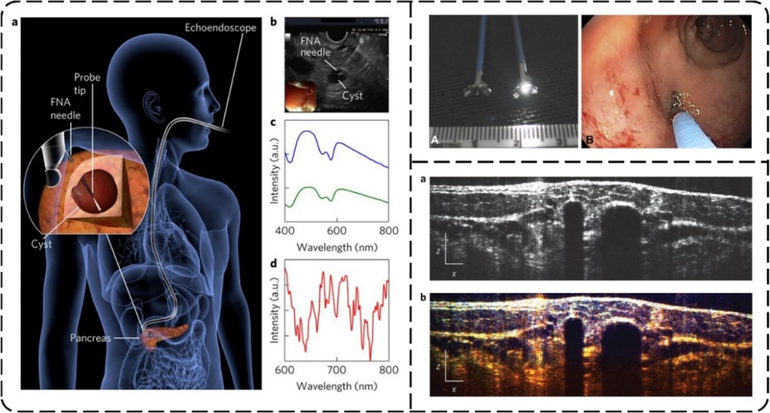

Recent work in LSS has focused on Barrett’s esophagus and other endoscopic applications. Qiu et al. has demonstrated a scanning instrument capable of detecting dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus with 92% sensitivity and 96% specificity [29], and in a more recent study has demonstrated 96% and 97% sensitivity and specificity, respectively [30]. Patel et al. has used polarization gating LSS of the duodenal mucosa to detect early increase in blood supply (EIBS) associated with neoplastic lesions in the pancreas [31]. Further, Zhang et al. has verified the ability of LSS to identify the malignant potential of pancreatic cystic lesions during endoscopy [32]. Representative figures from this study are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(Left) (a) Illustration demonstrating an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration procedure for optical biopsy of the pancreas using LSS. (b) Endoscopic ultrasound image of the needle probe penetrating the cyst. (c) Spectra collected from two distinct source-detector separations, and (d) backscattering component obtained from the LSS spectrum. (Top Right) (a) Comparison of standard biopsy forceps with integrated dual-fiber probe forceps for ESS, and (b) use of forceps for polyp assessment using ESS. (Bottom Right) (a) Conventional OCT image, and (b) molecular imaging true-colour spectroscopic OCT, which uses a dualwindow method for spectral analysis. Reproduced with permission refs. [18, 32, 40]. 2015, Elsevier, and 2017, 2011, Springer Nature.

2.2. Diffuse Reflectance Modeling

The validity of spectral analysis of diffuse reflectance relies heavily on analytical models of varying complexity. One of the most common standards is based on a steady-state diffusion model of light scattering, which describes the radial dependence of diffuse reflectance from tissue [33]. In a seminal paper, Zonios et al. used the diffusion model to extract hemoglobin concentration, hemoglobin oxygen saturation, effective scatterer density, and effective scatterer size from diffuse reflectance measurements of normal and adenomatous colon in vivo [34], with adenomatous tissues showing a marked increase in hemoglobin concentration.

In recent years, diffuse reflectance modeling has been understudied compared with other methods. However, there have been a few advances of note. Improved computational schemes have enabled the use of Monte Carlo methods for arbitrary collection geometries, enabling semi-empirical approximations of diffuse reflectance to replace complex analytic solutions [35]. Two-layers models have been introduced, which more realistically model the vast majority of biological tissues which exhibit an epithelial layer [36]. Additionally, the influence of the phase function has been studied, demonstrating the importance of the probabilistic angular scattering distribution on model results [37]. The long-term trend towards parallelized, high-throughput computing could lead to a resurgence in this type of modeling.

2.3. Spectroscopic OCT

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a well-known biomedical imaging technique which creates tomographic images of tissues, with a resolution on the order of a few microns. While traditional OCT creates depth-resolved reflectivity maps, functional information is not generally available. To solve this problem, spectroscopic OCT (SOCT) allows encoding of spectral information into the tomographic images. SOCT traditionally uses a windowing method [38] such as the short-time Fourier transform (STFT), in which spectral fringes are isolated from wavelength-specific regions to create a series of spectroscopically distinct tomograms. The properties of the window may be chosen according to the desired spectral resolution, which contains a well-known tradeoff with depth resolution in the resulting image.

SOCT has become a popular tool for characterizing tissues, since only an additional processing step is required to obtain spectral information from a Fourier-domain OCT instrument. Here, we present some of the major developments in SOCT in recent years. To overcome the tradeoff in depth vs. spectral resolution, Robles et al. has introduced a dualwindow (DW) method, which uses two spectral window functions of different bandwidths, followed by a point-by-point multiplication to preserve depth resolution [39, 40]. Yi et al. has developed a processing scheme referred to as inverse spectroscopic OCT (ISOCT), which measures wavelength-dependent scattering coefficients using a forward model, and uses these parameters to deduce the refractive index correlation function in tissue [41]. ISOCT is useful for probing the ultrastructural nature of tissues, and has been used to study field carcinogenesis in the pancreas and colon [42].

Clinical applications for SOCT continue to develop for several tissue types. Zhao et al. has shown the ability of SOCT to quantify burn severity in a mouse model [43]. Visible-light spectroscopic OCT has been suggested for a number of applications, including retinal oximetry [44], microvascular hemoglobin mapping [45], examination of amyloid beta plaques in the human and mouse brain [46], bilirubin quantification in tissue phantoms [47] and elastic light scattering spectroscopy in the visible and near infrared [48]. Though applications in oncology have been more limited, Kassinopoulos et al. has demonstrated that a correlation of the spectral derivative from SOCT may be utilized to estimate scatterer size, with good performance distinguishing normal from cancerous human colon ex vivo [49]. Spectroscopic OCT remains a highly active research area.

2.4. Dark-field spectral scatter imaging

Spectroscopic analysis of resected tissue may be performed using more conventional microscopy configurations. One such technique is dark-field spectral scatter imaging, originally developed by Krishnaswamy et al [50]. In this method, a broadband supercontinuum light source is collimated onto a dark-field aperture stop, creating a hollow cylindrical beam which is focused onto the sample. Orthogonal galvanometer-based scanning mirrors are used for raster-scanning, while a custom, broadband f-theta scan lens ensures telecentricity. A CCD-based spectrometer is placed in the detection pathway. The result is a system which efficiently and quickly analyzes the spectral properties of scattered light, while rejecting specular reflected photons.

Dark-field spectral scatter imaging has shown promise in the assessment of breast surgical margins. In particular, this approach achieved 93% sensitivity and 95% specificity in distinguishing benign from malignant pathologies using a threshold-based classifier [51]. Unique spectral signatures from distinct breast pathologies have also been identified, including fibrocytic disease, invasive breast carcinoma, and ductal carcinoma in situ [52].

2.5. Partial wave spectroscopy

Conventional light scattering methods are typically focused on assessing structural changes at the wavelength scale or longer. However, recent work has shown that nanoscale sensitivity is also possible. The approach, termed partial wave spectroscopy (PWS) is based on analyzing spectral fluctuations of backscattered light to determine correlations within the sample [53]. Analysis of these correlations can then be used to assess the health status of individual cells [54].

The PWS approach became a significant optical diagnostic technique when it was linked to the field carcinogenesis effect [55]. In this interpretation, the conditions that may cause carcinogenesis to occur in one site in an organ should be prevalent at other locations in that organ. For example, PWS studies showed that measurements of cytology brushings from histologically normal rectal mucosa can reveal the presence of cancer at distant sites in the colon [56]. The observed changes in PWS signals have also been linked to changes in subcellular features such as chromosome [57] and cytoskeleton [58] organization.

3. Angle-resolved light scattering

Tumorigenic cells exhibit a number of morphologic variations from healthy cells, including changes in the size and shape of the cell, nuclei, and cytoplasmic organelles and alterations in the nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and chromatin structure. Because angular light scattering is highly sensitive to alterations in scatterer properties, angle-resolved scatter detection is a useful tool for the measurement of subcellular morphology. In many cases, angle-resolved light scattering has been used to predict the presence of early carcinogenesis. An overview of these techniques is given below.

3.1. Goniometric measurements

Early studies of angular scattering used a goniometer system to measure the angle-resolved light scattering intensity from suspended cells, isolated nuclei, and mitochondria to demonstrate that light scattering is sensitive to changes in the morphological structure of organelles [59, 60]. In the goniometer system, a collimated beam of light is incident on a tank, which is filled with an index matching solution and the sample located at the center of the rotation axis. A detector is rotated about the sample on the goniometer arm to collect and map the scattered light intensity as a function of angle. By fitting the angular scattering data to simulated scattering distributions of spherical and ellipsoidal scatterers, the size distribution of scatterers can be determined [61].

To better understand light scattering properties of tissue, goniometric measurements have been taken using multicellular spheroids, which better mimic the 3D microenvironment and organization of tumors in vivo. A comparison between intact and dissociated spheroids found general similarity in the angle-resolved light scattering, suggesting that cell-cell interactions, cell shape, and the intercellular matrix do not significantly contribute to angular light scattering in spheroids [62]. However, in the same study, tumorigenic spheroids showed higher relative backscatter intensity when compared to healthy spheroids, consistent with prior results suggesting that rapidly growing cells produce higher backscattering. Spectral, polarimetric, and angular light scattering measurements were also performed on tumor spheroids, where light depolarization was found to be dependent on scattering angle [63]. This effect was attributed to multiple scattering events caused by internal cellular organelles.

Recently, a similar goniometric system was used to acquire angular light scattering measurements from Hela cells in different phases of the cell cycle. It was demonstrated that the intensity of low angle, forward-scattered light and high angle, back-scattered light can be linked to cell size and DNA content within the cell, respectively [64]. Further study of these optical signatures can provide relevant information on the physiologic structure of tumor cells.

3.2. Finite-difference time-domain methods

While analytic solutions of angular scattering exist for geometrically simple objects, cells and tissues exhibit substantial optical heterogeneity [67, 68], making exact solutions of the angular scattering problem difficult. Finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) computational methods have been used to predict scattering distributions for cells and organelles of arbitrary shape and refractive index [60]. The FDTD algorithm spatially and temporally discretizes the Maxwell equations, which are solved over multiple time steps using finite difference equations within a 3D lattice of grid points. Using FDTD, angular scattering was determined to be sensitive to changes between healthy and precancerous cells, particularly in regards to nuclear atypia [69, 70]. Recent implementations of the FDTD algorithm have been greatly accelerated through GPU based execution, enabling more complex light scattering analysis [71–73]. Using these algorithms, various groups have explored the effects of nuclear size and refractive index [74, 75], collagen fiber networks [76], and epithelial depth [77] on light scattering through neoplastic progression in cells.

3.3. Four-dimensional elastic light-scattering fingerprinting

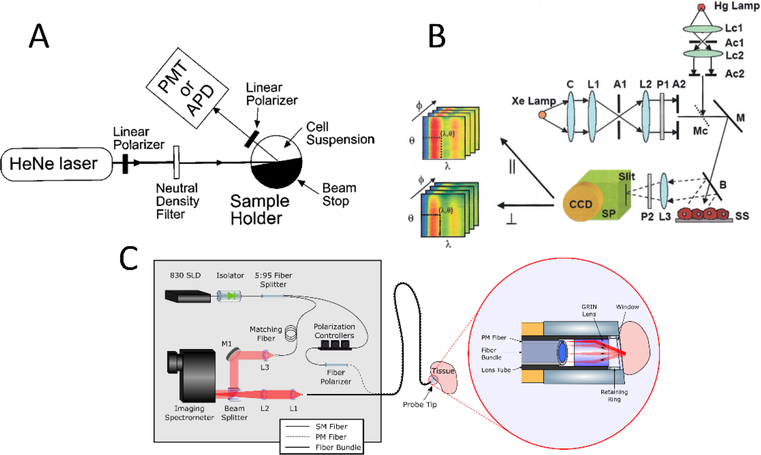

As this review notes, both spectral and angular scattering information are useful in extracting morphological information from cells. A technique for measuring both properties, termed four-dimensional elastic light-scattering fingerprinting (4D-ELF) was developed by Roy et al. An extension of light-scattering spectroscopy, 4D-ELF measures spectral, angular, azimuthal, and polarization dependence of light scattering from a sample, and uses the angular scattering data to calculate higher fractal dimension in tissue architecture during carcinogenesis [65, 78]. A simplified endoscopic version of this technology has also been utilized to investigate mucosal microvascular blood supply associated with colonic neoplasia [79]. A schematic diagram for a typical 4D-ELF system is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Instruments for studying angular scattering from cellular and tissue samples: (A) Goniometric system, (B) four-dimensional elastic light-scattering fingerprints, and (C) angle-resolved low coherence interferometry. Reproduced with permission from refs. [61, 65, 66] 2002, 2011 SPIE and 2004, Elsevier.

3.4. Angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry

In addition to providing scattering information, spectral detection of light may be used in an interferometry scheme to provide coherence-gated localization of scatterer depth in tissue. Angle-resolved low coherence interferometry (a/LCI) is a technique which implements angle-resolved backscattering detection via Fourier-domain spatial detection of angular scattering, with depth resolution utilizing low-coherence interferometry. Early a/LCI studies used the coherence-gated scattering distribution to determine the fractal organization of a cell monolayer [80]. More commonly, the angular scattering profile from a/LCI can be compared with lookup tables of angular scattering profiles derived from Mie theory, to quantify the nuclear morphology from the basal layer of the epithelium during neoplastic transformation [81, 82].

a/LCI has enjoyed a wealth of success in diagnosing dysplasia in the clinic, with standalone systems developed for detecting esophageal [83, 84], intestinal [85], and cervical dysplasia [66, 86]. In the clinical studies, repeated optical biopsies were taken with the a/LCI instrument and compared to histopathological analysis of co-registered tissue biopsies. Here, a/LCI demonstrated high sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value (NPV) in detecting dysplasia (92.9% sensitivity, 83.6% specificity, 98.2% NPV in the esophagus; 100% sensitivity, 97% specificity, and 100% NPV in the cervix). In addition, recent developments have incorporated scanning capability [87] and co-registered OCT imaging [88] to improve the clinical application of a/LCI. a/LCI was further developed to detect angular scattering across a two-dimensional solid-angle for determining the aspect ratio and orientation of spheroidal scatterers, and for measuring spatial correlation distances of scatterers within tissue [88–90]. A schematic diagram of a typical a/LCI instrument is shown in Figure 2(c).

4. Fourier-domain methods

Fourier-domain techniques present an alternative to the direct measurement of scattering angles. As a general rule, the angle and position of a collection of scatterers in a sample plane are fully characterized by a transfer function. Interrogating the spatial frequency response of a sample is therefore equivalent to measuring its angular profile under certain assumption and conditions. Several such techniques have been utilized to perform scattering measurements in cells and tissue.

4.1. Fourier transform light scattering

Fourier transform light scattering (FTLS) was first reported by Ding et al in 2008 [8]. FTLS uses diffraction phase microscopy (DPM) [93] to acquire a wavefront image near the image plane of the microscope. The acquired wavefront image is complex, including both phase and amplitude information from the sample. The scatterers in the sample plane impart a perturbation to the wavefront. A simple Fourier transform of this field is equivalent to optically propagating the scattered light and analyzing the scattered field as a function of angle.

The main advantages of FTLS are the ability to obtain scattering information from a small number of cells, and relatedly, the ability to produce scattering maps with high spatial resolution. These features allow FTLS to be used with sparse cells, such as red blood cells [8]. Further, the imaging-based approach of FTLS allows the scattering signal from nonisotropic cells to be individually rotated into alignment and summed, which would not be possible with bulk scattering measurements.

Jo et al. used FTLS to characterize the scattering of rod-shaped bacteria, finding significant differences between the 2D scattering profiles of four superficially similar bacterial species [94]. These studies were expanded to identify unknown bacteria by feeding their FTLS-derived scattering profiles into a principal component analysis classifier, obtaining an overall classification accuracy of over 94% [95]. This FTLS-based bacterial assay could potentially be used to rapidly identify bacteria without the need for stains or labels.

Other in vitro models have benefited from the high-resolution dynamic scattering analysis provided by FTLS. The transport dynamics of an in vitro neural cell culture were characterized by Mir et al [96]. In this work, the spatial correlation of subcellular structures was measured by obtaining the power spectrum of the Fourier-domain image, which is related to the autocorrelation of the complex field by the Wiener-Khinchin theorem. Mir et al utilized these techniques to measure neurons during growth, finding that distinct periods of growth exist with quantitative differences in behavior [96]. The idea of examining properties of the Fourier-domain image is similar to optical scatter imaging (OSI), in which a digital micromirror device in the Fourier place enables characterization of particle shape, orientation, and aspect ratio [97]. OSI has also been applied to study the fragmentation of mitochondria during apoptosis [98].

FTLS has also been demonstrated in tissue samples. Shortly after introducing the FTLS method, Ding et al explored the scattering profiles of 5 μm thick slices of rat kidney, liver, and brain tissue and found significant differences in scattering and transport mean-free paths derived from the cross-sections measured by FTLS [99]. More recently, Lee et al used FTLS to map the scattering coefficient and anisotropy in the grey and white matter of both healthy and Alzheimer’s diseased mouse brains [100]. FTLS in tissue is generally limited, however, to analysis of thin slices. Without being able to scan living tissue, the high temporal resolution of FTLS is not fully utilized.

4.2. Spatial frequency-domain imaging

Another light scattering method takes a somewhat reversed approach to FTLS. Spatial frequency-domain imaging (SFDI), first introduced by Cuccia et al in 2005 [101], encodes frequency-domain interrogation into the illumination. A series of sinusoidal stripes of varying frequency are projected onto a sample using a spatial light modulator (SLM) or digital micromirror device (DMD). The light scattered within and reflected from the sample is imaged to a camera. However, each frequency of illumination does not penetrate equally into the sample. Higher frequencies are attenuated more readily to scattering, while lower frequencies achieve greater penetration. Analyzing the input frequency response therefore reveals scattering properties as a function of depth, allowing SFDI to yield tomographic volumes of scattering data [101]. SFDI can also be performed with multiple wavelengths of light to capture color-dependent scattering and absorption properties, enabling measurement of spectrally evident properties, such as blood oxygenation [102].

Compared to many other techniques for assessing light scattering, SFDI is more amenable towards implementation in clinical settings. By performing imaging in the reflective direction, and requiring only basic structural modulations of the illumination, a SFDI system can acquire its data as an external device pointed towards the sample tissue, lending itself readily to clinical translation. The authors of the original SFDI manuscript extended their original phantom study towards in vivo imaging of human skin and subcutaneous tissue in 2009 [92].

Unsurprisingly, SFDI finds many applications in dermatology, as many skin disorders benefit from a quantitative picture of subcutaneous tissue. SFDI has been used to evaluate burn severity [103], to identify patients at risk of developing pressure ulcers [104], and to characterize the cancer risk of actinic skin lesions [105].

SFDI is also being used to discriminate tumors and tumor margins based on the distinct scattering properties of cancerous tissue. Rohrbach et al used SFDI to map skin cancer tumors by absorption, scattering, blood oxygen saturation, and hemoglobin [106]. McClatchy et al found that SFDI could classify stroma, epithelium, and adipose tissue in ex vivo human breast tissue that were well-validated against histology [107].

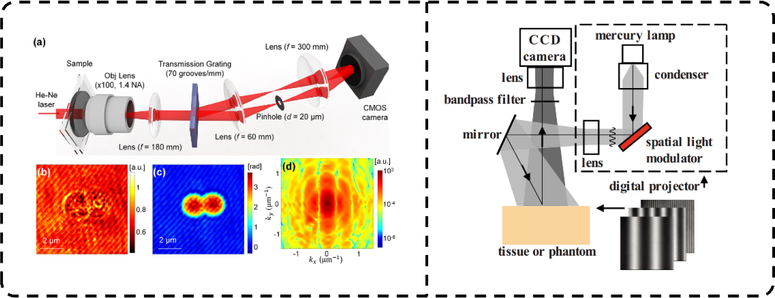

The brain presents an even greater challenge for subsurface imaging, though various groups have explored using SFDI for neurobiology. An SFDI study of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s was able to detect significant differences in the wavelength-dependent scattering and absorption of the brain between control and disease states, even when imaging in vivo through the intact skull [108]. By extracting absorption cross-sections, SFDI has also been used to image drug delivery in rat brains [109]. Changes in tissue absorption and scattering due to hypoxic injury have also enabled SFDI study of the damage to rat brains resulting from cardiac arrest [110]. A block diagram showing SFDI instrumentation is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

(Left) (a) Setup for diffraction phase microscopy, which enables Fourier transform light scattering. (b) Amplitude image, and (c) phase maps of polymethyl methacrylate spheres, with (d) the associated light scattering pattern computed from the phase image. (Right) Instrumentation schematic for spatial frequency-domain imaging. Reproduced with permission from refs. [91, 92] 2012, The Optical Society, and 2009, SPIE.

It should be noted that many implementations of SFDI rely on adaptations of the diffusion theory of photon propagation, in contrast to many of the techniques discussed in this review which operate using primarily single-scattered photons. Bridging this gap, Kanick et al has used high spatial frequency illumination to isolate light in the sub-diffuse transport regime [111], with observed differences between normal and scar tissue in a healthy volunteer. Further examination of the assumptions inherent to photon propagation models in SFDI would be of great interest to the broader optics community.

5. Discussion

A comprehensive index of the techniques discussed in this review is shown in Table 1. For a substantial portion of these techniques, a familiar pattern emerges. First, a mathematical model of varying complexity is developed to model tissue scattering. Next, a physical property associated with a variable in the model is measured, and the data are fitted to a library of model variations until a best fit is found. This general framework is present in some form in ESS, LSS, diffuse reflectance modeling, ISOCT, and a/LCI, among others, and allows for measurement of quantities that are difficult to access, as when partial-wave spectroscopy demonstrates sensitivity to correlations at the nanoscale [112] despite these features existing an order of magnitude or more below the diffraction limit. As always, limitations should be acknowledged. In particular, this procedure constrains the range and resolution of possible measurements to a pre-computed class of model outcomes defined by an array of input variables. These models make assumptions regarding tissue morphology, composition, scatterer size and shape, and optical properties which are accurate generally, but may not countenance statistical variations in patients or tissues. In some cases, these assumptions may be simply incorrect, as assumptions of the nuclear refractive index increasingly appear to have been [67, 68, 113]. Deviations from the assumed simplicity of analytic models may produce errors in analysis, and ultimately limit device performance over large populations. Such limitations are not often identified in preliminary studies, but in truth may contribute heavily to the ultimate clinical effectiveness of these techniques.

Table 1.

Summary of Biomedical Light Scattering Techniques

| Representative Applications in Tissue | ||

|---|---|---|

| Elastic-scattering spectroscopy (ESS) | Spectral | Bladder Cancer [11]; Breast cancer [12]; Colonic lesions [13]; Dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus [14]; Malignancy in ex vivo thyroid [17]; Colonic polyps [18]; Skin lesions [19]; Dysplastic and inflammatory prostate ex vivo [11, 15], |

| Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy | Spectral | Skin cancer [21]; Breast surgical margin analysis [22]; Peripheral lung tumors [23]. |

| Light-scattering spectroscopy (LSS) | Spectral, Polarization | Dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus [5, 28–30]; Field carcinogenesis (rat model) [24]; Colonic adenoma [25]; EIBS during colon carcinogenesis [26]; EIBS associated with neoplastic pancreatic lesions [31]; Malignant potential of pancreatic cystic lesions [32]. |

| Diffuse reflectance modeling | Spectral | Normal and adenomatous colon in vivo [34] |

| Spectroscopic OCT (SOCT) | Spectral, Depth-resolved (Interferometric) | Carcinogenesis in the pancreas and colon [42]; Burn severity [43]; Retinal oximetry [44]; Microvascular hemoglobin mapping [45]; Amyloid beta plaques in the human and mouse brain [46]; Bilirubin quantification [47]; Light scattering spectroscopy of the retina [48]; Colon cancer ex vivo [49], |

| Dark-field spectral scatter imaging | Spectral | Breast surgical margins [51]; Various breast pathologies [52]. |

| Partial wave spectroscopy (PWS) | Spectral | Field carcinogenesis in the colon, pancreas, and lung [55]; Cytological brushings of the rectal mucosa [56]; |

| Goniometric measurements | Angle-resolved | Morphological structure of organelles [59–61]; Multicellular spheroids [62, 63]; DNA content [64]. |

| Finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) methods | Angle-resolved | Nuclear size and refractive index [74, 75]; Collagen fiber networks [76]; Epithelial depth [77]; |

| Four-dimensional elastic light-scattering fingerprinting (4D-ELF) | Spectral, Angle-resolved, Azimuthal, Polarization | Colon carcinogenesis (rat model) [65, 78]; Early carcinogenesis of the rectal mucosa [79], |

| Angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry (a/LCI) | Angle-resolved, Depth-resolved (Interferometric) | Esophageal dysplasia [83, 84]; Intestinal dysplasia [85]; Cervical dysplasia [66, 86]; Grading of esophageal neoplasia (rat model) [82]; Esophageal adenocarcinoma (rat model) and retinal degradation (mouse model) [88]; |

| Fourier transform light scattering (FTLS) | Fourier-domain, Angle-resolved | Identification of bacterial species [94, 95]; Neural transport and growth dynamics [96]; Alzheimer’s disease (mouse model) [100], |

| Spatial frequency-domain imaging (SFDI) | Fourier-domain, Spectral | Blood oxygenation [102]; Burn severity [103]; Pressure ulcer risk assessment [104]; Cancer risk of actinic skin lesions [105]; Skin cancer [106]; Breast tissue classification [107]; Alzheimer’s disease (mouse model) [108]; Brain damage from cardiac arrest (mouse model) [110]; |

One potential solution to the issues inherent in model-fitting is machine learning. Analytic models may be insufficiently complex (or overly complex), imbalanced in certain variables, or improperly characterize the real-world range of parameters. Instead, any series of measurements can simply be entered into a machine learning algorithm, which will find the optimum discriminatory variables in high-dimensional space. While obviously an effective strategy, machine learning approaches should take care that they are not over-fitting to a particular dataset at the expense of a more generalizable diagnostic. Prospective validation studies (in which classifications are based on parameter cutoffs from previous studies) are underrepresented in the literature, and execution of such studies should help prevent machine learning classifiers which are accurate for the case of a small feasibility study but not valid for larger populations.

Many analytic models of light scattering take extreme caution in developing complex theory to explain the scattering process. Less care is generally taken when assuming physical constants, with many works content to pull parameters related to refractive index, size distribution, and nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio from decades-old studies [114, 115]. There is a general dearth of basic research related to the statistical presentation of scattering properties, including variation on the temporal and spatial scales, and across cell lines and types. Emerging technologies like refractive-index tomography [116, 117], as well as more established techniques like digital holographic microscopy [118, 119], are well-suited to this type of characterization. This type of work is labor intensive and often underappreciated, but an improved body of knowledge regarding the optical properties of biological specimens would provide a more solid foundation for models of tissue scattering.

Computational resources have improved markedly in recent years, however, it is not obvious that an accompanying renaissance in numerical light scattering studies, such as FDTD modeling, has occurred. This is particularly interesting given the additional advances in parallel computing and GPU-based processing in this time period. While the exact reason is unclear, we can speculate that further simulations of light scattering from homogenous tissue models may be uninteresting, and also have been shown to exhibit results heavily dependent on initial assumptions of the phase function and other parameters [37]. A potential avenue of new research exists in creating more realistic models of cells and tissues using quantitative measurements. Comparisons of light scattering between realistic models of cellular architecture and simplified models would provide a stronger empirical backing for the use of simplified models, and further legitimize diagnostic modalities which rely on light scattering.

Substantial innovation in the field of scattering-based optical diagnostics continues to occur at the level of basic research, and considerable support for established technologies like OCT is available within commercialized entities. However, there is a dearth of movement between the two spaces, with a number of optical technologies unable to realize commercial success despite substantial success in clinical studies. A portion of this stasis is likely related to mandatory regulatory pathways defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in which devices lacking a cleared predicate are required to undergo Premarket Approval (PMA). The PMA process can require a substantial investment, with years of time and significant expenditure before completion. Recent adoption of the de novo process by the FDA promises to enable a more accessible pathway for Class I devices, similar to the less burdensome 510(k) process. Further innovations in regulatory pathways, such as specialized pathways for low risk photonic diagnostics may incentivize the formation of new companies and ventures around these techniques.

A common theme in many of the studies discussed in this review is the comparison of a specific measurement technique with the “gold standard” of histopathology, the premise being that scattering-based diagnostics should match the classification of a representative biopsy examined by an expert pathologist. Histopathology is a tried and true method, and it has remained the standard of care in essentially all branches of medicine for over a century. However, it is also not without limitations, with issues including sampling error and relatively high inter-observer variability (<50% agreement) for some conditions like esophageal dysplasia [120]. On the occasion when an optical technique is sensitive to pathology which is not discovered by a biopsy, a comparative study would classify this as a failure of the optical technology rather than a failure of the pathologist. Extending such validation studies to include supplemental techniques such as immunohistochemistry [121] and genomic screening will help improve validation of new photonic diagnostic devices.

This review has focused primarily on elastic scattering, however, a significant literature on inelastic scattering exists as well. Diagnostic modalities based on Raman scattering have been quite popular over the years [122–124], and Brillouin spectroscopy has seen a recent increase in interest driven primarily by improved spectrometer technology [125–127]. Regulatory pathway reform may help to incentivize commercialization of these technologies as well.

6. Conclusion

In this review, we have given an examination of the current state of photonic technologies which utilize light scattering for disease detection. Techniques which measure spectral, angular, and phase properties of the scattered field have been presented, along with examinations of the associated instrumentation and data processing schemes. A discussion of the state of the field was presented. Rich innovation on the level of basic research, combined with prudent regulatory reform and continued investment in translational studies will allow for continued success in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

Z.S. gratefully acknowledges support from the NSF-GRFP program.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 CA167421, R01 CA210544)

Footnotes

Disclosures

AW: Lumedica, Inc. (I, P)

References

- [1].Wax A and Backman V, Biomedical applications of light scattering. McGraw Hill Professional, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [2].van de Hulst HC, Light scattering by small particles. Courier Corporation, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ishimaru A, Wave propagation and scattering in random media. John Wiley & Sons, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mie G, “Beiträge zur Optik trüber Medien, speziell kolloidaler Metallösungen,” Annalen der physik, vol. 330, no. 3, pp. 377–445, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Perelman L et al. , “Observation of periodic fine structure in reflectance from biological tissue: a new technique for measuring nuclear size distribution,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 80, no. 3, p. 627, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wax A et al. , “In situ detection of neoplastic transformation and chemopreventive effects in rat esophagus epithelium using angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry,” Cancer research, vol. 63, no. 13, pp. 3556–3559, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].De Boer JF, Milner TE, van Gemert MJ, and Nelson JS, “Two-dimensional birefringence imaging in biological tissue by polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography,” Optics letters, vol. 22, no. 12, pp. 934–936, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ding H, Wang Z, Nguyen F, Boppart SA, and Popescu G, “Fourier transform light scattering of inhomogeneous and dynamic structures,” Phys Rev Lett, vol. 101, no. 23, p. 238102, December 5 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Huang D et al. , “Optical coherence tomography,” Science (New York, NY), vol. 254, no. 5035, p. 1178, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rinehart MT, Park HS, and Wax A, “Influence of defocus on quantitative analysis of microscopic objects and individual cells with digital holography,” Biomedical optics express, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 2067–2075, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mourant JR, Bigio IJ, Boyer J, Conn RL, Johnson T, and Shimada T, “Spectroscopic diagnosis of bladder cancer with elastic light scattering,” Lasers in surgery and medicine, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 350–357, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bigio IJ et al. , “Diagnosis of breast cancer using elastic-scattering spectroscopy: preliminary clinical results,” Journal of biomedical optics, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 221–229, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dhar A et al. , “Elastic scattering spectroscopy for the diagnosis of colonic lesions: initial results of a novel optical biopsy technique,” Gastrointestinal endoscopy, vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 257–261, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lovat LB et al. , “Elastic scattering spectroscopy accurately detects high grade dysplasia and cancer in Barrett’s oesophagus,” Gut vol. 55, no. 8, pp. 1078–1083, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].A’amar O, Liou L, Rodriguez-Diaz E, De las Morenas A, and Bigio I, “Comparison of elastic scattering spectroscopy with histology in ex vivo prostate glands: potential application for optically guided biopsy and directed treatment,” Lasers in medical science, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 1323–1329, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Reif R, Amorosino MS, Calabro KW, Aamar OM, Singh SK, and Bigio IJ, “Analysis of changes in reflectance measurements on biological tissues subjected to different probe pressures,” 2008, vol. 13, p. 3: SPIE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Suh H, A’amar O, Rodriguez-Diaz E, Lee S, Bigio I, and Rosen JE, “Elastic light-scattering spectroscopy for discrimination of benign from malignant disease in thyroid nodules,” Annals of surgical oncology, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 1300–1305, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rodriguez-Diaz E, Huang Q, Cerda SR, O’Brien MJ, Bigio IJ, and Singh SK, “Endoscopic histological assessment of colonic polyps by using elastic scattering spectroscopy,” Gastrointestinal endoscopy, vol. 81, no. 3, pp. 539–547, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Upile T, Jerjes W, Radhi H, Mahil J, Rao A, and Hopper C, “Elastic scattering spectroscopy in assessing skin lesions: an “in vivo” study,” Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 132–141, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bigio IJ and Mourant JR, “Ultraviolet and visible spectroscopies for tissue diagnostics: fluorescence spectroscopy and elastic-scattering spectroscopy,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 42, no. 5, p. 803, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Garcia-Uribe A, Zou J, Duvic M, Cho-Vega JH, Prieto VG, and Wang LV, “In vivo diagnosis of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer using oblique incidence diffuse reflectance spectrometry,” Cancer research, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Keller MD et al. , “Autofluorescence and diffuse reflectance spectroscopy and spectral imaging for breast surgical margin analysis,” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine: The Official Journal of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 15–23, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Spliethoff JW et al. , “Improved identification of peripheral lung tumors by using diffuse reflectance and fluorescence spectroscopy,” Lung cancer, vol. 80, no. 2, pp. 165–171, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gomes AJ, Ruderman SK, Backman V, Cruz MD, Wali RK, and Roy HK, In vivo measurement of the shape of the tissue-refractive-index correlation function and its application to detection of colorectal field carcinogenesis (no. 4). SPIE, 2012, pp. 1–9, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gurjar RS et al. , “Imaging human epithelial properties with polarized light-scattering spectroscopy,” Nature medicine, vol. 7, no. 11, pp. 1245–1248, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Siegel MP, Kim YL, Roy HK, Wali RK, and Backman V, “Assessment of blood supply in superficial tissue by polarization-gated elastic light-scattering spectroscopy,” Applied optics, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 335–342, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Backman V et al. , “Measuring cellular structure at submicrometer scale with light scattering spectroscopy,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 887–893, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Georgakoudi I et al. , “Fluorescence, reflectance, and light-scattering spectroscopy for evaluating dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus,” Gastroenterology, vol. 120, no. 7, pp. 1620–1629, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Qiu L et al. , “Multispectral scanning during endoscopy guides biopsy of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus,” Nature medicine, vol. 16, no. 5, p. 603, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Qiu L et al. , “Multispectral light scattering endoscopic imaging of esophageal precancer,” Light: Science & Applications, Article vol. 7, p. 17174, 04/06/online 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Patel M et al. , “Polarization gating spectroscopy of normal-appearing duodenal mucosa to detect pancreatic cancer,” Gastrointestinal endoscopy, vol. 80, no. 5, pp. 786–793. e2, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhang L et al. , “Light scattering spectroscopy identifies the malignant potential of pancreatic cysts during endoscopy,” Nature biomedical engineering, vol. 1, p. 0040, 03/13 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Farrell TJ, Patterson MS, and Wilson B, “A diffusion theory model of spatially resolved, steady-state diffuse reflectance for the noninvasive determination of tissue optical properties in vivo,” Medical physics, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 879–888, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zonios G et al. , “Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of human adenomatous colon polyps in vivo,” Applied Optics, vol. 38, no. 31, pp. 6628–6637, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zonios G and Dimou A, “Modeling diffuse reflectance from homogeneous semi-infinite turbid media for biological tissue applications: a Monte Carlo study,” Biomedical optics express, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 3284–3294, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mantis G and Zonios G, “Simple two-layer reflectance model for biological tissue applications,” Applied optics, vol. 48, no. 18, pp. 3490–3496, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Calabro KW and Bigio IJ, “Influence of the phase function in generalized diffuse reflectance models: review of current formalisms and novel observations,” Journal of biomedical optics, vol. 19, no. 7, p. 075005, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Morgner U et al. , “Spectroscopic optical coherence tomography,” Optics letters, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 111–113, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Robles F, Graf RN, and Wax A, “Dual window method for processing spectroscopic optical coherence tomography signals with simultaneously high spectral and temporal resolution,” Optics Express, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 6799–6812, 2009/04/13 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Robles FE, Wilson C, Grant G, and Wax A, “Molecular imaging true-colour spectroscopic optical coherence tomography,” Nature Photonics, vol. 5, p. 744, 10/23/online 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yi J and Backman V, “Imaging a full set of optical scattering properties of biological tissue by inverse spectroscopic optical coherence tomography,” Optics letters, vol. 37, no. 21, pp. 4443–4445, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yi J et al. , “Spatially resolved optical and ultrastructural properties of colorectal and pancreatic field carcinogenesis observed by inverse spectroscopic optical coherence tomography,” Journal of biomedical optics, vol. 19, no. 3, p. 036013, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhao Y, Maher JR, Kim J, Selim MA, Levinson H, and Wax A, “Evaluation of burn severity in vivo in a mouse model using spectroscopic optical coherence tomography,” Biomedical optics express, vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 3339–3345, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yi J, Wei Q, Liu W, Backman V, and Zhang HF, “Visible-light optical coherence tomography for retinal oximetry,” Optics Letters, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 1796–1798, 2013/06/01 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chong SP, Merkle CW, Leahy C, Radhakrishnan H, and Srinivasan VJ, “Quantitative microvascular hemoglobin mapping using visible light spectroscopic Optical Coherence Tomography,” Biomedical optics express, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 1429–1450, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lichtenegger A et al. , “Spectroscopic imaging with spectral domain visible light optical coherence microscopy in Alzheimer’s disease brain samples,” Biomedical optics express, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 4007–4025, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Veenstra C, Petersen W, Vellekoop IM, Steenbergen W, and Bosschaart N, “Spatially confined quantification of bilirubin concentrations by spectroscopic visible-light optical coherence tomography,” Biomedical Optics Express, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 3581–3589, 2018/08/01 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Song W, Zhou L, Zhang S, Ness S, Desai M, and Yi J, “Fiber-based visible and near infrared optical coherence tomography (vnOCT) enables quantitative elastic light scattering spectroscopy in human retina,” Biomedical Optics Express, vol. 9, no. 7, pp. 3464–3480, 2018/07/01 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kassinopoulos M, Bousi E, Zouvani I, and Pitris C, “Correlation of the derivative as a robust estimator of scatterer size in optical coherence tomography (OCT),” Biomedical optics express, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 1598–1606, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Krishnaswamy V, Laughney AM, Paulsen KD, and Pogue BW, “Dark-field scanning in situ spectroscopy platform for broadband imaging of resected tissue,” Optics letters, vol. 36, no. 10, pp. 1911–1913, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Laughney AM et al. , “Scatter Spectroscopic Imaging Distinguishes between Breast Pathologies in Tissues Relevant to Surgical Margin Assessment,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 18, no. 22, pp. 6315–6325, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Krishnaswamy V, Laughney AM, Wells WA, Paulsen KD, and Pogue BW, “Scanning in situ spectroscopy platform for imaging surgical breast tissue specimens,” Optics express, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 2185–2194, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Subramanian H et al. , “Partial-wave microscopic spectroscopy detects subwavelength refractive index fluctuations: an application to cancer diagnosis,” Optics letters, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 518–520, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Subramanian H et al. , “Optical methodology for detecting histologically unapparent nanoscale consequences of genetic alterations in biological cells,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 10.1073/pnas.0804723105 vol. 105, no. 51, p. 20118, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Subramanian H et al. , “Nanoscale cellular changes in field carcinogenesis detected by partial wave spectroscopy,” Cancer research, vol. 69, no. 13, pp. 5357–5363, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Backman V and Roy HK, “Light-scattering technologies for field carcinogenesis detection: a modality for endoscopic prescreening,” Gastroenterology, vol. 140, no. 1, pp. 35–41. e5, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kim JS, Pradhan P, Backman V, and Szleifer I, “The influence of chromosome density variations on the increase in nuclear disorder strength in carcinogenesis,” Physical biology, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 015004, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Damania D et al. , “Role of cytoskeleton in controlling the disorder strength of cellular nanoscale architecture,” Biophysical journal, vol. 99, no. 3, pp. 989–996, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mourant JR, Freyer JP, Hielscher AH, Eick AA, Shen D, and Johnson TM, “Mechanisms of light scattering from biological cells relevant to noninvasive optical-tissue diagnostics,” Appl Opt, vol. 37, no. 16, pp. 3586–93, June 1 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Drezek R, Dunn A, and Richards-Kortum R, “Light scattering from cells: finite-difference time-domain simulations and goniometric measurements,” Appl Opt, vol. 38, no. 16, pp. 3651–61, June 1 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Mourant JR, Johnson TM, Carpenter S, Guerra A, Aida T, and Freyer JP, “Polarized angular dependent spectroscopy of epithelial cells and epithelial cell nuclei to determine the size scale of scattering structures,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 378–87, July 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Mourant JR, Johnson TM, Doddi V, and Freyer JP, “Angular dependent light scattering from multicellular spheroids,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 93–9, January 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ceolato R, Riviere N, Jorand R, Ducommun B, and Lorenzo C, “Light-scattering by aggregates of tumor cells: Spectral, polarimetric, and angular measurements,” (in English), Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy & Radiative Transfer, vol. 146, pp. 207–213, October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Lin X, Wan N, Weng L, and Zhou Y, “Angular-dependent light scattering from cancer cells in different phases of the cell cycle,” Appl Opt, vol. 56, no. 29, pp. 8154–8158, October 10 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Roy HK et al. , “Four-dimensional elastic light-scattering fingerprints as preneoplastic markers in the rat model of colon carcinogenesis,” Gastroenterology, vol. 126, no. 4, pp. 1071–81; discussion 948, April 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ho D, Drake TK, Bentley RC, Valea FA, and Wax A, “Evaluation of hybrid algorithm for analysis of scattered light using ex vivo nuclear morphology measurements of cervical epithelium,” Biomedical optics express, vol. 6, no. 8, pp. 2755–2765, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Steelman ZA, Eldridge WJ, and Wax A, “Response to Comment on “Is the nuclear refractive index lower than cytoplasm? Validation of phase measurements and implications for light scattering technologies”,” Journal of biophotonics, vol. 11, no. 6, p. e201800091, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Steelman ZA, Eldridge WJ, Weintraub JB, and Wax A, “Is the nuclear refractive index lower than cytoplasm? Validation of phase measurements and implications for light scattering technologies,” Journal of Biophotonics, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Drezek R et al. , “Light scattering from cervical cells throughout neoplastic progression: influence of nuclear morphology, DNA content, and chromatin texture,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 7–16, January 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Arifler D, Guillaud M, Carraro A, Malpica A, Follen M, and Richards-Kortum R, “Light scattering from normal and dysplastic cervical cells at different epithelial depths: finite-difference time-domain modeling with a perfectly matched layer boundary condition,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 484–94, July 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Krakiwsky SE, Turner LE, and Okoniewski MM, “Graphics processor unit (GPU) acceleration of finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) algorithm,” (in English), 2004 Ieee International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Vol 5, Proceedings, pp. 265–268, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Nagaoka T and Watanabe S, “A GPU-Based Calculation Using the Three-Dimensional FDTD Method for Electromagnetic Field Analysis,” (in English), 2010 Annual International Conference of the Ieee Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (Embc), pp. 327–330, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Nagaoka T and Watanabe S, “Accelerating Three-Dimensional FDTD Calculations on GPU Clusters for Electromagnetic Field Simulation,” (in English), 2012 Annual International Conference of the Ieee Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (Embc), pp. 5691–5694, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Lin X, Wan N, Weng L, and Zhou Y, “Light scattering from normal and cervical cancer cells,” Appl Opt, vol. 56, no. 12, pp. 3608–3614, April 20 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Hsu WC, Su JW, Chang CC, and Sung KB, “Investigating the backscattering characteristics of individual normal and cancerous cells based on experimentally determined three-dimensional refractive index distributions,” (in English), Optics in Health Care and Biomedical Optics V, vol. 8553, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [76].Arifler D, Pavlova I, Gillenwater A, and Richards-Kortum R, “Light scattering from collagen fiber networks: micro-optical properties of normal and neoplastic stroma,” Biophys J, vol. 92, no. 9, pp. 3260–74, May 1 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Arifler D, Macaulay C, Follen M, and Guillaud M, “Numerical investigation of two-dimensional light scattering patterns of cervical cell nuclei to map dysplastic changes at different epithelial depths,” Biomed Opt Express, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 485–98, February 1 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Kim YL et al. , “Simultaneous Measurement of Angular and Spectral Properties of Light Scattering for Characterization of Tissue Microarchitecture and Its Alteration in Early Precancer,” Ieee Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 243–256, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [79].Gomes AJ et al. , “Rectal mucosal microvascular blood supply increase is associated with colonic neoplasia,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 15, no. 9, pp. 3110–3117, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Wax A et al. , “Cellular organization and substructure measured using angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry,” Biophysical journal, vol. 82, no. 4, pp. 2256–2264, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Pyhtila J, Graf R, and Wax A, “Determining nuclear morphology using an improved angle-resolved low coherence interferometry system,” Opt Express, vol. 11, no. 25, pp. 3473–84, December 15 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Wax A et al. , Prospective grading of neoplastic change in rat esophagus epithelium using angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry (no. 5). SPIE, 2005, pp. 1–10, 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Terry NG et al. , “Detection of Dysplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus With Angle-Resolved Low Coherence Interferometry,” (in English), Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, vol. 71, no. 5, pp. Ab121–Ab122, April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [84].Terry NG et al. , “Detection of Dysplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus With In Vivo Depth-Resolved Nuclear Morphology Measurements,” (in English), Gastroenterology, vol. 140, no. 1, pp. 42–50, January 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Terry N et al. , “Detection of intestinal dysplasia using angle-resolved low coherence interferometry,” (in English), Journal of Biomedical Optics, vol. 16, no. 10, October 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Ho D, Drake TK, Smith-McCune KK, Darragh TM, Hwang LY, and Wax A, “Feasibility of clinical detection of cervical dysplasia using angle-resolved low coherence interferometry measurements of depth-resolved nuclear morphology,” (in English), International Journal of Cancer, vol. 140, no. 6, pp. 1447–1456, March 15 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Steelman ZA, Ho D, Chu KK, and Wax A, “Scanning system for angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry,” (in English), Optics Letters, vol. 42, no. 22, pp. 4581–4584, November 15 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Kim S et al. , “Analyzing spatial correlations in tissue using angle-resolved low coherence interferometry measurements guided by co-located optical coherence tomography,” Biomed Opt Express, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 1400–14, April 1 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Amoozegar C, Giacomelli MG, Keener JD, Chalut KJ, and Wax A, “Experimental verification of T-matrix-based inverse light scattering analysis for assessing structure of spheroids as models of cell nuclei,” Appl Opt, vol. 48, no. 10, pp. D20–5, April 1 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Giacomelli M, Zhu Y, Lee J, and Wax A, “Size and shape determination of spheroidal scatterers using two-dimensional angle resolved scattering,” Opt Express, vol. 18, no. 14, pp. 14616–26, July 5 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Yu H, Park H, Kim Y, Kim MW, and Park Y, “Fourier-transform light scattering of individual colloidal clusters,” Optics Letters, vol. 37, no. 13, pp. 2577–2579, 2012/07/01 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Cuccia DJ, Bevilacqua F, Durkin AJ, Ayers FR, and Tromberg BJ, “Quantitation and mapping of tissue optical properties using modulated imaging,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 024012, Mar-Apr 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Popescu G, Ikeda T, Dasari RR, and Feld MS, “Diffraction phase microscopy for quantifying cell structure and dynamics,” Opt Lett, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 775–7, March 15 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Jo Y et al. , “Angle-resolved light scattering of individual rod-shaped bacteria based on Fourier transform light scattering,” Sci Rep, vol. 4, p. 5090, May 28 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Jo Y, Jung J, Kim MH, Park H, Kang SJ, and Park Y, “Label-free identification of individual bacteria using Fourier transform light scattering,” Opt Express, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 15792–805, June 15 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Mir M et al. , “Label-free characterization of emerging human neuronal networks,” Sci Rep, vol. 4, p. 4434, March 24 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Zheng J-Y, Pasternack RM, and Boustany NN, “Optical Scatter Imaging with a digital micromirror device,” Optics Express, vol. 17, no. 22, pp. 20401–20414, 2009/10/26 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Pasternack RM, Zheng J-Y, and Boustany NN, “Optical scatter changes at the onset of apoptosis are spatially associated with mitochondria,” Journal of Biomedical Optics, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 040504, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Ding H, Nguyen F, Boppart SA, and Popescu G, “Optical properties of tissues quantified by Fourier-transform light scattering,” Opt Lett, vol. 34, no. 9, pp. 1372–4, May 1 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Lee M et al. , “Label-free optical quantification of structural alterations in Alzheimer’s disease,” Sci Rep, vol. 6, p. 31034, August 3 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Cuccia DJ, Bevilacqua F, Durkin AJ, and Tromberg BJ, “Modulated imaging: quantitative analysis and tomography of turbid media in the spatial-frequency domain,” Opt Lett, vol. 30, no. 11, pp. 1354–6, June 1 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Gioux S et al. , “First-in-human pilot study of a spatial frequency domain oxygenation imaging system,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 16, no. 8, p. 086015, August 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Ponticorvo A, Burmeister DM, Yang B, Choi B, Christy RJ, and Durkin AJ, “Quantitative assessment of graded burn wounds in a porcine model using spatial frequency domain imaging (SFDI) and laser speckle imaging (LSI),” Biomed Opt Express, vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 3467–81, October 1 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Yafi A et al. , “Quantitative skin assessment using spatial frequency domain imaging (SFDI) in patients with or at high risk for pressure ulcers,” Lasers Surg Med, vol. 49, no. 9, pp. 827–834, November 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Travers JB et al. , “Noninvasive mesoscopic imaging of actinic skin damage using spatial frequency domain imaging,” Biomed Opt Express, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 3045–3052, June 1 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Rohrbach DJ et al. , “Preoperative mapping of nonmelanoma skin cancer using spatial frequency domain and ultrasound imaging,” Acad Radiol, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 263–70, February 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].McClatchy DM et al. , “Light scattering measured with spatial frequency domain imaging can predict stromal versus epithelial proportions in surgically resected breast tissue,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 1–11, September 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Lin AJ et al. , “Spatial frequency domain imaging of intrinsic optical property contrast in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease,” Ann Biomed Eng, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 1349–57, April 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Singh-Moon RP, Roblyer DM, Bigio IJ, and Joshi S, “Spatial mapping of drug delivery to brain tissue using hyperspectral spatial frequency-domain imaging,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 19, no. 9, p. 96003, September 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Wilson RH et al. , “High-speed spatial frequency domain imaging of rat cortex detects dynamic optical and physiological properties following cardiac arrest and resuscitation,” Neurophotonics, vol. 4, no. 4, p. 045008, October 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Kanick SC, McClatchy DM, Krishnaswamy V, Elliott JT, Paulsen KD, and Pogue BW, “Sub-diffusive scattering parameter maps recovered using wide-field high-frequency structured light imaging,” Biomedical optics express, vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 3376–3390, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Almassalha LM et al. , “Label-free imaging of the native, living cellular nanoarchitecture using partial-wave spectroscopic microscopy,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, no. 42, pp. E6372–E6381, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Schürmann M, Scholze J, Müller P, Guck J, and Chan CJ, “Cell nuclei have lower refractive index and mass density than cytoplasm,” Journal of biophotonics, vol. 9, no. 10, pp. 1068–1076, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Brunsting A and Mullaney PF, “Differential light scattering from spherical mammalian cells,” Biophysical journal, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 439, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Meyer RA and Brunsting A, “Light scattering from nucleated biological cells,” Biophysical journal, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 191–203, 1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Sung Y, Choi W, Fang-Yen C, Badizadegan K, Dasari RR, and Feld MS, “Optical diffraction tomography for high resolution live cell imaging,” Optics express, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 266–277, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Choi W et al. , “Tomographic phase microscopy,” Nature methods, vol. 4, no. 9, p. 717, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Eldridge WJ, Steelman ZA, Loomis B, and Wax A, “Optical Phase Measurements of Disorder Strength Link Microstructure to Cell Stiffness,” Biophysical Journal, vol. 112, no. 4, pp. 692–702, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Marquet P et al. , “Digital holographic microscopy: a noninvasive contrast imaging technique allowing quantitative visualization of living cells with subwavelength axial accuracy,” Optics Letters, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 468–470, 2005/03/01 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Skacel M, Petras RE, Gramlich TL, Sigel JE, Richter JE, and Goldblum JR, “The diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus and its implications for disease progression,” The American journal of gastroenterology, vol. 95, no. 12, p. 3383, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Benaglia T, Sharples LD, Fitzgerald RC, and Lyratzopoulos G, “Health benefits and cost effectiveness of endoscopic and nonendoscopic cytosponge screening for Barrett’s esophagus,” Gastroenterology, vol. 144, no. 1, pp. 62–73. e6, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Movasaghi Z, Rehman S, and Rehman IU, “Raman spectroscopy of biological tissues,” Applied Spectroscopy Reviews, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 493–541, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [123].Hanlon E et al. , “Prospects for in vivo Raman spectroscopy,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 45, no. 2, p. R1, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Schut TCB et al. , “Discriminating basal cell carcinoma from its surrounding tissue by Raman spectroscopy,” Journal of Investigative Dermatology, vol. 119, no. 1, pp. 64–69, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Scarcelli G and Yun SH, “Multistage VIPA etalons for high-extinction parallel Brillouin spectroscopy,” Optics express, vol. 19, no. 11, pp. 10913–10922, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Traverso AJ, Thompson JV, Steelman ZA, Meng Z, Scully MO, and Yakovlev VV, “Dual Raman-Brillouin microscope for chemical and mechanical characterization and imaging,” Analytical chemistry, vol. 87, no. 15, pp. 7519–7523, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Meng Z, Traverso AJ, Ballmann CW, Troyanova-Wood MA, and Yakovlev VV, “Seeing cells in a new light: a renaissance of Brillouin spectroscopy,” Advances in Optics and Photonics, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 300–327, 2016. [Google Scholar]