Abstract

3CLpro is the main protease of the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) responsible for their intracellular duplication. Based on virtual screening technology and molecular dynamics simulation, we found 23 approved clinical drugs such as Viomycin, Capastat, Carfilzomib and Saquinavir, which showed high affinity with the 3CLpro active sites. These findings showed that there were potential drugs that inhibit SARS-Cov-2's 3CLpro in the current clinical drug library, and these drugs can be further tested or chemically modified for the treatment of COVID-19.

Communicated by Ramaswamy H. Sarma

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, 3CLpro, approved drugs, virtual screening, molecular dynamics

1. Introduction

A novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has been identified as the pathogen of the coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19). As of 29 June 2020, more than 10 million patients worldwide have been diagnosed with COVID-19, and outbreaks have occurred in more than 195 countries. The coronavirus has spread globally because of its characteristics of strong contagion and high concealment, but there is no effective and specific antiviral therapy up to now. Currently, clinical treatments are suggested with known drugs such as Remdesivir and Chloroquine (Colson et al., 2020; Touret & de Lamballerie, 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Lopinavir and ritonavir used to treat HIV infection showed anti-CoV effect in vitro and are being tried for clinical treatment of COVID-19 (Chan et al., 2003, 2015; Chen et al., 2004; Chu et al., 2004; Li & De Clercq, 2020). Hence, it is a good strategy to discover anti-COVID-19 drugs from approved drug libraries for it can dramatically shorten development time.

SARS-CoV-2 belonging to beta coronavirus has an envelope and sense single-stranded RNA (Cui et al., 2019; Letko et al., 2020). It contains four non-structural proteins: 3-chymotry psin-like (3CLpro), papain-like protease (PLpro), helicase and RNA polymerase (Perlman & Netland, 2009). Both 3CLpro and PLpro are involved in transcription and replication of the virus. Inhibitors targeting viral proteases have shown anti-coronal virus activity in vitro (Pillaiyar et al., 2016; Zumla et al., 2016). Among them, the 3CLpro is the main protease that plays a key role in the replication cycle of the virus (de Wit et al., 2016). The protease cleaves pp1a and pp1ab which are encoded by the virus ORF1a/b, and they have 96% sequence similarity with the 3CLpro of the SARS-CoV that caused an outbreak in 2003 (Liu et al., 2020; Perlman & Netland, 2009).

Coronavirus protease inhibitors show antiviral activity in vitro. In this study, we used virtual screening technology to discover potential drugs targeting the 3CLpro of SARS-CoV-2 from approved drug library and the obtained candidates might be potential inhibitors for further activity detection and molecular modification.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Homologous modeling and protein structure alignment

Crystal structures of the 3CLpro of both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV were obtained from Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). The 3CLpro structure file (PDB ID: 6LU7) of SARS-CoV-2 has a resolution of 2.16 Å and the 3CLpro structure file (PDB ID:2Z9J) of SARS-CoV has a resolution of 1.95 Å (Lee et al., 2007). The protein sequences (YP_009725301.1 and NP_828863.1) were obtained from NCBI. Homologous modeling of 3CLpro of SARS-CoV-2 was performed by using 2Z9J as a template and the SWISS-MODEL online server (Bienert et al., 2017; Waterhouse et al., 2018). The VMD RMSD tool was used to calculate the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of this model from the 3CLpro crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 (Humphrey et al., 1996).

2.2. Virtual screening of 3CLpro active regions of SARS-CoV-2

Prepare the 3CLpro crystal structure file (PDB ID: 6LU7). Structural coordinates included 3CLpro, ligand N3 and water molecules. The step of protein pretreatment was performed by removing ligands and crystal water, then adding hydrogen atoms according to the amino acid protonation state at pH 7.0.

Approved drug library containing 5903 molecules was obtained from ZINC15 (http://zinc15.docking.org/) (Sterling & Irwin, 2015).

Molecular docking was performed by using LeDock software (http://www.lephar.com/). This method was based on a combination of simulated annealing and genetic algorithm to optimize the position and orientation of the ligands. And score given was based on physical and empirical methods (Zhao & Caflisch, 2014). The putative catalytic dyad (Cys-145 and His-41) and substrate-binding pocket regions were selected as docking regions in this protease (Anand et al., 2003). Binding energy was calculated by molecular docking of the receptor protein with each drug and sequencing by their scores. The molecules with binding energy less than −11 kcal/mol were selected as candidate drugs (Zhang & Zhao, 2016).

2.3. Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics simulation to verify the stability of the docking complex of 3CLpro and drug candidate in ionic solvent. All-atom molecular dynamics simulation was performed using Gromacs 2019.3, and the force field was selected as CHARMM36 (Van Der Spoel et al., 2005). The drug molecular topology files were generated by SwissParam (Zoete et al., 2011). Create a dodecahedron simulation box, and then set periodic boundary conditions for the box in three spatial dimensions. The minimum distance between the protein–ligand complex and the simulation box in the X, Y, and Z directions is 1.2 nm. First, the complex entered the box, and then the energy of the complex was minimized in a hypothetical vacuum. Next, add water (Model: TIP3P) to fill the simulation box as a solvent, and add sodium ion and chloride ion to maintain the system's electrostatic charge balance. Eventually, the ionic concentration of the solution reached 150 mM. After the solvent was added, the energy of the complex was minimized again. Subsequently, a pre-equilibrium simulation was performed through temperature coupling and pressure coupling. During the pre-equilibrium simulation, the heavy atoms of the complex were confined to a defined position, and the solvent could diffuse freely. The reference temperature of the coupling was set to 300 K, and the dispersion was corrected by EnerPres. The pressure was controlled by the Parrinello–Rahman method, and the reference pressure was set to 1.0 bar. The LINCS method was used to constrain all bonds. The frequency of output analog coordinates was set to 10 ps, and the frequency of saving speed and energy was 10 ps. The calculation method of long-range electrostatic interaction was PME ((Particle Mesh Ewald)), and the cut-off value of electrostatic action was set to 1.0 nm. The calculation method of van der Waals action was cut-off, and the step size was set to 2 fs. A 500 ns simulation was performed after the pre-balance simulation, and a total of about 90 G data was collected.

2.4. Binding free energy calculation based on MM-PBSA method

Interaction free energies were estimated by molecular mechanics Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) method. MM-PBSA method was used to calculate the binding free energy by g_mmpbsa (Baker et al., 2001; Kumari et al., 2014). The enthalpy of the system was calculated by molecular mechanics (MM) method and the contribution of the polar and non-polar parts of the solvent effect to free energy was determined by solving the Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) equation and calculating the molecular surface area (SA).

Potential energy in vacuum, polar solvation energy and non-polar solvation energy were calculated by g_mmpbsa. The python script provided in the g_mmpbsa package was used to calculate the average binding energy and standard deviation.

Balanced trajectory was intercepted from the RMSD curve of each protein–drug complex by MD simulation, and the MM-PBSA calculation was performed using the above method with the following modification. Considering that g_mmpbsa only read the files of some specific Gromacs versions, the binary run input file (.tpr) required for MM-PBSA calculation through the g_mmpbsa was regenerated by Gromacs 5.1.2. The molecular structure file (.gro), topology file (.top) and MD-parameter file (.mdp) were necessary to generate the binary run input file, and they all came from the MD process.

2.5. Visualization and figures

Alignment between crystal structure and binding mode was visualized by Pymol (https://pymol.org). Protein–ligand interaction pattern diagram was shown by Discovery Studio 2016. The trajectory of the protein–ligand complex in molecular dynamics simulation was visualized by Pymol and displayed by movie. The graphs of RMSD and hydrogen bonds were plotted using GraphPad.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. 3CLpro amino acid sequence and structure analyses

By comparing the 3CLpro structures of the two SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV viruses, the secondary structure and tertiary structure of the two 3CLpro did not change significantly near the crack between domains 1 and 2 (supplementary Figure S1(A)). By analyzing amino acid sequence, their two 3CLpros reached 96% identity, and there were no significant changes in the main polar amino acids and charged amino acids (supplementaryFigures S1(B) and S2(C)). Based on the structure of 3CLpro of SARS-CoV, homology modeling was performed. The model was compared with the crystal structure of 3CLpro of SARS-CoV-2 and the results showed that the RMSD was 0.78 (results not shown). It was shown that 3CLpro of SARS-CoV-2 and 3CLpro of SARS-CoV may have substantially the same catalytic mode. Therefore, drug candidates can be analyzed based on 3CLpro related research experience on SARS-CoV.

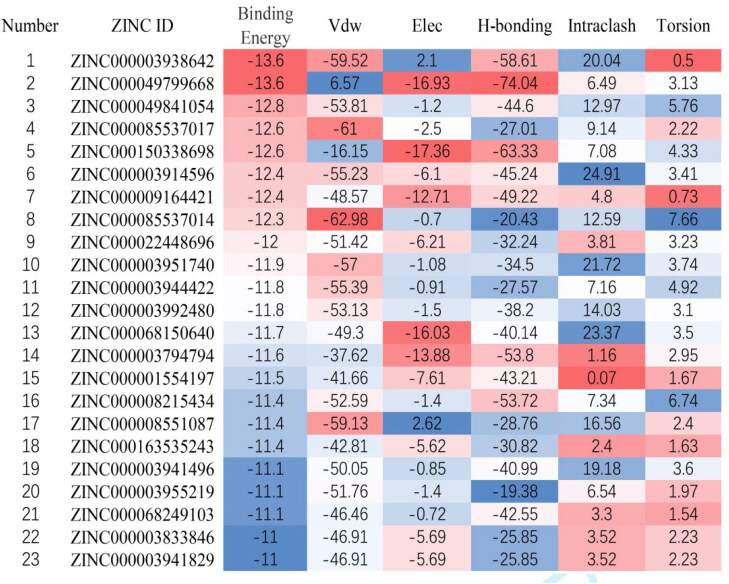

Figure 1.

Virtual screening results of drug candidates. Drugs were sorted according to the docking binding energy, corresponding to the order in Table 1. Unit: kcal/mol.

3.2. Virtual screening of molecules targeting 3CLpro from approved drug library

By using virtual screening, 23 approved drugs with binding energy below −11 kcal/mol were obtained as candidate drugs (Figure 1). The result included seven peptides or peptide analogs and 17 small molecule drugs (Table 1 and Figure 1). According to their characteristics, 10 out of 23 drugs were protease inhibitors, of which nine drugs were HIV-1 protease inhibitors. It was suggested that the drug structure of the protease inhibitor was hit with a high probability.

Table 1.

Drug candidate information.

| Number | Drug | Molecular type | Target | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Thymopentin | Peptide | T lymphocyte | Viral infection |

| 2 | Viomycin | Peptidomimetic | Bacterial ribosomes | Bacterial infections |

| 3 | Carfilzomib | Peptidomimetic | 20S Proteasome | Tumor |

| 4 | Cangrelor | Purine Nucleotides | P2Y12 | Anticoagulation |

| 5 | Capastat | Peptidomimetic | Bacterial ribosomes | Bacterial infections |

| 6 | Saquinavir | Quinolines | HIV-1 protease | HIV infection |

| 7 | Ceftolozane | Amides | PBPs | Bacterial infections |

| 8 | Cobicistat | Thiazoles | CYP3A | HIV infection |

| 9 | Indinavir | Pyridines | HIV-1 protease | HIV infection |

| 10 | Lopinavir | Pyrimidinones | HIV-1 protease | HIV infection |

| 11 | Ritonavir | Thiazoles | HIV-1 protease | HIV infection |

| 12 | Telaprevir | Peptidomimetic | HIV-1 protease | HIV infection |

| 13 | Plazomicin | Glycosides | Bacterial ribosomes | Bacterial infections |

| 14 | Mitoxantrone | Anthracyclines | DNA and topoisomerase II | Tumor |

| 15 | Macimorelin | Peptidomimetic | GHS-R1a | Growth hormone deficiency |

| 16 | FAD | Purine nucleotides | Prosthetic | Adjuvant therapy |

| 17 | CoA | Purine nucleotides | Coenzymes | Adjuvant therapy |

| 18 | Valrubicin | Anthracyclines | DNA and topoisomerase II | Tumor |

| 19 | Atazanavir | Peptidomimetic | HIV-1 protease | HIV infection |

| 20 | Darunavir | Amides | HIV-1 protease | HIV infection |

| 21 | Encorafenib | Amides | BRAF kinase | Tumor |

| 22 | Nelfinavir | Isoquinolines | HIV-1 protease | HIV infection |

| 23 | Fosamprenavir | Amides | HIV-1 protease | HIV infection |

Currently, both Ritonavir and Lopinavir are used as a frontline treatment of COVID-19 and were found in the result of virtual screening (Figure 2). They also had relatively consistent predicted binding energy (−11.8 kcal/mol and −11.9 kcal/mol, respectively).

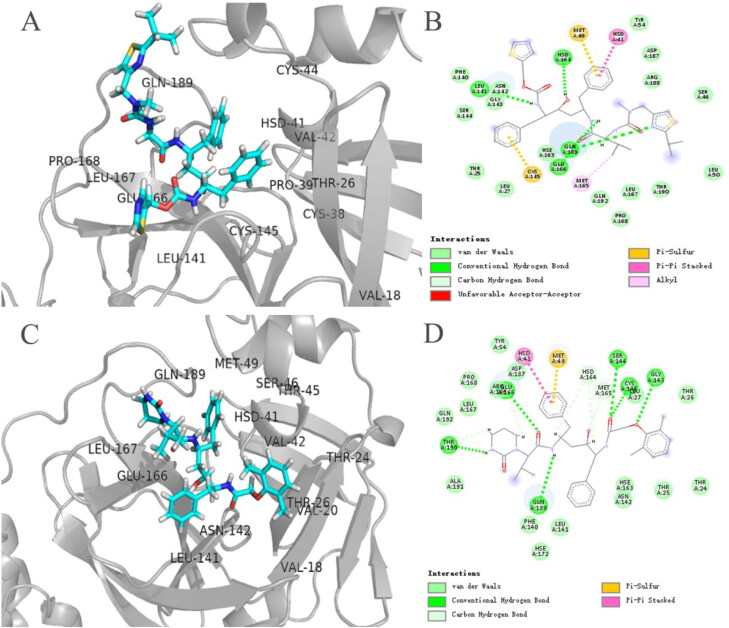

Figure 2.

Binding patterns of Ritonavir and Lopinavir to 3CLpro. (A and C) The three-dimensional binding modes of Ritonavir and Lopinavir with 3CLpro, respectively. Protein shown as a cartoon model and ligands shown as stick model. (B and D) The interaction modes of both Ritonavir and Lopinavir with 3CLpro, respectively.

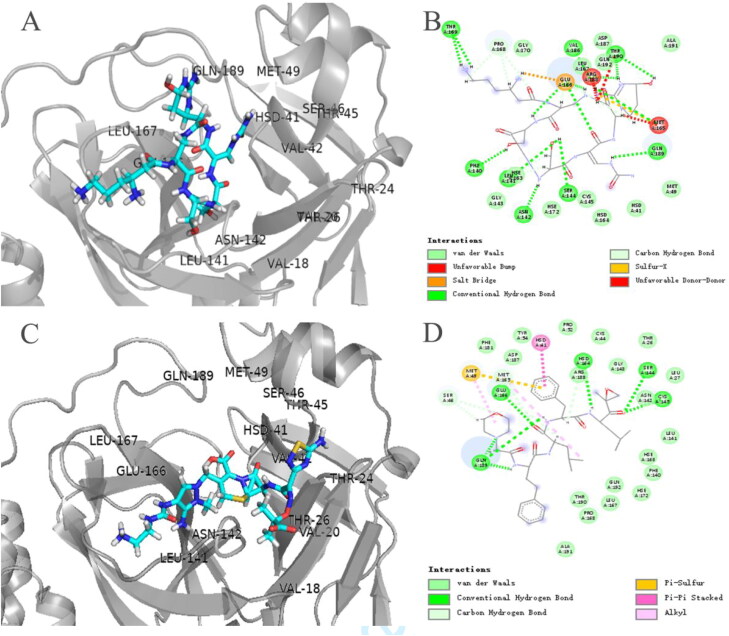

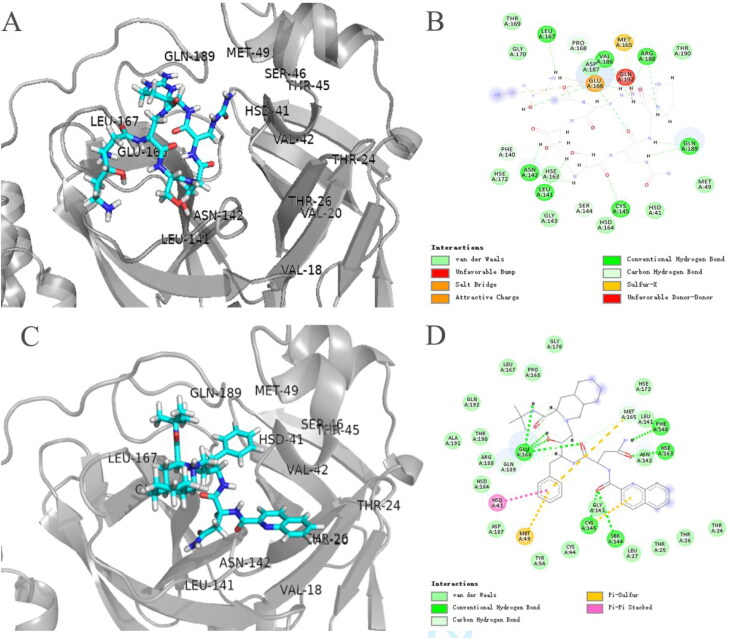

Among protease inhibitors, Carfilzomib (ZINC000049841054), Saquinavir (ZINC000003914596) and Indinavir (ZINC000022448696) have better docking scores (Figure 1). As antitumor drug, Carfilzomib exerted its effect by binding to the active site of the 20S proteasome, which contained chymotrypsin whose spatial structure is like the 3CLpro. The docking results showed that the Carfilzomib was in 3CLpro's pocket consisting of S1 and S2 subsites (Figure 3(C)) and formed π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding with HIS-41 and CYS-145, respectively, in which were catalytic duplexes. The Carfilzomib also had multiple non-covalent interactions with MET-165 at the S1 subsite and MET-49 at the S2 subsite (Figure 3(D)). Besides, both Saquinavir and Lopinavir had similar binding patterns (Figures 4(C) and 2(C)), and both stabilized HIS-41 and MET-49 in the same way. The non-covalent binding pattern of the Saquinavir and HIS-41 was similar to that of Carfilzomib, in which formed π–π stacks. The benzene ring interacted with MET-165 at the S3 subsite and MET-49 at the S2 subsite, and HIS-163 at the S2 subsite also formed a hydrogen bond interaction with Saquinavir. All three drugs formed hydrogen bonds with CYS-145. The results showed that Saquinavir and Lopinavir may have similar mechanism. And docking scores of Indinavir and Lopinavir were almost the same, but the combination mode was less than Saquinavir (supplementary Figure S3(C) and Figure 2(C)).

Figure 3.

The three-dimensional binding modes of Viomycin and Carfilzomib with 3CLpro. (A and C) The three-dimensional binding modes of Viomycin and Carfilzomib with 3CLpro, respectively. Protein shown as a cartoon model and ligands shown as stick model. (B and D) The interaction modes of both Viomycin and Carfilzomib with 3CLpro, respectively.

Figure 4.

The three-dimensional binding modes of Capastat and Saquinavir with 3CLpro. (A and C) The three-dimensional binding modes of Capastat and Saquinavir with 3CLpro, respectively. Protein shown as a cartoon model and ligands shown as stick model. (B and D) The interaction modes of both Capastat and Saquinavir with 3CLpro, respectively.

The top three drugs with docking scores were peptides or peptide analogs (Table 1). Among them, Thymopentin got the highest score. It was able to bind 3CLpro's substrate-binding pocket. Not only it can bind 3CLpro's catalytic dyad Cys-145 and His-41, but also HIS-163, Glu166 at the S1 subsite and ASP-187 at the S2 subsite (supplementary Figure S4(A) and (B)). It is well known that Thymopentin targets the lymphocytes as regulator in immune system, so it can be used for adjuvant treatment of viral infections. No inhibitory effect on proteases has been reported until we got the results of virtual screening.

Among non-protease inhibitor drugs, Viomycin, Cangrelor, Capastat and Cobicistat also have higher predicted scores than Lopinavir. Two of them, Viomycin and Capastat, are aminoglycoside antibiotics. Viomycin completely occupies the S1 subsite and binds to HIS-163, PHE-140, MET-165 and GLU-166. But it did not bind to His-41 and CYS-145 at the catalytic dyad (Figure 3(A) and (B)). Cangrelor can form hydrogen bonds with CYS-145 in the catalytic dyad, and effectively occupied the S1 and S3 subsites of 3CLpro (supplementary Figure S2(A) and (B)). Capastat also binds well to the S1 and S3 subsites but no significant interaction was with amino acids at the S2 subsite, and hydrogen bonds with CYS-145 in the catalytic dyad (Figure 4(A)). Ceftolozane interacts with the S1 subsite of 3CLpro and HIS-41 in the catalytic dyad (supplementary Figure S2(C)). Cobicistat was able to combine with the catalytic dyad of 3CLpro, and its combined poste was better than Indinavir (supplementary Figure S3(A)).

Among protease inhibitors, Telaprevir, Atazanavir, Darunavir, Nelfinavir and Fosamprenavir were also selected to be candidates. However, their predicted binding power was weaker than that of the Lopinavir. Telaprevir mainly interacts with the catalytic dyad and has less interaction with the peptide binding site (supplementary Figure S4).

In brief, the 23 approved drugs were identified to have the effect on inhibiting 3CLpro by virtual screening. Among them, Ritonavir and Lopinavir have been currently used to treat COVID-19. And among the rest of 21 candidates, Carfilzomib, Saquinavir and Thymopentin showed more promising against SARS-CoV-2.

3.3. Molecular dynamic analysis of the combined posture of the 3CLpro and drug candidates

In order to further characterize the interaction between the candidate drug and 3CLpro, molecular dynamics simulation and binding free energy calculation based on the MM-PBSA method were performed. Because Ritonavir and Lopinavir are currently used in clinical trials for the treatment of COVID-19, the drugs that were superior to Ritonavir and Lopinavir in the virtual screening results were selected for further analysis.

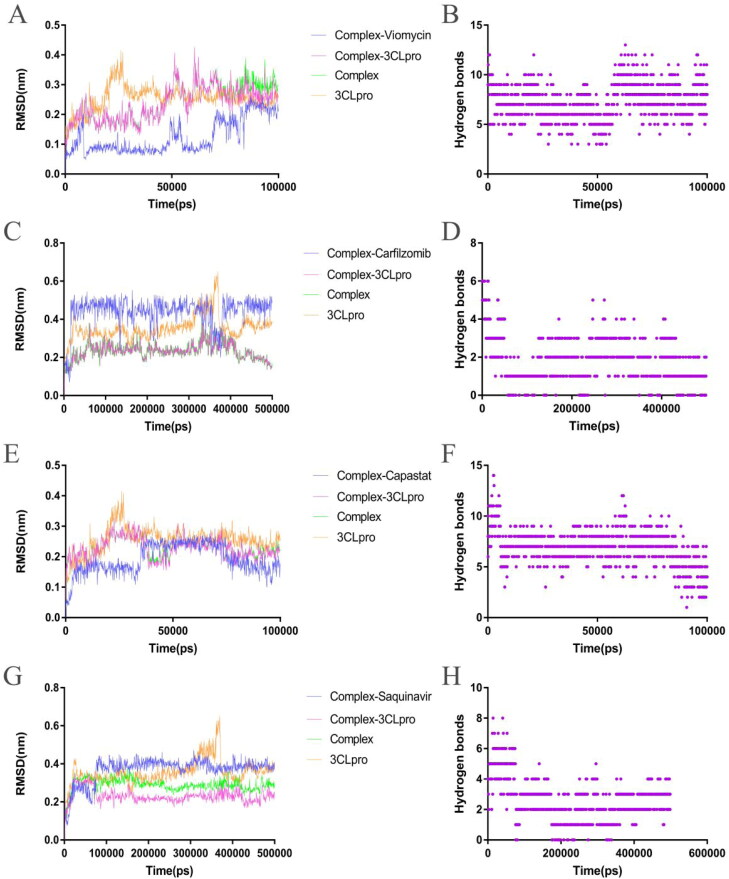

3.3.1. RMSD

RMSD is an important index for quantifying the structural stability of protein–drug complexes. By comparing the RMSD between the 3CLpro in the complex and the 3CLpro in the free state, it can be understood whether the stability of the 3CLpro protein has changed under the action of the drug. The RMSD of the drug–protein complex can reflect whether the drug can form a stable complex with the protein, and the RMSD of the drug molecule in the complex can reflect whether the binding posture of between the drug and the protein was stable.

The RMSD of the Viomycin–3CLpro complex maintained a temporary balance after 10 ns. The RMSD of Viomycin and protein in the complex fluctuated simultaneously at 45 ns, and gradually returned to equilibrium after 60 ns (Figure 5(A)). The RMSD of the free 3CLpro remained balanced from 30 to 100 ns. In this process, Viomycin always maintains the interaction with 3CLpro, indicating that the Viomycin had disturbed the structure of the 3CLpro (Supplementary Movie 1). The RMSD of the Carfizomib–3CLpro complex remained balanced after 5 ns, and then a slight fluctuation occurred from 35 to 45 ns. The RMSD of the free 3CLpro fluctuated violently from 35 to 45 ns. The result suggested that the structural fluctuation of the complex may be caused by the 3CLpro protein itself (Figure 5(C).

Figure 5.

Analysis of molecular dynamics simulation results of the free 3CLpro and the 3CLpro–drug complex. (A) Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the 3CLpro–Viomycin complex and the free 3CLpro. (B) Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the Viomycin and the 3CLpro. (C) RMSD of the 3CLpro–Carfilzomib complex and the free 3CLpro. (D) Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the Carfilzomib and 3CLpro. (E) RMSD of the 3CLpro–Capastat complex and the free 3CLpro. (F) Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the Capastat and 3CLpro. (G) RMSD of the 3CLpro–Saquinavir complex and the free 3CLpro. (H) Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the Saquinavir and 3CLpro.

The RMSD of the Carfizomib in the complex quickly remained stable after 2 ns, and then a fluctuation occurred from 35 to 40 ns, which is consistent with the fluctuation time of 3CLpro. At other times, the RMSD of the Carfizomib remained stable, indicating that the combined posture of Carfizomib and 3CLpro was consistent (Figure 5(C) and Supplementary Movie 5). The RMSD curves of the Capastat–3CLpro complex and the 3CLpro in the complex basically overlap, indicating that the main fluctuation was caused by the 3CLpro. The RMSD of the Capastat in the complex occurred a short-term fluctuation at 35 ns, and then remained balanced to 70 ns. After 70 ns, the RMSD curve decreased until the end of the simulation. In the simulation process, the Capastat always maintained the combination with 3CLpro (Figure 5(E) and Supplementary Movie 2).

The Saquinavir–3CLpro complex quickly remained balanced after 5 ns until the simulation ended. The RMSD of the Saquinavir in the complex showed no significant fluctuations after 6 ns, indicating that the combined posture of the drug and the 3CLpro was stable (Figure 5(G) and Supplementary Movie 6).

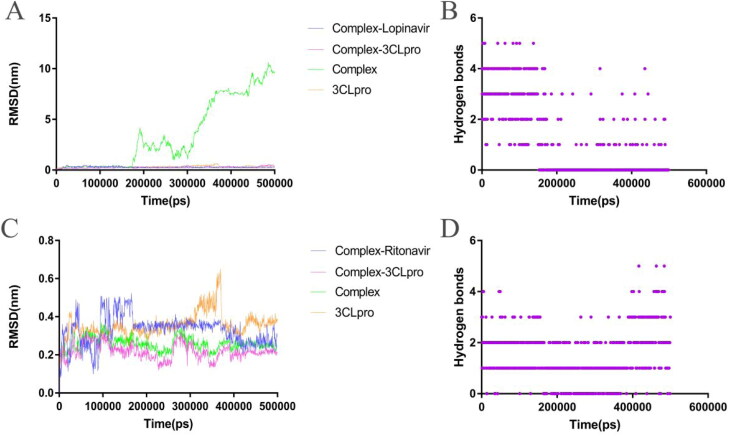

The RMSD value of the Lopinavir–3CLpro complex increased rapidly after 160 ns, indicating that the Lopinavir completely detached from the 3CLpro and did not bind again until the end of the simulation (Figure 6(A) and Supplementary Movie 4). The RMSD of the Ritonavir–3CLpro complex did not completely enter the equilibrium state in the first 400 ns of the simulation, while the RMSD of the Ritonavir in the complex ended a violent fluctuation around 150 ns and entered a relatively equilibrium state (Figure 6(C) and Supplementary Movie 3).

Figure 6.

Analysis of molecular dynamics simulation results of the free 3CLpro and the 3CLpro–drug complex. (A) RMSD of the 3CLpro–Lopinavir complex and the free 3CLpro. (B) Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the Lopinavir and 3CLpro.

Although the RMSD of the Thymopentin–3CLpro complex did not fluctuate violently during the simulation, the curve was always rising and did not enter a complete equilibrium state. The RMSD curve of the Thymopentin in the complex entered equilibrium after 75 ns, while the RMSD curve of the 3CLpro in the complex occurred as a small fluctuation at 75 ns (supplementary Figure S5(A)). Molecular simulation results showed that the binding posture of the Cangrelor and the 3CLpro remained stable at the beginning. Although most of the groups failed to interact with the 3CLpro, they never disengaged from the 3CLpro's active pocket (supplementary Figure S5(C)). During the simulation, Ceftolozane adjusted the binding posture with 3CLpro and lost the binding with the amino acid of 3CLpro's active pocket. The RMSD of the complex also showed large fluctuations and the ligand failed to form a stable binding mode with the active pocket of the 3CLpro (supplementary Figure S5(E)). The Cobicistat–3CLpro complex quickly remained stable after the simulation was started, but the RMSD of the Cobicistat in the complex showed large fluctuations, indicating that most functional groups did not form a good bond with the 3CLpro (supplementary Figure S5(G)). In about 50 ns of the simulation, the RMSD of the 3CLpro–Indinavir complex fluctuated greatly (supplementary Figure S5(I)), and the Indinavir broke away from the active pocket of 3CLpro (results not shown), but the ligand was not completely separated from the 3CLpro and still maintained hydrogen bond interactions with the 3CLpro (Figure 5(J)).

3.3.2. Intermolecular H-bonding

The hydrogen bond between protein and drug is a key parameter for evaluating the binding affinity between drug and receptor. The number and degree of change of the hydrogen bond can reflect the strength and stability of the binding affinity between drug and protein receptor.

During the simulation, the Viomycin and the Capastat always maintained hydrogen bonding interactions with 3CLpro (Figure 5(B) and (F)). However, the hydrogen bonding interaction of other drug candidates with the 3CLpro occasionally disappeared temporarily. The results showed that the Viomycin and the Capastat had higher stability on the interaction of 3CLpro compared with other drug candidates. The number of hydrogen bonds is an important index to reflect the binding affinity of the ligand to the receptor. The average hydrogen bond formed by between the Viomycin and the 3CLpro was 7, which was the same as the Capastat. The Viomycin and the Capastat had a higher number of hydrogen bonds with 3CLpro than other drugs. The average number of hydrogen bonds formed by the Ritonavir with 3CLpro was 1, while the average number of hydrogen bonds formed by the Cangrelor and the Cobicistat with the 3CLpro was 0.7 and 0.4, respectively (supplementary Figure S5(D) and (H)). The average number of hydrogen bonds formed by the Thymopentin with the 3CLpro was 6, but the number of hydrogen bonds changed drastically (supplementary Figure S5(B)). The average number of hydrogen bonds formed by the Ceflolozane with the 3CLpro was 4 (supplementary Figure S5(F)), and there was basically no significant fluctuation in the number of hydrogen bonds. The average number of hydrogen bonds formed by Carfilzomib, Saquinavir and Indinavir with 3CLpro was higher than that of Ritonavir, which is 2, 3 and 2, respectively (Figure 5(D), (H) and supplementary Figure S5(J)).

3.3.3. Binding free energy calculation based on MM-GBSA method

MM-PBSA method was used to calculate the binding free energy of the protein–ligand complex. In this study, some drugs which had stable binding to 3CLpro in MD simulations were selected for further analysis. A total of 250 frames representing the protein–ligand conformations at the last 20 ns of simulation run were extracted to calculate the MM/GBSA free binding energy. The results showed that the Viomycin and the Capastat had strong binding affinity with the 3CLpro, and their binding energies were −434.558 and 417.508 kJ/mol, respectively. The energy types are divided into van der Waals energy, Electrostattic energy, Polar Solvation energy and SASA energy. The results showed that Electrostatic energy and van der Waals energy were the main contributors to the binding energy of these two drugs with the 3CLpro (Table 2).

Table 2.

Binding energy between 3CLpro and drug through MM/PBSA estimation.

| Drug | van der Waals energy (kJ/mol) | Electrostatic energy (kJ/mol) | Polar solvation energy (kJ/mol) | SASA energy (kJ/mol) | Binding energy (kJ/mol) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymopentin | −125.466 ± 18.959 | −537.179 ± 55.689 | 749.810 ± 57.503 | −23.294 ± 1.362 | 63.871 ± 29.978 | ||

| Viomycin | −179.319 ± 20.784 | −957.938 ± 82.794 | 726.672 ± 101.092 | −23.972 ± 1.796 | −434.558 ± 41.901 | ||

| Carfilzomib | −206.769 ± 13.264 | −29.350 ± 8.014 | 156.571 ± 30.216 | −23.624 ± 1.741 | −103.171 ± 30.589 | ||

| Cangrelor | −181.441 ± 15.817 | 423.415 ± 63.622 | 161.110 ± 46.512 | −17.997 ± 1.696 | 385.087 ± 57.161 | ||

| Capastat | −158.384 ± 21.901 | −757.295 ± 48.755 | 517.467 ± 53.150 | −19.297 ± 1.987 | −417.508 ± 32.084 | ||

| Saquinavir | −165.223 ± 13.454 | −263.284 ± 20.006 | 227.142 ± 26.126 | −20.837 ± 1.405 | −222.202 ± 19.214 | ||

| Cobicistat | −135.180 ± 14.865 | −17.251 ± 8.814 | 88.703 ± 22.972 | −15.930 ± 1.898 | −79.658 ± 25.762 | ||

| Indinavir | −27.339 ± 18.064 | −367.190 ± 31.740 | 283.644 ± 54.304 | −7.292 ± 1.958 | −118.178 ± 48.942 | ||

| Ritonavir | −243.618 ± 21.755 | −36.181 ± 15.885 | 168.434 ± 24.803 | −27.149 ± 2.108 | −138.515 ± 24.306 | ||

Among them, the electrostatic energy between the Viomycin and the 3CLpro was −957.938 kJ/mol, which was the main contributing factor of binding energy. However, the Polar solvation energy between the Viomycin and the 3CLpro was positive, which was not conducive to the stability of the complex. As a reference drug, the binding energy of the Ritonavir was −138.515 kJ/mol, of which van der Waals energy contributed the most to the binding energy, but Polar solvation energy was the main limiting factor. Among them, the binding energies of Carfilzomib, Saquinavir and Indinavir were close to that of Ritonavir, and their binding energy was −103.171, −222.202 and −118.178 kJ/mol, respectively, indicating that these three drugs may have similar binding affinity with the Ritonavir. The binding energy between the Cobicistat and the 3CLpro was −79.658 kJ/mol, while both Thymopentin and Cangrelor were difficult to form a stable complex with the 3CLpro, respectively.

4. Conclusion

Due to the rapid outbreak of COVID-19 worldwide, finding anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs is an urgent task. However, the development of new antiviral drugs by traditional methods needs take a long time. Thus, considering the urgency of finding anti-COVID-19 drugs, it is a good strategy to discover inhibitors from approved drug libraries for it can dramatically shorten development time. In addition, the indications and toxic side effects of these drugs are known, they can be used immediately to treat COVID-19 once they have anti-SARS-CoV-2 effect. 3CLpro is conserved in sequence and has known structural biological characteristics. Evaluating potential 3CLpro inhibitors from approved drug library by virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulation is a feasible strategy.

As an aminoglycoside antibiotic, Viomycin’s anti-tuberculosis mechanism was similar to the Capastat. Molecular docking and dynamics simulation results showed that these two drugs had high affinity with the active pocket of the 3CLpro, respectively. Based on the MM-PBSA method, the binding free energy calculation results suggested that both were also superior to currently all other approved drugs, indicating that they may be potential candidates for the treatment of COVID-19.

The calculation results suggested that the binding free energy of both Carfilzomib and Saquinavir with 3CLpro was close to Ritonavir. Since Carfilzomib's mechanism includes inhibition of chymotrypsin activity, it may better target 3CLpro prospectively.

Although the docking results of Saquinavir and Lopinavir were similar, in dynamics simulations, the Saquinavir was able to stably bind to the 3CLpro, while the Lopinavir was separated from the 3CLpro. And the binding free energy between the Saquinavir and the 3CLpro was superior to the Ritonavir. Although all three drugs are HIV protease inhibitors, in this study, Saquinavir had better prediction results.

We noticed Ritonavir/Lopinavir being clinically tested for the treatment of COVID-19 is an aspartate protease inhibitor. Their molecular structure is optimized for the aspartic protease spatial structure of HIV. But 3CLpro is a cysteine protease. The difference in the spatial structure of 3CLpro and HIV protease may lead to the actual inhibition efficiency. Hence, Ritonavir and Lopinavir are needed to further evaluate their effects when they resist SARS-CoV-2.

By molecular docking, dynamics simulation and binding free energy calculation based on the MM-PBSA method, we found that Viomycin, Capastat, Carfilzomib and Saquinavir had potential 3CLpro inhibitory activity. Simultaneously, all predicted results showed that the Viomycin and the Capastat outperformed the Ritonavir and the Lopinavir. Although this result is exciting enough, current computational biology methods cannot fully simulate physiological conditions, so further verification in vitro is needed to confirm the above results. The results of this research may help accelerate the development of antiviral drugs based on approved drug libraries and help people cope with this new disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We really appreciate that the Zihe Rao team of Shanghai Tech University shared the coordinate files of the 3CLpro crystal structure for us to conduct the study. We also thank that Miss. Marilou Ochivillo kindly gave language editing of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Operating Fund of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Bioengineering Medicine [No. 2014B030301050].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Anand, K., Ziebuhr, J., Wadhwani, P., Mesters, J. R., & Hilgenfeld, R. (2003). Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: Basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science (New York, N.Y.), 300(5626), 1763–1767. 10.1126/science.1085658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, N. A., Sept, D., Joseph, S., Holst, M. J., & McCammon, J. A. (2001). Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98(18), 10037–10041. 10.1073/pnas.181342398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert, S., Waterhouse, A., de Beer, T. A., Tauriello, G., Studer, G., Bordoli, L., & Schwede, T. (2017). The SWISS-MODEL Repository-new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(D1), D313–D319. 10.1093/nar/gkw1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J. F., Yao, Y., Yeung, M. L., Deng, W., Bao, L., Jia, L., Li, F., Xiao, C., Gao, H., Yu, P., Cai, J. P., Chu, H., Zhou, J., Chen, H., Qin, C., & Yuen, K. Y. (2015). Treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir or interferon-beta1b improves outcome of MERS-CoV infection in a nonhuman primate model of common marmoset. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 212(12), 1904–1913. 10.1093/infdis/jiv392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. S., Lai, S. T., Chu, C. M., Tsui, E., Tam, C. Y., Wong, M. M., Tse, M. W., Que, T. L., Peiris, J. S., Sung, J., Wong, V. C., & Yuen, K. Y. (2003). Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome with lopinavir/ritonavir: A multicentre retrospective matched cohort study. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 9, 399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Chan, K. H., Jiang, Y., Kao, R. Y., Lu, H. T., Fan, K. W., Cheng, V. C., Tsui, W. H., Hung, I. F., Lee, T. S., Guan, Y., Peiris, J. S., & Yuen, K. Y. (2004). In vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. Journal of Clinical Virology: The Official Publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology, 31(1), 69–75. 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C. M., Cheng, V. C., Hung, I. F., Wong, M. M., Chan, K. H., Chan, K. S., Kao, R. Y., Poon, L. L., Wong, C. L., Guan, Y., Peiris, J. S., Yuen, K. Y., & Group, H. U. S. S. (2004). Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: Initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax, 59(3), 252–256. 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson, P., Rolain, J. M., Lagier, J. C., Brouqui, P., & Raoult, D. (2020). Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 55(4), 105932. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J., Li, F., & Shi, Z. L. (2019). Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses . Nature Reviews. Microbiology, 17(3), 181–192. 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit, E., van Doremalen, N., Falzarano, D., & Munster, V. J. (2016). SARS and MERS: Recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nature Reviews. Microbiology, 14(8), 523–534. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, W., Dalke, A., & Schulten, K. (1996). VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics, 14(1), 33–38, 27-38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, R., Kumar, R., Open Source Drug Discovery, C., & Lynn, A. (2014). g_mmpbsa – A GROMACS tool for high-throughput MM-PBSA calculations. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 54(7), 1951–1962. 10.1021/ci500020m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. C., Kuo, C. J., Hsu, M. F., Liang, P. H., Fang, J. M., Shie, J. J., & Wang, A. H. (2007). Structural basis of mercury- and zinc-conjugated complexes as SARS-CoV 3C-like protease inhibitors. FEBS Letters, 581(28), 5454–5458. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letko, M., Marzi, A., & Munster, V. (2020). Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nature Microbiology, 5(4), 562–569. 10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G., & De Clercq, E. (2020). Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 19(3), 149–150. 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W., Morse, J. S., Lalonde, T., & Xu, S. (2020). Learning from the past: Possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019-nCoV. Chembiochem: A European Journal of Chemical Biology, 21(5), 730–738. 10.1002/cbic.202000047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, S., & Netland, J. (2009). Coronaviruses post-SARS: Update on replication and pathogenesis. Nature Reviews. Microbiology, 7(6), 439–450. 10.1038/nrmicro2147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillaiyar, T., Manickam, M., Namasivayam, V., Hayashi, Y., & Jung, S. H. (2016). An overview of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 3CL protease inhibitors: Peptidomimetics and small molecule chemotherapy. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 59(14), 6595–6628. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, T., & Irwin, J. J. (2015). ZINC 15 – ligand discovery for everyone. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 55(11), 2324–2337. 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touret, F., & de Lamballerie, X. (2020). Of chloroquine and COVID-19. Antiviral Research, 177, 104762. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Spoel, D., Lindahl, E., Hess, B., Groenhof, G., Mark, A. E., & Berendsen, H. J. (2005). GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 26(16), 1701–1718. 10.1002/jcc.20291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M., Cao, R., Zhang, L., Yang, X., Liu, J., Xu, M., Shi, Z., Hu, Z., Zhong, W., & Xiao, G. (2020). Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Research, 30(3), 269–271. 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, A., Bertoni, M., Bienert, S., Studer, G., Tauriello, G., Gumienny, R., Heer, F. T., de Beer, T. A. P., Rempfer, C., Bordoli, L., Lepore, R., & Schwede, T. (2018). SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic acids Research, 46(W1), W296–W303. 10.1093/nar/gky427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N., & Zhao, H. (2016). Enriching screening libraries with bioactive fragment space. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 26(15), 3594–3597. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H., & Caflisch, A. (2014). Discovery of dual ZAP70 and Syk kinases inhibitors by docking into a rare C-helix-out conformation of Syk. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 24(6), 1523–1527. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.01.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoete, V., Cuendet, M. A., Grosdidier, A., & Michielin, O. (2011). SwissParam: A fast force field generation tool for small organic molecules. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 32(11), 2359–2368. 10.1002/jcc.21816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumla, A., Chan, J. F., Azhar, E. I., Hui, D. S., & Yuen, K. Y. (2016). Coronaviruses – drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery, 15(5), 327–347. 10.1038/nrd.2015.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.