Abstract

Bilateral hearing loss is attributed to almost 50% of times with genetic etiology, while most unilateral sensorineural hearing loss (USNHL) are not attributable to it. Limited literature is available on epidemiology of USNHL. Etiology of USNHL is very diverse and vast, it ranges from as common as Meniere’s disease to as rare as an electric shock injury. A prospective study was carried out to find rare causes of USNHL in adults. In this manuscript, we present a case series of 7 rare etiologies of USNHL in adults like auditory neuropathy, chemoradiotherapy, dialysis-induced SNHL, common cavity inner ear malformation, multiple sclerosis, acute otitis media-induced SNHL and vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. This study discusses the rare possible etiologies of USNHL that can be easily missed if these are not ruled out properly. We present these cases to consider these heterogeneous and distinct causes of USNHL because of rarity of these etiologies. If such an etiology is diagnosed in time, they may be managed effectively.

Keywords: Sensorineural hearing loss, Multiple sclerosis, Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia, Renal failure

Introduction

In unilateral sensorineural hearing loss (USNHL), SNHL (air conduction threshold of > 25 dB with an air–bone gap of less than 10 dB) is present only in one ear with the other ear being completely normal. USNHL has been found to affect 7.9–13.3% of the Indian population [1]. The common causes of USHNL includes Idiopathic Sudden SNHL, trauma, acoustic neuroma, Meniere’s disease, Mumps, trauma, infections, noise, etc. [2]. A proper workup of patients with USNHL includes detailed history, examination, various audiological, radiological and laboratory tests. Contrast enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CEMRI) and Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) remain the two of the most prudent investigation to rule out retrocochlear pathology. Identification of the etiology is the first step for providing an appropriate treatment. Hence, this manuscript presents seven rare causes of USNHL in adults which can be easily missed out during workup of such patients.

Material and Methods

A prospective study was carried out with 130 adult patients of USNHL in department of ENT from January 2018 to June 2019. Out of these 130 cases, we identified 7 rare cases of USHNL.

Cases

Case 1

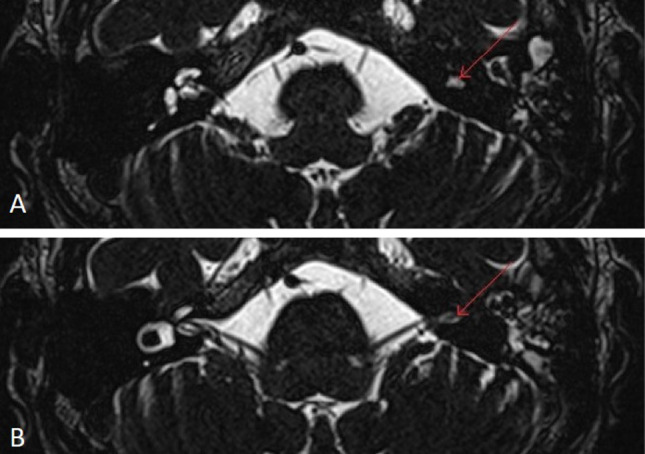

A 40-year-old male presented with complaints of left ear decreased hearing since childhood. He had no other complaints or co-morbidity. On examination, tympanic membrane was normal. On audiological workup, he was found to have left sided profound hearing loss (Fig. 1), absent ipsilateral reflexes and absent Otoacoustic Emissions (OAE). ABR was not done as it was a profound hearing loss. On CEMRI temporal bone, the patient was found to have a single ovoid chamber representing cochlea and vestibule with its neural structures entering into its centre through the internal auditory canal. (Fig. 2) A diagnosis of left common cavity Inner Ear Malformation (IEM) was made, using Sennaroglu and Bajin classification system. Patient was advised hearing aid and otoprotective measures as he could not afford cochlear implantation.

Fig. 1.

Showing pure tone audiogram of patient with profound SNHL in left ear

Fig. 2.

Showing axial T2 weighted MRI of temporal bone, a single ovoid chamber representing both cochlea and vestibule on left (common cavity inner ear malformation), marked red arrow, b common cavity with neural connection at its centre through internal auditory canal, markd red arrow

Case 2

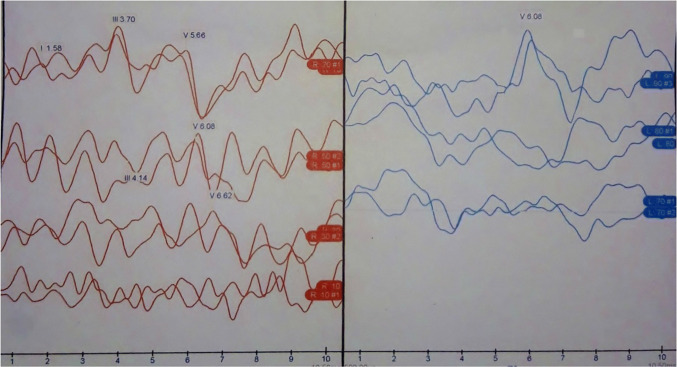

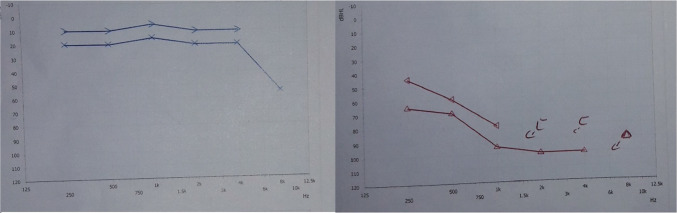

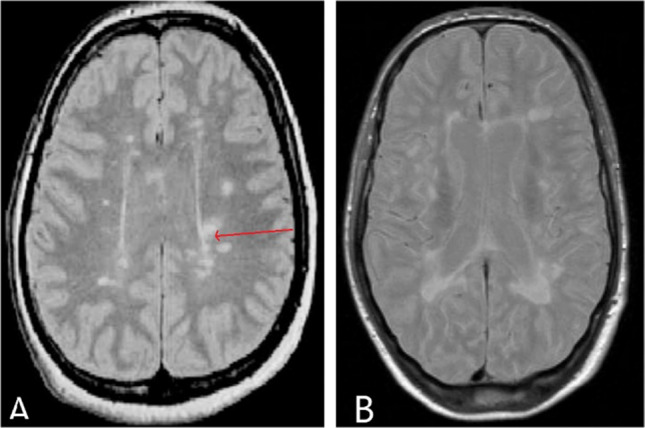

A 37-year-old male presented with left ear ringing, left ear decreased hearing, vertigo and left eye decreased vision for 1 year. Patient had a past history of the left eye decreased vision 1 ½ year back which recovered fully after some time. On examination, tympanic membrane was normal on both sides and he had normal clinical tests of vestibular examination. On audiological workup, he was found to have moderate-severe SNHL hearing loss and absent ipsilateral reflex in impedance audiometry. There was absent wave I and III and increased interaural latency for wave V [6.06 ms, Normal = 5.6–5.8 ms, and after adding correction factor for this patient it is 5.7–5.9 ms) in ABR. (Fig. 3) On radiology, patient was found to have ill-defined T2/FLAIR hyperintensities in the periventricular, parasagittal, subcortical and deep white matter of bilateral cerebral hemispheres with Dawson fingers. (Fig. 4) Thus a diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) was made. Patient was referred to the neurology department for further treatment.

Fig. 3.

Showing moderate severe SNHL on left side with absent wave I and III and increased interaural latency for wave V in ABR

Fig. 4.

Showing MRI brain images, a T2-weighted image of multiple hyperintense lesions, suggestive of multifocal white matter pathology with dawson finger (marked red arrow), b T1-weighted images showing multiple hyperintense lesions with a predominant involvement of the periventricular regions

Case 3

A 46-year-old-male was referred from the department of Medicine with complaints of the sudden onset right ear decreased hearing and ringing for 5 days. Patient was a diagnosed case of chronic kidney disease with hypertension, diabetes and hyperparathyroidism. Patient developed these symptoms soon after patient underwent haemodialysis. Before dialysis patient’s serum creatinine was 7.53 mg/dl. On examination, he had normal otoscopic findings. On audiological workup, he was found to have severe SNHL, absent ipsilateral reflexes and absent OAE. (Fig. 5) CEMRI temporal bone was done which was normal. Patient was diagnosed as a case of Dialysis induced unilateral sudden SNHL.

Fig. 5.

Showing pure tone audiogram of patient with profound SNHL in right ear

Case 4

A 45-year-old female presented with complaints of progressive right ear decreased hearing and ringing for 1 month, following palliative radiotherapy with 2 cycles of concurrent chemotherapy for CNS metastasis (diagnosed on whole body Positron Emission Tomography scan) secondary to breast carcinoma (stage IV). On examination, he had normal otoscopic findings. On audiological workup, she was found to have profound hearing loss, absent ipsilateral reflexes and absent OAE. (Fig. 6) CEMRI temporal bone was done for the inner ear which was normal. Patient was diagnosed as a case of unilateral progressive SNHL secondary to chemoradiation.

Fig. 6.

Showing pure tone audiogram of patient with profound SNHL in right ear

Case 5

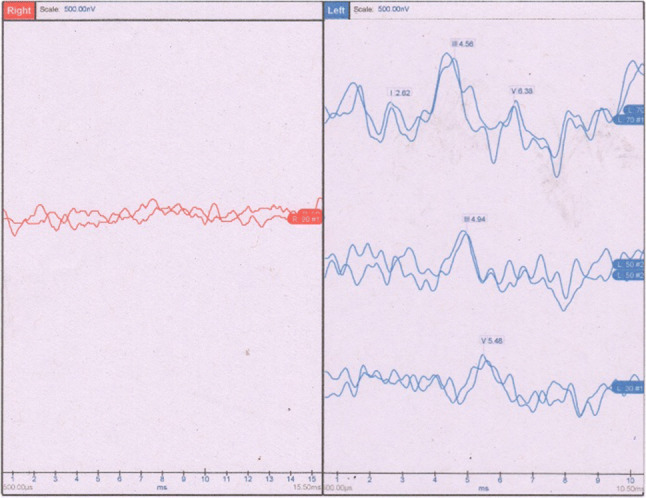

A 25-year-old male presented with an insidious onset right ear decreased hearing and ringing for 6 months. Patient had no other co-morbidities. On examination, he had normal otoscopic findings. On audiological workup, he was found to have mild SNHL, absent ipsilateral reflexes and present otoacoustic emissions and the speech discrimination score of 40%. There were absent neural response on right side in ABR. (Fig. 7) CEMRI temporal bone was done which was completely normal. Thus a diagnosis of unilateral auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder was made. Patient was advised hearing aid.

Fig. 7.

Showing auditory brainstem response of patient with absent neural responses in right ear

Case 6

A 16-year-old female presented with complaints of left earache and decreased hearing for 7 days. Patient had no other co-morbidities. On examination, she had a dull, intact tympanic membrane with the shadow of air bubbles in left ear. On audiological workup, she was found to have left moderate SNHL at speech frequencies and mixed at low frequencies (Fig. 8a), B type tympanogram with absent ipsilateral reflexes, absent otoacoustic emissions and the speech discrimination score of 100%. A diagnosis of acute otitis media induced SNHL was made. Patient was treated with oral antibiotics, decongestants and antihistaminic for 7 days. The patient’s hearing recovered to normal level after 2 weeks. (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Showing pure tone audiogram, a pre-treatment—left moderate SNHL at speech frequency with mixed at low frequency, b post-treatment—normal hearing sensitivity with mixed at low frequency

Case 7

A 19-year-old male presented with complaints of progressive right ear decreased hearing for 6 months with ringing. Patient had no other co-morbidities. On examination, he had a normal tympanic membrane. On audiological workup, he was found to have profound hearing loss with absent ipsilateral reflexes and absent otoacoustic emissions on affected ear. On CEMRI brain and temporal bone, patient was found to have tortuous basilar artery indenting over pontomedullary junction. A suspicion of vertebrobasilar artery dolichoectasia was made. (Fig. 9) Diagnosis was confirmed with MR angiography using smoker’s criteria. Patient was referred to neurosurgery department. Patient did not consent for any surgical intervention.

Fig. 9.

Showing MRI of patient, a T2 weighted 3-D space sequence that shows the right vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia contacting and indenting (marked star) the vestibulocochlear nerve at internal acoustic meatus (marked red arrow), b Axial T1-weighted post contrast image of dilated and elongated right vertebrobasilar artery crossing nerve at internal auditory meatus (marked red arrow) and indenting (marked star)

Discussion

USNHL is defined as an average pure tone hearing threshold of > 25 dB in air conduction (at 0.5, 1, 2, 4 kHz) of the affected ear with an air–bone gap of < 10 dB and a normal hearing in the other ear (< 15 dB) [3, 4]. The incidence of USNHL varies in different studies and ranges from 3.24–19.3% [1, 5]. The incidence of various aetiologies of USNHL also varies. Other than common risk factors that may add to the development of USNHL like noise exposure (most common), haemodialysis and radiation. Chronic kidney disease is also considered as a risk factor for the development of SNHL in patients [6, 7].

In literature, there is a diverse list of rare causes of USNHL like small patent foramen ovale with aneurysmal interatrial septum leading to a paradoxical thromboembolism causing sudden SNHL, sudden USNHL due to cerebral sinus venous thrombosis, spinal or general anaesthesia, pontine lesion causing CNS dysfunction as USNHL, a low voltage electric shock causing USNHL and facial palsy, Cogan syndrome, vasculitis, systemic sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease and other rheumatological disorders, sympathetic hearing loss and cochlear otosclerosis [8–19]. We present here 7 cases of USNHL due to auditory neuropathy, chemoradiotherapy, dialysis Induced sudden SNHL, malformation of inner ear, multiple sclerosis, acute otitis media-Induced SNHL and vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia.

Inner ear malformation comprises 66.7% of congenital hearing loss [20]. These can range from semicircular canal dilatation to complete labyrinthine aplasia [21]. SNHL is generally seen in association with these malformations, but till now no correlation has been established between the severity of the malformation and the patient’s hearing deficit. The lateral semi-circular canal is the most frequently affected canal by aplasia since it is the last canal to be formed [21]. Malformations of inner ear are classified based on the differences observed in cochlea into eight different groups by Levent Sennaroglu and Munir Demir Bajin in 2017 [22]. This classification system not only uses tha anatomical landmarks just to classify inner ear anomalies but also plays a major role in deciding the management of patients’ condition. Common cavity malformation comprises 7.3% cases of inner ear malformation in pediatric USNHL [20]. It is seen that these malformations are more common in USNHL than bilateral SNHL in pediatric population [20]. Our case 1 also presented with unilateral hearing loss since childhood. In an article by Muzzi E et al., they recommended early CT scan in such patients. Since, these patients have increased risk of developing recurrent bacterial meningitis due to CSF leak from IEM, more often from incomplete partition type 1 and common cavity malformations [23]. Hence in era of Universal hearing screening, every patient with SNHL and history of recurrent meningitis, should undergo early CT scan to rule out IEM and prevent sequela and mortality from it [23].

Multiple sclerosis (MS) can be seen in association with both sudden and insidious onset SNHL. It is well known that the incidence of sudden SNHL among patients with MS is 2–12 times higher than the normal. Presentation can be sudden onset (69%, equally affecting all frequencies, early stage) or progressive (31%, high frequency loss, late stage) bilateral SNHL in the majority [24, 25]. The most common cranial nerve involvement in MS is optic nerve, hence optic neuritis is initial symptom in 20% of patients [26]. OAEs are absent in 34% and ABR are altered in almost all MS patients, meaning damage may be cochlear or retrocochlear [24, 25]. ABR findings are generally increased absolute latency of all waveforms except I with or without increased interpeak latencies of I–III or III–V wave, as seen in our case with increased absolute latency of wave V [27, 28] Generally MRI fails to show signs of 8th nerve demyelination because changes in this nerve fall below the resolution level of today’s available MRI machines [24, 26, 29]. Dawson fingers (periventricular demyelinating plaques) are characteristic sign seen in MRI of patients with MS, as present in our case also. To detect active lesions in these patients, MRI needs to be done within 1–2 months of the onset of symptom [26]. Vestibular evoked myogenic potential has a better diagnostic accuracy than MRI for diagnosing MS [26]. Difficulty in finding lesions along the auditory pathway can be explained by involvement of a more central parts of the auditory tract [27, 28]. Despite the primary site of involvement in post-mortem examination of these patients, it is found in brainstem, its attribution in causing hearing loss still remains uncertain [27, 29].

Renal failure contributes to SNHL via osmotic alteration caused by haemodialysis, similarities between antigens of labyrinth and kidney, uremic neuropathy or ototoxins [6, 30]. Hearing loss is more commonly seen in higher frequencies in patients with renal disease, as seen in our case 3. Probability of hearing loss to occur and its severity increases with duration of renal failure and number of haemodialysis, as our case had underwent 11 times haemodialysis. Chronic dialysis results in building up of amyloid material with aluminium toxicity in inner ear, playing a role in hearing loss. Despite various studies, the exact cause for sudden SNHL in patients undergoing dialysis remains unknown [6].

Radiation-induced SNHL has been a well-recognized adverse effect that generally develops 6 to 24 months after radiation treatment and may progress to complete deafness [7]. However unilateral cases of hearing loss are rarely observed. Etiology of radiation induced SNHL can be vascular insufficiency, damage to cochlea and the cochlear nerve. Intensity modulated radiotherapy delivers higher doses to the cochlea and cause more damage, if the cochlea is not intentionally avoided, than conventional radiotherapy. Damage to cochlea was more pronounced if average delivered doses to cochlea was more than 50 Grays [7]. Chemotherapeutic agents are also known to cause SNHL which is usually bilateral. Since today we ought to prefer concurrent chemoradiation, it becomes difficult to correctly blame whether hearing loss is due to radiation or chemotherapy.

Auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) is described as a hearing disorder which mainly affects auditory nerve and inner hair cell function, in the presence of preserved outer hair cell activity in cochlea [31]. It presents bilaterally in most cases (incidence of unilateral ANSD is 7.3% of all ANSD), as ANSD was only seen in one ear in our case [31]. The site of lesion varies from inner hair cells to central pathways like olivocochlear tracts. The pathophysiology of ANSD involves abnormality of the inner hair cells or auditory nerve fibres in the form of demyelination or axonal loss. Presence of OAEs and absent acoustic reflexes suggest ANSD. There is absent neural response in ABR. However, ANSD with absent OAE can also be seen but there will be presence of cochlear microphonics. ANSD can be syndromic, nonsyndromic, congenital or acquired. In children with ANSD, even hearing aids may cause damage to cochlea thereby causing absent OAEs due to phonal trauma. Even residual fluid in the ear canal/middle ear or otitis media with effusion may cause the disappearance of OAEs [31]. Patients may benefit from speech processing type of hearing aid and cochlear implants, given the integrity of cochlear nerve is intact.

Otitis media-induced SNHL is believed to be due to the underlying inflammation of mucosa in the middle ear space. It mainly causes either the breakdown of the round window membrane, thereby allowing leakage of ions from the perilymph or increases its permeability to ions and toxins, causing ionic disequilibrium in the cochlea [32]. In a review article in 2017, there were 46 cases of acute otitis media associated SNHL out of which 75% had some recovery whereas 50% had complete recovery [33]. Most of these cases have favourable outcome with early treatment. Their management remains as simple as antibiotics, antihistaminic and decongestants with a very good outcome. Our patient also responded with favourable outcome.

Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia (VBD) is a rare arteriopathy and is subject to cause unilateral progressive SNHL associated with ipsilateral tinnitus [34]. It is also described as Cochlear vertebral entrapment syndrome by many in the literature. There have been various reports of SNHL caused by vascular sources such as aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, thrombosis and vascular loops [35, 36]. Macrovascular (visualized without the aid of a microscope) anomalies may arise from labyrinthine artery or proximal. VBD is diagnosed using Smoker’s criteria which include: 1) vertebrobasilar artery diameter > 4.5 mm; (2) length of basilar artery > 29.5 mm or length of the intracranial vertebral artery > 23.5 mm and (3) deviation of any point of the artery > 10 mm from its expected course [34]. Our case had length of basilar artery around 36 mm and intracranial vertebral artery 26 mm in MR angiography. Mechanical compression by such macrovascular structures is the only possible hypothesis available to explain such conditions [37, 38]. Microvascular decompression remains the treatment of choice for such cranial nerve vascular decompression syndromes [38].

Limited treatment options are available regarding USNHL. Partial resolution can be achieved through treatment. Other management options include hearing aids and cochlear implant. Further study needs to be done regarding understanding of rare causes of USNHL and its management protocol in adults.

Conclusion

USNHL should be evaluated for inner ear malformations so that early identification would prevent recurrent meningitis triggered by CSF leak in these patients. Multiple sclerosis is a medically treatable cause of USNHL which can be easily diagnosed using MRI. Multiple sclerosis and auditory neuropathy should be ruled out in a patient with hearing loss and altered vision. Dialysis induced SNHL is again a rare cause and patients should be informed about such events before undergoing procedure. Hearing loss might occur in long standing chronic kidney disease with multiple haemodialysis, more common in high frequencies. Early knowledge of chemoradiotherapy induced USNHL may give patient and his doctor an option to change the course or choice of treatment given to prevent further hearing loss. USNHL is a rare complication of acute otitis media. However, a careful clinical suspicion with minimal effort may provide a nearly 100% good outcome. Other rare cause like VBD should also be kept in differential diagnoses while evaluating USNHL. Macrovascular compression still remains the topic of controversy whether it causes SNHL or not. However, we need further studies with a large sample size to establish casualty of such associations.

Table 1.

Showing clinical characteristics of 7 rare cases of USNHL

| Features | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40 | 37 | 46 | 45 | 25 | 16 | 19 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male |

| Laterality | Left | Left | Right | Right | Right | Left | Right |

| Onset of hearing loss | – | Insidious | Sudden | Insidious | Insidious | Acute | Insidious |

| Progression of hearing loss | – | Progressive | Non-progressive | Progressive | Progressive | Non-progressive | Progressive |

| Duration of hearing loss | Childhood | 1 year | 5 days | 1 month | 6 months | 7 days | 6 months |

| Associated factor | – | Tinnitus + vertigo | Tinnitus | Tinnitus | – | Earache | Tinnitus |

| Severity | Profound | Moderate-severe | Severe | Profound | Mild | Moderate SNHL mixed at low frequency | Profound |

| Audiology of the affected ear |

B type, reflexes absent, OAE:absent |

Absent ipsilateral reflexes; absent wave I and III and increased interaural latency for wave V ABR | Absent ipsilateral reflexes and absent OAE | Absent ipsilateral reflexes and absent OAE | Absent ipsilateral reflexes and present OAE, speech discrimination score of 40% with the absent neural response in ABR | B type tympanogram with absent ipsilateral reflexes and absent OAEs and speech discrimination score of 100% | Absent ipsilateral reflexes and absent otoacoustic emissions on affected ear |

| MRI temporal bone | Single, ovoid chamber representing cochlea and vestibule with its neural structures entering into its centre through internal auditory canal | Ill-defined T2/FLAIR hyperintensities in the periventricular, parasagittal, subcortical and deep white matter of bilateral cerebral hemispheres with Dawson fingers | Normal | Normal | Normal | – | Tortuous vertebral and basilar artery with indentation over pontomedullary junction |

| Diagnosis | Common cavity inner ear malformation | Multiple sclerosis | Dialysis induced sudden SNHL | Chemoradiotherapy induced SNHL | Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder | Acute otitis media-induced SNHL | vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia |

Acknowledgements

The study has not received funding from any organization or institution and does not involve any potential conflict of interest (financial and non-financial). Procedures performed in the study was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Funding

Authors have not received any funding for this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amit Kumar Tyagi, Email: dramit4111@gmail.com.

Kartikesh Gupta, Email: kartikesh28@gmail.com.

Amit Kumar, Email: dramit4111@gmail.com.

Saurabh Varshney, Email: drsaurabh68@gmail.com.

Rachit Sood, Email: soodrachit@gmail.com.

Manu Malhotra, Email: manumalhotrallrm@gmail.com.

Madhu Priya, Email: drpriyamadhu@gmail.com.

Abhishek Bhardwaj, Email: abhi04stanley@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Bansal D, Varshney S, Malhotra M, Joshi P, Kumar N. Unilateral sensorineural hearing loss: a retrospective study. Indian J Otol. 2016;22:262–267. doi: 10.4103/0971-7749.192174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Usami S, Kitoh R, Moteki H, Nishio S, Kitano T, Kobayashi M, et al. Etiology of single-sided deafness and asymmetrical hearing loss. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 2017;137(sup565):S2–S7. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2017.1300321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deafness and hearing loss (2019) Available from: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-los. Accessed 2 Mar 2020

- 4.Taha MAM, Ahmed SAO, Abdulrahim MA. Associated factors of unilateral sensorineural hearing loss among sudanese patients. SM Otolaryngol. 2017;1(2):1006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamwal P, Kishore K, Sharma M, Goel M. Pattern of sensorineural hearing loss in patients attending ENT OPD. JK Sci. 2017;19(1):33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang S-M, Lim HW, Yu H. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss in dialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2018;40(1):170–174. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2018.1450760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petsuksiri J, Sermsree A, Thephamongkhol K, Keskool P, Thongyai K, Chansilpa Y, et al. Sensorineural hearing loss after concurrent chemoradiotherapy in nasopharyngeal cancer patients. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl. 2011;6:19–19. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park P, Toung JS, Smythe P, Telian SA, La Marca F. Unilateral sensorineural hearing loss after spine surgery: case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2006;66(4):415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murad NJ, Patel C, Turner CR. Unilateral sensorineural hearing loss after general anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2008;63(5):559–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karmody CS, Valdez TA, Desai U, Blevins NH. Sensorineural hearing loss in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009;30(3):166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun EM, Stanzenberger H, Nemetz U, Luxenberger W, Lackner A, Bachna-Rotter S, et al. Sudden unilateral hearing loss as first sign of cerebral sinus venous thrombosis? A 3-year retrospective analysis. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(4):657–661. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31828dae68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wieczorek SS, Anderson ME, Harris DA, Mikulec AA. Enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome mimicking otosclerosis in adults. Am J Otolaryngol. 2013;34(6):619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozkiris M. Unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and facial nerve paralysis associated with low-voltage electrical shock. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93(2):62–66. doi: 10.1177/014556131409300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciorba A, Corazzi V, Cerritelli L, Bianchini C, Scanelli G, Aimoni C. Patent foramen ovale as possible cause of sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a case report. Med Princ Pract Int J Kuwait Univ Health Sci Cent. 2017;26(5):491–494. doi: 10.1159/000484247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noureldine MHA, Kikano R, Riachi N, Ahdab R. Hyperacoustic hypoacusis: a new pontine syndrome-Case report. Brain Inj. 2017;31(10):1396–1397. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1317362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuan C-C, Kaga K, Tsuzuku T. Tuberculous meningitis-induced unilateral sensorineural hearing loss: a temporal bone study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127(5):553–557. doi: 10.1080/00016480600951418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan PF, Volsky PG, Strasnick B. Sympathetic hearing loss: A review of current understanding and report of 2 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 2016;95(4–5):166–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kariya S, Fukushima K, Kataoka Y, Tominaga S, Nishizaki K. Inner-ear obliteration in ulcerative colitis patients with sensorineural hearing loss. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(8):871–874. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107001351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okhovat S, Fox R, Magill J, Narula A. Sudden onset unilateral sensorineural hearing loss after rabies vaccination. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;15:2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-211977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masuda S, Usui S. Comparison of the prevalence and features of inner ear malformations in congenital unilateral and bilateral hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;125:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel G, Espitalier F, Delemazure A-S, Bordure P. Isolated lateral semicircular canal aplasia: Functional consequences. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2016;133(3):199–201. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sennaroğlu L, Bajin MD. Classification and Current Management of Inner Ear Malformations. Balkan Med J. 2017;34:397–411. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.2017.0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muzzi E, Gregori M, Orzan E. Inner Ear Malformations and Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss— the Elephant in the Room. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(9):874–875. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greco A, Stabile MR, Bernitsas E. Sudden hearing loss as an early detector of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:4611–4624. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201807_15520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ralli M, Stadio AD, Visconti IC, Russo FY, Orlando MP, Balla MP, et al. Otolaryngologic symptoms in multiple sclerosis: a review. Int Tinnitus J. 2018;22(2):160–169. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atula S, Sinkkonen S, Saat R, Sairanen T, Atula T. Association of multiple sclerosis and sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Mult Scler J - Exp Transl Clin. 2016;2:205521731665215. doi: 10.1177/2055217316652155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tekin M. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss in a multiple sclerosis case. North Clin Istanb. 2014;1(2):109. doi: 10.14744/nci.2014.35744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daugherty WT, Lederman RJ, Nodar RH. Hearing Loss in Multiple Sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1983;40:33–35. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1983.04050010053013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curé JK, Cromwell LD, Case JL, Johnson GD, Musiek FE. Auditory dysfunction caused by multiple sclerosis: detection with MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11(4):817–820. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peyvandi A, Roozbahany NA. Hearing loss in chronic renal failure patient undergoing hemodialysis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off Publ Assoc Otolaryngol India. 2013;65(Suppl 3):537–540. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0454-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Q-J, Lan L, Shi W, Wang D-Y, Qi Y, Zong L, et al. Unilateral auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 2012;132(1):72–79. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.629630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song JE, Sapthavee A, Cager GR, Saadia-Redleaf MI. Pseudo-sudden deafness. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121(2):96–99. doi: 10.1177/000348941212100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith A, Gutteridge I, Elliott D, Cronin M. Acute otitis media associated bilateral sudden hearing loss: case report and literature review. J Laryngol Otol. 2017;131(S2):S57–61. doi: 10.1017/S0022215117000779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilbow RC, Ruhl DS, Hashisaki GT. Unilateral sensorineural hearing loss associated with vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2018;39(1):e56–e57. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy TP. Macrovascular sensorineural hearing loss. Am J Otol. 1991;12(2):88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shim HJ, Song DK, Lee SW, Lee DY, Park JH, Shin JH, et al. A case of unilateral sensorineural hearing loss caused by a venous malformation of the internal auditory canal. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(9):1479–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu C-H, Lin S-K, Chang Y-J. Cochlear vertebral entrapment syndrome: a case report. Eur J Radiol. 2001;40:147–150. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(01)00393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yılmaz DM, Kişi ÖN, Erman T, İldan F. Unilateral sensorineural hearing loss associated with dolicoectasia of vertebral artery. Cukurova Med J Çukurova Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Derg. 2017;42(3):589–591. doi: 10.17826/cutf.324570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]