Abstract

Background

OSA, a common comorbidity in interstitial lung disease (ILD), could contribute to a worsened course if untreated. It is unclear if adherence to CPAP therapy improves outcomes.

Research Question

Does adherence to CPAP therapy improve outcomes in patients with concurrent interstitial lung disease and OSA?

Study Design and Methods

We conducted a 10-year retrospective observational multicenter cohort study, assessing adult patients with ILD who had undergone polysomnography. Subjects were categorized based on OSA severity into no/mild OSA (apnea-hypopnea index score < 15) or moderate/severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index score ≥ 15). All subjects prescribed and adherent to CPAP were deemed to have treated OSA. Cox regression models were used to examine the association of OSA severity and CPAP adherence with all-cause mortality risk and progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

Of 160 subjects that met inclusion criteria, 131 had OSA and were prescribed CPAP. Sixty-six patients (41%) had no/mild untreated OSA, 51 (32%) had moderate/severe untreated OSA, and 43 (27%) had treated OSA. Subjects with no/mild untreated OSA did not differ from those with moderate/severe untreated OSA in mean survival time (127 ± 56 vs 138 ± 93 months, respectively; P = .61) and crude mortality rate (2.9 per 100 person-years vs 2.9 per 100 person-years, respectively; P = .60). Adherence to CPAP was not associated with improvement in all-cause mortality risk (hazard ratio [HR], 1.1; 95% CI, 0.4-2.9; P = .79) or PFS (HR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.5-1.5; P = .66) compared with those that were nonadherent or untreated. Among subjects requiring supplemental oxygen, those adherent to CPAP had improved PFS (HR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; P = .03) compared with nonadherent or untreated subjects.

Interpretation

Neither OSA severity nor adherence to CPAP was associated with improved outcomes in patients with ILD except those requiring supplemental oxygen.

Key Words: CPAP, hypoxemia, interstitial lung disease, sleep apnea, sleep-disordered breathing

Abbreviations: AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; Dlco, diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; GAP-ILD, Gender-Age-Physiology - Interstitial Lung Disease subtype score; HR, hazard ratio; ILD, interstitial lung disease; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; PFS, progression-free survival

Mortality in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) has doubled over the last 3 decades in the United States.1 Use of antifibrotic medications in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), the most severe form of ILD, has been shown to slow the decline in lung function; however, they do not halt or reverse fibrosis.2,3 Furthermore, there is a paucity of Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies in numerous other forms of ILD. There is a need for an intervention that preserves lung function and mitigates disease progression that ultimately results in poor outcomes.

OSA is the most common respiratory disorder in the developing world4 and a common comorbidity in patients with ILD, occurring in up to 59% to 90% of patients with ILD.5,6 In a community-based study, moderate to severe OSA was associated with alveolar epithelial injury and extracellular matrix remodeling, and subclinical interstitial lung abnormalities on CT imaging.7 Although the exact pathogenic mechanisms linking OSA and ILD are yet to be elucidated, the coexistence of OSA in patients with ILD can lead to progression of ILD by several putative mechanisms. Repetitive forceful breathing against a completely occluded (obstructive apnea) or partially occluded upper airway (obstructive hypopnea) can lead to large negative swings in pleural pressure, thereby exerting regional lung stretch, analogous to ventilator-induced lung injury. In patients with parenchymal lung disease, obstructive apneas and hypopneas can lead to more profound oxygen desaturation. This degree of intermittent hypoxemia can potentiate oxidative stress, propagate systemic inflammation, and lead to progression of alveolar injury.8 Finally, gastroesophageal reflux disease can be exacerbated by OSA and can increase the risk of microaspiration in patients with ILD.9, 10, 11

CPAP therapy can effectively abolish obstructive apneas and hypopneas. One study from Greece included 55 patients with IPF with moderate to severe OSA treated with CPAP (37 adherent and 18 nonadherent to CPAP). After 24 months, only three patients in the nonadherent group had died, making the study underpowered to assess any meaningful association of CPAP use in patients with IPF with OSA.6 Therefore, there remains a paucity of data as to whether treatment of OSA with CPAP improves outcomes in patients with ILD.

In this investigation, we sought to retrospectively determine whether CPAP therapy is associated with long-term clinical outcomes in patients with coexistent OSA and ILD. We hypothesized that adherence to CPAP therapy in subjects with ILD with OSA is associated with decreased mortality and improvement in progression-free survival (PFS).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective observational multicenter cohort study of data from five US hospitals (one tertiary medical center [University of Chicago Hospitals] and four nontertiary medical centers [Evanston Hospital, Highland Park Hospital, Glenbrook Hospital, and Skokie Hospital]; institutional review board approved protocol Nos. IRB14163A, IRB16-1062, and IRB17-1617 [tertiary medical center], and EH17-025 [nontertiary medical centers]). We identified all adult subjects (≥ 18 years of age) assessed between January 2006 and July 2016 with a multidisciplinary or independently adjudicated ILD diagnosis based on clinical, pulmonary function, radiologic, and/or histopathologic evaluation according to current American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society criteria as previously described.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 An independent adjudication panel with ILD expertise (J. M. O., R. V., and I. N.) performed the determination of an adjudicated ILD diagnosis in a blinded fashion among all participants who had clinical information available for review as previously described.12,18 Cases were identified and pertinent clinical data were extracted from reviewed electronic charts with the assistance of the Clinical Research Data Warehouse maintained by the Center for Research Informatics at the University of Chicago (tertiary medical center) and the NorthShore HealthSystem Clinical Research Data Analytics unit (nontertiary medical centers).

Participants were included if they had undergone polysomnography for suspected OSA, had available polysomnogram documentation, and had a multidisciplinary or adjudicated diagnosis of chronic ILD. Among participants meeting inclusion criteria, we abstracted pertinent demographic, clinical, pulmonary function, polysomnogram, and oxygen supplementation data from the medical records documented at the time when polysomnography was performed. All sleep laboratories in our study used the same American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria for scoring apneas and hypopneas. Specifically, all laboratories scored hypopneas defined as a 30% reduction in amplitude of the nasal pressure transducer accompanied by either a ≥ 3% oxygen desaturation or a microarousal. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) for all subjects was determined. An a priori binary categorization of study participants was performed, which grouped subjects with AHI score < 15 as no/mild OSA and AHI score ≥ 15 as moderate/severe OSA. Subjects who had received a prescription for CPAP therapy and had obtained the device were assessed, and mean daily hours of CPAP use was determined. Data on CPAP use and adherence were obtained from the electronic medical records, sleep laboratory, and wireless data, which were collected per institutional protocol. CPAP efficacy was assessed in follow-up outpatient clinic sessions by implementing CPAP data downloads and daily usage. Patients who received a prescription for supplemental oxygen based on standard clinical practice and those on home oxygen therapy were determined from the electronic medical record. Participants deemed adherent to CPAP therapy (CPAP use of ≥ 4 h/night on ≥ 70% of days during the first 30 days of CPAP prescription) were categorized as having treated OSA.19 We chose the first 30 days of adherence because these data were available in all patients. Moreover, early patterns of CPAP use have been shown to correlate strongly with long-term CPAP adherence.20,21

To examine the association of CPAP adherence with lung function and PFS, CPAP adherence was treated as a binary variable, and duration of follow-up was treated as a continuous variable. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD and were compared using a two-tailed Student t test.

Categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. We used univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models for hazard ratio (HR) estimation and constructed a parsimonious Cox regression model with covariates selected a priori based on the study hypothesis. Selected covariates included hospital center, Gender-Age-Physiology - Interstitial Lung Disease subtype (GAP-ILD) score, ILD subtype, OSA severity, change in BMI, antifibrotic therapy, and time to polysomnography from ILD diagnosis. Center was controlled for as a random effect in analyses of multivariable outcome models.

Vital status was determined from review of medical records and social security death index. Subjects who had undergone lung transplantation were identified. Subjects with at least two pulmonary function tests performed > 90 days apart were identified. Follow-up time was censored on December 31, 2018, or when a participant was lost to follow-up. PFS time was defined as the time from polysomnogram performance to first occurrence of the following: a decrease of ≥ 10% in FVC % predicted, a decrease of ≥ 15% in diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (Dlco) % predicted, death, lung transplantation, loss to follow-up, or end of study period. PFS was evaluated over the first 80 months after polysomnogram performance. Additionally, sensitivity analyses for our models using a propensity score approach were performed in the cohort to predict the conditional probability for an individual to receive CPAP treatment. Covariates included in our propensity score model were as follows: hospital center, GAP-ILD score, OSA severity, change in BMI, antifibrotic therapy, and time to polysomnography from ILD diagnosis. Inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to estimate the average treatment effect on time-to-event outcomes.22 Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier survival estimator. The change from baseline FVC % predicted was determined for all participants with FVC data at 12, 24, and 36 months. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05 (R.15; StataCorp).

Results

One hundred and sixty participants met criteria for inclusion during the study period. The mean age was 64 years, with a mean BMI of 33.5 kg/m2, and 44% were men (Table 1 e-Table 1). Most were non-Hispanic white subjects (58%), and 45% reported a history of smoking. Coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and gastroesophageal reflux were prevalent in the cohort (18%, 27%, and 41%, respectively). The mean FVC % predicted and Dlco % predicted were 64% and 53%, respectively. Within the cohort, subjects with IPF constituted most participants (33%), followed by unclassifiable ILD (22%), connective tissue disease-associated ILD (18%), interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (14%), and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (5%). The median GAP-ILD score for the entire cohort was 3 (interquartile range, 1-4).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristics | All Patients (N = 160) |

No/Mild Untreated OSA (n = 66) |

Moderate to Severe Untreated OSA (n = 51) | Treated OSA (n = 43) |

P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, y | 64.4 ± 11.5 | 61.3 ± 11.8 | 65.7 ± 9.3 | 67.5 ± 12.4 | .013 |

| Male sex | 70 (43.8) | 19 (28.8) | 30 (58.8) | 21 (48.8) | .004 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 81 (57.5) | 30 (53.6) | 20 (43.5) | 31 (79.5) | .039 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33.5 ± 7.7 | 32.0 ± 7.6 | 34.5 ± 7.1 | 34.6 ± 8.5 | .12 |

| Ever smoker | 66 (44.9) | 27 (46.6) | 23 (46.9) | 16 (40.0) | .77 |

| Diabetes | 5 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (16.7) | 2 (14.3) | .08 |

| CAD | 23 (18.4) | 5 (9.6) | 7 (18.9) | 11 (30.6) | .045 |

| CHF | 43 (26.9) | 14 (21.2) | 17 (33.3) | 12 (27.9) | .34 |

| GERD | 58 (40.9) | 29 (50.0) | 15 (33.3) | 14 (35.9) | .18 |

| ILD characteristics | |||||

| ILD subtype | |||||

| IPF | 52 (32.5) | 22 (33.3) | 16 (31.4) | 14 (32.6) | .98 |

| IPAFs | 22 (13.8) | 10 (15.2) | 8 (15.7) | 4 (9.3) | .61 |

| CHP | 8 (5.0) | 1 (1.5) | 4 (7.8) | 3 (7.0) | .23 |

| CTD-ILD | 29 (18.1) | 16 (24.2) | 10 (19.6) | 3 (7.0) | .07 |

| Unclassifiable | 35 (21.9) | 8 (12.1) | 11 (21.6) | 16 (37.2) | .008 |

| GAP-ILD score, median (IQR) | 3 (1-4) | 3 (1-4) | 3 (2-5) | 3 (2-5) | .18 |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | 94 (64.4) | 40 (69.0) | 26 (54.2) | 28 (70.0) | .20 |

| Antifibrotic therapy | 20 (13.6) | 7 (12.1) | 7 (14.3) | 6 (15.0) | .90 |

| HRCT scan honeycombing | 37 (26.4) | 14 (25.0) | 17 (37.8) | 6 (15.4) | .06 |

| PA diameter | 30.0 ± 4.9 | 28.9 ± 4.7 | 31.2 ± 5.6 | 30.2 ± 3.7 | .16 |

| FVC | 63.7 ± 17.1 | 60.7 ± 14.6 | 65.8 ± 19.0 | 65.8 ± 18.2 | .20 |

| FEV1 | 70.9 ± 20.6 | 66.3 ± 16.7 | 73.3 ± 22.8 | 74.8 ± 22.4 | .09 |

| Dlco | 53.1 ± 19.6 | 53.0 ± 19.2 | 53.5 ± 20.8 | 52.8 ± 19.1 | .98 |

| CRP | 10.2 ± 13.3 | 12.4 ± 16.2 | 10.1 ± 13.1 | 6.4 ± 4.4 | .43 |

| PSG characteristics | |||||

| ILD to PSG interval, mo | 17.7 ± 39.4 | 23.1 ± 36.5 | 17.6 ± 41.2 | 9.5 ± 41.1 | .22 |

| Δ BMI (in ILD to PSG interval) | 0.4 ± 3.2 | 0.9 ± 3.1 | 0.3 ± 3.6 | 0.4 ± 2.6 | .14 |

| AHI | 28.9 ± 30.8 | 6.7 ± 4.3 | 49.7 ± 33.3 | 38.4 ± 29.2 | < .0001 |

| 3% ODI | 28.5 ± 39.4 | 6.5 ± 6.3 | 47.6 ± 55.1 | 47.6 ± 29.1 | < .0001 |

| T90 | 20.9 ± 29.7 | 9.9 ± 19.4 | 33.2 ± 36.7 | 23.2 ± 27.8 | .0001 |

| Spo2 nadir | 80.4 ± 8.5 | 84.8 ± 5.7 | 76.1 ± 8.5 | 78.8 ± 9.1 | < .0001 |

| REM AHI | 33.0 ± 28.6 | 13.8 ± 13.2 | 57.4 ± 28.0 | 48.1 ± 23.9 | < .0001 |

| NREM AHI | 19.5 ± 25.2 | 5.6 ± 4.4 | 36.6 ± 30.5 | 33.8 ± 28.5 | < .0001 |

| Central apnea index (per hour) | 0.9 ± 3.9 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 5.3 | 1.1 ± 4.6 | .10 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale score | 8.3 ± 4.4 | 8.6 ± 4.4 | 7.8 ± 4.4 | 8.3 ± 4.5 | .67 |

| CPAP prescribed | 131 (82) | 37 (56) | 51 (100) | 43 (100) | < .0001 |

| CPAP received at home | 100 (62.5) | 16 (24.4) | 41 (80.4) | 43 (100) | < .0001 |

| Mean CPAP use, h/nightb | 3.7 ± 3.3 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.1 ± 1.4 | 7.0 ± 1.7 | < .0001 |

| Oxygen supplementation | |||||

| No supplemental oxygen requirement | 105 (65.6) | 46 (69.7) | 29 (56.9) | 30 (69.8) | .28 |

| Require supplemental oxygen | 55 (34.4) | 20 (30.3) | 22 (43.1) | 13 (30.2) | … |

Categorical variables are presented as No. (%), continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD, and all other values are as otherwise listed. AHI = apnea hypopnea index; CAD = coronary artery disease; CHF = congestive heart failure; CHP = chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; CRP = C-reactive protein; CTD-ILD = connective tissue disease associated-ILD; Dlco = diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; GAP-ILD = Gender-Age-Physiology - Interstitial Lung Disease subtype score; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; HRCT = high-resolution CT; ILD = interstitial lung disease; IPAF = interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; IQR = interquartile range; NREM = non-rapid eye movement; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; PA = pulmonary artery; PSG = polysomnogram; REM = rapid eye movement; SpO2 = peripheral capillary oxygen saturation; T90 = total sleep time with oxygen saturation < 90%.

P value comparing no/mild untreated OSA, moderate to severe untreated OSA, and treated OSA. Exception for participants: smoking status, n = 147; diabetes, n = 62; CAD, n = 125; GERD, n = 142; FVC, n = 154; FEV1, n = 138; Dlco, n = 146; CRP, n = 54; immunosuppressive therapy, n = 146; antifibrotic therapy, n = 147; oxygen requirement in daytime, n = 147; radiographic honeycombing, n = 140; PA size, n = 84; and other ILD, n = 13.

Mean CPAP use only in patients who received a CPAP device at home.

Performance of polysomnography occurred within 18 ± 39 months after ILD diagnosis, during which the mean change in BMI was 0.4 ± 3.2 kg/m2. Among the cohort of 160 patients, 86 had moderate to severe OSA (AHI score ≥ 15), of which 78 (91%) underwent in-laboratory positive airway pressure titration. Of the 47 patients with mild OSA (AHI score < 15), 21 (45%) underwent in-laboratory titration. Twenty-seven patients did not have OSA (AHI score < 5). CPAP was prescribed in 131 of 160 patients (82%). Of these, 99 (76%) underwent in-laboratory positive airway pressure titration. The remaining 32 patients were prescribed empirical auto-positive airway pressure settings. OSA was deemed clinically significant to warrant therapy in most subjects (n = 131; 82%) because of the presence of moderate to severe OSA, or in cases of mild OSA because of symptoms, and CPAP therapy was prescribed. Therefore, of the 131 patients for whom CPAP was prescribed, 100 patients accepted the prescription and received it at home (Table 1).

Of these subjects, most received the device for home use (n = 100; 63%). Few patients overall were adherent to CPAP therapy (n = 43; 27%). Among untreated or nonadherent subjects, OSA was moderate to severe in 32% (n = 51), whereas the remainder had mild or no OSA (n = 66, 41%). Mean AHI in subjects with moderate to severe untreated OSA was greater than that of untreated subjects with mild or no OSA (49.7 ± 33.3 vs 6.7 ± 4.3 events/h, respectively; P < .0001). Mean duration of CPAP use (h/night) in subjects that were adherent to therapy was greater than that among the 41 subjects with untreated moderate to severe OSA who received CPAP, and among the 16 subjects with untreated mild OSA who received CPAP (7.0 ± 1.7 vs 1.1 ± 1.4 vs 1.5 ± 1.8 h/night, respectively; P < .0001). Most patients (n = 105; 66%) had no requirement for supplemental oxygen. The prevalence of CPAP adherent subjects that required supplemental oxygen was similar to that among nonadherent or untreated subjects (n = 13, 30% vs n = 42, 36%, respectively; P = .50).

Overall, 26 patients with ILD (16.3%) died, 9 (5.6%) underwent lung transplantation and PFS events occurred in 98 patients (61.3%) during the follow-up period. In univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2), key predictors of increased all-cause mortality risk among those that underwent polysomnography included male sex (HR, 3.03; 95% CI, 1.33-6.91; P = .008), presence of congestive heart failure (HR, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.42-6.85; P = .005), need for supplemental oxygen (HR, 2.89; 95% CI, 1.30-6.42; P = .009), and each unit increase in the GAP-ILD score (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.14-1.72; P = .001). Each percentage increase in Dlco from the mean was associated with decreased mortality risk (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99; P = .002). Each unit increase in the number of central apneas, the number of mixed apneas, and the central apnea index also predicted increased all-cause mortality risk (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03; P = .004; HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.02-1.07; P = .034; and HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03-1.13; P = .003, respectively). The association between central apnea index and all-cause mortality persisted after adjusting for covariates (P = .02). In contrast, AHI, percent of total sleep time with oxygen saturation < 90%, and number of hours per night adherent to CPAP therapy were not significant predictors of survival in univariate analysis.

Table 2.

Univariate Predictors of Outcomes Among Subjects With ILD Undergoing PSG for Sleep-Disordered Breathing

| Characteristic | All-Cause Mortality |

Progression-Free Survival |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| ILD demographic features | ||||||

| Male | 3.03 | 1.33-6.91 | .008 | 1.45 | 0.96-2.18 | .078 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.98-1.05 | .548 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.00 | .136 |

| BMI | 0.97 | 0.91-1.02 | .231 | 0.99 | 0.96-1.01 | .381 |

| CHF | 3.12 | 1.42-6.85 | .005 | 0.77 | 0.48-1.23 | .269 |

| Oxygen requirement | 2.89 | 1.30-6.42 | .009 | 1.30 | 0.86-2.00 | .210 |

| HRCT scan honeycombing | 2.18 | 0.98-4.90 | .058 | 1.70 | 1.07-2.69 | .023 |

| FVC | 1.00 | 0.98-1.02 | .932 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.00 | .025 |

| Dlco | 0.96 | 0.94-0.99 | .002 | 0.98 | 0.97-0.99 | .001 |

| GAP-ILD score | 1.40 | 1.14-1.72 | .001 | 1.13 | 1.02-1.25 | .019 |

| PSG features | ||||||

| AHI | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | .276 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | .712 |

| T90, min | 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | .220 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | .970 |

| T90 (% of total sleep time) | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | .348 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | .842 |

| CPAP adherence | 1.23 | 0.54-2.80 | .629 | 0.97 | 0.91-1.04 | .378 |

| Central apneas | 1.02 | 1.01-1.03 | .004 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | .880 |

| Central apnea index | 1.08 | 1.03-1.13 | .003 | 1.00 | 0.98-1.03 | .748 |

| Obstructive apneas | 1.00 | 0.98-1.02 | .907 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | .632 |

| Obstructive apnea index | 1.00 | 0.93-1.09 | .923 | 0.47 | 0.03-6.87 | .578 |

| Mixed apneas | 1.02 | 1.02-1.07 | .034 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.02 | .567 |

| Mixed apnea index | 1.09 | 0.99-1.21 | .071 | 0.98 | 0.92-1.04 | .448 |

| Hypopneas | 1.00 | 0.98-1.00 | .151 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | .758 |

| Hypopnea index | 0.98 | 0.95-1.02 | .378 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | .921 |

HR = hazard ratio. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Similarly, univariate predictors of worsened PFS included radiographic presence of honeycombing on chest CT scan (HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.07-2.69; P = .023) and each unit increase in the GAP-ILD score (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.25; P = .019). Each percentage increase in FVC and Dlco was associated with decreased mortality risk (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97-1.00; P = .025, and HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97-0.99; P = .001, respectively). AHI, central apneas, percent of total sleep time with oxygen saturation < 90%, and number of hours per night adherent to CPAP therapy were not significant predictors of PFS in univariate analysis.

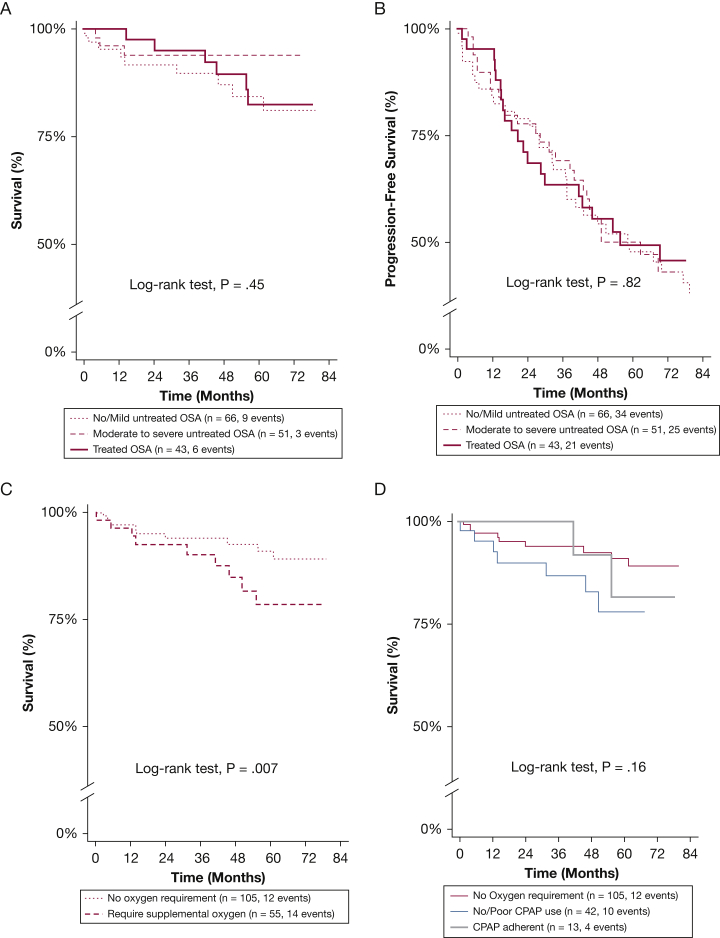

When comparing the cohort based on severity of OSA and adherence to CPAP therapy, the mean survival time did not differ for subjects that were adherent to CPAP therapy when compared with subjects with untreated moderate to severe OSA, and those with untreated mild or absent OSA (140 ± 76 vs 138 ± 93 vs 127 ± 56 months; P = .61, respectively) (Table 3). Also, adherence to CPAP therapy was not associated with improvement in all-cause mortality risk (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.4-2.9; P = .79) or PFS (HR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.5-1.5; P = .66) when compared with those that were nonadherent or untreated with CPAP, even after adjustment for center, GAP-ILD score, OSA severity, change in BMI, antifibrotic therapy, and time to polysomnography from ILD diagnosis (HR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.3-2.0; P = .58; and HR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.4-1.2; P = .20, respectively) (Figs 1A, 1B). Because some studies suggest that more sleepy OSA phenotypes may be associated with increased cardiovascular complications, we explored the association of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale with outcomes in the cohort. Epworth Sleepiness Scale was not significantly associated with either all-cause mortality or PFS in all unadjusted and adjusted models. Additional sensitivity analyses exploring the effects of OSA severity and CPAP adherence separately and also evaluating the interaction between them demonstrated no significant association between OSA severity and CPAP adherence with all-cause mortality and PFS (e-Table 2). Furthermore, propensity-matched analyses demonstrated that adherence to CPAP therapy was not associated with improvement in all-cause mortality risk or PFS in all models (e-Tables 3, 4).

Table 3.

Outcomes Compared by Severity of OSA

| Characteristic | No/Mild Untreated OSA (n = 66) |

Moderate to Severe Untreated OSA (n = 51) | Treated OSA (n = 43) |

P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival time, mean ± SD, mo | 127 ± 56 | 138 ± 93 | 140 ± 76 | .61 |

| All-cause mortalityb | ||||

| Crude mortality rate (per 100 person-years) | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.5 | .60 |

| Unadjusted model | ||||

| Moderate to severe untreated | … | 0.9 (0.3-2.3) | … | .75 |

| Treated | … | … | 1.1 (0.4-2.9) | .79 |

| Adjusted HR | ||||

| Moderate to severe untreated | … | 0.5 (0.2-1.5) | … | .23 |

| Treated | … | … | 0.8 (0.3-2.0) | .58 |

| Progression-free survivalc,d | ||||

| Unadjusted HR | ||||

| Moderate to severe untreated | … | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) | … | .57 |

| Treated | … | … | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | .66 |

| Adjusted HR | ||||

| Moderate to severe untreated | … | 0.8 (0.5-1.5) | … | .55 |

| Treated | … | … | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | .20 |

| Lung transplantation, No. (%) | 5 (7.6) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (4.7) | .59 |

Values are HR (95% CI) or as otherwise indicated. See Table 1 and 2 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

HR compared with no/mild untreated OSA.

Multivariable model adjusted for GAP-ILD score and OSA severity.

Progression-free survival over first 7 years of study period.

Multivariable model adjusted for hospital center, GAP-ILD score, OSA severity, change in BMI, antifibrotic therapy, and time to PSG from ILD diagnosis.

Figure 1.

A-D, Predictors of mortality among subjects with interstitial lung disease (ILD) who performed polysomnography. A, All-cause mortality categorized by OSA severity and treatment (adherence to CPAP therapy). B, Progression-free survival pattern categorized by OSA severity and treatment. Progression-free survival assessed over first 7 y of study period. C, All-cause mortality categorized by requirement for oxygen supplementation among subjects with ILD who performed polysomnography. Those requiring oxygen supplementation had worse mortality (hazard ratio, 2.89; 95% CI, 1.30-6.42; P = .009) when compared with those without supplemental oxygen requirement. D, When evaluating association of all-cause mortality with CPAP therapy, mortality risk did not differ between CPAP adherent subjects (≥ 4 h/d; n = 13) and CPAP nonadherent subjects (< 4 h/d; n = 42).

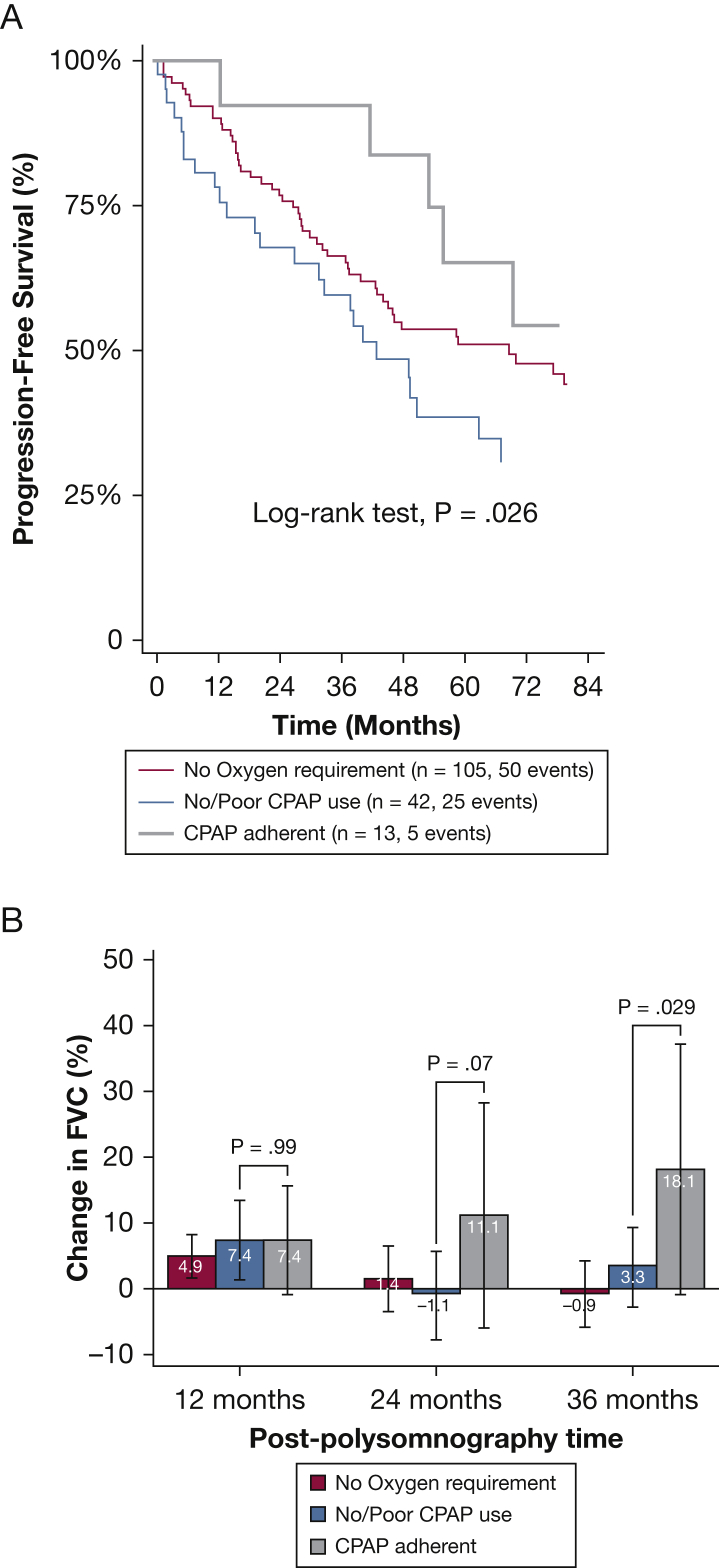

Because key indices of oxygenation were important predictors of mortality, we categorized the cohort into those with supplemental oxygen requirement (n = 55; 34%) and those without (n = 105; 66%) (e-Fig 1, e-Table 1), and performed a subgroup analysis assessing the value of adherence to CPAP therapy within these populations (Table 4). The mean survival time in 13 subjects adherent to CPAP therapy and requiring supplemental oxygen was shorter when compared with subjects without supplemental oxygen requirement and those nonadherent to CPAP therapy requiring supplemental oxygen (100 ± 55 vs 159 ± 72 vs 109 ± 60 months, respectively; P < .0001). Subjects without a requirement for supplemental oxygen had improved mortality hazard in univariate analysis (HR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1-0.8; P = .015) and PFS (HR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-1.0; P = .06) when compared with those that were nonadherent or untreated with CPAP, but not after multivariable adjustment (Fig 1C, Table 4). Interestingly, when compared with those who required supplemental oxygen that were nonadherent or untreated with CPAP, subjects adherent to CPAP therapy had similar risk of unadjusted and adjusted all-cause mortality (HR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.3-3.0; P = .93; and HR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.2-2.2; P = .47, respectively) (Fig 1D); however, those adherent to CPAP therapy had improved PFS, on unadjusted and adjusted analyses (HR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1-0.8; P = .017; and HR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9; P = .03, respectively), and in propensity-score matched analyses (e-Table 5, Fig 2A). When assessing the change from baseline FVC among subjects requiring oxygen supplementation, there was no difference at 12 months between subjects adherent to CPAP therapy and those that were nonadherent or untreated with CPAP (7.4% vs 7.4%, respectively; P = .99). However, the change from baseline FVC was better in subjects that were adherent to CPAP therapy at 24 months (11.1% vs −1.1%; P = .07) and 36 months (18.1% vs 3.3%; P = .029) when compared with subjects that were nonadherent or untreated with CPAP, respectively (Fig 2B).

Table 4.

Outcomes Among Subjects Compared by Supplemental Oxygen Requirement

| Characteristic | No Supplemental Oxygen Requirement (n = 105) |

Require Supplemental Oxygen |

P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CPAP Use or Nonadherent (n = 42) | Adherent to CPAP Use (n = 13) | |||

| Survival time, mean ± SD, mo | 159 ± 72 | 109 ± 60 | 100 ± 55 | < .0001 |

| All-cause mortalityb | ||||

| Crude mortality rate (per 100 person-years) | 2.1 | 5.3 | 5.1 | .06 |

| Unadjusted HR | ||||

| Not requiring supplemental oxygen | 0.3 (0.1-0.8) | … | … | .015 |

| CPAP adherent | … | … | 0.9 (0.3-3.0) | .93 |

| Adjusted HRc | ||||

| Not requiring supplemental oxygen | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) | … | … | .11 |

| CPAP adherent | … | … | 0.6 (0.2-2.2) | .47 |

| Progression-free survivalc,d | ||||

| Unadjusted HR | ||||

| Not requiring supplemental oxygen | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | … | … | .06 |

| CPAP adherent | … | … | 0.3 (0.1-0.8) | .017 |

| Adjusted HR | ||||

| Not requiring supplemental oxygen | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | … | … | .37 |

| CPAP adherent | … | … | 0.3 (0.1-0.9) | .03 |

| Lung transplantation, No. (%) | 6 (5.7) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (7.7) | .88 |

Values are HR (95% CI) or as otherwise indicated. See Table 1 and 2 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

HR compared with subjects with no supplemental oxygen requirement.

Multivariable model adjusted for GAP-ILD score and OSA severity.

Multivariable model adjusted for hospital center, GAP-ILD score, OSA severity, change in BMI, antifibrotic therapy, and time to PSG from ILD diagnosis.

Progression-free survival over first 7 years of study period.

Figure 2.

A-B, Association of CPAP use with outcomes in subjects with ILD who performed polysomnography. A, Progression-free survival (PFS) pattern by CPAP use. Among subjects requiring oxygen supplementation, those with good CPAP adherence (≥ 4 h/d; n = 13) had improved PFS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.23; 95% CI, 0.08-0.69; P = .009) when compared with those with poor CPAP adherence (< 4 h/d; n = 42). Comparatively, PFS was marginally improved in those without supplemental oxygen requirement (n = 105; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.38-1.01; P = .06). B, Adjusted change from baseline in FVC % predicted at 1, 2, and 3 y post-polysomnography depicts preservation of lung volumes among those with good CPAP adherence. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that adherence to CPAP therapy is not associated with improved all-cause mortality or PFS in most patients with coexistent ILD and OSA. However, in a secondary analysis of the study, our results suggested that in the subpopulation requiring oxygen supplementation, CPAP therapy is associated with improved PFS and preservation of FVC, findings that would need to be prospectively validated. If confirmed in larger prospective studies, this intervention could have a paradigm-shifting effect in subjects with hypoxemia, ILD, and OSA given that many pharmacotherapeutic agents tested in ILD have so far yielded disappointing results.

Patients with OSA experience hundreds of obstructive apneas and hypopneas every night during the sleep period. These forceful inspiratory efforts against a completely (apnea) or partially (hypopnea) occluded upper airway lead to repetitive, prolonged airflow cessation and intermittent hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Furthermore, OSA causes significant swings in pleural pressure, thereby exerting peripheral tractional stress on the lungs, an injury that may be analogous to what occurs during positive pressure ventilation.23 In patients with hypoxemia receiving supplemental oxygen, CPAP therapy effectively abolishes the upper airway obstruction during sleep, decreases stress-induced inflammation, and relieves alveolar hypoxia by permitting unrestricted influx of air into the alveoli. CPAP can maintain upper airway patency, relieve intermittent hypoxemia/hypercapnia and microarousal caused by obstructive apneas and hypopneas, improve end-expiratory lung volume, and make the lungs less prone to alveolar collapse, potentially leading to preservation of lung volumes, better pulmonary function, and improved quality of life. This is of critical importance in ILD, given that untreated moderate to severe OSA is a modifiable risk factor, which could be significantly improved when treated with CPAP during sleep.

In symptomatic patients with OSA, CPAP therapy can improve sleep quality, reduce daytime sleepiness, and improve quality of life. However, we think there is clinical equipoise as to whether CPAP therapy can improve ILD-centric outcomes in patients with ILD and OSA overlap. For example, several large randomized controlled studies have shown no improvement in cardiovascular mortality in patients with moderate to severe OSA treated with CPAP.24, 25, 26 Therefore, it stands to reason that CPAP treatment of OSA would be unlikely to improve cardiovascular mortality in patients with ILD. Whether CPAP therapy can improve respiratory-related mortality and progression of ILD requires further investigation. Our finding of an association between central apneas and all-cause mortality remains unclear, particularly that the overall central apnea index was very low. However, central apneas may be a marker of cardiovascular disease because its prevalence increases in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and in patients with atrial fibrillation.27,28

Although we did not find an independent association between sleep hypoxemia and outcomes in the entire cohort, an Australian study of 92 patients with ILD reported an association between sleep hypoxemia and worse survival and PFS.5 One might assume that supplemental oxygen can be easily added to CPAP in patients with ILD and OSA who experience significant hypoxemia during sleep. However, compared with nasal cannula, CPAP can worsen oxygen delivery by not allowing supplied oxygen to blend adequately with the air because of turbulent flow generated by CPAP.29,30 As such, caution needs to be exercised when oxygen is added to CPAP, and close monitoring is necessary to ensure adequate oxygen delivery during sleep while wearing CPAP.

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective nature of this investigation allows for assessment of association but not causation. Pulmonary function testing data were sparse beyond 36 months after initial polysomnogram performance. We could not ascertain the cause of mortality in most patients. Also, because of the low event rates and the small number of subjects adherent to CPAP, our study was underpowered to explore the associations of interest fully, and this may have led to negative results. Given the low frequency of deaths within the study period, we elected to also focus on disease progression in addition to all-cause mortality. Also, given the retrospective nature of the study, we were unable to ascertain specific actions taken at each clinic and by each sleep specialist to address noncompliance with CPAP. Finally, not all patients with ILD who underwent polysomnography had OSA. Notwithstanding these limitations, our study has several noteworthy strengths. The diverse cohort was derived from five different medical centers and is the largest cohort of patients with multidisciplinary or independently adjudicated ILD undergoing in-laboratory polysomnography to date. Moreover, we had a wide range of OSA severity, and short-term CPAP adherence was objectively verified in all patients who received CPAP therapy at home. Short-term CPAP adherence has been shown to correlate strongly with long-term CPAP adherence.20,21 In addition to examining all-cause mortality, we also explored PFS. Therefore, the robust polysomnogram data accrued from these subjects at multiple hospital centers over time lend credence to its generalizability.

In summary, OSA is common in ILD. Still, neither its severity nor adherence to CPAP is associated with improved outcomes, except possibly among the subset who require supplemental oxygen, where the association deserves further exploration in larger, randomized controlled studies. This novel finding may justify and inform the design of future prospective clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of therapeutic CPAP use on clinical outcomes in patients with ILD.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: A. A., J. M. N., D. Z., B. C., N. G., J. M. O., I. N., R. V., T. J. K., S. K. B., M. E. S., and B. M. provided final approval of the submitted manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work. A. A., J. M. N., and B. M. contributed to conception and design. A. A., J. M. N., D. Z., B. C., N. G., J. M. O., I. N., R. V., T. J. K., S. K. B., M. E. S., and B. M. contributed to acquisition of data for the work. A. A. and B. M. contributed to analysis and interpretation. A. A., J. M. N., D. Z., M. E. S., and B. M. contributed to drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content. A. A., J. M. N., D. Z., B. C., N. G., J. M. O., I. N., R. V., T. J. K., S. K. B., M. E. S., and B. M. contributed to critical revision for important intellectual content.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: A. A. has received speaking and advisory board fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, and is supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL146942). J. M. O. has received speaking and advisory board fees from Genentech and Boehringer Ingelheim, and is supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL138190). R. V. has received a grant from Genentech to study the genomics of autoimmune interstitial lung diseases. I. N. has received honoraria for advisory boards with Boehringer Ingelheim, InterMune, and Anthera within the last 12 months related to IPF; has received speaking honoraria from GSK and receives consulting fees for Immuneworks; has study contracts with the NIH, Stromedix, Sanofi, and BI for the conduct of clinical trials in IPF; and is supported by an award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL130796). M. E. S. has received institutional funding for interstitial lung disease research from the NIH, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Galapagos, and Novartis; and has received honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim for educational product development, and an advisory board and editorial support. None declared (J. M. N., D. Z., B. C., N. G., T. J. K., S. K. B., B. M.).

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Figure and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

Drs Adegunsoye and Neborak contributed equally to this manuscript.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants K23HL146942, K23HL138190, R01HL130796].

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Dwyer-Lindgren L., Bertozzi-Villa A., Stubbs R.W. Trends and patterns of differences in chronic respiratory disease mortality among US counties, 1980-2014. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1136–1149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King T.E., Jr., Bradford W.Z., Castro-Bernardini S. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richeldi L., du Bois R.M., Raghu G. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2071–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjafield A.V., Ayas N.T., Eastwood P.R. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(8):687–698. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troy L.K., Young I.H., Lau E.M.T. Nocturnal hypoxaemia is associated with adverse outcomes in interstitial lung disease. Respirology. 2019;24(10):996–1004. doi: 10.1111/resp.13549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mermigkis C., Bouloukaki I., Antoniou K. Obstructive sleep apnea should be treated in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(1):385–391. doi: 10.1007/s11325-014-1033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J.S., Podolanczuk A.J., Borker P. Obstructive sleep apnea and subclinical interstitial lung disease in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(12):1786–1795. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201701-091OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adegunsoye A., Balachandran J. Inflammatory response mechanisms exacerbating hypoxemia in coexistent pulmonary fibrosis and sleep apnea. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:510105. doi: 10.1155/2015/510105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghu G., Freudenberger T.D., Yang S. High prevalence of abnormal acid gastro-oesophageal reflux in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(1):136–142. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00037005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raghu G., Pellegrini C.A., Yow E. Laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (WRAP-IPF): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(9):707–714. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedard Methot D., Leblanc E., Lacasse Y. Meta-analysis of gastroesophageal reflux disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2019;155(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adegunsoye A., Oldham J.M., Bellam S.K. African-American race and mortality in interstitial lung disease: a multicentre propensity-matched analysis. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(6):1800255. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00255-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travis W.D., Costabel U., Hansell D.M. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respirat Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respirat Crit Care Med. 2002;165(2):277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer A., Antoniou K.M., Brown K.K. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society research statement: interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(4):976–987. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00150-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghu G., Collard H.R., Egan J.J. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respirat Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raghu G., Rochwerg B., Zhang Y. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the 2011 clinical practice guideline. Am J Respirat Crit Care Med. 2015;192(2):e3–e19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adegunsoye A., Oldham J.M., Bonham C. Prognosticating outcomes in interstitial lung disease by mediastinal lymph node assessment: an observational cohort study with independent validation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(6):747–759. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0761OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang D., Chang J.W., Benjafield A.V. Effect of telemedicine education and telemonitoring on continuous positive airway pressure adherence. The Tele-OSA randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(1):117–126. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0582OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budhiraja R., Parthasarathy S., Drake C.L. Early CPAP use identifies subsequent adherence to CPAP therapy. Sleep. 2007;30(3):320–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chai-Coetzer C.L., Luo Y.M., Antic N.A. Predictors of long-term adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease in the SAVE study. Sleep. 2013;36(12):1929–1937. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin P.C., Stuart E.A. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34(28):3661–3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bijaoui E.L., Champagne V., Baconnier P.F., Kimoff R.J., Bates J.H. Mechanical properties of the lung and upper airways in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(8):1055–1061. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.8.2107144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McEvoy R.D., Antic N.A., Heeley E. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):919–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbe F., Duran-Cantolla J., Sanchez-de-la-Torre M. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on the incidence of hypertension and cardiovascular events in nonsleepy patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307(20):2161–2168. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peker Y., Glantz H., Eulenburg C., Wegscheider K., Herlitz J., Thunstrom E. Effect of positive airway pressure on cardiovascular outcomes in coronary artery disease patients with nonsleepy obstructive sleep apnea. The RICCADSA randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(5):613–620. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201601-0088OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Javaheri S., Dempsey J.A. Central sleep apnea. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(1):141–163. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javaheri S., Barbe F., Campos-Rodriguez F. Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(7):841–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoder E.A., Klann K., Strohl K.P. Inspired oxygen concentrations during positive pressure therapy. Sleep Breath. 2004;8(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11325-004-0001-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz A.R., Kacmarek R.M., Hess D.R. Factors affecting oxygen delivery with bi-level positive airway pressure. Respir Care. 2004;49(3):270–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.