Abstract

T cell receptor signaling, together with cytokine-induced signals, can differentially regulate RNA processing to influence T helper versus regulatory T cell fate. Protein kinase C family members have been shown to function in alternative splicing and RNA processing in various cell types. T cell-specific protein kinase C theta, a molecular regulator of T cell receptor downstream signaling, has been shown to phosphorylate splicing factors and affect post-transcriptional control of T cell gene expression. In this study, we explored how using a synthetic cell-penetrating peptide mimic for intracellular anti-protein kinase C theta delivery fine-tunes differentiation of induced regulatory T cells through its differential effects on RNA processing. We identified protein kinase C theta signaling as a critical modulator of two key RNA regulatory factors, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L (hnRNPL) and protein-l-isoaspartate O-methyltransferase-1 (PCMT1), and loss of protein kinase C theta function initiated a “switch” in post-transcriptional organization in induced regulatory T cells. More interestingly, we discovered that protein-l-isoaspartate O- methyltransferase-1 acts as an instability factor in induced regulatory T cells, by methylating the forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) promoter. Targeting protein-l-isoaspartate O-methyltransferase-1 using a cell-penetrating antibody revealed an efficient means of modulating RNA processing to confer a stable regulatory T cell phenotype.

Keywords: cell-penetrating peptide mimics, intracellular antibody delivery, PKCθ, PCMT1, hnRNPL, induced regulatory T cell, FOXP3, alternative splicing

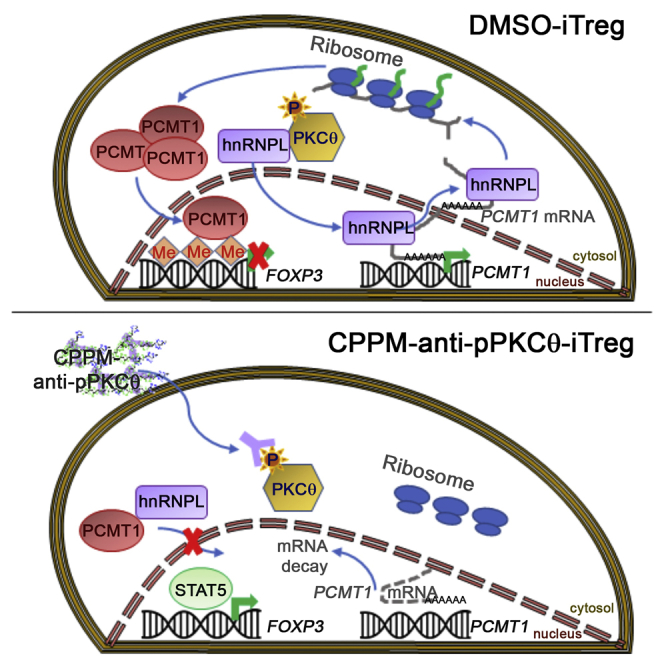

Graphical Abstract

Using cell-penetrating peptide mimics to deliver polyclonal anti-pPKCθ antibodies into human CD4 T cells reveals that the T cell-specific kinase PKCθ regulates alternative splicing and RNA export of the methyltransferase PCMT1 in induced regulatory T cells and modulates FOXP3 TSDR methylation.

Introduction

Immunological signals emanating from the T cell receptor (TCR) culminate in translation of mRNA in immune cells. Depending on the input, alterations in this process can be mediated by RNA binding protein (RBP) assemblies to coordinate downstream biological outcomes, such as T cell activation, tolerance, and plasticity. Modifications in RBP-mediated post-transcriptional regulation can influence cellular reactivity during inflammatory responses and autoimmunity.1 RBPs include two main classes of proteins: heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) that bind to splicing silencers, and serine-arginine-rich (SR) proteins that bind to splicing enhancers.2, 3, 4 Initially discovered as spliceosome components regulating alternative splicing, these proteins are involved in numerous other cellular processes such as transcription, chromatin dynamics, mRNA stability, mRNA nuclear export, and translation.5,6 These multifunctional RBPs remain bound to mRNA, facilitating nucleation of other regulatory proteins that aid in mRNA export to the cytoplasm and subsequent translation.4,7,8 By necessity, these proteins are tightly regulated, including by phosphorylation in response to extracellular stimuli, which can alter their activity and subcellular localization.9, 10, 11, 12

TCR-mediated signaling pathways effect multiple changes in cell morphology and function through alternative splicing and by orchestrating interactions between positively and negatively regulating RBPs and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs).1, 2, 3,6 Many immunological effectors, including cytokines and chemokines, harbor 3′ UTR regulatory elements that enable fine-tuning of immunological responses based on cellular requirements.13, 14, 15 Alternative splicing and RNA processing can be regulated in a tissue- and cell-specific fashion, downstream of environmental cues.16, 17, 18 However, our full understanding of the molecular mechanisms that convey differences in post-transcriptional regulation remain incomplete.

For example, alternative splicing of the leukocyte surface protein protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type C (encoded by PTPRC) and commonly referred to as CD45 represents one well-characterized example of how external stimuli result in changes in expression of alternatively spliced proteins.19, 20, 21 Protein kinase C (PKC) and Ras signaling induce exon skipping within PTPRC, generating alternate forms of CD45 that concomitantly exhibit reduced phosphatase activity.19,22,23 Different CD45 isoforms are generated by multi-protein complexes of RBPs, including hnRNPL.24 Studies using immune cells have focused on hnRNPL as a critical nuclear RBP, with four RNA recognition motifs and capable of mediating basal splicing, mRNA stability, and nuclear export.25, 26, 27, 28 hnRNPL binds to CA-repeat motifs and CA-rich elements, thereby repressing exon skipping.26,29 T cell activation can induce post-translational modifications of hnRNPL to increase its silencing activity.30,31 Because hnRNPL activity is higher in resting cells, these cells express primarily the longer CD45 isoforms, CD45RA and or CD45RB. In activated and memory T cells, in which hnRNPL activity is low, increased levels of the shortest isoform, CD45RO, predominate.21 CD45 isoform expression in regulatory T cells (Tregs) has also been associated with FOXP3 stability and Treg suppressive capacity, as well as with Treg homing in vivo.32 Furthermore, differential splicing and mRNA processing regulated by TCR and hnRNPL are key drivers of T helper versus Treg fate choice. hnRNPL knockdown suppressed Treg induction, suggesting that hnRNPL, as an mRNA regulatory protein, is critical to maintaining the integrity of Treg differentiation programs.33

Tregs function to control immune responses and maintain self-tolerance within the immune system.34,35 Demethylation of the Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR), located within the intronic sequence of the FOXP3 promoter, is a prerequisite for stable FOXP3 expression and Treg suppressive function.36, 37, 38 Our previous studies demonstrated that we could modulate T cell fate by delivering a cell-penetrating antibody directed against phosphorylated PKCθ (pPKCθ), and intracellular anti-pPKCθ delivery into human CD4 T cells prior to in vitro iTreg differentiation generated highly stable induced Tregs (iTregs) with a unique phenotype.39 Inhibiting PKCθ function by constraining its intracellular movement in iTregs resulted in superior suppressive capacity and correlated with unusual transcriptional changes, both in vitro and in vivo. This led us to investigate how these transcriptional changes were regulated by PKCθ during iTreg differentiation. An interesting, potential link between PKCθ and transcriptional diversity has been explored in T cells.40, 41, 42 PKCθ directly phosphorylates the splicing factor SC35 within its RNA recognition motif and SR domain.40,43 PKCθ and SC35 colocalize with RNA polymerase II, as well as with active histone marks, to enhance transcriptional elongation.40 Moreover, SC35 binds to exonic splicing enhancers and coordinates alternative splicing, RNA stability, mRNA export, and translation.44, 45, 46, 47 Intriguingly, a FOXP3 stabilizing protein, TIP60, was shown to promote SC35 degradation via acetylation at lysine residue 52, in close proximity to PKCθ phosphorylation sites, suggesting that PKCθ may act to regulate splicing factors in the context of Treg suppressive function.48,49 Given that PKCθ phosphorylates SC35 and controls epigenetic and transcriptional regulation in T cells, we hypothesized that PKCθ may regulate alternative splicing and, furthermore, RNA processing during iTreg differentiation.

In this study, we show that intracellular anti-pPKCθ delivery into CD4 T cells prior to iTreg differentiation effectively “switches” alternative splicing and RNA processing programs to favor stable over plastic iTreg phenotypes. PKCθ critically modulates two key RNA regulatory factors, hnRNPL and protein-l-isoaspartate O-methyltransferase-1 (PCMT1), thereby reprogramming mRNA splicing, stability, nuclear export, and translational control. More interestingly, we demonstrate that PCMT1 acts as a Treg instability factor by methylating the FOXP3 promoter. Targeting PCMT1 using a cell-penetrating antibody revealed an efficient means for modulating RNA processing to confer stable Treg function.

Results

Ex Vivo Anti-pPKCθ Delivery into iTregs Modulates Splicing Regulatory Proteins and RNA Processing

PKCθ has been described as a negative regulator of Treg differentiation. It has also been linked to the splicing machinery in CD4 T cells, through its demonstrated phosphorylation of the splicing regulator SC35.40 Therefore, we sought to determine whether PKCθ may affect iTreg differentiation by modulating regulatory and splicing proteins. We previously showed that we could modulate pPKCθ activity, ex vivo, using synthetic protein transduction domain mimics to efficiently carry a functional antibody across the membrane of human CD4 T cells.50 In this study, we utilized this same approach to probe the function of PKCθ during ex vivo iTreg differentiation. We cultured human CD4 T cells with or without cell-penetrating peptide mimics (CPPMs) complexed to anti-pPKCθ in the presence of iTreg polarizing or with DMSO only, to generate anti-pPKCθ-iTregs or DMSO-iTregs, respectively.39 For comparison, we also cultured CD4 T cells with or without CPPM-anti-pPKCθ for the same length of time, but in the absence of iTreg polarizing conditions, to generate anti-pPKCθ-conventional T cells (Tconvs) and DMSO-Tconvs, respectively. After 5 days of differentiation, we assessed the cytosolic and nuclear distribution of phosphorylated (p)SC35 (Figure 1A). We observed that pSC35 expression was abrogated in iTregs differentiated in the presence of anti-pPKCθ. This was not entirely unexpected, as SC35 has been reported to be a substrate of PKCθ,40 and loss of pSC35 confirms that anti-pPKCθ delivery attenuates PKCθ activity.

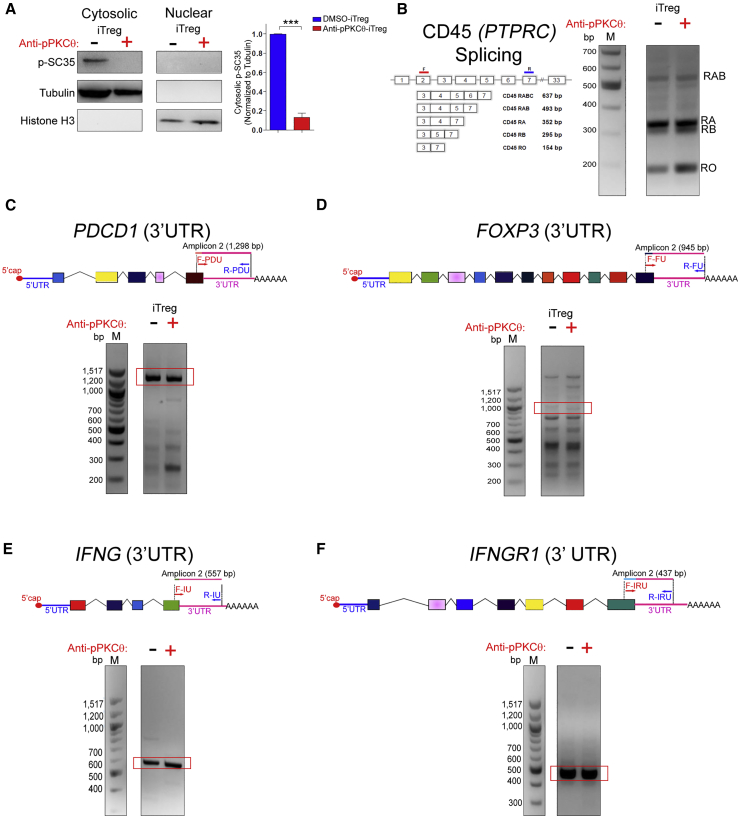

Figure 1.

Ex Vivo Anti-pPKCθ Delivery into iTregs Modulates Splicing Regulatory Proteins and RNA Processing

(A) Cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution of pSC35 in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs was analyzed by immunoblotting. Normalized densities for cytoplasmic pSC35 were quantified relative to tubulin expression. (B) Alternative splicing of CD45 (PTPRC) was analyzed in iTregs using RT-PCR. Primers were designed to assess 3′ UTR processing using RT-PCR and covered sequences from the last exon to the polyadenylation site. (C–F) Results and cartoon representations are shown for (C) PDCD1, (D) FOXP3, (E) IFNG, and (F) IFNGR1. Red frames indicate expected amplicon sizes for mature mRNA with its 3′ UTR. Data represent the mean ± SEM of two or three independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test was used for analysis. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Since the SC35 splicing regulator was affected by anti-pPKCθ delivery to iTregs, we questioned whether there were differences in alternative splicing or 3′ UTR processing in key iTreg molecules. Properly generating 3′ UTRs is critical for mRNA stability, since 3′ UTRs include recognition motifs for RBPs that may stabilize or destabilize mRNA through their influences on mRNA degradation and silencing. In addition, shorter 3′ UTR lengths have been associated with stable mRNA production and increased protein translation in a signal-dependent manner.51 Immune cells recruit specific RBPs to sites of translation to form riboclusters. Arrangement of RBPs on the 3′ UTR elements (AU-rich and CA-rich elements) in the riboclusters determine whether mRNA will be translated or directed to nonsense-mediated decay. CD45 splicing has been extensively studied in T cells and shown to be regulated by hnRNPL. Therefore, we first examined CD45 splicing in iTregs, as a proof-of-concept target. We noted that anti-pPKCθ delivery increased RB and RO forms both in iTregs and Tconvs, compared to untreated cells (Figures 1B and S1A). In a companion study, we showed that anti-pPKCθ-treated iTregs displayed unique characteristics, including higher FOXP3, PD1, and interferon (IFN)γ expression.39 Given the fact that FOXP3 and PD1 reportedly undergo alternative splicing,52, 53, 54 we asked whether anti-pPKCθ delivery affected mRNA processing of these and other key iTreg genes. We analyzed the splicing patterns and 3′ UTR lengths of PDCD1, FOXP3, IFNG, and IFNGR1. Conventional mRNAs for those genes consist of exons 1-2-3-4-5 (PDCD1), exons 2-3-4-5 (FOXP3), 4 exons (IFNG), and 7 exons (IFNGR1). We observed similar splicing patterns for all four genes in iTregs with or without anti-pPKCθ treatment (Figures S1B–S1E). Anti-pPKCθ delivery into Tconvs produced similar spliced forms, except for FOXP3 mRNA, which showed truncated sequences following anti-pPKCθ treatment (Figure S1C). Interestingly, anti-pPKCθ delivery affected 3′ UTR processing in a gene-specific manner. When we evaluated these four genes in iTregs and Tconvs, we detected PDCD1 mRNA variants with markedly shorter 3′ UTR lengths following anti-pPKCθ treatment compared to DMSO-iTregs (Figures 1C and S1F), while FOXP3, IFNG, and IFNGR1 3′ UTR lengths did not change after antibody treatment (Figures 1D–1F and S1G–S1I). Expression of a shorter 3′ UTR sequence in PDCD1 is consistent with increased expression of surface PD1 observed on iTregs differentiated following anti-pPKCθ delivery.39Collectively, these results suggest that PKCθ modulates splicing regulators and RNA processing in a cell- and gene-specific context.

Ex Vivo Treatment of iTregs Conveys Durable Tissue-, Cell-, and Gene-Specific Modulation of RNA Processing In Vivo

We noted increased CD45RB and CD45RO expression in iTregs differentiated following ex vivo anti-pPKCθ delivery, in the absence of robust differences in alternative splicing of PDCD1, FOXP3, IFNG, or IFNGR1. However, in vivo, iTregs can behave differently due to their differential trafficking and exposure to cytokines. Furthermore, reports suggest that these influences and others may prime Tregs for additional alternative splicing events in response to external signals. We explored this possibility by analyzing the expression of CD45 (PTPRC), PDCD1, FOXP3, IFNG, and IFNGR1 in iTregs isolated from the bone marrow (BM) and spleen of mice, used in a humanized model of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD).39 In this pre-clinical model, lethal GvHD results from acute BM infiltration of destructive immune cells, approximately 3 weeks after human peripheral blood mononuclear cells are transferred into lightly irradiated nonobese diabetic (NOD).Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice. In our companion study, we determined that administering anti-pPKCθ-iTregs at the time of disease induction was highly efficacious in preventing GvHD. We detected high numbers of anti-pPKCθ-iTregs in the BM at the peak day of the disease (day 17), and these iTregs exhibited a unique and stable gene expression pattern.39 To determine whether alternate RNA processing leads to more stable mRNA variants in these iTregs, we adoptively transferred anti-pPKCθ-iTregs or DMSO-iTregs into humanized mice on the day of GvHD induction and analyzed RNA processing in iTregs on day 17, at the peak of disease. We used magnetic beads to purify cells collected from BM and spleen based on CD4, CD25, and CD127 expression. In contrast with in vitro results, anti-pPKCθ-iTregs isolated from BM showed increased expression of the CD45RA/RB isoforms, compared to DMSO-iTregs, while iTregs isolated from spleens had comparable expression of CD45 isoforms, regardless of treatment during differentiation (Figure 2A). When we analyzed naive T cells, we found that they expressed similar patterns of CD45 splice variants in both tissues, regardless of iTreg treatment (Figure S2A). These data suggested that ex vivo anti-pPKCθ delivery into iTregs alters CD45 splicing and is iTreg-specific. Moreover, increased CD45RA/RB expression by anti-pPKCθ-iTregs is consistent with reports showing that this population of iTregs preferentially migrates to the BM.32

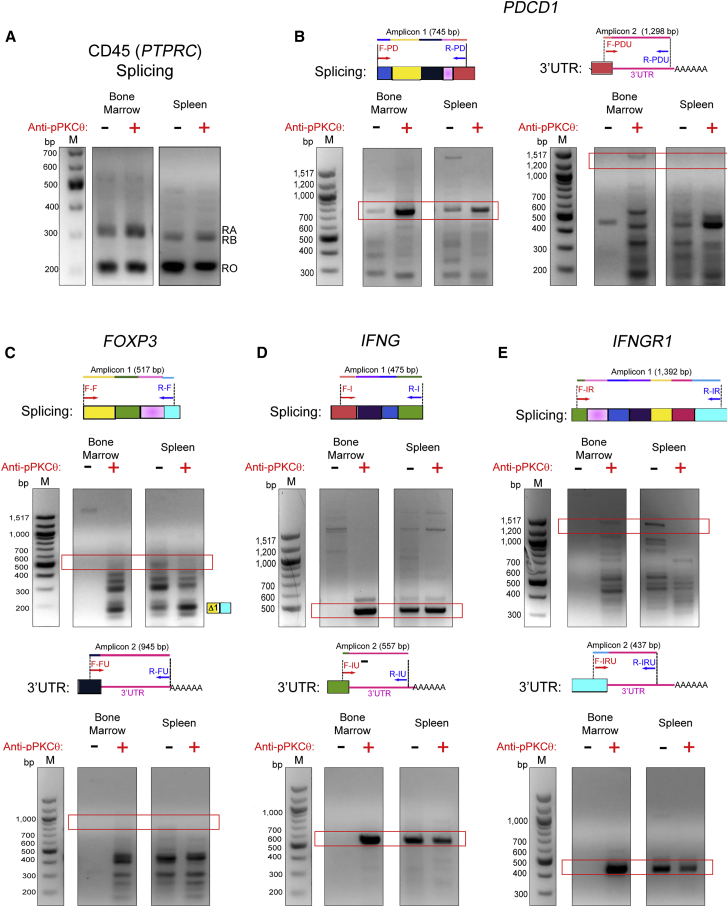

Figure 2.

Ex Vivo Treatment of iTregs Conveys Durable Tissue-, Cell-, and Gene-Specific Modulation of RNA Processing In Vivo

hPBMCs were transferred on day 0 together with anti-pPKCθ-iTregs (or DMSO-iTregs) at a ratio of 3:1. On day 17, tissues were harvested and iTregs were isolated based on CD4+, CD25+, CD127− expression, using magnetic beads. Total RNA was extracted from ex vivo-treated iTregs recovered from BM and spleen on day 17. (A–E) RT-PCR was used to evaluate alternatively spliced (A) CD45 (PTPRC), and alternative splicing and 3′ UTR processing of (B) PDCD1, (C) FOXP3, (D) IFNG, and (E) IFNGR1. Red frames indicate the expected amplicon size, and the cartoon representation for expected amplicon size is shown for each gene. Data are representative of three independent experiments from five mice per condition.

When we further assessed iTregs recovered from the BM and spleens of diseased mice, we found that, in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, both PDCD1 and FOXP3 displayed differences in mRNA expression. Whereas PDCD1 transcripts were nearly undetectable in BM-infiltrating DMSO-iTregs, anti-pPKCθ-iTregs isolated from BM and spleen showed robust expression of PDCD1 as well as extensive editing in the 3′ UTR length, suggesting that transcripts generated in these cells may be more stable compared to DMSO-iTregs (Figure 2B). Quite surprisingly, the expression level, as well as the expression pattern, of FOXP3 splice variants in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs recovered from the BM also differed significantly from those of DMSO-iTregs. iTregs isolated from spleens of diseased mice showed minimal variability in FOXP3 isoform expression, regardless of how the iTregs were generated (Figure 2C). While we were unable to amplify FOXP3 3′ UTR of the expected size in BM-infiltrating iTregs, we did detect shorter 3′ UTR variants only in BM-resident anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, again suggesting that unique 3′ UTR editing also occurs in these cells (Figure 2C). Naive T cells recovered from the BM and spleen of diseased mice showed comparable expression patterns of PDCD1 and FOXP3 splice variants and 3′ UTR editing, with the exception of naive T cells isolated from spleens of DMSO-iTreg-treated mice, which showed multiple short isoforms of FOXP3 (Figures S2B and S2C).

Consistent with the alterations in PDCD1 and FOXP3 that we observed to be unique to BM-infiltrating anti-pPKCθ-treated iTregs, we also noted distinct and exclusive mRNA splicing and 3′ UTR editing of IFNG and IFNGR1 in these cells as well (Figures 2D and 2E). We could amplify IFNG and IFNGR1 splice variants and 3′ UTR transcripts of the expected amplicon sizes in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs isolated from BM, but not from BM-infiltrating DMSO-iTregs (Figures 2D and 2E). We also noted some tissue-specific differences in the isoform expression and 3′ UTR length in these genes, amplified from naive T cells recovered from BM and spleens of mice (Figures S2B–S2E). Additionally, although we detected IFNG mRNA splice variants in naive T cells from BM (Figure S2D), they were lacking IFNGR1 mRNA, due to differential 3′ UTR editing (Figure S2E). This raises the intriguing prospect that iTregs may exert a cell-extrinsic effect on naive T cells that makes them refractory to the effects of IFNγ signaling, although further experimentation is needed to test this possibility. Altogether, these data suggest that alternative splicing and 3′ UTR shortening of key iTreg genes were selectively modulated in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, during in vivo immune responses, and these occurred in a tissue-, cell-, and gene-specific fashion.

In iTregs, PCMT1 Is Regulated through Post-translational and Post-transcriptional Processes

The protein repair enzyme, PCMT1, repairs damaged proteins by methylating the carboxyl group of l-isoaspartate or d-aspartyl residues.55 PCMT1 can also regulate critical cellular processes such as RNA maturation, stability, export, histone homeostasis, and post-translational control.56, 57, 58, 59 PCMT1 shares similarities with two other methyltransferases shown to methylate proteins and RNA: S-adenosylmethionine-dependent protein arginine methyltransferase (PRMT) and PRIP-interacting protein with methyltransferase domain (PIMT), respectively. Therefore, we investigated PCMT1 regulation in the context of iTreg differentiation with and without anti-pPKCθ delivery.

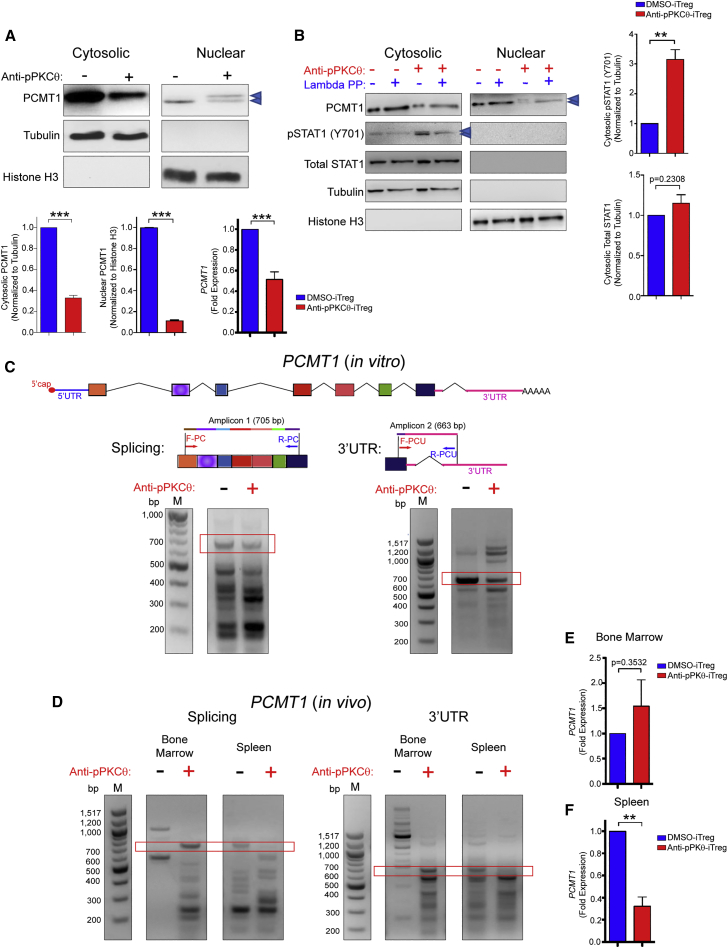

PCMT1 was expressed at high levels in the cytosol but we could also detect low levels in the nucleus of DMSO-iTregs (Figure 3A). Following anti-pPKCθ delivery, cytosolic and nuclear PCMT1 levels were significantly diminished, as was gene expression (Figure 3A). We also noted decreased cytosolic PCMT1 expression and altered splice variants in anti-pPKCθ-Tconvs (Figures S3A–S3C). Interestingly, we detected two separate PCMT1 bands in the nuclear lysates only of anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, raising the possibility that nuclear PCMT1 in these cells is a phosphorylated species (Figure 3A). We generated additional cytosolic and nuclear samples and treated half of each sample with λ-phosphatase, to determine whether the upper band represented phosphorylated PCMT1. We detected significantly higher pSTAT1 (Y701) levels in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs (Figure 3B), consistent with reports of elevated pSTAT1 in highly suppressive iTregs. Therefore, we also included pSTAT1 (Y701) as an internal control. As expected, pSTAT1 was not detected following phosphatase treatment (Figure 3B). Similarly, the upper band of nuclear PCMT1 was undetectable in nuclear lysates following phosphatase treatment (Figures 3A and 3B). These results suggest that one means by which pPKCθ may negatively regulate iTreg differentiation is by suppressing PCMT1 phosphorylation, which may further impact its nuclear function.

Figure 3.

In iTregs, PCMT1 Is Regulated through Post-translational and Post-transcriptional Processes

(A) PCMT1 protein in cytosolic and nuclear extracts was detected using immunoblotting, and band intensity was quantified relative to tubulin and histone H3 expression, respectively, using ImageJ software. (B) λ-Phosphatase treatment was used to confirm PCMT1 phosphorylation. pSTAT1 was used as a phosphorylation control. Total STAT1 and pSTAT1 (Y701) were quantified using ImageJ software. (C) PCMT1 splicing and 3′ UTR lengths were analyzed using RT-PCR in ex vivo-treated iTregs. (D) PCMT1 splicing and 3′ UTR length were analyzed using RT-PCR and PCMT1 gene expression was quantified using qPCR in iTregs isolated from (E) BM and (F) spleen of iTreg-treated mice on day 17. Red frames indicate the expected amplicon sizes. Data represent the mean ± SEM of two or three independent experiments. For in vivo experiments, four mice per group were used. An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test was used for analysis. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Having detected differences in RNA splice variants in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, in vitro and in vivo (Figures 1 and 2, respectively), we next asked whether anti-pPKCθ delivery affected RNA processing of PCMT1 in iTregs, as well. Conventional PCMT1 mRNA has seven exons with a 3′ UTR that contains approximately 700 bp. In anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, we observed evidence of exon skipping in PCMT1 transcripts, detecting shorter mRNA variants together with longer-than-expected 3′ UTRs (Figure 3C). We were also interested in whether anti-pPKCθ treatment conveyed durable differences in iTregs recovered from the BM and spleens of mice in our humanized model of GvHD. Strikingly, we detected markedly different splice variants of PCMT1, as well as shorter 3′ UTR lengths, in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs isolated from BM, while iTregs in the spleen displayed similar patterns of PCMT1 processing, regardless of prior treatment (Figure 3D). We did not detect significantly diminished PCMT1 in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs recovered from the BM; however, PCMT1 expression was significantly downregulated in anti-pPKCθ iTregs found in the spleen (Figure 3E). Naive T cells showed comparable levels of PCMT1 in the BM, but significantly reduced transcripts in the spleen, of mice treated with anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, compared to mice that received DMSO-iTregs (Figure S3D). Interestingly, the PCMT1 splicing pattern in naive T cells was reversed compared to in vivo-recovered iTregs (Figure S3E). Altogether, these data demonstrate that in iTregs, PKCθ plays an important role in regulating the protein methyltransferase, PCMT1, both post-translationally and post-transcriptionally.

Ex Vivo Anti-PCMT1 Delivery Enhances iTreg Differentiation

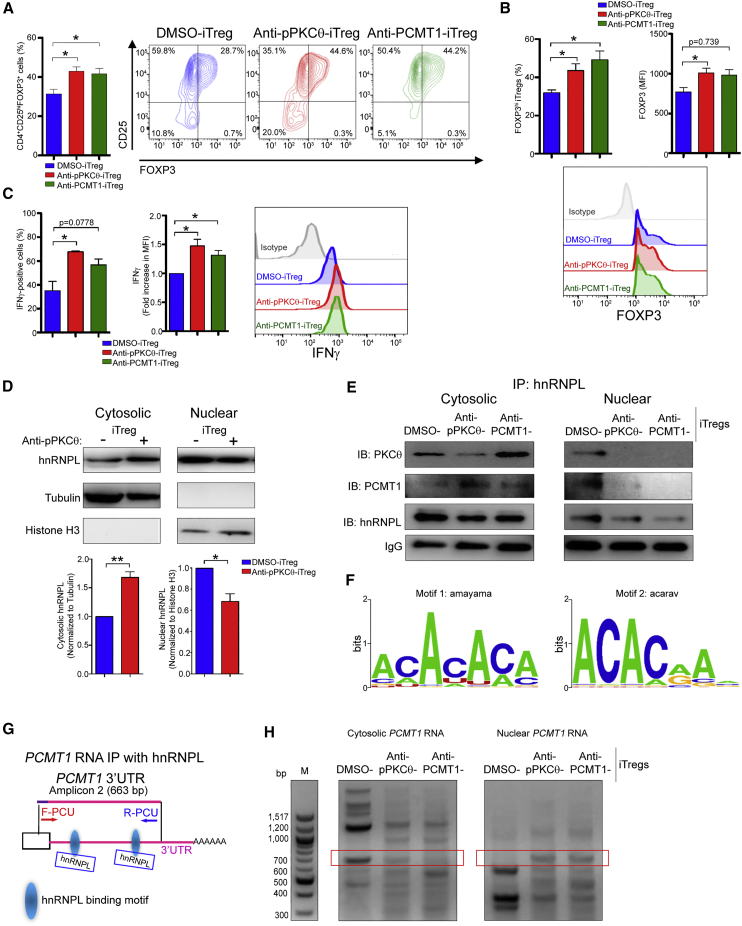

We sought to further investigate how modulating PCMT1 affected mRNA-RBP interactions in iTregs. To do this, we delivered anti-PCMT1 into human CD4 T cells and then differentiated the cells, ex vivo, toward an iTreg phenotype (anti-PCMT1-iTregs). We then compared the phenotype of anti-PCMT1-iTregs to anti-PKCθ-iTregs. Interestingly, we observed a significant increase in the percentage of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ iTregs generated following anti-PCMT1 delivery, and which was comparable to the percentage of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ iTregs treated with anti-pPKCθ (Figure 4A). In addition, relative to DMSO-iTregs, FOXP3 expression was higher in anti-pPKCθ- and in anti-PCMT1-treated iTregs, with each treatment producing a greater percentage of iTregs that were FOXP3hi, compared to DMSO-iTregs (Figure 4B). We previously found that anti-PKCθ-iTregs expressed significantly more IFNγ than did DMSO-iTregs, a characteristic consistent with a unique population of highly suppressive Tregs.39,60,61 Therefore, we also assessed IFNγ expression in anti-PCMT1 iTregs. Delivering either anti-pPKCθ or anti-PCMT1 into CD4 T cells increased the percentage of IFNγhi-expressing iTregs and suggests that PKCθ and PCMT1 operate within the same pathway to regulate iTreg IFNγ production (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Ex Vivo Anti-PCMT1 Delivery Enhances iTreg Differentiation

(A) Percentages of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells with representative scatterplots following ex vivo treatment with cell-penetrating anti-pPKCθ or anti-PCMT1 delivery. (B) Percentage of FOXP3high iTregs and FOXP3 median fluorescent intensities (MFIs) together with their representative histograms of iTregs treated as in (A). (C) Percentage of IFNγ+ iTregs and fold increase in IFNγ MFI, together with representative histograms, of iTregs treated as in (A). (D) Cytoplasmic and nuclear distributions of hnRNPL in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs were analyzed by immunoblotting. Normalized densities for cytoplasmic and nuclear hnRNPL were quantified relative to tubulin and histone H3 expression, respectively. (E) Cytosolic and nuclear association of hnRNPL with PKCθ and PCMT1 in iTregs was determined using co-immunoprecipitation. (F) Predicted hnRNPL RNA binding motifs using the Catalog of Inferred Sequence Binding Preferences of RNA binding proteins (CISBP-RNA) database in humans. (G) Schematic of hnRNPL binding to the PCMT1 3′ UTR and (H) hnRNPL association with cytosolic and nuclear PCMT1 mRNA in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs and anti-PCMT1-iTregs. Red frames indicate the expected amplicon size. Data represent the mean ± SEM of two or three independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test was used for analysis. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

PCMT1 has been implicated in multiple RNA processing functions, including regulating mRNA nuclear export to facilitate protein translation. We speculated that this is likely further mediated by its regulation of, or interaction with, RBPs. Among these, hnRNPL has been shown to be a key regulator of iTreg post-transcriptional regulation. To explore the possible link between PCMT1 and hnRNPL, we first asked whether anti-pPKCθ treatment affected hnRNPL expression. In anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, hnRNPL cytosolic expression was increased, while nuclear hnRNPL levels were diminished (Figure 4D). However, in anti-PKCθ-Tconvs, we observed decreased cytosolic and increased nuclear hnRNPL (Figures S5A and S5B). These results suggested to us that hnRNPL cellular localization not only contributes to iTreg differentiation, but that its cytosolic versus nuclear accumulation is regulated in a PKCθ-dependent manner.

Our in vitro data suggested that PKCθ and PCMT1 may act within the same signaling pathway to regulate FOXP3 and IFNγ expression. Therefore, we asked whether either of these pathways converge at the level of hnRNPL association. To determine whether PKCθ or PCMT1 physically interacts with hnRNPL, we immunoprecipitated cytosolic and nuclear hnRNPL and examined the degree of PKCθ- and PCMT1-hnRNPL interaction in iTregs treated either with anti-pPKCθ or with anti-PCMT1. We observed that, in DMSO-iTregs, hnRNPL and PKCθ interactions appear equivalent in the cytosol and the nucleus, while hnRNPL-PCMT1 interactions are reduced, but detectable in the cytosol, and are more robust in the nucleus (Figure 4E). Nuclear association of PKCθ or of PCMT1 with hnRNPL was significantly diminished in iTregs following either anti-pPKCθ or anti-PCMT1 treatment. Cytosolic hnRNPL-PKCθ association was significantly reduced in anti-pPKCθ-treated iTregs but increased in anti-PCMT-iTregs. We found the opposite trend for hnRNPL-PCMT1 interactions: cytosolic hnRNPL-PCMT1 binding increased in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs but was lower in anti-PCMT1-iTregs (Figure 4E). These data are consistent with a model whereby PKCθ and PCMT1 may interact with each other and compete for binding to hnRNPL, which may act to shuttle both proteins into the nucleus. Constraining either pPKCθ or PCMT1 via intracellular antibody delivery may allow increased cytosolic association of the other protein with hnRNPL (Figure 4E, upper two panels, left side). The fact that both PKCθ and PCMT1 are undetectable in nuclear extracts in anti-pPKCθ- and anti-PCMT1-iTregs supports the notion that these two proteins interact in the cytosol, and delivering an antibody to one protein effectively constrains nuclear translocation of both (Figure 4E, upper two panels, right side). We noted that hnRNPL is also diminished in nuclear extracts from anti-pPKCθ- and anti-PCMT1-iTregs, further suggesting that constraining pPKCθ or PCMT1 may also impede hnRNPL nuclear shuttling, when bound to either of these proteins in the cytosol (Figure 4E, third panel, right side). Altogether, these results confirmed that both PKCθ and PCMT1 interact with hnRNPL, and that the cellular compartment in which these interactions take place can be manipulated via anti-pPKCθ or anti-PCMT1 delivery into iTregs.

A major function of RBPs, such as hnRNPL, is to aid in mRNA export prior to translation. Given the reduced nuclear interactions of hnRNPL with PKCθ and PCMT1 following antibody delivery, we asked whether this also negatively affected the ability of hnRNPL to bind PCMT1 mRNA. Using several bioinformatics tools, including the Catalog of Inferred Sequence Binding Preferences of RNA binding proteins (CISBP-RNA) database, we identified two CA-rich RNA binding motifs recognized by hnRNPL (Figure 4F). CA-rich elements within 3′ UTR sequences serve as central hubs for further RNA processing events, influencing RNA stability and nuclear export.62 In general, incorrectly spliced mRNAs, such as those with retained introns or aberrant exon skipping, can undergo either nuclear RNA decay or nonsense-mediated RNA decay in the cytoplasm. Only correctly spliced, stable mRNAs are properly exported and translated.63 To investigate whether hnRNPL-PCMT1 or hnRNPL-PKCθ association is important for correctly spliced, stable mRNA export in iTregs, we isolated cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA from iTregs followed by RNA immunoprecipitation. We designed 3′ UTR-specific primers to amplify putative hnRNPL binding sites, including two putative hnRNPL binding sites within the 3′ UTR of PCMT1 (Figure 4G). We subsequently identified hnRNPL binding sites located within the 3′ UTR of all of the key iTreg genes studied herein, namely FOXP3, IFNG, IFNGR1, and PDCD1 (Figure S4). Strikingly, we found robust hnRNPL-PCMT1 mRNA association in the cytosol of DMSO-iTregs. These interactions were markedly reduced in iTregs treated either with anti-pPKCθ or with anti-PCMT1 and were accompanied by a concomitant increase in nuclear hnRNPL-PCMT1 association (Figure 4H). We detected hnRNPL-PDCD1 interactions, mainly in the nucleus, of DMSO-iTregs, while anti-PCMT1-treated iTregs showed slightly more hnRNPL-PDCD1 association in the cytosol (Figure S5C). Cytosolic hnRNPL-FOXP3 interactions remained intact in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs but were lost in anti-PCMT1-iTregs (Figure S5D). Nuclear export of stable IFNG and IFNGR1 mRNA was not appreciably affected by anti-pPKCθ or anti-PCMT1 delivery (Figures S5E and S5F). These results indicate that stable mRNA export of PCMT1 is tightly regulated by hnRNPL through its association with PCMT1 and PKCθ. More importantly, both PKCθ and PCMT1 can regulate selective mRNA export of key iTreg genes in a gene-specific manner.

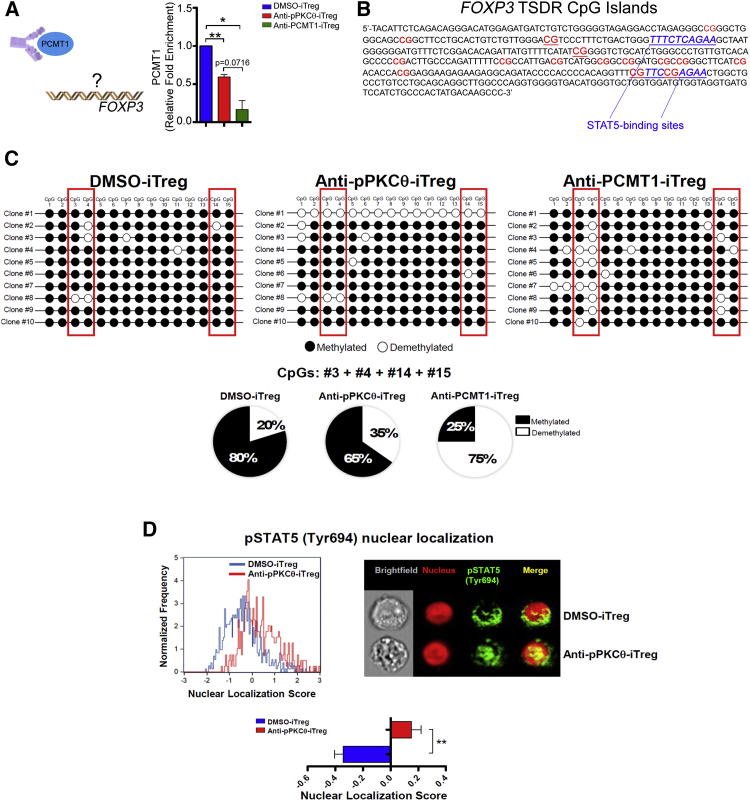

PCMT1 Acts to Destabilize the iTreg Phenotype through Its Effects on FOXP3 Methylation

In many aspects, delivering anti-PCMT1 into iTregs phenocopied the results we obtained when we generated anti-pPKCθ-iTregs. This included producing equivalent populations of FOXP3hi and IFNγhi iTregs. Therefore, we asked whether PCMT1 directly regulates FOXP3 gene expression. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), followed by qPCR, we determined that PCMT1 binds directly to FOXP3 in iTregs. Moreover, anti-pPKCθ and anti-PCMT1 treatment dramatically reduced PCMT1-FOXP3 interactions in iTregs (Figure 5A). These data suggest that fully functional PKCθ and PCMT1 are critical for PCMT1-FOXP3 association. FOXP3 expression is tightly regulated by several transcription factors that bind the TSDR, following its demethylation. To date, a highly demethylated TSDR is the most reliable marker for stable FOXP3 expression. In most iTregs, the TSDR is methylated, leading to destabilized FOXP3 expression.64,65 This instability is thought to result from reduced STAT5 binding within the TSDR.66,67 We identified 15 CpG islands within the human FOXP3 TSDR sequence, including two that flanked the proximal STAT5 binding site, and two that overlapped with the distal STAT5 binding site (Figure 5B). As a logical extension to our discovery that PCMT1, a methlytransferase, directly binds to FOXP3, we evaluated the level of TSDR methylation in DMSO-iTregs and compared it with that of anti-pPKCθ- and anti-PCMT1-treated iTregs, using bisulfite sequencing of 10 individual clones isolated from each of the three iTreg treatment conditions, as indicated (Figure 5C). When we assessed the methylation of the four specific CpGs flanking the STAT5 binding site, we observed that DMSO-iTregs showed the lowest percentage (20%) of demethylation of these CpGs in the clones analyzed. Interestingly, in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, approximately 35% of these CpG sites within the TSDR were demethylated. Following anti-PCMT1 treatment, however, we found that of the clones tested, 75% of CpG sites that either flanked or overlapped with STAT5 binding sites were demethylated (Figure 5C), strongly suggesting that inhibiting PCMT1 may enhance the stability of FOXP3 expression by reducing methylation of key CpG sites within the TSDR. We further speculated that increased demethylation of CpG islands surrounding the STAT5 binding sites would increase nuclear retention of pSTAT5. To examine this possibility, we used imaging flow cytometry to evaluate levels of nuclear pSTAT5 in DMSO- and anti-pPKCθ-iTregs in vitro. Consistent with our prediction, anti-pPKCθ-iTregs exhibited significantly greater amounts of nuclear pSTAT5, compared to iTregs differentiated in the presence of DMSO (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

PCMT1 Acts to Destabilize the iTreg Phenotype through Its Effects on FOXP3 Methylation

(A) Chromatin immunoprecipitation quantifying PCMT1 occupancy on the FOXP3 promoter in iTregs. (B) CpG islands (indicated in bold type) and STAT5-binding sites (underlined in blue) in the human FOXP3 TSDR. (C) Bisulfite sequencing of 10 different clones per iTreg treatment showing FOXP3 TSDR CpG islands. Percentages of CpGs demethylated at sites #3, #4, #14, and #15 were quantified and are shown as pie charts. (D) Nuclear localization of pSTAT5 (Tyr694) was quantified by imaging flow cytometry using Amnis ImageStream analysis. Representative cell frequency histograms, along with representative images at ×60 magnification, show anti-pPKCθ-iTregs with nuclear pSTAT5. The Amnis IDEAS wizard, with nuclear masking applied, was used to quantify nuclear localization of pSTAT5, based on similarity score. Data represent mean ± SEM of two or three independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test was used for analysis. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

Overall, we provide strong evidence that PKCθ negatively regulates iTreg induction through its modulation of two key components of RNA processing, PCMT1 and hnRNPL, via multiple cellular mechanisms. Furthermore, our data suggest that this inhibitory pathway can be interrupted in iTregs through the intracellular delivery either of anti-pPKCθ or anti-PCMT1, to modulate these mechanisms in favor of enhancing iTreg suppressive functions. Finally, we identified, for the first time, that the protein repair methyltransferase, PCMT1, acts as a key iTreg instability factor through its control of FOXP3 TSDR methylation.

Discussion

A great deal has been learned about transcriptional regulation of immune cell responses. A growing area of interest focuses on alternative splicing and RNA processing in regulating T cell differentiation and function following antigenic stimulation, as distinct protein isoforms for many T cell genes have been identified.19,22,68, 69, 70 These processes operate together with RBPs, transcription factors, and epigenetic modifiers.6,69 Although numerous immune-related genes undergo alternative splicing and RNA processing, differential isoform expression and RNA processing in Treg differentiation remain largely unexplored.

Our studies provide an extensive analysis of altered RNA processing in the context of iTreg differentiation and function, and we utilized several approaches to investigate PKCθ modulation of splicing regulators, RNA splicing, stability, and nuclear export. We specifically targeted pPKCθ, using a cell-penetrating antibody, to probe post-transcriptional RNA processing in iTregs. We discovered that PKCθ influenced RNA processing of several iTreg genes, including CD45 (PTPRC), FOXP3, PDCD1, IFNG, and IFNGR1, in cell-specific and tissue-specific contexts. Furthermore, splicing regulator analysis revealed that two RNA regulatory proteins, hnRNPL and PCMT1, were controlled by PKCθ at multiple levels. We found that PKCθ regulated both the subcellular localization of hnRNPL and its binding to mRNA. Additionally, we showed that PKCθ regulated PCMT1 alternative splicing, stabilized PCMT1 mRNA through its association with hnRNPL, and enhanced its nuclear export prior to its translation into stable protein. However, anti-pPKCθ delivery into iTregs altered the PCMT1 splicing pattern and destabilized and prevented the nuclear export of PCMT1 mRNA, due to loss of PCMT1-hnRNPL binding. Utilizing our cell-penetrating peptide-intracellular antibody delivery strategy to target PCMT1, we identified a practical approach to promote iTreg differentiation and function. We determined that PCMT1 directly binds to the FOXP3 promoter and, more interestingly, inhibiting PCMT1 increased FOXP3 TSDR demethylation, thereby enhancing FOXP3 stability and iTreg maintenance. In conjunction with our recent discovery that intracellular anti-pPKCθ delivery generates a unique, highly suppressive population of FOXP3hiPD1hiIFNγhi iTregs,39 this study supports the notion that PKCθ negatively regulates iTreg differentiation and stability by modulating key RNA processing regulators.

We observed elevated pSTAT1 (Y701) levels in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, compared to DMSO-iTregs. Reduced pAKT, coupled with upregulated pSTAT1, has previously been associated with enhanced IFNγ production by CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs in mice. Moreover, AKT and STAT1 were found to function within the same pathway, with both induced by IFNγ, and served to control skin graft rejection in vivo.60,61 IFNγ produced by these Tregs also induced indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) production by antigen-presenting cells, to further suppress immune cell activity.71 Anti-pPKCθ-iTregs exhibited higher IFNγ expression and greater suppressive capacity, both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that this pathway may critically contribute to the suppressive function of iTregs through autonomous IFNγ signaling. Anti-pPKCθ-iTregs also express high levels of PD1, which may also be related to this pathway. A downstream phosphatase of PD1 signaling, SHP-2, was shown to interact with cytosolic STAT1, reducing its recruitment to the IFNγ receptor (IFNγR), and dampening Th1 function.72 Further studies investigating how PD1 and IFNγ signaling pathways might intersect downstream of PKCθ modulation in iTregs are needed to fully elucidate cellular mechanisms that regulate suppressive function and Th1-Treg plasticity.

Members of the PKC family can influence mRNA splicing in various cell types and have been shown to phosphorylate SC35, which functions in co-transcriptional regulation of alternative splicing.19,40,70 As previously indicated, we found that PKCθ regulated cytoplasmic versus nuclear distribution of splicing regulators. Among these, we focused on hnRNPL, as it was uniquely altered in iTregs following PKCθ inhibition. Unlike other splicing regulators we investigated, only hnRNPL was sequestered in the cytosol after anti-pPKCθ delivery. This correlated with increased exon skipping of CD45 (PTPRC), as well as greater expression of CD45RO, which is consistent with reduced levels of nuclear hnRNPL in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, compared to DMSO-iTregs. Alternatively, we saw no differences in the splicing patterns of FOXP3, PDCD1, IFNG, and IFNGR1 in iTregs, regardless of treatment, suggesting that these genes may not be alternatively spliced during in vitro differentiation. We did observe shorter 3′ UTR lengths in PDCD1, indicating that anti-pPKCθ-iTregs implement gene-specific 3′ UTR processing, which may further stabilize PD1 expression in vitro. Similar mechanisms may account for the in vivo RNA dynamics we observed, in the context of immune response and Treg differentiation. Anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, which exhibited elevated PD1 expression and superior suppressive function, were long-lasting and accumulated in high numbers in the BM and spleen of mice following adoptive iTreg transfer in a humanized mouse model of GvHD.39 Studies have reported that Tregs can lose FOXP3 expression and take on a proinflammatory phenotype in several disease environments.73 However, we determined that only anti-pPKCθ-iTregs maintained their FOXP3 expression in the BM, since we were unable to amplify stable mRNA in DMSO-iTregs. Of note, we detected tissue-specific changes in the alternative splicing patterns of FOXP3, PDCD1, IFNG, and IFNGR1 in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs. Moreover, only in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs recovered from the BM could we detect stable mRNA production. A host of immune cells are available to act differentially on iTregs in vivo through direct and indirect mechanisms. Thus, one potential explanation for the differences in alternative splicing patterns we observed in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs in vitro and in vivo may be attributed to the interactions of iTregs with other cell types. Additional studies are needed to identify these in vivo modulators.

Most strikingly, our data reveal an as-yet-undescribed contribution of the protein methyltransferase PCMT1 to FOXP3 methylation, and which we demonstrate is regulated by PKCθ signaling. We showed that PCMT1 expression was downregulated following anti-pPKCθ delivery. Additionally, in anti-pPKCθ-iTregs, we observed phosphorylated PCMT1 in the nucleus, suggesting that post-translational control of PCMT1 is modulated downstream of PKCθ signaling. In the brain, PCMT1 reportedly regulates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, as increased AKT/GSK3β signaling is seen in the hippocampus of Pcmt1 knockout mice.74,75 Additionally, GSK3β phosphorylation at serine 9, which inhibits GSK3β function, was low in Pcmt1+/+ mice, indicating an abundance of activated GSK3β, and this suggests that Pcmt1 and GSK3β may function in a positive feedback loop.76 Considering that PKCθ and GSK3β work in opposition, it is interesting to speculate that GSK3β may phosphorylate PCMT1 to regulate its function when PKCθ activity is inhibited in iTregs. Furthermore, the AKT/GSK3β pathway is a critical signaling axis in iTreg differentiation, since inhibiting mTOR promotes Treg induction.77 Collectively, these studies suggest that inhibiting PCMT1 could promote Treg induction, in agreement with the data we present in this report; however, additional studies are needed to identify the upstream kinases responsible for phosphorylating PCMT1.

Our results also indicate that PKCθ can regulate PCMT1 post-transcriptionally. Anti-pPKCθ-iTregs displayed distinct PCMT1 splicing patterns and less stable mRNA in vitro. Furthermore, and consistent with our in vitro data, we observed a tissue- and cell-specific switch in PCMT1 RNA processing in vivo as well. Based on these robust post-translational and post-transcriptional modifications to PCMT1, downstream of PKCθ signaling, we delivered anti-PCMT1 to iTregs to further investigate PCMT1 functions in iTreg differentiation. As we predicted, anti-PCMT1 delivery also generated a higher percentage of iTregs, which showed high FOXP3 and IFNγ expression in vitro. Moreover, we found that PCMT1 also interacted with hnRNPL. Both anti-pPKCθ and anti-PCMT1 delivery reduced the interaction of these respective proteins with hnRNPL in the nucleus and resulted in an inverse association of these hnRNPL-interacting proteins in the cytosol: hnRNPL-PKCθ binding was diminished in the cytosol, while hnRNPL-PCMT1 interactions increased following anti-pPKCθ delivery. Conversely, in anti-PCMT1-treated iTregs, cytosolic hnRNPL-PKCθ binding increased, while hnRNPL-PCMT1 interactions were attenuated. Previous reports suggested that PCMT1 is part of an RNA nuclear export complex and can associate with multiple RBPs.58 Considering PCMT1-hnRNPL interactions in the context of RNA export, we found that PKCθ regulates hnRNPL-RNA interactions in iTregs. Interestingly, inhibiting PKCθ or PCMT1 abrogated stable PCMT1 mRNA export to the cytoplasm, likely due to loss of hnRNPL-PCMT1 binding, and suggests that PCMT1 may also regulate its own mRNA export. Finally, we observed that PKCθ and PCMT1 selectively regulated mRNA export and hnRNPL interactions with FOXP3, PDCD1, IFNG, and IFNGR1 mRNA. It remains to be determined whether anti-pPKCθ and anti-PCMT1 delivery differentially influence translational control of these mRNAs in the cytosol of iTregs.

Our parallel findings in anti-pPKCθ- and anti-PCMT1-iTregs also revealed the possibility that more stable iTregs resulted from epigenetic modification of FOXP3, together with unique expression of IFNγ. Currently, the most reliable marker for determining Treg stability is the methylation status of the FOXP3 TSDR.78 Other reports indicate that IFNγ-expressing Tregs exhibited a more stable Treg phenotype, and this was associated with a more highly demethylated TSDR.79 Intriguingly, we observed direct binding of PCMT1 to FOXP3 in iTregs, and this binding could be prevented by intracellular delivery either of anti-pPKCθ or anti-PCMT1. PCMT1 contains a domain with global methyltransferase activity, and we further analyzed the methylation status of the FOXP3 TSDR in anti-PCMT1-treated iTregs. Strikingly, we observed significantly lower TSDR methylation in anti-PCMT1-treated iTregs, and, more importantly, demethylated CpGs overlapped with the STAT5 binding site, consistent with a requirement for STAT5 binding for the maintenance of FOXP3 gene expression. A deeper analysis of the TSDR methylation pattern in anti-PCMT1-treated iTregs revealed that the fourth CpG island showed consistently high demethylation. We followed up this observation by running the PROMO algorithm to identify putative transcription factor binding sites surrounding this CpG. We were intrigued to find that the GATA-1 transcription factor binding site spans this demethylated CpG, in close proximity to XBP1, TFIID, and RXR-α binding sites.80,81 GATA-1 is considered a “Treg phenotype-locking” transcription factor able to enhance transcriptional activity of FOXP3.82,83 Hence, our results reinforce the idea that targeting PCMT may be a beneficial strategy for maximizing iTreg stability and suppressive function.

Collectively, our data reveal that the T cell-specific kinase PKCθ and the protein methyltransferase PCMT1 are intimately involved in controlling iTreg differentiation, stability, and function in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, using synthetic CPPMs we could deliver functional antibodies across the cell membrane of human CD4 T cells, which allowed us to define and manipulate in vitro the cellular mechanisms that regulate iTreg differentiation. This approach shows great promise as a tool for probing intracellular signaling pathways, as well as for manipulating human immune cells ex vivo, in the context of advancing cell-based therapies.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal studies were approved by, and conducted under the oversight of, the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Seven-week old female NSG mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice were rested for 1 week prior to use, housed under pathogen-free conditions in micro-isolator cages, and received acidified water (pH 3.0) supplemented with antibiotics (trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole) throughout the duration of the experimental procedures.

Antibodies and Reagents

Immunoblotting antibodies used in this study were as follows: anti-mouse pSC35 (clone SC35; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-mouse hnRNPL (clone 4D11; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), anti-rabbit PCMT1 (polyclonal; LifeSpan Biosciences, Seattle, WA), anti-mouse pSTAT1 (Y701; clone KIKSI0803; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), anti-mouse STAT1 (clone 10C4B40; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-rabbit pAKT (S473; polyclonal), anti-rabbit AKT (polyclonal), anti-mouse histone H3 (clone 96C10; all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and anti-mouse α-tubulin (clone B-5-1-2; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Flow cytometry antibodies used in this study were anti-CD4 (Brilliant Violet 711 [BV711]; clone RPA-T4), anti-CD25 (phycoerythrin [PE]-Cy7; clone BC96), anti-CD127 (Alexa Fluor 700 [AF700]; clone A019D5), anti-FOXP3 (Alexa Fluor 488 [AF488]; clone 150D; all from BioLegend), anti-IFNγ (allophycocyanin [APC]; clone B27; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), anti-rabbit PCMT1 (unconjugated, polyclonal; LifeSpan Biosciences), and F(ab′)2-goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (Qdot 625; polyclonal; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Live/dead staining was performed utilizing a Zombie Aqua fixable viability kit (BioLegend).

Human iTreg Differentiation following Intracellular Anti-pPKCθ or Anti-PCMT1 Delivery

1 μM synthetic CPPM and 25 nM anti-pPKCθ (Thr538, clone F4H4L1; Life Technologies) or 1 μM P13D5 and 25 nM anti-PCMT1 (polyclonal; LifeSpan Biosciences) were complexed in PBS (phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2) at a specific ratio (CPPM/antibody of 40:1). The CPPM/antibody complex was incubated for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Meanwhile, CD4 T cells were isolated from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (purchased from STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) using the MojoSort human T cell isolation kit (BioLegend). Isolated human CD4 T cells were then treated with the CPPM/antibody complex for 4 h at 37°C (some cells were treated with DMSO as vehicle control). Cells were harvested and washed with PBS. Cells were thoroughly washed twice with 20 U/mL heparin in PBS for 5 min on ice to remove residual complexes bound to the exterior of the cell membrane. For iTreg differentiation, a CellXVivo human Treg differentiation kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used and iTreg differentiation medium was prepared using X-VIVO 15 chemically defined, serum-free hematopoietic cell medium according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Treated cell pellets were resuspended in iTreg differentiation media (concentration) and seeded into wells of a 12-well tissue culture plate precoated with 5 μg/mL anti-CD3ε plus 2.5 μg/mL anti-CD28 and stimulated for 5 days at 37°C.

Immunoblotting

iTregs were harvested on day 5 of differentiation. Nuclear and cytosolic extracts were prepared by using an NE-PER nuclear and cytosolic extraction kit (Thermo Scientific). 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) Laemmli buffer was added into the samples for running on 8% SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting. The blots were probed for RBPs for further analysis. Anti-α-tubulin was probed as a cytosolic lysate loading control, and anti-histone H3 was probed as a nuclear lysate loading control.

In Vivo RNA Analysis of iTregs in a Humanized GvHD Model

Total CD4 T cells were isolated from human PBMCs (hPBMCs) collected from a healthy donor, treated with a CPPM/anti-pPKCθ complex, and then differentiated for 5 days into iTregs, as previously described. On day 4, total hPBMCs from the same donor were thawed and rested overnight in fresh RPMI 1640 complete media (10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM l-glutamine) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. On day 5, NSG mice were conditioned with 2 Gy of total body irradiation using a 137Cs source and then rested for 4–6 h. 10 × 106 total hPBMCs were mixed with 3.3 × 106 iTregs and adoptively transferred into irradiated NSG mice via the tail vein. Body weight and disease symptoms were observed daily. On day 17, some animals were sacrificed for tissue analysis. BM cells, recovered from the tibias and femurs, and splenocytes were isolated by manipulation through a 40-μm filter. Red blood cells were lysed in ACK lysis buffer, and the remaining white blood cells were enumerated using trypan blue exclusion. Afterward, cells were incubated with human CD4 T lymphocyte enrichment cocktail (BD Biosciences) followed by incubation with BD IMag streptavidin particles plus (BD Biosciences) to deplete non-CD4 T cell fractions. CD4 T cells were sequentially incubated with biotinylated anti-CD127 antibody followed by incubation with BD IMag streptavidin particles plus. The CD127− fraction was collected and further incubated with biotinylated anti-CD25 antibody followed by incubation with BD IMag streptavidin particles plus to obtain the CD25+ iTreg fraction. The naive CD127+CD25− T cell fraction was also recovered. Total RNA was isolated as described below.

qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using the Quick-RNA isolation kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using 2′-deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphates (dNTPs) (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) reverse transcription buffer (New England Biolabs), oligo(dT) (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), RNase inhibitor (Promega), and M-MuLV reverse transcription (New England Biolabs) on a Mastercycler gradient thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Primers used for PCMT amplification were forward primer (5′-GCTGAAGAAGCCCCTTATGA-3′) and reverse primer (5′- TCTTCCTCCGGGCTTTAACT-3′). qPCR was performed in duplicate with 2× SYBR Green qPCR master mix (BioTool, Ely, UK) using the Mx3000P system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). qPCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 1 min, 95°C for 25 s, 62°C for 25 s (40 cycles), 95°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min, and 95°C for 30 s. Relative gene expression was determined using the ΔΔCt method. The results are presented as the fold expression of the gene of interest normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin (ACTB) for cells and relative to the Tconv + DMSO sample for in vitro experiments and naive + DMSO for in vivo experiments.

RT-PCR for Splicing and 3′ UTR Analyses

Total RNA was isolated using the Quick-RNA isolation kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 0.5 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using random hexamers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) with M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs) on a Mastercycler gradient thermal cycler (Eppendorf). Splicing primers (Table S1) and 3′ UTR primers (Table S2) were specifically designed for the genes analyzed in this study. PCR (35 cycles) was performed using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) followed by resolution on 2% agarose gel. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 98°C for 30 s, annealing at 98°C for 5 s, 52°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Amplicons were imaged using the G:BOX gel documentation system (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA).

λ-Phosphatase Treatment

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 0.5% sodium deoxycholate). Lysates were treated with 100 U of λ protein phosphatase (New England Biolabs) in the presence of 1 mM MnCl2 for 1 h at 30°C. 1× SDS Laemmli buffer was added into the samples and they were boiled for 5 min at 95°C. The samples were run on 8% SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting.

hnRNPL Immunoprecipitation

iTregs were harvested after 5 days of differentiation and lysed in immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 250 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40], protease + phosphatase inhibitors). DynaBeads (protein G) were coupled with 3 μg of anti-hnRNPL (4D11; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) in the presence of 1% BSA in PBS and incubated for 2 h at 4°C with rotation. After the incubation, the antibody-coupled DynaBeads were washed six times with 1 mL of immunoprecipitation wash buffer (Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 200 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40). Later, cell lysates were incubated with antibody-coupled DynaBeads for 1 h at 4°C using a rotator. Subsequently, beads were washed six times with 0.5 mL of immunoprecipitation wash buffer. 1× SDS Laemmli buffer was added into the samples, and lysates were run on an 8% SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-hnRNPL, anti-PKCθ, and anti-PCMT1.

RNA Immunoprecipitation

After harvesting on day 5 of differentiation, cells were lysed in RNA immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 250 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1× protease + phosphatase inhibitors, 100 U/mL RNase inhibitor). DynaBeads (protein G) were coupled with 3 μg of anti-hnRNPL (4D11; Novus Biologicals) or anti-IgG (control antibody) in the presence of 1% BSA in PBS and incubated for 2 h at 4°C with rotation. After the incubation, the antibody-coupled DynaBeads were washed six times with 1 mL of immunoprecipitation wash buffer (Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 200 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40). Cell lysates were incubated with antibody-coupled DynaBeads for 1 h at 4°C using a rotator. Subsequently, beads were washed six times with 0.5 mL of immunoprecipitation wash buffer + 100 U/mL RNase inhibitor. RNA was purified via a Quick-RNA isolation kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol to further use on RT-PCR experiments.

ChIP-qPCR

Cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde, lysed in SDS lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, and 50 mM Tris [pH 8.1]), and sonicated with a Bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode, Denville, NJ, USA). Cell lysates were incubated with 2 mg of anti-PCMT1 (LifeSpan Biosciences, polyclonal) or normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) coupled to DynaBeads at 4°C for 2 h. Protein-DNA complexes were recovered with DynaBeads, washed, eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3), and reverse crosslinked overnight at 65°C. DNA was purified by proteinase K digestion and extracted with phenol-chloroform extraction. Aqueous phase was transferred into a fresh tube and the DNA was precipitated with 3 M sodium acetate containing 2 mL of glycogen and 4 vol of ethanol by keeping overnight at −20°C. Genes were amplified using qPCR primers designed as follows: human FOXP3, forward (5′-TGACCAAGGCTTCATCTGTG-3′), reverse (5′-GAGGAACTCTGGGAATGTGC-3′); and human IFNG, forward (5′-CTCTTGGCTGTTACTGCCAGG-3′), reverse (5′-CTCCACACTCTTTTGGATGCT-3′). qPCR was performed in duplicate with 2× SYBR Green qPCR master mix (BioTool) using the Mx3000P system (Agilent Technologies). qPCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 1 min, 95°C for 25 s, 62°C for 25 s (40 cycles), 95°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min, and 95°C for 30 s. Relative gene expression was determined using the ΔΔCt method. The results are presented as the fold expression of the gene of interest normalized to the housekeeping gene ACTB for cells and relative to the Tconv + DMSO sample.

Bioinformatics for RBP Motifs

Splice variants, intron-exon sequences, and 3′ UTR sequences were analyzed and obtained from Ensembl. RBP motifs for hnRNPL were analyzed utilizing the CISBP-RNA database.84 3′ UTR sequences were analyzed for hnRNPL-binding sites using RBPmap.85

Bisulfite Sequencing

Sodium bisulfite modification of genomic DNA was carried out using the EZ DNA Methylation-Direct kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Bisulfite-treated DNA was PCR amplified using the following methylation-specific primers and ZymoTaq DNA polymerase (Zymo Research): forward primer, 5′-TGTTTGGGGGTAGAGGATTT-3′, reverse primer, 5′-TATCACCCCACCTAAACCAA-3′. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s + annealing at 55°C for 40 s + extension at 72°C for 1 min, and final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Amplified DNA products were gel purified using a GeneJET gel extraction kit (Thermo Scientific) and cloned into pMiniT 2.0 cloning vector using the NEB PCR cloning kit (New England Biolabs). Competent cells were transformed with the vector. Ten individual positive bacterial colonies were selected, from which recombinant plasmid DNA was purified and sequenced with Sanger sequencing (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ, USA).

Statistical Analysis

The results shown are the mean ± SEM. All in vitro experimental replicates were repeated at least three times. All in vivo experimental replicates were repeated in three separate experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test using Prism 5 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical comparison of two groups, with Welch’s correction applied when variances were significantly different. Survival benefit was determined using Kaplan-Meier analysis with an applied log rank test. p values of ≤0.05 were considered significantly different.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: E.I.O. and L.M.M.; Methodology: E.I.O., S.S., and L.M.M.; Investigations: E.I.O., S.S., and J.A.T.; Writing – Original Draft: E.I.O. and L.M.M.; Writing – Review & Editing: E.I.O., B.A.O., and L.M.M.; Project Administration: G.N.T. and L.M.M.; Funding Acquisition: B.A.O. and L.M.M.; Supervision: B.A.O., G.N.T., and L.M.M.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A.S. Burnside, Director of the Flow Cytometry Core Facility, Institute for Applied Life Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, for guidance, C. Marcho for providing critical help with bisulfite sequencing analysis, and R.A. Goldsby for critical assessment of the manuscript. This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH 5P01CA16600 to B.A.O.) and the Department of Defense (W81XWH1910540 to L.M.M.).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.06.012.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Kafasla P., Skliris A., Kontoyiannis D.L. Post-transcriptional coordination of immunological responses by RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:492–502. doi: 10.1038/ni.2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black D.L. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matlin A.J., Clark F., Smith C.W.J. Understanding alternative splicing: towards a cellular code. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:386–398. doi: 10.1038/nrm1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornblihtt A.R., Schor I.E., Alló M., Dujardin G., Petrillo E., Muñoz M.J. Alternative splicing: a pivotal step between eukaryotic transcription and translation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:153–165. doi: 10.1038/nrm3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melton A.A., Jackson J., Wang J., Lynch K.W. Combinatorial control of signal-induced exon repression by hnRNP L and PSF. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:6972–6984. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00419-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ip J.Y., Tong A., Pan Q., Topp J.D., Blencowe B.J., Lynch K.W. Global analysis of alternative splicing during T-cell activation. RNA. 2007;13:563–572. doi: 10.1261/rna.457207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keene J.D. RNA regulons: coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han S.P., Tang Y.H., Smith R. Functional diversity of the hnRNPs: past, present and perspectives. Biochem. J. 2010;430:379–392. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allemand E., Guil S., Myers M., Moscat J., Cáceres J.F., Krainer A.R. Regulation of heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 transport by phosphorylation in cells stressed by osmotic shock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3605–3610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409889102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaustein M., Pelisch F., Tanos T., Muñoz M.J., Wengier D., Quadrana L., Sanford J.R., Muschietti J.P., Kornblihtt A.R., Cáceres J.F. Concerted regulation of nuclear and cytoplasmic activities of SR proteins by AKT. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:1037–1044. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel N.A., Kaneko S., Apostolatos H.S., Bae S.S., Watson J.E., Davidowitz K., Chappell D.S., Birnbaum M.J., Cheng J.Q., Cooper D.R. Molecular and genetic studies imply Akt-mediated signaling promotes protein kinase CβII alternative splicing via phosphorylation of serine/arginine-rich splicing factor SRp40. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:14302–14309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Houven van Oordt W., Diaz-Meco M.T., Lozano J., Krainer A.R., Moscat J., Cáceres J.F. The MKK(3/6)-p38-signaling cascade alters the subcellular distribution of hnRNP A1 and modulates alternative splicing regulation. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:307–316. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganguly K., Giddaluru J., August A., Khan N. Post-transcriptional regulation of immunological responses through riboclustering. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:161. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meininger I., Griesbach R.A., Hu D., Gehring T., Seeholzer T., Bertossi A., Kranich J., Oeckinghaus A., Eitelhuber A.C., Greczmiel U. Alternative splicing of MALT1 controls signalling and activation of CD4+ T cells. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11292. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uehata T., Iwasaki H., Vandenbon A., Matsushita K., Hernandez-Cuellar E., Kuniyoshi K., Satoh T., Mino T., Suzuki Y., Standley D.M. Malt1-induced cleavage of regnase-1 in CD4+ helper T cells regulates immune activation. Cell. 2013;153:1036–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabowski P.J. Splicing regulation in neurons: tinkering with cell-specific control. Cell. 1998;92:709–712. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Screaton G.R., Xu X.N., Olsen A.L., Cowper A.E., Tan R., McMichael A.J., Bell J.I. LARD: a new lymphoid-specific death domain containing receptor regulated by alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:4615–4619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J., Shen L., Najafi H., Kolberg J., Matschinsky F.M., Urdea M., German M. Regulation of insulin preRNA splicing by glucose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:4360–4365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch K.W., Weiss A. A model system for activation-induced alternative splicing of CD45 pre-mRNA in T cells implicates protein kinase C and Ras. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:70–80. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.70-80.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heyd F., Lynch K.W. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of PSF by GSK3 controls CD45 alternative splicing. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oberdoerffer S., Moita L.F., Neems D., Freitas R.P., Hacohen N., Rao A. Regulation of CD45 alternative splicing by heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein, hnRNPLL. Science. 2008;321:686–691. doi: 10.1126/science.1157610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch K.W. Consequences of regulated pre-mRNA splicing in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:931–940. doi: 10.1038/nri1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothrock C., Cannon B., Hahm B., Lynch K.W. A conserved signal-responsive sequence mediates activation-induced alternative splicing of CD45. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00434-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preussner M., Schreiner S., Hung L.H., Porstner M., Jäck H.M., Benes V., Rätsch G., Bindereif A. HnRNP L and L-like cooperate in multiple-exon regulation of CD45 alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5666–5678. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui J., Stangl K., Lane W.S., Bindereif A. HnRNP L stimulates splicing of the eNOS gene by binding to variable-length CA repeats. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:33–37. doi: 10.1038/nsb875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hui J., Reither G., Bindereif A. Novel functional role of CA repeats and hnRNP L in RNA stability. RNA. 2003;9:931–936. doi: 10.1261/rna.5660803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossbach O., Hung L.-H., Schreiner S., Grishina I., Heiner M., Hui J., Bindereif A. Auto- and cross-regulation of the hnRNP L proteins by alternative splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:1442–1451. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01689-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaudreau M.-C., Grapton D., Helness A., Vadnais C., Fraszczak J., Shooshtarizadeh P., Wilhelm B., Robert F., Heyd F., Möröy T. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L is required for the survival and functional integrity of murine hematopoietic stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:27379. doi: 10.1038/srep27379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothrock C.R., House A.E., Lynch K.W. HnRNP L represses exon splicing via a regulated exonic splicing silencer. EMBO J. 2005;24:2792–2802. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaudreau M.-C., Heyd F., Bastien R., Wilhelm B., Möröy T. Alternative splicing controlled by heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L regulates development, proliferation, and migration of thymic pre-T cells. J. Immunol. 2012;188:5377–5388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vu N.T., Park M.A., Shultz J.C., Goehe R.W., Hoeferlin L.A., Shultz M.D., Smith S.A., Lynch K.W., Chalfant C.E. hnRNP U enhances caspase-9 splicing and is modulated by AKT-dependent phosphorylation of hnRNP L. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:8575–8584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.443333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Booth N.J., McQuaid A.J., Sobande T., Kissane S., Agius E., Jackson S.E., Salmon M., Falciani F., Yong K., Rustin M.H. Different proliferative potential and migratory characteristics of human CD4+ regulatory T cells that express either CD45RA or CD45RO. J. Immunol. 2010;184:4317–4326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawse W.F., Boggess W.C., Morel P.A. TCR signal strength regulates Akt substrate specificity to induce alternate murine Th and T regulatory cell differentiation programs. J. Immunol. 2017;199:589–597. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vignali D.A.A., Collison L.W., Workman C.J. How regulatory T cells work. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudensky A.Y. Regulatory T cells and Foxp3. Immunol. Rev. 2011;241:260–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gavin M.A., Torgerson T.R., Houston E., DeRoos P., Ho W.Y., Stray-Pedersen A., Ocheltree E.L., Greenberg P.D., Ochs H.D., Rudensky A.Y. Single-cell analysis of normal and FOXP3-mutant human T cells: FOXP3 expression without regulatory T cell development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:6659–6664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509484103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polansky J.K., Kretschmer K., Freyer J., Floess S., Garbe A., Baron U., Olek S., Hamann A., von Boehmer H., Huehn J. DNA methylation controls Foxp3 gene expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38:1654–1663. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lal G., Bromberg J.S. Epigenetic mechanisms of regulation of Foxp3 expression. Blood. 2009;114:3727–3735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozay E.I., Shanthalingam S., Sherman H.L., Torres J.A., Osborne B.A., Tew G.N. Cell-Penetrating Anti-Protein Kinase C Theta Antibodies Act Intracellularly to Generate Stable, Highly Suppressive Regulatory T Cells. Mol. Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.05.020. Published online May 23, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCuaig R.D., Dunn J., Li J., Masch A., Knaute T., Schutkowski M., Zerweck J., Rao S. PKC-theta is a novel SC35 splicing factor regulator in response to T cell activation. Front. Immunol. 2015;6:562. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabellini G., Bortul R., Santi S., Riccio M., Baldini G., Cappellini A., Billi A.M., Berezney R., Ruggeri A., Cocco L., Martelli A.M. Diacylglycerol kinase-θ is localized in the speckle domains of the nucleus. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;287:143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boronenkov I.V., Loijens J.C., Umeda M., Anderson R.A. Phosphoinositide signaling pathways in nuclei are associated with nuclear speckles containing pre-mRNA processing factors. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:3547–3560. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qian W., Liang H., Shi J., Jin N., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Gong C.X., Liu F. Regulation of the alternative splicing of tau exon 10 by SC35 and Dyrk1A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6161–6171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin S., Coutinho-Mansfield G., Wang D., Pandit S., Fu X.-D. The splicing factor SC35 has an active role in transcriptional elongation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:819–826. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhong X.-Y., Wang P., Han J., Rosenfeld M.G., Fu X.-D. SR proteins in vertical integration of gene expression from transcription to RNA processing to translation. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kavanagh S.J., Schulz T.C., Davey P., Claudianos C., Russell C., Rathjen P.D. A family of RS domain proteins with novel subcellular localization and trafficking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1309–1322. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graveley B.R., Maniatis T. Arginine/serine-rich domains of SR proteins can function as activators of pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:765–771. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edmond V., Moysan E., Khochbin S., Matthias P., Brambilla C., Brambilla E., Gazzeri S., Eymin B. Acetylation and phosphorylation of SRSF2 control cell fate decision in response to cisplatin. EMBO J. 2011;30:510–523. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bin Dhuban K., d’Hennezel E., Nagai Y., Xiao Y., Shao S., Istomine R., Alvarez F., Ben-Shoshan M., Ochs H., Mazer B. Suppression by human FOXP3+ regulatory T cells requires FOXP3-TIP60 interactions. Sci. Immunol. 2017;2:eaai9297. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aai9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozay E.I., Gonzalez-Perez G., Torres J.A., Vijayaraghavan J., Lawlor R., Sherman H.L. Intracellular Delivery of Anti-PKCΘ (Thr538) via Protein Transduction Domain Mimics for Immunomodulation. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:2118–2130. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gruber A.R., Martin G., Keller W., Zavolan M. Means to an end: mechanisms of alternative polyadenylation of messenger RNA precursors. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2014;5:183–196. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nielsen C., Ohm-Laursen L., Barington T., Husby S., Lillevang S.T. Alternative splice variants of the human PD-1 gene. Cell. Immunol. 2005;235:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ryder L.R., Woetmann A., Madsen H.O., Ødum N., Ryder L.P., Bliddal H., Danneskiold-Samsøe B., Ribel-Madsen S., Bartels E.M. Expression of full-length and splice forms of FoxP3 in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2010;39:279–286. doi: 10.3109/03009740903555374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith E.L., Finney H.M., Nesbitt A.M., Ramsdell F., Robinson M.K. Splice variants of human FOXP3 are functional inhibitors of human CD4+ T-cell activation. Immunology. 2006;119:203–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Misra P., Qi C., Yu S., Shah S.H., Cao W.-Q., Rao M.S., Thimmapaya B., Zhu Y., Reddy J.K. Interaction of PIMT with transcriptional coactivators CBP, p300, and PBP differential role in transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:20011–20019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]