Abstract

Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), caused by the free-living ameba Naegleria fowleri, has a fatality rate of over 97%. Treatment of PAM relies on amphotericin B in combination with other drugs, but few patients have survived with the existing drug treatment regimens. Therefore, development of effective drugs is a critical unmet need to avert deaths from PAM. Since ergosterol is one of the major sterols in the membrane of N. fowleri, disruption of isoprenoid and sterol biosynthesis by small-molecule inhibitors may be an effective intervention strategy against N. fowleri. The genome of N. fowleri contains a gene encoding HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR); the catalytic domains of human and N. fowleri HMGR share <60% sequence identity with only two amino acid substitutions in the active site of the enzyme. Considering the similarity of human and N. fowleri HMGR, we tested well-tolerated and widely used HMGR inhibitors, known as cholesterol-lowering statins, against N. fowleri. We identified blood-brain-barrier-permeable pitavastatin as a potent amebicidal agent against the U.S., Australian, and European strains of N. fowleri. Pitavastatin was equipotent to amphotericin B against the European strain of N. fowleri; it killed about 80% of trophozoites within 16 h of drug exposure. Pretreatment of trophozoites with mevalonate, the product of HMGR, rescued N. fowleri from inhibitory effects of statins, demonstrating that HMGR of N. fowleri is the target of statins. Because of the good safety profile and availability for both adult and pediatric uses, consideration should be given to repurposing the fast-acting pitavastatin for the treatment of PAM.

Keywords: free-living ameba, Naegleria fowleri, drug, primary amebic meningoencephalitis, statins, HMG-CoA reductase

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is a brain infection caused by the free-living ameba Naegleria fowleri, resulting in extensive inflammation of brain tissue and almost always leading to death [within 1–18 (median 5) days after symptoms begin]. In the United States, there are 145 documented cases averaging from 0 to 8 cases per year.1 Although N. fowleri infection has low prevalence, the importance of this high-consequence pathogen is underscored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)’s listing of N. fowleri as a water-safety-threatening priority biodefense pathogen.

Trophozoites are the infective form of N. fowleri. PAM occurs when water containing trophozoites enters the body through the nose. The trophozoites first attach to the nasal mucosa and then move along the olfactory nerve via the cribriform plate, until they reach the subarachnoid space and continue to the brain parenchyma.2 The destruction of host nerves and the subsequent damage of tissues in the central nervous system result in a fulminating hemorrhagic meningoencephalitis known as primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).3

The initial symptoms of PAM are similar to those produced by bacterial meningitis including fever, headache, photophobia, nausea, and vomiting with progression to seizures, confusion, coma, and death within 1 to 18 days.4 The treatment for PAM recommended by CDC guidance is amphotericin B, azithromycin, fluconazole, rifampicin, and miltefosine, based on a few successfully treated cases.5 In spite of this recommended treatment, more than 97% of all patients treated with this drug regimen have not survived. Thus, there is a need to investigate and develop new drugs against N. fowleri. Drug discovery for PAM has been hindered because of the lack of identification of druggable targets. Despite advances in molecular biology and bioinformatic tools, few druggable targets (e.g., pore forming protein, cysteine protease, CYP51, 24-SMT, ERG2) were identified in N. fowleri.6-11 In this in vitro study, we focused on mechanism-based discovery of new anti-Naegleria compounds by identifying a gene encoding HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR) in the genome of N. fowleri, investigating the effect of HMGR inhibitors (also known as statins) on growth inhibition of N. fowleri, examining the killing effect of the most potent amebicidal statin at different time points, and lastly, evaluating the on-target activity of the statins in N. fowleri.

RESULTS

Homology Modeling of HMGR of N. fowleri.

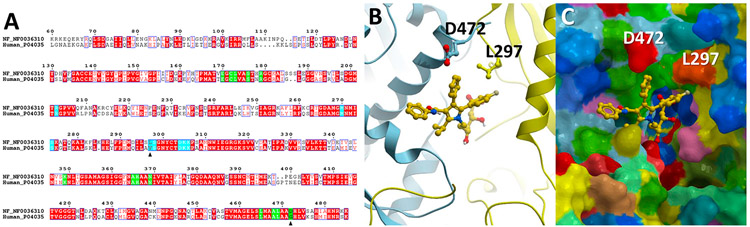

The catalytic domain of human and N. fowleri HMGR share <60% sequence identity (Figure 1A). Using atomic coordinates for the human HMGR catalytic domain bound to atorvastatin (marketed under the trade name Lipitor; PDB ID 1HWK), we generated a 3-D homology model of the N. fowleri enzyme and analyzed the statin binding site. The statin binding site is located at the homodimer interface formed by the HMGR monomers colored yellow and cyan in Figure 1B. Among the 21 residues directly contacting Lipitor, two are variable (Figure 1A). Two substitutions, including G → 472D and V → 297L, are present in N. fowleri HMGR (Figure 1C). The finding of only two amino acid substitutions between the human HMGR and N. fowleri HMGR active site, led us to attempt repurposing of approved statins against N. fowleri.

Figure 1.

Homology modeling of HMGR of N. fowleri. (A) Alignments between the human and N. fowleri HMGR catalytic domains. Invariant residues are in red; amino acids within 3.5 Å of Lipitor are highlighted in green or cyan, depending on the identity of the HMGR monomers forming a dimer interface where statins bind. Black triangles point at the variable positions in the Lipitor binding site. (B) Ribbon representation of the HMGR dimer interface with Lipitor (yellow sticks) bound. Protein monomers are shown as blue and yellow ribbons. Variable residues, L297 and D472, are in sticks. (C) Space-filled representation of the protein surface with the bound Lipitor. Yellow or cyan colors on the surface highlight protein backbones, while amino acid side chains are colored according to the physicochemical priorities: positively charged in blue, negatively charged in red, aliphatic in ochre, hydrophilic neutral in green, aromatic in dark cyan.

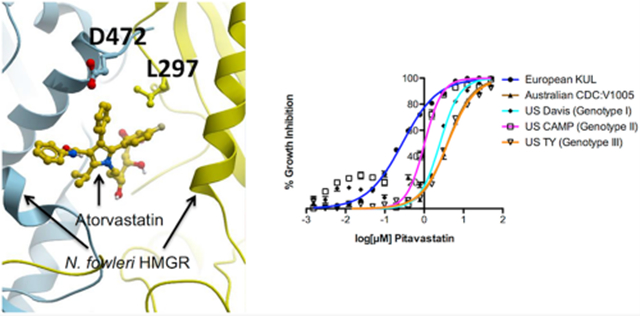

In Vitro Activity of HMGR Inhibitors against N. fowleri.

We first validated the utility of the statins as amebicidal drugs by determining the EC50 of seven statins (fluvastatin, atorvastatin, simvastatin, rosuvastatin, metavastatin, pitavastatin, and pravastatin) against N. fowleri trophozoites of our laboratory reference European KUL strain. The EC50 values of statins ranged between 0.3 and 19 μM, with pitavastatin the most potent against KUL trophozoites (Table 1). Two other statins, fluvastatin and rosuvastatin, ranked second and third in potency against the KUL strain. Since strains of different genotypes of N. fowleri show variable susceptibility to drugs,12 we tested the susceptibility of different genotypes to the three highly active statins, pitavastatin, fluvastatin, and rosuvastatin. While the European KUL strain was susceptible to rosuvastatin, with an EC50 of 1.4 μM, strains belonging to U.S. genotypes I (Davis) and II (CAMP) were about 3-fold less susceptible to rosuvastatin than KUL. Both Australian (CDC:V1005) and U.S. genotype III (TY) strains were least susceptible to rosuvastatin and exhibited an EC50 of about 22 and 17 μM, respectively (Table 1). Although fluvastatin exhibited an EC50 in the nanomolar range against KUL strain (0.7 μM), other strains were not equally susceptible to fluvastatin, and the EC50 of fluvastatin varied widely from 2 μM to 24 μM (Table 1). Pitavastatin was equipotent to the standard of care amphotericin B and 180-fold more potent than miltefosine against European KUL strain. Although the EC50 of pitavastatin against other strains was 3- to 12-fold higher than the EC50 of KUL (0.3 μM), all U.S. and Australian strains were almost equally susceptible to pitavastatin and maintained an EC50 within a narrow range of 1–4 μM (Table 1).

Table 1.

EC50 Values of Different Statins against Different Strains of N. fowleri

| EC50 (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | strain | mean | 95% lower CLa | 95% upper CLa |

| atorvastatin | European KUL | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| mevastatin | European KUL | 4.4 | 3.8 | 5.2 |

| pravastatin | European KUL | 19.1 | 18.2 | 20.2 |

| simvastatin | European KUL | 4.4 | 4.1 | 4.6 |

| rosuvastatin | European KUL | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| Australian CDC:V1005 | 22.1 | 19.3 | 25.3 | |

| U.S. Davis (Genotype I) | 4.5 | 3.8 | 5.4 | |

| U.S. CAMP (Genotype II) | 4.6 | 4.2 | 5.1 | |

| U.S. TY (Genotype III) | 16.7 | 15.2 | 18.3 | |

| fluvastatin | European KUL | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Australian CDC:V1005 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 5.4 | |

| U.S. Davis (Genotype I) | 10.2 | 8.1 | 13 | |

| U.S. CAMP (Genotype II) | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.4 | |

| U.S. TY (Genotype III) | 24.2 | 20.1 | 29.2 | |

| pitavastatin | European KUL | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Australian CDC:V1005 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 4.7 | |

| U.S. Davis (Genotype I) | 2.5 | 2.1 | 3 | |

| U.S. CAMP (Genotype II) | 1 | 0.8 | 1.3 | |

| U.S. TY (Genotype III) | 4 | 3.7 | 4.3 | |

| Standards of care | ||||

| amphotericin B15 | European KUL | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.1 |

| Australian CDC:V1005 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| U.S. Davis (Genotype I) | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| U.S. CAMP (Genotype II) | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| U.S. TY (Genotype III) | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| Miltefosine15 | European KUL | 54.5 | 51.4 | 57.8 |

| Australian CDC:V1005 | 15.9 | 10.3 | 24.7 | |

| U.S. Davis (Genotype I) | 58.9 | 41.3 | 83.9 | |

| U.S. CAMP (Genotype II) | 21.8 | 19.9 | 23.8 | |

| U.S. TY (Genotype III) | 37.7 | 33.1 | 43 | |

CL = confidence limit.

Since pitavastatin is an FDA-approved cholesterol-lowering drug, its activity against multiple human cell lines is well documented. Pitavastatin did not exhibit toxicity when tested at 10 μM against human T lymphocytes.13 It showed an EC50 of about 20 μM to HepG2 and HEK293 cells.14 This provides selectivity indices of pitavastatin against HepG2 and HEK293 cells ranging from 5 to 67, depending on the strain of N. fowleri used in the study.

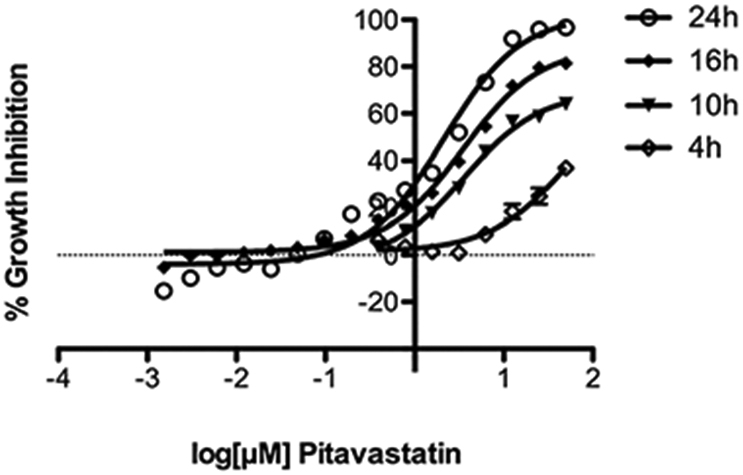

Growth Inhibition as a Function of Time.

To determine how fast pitavastatin kills N. fowleri, we measured N. fowleri growth inhibition dose–response (EC50) to pitavastatin at 4, 10, 16, and 24 h of pitavastatin exposure in triplicate in three independent experiments. Growth inhibition curves (Figure 2) demonstrate >60% growth inhibition by pitavastatin at the highest concentration as early as 10 h postexposure. Inhibition reaches 81% at 16 h postexposure (EC50 of 3.6 μM) and 96% at 24 h (EC50 of 2.1 μM).

Figure 2.

Growth inhibition curves of N. fowleri KUL strain at different time points. Growth inhibition curves of trophozoites treated with pitavastatin at 4, 10, 16, and 24 h. Data points represent mean percentage growth inhibition and standard error of mean (SEM) of different concentrations of compounds.

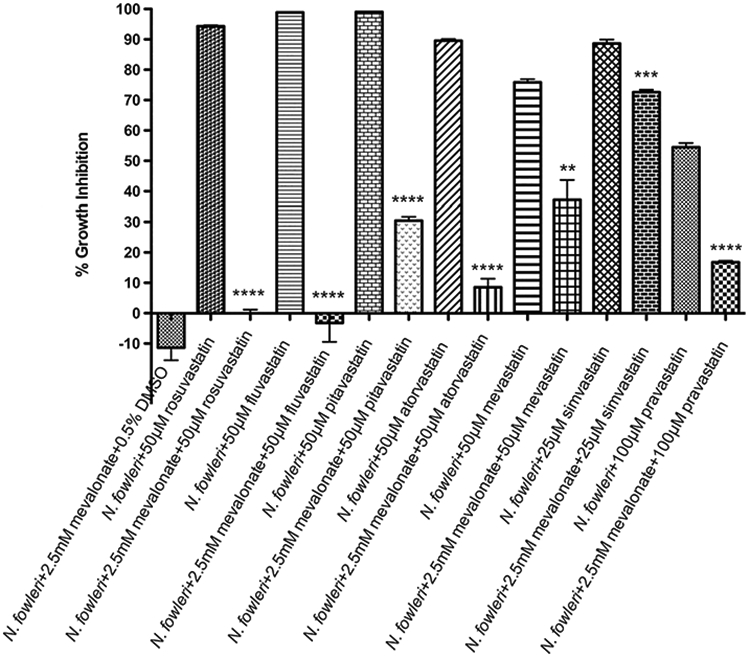

Effect of Mevalonate on Growth Inhibition by Statins.

To evaluate on-target activity of the HMGR inhibitors in N. fowleri, we hypothesized that pretreatment of N. fowleri with mevalonate, the product of HMGR, would offset inhibition induced by the statins. To assess whether mevalonate could rescue a deleterious phenotype induced by high concentration of statins, N. fowleri trophozoites were preincubated with 2.5 mM mevalonate for 24 h and then coincubated with 25 μM or 50 μM or 100 μM of investigated statins. While trophozoites treated with different statins but not preincubated with mevalonate exhibited about 55% to 99% growth inhibition, preincubation of parasite with mevalonate prior to the addition of statins prevented parasite death significantly (P < 0.005), confirming N. fowleri HMGR as the relevant target (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Rescue effect of mevalonate from growth inhibition by statins. N.fowleri trophozoites were coincubated with 2.5 mM mevalonate for 24 h prior to the addition of different concentrations of statins. Trophozoites were incubated for 48 h with respective statins and cell viability was measured by ATP-bioluminescence. Values plotted are the means and standard deviations of triplicate wells. *P < 0.05 by Student’s t test compared to statin-treated N. fowleri trophozoites.

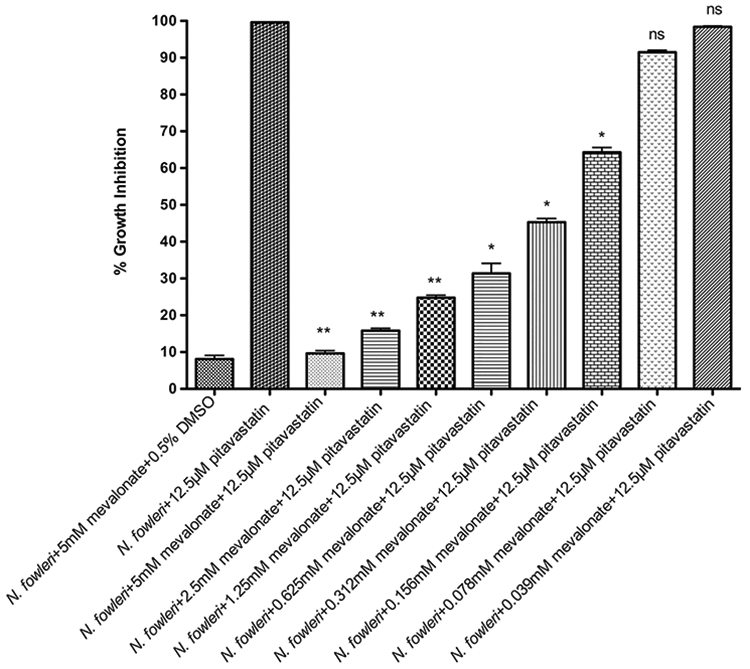

Effect of Different Concentrations of Mevalonate on Growth Inhibition by Pitavastatin.

Since N. fowleri can phagocytose host cells, it is possible that mevalonate produced by host cells can offset the effect of statins on N. fowleri. To determine the rescue effect of different concentrations of mevalonate, we preincubated N. fowleri trophozoites with different concentrations of mevalonate in triplicate in three independent experiments and then incubated the cells with 12.5 μM of pitavastatin. Cells incubated with 12.5 μM of pitavastatin alone produced 100% growth inhibition. While higher concentrations of mevalonate (0.156 mM to 5 mM) rescued the cells significantly (P < 0.05) from the effect of statin, 78 and 39 μM of mevalonate did not have significant effect (P = 0.07 and 0.16, respectively) on the rescue from the growth inhibitory effect of 12.5 μM of pitavastatin (Figure 4). This concentration of mevalonate (78 μM) is almost 2000 fold higher than the concentration of mevalonate present in human plasma (40 nM),16 suggesting that the human mevalonate may not rescue the parasite from the effect of a statin.

Figure 4.

Dose-dependent rescue effect of mevalonate from growth inhibition by pitavastatin. N. fowleri trophozoites were coincubated with different concentrations of mevalonate for 24 h prior to the addition of 12.5 μM of pitavastatin. Trophozoites were incubated for 48 h with statin, and cell viability was measured by ATP-bioluminescence. Values plotted are the means and standard deviations of triplicate wells. *P < 0.05 by Student’s t test compared with 12.5 μM of pitavastatin-treated N. fowleri trophozoites. ns = not significant, where P > 0.05 by Student’s t test compared to 12.5 μM of pitavastatin-treated N. fowleri trophozoites.

DISCUSSION

Given that adherence of amebae to host cells is critical in inducing infection,17 we reasoned that the sterol composition of the plasma membrane might play a central role in the pathogenesis of N.fowleri. We earlier showed that disruption of sterol biosynthesis with chemical inhibitors in N. fowleri is amebicidal and, thus, might be an effective therapeutic intervention strategy against highly fatal PAM.6,10 Among enzymes constituting the sterol biosynthetic pathway in eukaryotes, several have been studied over the years as targets for therapeutic agents to block sterol biosynthesis in humans and in pathogenic fungi.

The mevalonate pathway is essential in eukaryotes and is responsible for a diversity of fundamental biosynthetic activities leading to isoprenoids and sterols.18 HMGR is the rate-limiting enzyme in the pathway which catalyzes the conversion of HMG-CoA into mevalonate.19 HMGR inhibitors or statins prevent the conversion of HMG-CoA to l-mevalonate resulting in the inhibition of the downstream sterol biosynthesis and numerous isoprenoid metabolites such as geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate and farnesyl pyrophosphate.20 The genome of N. fowleri contains a gene encoding HMGR; the catalytic domains of human and N. fowleri HMGR share <60% sequence identity with only two amino acid substitutions in the active site of the enzyme. The similarity of human and amebae HMGR inspired us to test well-tolerated and widely used HMGR inhibitors or cholesterol-lowering statins against N. fowleri.

The reason for the paucity of small-molecule anti-PAM drugs is that the great majority of them do not cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The currently used anti-PAM drug deoxycholate amphotericin B cannot achieve measurable concentrations in CSF in the presence of normal and inflamed meninges,21 and deoxycholate amphotericin B provided only 50% protection of mice from PAM at a dose equivalent to that used in humans.22 Another drug of choice, miltefosine, has unknown brain permeability.23 Low-level CSF accumulation of miltefosine was found in a patient infected with another free-living ameba Balamuthia mandrillaris, but brain tissue penetration was not evaluated directly in this patient.24 Statins are able to penetrate the BBB,25,26 and several studies have shown that the BBB permeability of statins depends on their lipophilic or hydrophilic characters.27,28 Evidence indicate that statins provide neuroprotection in both Alzheimer disease and non-Alzheimer disease mouse models.29,30

Our study demonstrated the potent inhibitory effects of pitavastatin and fluvastatin against N. fowleri. The identification of fluvastatin as an amebicidal statin is consistent with an earlier finding,31 but fluvastatin is not BBB permeable32,33 and was not equally effective against multiple strains of different genotypes. Pitavastatin, on the other hand, is BBB permeable,34 equipotent to amphotericin B and 180-fold more potent than miltefosine against KUL strain. It was equally effective against Australian and U.S. strains and maintained a low micromolar EC50.

Pitavastatin (LIVALO) has the unique cyclopropyl group that influences its binding to HMGR and protects from metabolism by CYP450.35 Pitavastatin exhibited a BBB penetration of 10–15% in an in vitro study.34 It has more favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles and has fewer drug-drug interactions than other available statins. Unlike other statins, pitavastatin is not affected by food and it has >60% absolute bioavailability with 80% oral absorption.36 The current FDA-recommended maximum dose of pitavastatin is 4 mg. In a Phase I study, following a single oral dose of 4 mg pitavastatin calcium, mean plasma Cmax of pitavastatin was found 232.91 ng/mL or 0.55 μM,37 which is about 2-fold higher than the in vitro EC50 of pitavastatin against the European strain. In a recent Phase I clinical trial with an intravenous formulation of pitavastatin, mean plasma Cmax of pitavastatin reached 366.8 ng/mL or 0.87 μM after a single dose of 8 mg.38

Pitavastatin is rapidly absorbed after oral administration and reaches peak plasma concentrations in humans within 1 h. The elimination half-life of pitavastatin is approximately 12 h.35 Our in vitro study demonstrated that pitavastatin is relatively fast-acting and 81% growth inhibition of trophozoites was achieved within 16 h postexposure. This rapid action of pitavastatin is not only important for the drug with half-life of 12 h but also for a rapidly progressive infection like PAM.

To validate HMGR as a drug target, we have confirmed the on-target activity of statins by rescuing N. fowleri from lethal effects of statins by pretreatment of N. fowleri with mevalonate, the product of HMGR. We demonstrated that the N. fowleri HMGR was selectively targeted by statins. While high concentrations of mevalonate restored the cells from the inhibitory effect of statin, a concentration of mevalonate that is almost 2000 fold higher than the physiological concentration of mevalonate present in human plasma16 could not rescue the ameba from the lethal effect of pitavastatin. Although in vivo studies from rats showed that plasma mevalonate represents an actively circulating pool of mevalonate, synthesis of mevalonate in rat brain was found negligible.39 This suggests that the host mevalonate, especially the mevalonate in the brain, may not alleviate the amebicidal effect of a statin.

Pitavastatin is not metabolized by CYP3A4 and undergoes minimal first-pass metabolism, and therefore, it has low drug–drug interactions potential.40 According to LIVALO (pitavastatin) label, the most frequent adverse reactions associated with oral pitavastatin are myalgia, back pain, diarrhea, constipation, and pain in the extremity. The intravenous formulation used in a Phase I clinical trial did not show any undesirable adverse effects.38 Relatively short treatment regimens required for PAM should minimize possible side effects reported for pitavastatin. Another advantage of pitavastatin is that it was found to be well tolerated in children,41,42 and recently, it received FDA approval for use in pediatric patients of 8–16 years old.

Future studies will investigate the impact of pitavastatin on the cell ultrastructure of N. fowleri and will require validation of the efficacy of pitavastatin in an animal model of PAM. Although pitavastatin is considered BBB-permeable, future experiments with our animal model of PAM43 can confirm the presence of the drug in the brain of infected animals. In vivo proof of efficacy of pitavastatin will make it suitable for “off label” use in the treatment of PAM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

N. fowleri Culture.

N. fowleri reference European strain KUL was acquired from American Type Culture Collection (#30808). To maintain high virulence, mice were periodically infected with KUL trophozoites, and brain tissues were harvested to recover the parasites. Recovered highly virulent KUL trophozoites were used in the experiments. U.S. clinical strains Davis, CAMP, and TY belonging to genotypes I, II, and III, respectively, and Australian strain CDC:V1005 were acquired from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States. The trophozoites were axenically maintained in Nelson’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C.6 All experiments were performed using trophozoites harvested at 48 h when they were at the logarithmic phase of growth.

Homology Modeling of HMGR of N. fowleri.

Sequences of N. fowleri and human HMGR were obtained from AmoebaDB and UniProt; accession numbers NF0036310 and P04035, respectively. Sequence alignment was generated using ICM-Pro using the zero end-gap global alignment method,44 and ESPript 3.0 was used to render the alignment figure.45 The comparison matrix was introduced by Gonnet et al.46 A residue conservation profile was generated to show the amino acids essential for the structure and function of the protein. The amino acid counts were normalized by the same factor in all alignment positions. The crystal structure of the human HMGR catalytic domain bound to atorvastatin (PDB ID: 1HWK) was used as a template. Based on the alignment and structure template, the homology model of HMGR of N. fowleri was built with the default parameters in ICM-Pro, with all side chains and insertions/deletions sampled and refined via a biased probability Monte Carlo method.47 The pocket for atorvastatin was formed by two proteins (a homodimer), and each homodimer was homology-modeled.

In Vitro Activity of HMGR Inhibitors against N. fowleri.

Stocks of tested statins atorvastatin, mevastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin, rosuvastatin, fluvastatin, and pitavastatin were prepared as 10 mM in DMSO. Control standard of care drugs amphotericin B and miltefosine were prepared as 10 mM in DMSO and 40 mM in sterile water, respectively. Statins and amphotericin B were serially diluted in DMSO 8 or 16 times to prepare concentrations ranging from 10 mM to 0.078 mM or 10 mM to 0.0003 mM. Miltefosine was serially diluted in sterile water to generate concentrations spanning 40 mM to 0.3 mM. 0.5 μL of each drug from each concentration was transferred in triplicate to 96-well Greiner Bio-One Cellstar white, flat-bottom microplates. 0.5% DMSO was used as a vehicle control and 50 μM of amphotericin B as a positive control. N. fowleri trophozoites of different strains were counted using a hemocytometer, and 10 000 trophozoites in 99.5 μL of Nelson medium were added to each well. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. At the end of incubation, CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) was utilized to measure generation of ATP-bioluminescence.48 The luminescence was quantified using an EnVision 2104 Multilabel Reader (PerkinElmer). The data were analyzed on GraphPad Prism 6 to determine EC50 values and 95% confidence intervals.

Growth Inhibition as a Function of Time.

To determine the killing kinetics of pitavastatin, N. fowleri laboratory reference KUL strain trophozoites were incubated with pitavastatin in triplicate at serially diluted concentrations ranging from 50 μM to 0.0015 μM for 4, 10, 16, and 24 h at 37 °C. The growth inhibition at different time points was measured by CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay, and the EC50 values of pitavastatin at different time points were determined.

Effect of Mevalonate on Growth Inhibition by Statins.

To determine whether addition of mevalonate, the product of HMGR, could offset the deleterious effect induced by statins, 10 000 KUL trophozoites were preincubated with 2.5 mM mevalonate in triplicate in a 96-well plate for 24 h at 37 °C. After 24 h, 50 μM each of rosuvastatin, fluvastatin, pitavastatin, atorvastatin, and mevastatin; 25 μM of simvastatin; and 100 μM of pravastatin were added in the medium containing mevalonate-treated N. fowleri, and trophozoites were incubated at 37 °C for additional 48 h. Trophozoites treated with 2.5 mM mevalonate and 0.5% DMSO were negative controls, and trophozoites treated with 50 μM of amphotericin B were positive controls in the assay. Trophozoites treated with 50 μM each of rosuvastatin, fluvastatin, pitavastatin, atorvastatin, and mevastatin; 25 μM of simvastatin; and 100 μM of pravastatin were included as experimental controls. At the end of incubation, cell viability was determined by CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay.

Effect of Different Concentrations of Mevalonate on Growth Inhibition by Pitavastatin.

To determine the effect of different concentrations of mevalonate on pitavastatin-treated trophozoites, 10 000 N. fowleri KUL trophozoites were preincubated with mevalonate in triplicate at serially diluted concentrations ranging from 5 mM to 0.039 mM at 37 °C for 24 h. After 24 h, mevalonate-treated trophozoites in a 96-well plate were incubated with 12.5 μM of pitavastatin for additional 48 h. Trophozoites treated with 5 mM mevalonate and 0.5% DMSO were negative controls and trophozoites treated with 50 μM of amphotericin B were positive controls in the assay. Trophozoites treated with 12.5 μM pitavastatin were included as experimental controls. At the end of incubation, cell viability was determined by CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors are thankful to Dr. Conor Caffrey of UC San Diego for supplying statins for this work. This work was supported by the grants 1KL2TR001444, R21AI141210, R21AI133394, R21AI146460 from NIH to A.D., and grant R35GM131881 from NIH to R.A.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Hye Jee Hahn, Center for Discovery and Innovation in Parasitic Diseases, Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093-0756, United States.

Ruben Abagyan, Center for Discovery and Innovation in Parasitic Diseases, Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093-0756, United States.

Larissa M. Podust, Center for Discovery and Innovation in Parasitic Diseases, Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093-0756, United States

Shantanu Roy, Free-Living and Intestinal Amebas (FLIA) Laboratory, Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia, United States.

Ibne Karim M. Ali, Free-Living and Intestinal Amebas (FLIA) Laboratory, Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia, United States

Anjan Debnath, Center for Discovery and Innovation in Parasitic Diseases, Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093-0756, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Capewell LG, Harris AM, Yoder JS, Cope JR, Eddy BA , Roy SL, Visvesvara GS, Fox LM, and Beach MJ (2015) Diagnosis, Clinical Course, and Treatment of Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis in the United States, 1937–2013. J. Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 4 (4), e68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Jarolim KL, McCosh JK, Howard MJ, and John DT (2000) A light microscopy study of the migration of Naegleria fowleri from the nasal submucosa to the central nervous system during the early stage of primary amebic meningoencephalitis in mice. J. Parasitol 86 (1), 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Grace E, Asbill S, and Virga K (2015) Naegleria fowleri: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment options. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 59 (11), 6677–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Barnett ND, Kaplan AM, Hopkin RJ , Saubolle MA, and Rudinsky MF (1996) Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis with Naegleria fowleri: clinical review. Pediatr Neurol 15 (3), 230–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Linam WM, Ahmed M, Cope JR, Chu C, Visvesvara GS, da Silva AJ, Qvarnstrom Y, and Green J (2015) Successful treatment of an adolescent with Naegleria fowleri primary amebic meningoencephalitis. Pediatrics 135 (3), e744–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Debnath A, Calvet CM, Jennings G, Zhou W, Aksenov A, Luth MR, Abagyan R, Nes WD, McKerrow JH, and Podust LM (2017) CYP51 is an essential drug target for the treatment of primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis 11 (12), e0006104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Herbst R, Ott C, Jacobs T, Marti T, Marciano-Cabral F, and Leippe M (2002) Pore-forming polypeptides of the pathogenic protozoon Naegleria fowleri. J. Biol. Chem 277 (25), 22353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lee J, Kim JH, Sohn HJ, Yang HJ, Na BK, Chwae YJ, Park S, Kim K, and Shin HJ (2014) Novel cathepsin B and cathepsin B-like cysteine protease of Naegleria fowleri excretory-secretory proteins and their biochemical properties. Parasitol. Res 113 (8), 2765–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Shi D, Chahal KK, Oto P, Nothias LF, Debnath A, McKerrow JH, Podust LM, and Abagyan R (2019) Identification of Four Amoebicidal Nontoxic Compounds by a Molecular Docking Screen of Naegleria fowleri Sterol Delta8-Delta7-Isomerase and Phenotypic Assays. ACS Infect. Dis 5 (12), 2029–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zhou W, Debnath A, Jennings G, Hahn HJ, Vanderloop BH, Chaudhuri M, Nes WD, and Podust LM (2018) Enzymatic chokepoints and synergistic drug targets in the sterol biosynthesis pathway of Naegleria fowleri. PLoS Pathog. 14 (9), e1007245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zyserman I, Mondal D, Sarabia F, McKerrow JH, Roush WR, and Debnath A (2018) Identification of cysteine protease inhibitors as new drug leads against Naegleria fowleri. Exp. Parasitol 188, 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Duma RJ, and Finley R (1976) In vitro susceptibility of pathogenic Naegleria and Acanthamoeba speicies to a variety of therapeutic agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 10 (2), 370–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Chen LW, Lin CS, Tsai MC, Shih SF, Lim ZW, Chen SJ, Tsui PF, Ho LJ, Lai JH, and Liou JT (2019) Pitavastatin Exerts Potent Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects via the Suppression of AP-1 Signal Transduction in Human T Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci 20 (14), 3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Zhang X, Scialis RJ, Feng B, and Leach K (2013) Detection of statin cytotoxicity is increased in cells expressing the OATP1B1 transporter. Toxicol. Sci 134 (1), 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Escrig JI, Hahn HJ, and Debnath A (2020) Activity of Auranofin against Multiple Genotypes of Naegleria fowleri and Its Synergistic Effect with Amphotericin B In Vitro. ACS Chem. Neurosci 11 (16), 2464–2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Parker TS, McNamara DJ, Brown CD, Kolb R, Ahrens EH Jr., Alberts AW, Tobert J, Chen J, and De Schepper PJ (1984) Plasma mevalonate as a measure of cholesterol synthesis in man. J. Clin. Invest 74 (3), 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Martinez-Castillo M, Cardenas-Zuniga R, Coronado-Velazquez D, Debnath A, Serrano-Luna J, and Shibayama M (2016) Naegleria fowleri after 50 years: is it a neglected pathogen? J. Med. Microbiol 65 (9), 885–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Miziorko HM (2011) Enzymes of the mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 505 (2), 131–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Edwards PA, and Ericsson J (1999) Sterols and isoprenoids: signaling molecules derived from the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem 68, 157–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gazzerro P, Proto MC, Gangemi G, Malfitano AM, Ciaglia E, Pisanti S, Santoro A, Laezza C, and Bifulco M (2012) Pharmacological actions of statins: a critical appraisal in the management of cancer. Pharmacol. Rev 64 (1), 102–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Groll AH, Piscitelli SC, and Walsh TJ (1998) Clinical pharmacology of systemic antifungal agents: a comprehensive review of agents in clinical use, current investigational compounds, and putative targets for antifungal drug development. Adv. Pharmacol 44, 343–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Goswick SM, and Brenner GM (2003) Activities of azithromycin and amphotericin B against Naegleria fowleri in vitro and in a mouse model of primary amebic meningoencephalitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 47 (2), 524–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Dorlo TP, Balasegaram M, Beijnen JH, and de Vries PJ (2012) Miltefosine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of leishmaniasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 67 (11), 2576–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Roy SL, Atkins JT, Gennuso R, Kofos D, Sriram RR, Dorlo TP, Hayes T, Qvarnstrom Y, Kucerova Z, Guglielmo BJ, and Visvesvara GS (2015) Assessment of blood-brain barrier penetration of miltefosine used to treat a fatal case of granulomatous amebic encephalitis possibly caused by an unusual Balamuthia mandrillaris strain. Parasitol. Res 114 (12), 4431–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cibickova L (2011) Statins and their influence on brain cholesterol. J. Clin. Lipidol 5 (5), 373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Schachter M (2005) Chemical, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of statins: an update. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol 19 (1), 117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Johnson-Anuna LN, Eckert GP, Keller JH, Igbavboa U, Franke C, Fechner T, Schubert-Zsilavecz M, Karas M, Muller WE, and Wood WG (2005) Chronic administration of statins alters multiple gene expression patterns in mouse cerebral cortex. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 312 (2), 786–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Saheki A, Terasaki T, Tamai I, and Tsuji A (1994) In vivo and in vitro blood-brain barrier transport of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors. Pharm. Res 11 (2), 305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Li L, Cao D, Kim H, Lester R, and Fukuchi K (2006) Simvastatin enhances learning and memory independent of amyloid load in mice. Ann. Neurol 60 (6), 729–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Piermartiri TC, Figueiredo CP, Rial D, Duarte FS, Bezerra SC, Mancini G, de Bem AF, Prediger RD, and Tasca CI (2010) Atorvastatin prevents hippocampal cell death, neuroinflammation and oxidative stress following amyloid-beta(1–40) administration in mice: evidence for dissociation between cognitive deficits and neuronal damage. Exp. Neurol 226 (2), 274–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Rizo-Liendo A, Sifaoui I, Reyes-Batlle M, Chiboub O, Rodriguez-Exposito RL, Bethencourt-Estrella CJ, San Nicolas-Hernandez D, Hendiger EB, Lopez-Arencibia A, Rocha-Cabrera P, Pinero JE, and Lorenzo-Morales J (2019) In Vitro Activity of Statins against Naegleria fowleri. Pathogens 8 (3), 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Guillot F, Misslin P, and Lemaire M (1993) Comparison of fluvastatin and lovastatin blood-brain barrier transfer using in vitro and in vivo methods. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol 21 (2), 339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Shepardson NE, Shankar GM, and Selkoe DJ (2011) Cholesterol level and statin use in Alzheimer disease: II. Review of human trials and recommendations. Arch. Neurol 68 (11), 1385–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Sierra S, Ramos MC, Molina P, Esteo C, Vazquez JA, and Burgos JS (2011) Statins as neuroprotectants: a comparative in vitro study of lipophilicity, blood-brain-barrier penetration, lowering of brain cholesterol, and decrease of neuron cell death. J. Alzheimer's Dis 23 (2), 307–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hu M, and Tomlinson B (2014) Evaluation of the pharmacokinetics and drug interactions of the two recently developed statins, rosuvastatin and pitavastatin. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol 10 (1), 51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Catapano AL (2010) Pitavastatin - pharmacological profile from early phase studies. Atheroscler. Suppl. 11 (3), 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Luo Z, Zhang Y, Gu J, Feng P, and Wang Y (2015) Pharmacokinetic Properties of Single- and Multiple-Dose Pitavastatin Calcium Tablets in Healthy Chinese Volunteers. Curr. Ther. Res 77, 52–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Nakano K, Matoba T, Koga JI, Kashihara Y, Fukae M, Ieiri I, Shiramoto M, Irie S, Kishimoto J, Todaka K, and Egashira K (2018) Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of NK-104-NP. Int. Heart J 59 (5), 1015–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Hellstrom KH, Siperstein MD, Bricker LA, and Luby LJ (1973) Studies of the in vivo metabolism of mevalonic acid in the normal rat. J. Clin. Invest 52 (6), 1303–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Catapano AL (2012) Statin-induced myotoxicity: pharmacokinetic differences among statins and the risk of rhabdomyolysis, with particular reference to pitavastatin. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol 10 (2), 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Braamskamp MJ, Stefanutti C, Langslet G, Drogari E, Wiegman A, Hounslow N, Kastelein JJ, and on behalf of the PASCAL Study Group (2015) Efficacy and Safety of Pitavastatin in Children and Adolescents at High Future Cardiovascular Risk. J. Pediatr 167 (2), 338–343.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Harada-Shiba M, Kastelein JJP, Hovingh GK, Ray KK, Ohtake A, Arisaka O, Ohta T, Okada T, Suganami H, and Wiegman A (2018) Efficacy and Safety of Pitavastatin in Children and Adolescents with Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Japan and Europe. J. Atheroscler. Thromb 25 (5), 422–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Debnath A, Tunac JB, Galindo-Gomez S, Silva-Olivares A, Shibayama M, and McKerrow JH (2012) Corifungin, a new drug lead against Naegleria, identified from a high-throughput screen. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 56 (11), 5450–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Shi D, Svetlov D, Abagyan R, and Artsimovitch I (2017) Flipping states: a few key residues decide the winning conformation of the only universally conserved transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (15), 8835–8843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Robert X, and Gouet P (2014) Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Gonnet GH, Cohen MA, and Benner SA (1992) Exhaustive matching of the entire protein sequence database. Science 256 (5062), 1443–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Abagyan R, and Totrov M (1994) Biased probability Monte Carlo conformational searches and electrostatic calculations for peptides and proteins. J. Mol. Biol 235 (3), 983–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Debnath A, Nelson AT, Silva-Olivares A, Shibayama M, Siegel D, and McKerrow JH (2018) In Vitro Efficacy of Ebselen and BAY 11–7082 Against Naegleria fowleri. Front. Microbiol 9, 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]