Abstract

Background

Differentiated thyroid cancer has been treated with radioiodine for almost 80 years, although controversial questions regarding radiation-related risks and the optimisation of treatment regimens remain unresolved. Multi-centre clinical studies are required to ensure recruitment of sufficient patients to achieve the statistical significance required to address these issues. Optimisation and standardisation of data acquisition and processing are necessary to ensure quantitative imaging and patient-specific dosimetry.

Material and methods

A European network of centres able to perform standardised quantitative imaging of radioiodine therapy of thyroid cancer patients was set-up within the EU consortium MEDIRAD. This network will support a concurrent series of clinical studies to determine accurately absorbed doses for thyroid cancer patients treated with radioiodine. Five SPECT(/CT) systems at four European centres were characterised with respect to their system volume sensitivity, recovery coefficients and dead time.

Results

System volume sensitivities of the Siemens Intevo systems (crystal thickness 3/8″) ranged from 62.1 to 73.5 cps/MBq. For a GE Discovery 670 (crystal thickness 5/8″) a system volume sensitivity of 92.2 cps/MBq was measured. Recovery coefficients measured on three Siemens Intevo systems show good agreement. For volumes larger than 10 ml, the maximum observed difference between recovery coefficients was found to be ± 0.02. Furthermore, dead-time coefficients measured on two Siemens Intevo systems agreed well with previously published dead-time values.

Conclusions

Results presented here provide additional support for the proposal to use global calibration parameters for cameras of the same make and model. This could potentially facilitate the extension of the imaging network for further dosimetry-based studies.

Keywords: Multi-centre trial, Dosimetry, Radioiodine, Differentiated thyroid cancer

Background

Radioiodine ([131I]NaI) has been used to treat thyroid cancer following partial or total thyroidectomy for nearly 80 years. Nevertheless, treatment regimens remain subject to controversy and administered activities can vary widely, in part due to a lack of evidence regarding potential risks from treatment. A consensus paper [1] developed by experts from the American Thyroid Association (ATA) [2], the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM), the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) and the European Thyroid Association (ETA) has established several principles regarding treatment and has highlighted areas in need of investigation. These ‘Martinique principles’ include the need to determine the optimal prescribed activity of radioiodine for adjuvant treatment and for patients at low risk. Furthermore, they recommend that major gaps in knowledge concerning the optimal use of radioiodine should be addressed by prospective studies.

A review by Hackshaw et al. [3] concluded that it is not possible to determine from the literature whether ablation success rates are higher with higher administered activities. Several authors have hypothesised that the ablation success rate is dependent on the absorbed dose delivered to residual thyroid tissue rather than on the activity administered [4–7]. A number of studies have shown that a large range of absorbed doses is observed in patients when empirical activities are used [4–12]. Previous studies that have investigated the relationship between the absorbed dose to the thyroid remnant and the treatment success rate have not been performed in a multi-centre setting, and treatment based on a dosimetry approach has, therefore, not been widely adopted. Multi-centre prospective clinical studies are ultimately necessary to resolve the controversies raised in the consensus paper [1] by the ATA, EANM, SNMMI and ETA.

Clinical studies performed in a multi-centre setting enable a wider input into the trial design and data analysis [13]. A summary of the physics aspects of setting up a multi-centre clinical trial involving imaging-based dosimetry has been provided in [14]. Multi-centre clinical studies involving a dosimetry component must be carefully planned and a consistent approach to quality assurance should be implemented to allow for the collation of results from the individual centres. Image data acquisition and processing can only be standardised to a certain level due to local differences in logistics, available equipment and constraints in ethics approvals and regulations.

Quantitative imaging is becoming more widely adopted [15] and will in future be part of many multi-centre clinical studies in nuclear medicine. Guidelines for quantitative imaging of 131I have been provided by the Committee on Medical Internal Radiation Dose (MIRD) in pamphlet 24 [16]. The EANM has issued guidelines on internal dosimetry for 131I[mIBG] treatment of neuroendocrine tumours [17].

Multi-centre studies with a dosimetry component require the set-up of a network of cameras able to perform quantitative imaging [14]. Zimmerman et al. [18] set up a multi-national, multi-centre phantom study to evaluate accuracy and reproducibility of SPECT image quantification with 133Ba as a surrogate for 131I. Wevrett et al. [19] assessed the feasibility of using an international inter-comparison exercise for 177Lu as a means to ensure consistency between clinical sites. A study in the Netherlands [20] reported on the variability in 177Lu SPECT quantification between different state-of-the-art SPECT/CT systems. Peters et al. [21] investigated the quantitative accuracy and inter-system variability of various SPECT/CT systems with phantom measurements using 99mTc in a multi-vendor and multi-centre setting. Dickson et al. [22] proposed a framework for DaTSCAN ([123I]FP-CIT) imaging standardisation. An example of a multi-centre clinical trial involving dosimetry for [123I]NaI and [131I]NaI is SEL-I-METRY [23], a phase II clinical trial using quantitative SPECT imaging to investigate the potential of selumetinib to resensitise advanced iodine refractory differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) to radioiodine. As part of SELIMETRY, a quantitative SPECT imaging network was set up in the UK [24].

MEDIRAD is a European Horizon 2020 funded project investigating the implications of medical low dose radiation exposure [25]. The overall objectives of MEDIRAD Work Package 3 (WP3) are to develop and implement the tools necessary to, for the first time in a multi-centre setting, investigate the range of absorbed doses delivered to healthy organs in patients undergoing thyroid ablation and to establish a threshold absorbed dose required for a successful ablation. Absorbed dose estimates to the thyroid remnant will be used to investigate the relationship between the radiation dose to the remnant tissue and treatment success. A sub-task of WP3 is to assess the variation between patient biokinetics, the success of ablation and the occurrence of short to mid-term toxicities. This is a concurrent series of non-randomised, non-blinded, prospective observational studies aiming to recruit 100 patients across four centres (Royal Marsden Hospital, Universitätsklinikum Marburg, Universitätsklinikum Würzburg and Institute Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse Oncopole). A series of SPECT/(CT) (hereafter referred to as SPECT(/CT)) and whole-body scans is performed following radioiodine therapy from 6 to 168 h post-administration to perform centralised dosimetry calculations for thyroid remnants, healthy organs and metastases. Whole-body (WB) retention measurements and, for a sub-group of patients, blood samples are collected to enable the calculation of WB and blood absorbed doses. Patients are followed up at regular clinical visits to assess the success of ablation and discover short to mid-term toxicity.

The aim of this work was to develop the required methodologies and perform the gamma camera performance assessments necessary for the set-up of a European imaging network for quantitative [131I]NaI imaging to support a concurrent series of dosimetry-based clinical studies for radioiodine therapy of thyroid cancer patients. A degree of flexibility was required to enable the set-up of these centres due to differences in local logistics and in the interpretation of radiation protection legislation in the four participating centres located in the three countries. Local radiation protection restrictions prevented the use of large amounts of liquid [131I]NaI to determine dead-time of the systems.

Methods

Setting up a network of gamma cameras for quantitative SPECT imaging

The four centres involved in the MEDIRAD study were equipped with a total of 5 SPECT(/CT) systems which are summarised in Table 1. All SPECT(/CT) systems were calibrated for quantitative high activity radioiodine imaging by performing pre-study site visits involving measurements to determine system volume sensitivity, recovery coefficients and dead-time characteristics for each SPECT(/CT) system used for the study.

Table 1.

Summary of the imaging systems used for the MEDIRAD clinical study

| System | Centre | Crystal thickness | Reconstruction software* | Attenuation correction** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siemens Symbia S | Centre A | 3/8″ | Flash 3D | Chang |

| Siemens Intevo (1) | Centre B | 3/8″ | Flash 3D | CT |

| Siemens Intevo (2) | Centre B | 3/8″ | Flash 3D | CT |

| Siemens Intevo Bold | Centre C | 3/8″ | Flash 3D | CT |

| GE Discovery 670 | Centre D | 5/8″ | Volumetrix MI | CT |

*Vendor-specific reconstruction software/algorithm

**Attenuation correction method used for present study

The system volume sensitivity characterises the system’s response to a uniform concentration of activity. SPECT recovery coefficients, defined as the ratio between the observed activity concentration in tomographic imaging and the true activity concentration [26], were determined to correct for partial volume and resolution effects on the activity concentration measured in the reconstructed SPECT images. Dead-time factors, defined as the ratio between the true count-rate and the observed count-rate of a detector, are used to correct the acquired image counts for counts lost due to detector paralysis when imaging high activities of 131I.

Prior to the site set-up measurements, it was ensured that each centre had performed the following routine quality control tests [27] according to local limits; photopeak position, 131I and/or 99mTc intrinsic uniformity, centre of rotation for high-energy collimators used in the study, SPECT/CT system alignment, extrinsic high-energy collimator flood, QC of weighing scales used in these measurements and QC of dose calibrators used in these measurements.

Activities used for the phantom measurements were measured with dose calibrators that were traceable to a national standard, had been calibrated using an accredited laboratory for calibration in the respective countries or was calibrated to a local standard (e.g. a calibrated high purity germanium detector).

Whole-body and SPECT acquisition and reconstruction protocols

Standardised SPECT acquisition and reconstruction protocols were used on all systems involved in the study for the site set-up measurements and all patient measurements. Triple-energy scatter correction was used on all systems. CT attenuation correction was performed using the local standard low-dose CT protocol. As no hybrid SPECT/CT system was available for one centre, the Chang attenuation correction [28] was applied for this centre. 131I acquisition and reconstruction parameters are summarised in Tables 2 and 3. All SPECT/CT reconstructions included resolution recovery.

Table 2.

Acquisition parameters used for 131I imaging as part of the MEDIRAD WP3 study

| Parameter | 131I acquisition protocol |

|---|---|

| Collimator | High Energy (HE) |

| Photopeak-energy window | 364 keV ± 10% |

| Lower scatter-energy window | 318 keV ± 3% |

| Higher scatter-energy window | 413 keV ± 3% |

| WB planar-acquisition mode | Continuous movement at 20 cm/min |

| SPECT(/CT) matrix | 128 × 128 |

| SPECT movement | Body contour |

| Projections | 2 × 30 (6° projection) |

| Time per projection | Adjusted based on measured count-rate for patient acquisition |

| CT | Standard low-dose protocol |

Table 3.

SPECT(/CT) reconstruction parameters used for 131I imaging as part of the MEDIRAD WP3 study

| Parameter | 131I reconstruction protocol |

|---|---|

| Reconstruction | OSEM (4 iterations, 10 subsets) |

| Attenuation correction (AC) | CTAC (one site: Chang with 0.11 cm−1 @ 364 keV) |

| Scatter correction | Triple-energy window (TEW) |

| Post-reconstruction filtering | None |

System volume sensitivity measurement

A cylindrical or body-shaped phantom with a volume greater than 6 l was used for all system volume sensitivity measurements based on local availability of phantoms. The volume of each phantom was accurately determined by measuring the weight of water needed to completely fill the phantom. In total, 40 ± 2 MBq of liquid [131I]NaI, 1 g of potassium iodine and 1 g of sodium thiosulphate were added to the phantom. The activity of 40 MBq was chosen to minimise the influence of dead-time of the SPECT systems on the measurements. The activity was measured accurately using a radionuclide calibrator. An acquisition of 100 kilo counts (kcounts) per SPECT projection was performed using the parameters in Table 2 and the image was reconstructed locally at each centre using the SPECT reconstruction parameters listed in Table 3.

The system volume sensitivity Qvol in counts-per-second per MBq (cps/MBq) was obtained from placing a 15 cm diameter volume-of-interest (VOI) in the centre of the reconstructed SPECT image of the phantom and was defined as:

| 1 |

where CVOI is the number of counts in the 15 cm VOI, is the activity concentration in the phantom decay corrected to the mid-point of the scan in MBq/ml, VVOI is the volume of the 15 cm VOI in ml, #P is the number of projections, and Ptime is the time per projection in seconds. The division of #P by a factor of 2 originates from the 2 detectors that were available for all SPECT(/CT) systems.

Uncertainty analysis was performed following recent EANM guidance [29]. Uncertainty in Qvol, u(Qvol), was estimated as:

| 2 |

CVOI, VVOI, #P, Ptime were assumed to have no associated measurement uncertainty. Uncertainty of , , was calculated as:

| 3 |

where Amid is the activity in MBq measured on the dose calibrator decay corrected to the mid-point of the scan and u(Amid) is the uncertainty in the dose calibrator measurement. u(Amid) was taken to be the measurement uncertainty provided on the calibration certificates for the respective calibrators or was assumed to be ± 5% where the measurement uncertainty was unknown. This is the acceptable calibration tolerance for field instruments in the UK [30]. Vphantom is the phantom volume in millilitre. The uncertainty in the phantom volume u(Vphantom) was estimated to be ± 5 ml due to the potential for small air bubbles in the filled phantom.

SPECT recovery coefficient determination

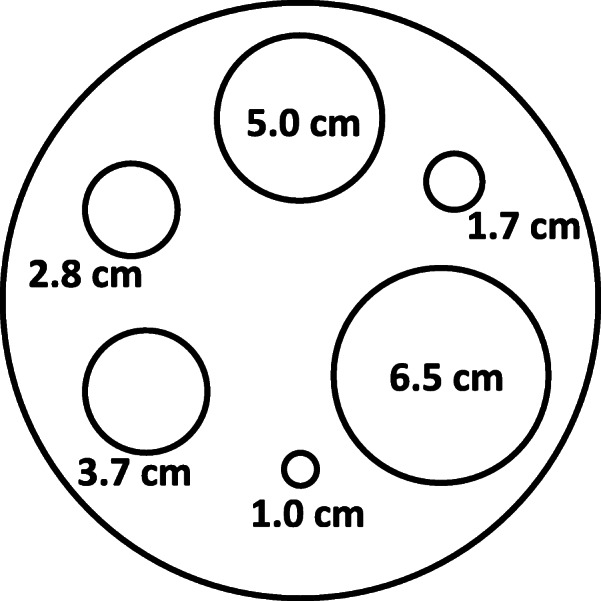

A cylindrical IEC head phantom (inner diameter 19.7 cm, inner height 18.3 cm) was used for the recovery coefficient measurements. A custom-designed lid with six 3D-printed sphere inserts was used with internal diameters of 1.0, 1.7, 2.8, 3.7, 5.0 and 6.5 cm (Fig. 1). Internal volumes of all spheres were obtained by measuring the weight difference of empty and filled spheres. The spheres were filled with a solution of water, [131I]NaI, potassium iodide and sodium thiosulphate. The 131I activity concentration in the spheres was specified to lie in the range of 0.5-0.6 MBq/ml at the time of acquisition. This is the expected maximum activity concentration in salivary glands estimated from published maximum uptake values by Liu et al. [31]. MEDIRAD is investigating the implications of medical low dose radiation exposure and the salivary glands are one of the organs-at-risk of particular interest in radioiodine therapy. The background compartment of the phantom was filled with water only. SPECT acquisitions of the phantom with 60 s per view and the parameters detailed in Table 2 were performed and reconstructed locally using the reconstruction parameters in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the placement of the six spheres used for the recovery coefficient determination in a cylindrical IEC head phantom

Spherical VOIs matching the nominal dimensions of the spheres were drawn on the CT. After interpolation of VOIs from CT to SPECT matrix size, the VOIs were copied to the reconstructed SPECT image. For the centre with no access to a hybrid SPECT/CT system, those VOIs were drawn on the reconstructed SPECT image. Recovery coefficients for each sphere were calculated as:

| 4 |

Here, Csphere is the number of counts in a sphere, is the activity concentration in the same sphere decay-corrected to the mid-point of the scan in MBq/ml, Vsphere is the volume of the sphere in millilitre, #P is the number of projections and Ptime is the time per projection in seconds. Qvol is the system volume sensitivity of the respective system. The division of #P by a factor of 2 originates from the 2 detectors that were available for all SPECT(/CT) systems.

Recovery coefficients for each sphere were plotted against sphere volume Vsphere and a recovery curve fitted using gnuplot version 5.2.7. The fitted recovery curve was defined as:

| 5 |

With V as the volume in millilitre, and β, γ and Rplateau are fit parameters. Parameter error estimates were obtained from gnuplot version 5.2.7 as the asymptotic standard errors.

To compare the recovery curves of different systems, the maximum observed absolute difference in the fitted recovery factor for a given volume was calculated as:

| 6 |

With Rc(V, System 1) and Rc(V, System 2) as the recovery factors of the two systems to be compared for a given volume V.

Dead-time characterisation

Dead-time measurements were performed using a 3700 MBq 131I capsule placed in a cylindrical scatter phantom made from polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) developed at the Royal Marsden Hospital (Sutton, UK). The phantom had a diameter of 13 cm and a height of 13 cm to represent a typical neck size, with a 2.5-cm-diameter hole in the middle extending from the top of the phantom to the centre for inserting the 131I capsule.

A series of static planar scans was acquired whilst the capsule was decaying. Measurements were performed approximately every second day until the capsule had decayed to 1 GBq and thereafter measurements were performed every 3-4 days. Each acquisition encompassed a static planar scan of 100 kcounts for each detector head with the capsule in the centre of the scatter phantom. Acquisition times per detector head were extracted from the DICOM headers to calculate the observed count rate. The phantom was placed on the patient bed at approximately 10 cm from the detector surface. Additionally, 10-min background acquisitions were performed with no source in place to correct for background activity.

Measurements with capsule activities below 100 MBq were assumed to be unaffected by dead-time and were used to determine the relationship between true count-rate and source activity level from a linear fit of background corrected count rates versus source activities.

Dead-time correction factors for each measurement were determined as:

| 7 |

Where is the background-corrected measured count-rate of the detector head at each source activity level.

Dead-time τ was obtained from a fit using gnuplot version 5.2.7 of a non-paralysable detector model:

| 8 |

Parameter error estimates were obtained from gnuplot version 5.2.7 as the asymptotic standard errors.

On two systems, Intevo 1 and Intevo 2, the methodology used here was validated against the dead-time measurement methodology presented by Gregory et al. [24]. The authors determined dead time by incrementally adding 131I to a Jaszczak phantom and performing 100 kcounts static images for each activity level.

No dead-time measurements were performed on the GE Discovery 670 as at the respective centre imaging will only be performed at imaging time points later than 48 h after the radioiodine administration. It is assumed that the activity level at such late imaging time points is low enough to ignore dead-time effects.

Results

System volume sensitivity

The system volume sensitivity values for the five systems are presented in Table 4. The system volume sensitivity value of the SPECT-only Siemens Symbia S was obtained using the Chang attenuation correction. System volume sensitivity of the Intevo Bold system was found to be approximately 18% higher compared to the two Intevo systems.

Table 4.

System volume sensitivity values for the five systems used in the MEDIRAD WP3 study

| System | System volume sensitivity [cps/MBq] |

|---|---|

| Siemens Intevo (1) | 63.0 ± 1.9 |

| Siemens Intevo (2) | 62.1 ± 1.9 |

| Siemens Intevo Bold | 73.5 ± 3.7 |

| Siemens Symbia S* | 55.6 ± 3.0 |

| GE Discovery 670 | 92.2 ± 2.8 |

*Chang’s attenuation correction

SPECT recovery coefficient

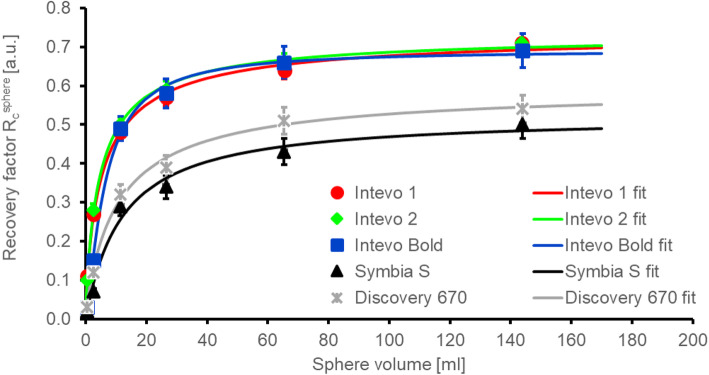

The recovery coefficients of the five systems are shown in Fig. 2 together with the respective fits using Eq. (5) in gnuplot version 5.2.7. A good agreement is observed between measured recovery coefficients and fits. The obtained fit parameters are summarised in Table 5.

Fig. 2.

Measured recovery coefficients (in arbitrary units—a.u.) for the five systems assessed here and the respective fits using Eq. (5)

Table 5.

Fit parameters for the recovery curve fitted using Eq. (5)

| System | Recovery curve fit parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rplateau | β | γ | |

| Siemens Intevo (1) | 0.74 ± 0.03 | 5.42 ± 0.77 | 0.82 ± 0.07 |

| Siemens Intevo (2) | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 4.75 ± 0.37 | 0.88 ± 0.04 |

| Siemens Intevo Bold | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 6.34 ± 0.48 | 1.15 ± 0.10 |

| Siemens Symbia S | 0.52 ± 0.05 | 11.95 ± 3.43 | 1.02 ± 0.23 |

| GE Discovery 670 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 10.75 ± 1.45 | 0.91 ± 0.07 |

The recovery curves for the Intevo Bold, Intevo 1 and Intevo 2 are similar whilst the recovery curve of the Symbia S is lower. The maximum observed absolute differences in the recovery curves, , for Intevo 1 and Intevo 2 were found to be 0.022 for a volume of 12 ml. For volumes larger than 10 ml, the two systems Intevo 1 and Intevo Bold have a similar of 0.018, indicating a good agreement between the curves. Nevertheless, for volumes smaller than 10 ml, the recovery curves of Intevo 1 and Intevo Bold vary by up to an of 0.103. Results for the Discovery 670 show that the recovery curve is lower than that of Intevo Bold and Intevo 1/2.

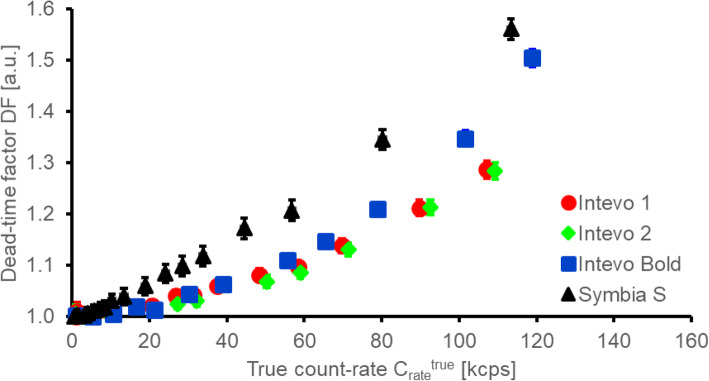

Dead-time factor

In Fig. 3, dead-time factors for the four systems that were used for high-activity 131I imaging in MEDIRAD are plotted against the true count-rate of the system. The maximum activity imaged of approximately 3700 MBq resulted in true count-rates of 115 ± 10 kilo counts-per-second (kcps) on the four systems. An activity of 1000 MBq in the field-of-view (FOV) was associated with true count rates of 30 ± 3 kcps.

Fig. 3.

Dead-time factor (in arbitrary units—a.u.) of the four Siemens systems used for the clinical part of the MEDIRAD study shown as a function of true count-rate of the system

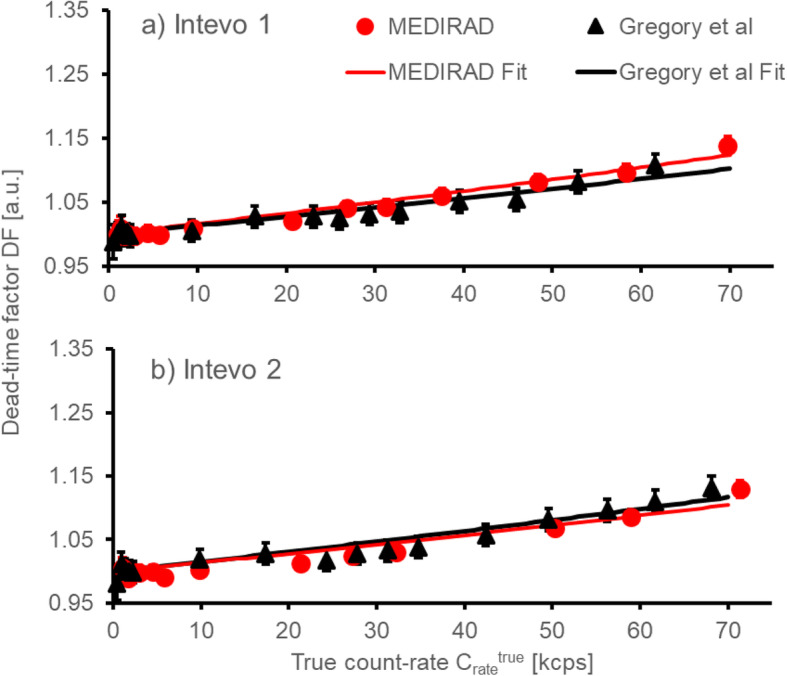

Figure 4 shows the comparison between dead-time factors obtained using the method proposed by Gregory et al. [24], which involves a series of acquisitions with increasing activity in a large volume uniform phantom, and the method used in the present study. An overall good agreement is found between the two methodologies on both systems assessed. The maximum absolute difference in dead-time factors at true count rates of up to approximately 65 kcps, corresponding to an activity of approximately 2700 MBq, was found to be ± 0.02. A fit of Eq. (8) to the dead time data of Intevo 1 measured using the methodology proposed here and the methodology used by Gregory et al. [24] resulted in dead times of 1.3 ± 0.1 and 1.5 ± 0.1 μs, respectively. For Intevo 2, dead times of 1.5 ± 0.1 and 1.4 ± 0.1 μs were obtained using the two methodologies, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the dead-time factors (in arbitrary units—a.u.) measured using the methodology by Gregory et al. [24] and the MEDIRAD methodology. The corresponding fits using a non-paralysable detector model (Eq. (8)) are shown as red and black lines, respectively

Discussion

The set-up of a quantitative imaging network, particularly involving centres in several countries, requires a certain degree of flexibility. The results presented here are for the set-up of the first European quantitative imaging network for radioiodine. Methodologies to set up a multi-national quantitative imaging network for radioiodine, which includes the assessment of system volume sensitivity, dead time and recovery coefficients were in part defined by restrictions based on the local interpretation of radiation protection laws in different countries, which for example prevented the use of large quantities of liquid radioiodine.

Due to the relatively low patient numbers in each centre, large imaging networks are required for any multi-centre clinical study aiming to recruit large numbers of patients in molecular radiotherapy. Results obtained here and by Gregory et al. [24] have provided evidence that dead-time factors are similar on gamma cameras from the same make and model. Similarly, if reconstruction protocols are standardised across the centres involved in a multi-centre study, recovery curves appear to be similar enough for matched makes and models to warrant the use of global, model-specific calibration factors as proposed by Gregory et al. [24].

In the present study, recovery curves were found to be similar for all three included Siemens SPECT/CT systems. The recovery curve of the SPECT only system is lower, potentially due to the use of Chang’s attenuation correction instead of CT attenuation correction. Differences between recovery curves of Siemens and GE systems assessed here are likely due to differences in the used high energy collimators by the two manufacturers (for comparison of septal thickness and hole length see ref. [24]), the crystal thickness of systems (3/8″ vs 5/8″) and the method of resolution recovery used in the manufacturer’s reconstruction software. The thicker crystal of the GE system is expected to result in a worse intrinsic resolution [32].

The observed difference in system volume sensitivity between the Intevo Bold and Intevo systems is a surprising result. Calculations, acquisition and reconstruction parameters were validated independently by two medical physicists. One possible explanation would be a difference in the software versions on the cameras and discussions with the manufacturer are ongoing. Further measurements on additional systems will be required to investigate this difference.

Using global calibration factors when using standardised acquisition and reconstruction parameters could potentially allow for a reduction in the site set-up measurements required before a centre can participate in a multi-centre clinical study. Acquisition and reconstruction methods are currently not standardised across centres and other studies involving molecular radiotherapy. Global calibration factors for system volume sensitivity and recovery coefficients could be determined if acquisition and reconstruction protocols would be standardised for new studies.

When using global calibration factors, validation measurements or dosimetry audits as required for external beam radiotherapy trials [33] will become more important. Those measurements range from simple sensitivity measurements to semi- or full-anthropomorphic phantoms [34–36] or testing of the full dosimetry chain [24]. In the present study, reconstructions are performed locally at the participating centres, which reduces the impact on the central dosimetry hub, but might increase site-dependent biases.

Dead-time factors measured using the methodology presented here and the one employed by Gregory et al. [24] showed good agreement within the associated uncertainties, which allows for further flexibility in future clinical studies. The methodology of Gregory et al. [24] allows for all dead-time measurements to be performed on a single day whilst the decaying source technique with a capsule of radioiodine requires measurements to be performed over several months. Nevertheless, the methodology proposed by Gregory et al. potentially leads to higher staff doses due to increased handling times of the phantom in the process of adding activity to the phantom in a step-by-step process. As multi-centre studies become more prevalent and involve centres in more countries, flexible approaches to these measurements might be required.

A limitation of the study is the small number of SPECT(/CT) systems included in the performance assessment. Two Siemens Intevo and one Siemens Intevo Bold SPECT/CT could be directly compared.

Conclusions

The first European quantitative imaging network for high-activity radioiodine has been set-up. The imaging network will determine, for the first time in a multi-centre setting, the range of absorbed doses delivered to healthy organs in patients undergoing thyroid ablation and aims to determine the threshold absorbed dose required for a successful ablation. Results presented here for two Siemens Intevo and one Siemens Intevo Bold provide additional support for the proposal to use global calibration parameters for cameras of the same make and model. In time, we hope to find that this could simplify the extension of the imaging network to other centres. There is an urgent need to standardise the acquisition and reconstruction parameters for studies involving dosimetry in molecular radiotherapy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the teams at the Royal Marsden Hospital, Universitätsklinikum Marburg, Universitätsklinikum Würzburg and Institute Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse Oncopole for their support in performing the site set-up measurements for the MEDIRAD study. Collaborating authors from the MEDIRAD WP3 Investigator Team: Andreas Buck, Naomi Clayton, Frédéric Courbon, Constantin Lapa, Markus Luster, Erick Mora-Ramirez, Kate Newbold, Sarah Schumann, Frederik Verburg, Lavinia Vija and Slimane Zerdoud.

Abbreviations

- ATA

American Thyroid Association

- EANM

European Association of Nuclear Medicine

- SNMMI

Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging

- ETA

European Thyroid Association

- DTC

Differentiated thyroid cancer

- WP3

MEDIRAD Work Package 3

- WB

Whole-body

- AC

Attenuation correction

- TEW

Triple-energy window

- kcounts

Kilo counts

- VOI

Volume-of-interest

- cps/MBq

Counts-per-second per MBq

- PMMA

Polymethyl methacrylate

- kcps

Kilo count per second

- FOV

Field-of-view

- HE

High energy

Authors’ contributions

All authors helped with the development of the site set-up protocols, JT and FL attended each centre to assist with the calibration measurements, UE, ML, SS, TS, JT-G and DV performed or assisted with the site set-up measurements at their individual hospitals, JT and FL performed the data analysis, JT and GF prepared the manuscript. All authors read the final manuscript and approved its publication.

Funding

NHS funding was provided to the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and the ICR. The MEDIRAD project has received funding from the Euratom research and training programme 2014-2018 under grant agreement No. 755523. The RTTQA group is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). We acknowledge infrastructure support from the NIHR Royal Marsden Clinical Research Facility Funding. This report is independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Availability of data and materials

Data can be provided upon a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethics approval or consent was required for this study as no human participants were involved.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ML has received research funding from IPSEN. MB consults for IPSEN, MEDPACE and Theragnostics.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jan Taprogge, Email: jan.taprogge@icr.ac.uk.

Francesca Leek, Email: francesca.leek@nhs.net.

Tino Schurrat, Email: schurrat@med.uni-marburg.de.

Johannes Tran-Gia, Email: tran_j@ukw.de.

Delphine Vallot, Email: Vallot.Delphine@iuct-oncopole.fr.

Manuel Bardiès, Email: manuel.bardies@inserm.fr.

Uta Eberlein, Email: Eberlein_U@ukw.de.

Michael Lassmann, Email: Lassmann_M@ukw.de.

Susanne Schlögl, Email: Schloegl_S@ukw.de.

Alex Vergara Gil, Email: alex.vergara-gil@inserm.fr.

Glenn D. Flux, Email: Glenn.Flux@icr.ac.uk

the MEDIRAD WP3 Investigator Team:

Andreas Buck, Naomi Clayton, Frédéric Courbon, Constantin Lapa, Markus Luster, Erick Mora-Ramirez, Kate Newbold, Sarah Schumann, Frederik Verburg, Lavinia Vija, and Slimane Zerdoud

References

- 1.Tuttle RM, Ahuja S, Avram AM, Bernet VJ, Bourguet P, Daniels GH, et al. Controversies, consensus, and collaboration in the use of 131I therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer: a joint statement from the American Thyroid Association, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the European Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2019;29(4):461–470. doi: 10.1089/thy.2018.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hackshaw A, Harmer C, Mallick U, Haq M, Franklyn JA. 131I activity for remnant ablation in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer: a systematic review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(1):28–38. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flux GD, Haq M, Chittenden SJ, Buckley S, Hindorf C, Newbold K, et al. A dose-effect correlation for radioiodine ablation in differentiated thyroid cancer. EJNNMI. 2010;37(2):270–275. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koral KF, Adler RS, Carey JE, Beierwaltes WH. Iodine-131 treatment of thyroid cancer: absorbed dose calculated from post-therapy scans. J Nucl Med. 1986;27(7):1207–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maxon HR, Thomas SR, Samaratunga RC. Dosimetric considerations in the radioiodine treatment of macrometastases and micrometastases from differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 1997;7(2):183–187. doi: 10.1089/thy.1997.7.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connell ME, Flower MA, Hinton PJ, Harmer CL, McCready VR. Radiation dose assessment in radioiodine therapy. Dose-response relationships in differentiated thyroid carcinoma using quantitative scanning and PET. Radiother Oncol. 1993;28(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90180-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdi YE, Macapinlac H, Larson SM, Erdi AK, Yeung H, Furhang EE, et al. Radiation dose assessment for I-131 therapy of thyroid cancer using I-124 PET imaging. Clinical positron imaging. 1999;2(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(99)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flower MA, Schlesinger T, Hinton PJ, Adam I, Masoomi AM, Elbelli MA, et al. Radiation dose assessment in radioiodine therapy. 2. Practical implementation using quantitative scanning and PET, with initial results on thyroid carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 1989;15(4):345–357. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(89)90081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wierts R, Brans B, Havekes B, Kemerink GJ, Halders SG, Schaper NN, et al. Dose-response relationship in differentiated thyroid cancer patients undergoing radioiodine treatment assessed by means of 124I PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(7):1027–1032. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.168799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verburg FA, Lassmann M, Mader U, Luster M, Reiners C, Hanscheid H. The absorbed dose to the blood is a better predictor of ablation success than the administered 131I activity in thyroid cancer patients. EJNMMI. 2011;38(4):673–680. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1689-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hänscheid H, Lassmann M, Luster M, Thomas SR, Pacini F, Ceccarelli C, et al. Iodine biokinetics and dosimetry in radioiodine therapy of thyroid cancer: procedures and results of a prospective international controlled study of ablation after rhTSH or hormone withdrawal. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(4):648–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.EMA. ICH Topic E9: Note for guidance on statistical considerations in the design of clinical trials, CPMP/ICH/363/96. 1998.

- 14.Taprogge J, Leek F, Flux GD. Physics aspects of setting up a multicenter clinical trial involving internal dosimetry of radioiodine treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer. QJNMMI. 2019;63(3):271–277. doi: 10.23736/S1824-4785.19.03202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bardies M, Flux GD. Defining the role for dosimetry and radiobiology in combination therapies. EJNMMI. 2013;40(1):4–5. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewaraja YK, Ljungberg M, Green AJ, Zanzonico PB, Frey EC. MIRD pamphlet no. 24: guidelines for quantitative 131I SPECT in dosimetry applications. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(12):2182–2188. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.122390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gear J, Chiesa C, Lassmann M, Mínguez Gabiña P, Tran-Gia J, Stokke C, et al. EANM Dosimetry Committee series on standard operational procedures for internal dosimetry for 131I mIBG treatment of neuroendocrine tumours. EJNMMI Phys. 2020;7(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s40658-020-0282-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman BE, Grosev D, Buvat I, Coca Perez MA, Frey EC, Green A, et al. Multi-centre evaluation of accuracy and reproducibility of planar and SPECT image quantification: an IAEA phantom study. Z Med Phys. 2017;27(2):98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.zemedi.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wevrett J, Fenwick A, Scuffham J, Johansson L, Gear J, Schloegl S, et al. Inter-comparison of quantitative imaging of lutetium-177 (177Lu) in European hospitals. EJNMMI Phys. 2018;5:17. doi: 10.1186/s40658-018-0213-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters SMB, Meyer Viol SL, van der Werf NR, de Jong N, van Velden FHP, Meeuwis A, et al. Variability in lutetium-177 SPECT quantification between different state-of-the-art SPECT/CT systems. EJNMMI Physics. 2020;7(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s40658-020-0278-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters SMB, van der Werf NR, Segbers M, van Helden FHP, Wierts R, Blokland KAK, et al. Towards standardization of absolute SPECT/CT quantification: a multi-center and multi-vendor phantom study. EJNMMI Phys. 2020;6:29. doi: 10.1186/s40658-019-0268-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickson JC, Tossici-Bolt L, Sera T, de Nijs R, Booij J, Bagnara MC, et al. Proposal for the standardisation of multi-centre trials in nuclear medicine imaging: prerequisites for a European 123I-FP-CIT SPECT database. EJNMMI. 2012;39(1):188–197. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wadsley J, Gregory R, Flux G, Newbold K, Du Y, Moss L, et al. SELIMETRY-a multicentre I-131 dosimetry trial: a clinical perspective. Br J Radiol. 2017;90(1073):20160637. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregory RA, Murray I, Gear J, Leek F, Chittenden S, Fenwick A, et al. Standardised quantitative radioiodine SPECT/CT imaging for multicentre dosimetry trials in molecular radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2019;64(24):245013. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab5b6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MEDIRAD. http://www.medirad-project.eu/. Accessed Jun 2020.

- 26.Hoffman EJ, Huang SC, Phelps ME. Quantitation in positron emission computed tomography: 1. Effect of object size. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1979;3(3):299–308. doi: 10.1097/00004728-197906000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busemann Sokole E, Plachcinska A, Britten A, Lyra Georgosopoulou M, Tindale W, Klett R. Routine quality control recommendations for nuclear medicine instrumentation. EJNMMI. 2010;37(3):662–671. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang L. A method for attenuation correction in radionuclide computed tomography. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 1978;25(1):638–643. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gear J, Cox MG, Gustafsson J, Gleisner KS, Murray I, Glatting G, et al. EANM practical guidance on uncertainty analysis for molecular radiotherapy absorbed dose calculations. EJNMMI. 2018;45:2456–2474. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gadd R, Baker M, Nijran KS, Owens S, Thomson W, Woods MJ, et al. A national measurement good practice guide no. 93 protocol for establishing and maintaining the calibration of medical radionuclide calibrators and their quality control. http://eprintspublications.npl.co.uk/3661/1/mgpg93.pdf. Accessed Jun 2020.

- 31.Liu B, Huang R, Kuang A, Zhao Z, Zeng Y, Wang J, et al. Iodine kinetics and dosimetry in the salivary glands during repeated courses of radioiodine therapy for thyroid cancer. Med Phys. 2011;38(10):5412–5419. doi: 10.1118/1.3602459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cherry SR, Sorenson JA, Phelps ME. Physics in nuclear medicine. 4. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kron T, Haworth A, Williams I. Dosimetry for audit and clinical trials: challenges and requirements. J Phys Conf Ser. 2013;444:012014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gear JI, Cummings C, Craig AJ, Divoli A, Long CDC, Tapner M, et al. Abdo-Man: a 3D-printed anthropomorphic phantom for validating quantitative SIRT. EJNMMI Physics. 2016;3(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s40658-016-0151-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gear JI, Long C, Rushforth D, Chittenden SJ, Cummings C, Flux GD. Development of patient-specific molecular imaging phantoms using a 3D printer. Med Phys. 2014;41(8):082502. doi: 10.1118/1.4887854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price E, Robinson AP, Cullen DM, Tipping J, Calvert N, Hamilton D, et al. Improving molecular radiotherapy dosimetry using anthropomorphic calibration. Physica Medica. 2019;58:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be provided upon a reasonable request to the corresponding author.