Abstract

BACKGROUND

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammation of periodontal tissues. The effect of periodontitis on the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) remains unclear.

AIM

To assessed the risk of IBD among patients with periodontitis, and the risk factors for IBD related to periodontitis.

METHODS

A nationwide population-based cohort study was performed using claims data from the Korean National Healthcare Insurance Service. In total, 9950548 individuals aged ≥ 20 years who underwent national health screening in 2009 were included. Newly diagnosed IBD [Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC)] using the International Classification of Disease 10th revision and rare intractable disease codes, was compared between the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups until 2017.

RESULTS

A total of 1092825 individuals (11.0%) had periodontitis. Periodontitis was significantly associated with older age, male gender, higher body mass index, quitting smoking, not drinking alcohol, and regular exercise. The mean age was 51.4 ± 12.9 years in the periodontitis group and 46.6 ± 14.2 years in the non-periodontitis group (P < 0.01), respectively. The mean body mass index was 23.9 ± 3.1 and 23.7 ± 3.2 in the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups, respectively (P < 0.01). Men were 604307 (55.3%) and 4844383 (54.7%) in the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups, respectively. The mean follow-up duration was 7.26 years. Individuals with periodontitis had a significantly higher risk of UC than those without periodontitis [adjusted hazard ratio: 1.091; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.008-1.182], but not CD (adjusted hazard ratio: 0.879; 95% confidence interval: 0.731-1.057). The risks for UC were significant in the subgroups of age ≥ 65 years, male gender, alcohol drinker, current smoker, and reduced physical activity. Current smokers aged ≥ 65 years with periodontitis were at a 1.9-fold increased risk of UC than non-smokers aged ≥ 65 years without periodontitis.

CONCLUSION

Periodontitis was significantly associated with the risk of developing UC, but not CD, particularly in current smokers aged ≥ 65 years.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Periodontitis, Smoking, Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease

Core Tip: We evaluate the impact of periodontitis on the development of ulcerative colitis (UC) using the nationwide population-based cohort data. In total, 9950548 individuals undergoing national health screenings in 2009 were included in this study and were followed for an average of 7.26 years. Patients with periodontitis had a higher risk of UC than those without periodontitis. Current smokers over 65 years with periodontitis were at a 1.9-fold increased risk of UC than non-smokers without periodontitis. Periodontitis was significantly associated with the risk of UC and cigarette smoking could superimpose the impact of periodontitis on UC, especially in elderly people.

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is a chronic infectious and inflammatory disease of periodontal tissues caused by interactions between the microbiota in the root canals and the host immune system[1]. Periodontitis can be caused by a variety of etiologies, such as alveolar bone destruction, dental plaque bacteria, remnant food material, and an abnormal immune response[2]. The prevalence of periodontitis ranges from 20% to 50% globally and increases with age[3,4]. Risk factors for periodontitis, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, have been reported in previous studies[5,6]. Furthermore, periodontitis is closely linked to the pathogenesis of systemic disease[7,8].

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic relapsing inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract with many causes. Complex interactions among gut dysbiosis, changes in the host immune system, and genetic factors affect the development of IBD. In Asia, the prevalence of IBD is rapidly increasing, and its genetic predisposition and environmental impact is different from that of western countries[9]. Environmental factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption can be associated with the development of IBD. The effects of smoking on the pathogenesis of CD and UC are different. Smoking may have a minor role in the development of CD in Asia, unlike western populations[10]. In contrast, former smokers have a significantly higher risk of developing UC than non-smokers[11]. Alcohol consumption is related to exacerbation of symptoms in patients with IBD[12].

The destruction of periodontal tissues might induce activation of a variety of cytokines related to the pathophysiology of IBD[13]. In addition, changes in the gut microbiota and immunosuppressive agents used to treat IBD can deteriorate oral health via changes in the oral microbiota, resulting in an increased risk for periodontitis[14,15]. Periodontitis and IBD are characterized by chronic inflammation initiated in the oro-intestinal tract, and share a number of similar pathophysiological features. However, the pathogenic relationship between periodontitis and IBD remains unclear. Epidemiological studies regarding the effects of periodontitis based on age and environmental factors on the occurrence of IBD are lacking. The aims of the study were to assess the incidence and risk of IBD among patients with periodontitis and identify the risk factors for the occurrence of IBD related to periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Database

The National Health Insurance (NHI) service is a single, mandatory medical insurer providing a health insurance to approximately 51 million citizens in South Korea. The NHI database contains information on comorbidities, drug prescriptions, treatment, and demographic characteristics of Koreans due to the unique nature of the NHI service. The National Health Screening Program (NHSP) is conducted every 2 years for all qualified adults > 20 years of age, and the information collected by the NHSP accumulates as a separate cohort. Clinical data at baseline and trends in changes in the data can be evaluated in the cohort. The Rare and Intractable Diseases (RID) system supports additional medical costs for patients with RIDs, such as IBD. We identified the RIDs with a special diagnostic code (V code). CD is a rare disease, and UC is regarded as an intractable disease in South Korea.

Study population

This was a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study using the NHI claims data from a population who underwent the NHSP in 2009 (index year). Patients were classified into the periodontitis group when the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 code for periodontitis (K05.3) was identified at the index examination. The periodontitis group was divided into three stages according to the severity of periodontitis based on therapeutic procedures, including scaling, sub-gingival curettage, and surgery. Individuals without periodontitis were considered the non-periodontitis group. In both groups, patients who were diagnosed with IBD from 2004 to 2009 were excluded to rule out IBD cases not related to periodontitis (washout period). Newly diagnosed IBD patients in the first year after the index year were also excluded (lag period). Patients who were newly diagnosed with periodontitis during the follow-up period in the non-periodontitis group were censored in this study.

Definition and data acquisition

Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, exercise, income, comorbidities, and laboratory findings were collected in the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups. Smoking was classified as current smoker, ex-smoker, and nonsmoker based on a questionnaire[11]. Current smokers were defined as those who had smoked more than five packs of cigarettes throughout their lives and continued cigarette smoking. Ex-smokers were defined as those who had smoked more than five packs of cigarettes but quit smoking at least 1 mo ago. Non-smokers were defined as those who had no experience with cigarette smoking or had smoked less than five packs throughout their lifetime. Alcohol drinking was categorized into non-drinker, mild, and excessive drinker. The excessive drinker was defined as consuming more than 30 g per day of alcohol[16]. Exercise was considered ‘yes’ according to the questionnaire when the participant performed moderate-intensity exercise for 30 min or vigorous-intensity exercise for 20 min at least once per week[17]. Obesity was defined as BMI > 25 kg/m2, and central obesity was defined as a waist circumference > 90 cm in males and > 85 cm in females. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg, or ICD-10 code (I10-13, I15) and a prescription for anti-hypertensive medication[18,19]. Diabetes was identified using an ICD-10 code (E11-14) and anti-diabetic medication or fasting glucose levels ≥ 126 g/dL[16]. Dyslipidemia was defined using ICD-10 code (E78) and taking one of the lipid-lowering agents, or a total cholesterol level ≥ 240 mg/dL. Laboratory data, including serum glucose, total cholesterol, gamma glutamyltransferase and triglyceride levels, were also collected.

End points

The study population was followed up from the index date to December 31, 2017. Newly diagnosed IBD was the study endpoint. IBDs, including CD and UC were identified with the ICD-10 code (K50 for CD and K51 for UC) and the V code for RIDs (V130 for CD and V131 for UC), as defined previously[11,16,18-25]. The risk for IBD was compared between the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups, according to age, sex, smoking, alcohol drinking, exercise, obesity, and central obesity. In addition, we investigated the specific risk groups for developing UC in a subgroup analysis. This study was approved by International Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (H-1703-107-840) and the Korean NHI.

Statistical analysis

Base characteristics of study population were analyzed by χ2 test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. The incidence rate was represented by incident cases of IBD per 100000 person-years. Cumulative incidence probability of CD and UC was shown using Kaplan-Meyer methods and the log-rank test. Hazard ratio (HR) of CD and UC in the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups was calculated using Cox-proportional hazard models adjusted by age, sex, smoking, alcohol drinking, exercise, BMI, and income. A P value less than 0.05 is considered significant. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population

A total of 9950548 participants were included in this study. Among them, 1092825 subjects (11.0%) had periodontitis. The demographic characteristics and baseline laboratory profile are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 51.4 ± 12.9 years in the periodontitis group and 46.6 ± 14.2 years in the non-periodontitis group, respectively (P < 0.0001). The periodontitis group was significantly older, had a higher proportion of males, and a higher BMI and waist circumference than those in the non-periodontitis group (P < 0.0001 for each variable). Patients with periodontitis had significantly higher proportions of individuals quitting smoking, not drinking alcohol, but performing regular exercise, compared with the non-periodontitis group (P < 0.0001 for each variable). Comorbid hypertension and diabetes were significantly associated with periodontitis (P < 0.0001 for each variable). Serum glucose, total cholesterol, gamma glutamyltransferase, and triglyceride levels were significantly higher in the periodontitis group than the non-periodontitis group (P < 0.0001 for each variable).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Periodontitis | Non-periodontitis | P value | |

| Patients, n | 1092825 | 8857723 | |

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) | 51.4 ± 12.9 | 46.6 ± 14.2 | < 0.01 |

| Age, 3 groups (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| 20-39 | 188805 (17.2) | 2929998 (33.1) | |

| 40-64 | 719197 (65.8) | 4810132 (54.3) | |

| ≥ 65 | 184823 (16.9) | 1117593 (12.6) | |

| Male (%) | 604307 (55.3) | 4844383 (54.7) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 23.9 ± 3.1 | 23.7 ± 3.2 | < 0.01 |

| Waist circumference, cm (mean ± SD) | 81.2 ± 8.8 | 80.1 ± 9.1 | < 0.01 |

| Cigarette smoking (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 644790 (59.0) | 5276142 (59.6) | |

| Ex-smoker | 188825 (17.3) | 1238268 (14.0) | |

| Current smoker | 259210 (23.7) | 2343313 (26.4) | |

| Drinking (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| Non | 597901 (54.7) | 4528675 (51.1) | |

| Mild | 423429 (38.8) | 3718,835 (42.0) | |

| Heavy | 71495 (6.5) | 610213 (6.9) | |

| Exercise; yes (%) | 572684 (52.4) | 4544197 (51.3) | < 0.01 |

| Income; low (less than 20% of total population) (%) | 274356 (25.1) | 2347661 (26.5) | < 0.01 |

| Underlying illness | < 0.01 | ||

| Hypertension (%) | 338855 (31.0) | 2220906 (17.8) | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 123.1 ± 15.0 | 122.3 ± 14.9 | |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 76.6 ± 10.0 | 76.3 ± 10.0 | |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 244342 (22.4) | 1574251 (17.8) | |

| Diabetes (%) | 131663 (12.1) | 734481 (8.3) | |

| Initial laboratory findings | |||

| Glucose, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 99.6 ± 25.3 | 96.8 ± 22.6 | < 0.01 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 196.8 ± 37.0 | 191.7 ± 35.4 | < 0.01 |

| GGT, IU/L (median and 95%CI) | 28.5 (28.4–28.6) | 27.4 (27.4–27.42) | < 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL (median and 95%CI) | 117.9 (117.7–117.9) | 113.2 (113.1–113.2) | < 0.01 |

SD: Standard deviation; BMI: Body mass index; BP: Blood pressure; GGT: Gamma glutamyltransferase; CI: Confidence interval.

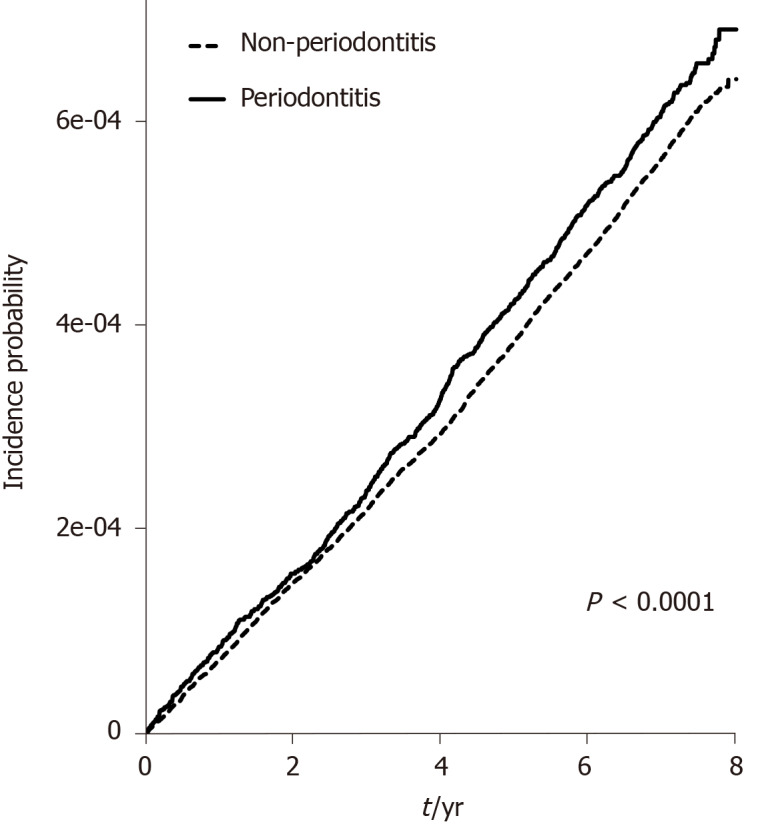

Risk of developing IBD

The mean follow-up duration was 7.26 ± 0.76 years. The incidence rate values of UC represented by newly diagnosed cases per 100000 person-years were 7.1 and 7.7 in the non-periodontitis and periodontitis groups, respectively (Table 2). The cumulative incidence of UC was significantly higher in the periodontitis group than in the non-periodontitis group (P < 0.0001) (Figure 1). The HR of UC adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking, alcohol drinking, exercise, and income was 1.091 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.008–1.182] in the periodontitis group. However, periodontitis did not increase the risk of CD compared with not having periodontitis (adjusted HR: 0.879; 95%CI: 0.731–1.057). The HRs of UC and CD in the periodontitis group did not differ significantly from those in the non-periodontitis group (data not shown).

Table 2.

The incidence and risk for inflammatory bowel disease in patients with periodontitis

|

UC |

CD |

||||||

| n | UC | IR | aHR (95%CI) | CD | IR | aHR (95%CI) | |

| Periodontitis | |||||||

| No | 8857723 | 5224 | 7.1433 | 1 (ref.) | 1300 | 1.7773 | 1 (ref.) |

| Yes | 1092825 | 692 | 7.6730 | 1.091 (1.008-1.182) | 126 | 1.3968 | 0.879 (0.731-1.057) |

The incidence rate is represented by incident cases of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease per 100000 person-years. The hazard ratio was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking, alcohol drinking, exercise, and income. UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; IR: Incidence rate; aHR: Adjusted hazard ratio; CI: Confidence intervals.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of ulcerative colitis in patients with and without periodontitis.

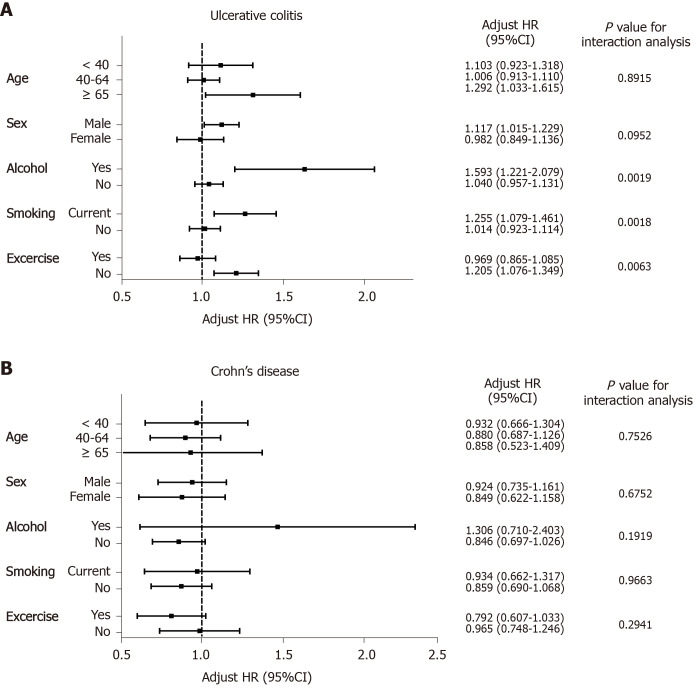

Subgroup analysis

A subgroup analysis of the comparative risk for developing UC and CD was performed based on age, sex, alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and exercise (Figure 2A and B). We compared the risk of developing UC between the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups by dividing the two groups into three subgroups according to age: < 40 years, 40-64 years, and > 65 years. The significant comparative risk of developing UC was found only in the subgroup > 65 years (adjusted HR: 1.292; 95%CI: 1.033-1.615). The risk of UC in male patients with periodontitis was significantly higher than those without periodontitis (adjusted HR: 1.117; 95%CI: 1.015–1.229), but not in females. Significantly increased risks of developing UC were detected in the periodontitis group among the subgroups with excessive alcohol drinking (adjusted HR: 1.593; 95%CI: 1.221-2.079), current smoking (adjusted HR: 1.255; 95%CI: 1.079-1.461), and no regular exercise (adjusted HR: 1.205; 95%CI: 1.076-1.349). Periodontitis did not significantly increase the risk of developing UC among the subpopulations with obesity and central obesity.

Figure 2.

Subgroup analysis of the comparative risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in patients with periodontitis compared with those without periodontitis. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. A: Ulcerative colitis; B: Crohn’s disease. HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

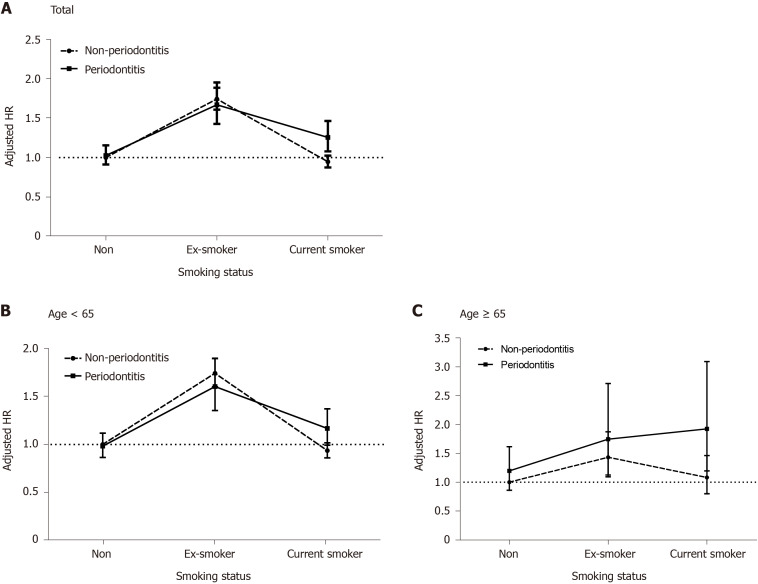

Risks of developing UC according to cigarette smoking behavior

We investigated the risks of developing UC in the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups, respectively, according to smoking behavior (Figure 3). Ex-smokers in both groups had the highest risks of developing UC compared to nonsmokers without periodontitis, but the difference in the adjusted HRs between the periodontitis (adjusted HR: 1.667; 95%CI: 1.425-1.950) and non-periodontitis groups (adjusted HR: 1.740; 95%CI: 1.606-1.884) among ex-smokers was not significant. However, current smokers in the periodontitis group (adjusted HR: 1.255; 95%CI: 1.078-1.462) had a significantly higher risk of developing UC, but not those in the non-periodontitis group (adjusted HR: 0.946; 95%CI: 0.874–1.025) compared to nonsmokers without periodontitis. A significant difference in adjusted HRs was observed between the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups among current smokers (Figure 3A). The significant risk of developing UC in current smokers with periodontitis (adjusted HR: 1.924; 95%CI: 1.197–3.092) was more pronounced in the elderly subgroup > 65 years than in nonsmokers without periodontitis (Figure 3B and C).

Figure 3.

The risk for developing ulcerative colitis with age and cigarette smoking behavior in the periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. A: All ages; B: Age < 65; C: Age ≥ 65. HR: Hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

This population-based cohort study of approximately 10 million individuals reported that periodontitis significantly increased the risk of developing UC, but not CD, compared to those without periodontitis. The effect of periodontitis on the risk of developing UC was prominent, particularly among elderly male current smokers who drank alcohol and participated in reduced physical activity. In particular, current smoking and the presence of periodontitis had a synergistic effect on the occurrence of UC in the elderly. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest epidemiological study demonstrating the impact of periodontitis on the development of IBD based on demographic and environmental factors.

The risk for periodontitis among patients with IBD has been reported in recent studies[15,26-28]. In a matched-cohort study demonstrating the prevalence and relative risk of periodontitis, patients with CD were at a 1.36-fold increased risk for periodontitis than controls[29]. The relative risk of periodontitis is also significantly higher in patients with UC[30], especially in smokers[31], which suggests that periodontitis is an oral manifestation of IBD. Periodontitis may occur as a complication of IBD itself or as an adverse event related to IBD therapeutic agents. Changes in the host immune system in patients with a systemic disease may affect oral mucosal immunity. Subgingival microflora changes have been detected in patients with IBD and periodontitis[32], and dysregulation of the host immune system, such as in Th17 cells and the interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 axis have been proposed to be involved in the pathophysiology of periodontitis related to IBD[33].

In contrast, there is little evidence regarding the risk of developing IBD in patients with periodontitis. A Taiwanese cohort study reported a 1.56-fold significantly higher risk of UC, but not CD, in 27000 patients with periodontal diseases, including acute periodontitis, chronic periodontitis, and gingivitis[34], which is comparable with our results in a nationwide study of 1 million subjects with chronic periodontitis. Our study has the strength of demonstrating the impacts of chronic periodontitis, which may reflect the dynamics of chronic inflammatory conditions and lifestyle factors, such as cigarette smoking, on the pathogenesis of IBD. Taken together, the risk of developing UC increased significantly in patients with periodontitis, although the relatively low HR for UC in the periodontitis group needs to be evaluated by epidemiologic studies in other countries.

The effect of periodontitis on the pathogenesis of UC may be associated with dysbiosis in the oral and intestinal microenvironments[35]. The role of the gut microbiota is critical in the pathogenesis of IBD in terms of nutrition, host immune response, and defense[36]. UC is associated with reduced microbial diversity and depletion of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes in the gastrointestinal tract. Gut dysbiosis in IBD, particularly UC, is associated with changes in the salivary microbiome[37]. Therefore, oral hygiene and biofilms related to periodontitis might affect the initiation and perpetuation of inflammation via dysbiosis in the colon. In contrast, the dynamic interactions between the oral microenvironment and the development of intestinal inflammation in patients with CD are weak. In a recent population-based cohort study in Sweden, dental plaques were negatively associated with a 68% reduced risk of CD[38]. The dynamic impacts of oral hygiene on dysbiosis and chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract should be clarified in further research.

We determined that the risk groups for UC related to periodontitis were elderly, male, alcohol drinking, current smoking, and reduced physical activity. These demographic and lifestyle factors that can alter oral hygiene have crucial effects on the development of UC among patients with periodontitis. Cigarette smoking may have a protective effect on the development of UC, while quitting smoking increases the risk of developing UC[39-42]. However, smoking and smoking cessation was not associated with disease course of UC[42]. Recent studies have demonstrated a dose-response relationship between quitting smoking and the risk of developing UC[11,43]. In line with previous results, ex-smokers had the highest risk of developing UC, regardless of the presence of periodontitis and age in this study. In contrast, current smoking effect on the prevention of UC is still controversial depending on subgroups such as ethnicity and gender. Interestingly, the comparative risk of developing UC in the elderly tended to be more pronounced in current smokers than in ex-smokers, suggesting that the synergistic effects of periodontitis and cigarette smoking increase the risk of elderly onset UC. Cigarette smoking causes changes in both oral and intestinal microbial composition[44,45], and may play a key role as an environmental cause of UC via oral and gut dysbiosis. Cigarette smoking affects microbial diversity and composition resulting in decreases in Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes and increases in Firmicutes[46]. A Treponema denticola infection is frequently detected in current smokers with periodontal disease[47]. Further research is needed to determine the combined effects of cigarette smoking and periodontitis on the pathogenesis of elderly onset UC, in terms of oral dysbiosis.

The incidence of UC shows a bimodal distribution in the age at onset[48-51], and the second peak of incidence in the elderly is closely related to the environmental etiologies of UC. Surprisingly, the age-specific incidence of UC is in a steady state between the ages of the 20 s to 60 s with the highest rates for men in their 60 s in a recent 30-year follow-up epidemiological study from South Korea[50]. The consistent evidence of ex-smokers related to the risk of UC development and the harmful synergistic effects of current cigarette smoking and periodontitis in the elderly provide an important clue to explain the role of environmental etiologies in the complex pathophysiology of elderly onset UC.

The present study had several limitations due to its retrospective design. First, the severity and disease extent of IBD could not be investigated. Second, the risk of developing IBD among patients with periodontitis was not adjusted by medication. Antibiotics are possible confounders in the relationship between periodontitis and IBD but are generally used within a short period in actual practice in this general population. It is assumed that the chaotic effects of antibiotics might be minimized considering the median follow-up period of more than 7 years. Use of corticosteroids and immunomodulatory agents could not be also identified due to the limitations of claims data. Third, the operational definition for the severity of periodontitis was not validated, although there was no significant difference in the comparative risk of developing UC based on the severity of periodontitis. Further prospective research is required to assess how the severity of periodontitis and oral dysbiosis affect the risk of developing UC.

CONCLUSION

Periodontitis was significantly associated with the risk of developing UC, but not CD. Current smoking superimposed the impacts of periodontitis on the occurrence of elderly onset UC. These findings suggest that adding cigarette smoking in the background of periodontitis are potential risk factors for elderly onset UC.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Environmental factors in addition to genetic and immunological factors are known to influence on the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). The effects of etiologies such as smoking, alcohol consumption, age and comorbidities on the occurrence of chronic intestinal inflammation may vary based on race and gender.

Research motivation

Gut dysbiosis is associated with IBD as a cause or result and is related to oral microflora. Oral disease can occur as an extra-intestinal manifestation of IBD. However, the risk of developing IBD in patients with periodontitis remains unclear.

Research objectives

We aimed to evaluate the risk of developing IBD in patients with periodontitis and to determine the combined effect of risk factors on the development of IBD associated with periodontitis.

Research methods

Using database of the National Health Insurance and National Health Screening Program in South Korea in 2009, we compared people with and without periodontitis and evaluated newly diagnosed IBD in both group during follow-up period until 2017. All 9950548 people over the age of 20 who received a national health check in 2009 were included. Periodontitis was defined using the International Classification of Disease 10th revision (ICD-10). CD and UC were defined using ICD-10 and rare intractable disease codes specific to South Korea.

Research results

Out of 9950548 individuals, a total of 1092825 subjects (11.0%) had periodontitis. The periodontitis group was older and had a higher male proportion. During the median follow-up period of 7.26 years, people with periodontitis had a significantly higher risk of developing UC than those without periodontitis. In a subgroup analysis, current smokers aged 65 and older with periodontitis had a 1.9-fold increase in UC risk than non-smokers aged 65 and older without periodontitis.

Research conclusions

Periodontitis is highly associated with the risk of developing UC, especially in current smokers over 65. It suggests that periodontitis and current smoking are a potential combined risk factor for the development of elderly-onset UC.

Research perspectives

Based on the results of this study, we need future prospective studies to focus on the synergistic impacts of the environmental risk factors on elderly onset UC in terms of complex interaction of oral and intestinal microflora. Ultimately, it can lead to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of IBD.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Seoul National University Hospital, No. H-1703-107-840.

Informed consent statement: The subjects’ information in the database was de-identified before the investigator accessed the data, thus informed consent was waived.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: May 18, 2020

First decision: July 29, 2020

Article in press: September 16, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ramakrishna B, Sales-Campos H S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Eun Ae Kang, Department of Internal Medicine and Institute of Gastroenterology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul 03722, South Korea.

Jaeyoung Chun, Department of Internal Medicine, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul 06229, South Korea. chunjmd@yuhs.ac.

Jee Hyun Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Bundang CHA Medical Center, CHA University School of Medicine, Seoul 13496, South Korea.

Kyungdo Han, Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science, Soongsil University, Seoul 06978, South Korea.

Hosim Soh, Department of Internal Medicine and Liver Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, South Korea.

Seona Park, Department of Internal Medicine and Liver Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, South Korea.

Seung Wook Hong, Department of Internal Medicine and Liver Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, South Korea.

Jung Min Moon, Department of Internal Medicine and Liver Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, South Korea.

Jooyoung Lee, Department of Internal Medicine and Liver Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, South Korea.

Hyun Jung Lee, Department of Internal Medicine and Liver Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, South Korea.

Jun-Beom Park, Department of Periodontics, the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul 06591, South Korea.

Jong Pil Im, Department of Internal Medicine and Liver Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, South Korea.

Joo Sung Kim, Department of Internal Medicine and Liver Research Institute, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, South Korea.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Slots J. Periodontitis: facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontol 2000. 2017;75:7–23. doi: 10.1111/prd.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyle J, Chapple I. Molecular aspects of the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2015;69:7–17. doi: 10.1111/prd.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Slade GD, Thornton-Evans GO, Borgnakke WS, Taylor GW, Page RC, Beck JD, Genco RJ. Update on Prevalence of Periodontitis in Adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2015;86:611–622. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eke PI, Wei L, Borgnakke WS, Thornton-Evans G, Zhang X, Lu H, McGuire LC, Genco RJ. Periodontitis prevalence in adults ≥ 65 years of age, in the USA. Periodontol 2000. 2016;72:76–95. doi: 10.1111/prd.12145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albandar JM. Epidemiology and risk factors of periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:517–532, v-vi. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genco RJ, Borgnakke WS. Risk factors for periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:59–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michaud DS, Fu Z, Shi J, Chung M. Periodontal Disease, Tooth Loss, and Cancer Risk. Epidemiol Rev. 2017;39:49–58. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxx006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong C, Wang YH, Chang YC. Increased Risk of Carotid Atherosclerosis in Male Patients with Chronic Periodontitis: A Nationwide Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng WK, Wong SH, Ng SC. Changing epidemiological trends of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Intest Res. 2016;14:111–119. doi: 10.5217/ir.2016.14.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SC, Jeen YT. Role of Smoking as a Risk Factor in East Asian Patients with Crohn's Disease. Gut Liver. 2017;11:7–8. doi: 10.5009/gnl16534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park S, Chun J, Han KD, Soh H, Kang EA, Lee HJ, Im JP, Kim JS. Dose-response relationship between cigarette smoking and risk of ulcerative colitis: a nationwide population-based study. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:881–890. doi: 10.1007/s00535-019-01589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khasawneh M, Spence AD, Addley J, Allen PB. The role of smoking and alcohol behaviour in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31:553–559. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figueredo CM, Brito F, Barros FC, Menegat JS, Pedreira RR, Fischer RG, Gustafsson A. Expression of cytokines in the gingival crevicular fluid and serum from patients with inflammatory bowel disease and untreated chronic periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:141–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2010.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasovic M, Gajovic N, Brajkovic D, Jovanovic M, Zdravkovaic N, Kanjevac T. The relationship between the immune system and oral manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2016;41:302–310. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2016.63131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papageorgiou SN, Hagner M, Nogueira AV, Franke A, Jäger A, Deschner J. Inflammatory bowel disease and oral health: systematic review and a meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:382–393. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang EA, Han K, Chun J, Soh H, Park S, Im JP, Kim JS. Increased Risk of Diabetes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Nationwide Population-based Study in Korea. J Clin Med. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/jcm8030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Task Force on Community Preventive Services. A recommendation to improve employee weight status through worksite health promotion programs targeting nutrition, physical activity, or both. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:358–359. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S, Chun J, Han KD, Soh H, Choi K, Kim JH, Lee J, Lee C, Im JP, Kim JS. Increased end-stage renal disease risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide population-based study. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4798–4808. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i42.4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soh H, Chun J, Han K, Park S, Choi G, Kim J, Lee J, Im JP, Kim JS. Increased Risk of Herpes Zoster in Young and Metabolically Healthy Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Gut Liver. 2019;13:333–341. doi: 10.5009/gnl18304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J, Im JP, Han K, Kim J, Lee HJ, Chun J, Kim JS. Changes in Direct Healthcare Costs before and after the Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Gut Liver. 2020;14:89–99. doi: 10.5009/gnl19023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Chun J, Lee C, Han K, Choi S, Lee J, Soh H, Choi K, Park S, Kang EA, Lee HJ, Im JP, Kim JS. Increased risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:249–255. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi K, Chun J, Han K, Park S, Soh H, Kim J, Lee J, Lee HJ, Im JP, Kim JS. Risk of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide, Population-Based Study. J Clin Med. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/jcm8050654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J, Im JP, Han K, Park S, Soh H, Choi K, Kim J, Chun J, Kim JS. Risk of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A nationwide, population-based study. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:6354–6364. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i42.6354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soh H, Im JP, Han K, Park S, Hong SW, Moon JM, Kang EA, Chun J, Lee HJ, Kim JS. Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are associated with different lipid profile disorders: a nationwide population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:446–456. doi: 10.1111/apt.15562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park S, Kim J, Chun J, Han K, Soh H, Kang EA, Lee HJ, Im JP, Kim JS. Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Are at an Increased Risk of Parkinson's Disease: A South Korean Nationwide Population-Based Study. J Clin Med. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/jcm8081191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poyato-Borrego M, Segura-Sampedro JJ, Martín-González J, Torres-Domínguez Y, Velasco-Ortega E, Segura-Egea JJ. High Prevalence of Apical Periodontitis in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Age- and Gender- matched Case-control Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:273–279. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauritano D, Boccalari E, Di Stasio D, Della Vella F, Carinci F, Lucchese A, Petruzzi M. Prevalence of Oral Lesions and Correlation with Intestinal Symptoms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019;9 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics9030077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piras V, Usai P, Mezzena S, Susnik M, Ideo F, Schirru E, Cotti E. Prevalence of Apical Periodontitis in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Retrospective Clinical Study. J Endod. 2017;43:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chi YC, Chen JL, Wang LH, Chang K, Wu CL, Lin SY, Keller JJ, Bai CH. Increased risk of periodontitis among patients with Crohn's disease: a population-based matched-cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1437–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan CX, Brand HS, de Boer NK, Forouzanfar T. Gastrointestinal diseases and their oro-dental manifestations: Part 2: Ulcerative colitis. Br Dent J. 2017;222:53–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brito F, de Barros FC, Zaltman C, Carvalho AT, Carneiro AJ, Fischer RG, Gustafsson A, Figueredo CM. Prevalence of periodontitis and DMFT index in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:555–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brito F, Zaltman C, Carvalho AT, Fischer RG, Persson R, Gustafsson A, Figueredo CM. Subgingival microflora in inflammatory bowel disease patients with untreated periodontitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:239–245. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835a2b70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bunte K, Beikler T. Th17 Cells and the IL-23/IL-17 Axis in the Pathogenesis of Periodontitis and Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20143394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CY, Tseng KS, Liu JM, Chuang HC, Lien CH, Chen YC, Lai CY, Yu CP, Hsu RJ. Increased Risk of Ulcerative Colitis in Patients with Periodontal Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:30–44. doi: 10.1038/nri3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishida A, Inoue R, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Naito Y, Andoh A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12328-017-0813-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xun Z, Zhang Q, Xu T, Chen N, Chen F. Dysbiosis and Ecotypes of the Salivary Microbiome Associated With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and the Assistance in Diagnosis of Diseases Using Oral Bacterial Profiles. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1136. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin W, Ludvigsson JF, Liu Z, Roosaar A, Axéll T, Ye W. Inverse Association Between Poor Oral Health and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beaugerie L, Massot N, Carbonnel F, Cattan S, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Impact of cessation of smoking on the course of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2113–2116. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahid SS, Minor KS, Soto RE, Hornung CA, Galandiuk S. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1462–1471. doi: 10.4065/81.11.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Höie O, Wolters F, Riis L, Aamodt G, Solberg C, Bernklev T, Odes S, Mouzas IA, Beltrami M, Langholz E, Stockbrügger R, Vatn M, Moum B European Collaborative Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD) Ulcerative colitis: patient characteristics may predict 10-yr disease recurrence in a European-wide population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1692–1701. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blackwell J, Saxena S, Alexakis C, Bottle A, Cecil E, Majeed A, Pollok RC. The impact of smoking and smoking cessation on disease outcomes in ulcerative colitis: a nationwide population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:556–567. doi: 10.1111/apt.15390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang P, Hu J, Ghadermarzi S, Raza A, O’Connell D, Xiao A, Ayyaz F, Zhi M, Zhang Y, Parekh NK, Lazarev M, Parian A, Brant SR, Bedine M, Truta B, Hu P, Banerjee R, Hutfless SM. Smoking and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comparison of China, India, and the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:2703–2713. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5142-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johannsen A, Susin C, Gustafsson A. Smoking and inflammation: evidence for a synergistic role in chronic disease. Periodontol 2000. 2014;64:111–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang C, Shi G. Smoking and microbiome in oral, airway, gut and some systemic diseases. J Transl Med. 2019;17:225. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1971-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Capurso G, Lahner E. The interaction between smoking, alcohol and the gut microbiome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31:579–588. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanmaz B, Lamont G, Danacı G, Gogeneni H, Buduneli N, Scott DA. Microbiological and biochemical findings in relation to clinical periodontal status in active smokers, non-smokers and passive smokers. Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17:20. doi: 10.18332/tid/104492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–1794. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thia KT, Loftus EV, Jr, Sandborn WJ, Yang SK. An update on the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3167–3182. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park SH, Kim YJ, Rhee KH, Kim YH, Hong SN, Kim KH, Seo SI, Cha JM, Park SY, Jeong SK, Lee JH, Park H, Kim JS, Im JP, Yoon H, Kim SH, Jang J, Kim JH, Suh SO, Kim YK, Ye BD, Yang SK Songpa-Kangdong Inflammatory Bowel Disease [SK-IBD] Study Group. A 30-year Trend Analysis in the Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Songpa-Kangdong District of Seoul, Korea in 1986-2015. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:1410–1417. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi H, Matsui T, Hisabe T, Hirai F, Takatsu N, Tsurumi K, Kanemitsu T, Sato Y, Kinjyo K, Yano Y, Takaki Y, Nagahama T, Yao K, Washio M. Second peak in the distribution of age at onset of ulcerative colitis in relation to smoking cessation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1603–1608. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.