Abstract

In this paper, we aim to underscore the need for a more nuanced understanding of vaccine non-adopters. As the availability of vaccines does not translate into their de facto adoption—a phenomenon that may be more pronounced amid “Operation Warp Speed”—it is important for public health professionals to thoroughly understand their “customers” (i.e., end users of COVID-19 vaccines) to ensure satisfactory vaccination rates and to safeguard society at large.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Vaccination, Vaccines, Vaccine hesitancy, Vaccine non-adopters

Graphical abstract

A cure for COVID-19 is urgently needed. As COVID-19 outbreaks of various sizes and the public outcry over social and economic freedom have become the “new normal,” it is clear that physical contact–limiting mechanisms such as lockdowns, self-isolation, and social distancing are not sustainable long-term countermeasures against the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It has become even clearer that non-pharmaceutical interventions like social distancing are contingency plans; a cure for the ever-spreading COVID-19 pandemic is expected elsewhere, most probably in pharmaceutical solutions like COVID-19 vaccines. High hopes are being placed on COVID-19 vaccines with the potential to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus and, in turn, prevent societies across the world from facing ongoing COVID-19 incidence and deaths. The plan is simple: develop a vaccine and possibly save the world. With a pronounced need for vaccines to halt the spread of COVID-19, talents established and new, R&D resources private and public, and support local and international are bound by the same shared, determined, and fervent desire to see the world vaccinated and return to “normal.”

Time is of the essence. Although the name “Operation Warp Speed” refers specifically to America’s COVID-19 vaccine programs, speed has been the focus of most (Mullard, 2020), if not all, such programs since their inception in a race for the first approved COVID-19 vaccine. Yet in the midst of a global health crisis, few seem to have considered COVID-19 vaccines, which are essentially consumer health products (Su et al., 2019), in the context of the classic supply-demand economic model. Much of the world has been concentrating on developing a vaccine, representing the supply side of the equation. Meanwhile, not enough questions are being asked from the demand side: who are the potential consumers of COVID-19 vaccines? Though many vaccine programs, whether initiated by non-profit or for-profit pharmaceutical companies, are government-sponsored, funding from governmental agencies only indicates that these agencies are purchasers or direct customers of potential vaccines; they are not the same as end users or fundamental consumers. In other words, although governmental demand for COVID-19 vaccines has been most noticeable, it is individual citizens who will be receiving these vaccines (i.e., end users). This understanding has many implications, one of which centres on the need for a common advertising or marketing practice—consumer analysis.

As the literature indicates, when it comes to end users of consumer health technologies such as vaccines, their attitudes, knowledge, and intentions to adopt a COVID-19 vaccine vary greatly (World Health Organization, 2014). A joint study conducted by the Associated Press and the University of Chicago (AP-NORC) in May 2020 showed that COVID-19 vaccine availability would not translate into vaccine adoption for 51% of Americans surveyed (The Associated Press-, 2020). Among these vaccine non-adopters, 31% were hesitant about adopting a COVID-19 vaccine, whereas 1 in 5 said they would refuse the vaccine outright (The Associated Press-, 2020). These findings resonate with the results of an early study conducted by a group of French scientists in March 2020, who found that among a representative sample of the French population, 26% indicated they would refuse a COVID-19 vaccine once it becomes available (roup and A future v, 2020). Furthermore, despite being particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, non-adoption rates among people of low socioeconomic status are even more alarming: approximately 37% stated they would refuse a COVID-19 vaccine regardless of availability (roup and A future v, 2020). As disturbing as they may be, these findings are hardly surprising (The Lancet and Looking beyon, 2018). Research suggests that across infectious disease contexts and vaccine types, vaccine non-adopters (often characterised as expressing “vaccine hesitancy”) are prevalent (World Health Organization, 2014; The Lancet and Looking beyon, 2018; Larson et al., 2007).

Vaccine hesitancy poses a substantial threat to global health and is a top 10 priority of the World Health Organization (WHO) (World Health Organization, 2019a). Per the WHO, this phenomenon refers to “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services” (World Health Organization, 2015). Within the vaccine-related literature, vaccine hesitancy is among the limited terms available that centres on the demand rather than supply side of vaccine adoption. In theory, the term “vaccine hesitancy” should capture only one aspect (i.e., reluctance) of vaccine consumers’ nuanced rationale for being vaccine non-adopters. The crux of this issue is that “vaccine hesitancy” in fact covers myriad distinctive reasons for vaccine non-adoption, ranging from delay to indecision to reluctance to refusal. In other words, the term can be used to represent a considerable proportion of vaccine non-adopters without paying mind to these potential consumers’ distinct traits. Therefore, the effectiveness of this definition is questionable in terms of helping health experts better understand vaccine non-adopters’ unique concerns about COVID-19 vaccines to address these anxieties accordingly.

A more accurate term to refer to people who do not adopt vaccines is “vaccine non-adopters.” Vaccine non-adopters are not one group of individuals but rather encompass many groups who possess distinct reasons for vaccine non-adoption (World Health Organization, 2014). Some vaccine non-adopters may be highly informed about vaccine efficacy and safety, such as the efficacy of established vaccines like the flu vaccine, and decide not to get vaccinated (Su et al., 2019). Other vaccine non-adopters might choose not to get vaccinated because they do not realise they must receive the vaccine to be protected from contracting SARS-CoV-2 (roup and A future v, 2020). It is important to note that some non-adoption decisions made by vaccine non-adopters could be based on justified considerations (The Associated Press-, 2020), such as individuals who are allergic to egg proteins (Centers for Disease Contr, 2020). Take influenza vaccines for instance. Though some influenza vaccines do not contain egg proteins and the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, for instance, no longer recommends that people with egg allergies need to be observed for an allergic reaction for 30 min, people who are allergic to egg proteins still need to be vaccinated in an inpatient or outpatient medical setting (Centers for Disease Contr, 2020). A recent study further shows that the risk of anaphylaxis, a severe case of vaccine hypersensitivity to allergens ranging from egg proteins, adjuvants, preservatives, to extrinsic substances, after all vaccines is estimated to be 1.31 per million vaccine shots (McNeil and DeStefano, 2018). While anaphylaxis cases might be alarming from the vaccine hesitants’ perspective (McNeil and DeStefano, 2018), it is important to note that vaccines prevent approximately 2–3 million deaths every year (World Health Organization, 2019b). It is expected that COVID-19 vaccines will save a markedly greater number of lives amid and beyond the pandemic (Yamey et al., 2020; Lurie et al., 2020; Thanh Le et al., 2020; Graham, 2020).

Overall, it is imperative for health experts to understand that vaccine hesitants’ cost-analysis of vaccination adoption may be drastically different, and perhaps most importantly, may not be accurately grounded in evidence (The Associated Press-, 2020; roup and A future v, 2020), where even though a vaccine could save lives, livelihoods, and GDPs (Yamey et al., 2020; Lurie et al., 2020; Thanh Le et al., 2020; Graham, 2020), an extremely low probability of vaccine-related adverse effect may hinder their adoption behaviours (Opri et al., 2018). For people who have egg allergies or those who perceive they may have a hypersensitive reactions to vaccines without any clinical foundations (Opri et al., 2018), regardless of whether a COVID-19 vaccine contains egg proteins, how soon it becomes available, or how safe and effective it may be, they may still be reluctant to adopt the vaccine because the perceived personal health-related risks (i.e., an allergic reaction) outweigh the proposed potential benefits (i.e., protection from the virus). Thus, it is important for health experts to communicate safety measures in an informative as well as persuasive manner (Noar et al., 2009), in order to effectively clear these vaccine hesitants’ unjustified doubts. This is particularly relevant, as based on available evidence (Lurie et al., 2020; Thanh Le et al., 2020; Graham, 2020), the majority of COVID-19 vaccines may not contain egg proteins in the first place—it is of paramount importance for health experts to deliver their evidence-based educational messages to vaccine hesitants before anti-vaxxers’ COVID-19 misinformation or disinformation does (see Graph 1).

Other potential vaccine consumers decide not to receive vaccines for non-scientific reasons. This group includes vaccine conspiracy theorists (World Health Organization, 2014), whose beliefs may be instigated by deliberate misinformation or disinformation campaigns or by the current COVID-19 infodemic. Their conviction can further fuel unfounded, toxic narratives surrounding COVID-19 and associated vaccines in the absence of timely intervention. For health experts to dispel these vaccine conspirators’ groundless beliefs and mitigate the adverse effects of the COVID-19 infodemic on COVID-19 vaccine adoption, experts must first understand who these people are. More specifically, simply labelling these individuals “vaccine non-adopters” or “hesitants” may be insufficient in providing health experts an exact, actionable understanding of vaccine non-adopters for subsequent campaign intervention design and development.

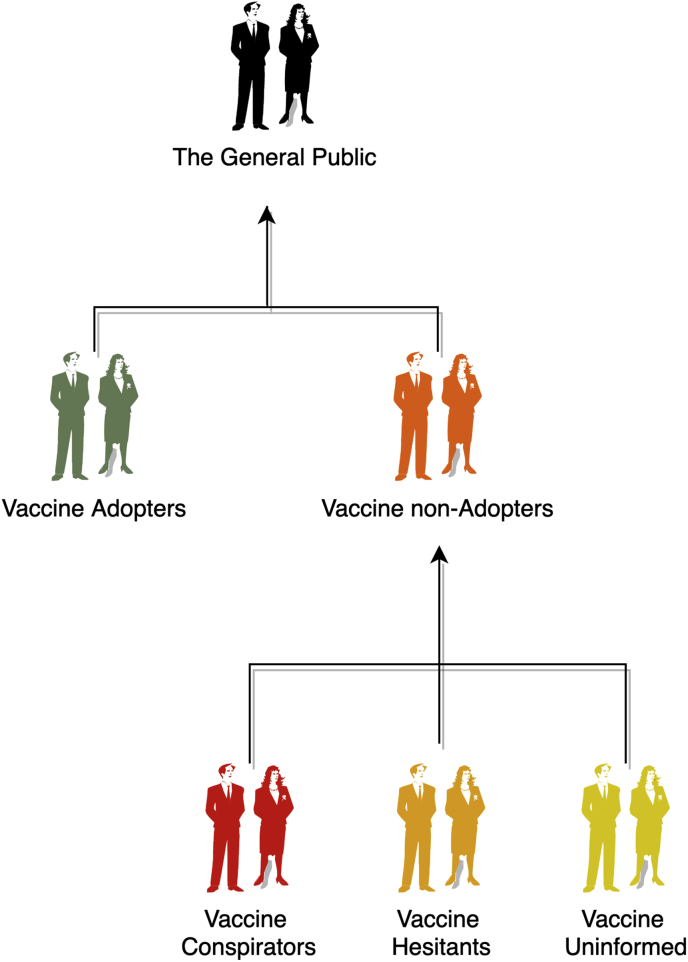

Rather than using the terms “vaccine non-adopters” and “vaccine hesitants” interchangeably, health experts can consider adopting a more precise classification of vaccine non-adopters, such as “vaccine conspirators” (people who possess too much misinformation to adopt the vaccine), “vaccine uninformed” (people who possess insufficient information to adopt the vaccine), and “vaccine hesitants” (people who are considering adopting the vaccine but lack the right conditions or context to do so) (see Fig. 1). Instead of presenting a definitive, authoritative classification of vaccine non-adopters, this categorisation is intended to serve as inspiration for health experts and communication professionals. Educating three groups of vaccine non-adopters with unique traits, rather than a single large group of vaccine non-adopters with overlapping features, may be more cost-effective in terms of educational materials design, communication between interventionists and their audiences, and evaluation of intervention outcomes.

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of vaccine adopters and non-adopters.

Ultimately, for health experts or communication professionals to develop effective communication guidelines and campaign interventions to promote COVID-19 vaccine adoption, they first need to obtain a fine-grained understanding of their target audiences or customers. After all, the term “vaccine non-adopters” encompasses a large group of people from diverse backgrounds (Larson et al., 2007), including well-educated individuals without vaccine-related allergies who may still refuse to adopt a COVID-19 vaccine. To ensure that meaningful population-level SARS-CoV-2 immunity can be achieved with the help of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines, policymakers, health experts, and health communication professionals should, first and foremost, understand the many characteristics of vaccine non-adopters and develop tailored communication strategies and campaign deliverables. Considering the potentially grave health and financial consequences of an unvaccinated majority once COVID-19 vaccines become available, a race for a better understanding of the characteristics of COVID-19 vaccine non-adopters is needed—perhaps as urgently, if not more so, as the race for effective vaccines.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Contributor Information

Zhaohui Su, Email: szh@utexas.edu.

Jun Wen, Email: j.wen@ecu.edu.au.

Jaffar Abbas, Email: Abbas512@sjtu.edu.cn.

Dean McDonnell, Email: dean.mcdonnell@itcarlow.ie.

Ali Cheshmehzangi, Email: Ali.Cheshmehzangi@nottingham.edu.cn.

Xiaoshan Li, Email: xiaoshan.li@utexas.edu.

Junaid Ahmad, Email: Jahmad@piph.prime.edu.pk.

Sabina Šegalo, Email: sabina.segalo11@gmail.com.

Daniel Maestro, Email: danielmaestrobih@gmail.com.

Yuyang Cai, Email: caiyuyang@sjtu.edu.cn.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Flu Vaccine and People with Egg Allergies.https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/egg-allergies.htm [Google Scholar]

- Graham B.S. Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development. Science. 2020;368(6494):945. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson H.J. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature. Vaccine. 2007;32(19):2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie N. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(21):1969–1973. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil M.M., DeStefano F. Vaccine-associated hypersensitivity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018;141(2):463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullard A. COVID-19 vaccine development pipeline gears up. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1751–1752. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar S.M., Harrington N.G., Aldrich R.S. The role of message tailoring in the development of persuasive health communication messages. Annals of the International Communication Association. 2009;33(1):73–133. [Google Scholar]

- Opri R. True and false contraindications to vaccines. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2018;46(1):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCONEL Group A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(7):769–770. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30426-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z., Chengbo Z., Mackert M. Understanding the influenza vaccine as a consumer health technology: a structural equation model of motivation, behavioral expectation, and vaccine adoption. J. Commun. Healthc. 2019;12(3–4):170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh Le T. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19(5):305–306. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The associated press-NORC center for public affairs research, Expectations for a COVID-19 vaccine, in COVID-19. 2020, The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

- The Lancet, Looking beyond the decade of vaccines. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2139. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32862-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2014. Appendices to the Report of the Sage Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2015. Summary WHO SAGE Conclusions and Recommendations on Vaccine Hesitancy. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2019. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019.https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccines. 2019. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/emergencies/travel-advice/ith-travel-chapter-6-vaccines.pdf?sfvrsn=285473b4_4

- Yamey G. Ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1405–1406. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30763-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]