Abstract

The present study examined mechanisms of change in dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) skills group and positive psychotherapy (PPT) group intervention, two treatments that have previously been shown to be effective at reducing symptoms of BPD and depression over a 12-week treatment protocol within the context of a college counseling center (Uliaszek et al., 2016). The present study is secondary data analysis of that trial. We hypothesized that change in dysfunctional coping skills use would be a specific mechanism for DBT, while change in functional coping skills use and therapeutic alliance would be mechanisms of change for both treatments. Fifty-four participants completed self-report and interview-based assessments at pretreatment, weeks 3, 6, 9, and posttreatment. Path models examined the predictive power of the mechanisms in predicting outcome; the moderating effect of group membership was also explored. Dysfunctional coping skills use across the course of treatment was a significant mechanism of change for BPD and depression for the DBT group, but not the PPT group. Conversely, therapeutic alliance was a significant mechanism of change for the PPT group, but not the DBT group. Findings highlight the importance of each mechanism during mid-to late-treatment specifically.

Keywords: Dialectical behavior therapy, Positive psychotherapy, College counseling center, Mechanism, Coping, Therapeutic alliance

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an empirically-supported treatment for suicide, non-suicidal self-injury, and symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD; e.g., Koons et al., 2001; Linehan et al., 2006). Derived from cognitive-behavioral therapy, it includes a dialectical philosophy, radical behaviorism, and mindfulness (Linehan, 1993). While this literature continues to grow exponentially with adapted versions of DBT targeting specific ages (e.g., Miller, Rathus, & Linehan, 2006), psychiatric populations (e.g., Harned, Korslund, & Linehan, 2014; Lynch, Morse, Mendelson, & Robins, 2003), and settings (e.g., Pistorello, Fruzzetti, MacLane, Gallop, & Iverson, 2012), there is a paucity of evidence regarding mechanisms underlying the treatment.

The present study involves secondary data analysis from a randomized control trial (Uliaszek, Rashid, Williams, & Gulamani, 2016) that demonstrated that both DBT and a comparison group treatment (positive psychotherapy group treatment; PPT) resulted in large effect size changes in self-report and diagnostic-interview assessed BPD and depressive symptoms. However, it is unclear whether the mechanism of change differed across treatments. Elucidating treatment mechanism is important because it provides 1) information for improving treatment efficacy, 2) insight into necessary and sufficient conditions for change within a set of symptoms, and 3) proof of theory for a specific intervention.

1. Mechanisms of change in psychotherapeutic outcomes

Mechanisms of change are the processes through which change occurs. The study of mechanisms in psychotherapy aids in optimizing treatments by allowing for increased focus on the areas known to contribute most to the change process. This is also particularly relevant to dissemination of evidence-based treatments into real-world settings where complex treatments such as DBT may need to be adapted. Kazdin (2007) explains that in order to translate research into practice one must know, “what is needed to make treatment work, what are the optimal conditions, and what components must not be diluted to achieve change” (p. 4). Mechanisms of change also allow for better understanding of the factors that are most associated with change in a particular clinical population.

A recent review of mechanisms in evidence-based treatments for BPD located 12 papers related to DBT and two related to CBT (Rudge, Feigenbaum, & Fonagy, 2017). These authors found three broad themes of mechanisms of change in the DBT literature: 1) emotion regulation and self-control, 2) skills use, and 3) therapeutic alliance and investment in treatment. These mechanisms are not altogether surprising, given their association with Linehan’s (1993) treatment model and conceptualization of BPD as a disorder of pervasive dysregulation. Alliance and investment in treatment as mechanisms is consistent with common challenges in treating individuals with BPD, given that treatment dropout rates have been reported as high as 52% (Priebe et al., 2012).

A component analysis of DBT for women with BPD provides further support for skills use as a mechanism. This study compared DBT skills training with crisis management, DBT individual therapy with a non-skills based activities group (to control for treatment dose), and standard DBT treatment (includes individual therapy, group skills training, telephone coaching, and therapist consultation meeting). Linehan et al. (2015) found that while all treatment conditions produced significant improvement in suicidality, self-harm, and use of crisis services, those including skills training resulted in significantly greater improvement in frequency of self-harming behavior and depression. Interestingly, they found that improvements were comparable between the skills training group and the standard DBT treatment package, indicating that skills training is a potent component of the treatment.

2. DBT skills group

Emotion regulation/self-control and skills use have both been cited as mechanisms in BPD treatment outcome and are primary components to the DBT skills group module of DBT. As mentioned above, there is mounting evidence that DBT skills group is a necessary and sufficient component to treatment outcome in DBT. Several studies have examined DBT skills group as a stand-alone treatment targeting symptom reduction for a range of disorders (Valentine, Bankoff, Poulin, Reidler, & Pantalone, 2015). A review of this literature indicates that DBT skills group alone is efficacious at reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety. Several additional studies have examined DBT skills group as an add-on to various individual treatments with positive results (e.g., Fleming, McMahon, Moran, Peterson, & Dreessen, 2015; Klein, Skinner, & Hawley, 2013; Uliaszek et al., 2016). It is important to note that the populations assessed include substantial variation, including BPD (Barnicot, Gonzalez, McCabe, & Priebe, 2016), eating disorders (Klein et al., 2013), and depression (Webb, Beard, Kertz, Hsu, & Björgvinsson, 2016) in both adults and adolescents. Thus understanding the specific mechanisms associated with DBT skills group may be particularly relevant for the future dissemination of this treatment.

The specific skills that are taught in DBT skills group are typically grouped according to module – distress tolerance, emotion regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and mindfulness. Altogether, DBT skills group instructs participants in dozens of skills, while at the same time encouraging the cessation and replacement of dysfunctional coping skills. These two sets of behaviors – functional coping skills and dysfunctional coping skills-are often measured in DBT studies with the DBT Ways of Coping Checklist (WOCCL; Neacsiu, Rizvi, Vitaliano, Lynch, & Linehan, 2010). In this regard, functional coping skills represent those skills taught in DBT skills group, as well as other evidence-based group therapies. These skills, as assessed by the WOCCL, are characterized by adaptive ways to deal with problems or difficult emotions emphasizing both cognitive and behavioral tools. Skills include focusing on positive aspects of a situation, seeking social support, acting assertively, self-soothing, and active problem-solving. The dysfunctional coping skills instead refer to ways a person may address a perceived problematic situation, person, or emotion that can actually worsen problems over time. This includes blaming, avoidance, criticism, and self-medicating. While these behaviors are often seen in those with BPD, they are not specific to a BPD diagnosis and are considered transdiagnostic dysfunctional coping skills.

3. Current study

The present study examines potential mechanisms of action in a randomized control trial comparing DBT skills group to a PPT group intervention for treatment-seeking university students. PPT is a strengths-based treatment approach, where, instead of targeting symptoms explicitly, strengths-based skills are used to encounter symptomology. Previously published results have demonstrated that both interventions resulted in significant reductions in BPD and depressive symptomatology (for details, see Uliaszek et al., 2016). The current study examines change in both functional and dysfunctional coping skills use (reflective of DBT skills), as well as therapeutic alliance, as mechanisms of action in BPD and depressive outcome. Because of the unique study design, we are able to examine the effects of the potential mechanism across the beginning, middle, and end of the treatment protocol.

The hypotheses are as follows:

Increases in functional coping skills use throughout treatment will predict a reduction in BPD and depression symptoms for both groups, as the primary goal of both modalities is to improve skills and strengths among participants.

A reduction in dysfunctional coping skills use early in treatment will predict a reduction in BPD symptoms, specifically for the DBT group. This is specific to the DBT group because the PPT group does not explicitly target dysfunctional coping skills use.

Improved therapeutic alliance will be a mechanism for improved outcome throughout treatment for both groups.

4. Method

A detailed description of the method of this study can be found in Uliaszek et al. (2016).

4.1. Participants

Participants were 54 treatment-seeking university students at a mid-sized university in a large metropolitan area. Participants represented a range of symptoms of psychopathology deemed relevant for group therapy targeting “severe emotion dysregulation.” Exclusion criteria included severe cognitive disturbance or psychotic disorder. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the sample. The groups did not differ on any demographic or diagnostic variables at baseline.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 54 randomized participants.

| Total n =54 | DBT n = 27 | PPT n = 27 | Test statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dropout, n (%) | 16 (30%) | 4 (15%) | 12 (44%) | χ2 (1) = 5.68* |

| Number of group sessions attended, mean (SD) | 7.17 (3.43) | 9.04 (2.55) | 5.31 (3.21) | t (50) = 4.64*** |

| Age, range; mean (SD) | 18–46 22.17 (5.01) |

22.07 (4.81) | 22.26 (5.28) | t (52) = − .14 |

| Female, n (%) | 42 (78%) | 21 (78%) | 21 (78%) | χ2 (1) = 0 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | χ2 (5) = 4.92 | |||

| African-American | 5 (9%) | 3 (11%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Asian-American | 20 (37%) | 7 (26%) | 13 (50%) | |

| Biracial/Multiracial | 2 (4%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Caucasian | 15 (28%) | 9 (33%) | 6 (23%) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (6%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | |

| Other | 8 (15%) | 4 (15%) | 4 (15%) | |

| Previous hospitalization, n (%) | 7 (13%) | 5 (19%) | 2 (7%) | χ2 (1) = 1.35 |

| Current medication, n (%) | 21 (40%) | 12 (44%) | 9 (33%) | χ2 (1) = 4.82 |

| Individual psychotherapy, n (%) | 37 (70%) | 22 (81%) | 15 (56%) | χ2 (1) = 3.56 |

| Year in University, n (%) | χ2 (5) = 4.82 | |||

| 1st year | 6 (11%) | 3 (11%) | 3 (11%) | |

| 2nd year | 14 (26%) | 6 (22%) | 8 (30%) | |

| 3rd year | 15 (28%) | 8 (30%) | 7 (27%) | |

| 4th year | 11 (20%) | 4 (15%) | 7 (27%) | |

| 5th year | 6 (11%) | 5 (19%) | 1 (17%) | |

| Graduate school | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| DSM-IV Axis I Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| MDD | 22 (43%) | 13 (48%) | 10 (37%) | χ2 (1) = .68 |

| Dysthymic Disorder | 15 (28%) | 6 (22%) | 9 (33%) | χ2 (1) = .83 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 3 (6%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | χ2 (1) = .35 |

| Substance Use Disorder | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | χ2 (1) = 1.02 |

| Panic Disorder | 11 (20%) | 6 (22%) | 5 (19%) | χ2 (1) = .11 |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 18 (33%) | 9 (33%) | 9 (33%) | χ2 (1) = 0 |

| OCD | 9 (17%) | 6 (22%) | 3 (11%) | χ2 (1) = 1.20 |

| PTSD | 6 (11%) | 3 (11%) | 3 (11%) | χ2 (1) = 0 |

| GAD | 12 (22%) | 5 (19%) | 7 (26%) | χ2 (1) = .43 |

| DSM-IV Axis II Diagnosis, | n (%) | |||

| AVPD | 16 (30%) | 9 (33%) | 7 (26%) | χ2 (1) = .36 |

| OCPD | 22 (41%) | 13 (48%) | 9 (33%) | χ2 (1) = 1.23 |

| SPD | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| NPD | 2 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | χ2 (1) = 0 |

| BPD | 17 (31%) | 9 (33%) | 8 (30%) | χ2 (1) = .09 |

| APD | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Number of Diagnoses, mean (SD) | 2.87 (1.99) | 3.04 (1.91) | 2.70 (2.09) | t (52) = .61 |

| Life Problems Inventory | 154.85 (35.21) | 158.22 (37.84) | 151.35 (32.61) | t (51) = .71 |

| Symptom Checklist-90 Revised | 2.22 (.93) | 2.38 (.89) | 2.05 (.96) | t (51) = 1.33 |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .001;

DBT = dialectical behavior therapy group; PPT = positive psychotherapy group; MDD = major depressive disorder; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; AVPD = avoidant personality disorder; OCPD = obsessive-compulsive personality disorder; SPD = schizotypal personality disorder; NPD = narcissistic personality disorder; BPD = borderline personality disorder; APD = antisocial personality disorder.

4.2. Procedures

Identification numbers were assigned to all eligible participants; these numbers were randomly selected and separated into two groups (A and B). Groups A and B were then randomly assigned to be either DBT or PPT. Both groups ran at the same time and day on campus to avoid day or time effects. This also eliminated the option of participants self-selecting into a particular group based on scheduling. The group schedule was 12 weeks, 2 h per week. The DBT group included skills from all four of the standard skills training modules (Linehan, 2015), but was modified for a 12-week curriculum. This included three weeks each of distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and emotion regulation skills with a single mindfulness-focused group preceding each new module. The PPT group included weekly handouts, activities, and homework assignments focusing on increasing pleasure, engagement, and meaning-making in life (Seligman, Rashid, & Parks, 2006).

The pretreatment assessment included informed consent procedure, two self-report questionnaires, and a full diagnostic interview. Participants completed an additional battery of questionnaires through an online survey system. Mid-treatment assessments were completed in the final 15 min of group sessions on weeks three, six, and nine. Participants absent from group did not complete these measures. Assessments were administered by a research assistant and the group leader left the room to avoid influencing ratings of therapeutic alliance. Post-treatment assessments were generally completed within two weeks of the ending of group and were identical to the pretreatment assessments, with the addition of the therapeutic alliance questionnaire.

Because participants needed to be present at group to complete midtreatment measures, missingness related to midtreatment measures is associated with attrition, and thus associated with treatment group. Rates of completion of putative mechanism measures is as follows: week 3 (n = 35), week 6 (n = 30), and week 9 (n = 28). While we did contact all participants regardless of dropout to complete posttreatment measures, only thirty-five participants supplied data. All analyses were conducted on this modified intent-to-treat (ITT) sample (i.e., the sample included all patients who had an assessment at the respective time point evaluated, regardless of the number of treatment sessions attended). Sample sizes varied per analysis on the basis of variations in missing data across the different assessment measures.

4.3. Measures

4.3.1. Diagnostic interview

BPD symptom count included in the present analyses were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1996). This semi-structured interview was administered by research assistants after undergoing significant didactic and reliability training. The first author (a registered clinical psychologist) attended 15% of diagnostic interviews and rated them separately. Kappa coefficients were computed based on these ratings was 1.0 for BPD.

4.3.2. Self-report measures

The Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL; Derogatis, 1983) is a 90-item self-report scale measuring general psychiatric symptom distress. Reliability of the depression subscale (SCL-depression) was 0.85. The Life Problems Inventory (LPI; Wagner, Rathus, & Miller, 2015) is a 60-item scale assessing symptoms associated with BPD. This measure was reliable in the present study (α = 0.94). The pretreatment LPI total score in the current sample was approximately two standard deviations above a normed LPI total score in an undergraduate sample (Wagner et al., 2015). The WOCCL is a 59-item self-report scale assessing frequency of adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies. The measure includes two subscales assessing functional (α = 0.90) and dysfunctional (α = 0.84) coping skills use. Examples of functional coping skill items include: Counted my blessings and Just took things one step at a time. Examples of dysfunctional coping skill items include: Blamed others and Avoided people. Therapeutic alliance was measured using the client version of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Horvath & Greenberg, 1989). The WAI is a 36-item self-report measure that assesses perceived alliance related to goals, tasks, and bonds. The reliability of the WAI at week 3 was 0.73. A description of change in these measures over the course of treatment can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1.

4.3.3. Data analysis plan

All analyses were completed using Mplus Version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). ITT analyses assume that data are missing at random (MAR). In other words, there may be missing data, but missingness should be due to observed, rather than unobserved, variables (see Graham, 2009 for review). Because missingness was due almost exclusively to dropout/attendance (specifically related to participation in the PPT group)- variables that are observed and analyzed-this satisfied the parameters of MAR. However, because of variability in missingness across timepoints, we did assess for systematic bias as a result of dropout/missingness by examining patterns of missingness as a moderator in key analyses (e.g., Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997). This was done by assigning each participant to a group based on their pattern of missing data at weeks 3, 6, 9, and posttreatment. The interaction between this variable and the key mechanism variables in predicting outcomes of interest was then examined. No significant main effects of pattern or interactions with pattern were significant, increasing our confidence that missingness did not bias the following results. As a further safeguard, we used robust maximum likelihood estimation in our path models, an estimation technique robust to nonnormal and irregular data.

In a systematic review of mechanism studies in BPD, Rudge et al. (2017, pg. 2) highlight two criteria for differentiating mechanism studies from outcome studies: (1) Is the studied variable theorised to be a mechanism of change in a (separately defined) outcome variable? (2) Does the data presented investigate an association/correlation between the proposed mechanistic variable and an outcome variable? We extend this broad definition by proposing that a mechanism must predict the outcome after accounting for differential pretreatment levels of both the mechanism and the outcome variable. To this end, the relationship between the potential mechanism and the outcome represents change in the mechanism predicting change in the outcome variable. While this may depart from more traditional mediation analyses (e.g., Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002)), too often studies are not equipped to study the mechanism at multiple timepoints throughout treatment while accounting for change and baseline levels of all included variables.

To examine mechanistic paths in the way described above, path models were estimated examining the relationships between post-treatment mechanism and outcome, including autoregressive paths with mechanism at baseline (pretreatment for WOCCL and week 3 for WAI) predicting the mechanism of interest and outcome at pretreatment predicting outcome at posttreatment. Because we were additionally interested in the differential effects of the mechanism across group, an interaction term was created between group and the mechanism. This term, along with the main effect of group, was also entered into the equation to examine moderation. This resulted in nine separate models exploring three mechanisms variables (functional and dysfunctional subscales of the WOCCL and the WAI) with three outcomes (BPD, LPI, and SCL-depression).

After these path analyses were completed, we paid specific attention to those models accounting for a significant amount of variance in the outcome variable through the observed R2 for each model1. Exploratory analyses were then conducted for the variables in those models. More specifically, we then submitted the specific mechanism and outcome relationship to longitudinal analyses exploring the effect of the mechanism after week 3, week 6, and week 9 in separate analyses (only weeks 6 and 9 for WAI analyses). This would allow a determination of whether change in mechanism was most predictive of outcome early, mid, or late in treatment.

Finally, significant interaction effects were further explored by examining the above models separately across group. In these analyses, the model included the mechanism of interest predicting posttreatment outcome, controlling for pretreatment mechanism and outcome. Comparisons between groups were then examined in terms of strength and direction of association between mechanism and outcome.

5. Results

5.1. Posttreatment mechanism as a predictor of outcome

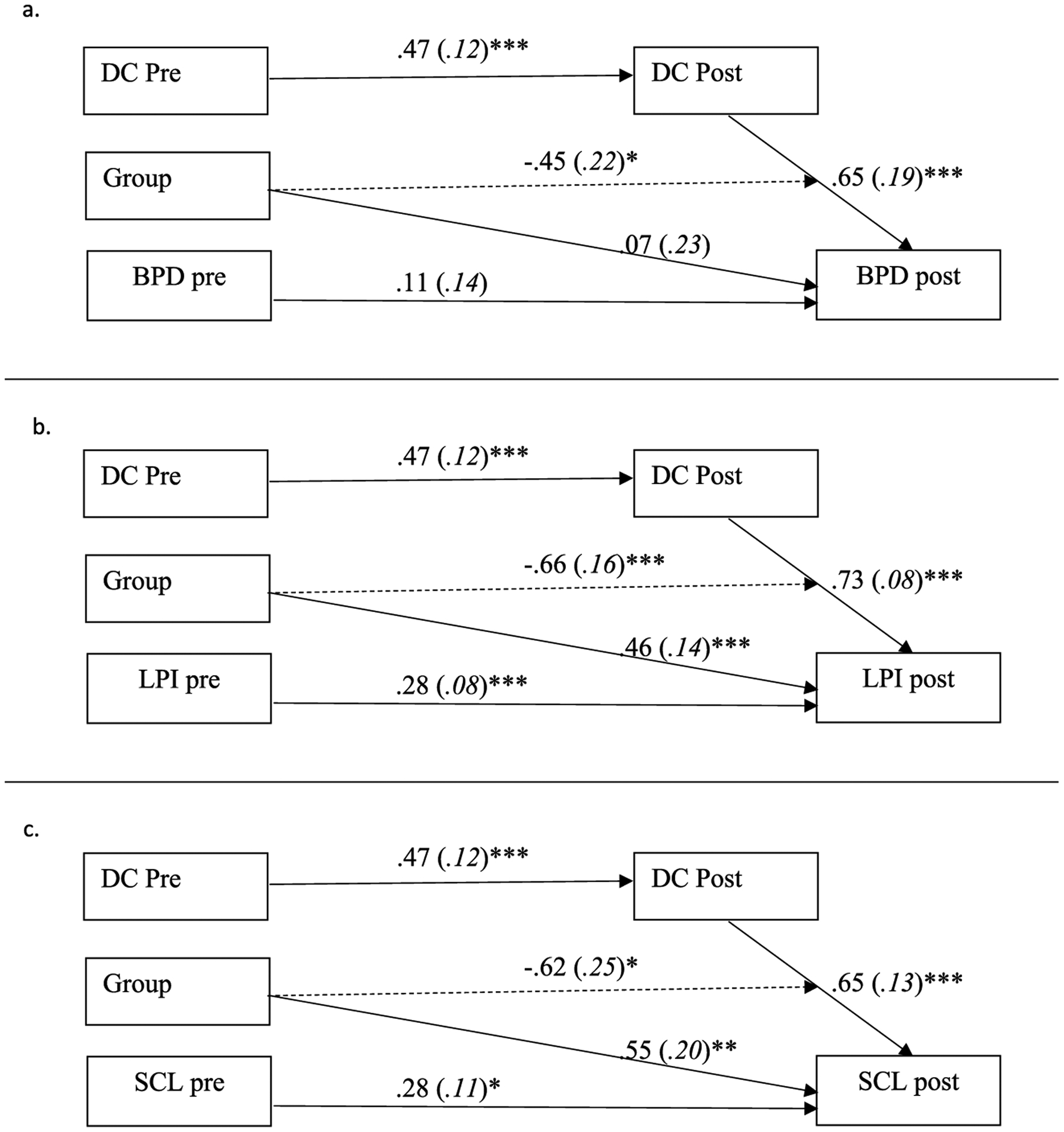

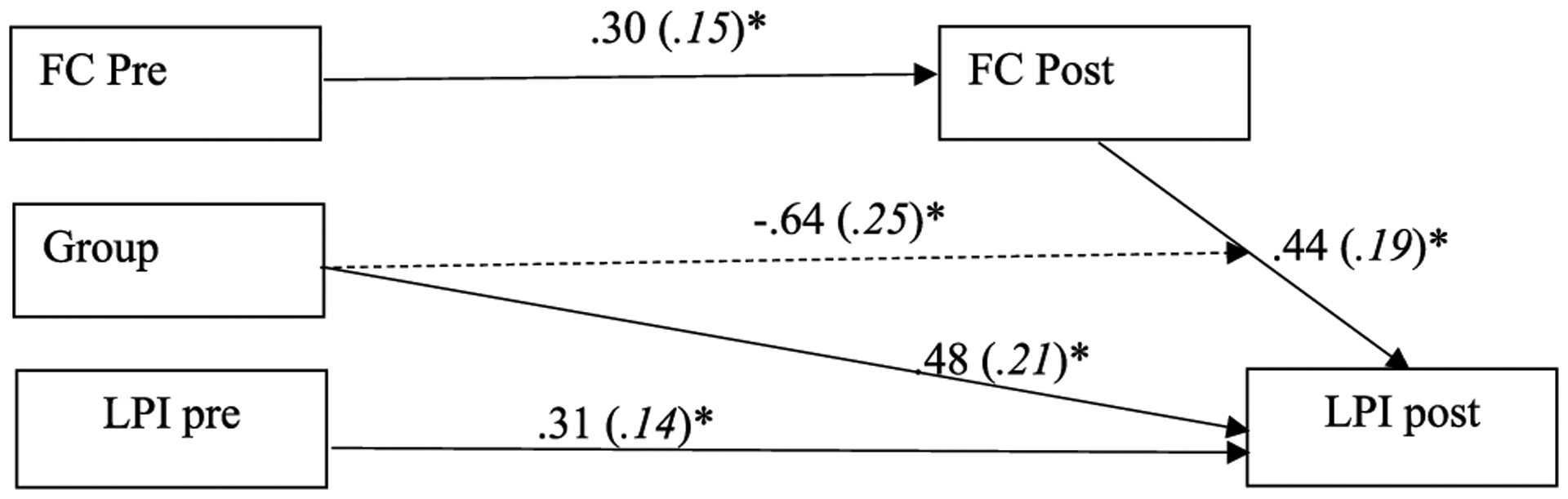

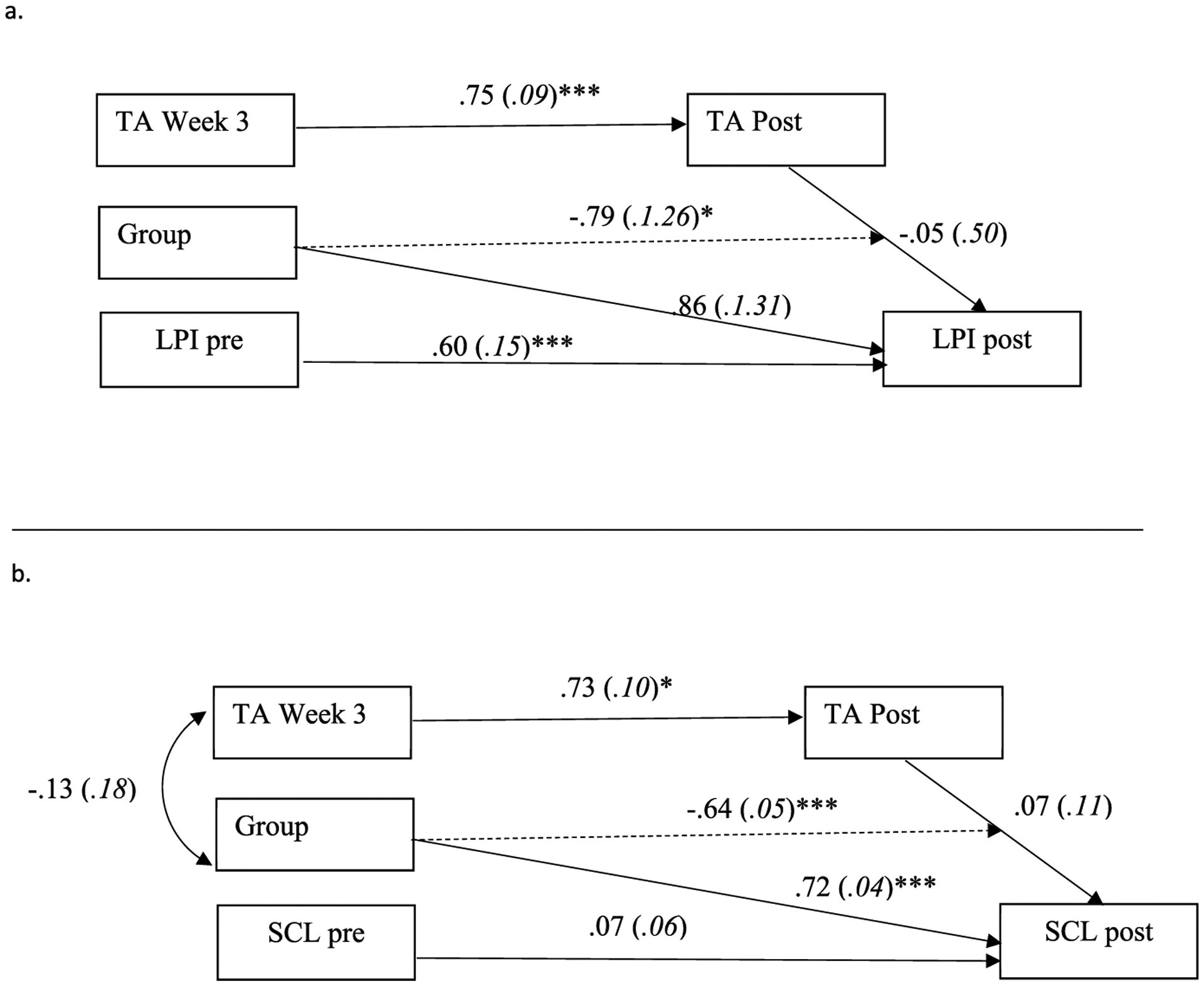

The three putative mechanisms at posttreatment were examined as predictors of the three posttreatment outcomes in nine separate analyses. Total variance accounted for in the outcomes are presented in Table 2. Six models demonstrated significant variance accounted for in the outcome: dysfunctional coping skills predicting BPD symptoms, LPI, and SCL-depression (Fig. 1); functional coping skills predicting LPI (Fig. 2); therapeutic alliance predicting LPI and SCL-depression (Fig. 3). The interaction between group and outcome was a significant predictor of outcome in all models, thus main effects were not interpreted. The remaining three models can be found in Supplementary Figs. 2–3. It should be noted that a correlated error was found between group and therapeutic alliance at week three in the model predicting SCL-depression so this was corrected in the model and subsequent models exploring these relationships.

Table 2.

Total Variance Accounted for in the Outcome Variables (Posttreatment Borderline Personality Disorder and Depression Symptoms) by the Mechanism (Dysfunctional Coping, Functional Coping, Therapeutic Alliance) and Group, as Well as the Interaction between Mechanism and Group. Baseline Mechanism and Outcome are also Accounted for in Each Model.

| Posttreatment | Week 3 | Week 6 | Week 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 (standard error) | R2 (standard error) | R2 (standard error) | R2 (standard error) | |

| Dysfunctional Coping | ||||

| SCID-II-BPD | .47 (.24)* | .46 (.31) | .61 (.22)** | .31 (.23) |

| LPI | .83 (.08)*** | .35 (.19) | .29 (.17) | .39 (.15)** |

| SCL-Depression | .68 (.19)*** | .23 (.20) | .37 (.20) | .67 (.38) |

| Functional Coping | ||||

| SCID-II-BPD | .15 (.11) | |||

| LPI | .53 (.25)* | .29 (.15) | .87 (.14)*** | .33 (.35) |

| SCL-Depression | .45 (.30) | |||

| Therapeutic Alliance | ||||

| SCID-II-BPD | .22 (.42) | |||

| LPI | .46 (.14)*** | .18 (.14) | .98 (.02)*** | |

| SCL-Depression | .94 (.06)*** | .89 (.12)*** | .93 (.11)*** | |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

SCID-II-BPD = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II borderline personality disorder symptom count; LPI = Life Problems Inventory; SCL-Depression = Symptom Checklist 90 Revised Depression subscale.

Fig. 1.

Path Models Demonstrating a Relationship between Posttreatment Dysfunctional Coping Skills (DC Post) and Borderline Personality Disorder Symptom (BPD; panel a), Life Problems Inventory (LPI; panel b), and Symptom Checklist-Depression (SCL; panel c) Outcomes when Accounting for Baseline DC and Outcome. Dashed Lines Indicate Moderation Path. Group (DBT = 1; PPT = 2). Paths Represent Standardized Regression Weights with Standard Errors in Parentheses. Note. * = p < .05; ** = p < .01; *** = p < .001.

Fig. 2.

Path Model Demonstrating a Relationship between Posttreatment Functional Coping Skills (FC Post) and Life Problems Inventory (LPI) Outcomes when Accounting for Baseline FC and LPI. Dashed Line Indicates Moderation Path. Group (DBT = 1; PPT = 2). Paths Represent Standardized Regression Weights with Standard Errors in Parentheses. Note. * = p < .05.

Fig. 3.

Path Models Demonstrating a Relationship between Posttreatment Therapeutic Alliance (TA Post) and Life Problems Inventory (LPI; panel a) and Symptom Checklist- Depression (SCL; panel b) Outcomes when Accounting for Baseline TA and Outcome. Dashed Lines Indicate Moderation Paths. Group (DBT = 1; PPT = 2). Paths Represent Standardized Regression Weights with Standard Errors in Parentheses. Note. * = p < .05; *** = p < .001.

5.2. Exploratory analyses examining mechanism as a predictor across time

The six significant models described above were then explored across time to more specifically pinpoint when during the course of treatment the effect of the mechanism was most pronounced. These models were identical to the ones above, except that the mechanism at posttreatment was replaced with the mechanism at week 3, week 6, and week 9 in three separate models (only week 6 and 9 therapeutic alliance as week 3 was the baseline). This resulted in an additional 16 models examined. Total variance accounted for in these outcomes are presented in Table 2. Standardized regression weights of the predictors of interest (mechanism, group, and the interaction of mechanism and group) are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Standardized regression weights (standard errors) of the mechanism (dysfunctional coping, functional coping, therapeutic alliance) and group, as well as the interaction between mechanism and group predicting the outcome variables (posttreatment borderline personality disorder and depression symptoms) examined in the exploratory analyses.

| Mechanism | Predictors | Week 3 | Week 6 | Week 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysfunctional Coping Skills | SCID-II-BPD | |||

| Dysfunctional Coping | .44 (.28) | .62 (.18)*** | −.04 (.44) | |

| Group | −.03 (.41) | .11 (.20) | −.79 (.34)* | |

| DC*Group | −.27 (.49) | −.37 (.28) | .84 (.57) | |

| LPI | ||||

| Dysfunctional Coping | .30 (.44) | .45 (.32) | .21 (.82) | |

| Group | −.02 (.59) | −.23 (.35) | −.59 (1.09) | |

| DC*Group | −.04 (.78) | .29 (.35) | .81 (1.59) | |

| SCL-Depression | ||||

| Dysfunctional Coping | .25 (.53) | .39 (.43) | −.14 (.22) | |

| Group | .21 (.58) | .10 (.49) | −.52 (.07)*** | |

| DC*Group | −.06 (.87) | .07 (.82) | .80 (.07)*** | |

| Functional Coping Skills | LPI | |||

| Functional Coping | .21 (.39) | −.21 (.08)* | −.26 (.35) | |

| Group | .35 (.54) | −.56 (.10)*** | −.67 (.72) | |

| FC*Group | −.39 (.68) | .69 (.06)*** | .86 (.78) | |

| Therapeutic Alliance | LPI | |||

| Therapeutic Alliance | .07 (.51) | .07 (.07) | ||

| Group | .47 (1.35) | .69 (.06)*** | ||

| TA*Group | −.41 (1.40) | −.66 (.07)*** | ||

| SCL-Depression | ||||

| Therapeutic Alliance | .16 (.11) | .05 (.10) | ||

| Group | .68 (.07)*** | .70 (.06)*** | ||

| TA*Group | −.57 (.10)*** | −.63 (.10)*** |

Note.

p <.05;

p < .001;

SCID-II-BPD = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II borderline personality disorder symptom count; LPI = Life Problems Inventory; SCL-Depression = Symptom Checklist 90 Revised Depression subscale; DC = Dysfunctional coping skills; FC = Functional coping skills; TA = Therapeutic alliance. Group (DBT = 1; PPT = 2).

5.2.1. Dysfunctional coping skills

For dysfunctional coping skills predicting BPD symptoms, only week 6 explained a significant amount of variance in the outcome. In that case, high dysfunctional coping at week 6 predicted worse BPD symptoms. When predicting LPI, only week 9 mechanism explained a significant amount of variance and this was driven by a significant effect of group. For SCL-depression, none of the mechanisms across the weeks predicted a significant amount of variance in the outcome. However, week 9 evidenced the largest effect and both group and the interaction between group and dysfunctional coping was a significant predictor.

5.2.2. Functional coping skills

In predicting the LPI across the course of treatment, only functional coping skills only at week 6 was a significant predictor. Functional coping skills, group, and their interaction were all significant predictors.

5.2.3. Therapeutic alliance

For therapeutic alliance predicting LPI, only week 9 therapeutic alliance explained a significant amount of variance in the outcome. Both group and the interaction between group and therapeutic alliance were significant predictors of LPI at posttreatment. Both week 6 and week 9 models predicted a significant amount of variance in the SCL-depression at posttreatment. In both of these weeks, group and the interaction between group and therapeutic alliance predicted post-treatment SCL-depression.

5.3. Exploration of group differences for significant interactions

In the planned analyses analyzing the effect of posttreatment mechanism on outcome, six relationships had a significant moderation effect (Fig. 1). After examining these relationship across timepoints, five additional significant interactions were found (Table 3). Because main effects are uninterpretable in the presence of a significant interaction, we then examined the standardized regression weights of the mechanism of interest predicting outcome, controlling for baseline mechanism and outcome, separately for the DBT and PPT groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Standardized regression weights (standard errors) of the mechanism (dysfunctional coping, functional coping, therapeutic alliance) predicting the outcome variables (posttreatment borderline personality disorder and depression symptoms) analyzed separately by group for analyses with a significant interaction.

| Posttreatment | Week 6 | Week 9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBT | PPT | DBT | PPT | DBT | PPT | |

| Dysfunctional Coping | ||||||

| SCID-II-BPD | .44 (.16)** | .19 (.20) | ||||

| LPI | .60 (.10)*** | −.06 (.20) | ||||

| SCL-Depression | .46 (.15)** | −.11 (.21) | .58 (.10)*** | .64 (.22)** | ||

| Functional Coping | ||||||

| LPI | .16 (.16) | −.29 (.22) | .15 (.13) | .75 (.18)*** | ||

| Therapeutic Alliance | ||||||

| LPI | −.30 (.20) | −.42 (.21)* | −.07 (.16) | −.59 (.24)* | ||

| SCL-Depression | −.20 (.20) | −.84 (.09)*** | .09 (.19) | −.45 (.21)* | −.05 (.19) | −.83 (.12)*** |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

DBT = dialectical behavior therapy group; PPT = positive psychotherapy group; SCID-II-BPD = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II borderline personality disorder symptom count; LPI = Life Problems Inventory; SCL-Depression = Symptom Checklist 90 Revised Depression subscale.

5.3.1. Dysfunctional coping skills

When examining the effect of posttreatment dysfunctional coping skills on all three significant outcomes (BPD symptoms, LPI, and SCL-depression), it was clear that this effect was only found in the DBT group and not in the PPT group, with higher dysfunctional coping predicting higher symptom outcome. This effect was not seen at any of the interim timepoints.

5.3.2. Functional coping skills

For posttreatment functional coping skills predicting LPI, it appears that the DBT group and PPT group were having differing effects, although neither effect approached significance. However, at week 6, the PPT group showed a significance effect of high functional coping skills predicting higher LPI, contrary to hypotheses.

5.3.3. Therapeutic alliance

When examining the effect of posttreatment therapeutic alliance on both LPI and SCL-depression, results supported a clear effect for only the PPT group, with higher therapeutic alliance predicting better outcome. This effect was not seen at any of the interim timepoints. This was consistent at week 6 for SCL-depression and at week 9 for both outcomes.

6. Discussion

The present study examined three putative mechanisms predicting both BPD and depressive outcomes in randomized group therapy interventions targeting treatment-seeking university students. Overall, results suggested that change in dysfunctional coping behaviors is primarily a mechanism of change for DBT and not PPT in both BPD and depression outcomes, and that this was true specifically in mid-to late-treatment. The opposite was true for therapeutic alliance, with this emerging as a mechanism primarily for PPT and not DBT, with this effect consistent throughout the course of treatment. Only limited evidence emerged for functional coping skills as a mechanism in PPT. This study provides preliminary evidence suggesting differential mechanisms of change across group therapies for university students.

We first examined the omnibus effect of the putative mechanisms by examining their predictive power in path models predicting outcomes of interest that also included the exploration of a moderating effect of group membership (while accounting for baseline mechanism and outcome). If the model explained a significant amount of variance in the outcome, we then conducted exploratory analyses looking at the effect of the mechanism across the course of therapy and explored any interaction effects in further detail.

The dysfunctional coping subscale of the WOCCL describes a variety of maladaptive coping techniques. We predicted that effects for this mechanism would be more present in DBT because many of these behaviors are directly targeted by the intervention. This hypothesis was supported with dysfunctional coping skills use significantly predicting both BPD and depressive outcomes overall, as well as in week 6 and in week 9. For PPT, the significant main effect of dysfunctional coping skills at week 6 (without the presence of an interaction effect) and a significant effect for PPT at week 9 suggests that the role of dysfunctional coping skills may be explored further in PPT but it is unlikely to be a primary mechanism. The findings of this study support the supposition that DBT works primarily through stopping several unhelpful cognitive and behavioral strategies as a way of reducing psychopathology symptoms. The fact that we did not find support for this effect at week 3 suggests that true change in dysfunctional coping happens more during mid- and late-treatment.

Functional coping skills use, as assessed by the WOCCL, is characterized by adaptive ways to deal with problems or difficult emotions. While DBT and PPT are distinct, both treatments do emphasize many of these skills within their respective theoretical frameworks. Thus, it was surprising that improvement in functional coping was not found to be a consistent mechanism of change for either group. Perhaps skill building is important in DBT for improved quality of life or other outcomes related to relationships or occupational/educational functioning, but has less of an effect compared to more potent mechanisms, such as the reduction of dysfunctional coping behaviors. For PPT, a therapy that focuses on improving positive coping, functional coping skills use at midtreatment was predictive of worse self-reported BPD outcomes. It is possible that even though behavior was changing at this time, growing pains associated with new functional behaviors resulted in exacerbated emotional or interpersonal suffering at posttreatment. Alternatively, participants reporting high use of skills may have been experiencing more problems necessitating the use of skills. If they were using a high amount of skills, but not finding them helpful, this could be an explanation of worse outcome. Of course, this result needs to be replicated.

Finally, positive therapeutic alliance – including bond with the group leader, agreement on the goals of treatment, and the tasks assigned – is likely a common mechanism among most treatments. However, this was not supported in the present study. Instead, therapeutic alliance appeared to be a mechanism of change only for the PPT group and this finding was consistent throughout the course of treatment, even in the latter half of the group. This was found for both self-reported BPD and depression symptoms. For PPT, continued engagement regarding the goals and tasks in treatment, as well and forging close interpersonal relationships, made a significant impact of outcome. This was not supported in the DBT group, although this group had significantly higher overall therapeutic alliance ratings compared to the PPT group (Uliaszek et al., 2016). While this may be a result of enjoyment and bonding within the DBT group, we did not find evidence that it was predictive of outcome.

While this study presents exciting findings regarding the mechanisms of action in both DBT and PPT in outcomes for treatment-seeking university students, there are several limitations to note. First, the small sample size and variations in missing data may have resulted in the instability of some of the findings. Because mid-treatment assessments were given during group, those participants with poor attendance or who dropped out of treatment (4 in the DBT group and 12 in the PPT group) did not supply data. For this reason, it is likely that the results for PPT are best represented as results for treatment responders, particularly results relevant to the later treatment sessions when dropout was highest. Second, we were unable to provide adherence ratings for either group due to a technical failure. Thus, we cannot definitively state that our groups were adherent to the DBT or PPT models. Third, although we emphasize BPD outcomes, only 31% of the sample met full diagnostic criteria for BPD. However, 93% of the sample reported at least one clinically significant symptom of BPD and mean LPI scores were significantly above undergrad norms, so we believe these results are applicable to those with BPD. Finally, it is important to note that 70% of the participants were also receiving individual therapy when enrolled in the study – common standard of care in a college counseling center when the participants are high in suicidality and BPD symptoms. Thus, our results cannot state definitively whether these findings would be applicable to group therapy as a stand-alone treatment.

This study has several strengths that provide insight into the mechanisms of action into two brief group therapies for treatment-seeking university students. First, we examined putative mechanisms that were thought to be both specific to DBT (e.g., dysfunctional coping skills) and PPT (e.g., functional coping skills) and common across treatments (e.g., therapeutic alliance) with findings generally providing proof of theory that DBT reduces symptoms by reduces dysfunctional coping skills use and PPT reduces symptoms through therapeutic alliance. Second, we were able to draw specific evidence for certain mechanisms being more potent at particular times during a brief treatment protocol. For example, we found no significant effects for mechanisms at week three suggesting that true impactful change in mechanism does not occur until mid-to late-treatment. Taken together, these results represent an exciting step forward to the further refinement and elucidation of effective treatments for treatment-seeking university students.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.07.006.

1 We decided to use R2 as opposed to overall model fit because we were interested primarily in only two paths of the model, not the overall fit of the path model and the other predictors in the model. Also, model fit was compromised due to the small sample size and would not have been an appropriate metric to incorporate. Model fit statistics are available upon request from the first author.

References

- Barnicot K, Gonzalez R, McCabe R, & Priebe S (2016). Skills use and common treatment processes in dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 52, 147–156. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR (1983). SCL 90-R: Administration, scoring, and procedure manual. Towson, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research. [Google Scholar]

- First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer R, Williams J, & Benjamin L (1996). User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AP, McMahon RJ, Moran LR, Peterson AP, & Dreessen A (2015). Pilot randomized controlled trial of dialectical behavior therapy group skills training for ADHD among college students. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19(3), 260–271. 10.1177/1087054714535951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS, Korslund KE, & Linehan MM (2014). A pilot randomized controlled trial of dialectical behavior therapy with and without the dialectical behavior therapy prolonged exposure protocol for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 55, 7–17. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, & Gibbons RD (1997). Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 2, 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, & Greenberg LS (1989). Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(2), 223–233. 10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AS, Skinner JB, & Hawley KM (2013). Targeting binge eating through components of dialectical behavior therapy: Preliminary outcomes for individually supported diary card self-monitoring versus group-based DBT. Psychotherapy, 50(4), 543–552. 10.1037/a0033130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koons CR, Robins CJ, Tweed JL, Lynch TR, Gonzalez AM, Morse JQ, … Bastian LA. (2001). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy, 32(2), 371–390. 10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80009-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson T, Fairburn CG, & Agras WS (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M (2015). DBT skills training manual (2nd ed). New York, NY: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, … Lindenboim N (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(7), 757–766. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD, … Murray-Gregory AM (2015). Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: A randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(5), 475–482. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TR, Morse JQ, Mendelson T, & Robins CJ (2003). Dialectical behavior therapy for depressed older adults: A randomized pilot study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(1), 33–45. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12527538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Rathus JH, & Linehan M (2006). Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed). Los Angeles: CA: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Neacsiu AD, Rizvi SL, Vitaliano PP, Lynch TR, & Linehan MM (2010). The dialectical behavior therapy ways of coping checklist: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(6), 563–582. 10.1002/jclp.20685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistorello J, Fruzzetti AE, MacLane C, Gallop R, & Iverson KM (2012). Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) applied to college students: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 982–994. 10.1037/a0029096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S, Bhatti N, Barnicot K, Bremner S, Gaglia A, Katsakou C, … Zinkler M (2012). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy for self-harming patients with personality disorder: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 81(6), 356–365. 10.1159/000338897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudge S, Feigenbaum J, & Fonagy P (2017). Mechanisms of change in dialectical behaviour therapy and cognitive behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health, 1–11. 10.1080/09638237.2017.1322185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Rashid T, & Parks AC (2006). Positive psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 61(8), 774–788. 10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uliaszek AA, Rashid T, Williams GE, & Gulamani T (2016). Group therapy for university students: A randomized control trial of dialectical behavior therapy and positive psychotherapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 78–85. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine SE, Bankoff SM, Poulin RM, Reidler EB, & Pantalone DW (2015). The use of dialectical behavior therapy skills training as stand-alone treatment: A systematic review of the treatment outcome literature. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 1–20. 10.1002/jclp.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D, Rathus JH, & Miller AL (2015). Psychometric evaluation of the life problems inventory, a measure of borderline personality features in adolescents. Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy, 5(4), 1–9. 10.4172/2161-0487.1000198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webb CA, Beard C, Kertz SJ, Hsu KJ, & Björgvinsson T (2016). Differential role of CBT skills, DBT skills and psychological flexibility in predicting depressive versus anxiety symptom improvement. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 81, 12–20. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.