Abstract

Cronobacter species are opportunistic pathogens capable of causing life-threatening infections in humans, with serious complications arising in neonates, infants, immuno-compromised individuals, and elderly adults. The genus is comprised of seven species: Cronobacter sakazakii, Cronobacter malonaticus, Cronobacter turicensis, Cronobacter muytjensii, Cronobacter dublinensis, Cronobacter universalis, and Cronobacter condimenti. Despite a multiplicity of genomic data for the genus, little is known about likely transmission vectors. Using DNA microarray analysis, in parallel with whole genome sequencing, and targeted PCR analyses, the total gene content of two C. malonaticus, three C. turicensis, and 14 C. sakazaki isolated from various filth flies was assessed. Phylogenetic relatedness among these and other strains obtained during surveillance and outbreak investigations were comparatively assessed. Specifically, microarray analysis (MA) demonstrated its utility to cluster strains according to species-specific and sequence type (ST) phylogenetic relatedness, and that the fly strains clustered among strains obtained from clinical, food and environmental sources from United States, Europe, and Southeast Asia. This combinatorial approach was useful in data mining for virulence factor genes, and phage genes and gene clusters. In addition, results of plasmidotyping were in agreement with the species identity for each strain as determined by species-specific PCR assays, MA, and whole genome sequencing. Microarray and BLAST analyses of Cronobacter fly sequence datasets were corroborative and showed that the presence and absence of virulence factors followed species and ST evolutionary lines even though such genes were orthologous. Additionally, zebrafish infectivity studies showed that these pathotypes were as virulent to zebrafish embryos as other clinical strains. In summary, these findings support a striking phylogeny amongst fly, clinical, and surveillance strains isolated during 2010–2015, suggesting that flies are capable vectors for transmission of virulent Cronobacter spp.; they continue to circulate among United States and European populations, environments, and that this “pattern of circulation” has continued over decades.

Keywords: Cronobacter, microarray, phylogenetic analysis, whole-genome sequencing, flies as insects pests

Introduction

Cronobacter species are opportunistic foodborne pathogens that have gained attention in both research and clinical areas for their ability to cause fatal infections including meningitis, septicemia, necrotizing enterocolitis, and pneumonia in neonates (infants of 28 days or younger) and infants (Iversen and Forsythe, 2003; Yan et al., 2012; Jaradat et al., 2014; Patrick et al., 2014; Tall et al., 2014). Cronobacter species also cause septicemia, pneumonia, wound, and urinary tract infections in vulnerable adults (Iversen and Forsythe, 2003; Gosney et al., 2006; Holý et al., 2014; Patrick et al., 2014; Alsonosi et al., 2015). Infantile infections have been epidemiologically linked to consumption of intrinsically- and extrinsically contaminated lots of reconstituted powdered infant formula (PIF) (Noriega et al., 1990; Himelright et al., 2002; Henry and Fouladkhah, 2019). Furthermore, Cronobacter species have been found associated with a variety of other foods such as dried spices, nuts, ready to eat and frozen vegetables, retail foods, and relevant ecological niches such as food production environments and farms, from where they can re-distribute and contaminate finished foods posing a risk to susceptible consumers and widening the scope of public health concerns (Iversen and Forsythe, 2003; El-Sharoud et al., 2008; Osaili et al., 2009; Brandão et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2018a,b; Vasconcellos et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2019; Jang et al., 2020).

Neonates are susceptible to invasive infection with Cronobacter, defined here as a culture-positive infection emerging from a case(s) of septicemia or meningitis infections. These cases often lead to poor patient outcomes with subsequent development of chronic neurological sequelae such as hydrocephalus, permanent neurological damage and disabilities resulting in life-long health challenges or death. The reported estimated mortality rate for this age group is ∼27% (Bowen and Braden, 2006; Friedemann, 2009; Jason, 2012).

Cronobacter sakazakii, Cronobacter malonaticus, and Cronobacter turicensis are considered to be the primary pathogenic species which cause the majority of severe illnesses (Yan et al., 2012; Jaradat et al., 2014; Tall et al., 2019). Other species of Cronobacter include Cronobacter universalis, Cronobacter condimenti, Cronobacter muytjensii, and Cronobacter dublinensis, which, except for C. condimenti, have been known to cause a variety of infections in humans (Iversen et al., 2008; Joseph et al., 2012a). Surveillance data obtained by analyzing hospital records through U.S. FoodNet suggest that there is a higher percentage of Cronobacter infections observed in adults than in infants (Patrick et al., 2014). Similar findings reported by Holý et al. (2014) and Alsonosi et al. (2015) from hospitalized Czech Republic patients showed that Cronobacter infections in adults were more common than that found in infants and that C. sakazakii sequence type (ST)4 and C. malonaticus ST7 were the primary pathogens causing adult infections. Moreover, Jason (2012) showed that ∼8% (7/82) of infected infants with invasive disease consumed breast milk without supplementation with PIF or human milk fortifiers prior to onset of illness. Furthermore, reports by Bowen et al. (2017), Sundararajan et al. (2018), and McMullan et al. (2018) support these findings suggesting that infants are now being infected through contaminated expressed breast milk and nursing. Taken together, these results suggest that other unidentified sources or vectors may be involved in the transmission of Cronobacter, specifically those infections associated with adults. Thus far, these sources and vectors have been difficult to identify.

Insects, such as filth flies, have been recognized as a potential and common vector for Cronobacter and two other foodborne pathogens, Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes (Hamilton et al., 2003; Mramba et al., 2006, 2007; Pava-Ripoll et al., 2012, 2015b). Pava-Ripoll et al. (2012) showed that filth flies can harbor these foodborne pathogens on both their external body surfaces and within their alimentary canals. These authors also determined that 14% of filth flies randomly collected from dumpsters outside of urban restaurants were positive for Cronobacter both internally and/or externally, demonstrating that these flies can serve as reservoir and vector for these pathogens (Pava-Ripoll et al., 2012).

Several studies have applied sequenced-based methods such as a pan-genomic DNA microarray to identify and characterize strains obtained through surveillance activities (Tall et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2015b; Chase et al., 2017; Kothary et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2018a,b). These studies showed that microarray analysis could correctly assess the phylogenetic relatedness among persistant Cronobacter strains obtained from PIF manufacturing facilities, among strains isolated from plant-origin foods and showed that clinically relevant strains were phylogenetically related to these plant-associated strains, and helped to understand the nucleotide divergence of outer membrane proteins captured within outer membrane vessicles. The microarray was also able to accurately assess each strain’s identity, could differentiate Cronobacter species from phylogenetically related species, and was a useful tool to assess phylogenetic relatedness and gene content among strains.

In this paper, we explore the likely possibility that strains associated with filth flies are related to strains obtained from other sources and this information supports the hypothesis that flies may serve as vectors for clinically relevant Cronobacter. The results presented in this study suggests that filth fly isolates are phylogenetically related to Cronobacter strains recovered from clinical, food, and environmental sources using the above described pan genomic microarray in parallel with whole genome sequencing and targeted PCR analyses. Virulence of a subset of strains was assessed using a recently described zebrafish embryo model of infection (Fehr et al., 2015; Eshwar et al., 2016). Lastly, the results from this study demonstrate the usefulness of this parallel next generation sequencing approach coupled with virulence assessment of strains as discriminatory characterization and identification tools for public health and source attribution. These pathotypes were as virulent to zebrafish embryos as other clinical strains; and that they continue to circulate among the United States and European populations, environments, and filth flies.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of Cronobacter From Filth Flies

Cronobacter strains shown in Table 1 were obtained from the external surfaces and alimentary canals of wild caught adult filth flies as follows: thirteen strains were isolated from ten Musca domestica (housefly), two strains from one Sarcophaga haemorrhoidalis (red-tailed flesh fly), two strains from one Lucilia cuprina (blowfly), one strain from a Lucilia sericata (common green bottle fly), and another strain from an adult muscoide fly belonging to the family Anthomyiidae (Anthomyiidae are a large and diverse family of Muscoidea flies). Strains were isolated using the method described by Pava-Ripoll et al. (2012, 2015b). All strains are available upon request to Dr. Ben Tall at CFSAN, U.S. FDA.

TABLE 1.

Cronobacter strain and species IDs*, filth fly host species and site, Cronobacter serotype, and MLST sequence types of strains isolated during 2012 from various species of filth flies which were investigated in this study.

| Strain ID | Cronobacter species | Filth fly species, sample type | Serotype | Sequence type | Accession number |

| Md25g# | C. malonaticus | Musca domestica, house fly, alimentary canal | Cmal O:2 | 7 | MSAC00000000 |

| Md99g | C. malonaticus | M. domestica, alimentary canal | Cmal O:1 | 60 | MSAF00000000 |

| Sh41g | C. turicensis | Sarcophaga haemorrhoidalis, red-tailed flesh fly, alimentary canal | Ctur UKN | 569 | MRZS00000000 |

| Sh41s | C. turicensis | S. haemorrhoidalis, surface | Ctur UKN | 569 | MSAG00000000 |

| Md1sN | C. turicensis | M. domestica, surface | UKN | 519 | VOEL00000000 |

| Md1g | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, alimentary canal | Csak O:2 | 4 | MSAH00000000 |

| Md27gN | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, alimentary canal | Csak UKN | 93 | VOEK00000000 |

| Md33g | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, alimentary canal | Csak O:1 | 8 | MSAI00000000 |

| Md33s# | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, surface | Csak O:1 | 8 | MRXC00000000 |

| Md35s | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, alimentary canal | Csak UKN | 8 | MRXD00000000 |

| Md40g | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, alimentary canal | Csak O:2 | 8 | MRXE00000000 |

| Md6g | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, alimentary canal | Csak O:3 | 4 | MRXB00000000 |

| Md70g | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, alimentary canal | Csak O:2 | 4 | MRXG00000000 |

| Anth48g | C. sakazakii | Anthomyiidae spp., alimentary canal | Csak UKN | 221 | MRXF00000000 |

| Md5s | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, surface | Csak O:3 | 4 | MRWZ00000000 |

| Md5g | C. sakazakii | M. domestica, alimentary canal | Csak O:2 | 4 | MRXA00000000 |

| Lc10s | C. sakazakii | Lucilia cuprina, blowfly, surface | Csak O:3 | 4 | NDXD00000000 |

| Lc10g | C. sakazakii | L. cuprina, alimentary canal | Csak O:3 | 4 | NDXE00000000 |

| Ls15g | C. sakazakii | Lucilia sericata, blowfly, alimentary canal | Csak O:1 | 256 | NDXF00000000 |

*All the assemblies along with the PGAP (Haft et al., 2018) annotations were released under FDA GenomeTrakr Bioproject on NCBI (PRJNA258403) and the genomic characteristics can be found in Supplementary Table 1. These isolates were obtained from flies by using the method described by Pava-Ripoll et al. (2012), Pava-Ripoll et al. (2015b). These strains were identified to their Cronobacter species identification using species-specific rpoB and cgcA PCR assays as described by Stoop et al. (2009); Lehner et al. (2012), and Carter et al. (2013). Sequence type designations for each strain were determined by uploading whole genome assemblies or PCR amplicon sequences (Baldwin et al., 2009) to the Cronobacter MLST website (http://pubmlst.org/cronobacter/, last accessed, 5/7/2020) and to the CFSAN GalaxyTrakR tool (https://galaxytrakr.org/, last accessed 5/7/2020) which scans genomes against PUBMLST schemes. UKN means that the serotype was not determined by PCR analysis. #Abbreviations “s” or “g” refer to anatomical fly location that the isolate was obtained from; “s” refers to “surface” and “g” refers to “gut” or the fly’s “alimentary canal.”

Bacterial Strains: Identification and Molecular Characterization

Nineteen Cronobacter fly strains were characterized biochemically and identified according to the classification scheme defined by Iversen et al. (2008) and Joseph et al. (2012a), and their species identities were confirmed using both the rpoB and cgcA species-specific PCR assays as described by Stoop et al. (2009), Lehner et al. (2012), and Carter et al. (2013). Assistance in assigning Cronobacter species identity to these strains was carried out using a Gram-negative card analyzed with the Vitek-2 Compact platform (Biomerieux, Hazelwood, MO, United States). The Vitek-2 Compact instrument’s 5.03 software version was used to taxonomically place these strains into the Cronobacter species complex using a slash-line protocol analogous to that used for the identification of Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., and other enteric Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Identity of the strains as Cronobacter was further carried out by confirming the presence of the 350-bp amplified region of the genus-specific zinc metalloprotease (zpx) gene and finding the presence of species-specific plasmid gene targets and serotyping PCR assays (Kothary et al., 2007; Mullane et al., 2008; Franco et al., 2011a; Jarvis et al., 2011, 2013; Yan et al., 2015a). These strains were compared with strains obtained from clinical, food, and environmental sources which were characterized in previous studies (Franco et al., 2011a; Jarvis et al., 2011, 2013; Yan et al., 2015a,b; Chase et al., 2017; Gopinath et al., 2018; Jang et al., 2018a,b). Multiple locus sequence typing (MLST) of the strains was performed either by submitting genome sequences to the Cronobacter MLST website1 (last accessed 5/7/2020) or by performing the PCR reactions (to amplify the following genes: atpD, fusA, glnS, gltB, gyrB, infB, and pps) for sequencing according to the procedure described by Baldwin et al. (2009). Primer sequences and PCR reaction parameters can be found at the Cronobacter MLST website at https://pubmlst.org/cronobacter/info/protocol.shtml. For these strains, PCR amplicons were first purified using the Qiagen PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Inc. Germantown, MD), and submitted to Macrogen (Rockville, MD, United States) for sequencing. Sequence FASTA files were then uploaded to the Cronobacter MLST website for analysis. All genomes were also submitted to Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition’s (CFSAN’s) Galaxy GenomeTrakr website’s MLST tool (last accessed 5/7/2020) for analysis. Similarily, FASTA formatted genome assemblies were uploaded into CFSAN’s Galaxy GenomeTrakr AMRFinderPlus tool2 (last accessed, 5/7/2020) to scan each genome using a combined protein BLAST and hidden Markov model approach against a high-quality curated antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene reference database which is designed to identify acquired antimicrobial resistance genes in bacterial AMR protein sequences as well as known point mutations for several taxa. More details can be found at https://github.com/ncbi/amr/wiki (last accessed 5/7/2020) (Zankari et al., 2012, 2017; Feldgarden et al., 2019). C. sakazakii strain 505108 co-harbors three plasmids of different incompatibility classes: IncHI2, IncX3, and IncFIB, respectively (Shi et al., 2018). p505108-MDR [National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession #: KY978628] and p505108-NDM (New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1, NCBI accession #: KY978629) FASTA files were downloaded from NCBI and used as the positive control for determining antimicrobial resistance genes in the fly strains. The antibiotics that the CFSAN Galaxy’s AMRFinderPlus tool identifies includes: aminoglycosides; amoxicillin/clavulanate (2:1); ampicillin; chloramphenicol; colistin; cefotaxime; cefoxitin; florfenicol; fusidic acid; gentamicin; macrolides; nitroimidazole; penicillin; quinolone; rifampicin; sulfamethoxazole; spectinomycin; streptomycin; tetracycline; trimethoprim; beta-lactams and extended spectrum beta-lactams (ESBLs), and ceftiofur.

To determine the presence and distribution of γ1a fimbriae among these Cronobacter strains, PCR primers were used. PCR primers shown in Table 2 were designed to target species-specific regions of the γ1a fimbriae chaperon-usher (CU) sequences. For amplification of γ1a CU genes in C universalis, C. dublinensis, C. sakazakii, and C. muytjensii, each species-specific forward PCR primer (γ1a_1215f, γa_1325f, γ1a_1529f, or γ1a_1621f, respectively) was mixed with primer γ1a_1830r. For amplification of the γ1a CU genes in C. turicensis and C. malonaticus, each species-specific reverse primer (γ1a_485r or γ1a_613r, respectively) was mixed with primer γ1a_220f. All primers used in the PCR amplification experiments were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, United States). All PCR mixtures were prepared using the GoTaq Green master mix (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, United States) in a final reaction volume of 25-μl with 1 unit of GoTaq Hotstart DNA polymerase, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate. Primers were added at 1 μM each, along with 1 μl DNA template (approximately 90 ng DNA/25-μl reaction mixture). In all PCRs, the polymerase was activated by using a 3-min incubation step at 94°C, followed by 30-cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing temperature of 65°C for 15 s and an extension step at 72°C for 45 s. For each reaction, a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C completed the reaction cycle.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers and amplicon size for determining presence of γ1a fimbriae gene in Cronobacter species.

| Primer name | Sequence | Amplicon size (bp) | Species targeted |

| γ1a_1215f | TGCGATGGGGGCAGACGCTTA | 616 | C. universalis |

| γ1a_1325f | ACAACACGACCTCTACCGGCCA | 506 | C. dublinensis |

| γ1a_1529f | GTCAGACGCTCGACAGCATGGG | 302 | C. sakazakii |

| γ1a_1621f | GGCTTTGCCTGTACGACATCCGG | 210 | C. muytjensii |

| γ1a_1830r | GTCATCCATCAGSGTGCCGCT | C. muytjensii-sakazakii-dublinensis-universalis | |

| γ1a_485r | CGCCTGCGGGATGCTTACCT | 266 | C. turicensis |

| γ1a_613r | GCGAGGAGTCCCCCTCACCT | 394 | C. malonaticus |

| γ1a_220f | GGCAACTACCCGCTGCGCAT | C. turicensis- malonaticus |

Preparation of Genomic DNA

All strains were grown overnight in a shaker incubator (160 rpm) at 37°C in 5 ml of Trypticase soy broth (BBL, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) supplemented with 1% NaCl (final conc.). Genomic DNA was isolated from 2 ml of the culture with the robotic QIAcube workstation and its automated Qiagen DNeasy technology (QIAGEN Sciences, Germantown, MD, United States) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Generally, 5–50 μg of purified genomic DNA was recovered in a final elution volume of 200 μl and used as a DNA template for PCR analysis. For microarray analysis, the purified DNA was then further concentrated using an Amicon Ultracel-30 membrane filter (30,000 molecular weight cutoff, 0.5 ml, Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, United States) to a final volume of 10–25 μl as described by Tall et al. (2015).

Microarray Design and Hybridization

The microarray used in this study is an Affymetrix MyGeneChip Custom Array (Affymetrix design number: FDACRONOa520845F) which utilizes the whole genome sequences of 15 Cronobacter strains, as well as 18 plasmids as described by Tall et al. (2015). Each gene (19,287 Cronobacter gene targets) was represented on the array by 22 unique 25-mer oligonucleotide probes, as described by Jackson et al. (2011) and Tall et al. (2015). Genomic DNA from Cronobacter and phylogenetically related species as listed in Supplementary Table 7 was hybridized, washed in the Affymetrix FS-450 fluidics station, and scanned on the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 (AGCC software) as described by Jackson et al. (2011) and as modified by Tall et al. (2015). All reagents for hybridization, staining and washing were made in conjunction with the Affymetrix GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual.

Microarray Data Analysis, Calculating Gene Differences, and Generating Dendrograms

For each gene represented on the microarray, probe set intensities were summarized using the Robust MultiArray Averaging (RMA) function in the Affymetrix package of R-Bioconductor as described by Bolstad et al. (2003). RMA summarization, normalization, and polishing was done on the data and final probe set values were determined as explained by Jackson et al. (2011) and as modified by Tall et al. (2015). Gene differences were determined and phylogenetic trees were created using the SplitsTree 4 neighbor net joining method (Jackson et al., 2011; Tall et al., 2015). In a similar fashion, the distribution and prevalence of fimbriae genes were also determined using just fimbriae alleles which are captured on the FDA Cronobacter microarray and these alleles are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Whole Genome Sequencing and Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of the Cronobacter filth fly strains was performed using the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) with a Nextera XT library kit. Trimmed Fastq data sets were trimmed and de novo assembled with CLC Genomics Workbench version 9.0 (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark) as described by Grim et al. (2015) and Chase et al. (2016). All assemblies, along with the PGAP annotations (Haft et al., 2018), were released under FDA GenomeTrakr Bioproject on NCBI (PRJNA258403) which is part of FDA’s foodborne pathogen research umbrella project at NCBI (PRJNA186875). Genomic information regarding the strains are shown in Supplementary Table 1 which also includes genome accession numbers.

Genome Sequence Annotation and Analysis

Genomes were annotated initially by using the SEED server (Overbeek et al., 2014) for developing this manuscript. A new core genome analysis workflow was developed using Spine software (Ozer et al., 2014). Briefly, filth fly and representative Cronobacter species genomes in FASTA format and their respective annotations in Genbank format were downloaded from NCBI. The server running at http://vfsmspineagent.fsm.northwestern.edu/cgi-bin/spine.cgi (last accessed 5/7/2020) was used for the analysis. A series of homology parameters were used to titer optimal configurations and are available upon request. The C. condimenti genome was defined as an outlier due to its genomic distance from the other Cronobacter species (Grim et al., 2013). C. sakazakii BAA-894 coding genes were used as the top-level reference for the analysis. The final Spine-derived ‘backbone sequences’ were designated as the ‘whole genome core-genes’ for studying phylogenetic relationship among fly isolates belonging to different Cronobacter species. NCBI standalone BLAST database suite was used for finding homologs. Briefly, a BLAST database of the filth fly strain genomes was created. Nucleotide sequences of putative virulence-associated protein coding gene loci from C. sakazakii BAA-894 was used to query this database. In-house Perl and Python scripts were used to process the data files (a default 90% nucleotide identity was used). Filth fly Cronobacter strain data sets were uploaded to the PHASTER (Phage Search Tool Enhanced Release) web server and pipeline3 (last accessed 5/7/2020) for phage sequence identifications (Zhou et al., 2011; Arndt et al., 2016).

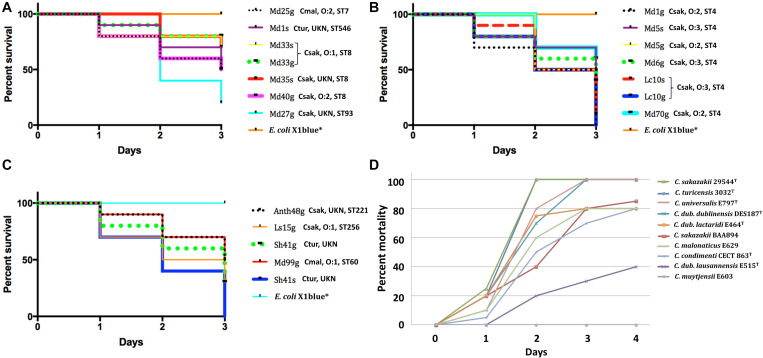

Zebrafish Infection Studies

To understand the virulence of these filth fly strains compared to other strains including those of clinical origins, zebrafish infection studies were performed. Husbandry, breeding and microinjection of approximately 50 CFU of bacteria into the yolk sac of 2 days post fertilization albino zebrafish (Danio rerio) was maintained following the original procedure described in the study by Fehr et al. (2015) and as updated by Eshwar et al. (2016). Virulence was assessed by determination of the survival rate (30 embryos: 10 embryos per bacterial strain, three independent experiments) over 72 hpi (=3 dpi). The number of dead embryos was determined visually based on the absence of heartbeat. Zebrafish husbandry and manipulation were conducted with approval (Licence Number 150) from the Veterinary Office, Public Health Department, Canton of Zurich (Switzerland). For experiments with zebrafish embryos and larvae ≤5 days post fertilization (dpf), no approval for animal experimentation is required according to the Swiss animal experimentation law. For statistical analysis, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and statistics [Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test] for zebrafish embryos infection experiments was performed with GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, CA, United States). One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD tests were used to assess the statistical significance.

Results and Discussion

Identification and AMR Characterization of Cronobacter Species Isolated From Filth Flies

During the surveillance study reported by Pava-Ripoll et al. (2012), 19 Cronobacter strains were obtained from filth flies from four fly species belonging to the families Muscidae, Calliphoridae, Sarcophagidae, and Anthomyiidae (one fly was identified only to the family level). Results are shown in Table 1. Two C. malonaticus, three C. turicensis and 14 C. sakazakii were identified from the alimentary canals and external surfaces of the filth flies. Interestingly, on five occasions, Cronobacter strains were isolated from both the alimentary canal (strain name labeled with suffix “g”) and the external body surface (strain name labeled with suffix “s”) of the same fly. In three of these instances, a fly was found that carried the same Cronobacter species at both anatomical sites: a red-tailed flesh fly carried C. turicensis serogroup unknown, ST569 strains (Sh41g and Sh41s), a house fly carried C. sakazakii serogroup O:1, ST8 strains (Md33g and Md33s), and a blowfly carried C. sakazakii serogroup O:3, ST4 strains (Lc10s and Lc10g). Another housefly carried a mixture of C. sakazakii ST4 strains differing only by serogroup designation: on its surface a C. sakazakii serogroup O:3 (Md5s), and in its alimentary canal a C. sakazakii serogroup O:2 strain (Md5g). Lastly, a C. turicensis ST546 strain (Md1sN, CturO:Unknown) was obtained from the body surface of another housefly and Md1g, a C. sakazakii serogroup O:2, ST4 strain was obtained from its alimentary canal. Two other houseflies carried C. malonaticus ST60 and ST7 strains (Md99g and Md25g, serogroups Cmal O:1 and Cmal O:2, respectively) in their alimentary canals. In addition to the C. malonaticus, C. turicensis, and C. sakazakii strains described above, there were seven other C. sakazakii isolated from filth flies that were identified as a ST93 C. sakazakii serogroup unknown (Md27gN), and two C. sakazakii ST8: one (Md35s) possessing serogroup CsakO:Unknown and the other (Md40g) possessed a CsakO:2 serogroup determinants. Additional C. sakazakii strains were found associated with these flies and include two ST4 C. sakazakii strains: (Md6g, Md70g), a ST221 strain (Ath48g), and a ST256 (Ls15g) possessing CsakO:3, CsakO:2, CsakO:Unknown, and CsakO:1 serogroup determinants, respectively. Taken together, MLST analysis of these Cronobacter strains (shown in Table 1) demonstrated that there were nine different STs found among the filth fly strains.

FASTA formatted files of plasmids p505108-multidrug resistant (MDR, NCBI accession #: KY978628.1) and p505108-NDM (New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase 1, NCBI accession #: KY978629.1) reported by Shi et al. (2018) were downloaded from NCBI. The corresponding C. sakazakii 505108 (ST1) sequences were used as positive control sequences, for comparison with the filth fly strains using the CFSAN AMRFinderPlus tool. The blaCSA/CMA family of class C β-lactamase resistance genes described earlier by Müller et al. (2014) was possessed by all strains. This family of β-lactamases (AmpC) are non-inducible and are considered to be cephalosporinases. The results of this analysis are shown in Supplementary Table 2 and demonstrate that the C. turicensis and the C. malonaticus carried a C. malonaticus (CMA) class C blaCMA resistance gene and that the filth fly C. sakazakii carried a C. sakazakii CSA class C blaCSA resistance gene. Six of these CSA class C bla resistance genes were only identified to the family level whereas the remainding class C bla resistance genes were identified as either CSA-2 or CSA-1 variants. Additionally, the three C. turicensis strains, MD1sN, Sh41s, and Sh41g also possessed a fosA family fosfomycin resistance glutathione transferase gene. In contrast, CFSAN’s Galaxy’s AMRFinderPlus tool correctly identified all antimicrobial resistence/tolerance genes present on p505108-MDR (KY978628) which included the following antimicrobial resistance/tolerance genes: blaTEM–1, dfrA19, aph(3′′)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, mcr-9.1, aph(3′)-Ia, catA2, tet(D), aac(6′)-Ib3, blaSHV–12, sul1, blaDHA–1, qnrB4, qacEdelta1, arr, aac(3)-II, and aac(6′)-IIc with predicted resistances/tolerances to β-Lactam based compounds, Trimethoprim, Aminoglycoside, Colistin, Phenicol, Tetracycline, Sulfonamide, Quinolone, Quaternary Ammonium, and Rifamycin antibiotics, respectively. The antimicrobial resistance genes found on plasmid p505108-NDM (KY978629) were identified as ble, blaNDM–1, and blaSHV–12 with predicted resistances to bleomycin and NDM-1 β-Lactam antibiotics, consistent with previously results reported by Shi et al. (2018).

Characterization of RepFIB Plasmids and pESA3- and pCTU1-Specific Gene Targets Among the Filth Fly Strains Compared to Other Cronobacter Strains

The common Cronobacter virulence plasmids, pESA3, CSK29544_1p, pCS2, pGW2, p1CFSAN068773, pSP291-1, pCMA1, p1, and pCTU1 share a high degree of sequence homology (Kucerova et al., 2010; Franco et al., 2011a; Stephan et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2013; Moine et al., 2016). Previously identified backbone genes or gene clusters which are known to be associated with these plasmids include a common incompatibility class IncF1B replicon (repA) and two iron (III) acquisition systems, eitCBAD (ABC heme transporter) and iucABCD/iutA (Cronobactin, a hydroxamate-type, aerobactin-like siderophore and the only known siderophore possessed by Cronobacter). Targeting of the shared repA gene and the two iron acquisition system gene clusters (eitA and iucC genes representing each gene cluster) by PCR showed that all 19 fly strains possessed repA, eitA, and iucC genes suggesting that the common virulence plasmids (pESA3-like, pCMA1-like or pCTU1-like) were possessed by these strains (Table 3). Furthermore, PCR analysis of these strains showed that 10 of the C. sakazakii were PCR-positive for the plasmid-borne Omptin-like protease, Cronobacter plasminogen activator gene (cpa), and four of these C. sakazakii strains were PCR-negative. The fly C. malonaticus and C. turicensis strains were also PCR-negative for this gene (Table 3). Franco et al. (2011b) showed that Cpa had significant identity to proteases belonging to the Pla subfamily of omptins such as PgtE which is expressed by Salmonella enterica, Pla of Yersinia pestis, and PlaA of Erwinia spp. They further showed that the proteolytic activity of Cpa allows for degradation of several host serum proteins, including circulating complement components, C3, C3a, and C4b. With degradation of these complement components by Cpa, it is thought that systemic circulating Cronobacter cells would then be protected from complement-dependent serum killing. Expression of Cpa was also found by Franco et al. (2011b) to inactivate the serum protein, plasmin inhibitor α2-antiplasmin (α2-AP) which leads to an unrestrained conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, further promoting systemic spread of these bacteria. Interestingly, C. malonaticus, C. turicensis, and all of the cpa-negative C. sakazakii (including Md33s, Md33g, Md35S, and Md40g) also lacked the conserved flanking regions surrounding cpa (Table 3). Interestingly, the cpa-PCR negative C. sakazakii strains were identified as ST8 strains (Table 1). Results showing that these cpa-PCR negative strains were also PCR-negative for the flanking regions (Δcpa) strongly suggests that cpa is absent and the lack of amplification is not due to sequence variation that may have been associated with the PCR primer regions of cpa. Notably, Almajed and Forsythe (2016) reported similar findings for a ST8 clinical strain (C. sakazakii strain 680) isolated from an unknown cerebral spinal fluid sample from the United States, and these authors also reported that this strain was rapidly eliminated when incubated with human serum, despite possessing the plasmid. Additional representatives of C. sakazakii ST8 should be analyzed so as to determine whether or not this particular ST (and other related STs) has the propensity to be cpa-negative. Further research is also needed in order to better understand the molecular mechanisms of cpa expression in Cronobacter.

TABLE 3.

Plasmidotype patterns* observed for the 19 Cronobacter strains isolated from filth fly.

| Isolate | Species ID | pESA3/pCTU1 (incFIB) | eitA | iucC | cpa | Δ cpa | Δ T6SS | T6SS IntL | vgrG | T6SS R end | T6SS IntR | Δ fha | fhaB | dfha | pESA2/pCTU2 (incF2) | pCTU3 (incH1) |

| Md25g | malonaticus | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) |

| Md99g | malonaticus | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Sh41g | turicensis | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Sh41s | turicensis | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Md1sN | turicensis | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Md1g | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Md5s | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Md5g | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Md6g | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Lc10s | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Lc10g | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Ls15g | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Md27gN | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) |

| Md33s | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | ND# | ND |

| Md33g | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Md35s | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Md40g | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

| Anth48g | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) |

| Md70g | sakazakii | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

*Results show whether the strains are PCR-positive or -negative using primers and PCR reaction parameters described by Franco et al. (2011a). #ND is an abbreviation for Not Determined.

Also shown in Table 3 are the findings that all C. malonaticus and C. turicensis strains did not possess the T6SS gene cluster (ΔT6SS PCR-positive). Except for a single C. turicensis strain (Sh41s) which was PCR-positive for vgrG, C. malonaticus and C. turicensis strains also lacked, as expected, all T6SS gene cluster genes. Interestingly, four C. sakazakii ST8 strains (Md33s, Md33g, Md35g, and Md40g) also lacked the entire T6SS gene cluster. Interestingly, other C. sakazakii T6SS PCR-positive strains (e.g., Lc15g, Md27gN, and Anth48g) possessed most of the gene cluster (gene targets: T6SSIntL, vgrG, and T6SSRend). However, none of the filth fly C. sakazakii strains were PCR-positive for the T6SSIntR gene region. Taken together these results add support to the hypothesis that the plasmid-borne T6SS in C. sakazakii is in a state of “genetic flux” as posited by both Franco et al. (2011a) and Yan et al. (2015b). Recently, Wang et al. (2018) showed evidence of more than one T6SS gene cluster in C. sakazakii strain ATCC12868 that they denoted as T6SS-1 and T6SS-2. Their results suggest that T6SS-1 may contribute to interbacterial competition processes which may allow C. sakazakii to better compete with other species and the second gene cluster (T6SS-2) may be important during host interaction. They also proposed that the “genetic flux” seen in T6SS-2 gene cluster may lead to greater levels of systemic spread. However, why C. sakazakii strain ATCC12868 has multiple T6SS gene clusters contained within both the chromosome and plasmid pESA3 remains to be elucidated. Together, these results suggest that C. sakazakii may use these T6SS systems to quickly adapt to whatever stressful environment the bacterium encounters, e.g., environment versus host.

Lastly, the C. malonaticus and C. turicensis strains, as well as two of the C. sakazakii strains (Md27gN and Anth48g) possessed the filamentous hemagglutinin gene cluster as represented by the presence of fhaB (Table 3). The fhaB-positive C. sakazakii strains belonged to ST93 and ST221 (Table 1). According to the Cronobacter pubMLST site, both ST93 and ST221 are notably rare among sequence types described earlier for C. sakazakii. The finding that these strains possess fhaB is not surprising since Franco et al. (2011a) have previously reported that approximately 20% of C. sakazakii strains may possess fhaB. A comparison of the filth fly strain’s plasmidotyping results with that of other non-fly strains (data not shown) confirmed similar trends which were also observed previously by Franco et al. (2011a), and illustrate that no new plasmidotyping trends were identified at this time (Tall et al., 2019; Jang et al., 2020). Jang et al. (2018b) also investigated the prevalence and distribution of plasmid pESA3 genes associated with the virulence plasmids including pESA2 and pCTU3 harbored by 26 spice-associated C. sakazakii. They found that all of the strains possessed eitA, iucC, cpa, and the T6SS allele IntL but few possessed the rest of the T6SS gene cluster and six strains possessed the fhaB gene. However, it is interesting to speculate why certain C. sakazakii may possess this adhesin with such a high sequence homology to the filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) of Bordetella pertussis (Franco et al., 2011a). Currently, it is not known if FHA is responsible for adaptive colonization of the upper respiratory tract and if it contributes to pneumonia cases such as those highlighted by Gosney et al. (2006), Patrick et al. (2014), and Alsonosi et al. (2015). This question remains to be explored and further research is needed to better understand the functional role of fhaB in Cronobacter.

To determine the presence of plasmids pESA2/pCTU2 and pCTU3 carried by the fly strains, we performed PCR analysis with these strains using pESA2/pCTU2-specific primers as described by Franco et al. (2011a). The results showed that none of the strains (only 18 strains tested in this study) possessed the conjugative pEAS2/pCTU2-like plasmids. Interestingly, C. malonaticus strain Md25g, 11 of the 19 C. sakazakii and all C. turicensis strains possessed the pCTU3-like plasmid (Table 3). pCTU3-like plasmid was originally described in C. turicensis by Stephan et al. (2011). These authors showed that this plasmid harbored genes responsible for arsenic and copper resistance, as well as silver ion transport. It is interesting to speculate as to why such fly strains possess a plasmid which harbors genes involved in heavy metal resistance via membrane-associated efflux transporters (Zhongyi et al., 2017; Negrete et al., 2019). The low prevalence of these plasmids is similar to that described recently by Tall et al. (2019) who had reported that pCTU3-like plasmids are found more often in Cronobacter than conjugative pCTU2/pESA2-like plasmids. It is currently unknown if flies benefit from having a population of bacteria living within their gut microflora which can express a heavy metal resistance phenotype or if maintaining such related genes or gene clusters has a role in heavy metal resistence in agriculture settings as suggested by Zhongyi et al. (2017). Interestingly, C. sakazakii ingested by adult houseflies was demonstrated to be transmitted to the fly progeny by Pava-Ripoll et al. (2015a), possibly by evolving several unknown mechanisms to evade the fly’s immune system. However, health benefits to filth flies provided by colonization of C. sakazakii still needs to be further studied.

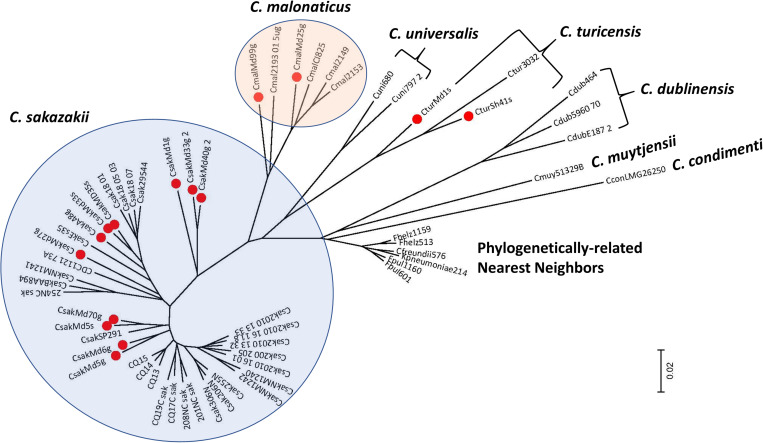

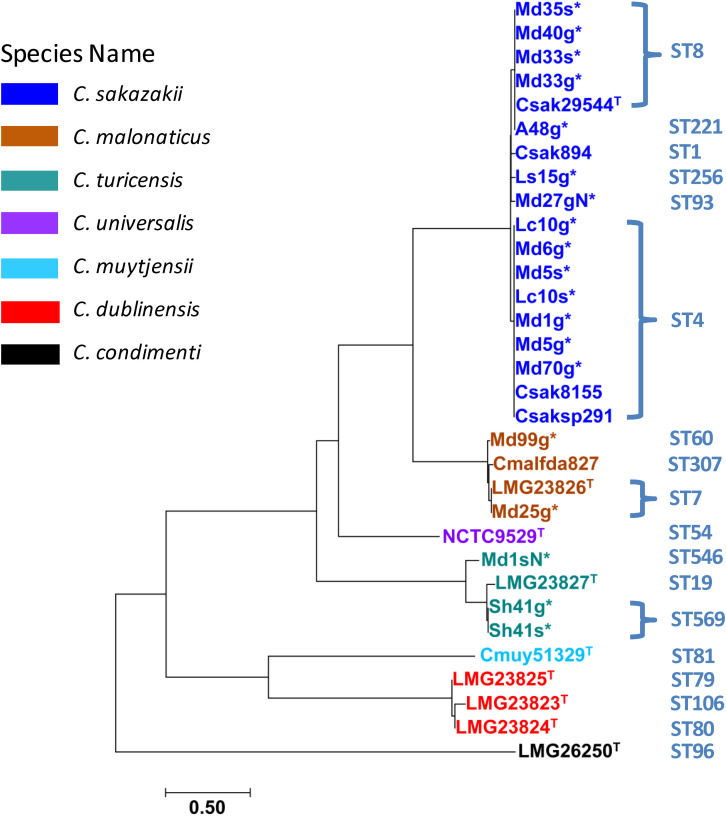

Pan Genomic Microarray Analysis Clustered the Fly Strains as Separate Species According to Sequence Type

To understand the phylogenetic relationship among the filth fly strains, DNA microarray hybridization experiments with 15 of the 19 strains were performed. Results were compared with other phylogenetically-related Cronobacter strains representing the seven Cronobacter species and nearest phlyogenetically-related taxa as listed in Supplementary Table 7. Take note that not all strains were tested by microarray analysis due to the cost of the each array. After applying the RMA-derived presence/absence gene algorithm, a gene-difference matrix was generated from the interrogation of these strains. From these data, as illustrated in Figure 1, a phylogenetic tree was generated which demonstrates that the microarray could accurately identify the filth fly strains to the correct Cronobacter species taxon. The filth fly strains grouped, as expected, with each of the three species clusters identified as C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus, and C. turicensis. As expected, the phylogenetic tree possessed a similar bidirectional genomic clustering characteristic to that previously described by Grim et al. (2013), Jackson et al. (2015), Killer et al. (2015), Tall et al. (2015), Chase et al. (2017), and Jang et al. (2018b) for other similar Cronobacter strains. An absolute correlation was found between the species identity of each filth fly strain analyzed by MA and that obtained by the validated end-point species-specific rpoB and cgcA PCR assays. Lastly and as expected, the C. dublinensis cluster was comprised of three separate clades which represented the three subspecies of C. dublinensis subsp: dublinensis, lactaridi, and lausannensis. Since only one strain of C. muytjensii, C. universalis, and C. condimenti was used in this analysis, these strains formed single species-strain clades which clustered separately. The lone C. condimenti strain was a distant outlier.

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic analysis among 15 fly Cronobacter strains (identified with a red dot) and 45 other Cronobacter and phylogenetically-related strains was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method using the 19,287 Cronobacter gene targets (Saitou and Nei, 1987) of the FDACRONOa520845F microarray. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 1.86949337 is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the p-distance method (Nei and Kumar, 2000) and are in the units of the number of base differences per site. The analysis involved 60 strains evaluated by using the FDA Cronobacter microarray. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 21,402 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016). These Cronobacter and phylogenetically related strains were analyzed from the presence-absence gene matrix (data not shown). The microarray experimental protocol as described by Jackson et al. (2011) and as modified by Tall et al. (2015) was used for the interrogation of the strains for this analysis. The phylogenetic tree illustrates that the Cronobacter microarray could clearly separate the seven species of Cronobacter with each species forming their own distinct cluster, and that representative fly strains clustered (identified with red dots) according to their species taxon. The scale bar represents a 0.02 base substitution per site.

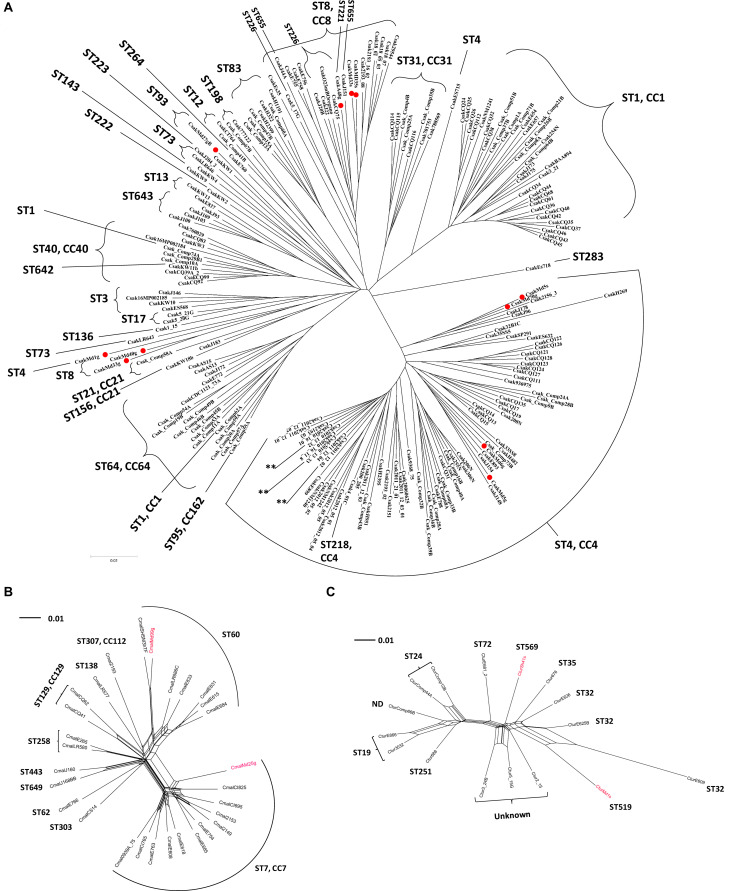

Figure 2A shows a phylogenetic tree developed for 11 filth fly C. sakazakii (red dots) in comparison with 195 other C. sakazakii strains. This figure represents a phylogenetic tree that was developed using microarray results and then overlaid with ST designations which were obtained using the seven allele MLST scheme as described by Baldwin et al. (2009) and CFSAN’s Galaxy MLST tool. As expected, the eleven C. sakazakii filth fly strains clustered according to ST designations. C. sakazakii strains Md33g and Md35g grouped together with other ST8 C. sakazakii strains [ST8, clonal complex (CC) 8 MLST profile: atpD 11, fusA 8, glnS 7, gltB 5, gyrB 8, infB 15, and pps 10] and filth fly strain Anth48g (ST221) also clustered close to these C. sakazakii ST8 strains, and as mentioned, C. sakazakii ST221 is a rare sequence type found in the Cronobacter MLST database. There is only one other strain (ID: 605; isolate name: CSWHPU-20; alias CY20) found in the database that possesses this ST designation (ST221 MLST profile: atpD 1, fusA 78, glnS 7, gltB 5, gyrB 8, infB 106, and pps 138), and which was isolated in 2013 in China from an infant noodle sample. To date and according to the Cronobacter MLST website, C. sakazakii strains possessing ST8, 111, 124 130, 133, 226, 279, 442, 608, 655 are members of the CC8 group. Interestingly, C. sakazakii Anth48g matches four of the seven alleles, but differs from these other ST8 strains by possessing the MLST alleles, fusA 78, infB 106, and pps 138, suggesting that ST221 strains may be related to ST8 strains and should to be considered as a member of C. sakazakii CC8 group. Interestingly, strain Md27gN which is a ST93 strain (ST93 MLST profile: atpD 15, fusA 1, glnS 3, gltB 32, gyrB 5, infB 36, and pps 190) clusters with another ST93 strain from the Republic of Korea. C. sakazakii filth fly strain Md1g (ST4), and ST8 strains Md40g and Md6g clustered together outside the main ST8 and ST4 clusters. Other strains which clustered outside their main ST clusters included ST1 strains Comp62A and Comp74A, and ST73 strain LR643. In summary, these results show that there is a good correlation between the seven allele sequence typing scheme and that obtained by MA. However, there were a few instances where the phylogenomic analysis based on the ∼19,000 Cronobacter genes gave a greater power of resolution when compared to the original seven allele MLST scheme. These results support that found in other studies as well (Chase et al., 2016; Gopinath et al., 2018; Jang et al., 2020).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Phylogenetic Neighbor net (SplitsTree4) analysis of representatives of C. sakazakii showing a bi-directional nature (along the tree X-axis). (B) Phylogenetic Neighbor net (SplitsTree4) analysis of representatives of C. malonaticus. The tree was generated from the gene-difference matrix (data not shown). (C) Phylogenetic Neighbor net (SplitsTree4) analysis of representatives of C. turicensis showing a bi-directional nature (along the tree X-axis). The tree was generated from the gene-difference matrix (data not shown). The microarray experimental protocol as described by Jackson et al. (2011) and as modified by Tall et al. (2015) was used for the interrogation of the strains for the analysis. The phylogenetic trees illustrate that the Cronobacter microarray could clearly separate these Cronobacter strains into distinct clusters based on ST phylogeny. Fly strains are identified by a red dot or red font. The scale bar represents a 0.01 base substitution per site. ND denotes not determined.

Several points can be made regarding these findings using this combinatorial analysis approach. C. sakazakii filth fly strains [Md33s (ST8), Md35s (ST8), Anth48g (ST221), Md5g (ST4), Md5s (ST4), and Md70g (ST4)] grouped among strains of known corresponding ST and CC designations such as CC4 and 8, and these clusters were comprised of both clinically-relevant and PIF-associated strains. These results also suggest that filth fly ST4 and ST8 strains share genomic backbones similar to that of known clinical and food isolates of these respective STs (Joseph and Forsythe, 2011; Joseph et al., 2012b). For example, filth fly strains ST4 Md5g and Md70g clustered with two Jordanian strains cultured from spices, a clinical United States strain 2156 and strain H269, a PIF isolate from Switzerland. This combinatorial analysis approach also highlighted phylogenetic relatedness among groups of C. sakazakii strains with clonal complexes and ST designations that previously had not been recognized. For example, MA was able to show the phylogenetic relatedness among strains of several STs, e.g., ST8 strains clustering with strains of ST83, and ST1 strains clustering with ST31 strains, and ST13 strains clustering with strains of ST643 to name a few. However, at this point, caution is advised because of the small number of strains analyzed.

As shown in Figure 2B, the two C. malonaticus filth fly strains (red font) grouped among C. malonaticus strains possessing ST7 and ST60 which are known C. malonaticus sequence types of clinical importance. Filth fly strain Md25g clustered within the ST7/CC7 clade signifying that a close phylogenetic relatedness existed between this filth fly strain and other ST7/CC7 strains – many of which are from clinical sources – including the C. malonaticus type strain LMG 23826T which was isolated from an adult with a breast abscess. The other filth fly strain, Md99g, clustered with ST60 C. malonaticus food associated and environmental strains.

A similar trend was also observed for the C. turicensis filth fly strains as shown in Figure 2C. The C. turicensis filth fly strains Md1sN and Sh41s (red font) were identified as an ST519 and ST569, respectively. Strain Sh41s (ST569) grouped as a singleton phylogenetically related to strains possessing ST designations of ST72 and ST35. Strain Md1sN grouped with three ST32 strains.

Taken together, this combinatorial phylogenetic analysis provides evidence that related strains from filth flies possess similar gene contents to that of strains from clinical, PIF, other foods, and man-made environmental sources, and that these pathotypes continue to circulate among the United States and European populations, environments, and filth flies. These results also suggest that there may be specific phylogenetically-related pathotypes which are circulating among Cronobacter populations that are not necessarily geographically distinct. This could very well be due to the present day global nature of the food supply. Such results argue for the need for greater vigilance of global food safety controls for the presence of these bacterial pathogens and their vector-associated fifth flies, and further comparative genomic investigations are warranted to understand these complex phylogenomic relationships. Finally, these data also further support the hypothesis that filth flies can serve as vectors of Cronobacter disease transmission.

Presence of Fimbriae-Encoding Genes and Gene Clusters

Bacteria express filamentous assemblies of protein subunits on their exterior surfaces called adherence factors, pili or fimbriae which are used to colonize a host cell membrane surface or serve as conduits for the secretion of substrates, e.g., T4SS fimbriae. It is generally considered that bacterial adherence to an epithelial cell surface is the first step in pathogenesis (Finlay and Falkow, 1989). Adherence occurs either with the main structural fimbrial subunit or with associated fimbrial adhesins and are often target tissue specific. The genetic loci coding for these bacterial structures are found both on the chromosome and on plasmids (Thanassi et al., 2012).

Grim et al. (2013) identified eight fimbrial types among the seven Cronobacter species which was based on the chaperone-usher classification system described by Humphries et al. (2001). Grim et al. (2013) categorized these into a number of genomic regions (GR) encoding for γ1-fimbriae (in GR126 and GR82), genes for γ4-fimbriae (in GR52 and GR6), for κ-fimbriae (in GR112), β-fimbriae (in GR76), curli (in GR55), π-fimbriae (in GR9), and P-pilus homologs (in GR9, but missing in C. sakazakii strain BAA-894). Interestingly, these fimbriae types are also differentially dispersed among the Cronobacter genomes.

Some Cronobacter genomes also harbored curli biosynthesis genes, which are homologous to the curli of Escherichia coli and thin-aggregative fimbriae of Salmonella (Stephan et al., 2011; Hu, 2018). Curli fimbriae belong to a type of highly aggregated surface protein fibers (6–8 nm in diameter and 1 μm in length) classified as amyloids and are involved in adherence to cell or material surfaces, cell-cell aggregation, and biofilm development. The biosynthesis of curli is encoded by two operons, csgBAC and csgDEFG (csg, curli-specific genes in E. coli). Hu (2018), using primers designed to detect the structural curlin subunit gene (csgA) and a putative assembly factor gene (csgG), found that csgA could be identified in C. dublinensis, C. malonaticus, C. turicensis, and C. universalis, but not in C. sakazakii and C. muytjensii. Using the PATRIC tool (Wattam et al., 2017) and NCBI’s genome protein tables, the prevalence and distribution of type 1, β, Σ, Pap, and curli gene clusters possessed by the seven Cronobacter species were summarized by Jang et al. (2020). These authors presented evidence that curli biosynthesis genes are not found in C. sakazakii and C. muytjensii.

The FDA Cronobacter microarray contains probe sets representing fimbriae- or adhesin-related genes which were identified in genome regions (GR) described by Grim et al. (2013). β-fimbriae genes are represented on the microarray as 13 C. sakazakii genes that came from C. sakazakii strains Es15 (NCBI accession ID GCA_000263215) and BAA-894 (NCBI accession ID GCA_000017665) including seven genes of different β-fimbriae probable major orthologous subunits (corresponding to BAA-894 loci: ESA_03512, ESA_03513 and loci ESA_03517 to ESA_03521). The genes for the β-fimbriae chaperone and usher proteins correspond to BAA-894 loci ESA_03516 and ESA_03515. There are also seven β-fimbriae associated genes on the microarray from C. dublinensis subspecies lactaridi, but will not be discussed further because there was no cross hybridization with the filth fly strain samples probably due to the low protein percent sequence similarity (48.6–73.0%) with that of BAA-894. Interestingly and as shown in Supplementary Table 3, of the 13 genes representing β-fimbriae associated with C. sakazakii, C. sakazakii filth fly strain Md27gN hybridized with the β-fimbriae allele from C. sakazakii Es15 (Csak ES15.3466 corresponding to BAA-894 loci ESA_03512, ABU787727), and did not hybridize with the other six genes shared by C. sakazakii strain BAA-894. In contrast, all of the other C. sakazakii filth fly strains hybridized with the β-fimbriae probeset genes shared by C. sakazakii strain BAA-894 and did not hybridize with the β-fimbriae gene from C. sakazakii Es15. These results suggest that the filth fly C. sakazakii do possess β-fimbriae genes and that there are multiple β-fimbriae orthologous major subunit genes present in C. sakazakii genomes. All of the filth fly C. sakazakii hybridized with the β-fimbriae usher protein, ESA_03515 (ABU78730) and the β-fimbriae chaperone protein, ESA_03516 (ABU78731). As expected, the C. malonaticus and C. turicensis fly strains did not hybridize with these C. sakazakii genes.

A similar observation was also observed for genes representating type 1 fimbriae (Supplementary Table 3). Genes representing type 1 fimbriae-related genes on the microarray are from three C. sakazakii strains (BAA-894, 2151, and Es35), C. malonaticus LMG 23826T and C. turicensis LMG 23827T. They are annotated as anchoring protein FimD (five fimD C. sakazakii orthologous genes ESA_02540, ESA_02343, ESA_01974, ESA_02797, and ESA_04071); fimbrial adaptor subunit FimG (ESA_02795 and ESA_02542; fimbrial adhesin precursor, ESA_02541; and chaperone protein FimC precursor, ESA_04072). Other type 1 fimbriae genes that are captured on the array include five fimD C. sakazakii orthologous genes (ESA_04071, ESA_02540, ESA_02343, ESA_01974, and ESA_02797), four C. malonaticus fimD genes (ESA_02343, ESA_02540, and ESA_04071), and three C. turicensis fimD genes (ESA_02343, ESA_02540, and ESA_04071). Also as expected, the microarray captured type 1 fimbrial genes from C. condimenti, C. universalis, C. dublinensis and C. muytjensii and that did not cross hybridize with any of the filth fly C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus, and C. turicensis strains.

Σ-fimbriae related genes are represented on the microarray by two genes from C. sakazakii strain BAA-894 (Σ-fimbriae chaperone protein, ESA_01345 and Σ-fimbriae tip adhesin, ESA_01347), two orthologs from C. malonaticus (Σ-fimbriae chaperone protein, ESA_01345 and Σ-fimbriae tip adhesin, ESA_01347), and three orthologs each from C. turicensis (Σ-fimbriae chaperone protein, ESA_01345; Σ-fimbriae usher protein, ESA_01346; and Σ-fimbriae tip adhesin, ESA_01347), and two copies of a Σ-fimbriae uncharacterized paralogous subunit, ESA_01344 and ESA_01343. Only filth fly C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus, and C. turicensis strains hybridized with each of the species-specific Σ- fimbriae genes. As expected, genes from the other Cronobacter species did not hybridize with these probes (Supplementary Table 3).

Genes for curli specific genes (csg) that are captured on the microarray are derived from C. condimenti, C. dublinensis, and C. turicensis (Supplementary Table 3). Additionally, there are several orthologs of a curlin transcriptional activator gene from C. sakazakii Es15 and C. muytjensii 51329T (both ESA_03113). Eight of the filth fly C. sakazakii strains and C. turicensis strain Sh41g cross hybridized with this transcriptional activator gene from C. sakazakii Es15 and filth fly strains C. turicensis Md1sN and Sh41s hybridized with the transcriptional activator gene from C. turicensis. Other curli genes from C. turicensis z3032 include genes for curli assembly/transport (csgG, csgE, and cggF), for nucleation (csgB), the major curlin subunit (csgA), and a gene for a putative curli production protein (csgC). The two C. malonaticus fly strains did hybridize with csgG, csgE, csgA, but not csgB suggesting that these strains can secrete the curlin structural monomer, but may not nucleate the protein. All three fly C. turicensis strains did not hybridize with any of the curli assembly, nucleation, or subunit genes. These findings were corroborated by BLAST analysis of the WGS assemblies.

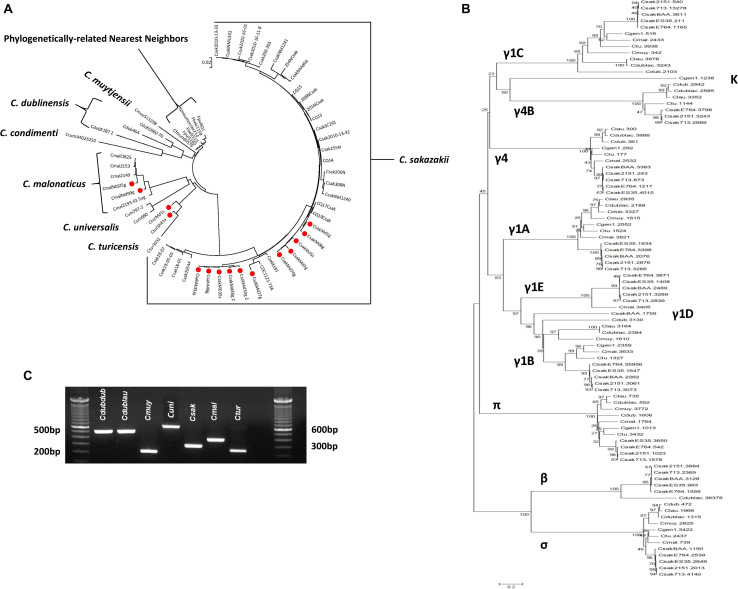

Figure 3A shows the relationship among the filth fly strains which were analyzed with the microarray and the identities of various fimbriae gene clusters among the strains. The Cronobacter microarray contains 51 different usher-chaperone genes from all seven species and some species possessed genes of more than one fimbriae class. Interestingly, each Cronobacter species possessed species-specific fimbriae gene orthologs such that phylogenetically, MA using just fimbriae genes alone showed that each of the filth fly species clustered according to respective species groups. This analysis was extended to 242 Cronobacter strains and is shown in Figure 3B where a similar species-specific phylogeny trend was observed. Together, these results suggest that each Cronobacter species may possess common fimbrial orthologs and that the fimbriae sequence divergence has evolved along species lines. These findings are also supported by examining Supplementary Table 3 which shows the hybridization results (presence or absence) for fimbriae genes from C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus, and C. turicensis which are captured on the microarray. This analysis also illustrates that some of the probes cross hybridized among all three species with the pilus biogenesis pilQ gene possessed by C. sakazakii strain E764. This gene encodes for a membrane protein which may serve as a pore for the exit of the conjugation pilus but also as a channel for entry of heme and antimicrobial agents and uptake of transforming DNA. These findings were supported by the development of a preliminary species-specific PCR assay designed to identify Cronobacter species based on single nucleotide differences associated with the γ1a fimbriae class usher gene as shown in Figure 3C.

FIGURE 3.

(A) Phylogenetic analysis among 15 fly Cronobacter strains (identified with a red dot) and 45 other Cronobacter and phylogenetically-related strains was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method using only 355 fimbriae alleles that are represented on the FDA Cronobacter FDACRONOa520845F microarray (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 1.22584234 is shown. The circular tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the p-distance method (Nei and Kumar, 2000) and are in the units of the number of base differences per site. The analysis involved 60 strains. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 336 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016). The microarray experimental protocol as described by Jackson et al. (2011) and as modified by Tall et al. (2015) was used for the interrogation of the strains for the analysis. The scale bar represents a 0.02 base substitution per site. (B) Chaperon-usher tree developed using alignments of the sequences. The scale bar represents a 0.2 base substitution per site. (C) PCR analysis of Cronobacter spp. using PCR primers which target the γ-1a usher-chaperon region. Lanes 1–10 from left to right represent bar markers, C. dublinensis subspecies dublinensis LMG 23823, C. dublinensis subspecies lausannensis LMG 23824, C. muytjensii ATCC 51329, C. universalis NCTC 9529, C. sakazakii BAA-894, C. malonaticus LMG 23826, C. turicensis LMG 23827, empty lane, and bar markers.

Presence of Phage and Prophage Genes

Figure 4 shows the relationship among filth fly strains analyzed with the microarray and the presence of phage- and prophage-related genes which are represented on the microarray. In contrast with the results of MA of the fimbriae-related genes shown in Figure 3A, the phage-associated genes were not species-specific in that interspecies clustering was observed among the Cronobacter species. The lack of species-specificity is not surprising given the promiscuity of phages. Nonetheless, though a phage-related species-specificity is not supported, the microarray can determine which phage genes are present in each strain. The microarray could not, however, determine if the presence of a phage in a particular strain is due to an active lysogenic event, or whether a phage is from a previous association that has lost its ability to be transmissible. More research is needed to further develop this hypothesis. Also, the fact that many Cronobacter phage can infect multiple species suggests that the surface structures used by the phage to infect cells are common among Cronobacter.

FIGURE 4.

Phylogenetic analysis among 15 fly Cronobacter strains (identified with a red dot) and 45 other Cronobacter and phylogenetically-related strains was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method using only 336 phage related alleles that are represented on the FDA Cronobacter FDACRONOa520845F microarray (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 2.31200965 is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the p-distance method (Nei and Kumar, 2000) and are in the units of the number of base differences per site. The analysis involved 60 strains. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 655 positions in the final dataset. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016, 2018). The scale bar represents a 0.02 base substitution per site.

Filth fly and C. sakazakii BAA-894 FASTA data sets were uploaded to the PHASTER web server and pipeline to identify phage genomic regions. One hundred and fourteen incomplete, questionable, and intact phage gene encoding regions were found and this information is described in Supplementary Table 4. Fifty of these 114 sequences were identified as being intact and contained genes encoding for noted phage components for tail, plate, capsid, head, portal, terminase, lysin, recombinase, and integrase proteins. Total intact phage operons ranged from 15.4 to 143.8 kbp in size and encoded for 19–186 total proteins. There were three different intact Cronobacter phage identified in 7 of the 19 filth fly stains and included phage ENT39118_NC_019934, ENT47670_NC_019927, and phiES15_NC_018454 in strains Anth48, Md1g, Md1sN, Md27gN, Md5g, Sh41g, and Sh41s. One other Cronobacter phage was found as an incomplete phage gene cluster, CsaM_GAP32_NC_019401 in strains Md1g and Md5g. The diversity of intact phage found among the filth fly strains include three instances of phiO18P (NC_009542), a phage that comes from Aeromonas media in fly strains: Lc10g, Md5s, and Md6g. Another four instances of an intact Edwardsiella phage GF-2 (NC_026611) was found in fly strains: Lc10s, Md33g, Md35s, and Md40g. Three different generalized transducing Enterobacterial phages [ES18 (NC_006949), mEp235 (NC_019708), and 186 (NC_001317)] were found intact in three different filth fly strains Anth48g, Md25g, and Md99g. Of note C. malonaticus Md99g possessed both mEp235 and phage 186. An intact Haemophilus influenzae phage, HP-2 (HP2_NC_003315) was found in filth fly C. turicensis Md1sN. Also an intact Mannheimia haemolytica phage, vB_MhM_3927AP2 (NC_028766) was found in fly strains: Lc10g, Lc10s, Md5s, Md6g. There were four different Salmonella phages identified in the 13 filth fly strain genomes. Of those identified there were 25 intact phages and these included ten intact SSU5 (NC_018843) phage in strains Anth48, Lc10g, Lc10s, Md1g, Md25g, Md27gN, Md5g, Md5s, Md6g, and Md70g. There were 12 intact 118970_sal3 (NC_031940) identified in Lc10g, Lc10s, Ls15g, Md1g, Md5g, Md5s, Md6g, Md70g, and Md99g. There was one SPN3UB (NC_019545) phage identified as intact in Md1sN, and SPN9CC (NC_017985) was identified as intact in strain Md25g. In total, phages from eight different bacterial species were identified in addition to the four Cronobacter phages. Furthermore, finding such diversity of phages infecting Cronobacter strains supports the phylogenetic diversity found by MA.

Presence of Hemolysin and Hemolysin-Related Genes

The gene encoding a hemolysin (hly) which may function in virulence was identified as a hemolysin III homolog (COG1272) by Cruz et al. (2011). Since then, several investigators have predicted that all Cronobacter species may possess a hemolysin III homolog (COG1272) gene (Kucerova et al., 2010; Grim et al., 2013; Moine et al., 2016). However, studies by Cruz et al. (2011), using a limited number of strains identified to the species level by using 16S RNA gene sequences and primers designed to target the gene, showed that some strains possessed the gene while others did not. Recently, Singh et al. (2017) described β-hemolytic activity in a limited number of C. sakazakii cultured from food, soil, and water; these strains were PCR-positive for the hemolysin III COG1272 allele. To better appreciate the gene prevalence and distribution, and phylogenetic relatedness of hemolysin III COG1272, we performed PCR analysis using the primers described by Cruz et al. (2011) on 390 Cronobacter strains of all species which were identified by species-specific PCR assays described by Stoop et al. (2009), Lehner et al. (2012), and Carter et al. (2013) and the results are shown in Table 4. PCR analysis demonstrated that hemolysin III COG1272 was present in 287/297 C. sakazakii; 3/7 C. muytjensii; 13/33 C. malonaticus; 3/12 C. turicensis; 3/36 C. dublinensis; and 1/1 C. universalis, respectively. C. condimenti was PCR-negative for hemolysin III COG1272. Parallel WGS analysis showed that all seven species do possess a hemolysin III COG1272 homolog but not necessarily present in all strains. Additionally, three other hemolysin genes were discovered by using this parallel next generation DNA sequence-based approach and these include genes encoding a cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) domain containing hemolysin, a putative hemolysin, and a 21-kDa hemolysin (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 3) and microarray analysis of the filth fly strains as well as certain Cronobacter species type strains showed that the filth fly C. malonaticus strains possessed the COG1272 hemolysin II homolog and cross hybridized with the COG1272 hemolysin II homolog from C. sakazakii BAA-894 and several of the other C. sakazakii filth fly strains such as Md5g, Md5s, Md6g, and Md70g and C. turicensis filth fly strain Sh41g. The COG1272 hemolysin homolog from BAA-894 cross hybridized with all of the filth fly C. malonaticus strains and all the C. sakazakii filth fly strains except for Md1g. Lastly, the probesets representing this gene from C. condimenti, C. dublinensis, C. muytjensii all hybridized with their respective donor strain. These results support the PCR findings that some strains of the Cronobacter species share this homolog. The 21-kDa hemolysin precursor from C. turicensis LMG 23827T cross hybridized with C. dublinensis 5960-70, C. malonaticus LMG 23826T, six of the 12 C. sakazakii filth fly strains, and all of the C. turicensis filth fly strains as well as the two C. universalis analyzed. There were three probesets representing a hemolysin and related proteins containing a CBS domain gene from C. condimenti, C. dublinensis, and C. turicensis. The results showed that the C. condimenti probeset only hybridized with C. condimenti strain LMG 26250. The C. dublinensis probeset hybridized only with the C. dublinensis strains. However, the C. turicensis probeset hybridized with C. turicensis type stain LMG 23827T and C. turicensis filth fly strain Sh41s, and cross hybridized with C. sakazakii filth fly strain Md27gN and C. universalis species type strain NCTC 9529T. The putative hemolysin allele was found intermittently among the strains that were analyzed. Umeda et al. (2017) recently reported that 57 Cronobacter strains exhibited β-hemolytic activity against guinea pig, horse and rabbit erythrocytes. However, using sheep erythrocytes, the majority of strains (53/57; 92.9%) showed α-hemolysis. Taken together, these results suggest that the primers designed by Cruz et al. (2011) may not detect hemolysin III COG1272 orthologs in all Cronobacter species uniformly and more in-depth genetic studies are needed to assign functionality of these various hemolysin genes to a hemolytic phenotype.

TABLE 4.

Results of PCR analysis showing the prevalence and distribution of the hemolysin III COG1272 gene among 390 Cronobacter strains*.

| Species | No. of strains PCR negative | No. of strains PCR positive | No. of strains tested | % positive |

| C. sakazakii | 10 | 287 | 297 | 96.6 |

| C. muytjensii | 4 | 3 | 7 | 42.9 |

| C. malonaticus | 20 | 13 | 33 | 39.4 |

| C. turicensis | 9 | 3 | 12 | 25 |

| C. dublinensis | 33 | 3 | 36 | 8.3 |

| C. condimenti | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| C. universalis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Total | 79 | 311 | 390 | 79.7 |

*All strains were identified to their species epithet by using the species-specific PCR assays described by Stoop et al. (2009), Lehner et al. (2012), and Carter et al. (2013). Primer sequences and PCR reaction conditions were carried out according to Cruz et al. (2011). The hemolysin III COG 1272 gene ID in BAA-894 is ESA_RS01960, alias ESA_00432, and its location spans between 409401 and 410054 bp. The amplicon size of the PCR product spans from 409290 to 410170 and is 880 bp in size.

Genome-Wide Analysis of Virulence-Associated Genes

To date, the Cronobacter microarray contains 40 genes that are annotated as putative or virulence-associated factors and represent a mixture of orthologous and species-specific genes from all seven species. Distribution of the homologs of these virulence-associated factors evaluated by MA provided a highly comparable profile of these predicted genes. The presence-absence calls (by MA) for these genes are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Notable genes (and NCBI protein ID) include the virulence factor MviM (ABU77528/ESA_02279), virulence protein MsgA (ABU76496/ESA_01234), virulence factor VirK (ABU77707/ESA_02461), putative virulence effector protein (ABU77161/ESA_01907), and the virulence-associated protein vagC (AHB72624). For the most part, the distribution of putative homologs followed evolutionary species and ST lines. However, there are a few genes which were shared among the these species: included a gene encoding a virulence protein MsgA from C. dublinensis subspecies lausannensis (NCBI ID ABU76496/ESA_01234) that was shared with filth fly C. sakazakii Md5g and Md6g, and the C. turicensis filth fly strain Md1sN. Virulence factor VirK (ABU77707/ESA_02461) from species type strain C. universalis NCTC 9529T is shared with C. sakazakii fly strains A48g, Md27gN, and Md35s. Virulence-associated protein vagC (AHB72624) from C. turicensis type strain LMG 23827T is also present in the three C. turicensis fly strains, Md1sN, Sh41g, and Sh41s; as well as in C. malonaticus fly strain Md25g, C. sakazakii fly strains Md1g, Md33g, Md33s, Md35s, Md40g, and Md5g, which suggests that vagC is in other Cronobacter species besides C. turicensis. Virulence factor MviM from C. turicensis type strain LMG 23827T was also identified in C. turicensis fly strains Md1sN and Sh41s and was also found in C. sakazakii fly strains Md35s, Md5g, Md6g and Md70g.

BLAST analysis of the fly strain genomes using nucleotide sequences from BAA-894 resulted in identifying the distribution of the homologs of 32 virulence-associated genes as presented in the Supplementary Table 5.

Core Gene Analysis and Comparative Genomics

Spine analysis was carried out on the filth fly genomes and from six of the seven Cronobacter species with C. sakazakii BAA-894 as the reference at 85, 90, and 95% levels of homology. This resulted in identifying 3,329, 2,905, and 767 core genes, respectively (Data not shown). Presence of C. condimenti genes impacted the homology threshold significantly and the genome was treated as an outlier in the final analyses. Considering the genomic diversity of Cronobacter species, a 90% cutoff value was set for refining the whole genome core gene (wg-core) loci to yield ∼2,790 genes consistently present in C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus, and C. turicensis branches of the distichously formed genomic tree as described by Grim et al. (2013). A data matrix was generated with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) present in the 19 genomes from the seven species in these backbone loci by BLAST analysis (data not shown) which re-created the genome diversity patterns observed earlier (Grim et al., 2013; Stephan et al., 2014; Tall et al., 2015; Chase et al., 2016; Gopinath et al., 2018; Jang et al., 2020) by WGS and the pan-genome microarray. The top 2,000 genes with a higher mutation rate from this data matrix were chosen as the Cronobacter final backbone reference wg-core gene set for subsequent analyses.

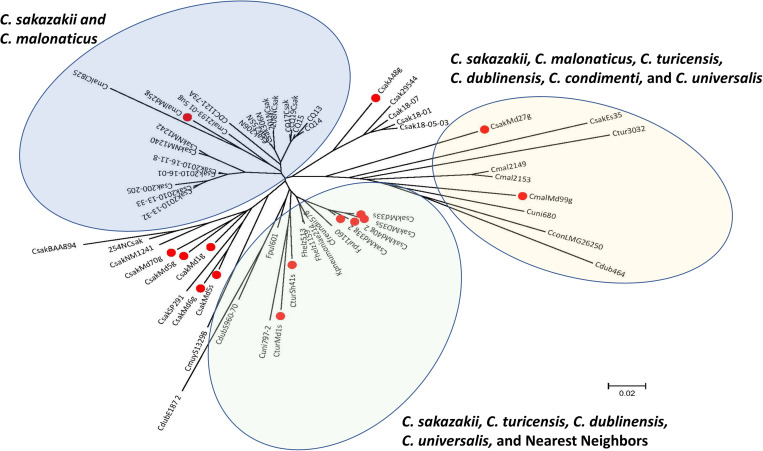

Phylogenetic analysis of draft genomes from the fly strains were carried out by analyzing their genomes for SNPs specifically in these 2,000 reference core gene loci. The newly designed Cronobacter wg-core analysis clustered filth fly, reference and some clinical strains with a high resolution in a phylogenetic tree with manually curated MLST information added (Figure 5). Individual strain differences within some stains possessing similar STs were highlighted by this method. This analysis (Figure 5) demonstrates that ST4 C. sakazakii filth fly strains Lc10g, Lc10s, Md6g, Md5s, Md1g, Md5g, and Md70g clustered indistinguishably with a ST4 clinical strain C. sakazakii 8155 and a highly persistent Irish PIF manufacturing environmental strain SP291. Additionally, ST8 C. sakazakii O:1 fly strains Md35s, Md40g, Md33s, Md33g, and ST221 strain Anth48g clustered indistinguishably with ST8 C. sakazakii O:1 clinical strain ATCC 29544T. Similarly, ST7 C. malonaticus O:2 fly strain Md25g clustered indistinguishably with ST7 C. malonaticus O:2 clinical strain LMG 23826T and strain Md99g clustered nearby to ST307 (CC112) C. malonaticus O:1 clinical strain 2193-01 (NCBI alias CmalFDA827). Lastly, ST569 C. turicensis strains Sh41g and Sh41s clustered indistinguishably with ST19 C. turicensis O:1 type strain LMG 23827T and fly strain Md1sN clustered closely within this C. turicensis strain cluster.

FIGURE 5.