Abstract

Objective

To investigate psychological and behavioural responses to COVID-19 among the Chinese general population.

Design, setting and participants

We conducted a population-based mobile phone survey between 1 February and 10 February 2020 via random digit dialling. A total of 1011 adult residents in Wuhan (n=510), the epicentre and quarantined city, and Shanghai (n=501) were interviewed. Proportional quota sampling and poststratification weighting were used. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to investigate perception factors associated with the public responses.

Primary outcome measures

We measured anxiety levels using the 7-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) and asked respondents to report their precautionary behaviours before and during the outbreak.

Results

The prevalence of moderate or severe anxiety was significantly higher (p<0.001) in Wuhan (32.8%) than Shanghai (20.5%). Around 79.6%–88.2% residents reported always wearing a face mask when they went out and washing hands immediately when they returned home, with no discernible difference across cities. Only 35.5%–37.0% of residents reported a handwashing duration above 40 s as recommended by the WHO. The strongest predictor of moderate or severe anxiety was perceived harm of the disease (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.1), followed by confusion about information reliability (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.5 to 1.9). None of the examined perception factors were associated with odds of handwashing duration above 40 s.

Conclusions

Prevalence of moderate or severe anxiety and strict personal precautionary behaviours was generally high, regardless of the quarantine status. Our results support efforts for handwashing education programmes with a focus on hygiene procedures in China and timely dissemination of reliable information.

Keywords: public health, mental health, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Demographically representative samples of residents in Wuhan (the epicentre of the COVID-19 outbreak in China) and Shanghai were obtained via random digit dialling with quota sampling during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in China.

A wide range of outcomes were collected, including precautionary behaviours before and during the outbreak, and anxiety levels and unwarranted behaviours during the outbreak.

Perception variables, personal characteristics, and level of information exposures associated with the psychological and behavioural outcomes were examined using multivariable logistic regression models with poststratification weighting.

Although the response rate was not low compared with a telephone survey, participants were informed of the survey topic before consent had been obtained, which may compromise the findings due to non-response bias on the basis of interest in the topic.

Introduction

In December 2019, COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 emerged in Wuhan city, China.1 As of 19 April 2020, a total of 82 735 COVID-19 cases with 4632 deaths had been reported in mainland China.2 The outbreak has now spread to 213 countries, areas or territories.3 On 31 January 2020 (Beijing time), the WHO declared the coronavirus outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. During 23 January to 8 April 2020, the Chinese government shut down departure channels from Wuhan and nearby cities, hoping to stop the disease from spreading to other parts of the country. However, millions of people had left Wuhan before the lockdown because of the approaching Spring Festival holiday.

Containment measures in the COVID-19 outbreak have focused on identifying, treating and isolating infected people, tracing and quarantining their close contacts, and promoting precautionary behaviours among the general public. Therefore, the psychological and behavioural responses of the general population would play an important role in the control of the outbreak. Previous studies have explored on this topic in various culture settings with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS),4–6 pandemic influenza A(H1N1)7–10 and influenza A(H7N9).11–13 Cultural differences, government involvement, disease perceptions and the stage of the outbreak are associated with public responses, and these factors vary by diseases and settings.4 5 8 14–16

Recent studies have focused on mental health status among healthcare workers and patients during the COVID-19 outbreak.17–19 However, little is known about precautionary and psychological responses among the Chinese general population, which may be different from usual days or responses to previous disease outbreaks owing to two main reasons. First, the entire public was faced with highly inconsistent information, partly because knowledge of the newly emerging disease is evolving with the course of the outbreak. Second, government engagement at all levels has been strong, for instance, running intense public message campaigns about social distancing and personal prevention practices, adopting strict closed-off community management (including setting up temperature checking points and issuing entry permits), and extending holidays and school closures.

In addition, identifying factors of precautionary behaviour and anxiety that can be intervened by policy is helpful for containing outbreaks and preventing public overreaction. Previous studies have shown that the two outcomes are associated with perceived efficacy of recommended behaviours and risk perception of diseases.5 7 11 In this study, we aimed to investigate anxiety levels and changes in precautionary behaviours among the general population during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. We also compared public responses across cities with different disease exposures and examined their associations with public perceptions.

Methods

Cross-sectional telephone survey

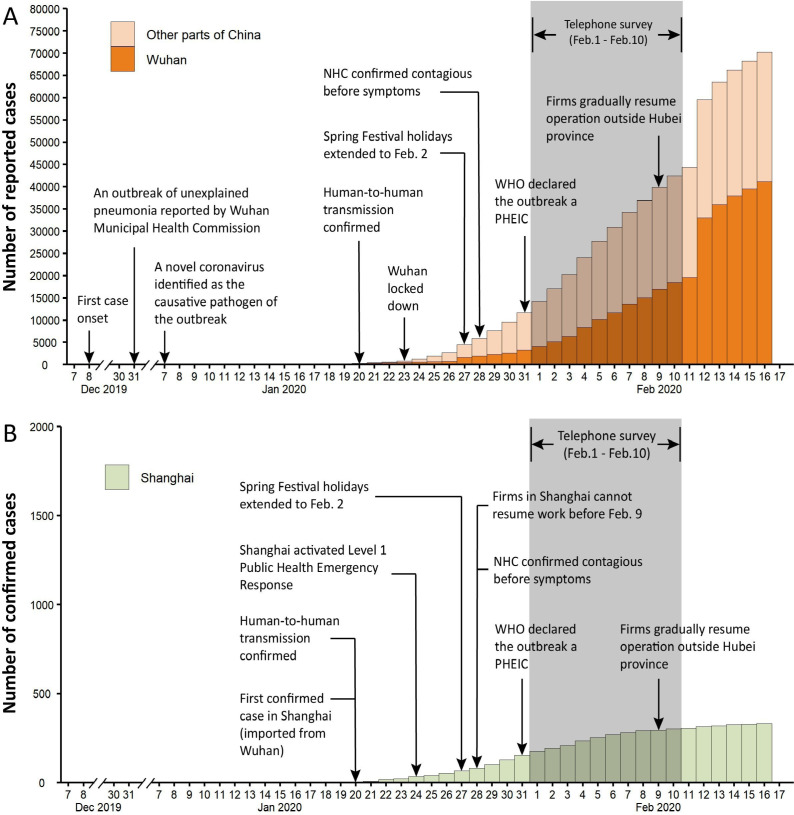

A population-based mobile phone interview was carried out between 1 February and 10 February 2020. The cities, Wuhan and Shanghai, were selected to represent diverse exposures to the threat of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Wuhan is the hardest-hit city, and the earliest city put under quarantine in China; by contrast, Shanghai is one of the largest cities in the country, and was estimated to have received the largest number of infected travellers from Wuhan.20 21 Before our survey, Wuhan confirmed 3215 cases,22 accounting for 27.3% of all cases across China;23 Shanghai reported 153 cases, 68 (44.4%) of them from non-local residents.24 Figure 1 illustrates the timeline of the outbreak progression compared with our survey dates.

Figure 1.

The timeline of the COVID-19 outbreak compared with the survey dates is presented for Wuhan and other parts of China (Panel A) and Shanghai (Panel B). Note that different scales are used in the two panels. The vertical axis for Panel A is the number of reported cases and that for Panel B is the number of confirmed cases. Diagnostic criteria were changed in Hubei Province (Wuhan is the capital city of Hubei Province) on 12 February 2020. Since then confirmed cases are based on clinical diagnosis instead of laboratory testing in Hubei province. NHC, National Health Commission of China; PHEIC, Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

The survey was conducted by well-trained interviewers with 1011 residents of Wuhan (n=510) and Shanghai (n=501) using a computerised random digit dialling system. The sample size provided us with a sample error of 5%. The system supported random generation of mobile numbers that were registered in the study cities, according to digit combination rules. Proportional quota sampling, based on age and sex distributions derived from the 2010 National Census of China, was used to ensure a demographically representative sample of the general population in each city. Calls were placed three times at different hours on the same day before being classified as invalid. Local residents aged 18 years and above who were currently living in the selected cities were eligible to participate. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants. Calls were monitored and reviewed to assure the interview quality. Participants were assigned an anonymous code based on their recruitment orders. Only members of the research team were authorised to access the data. All recorded audios will be confidentially destroyed after the completion of this study. Online supplemental figure S1 presents the flow chart of participant recruitment.

bmjopen-2020-040910supp001.pdf (768.9KB, pdf)

Anxiety

Anxiety was assessed using the 7-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7). The tool is a brief self-reported scale that has demonstrated good reliability and validity in the general population.25–28 Participants were asked to answer how frequently they had been bothered by various symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The scale accordingly produced summary GAD Scores ranging from 0 to 21. Respondents that scored 10 and above were identified as having moderate or severe anxiety.25

Precautionary behaviours

Participants were asked three sets of questions regarding their frequency of wearing a face mask when going out, frequency of immediate handwashing when returning home and average handwashing duration. In each set, the first question asked about behaviours in the usual days before 31 December 2019, when an unknown pneumonia outbreak related to later identified SARS-CoV-2 was first reported; the second question asked about behaviours in the past week. Response options for frequency questions were never (scored as 1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), usually (4), always (5) or did not go out. Respondents who did not always wear a face mask in the past week were required to provide a most possible reason. For handwashing duration questions, there were five response categories from short to long (scored as 1 to 5), for less than 10 s, 10–19 s, 20–39 s, 40–59 s or 60 s and above, respectively. Respondents whose answers for behaviours in the past week scored higher than those in the usual days were categorised as increased frequency or duration of the aforementioned behaviours.

Three questions regarding avoidance behaviours (avoided eating out, avoided taking public transportation, reduced visits to public places) and another three regarding recommended behaviours (rescheduling travel plans, increasing surface cleaning and maintaining better indoor ventilation) in response to the outbreak were raised to the respondents. Possible responses were yes or no.

To capture possible overreaction of the public, a supplementary question was asked ‘In the past week, have you ever purchased or tried to purchase goggles for the purpose of protection against infection with SARS-CoV-2?’ with two possible responses, yes or no.

Perceptions

Two items (frequent handwashing, and wearing a face mask) were used to assess whether participants believed that certain measures would reduce their risk of catching COVID-19, with possible response options being ineffective (1), even (2) or effective (3). The confidence of the public was assessed by asking if they agreed with the statement ‘I believe that I can take measures to protect myself against COVID-19’ with five response options from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Four items assessed perceived threats of COVID-19. Participants were asked ‘how likely do you think you will contract COVID-19 over the next month’ with five responses from very unlikely (1) to very likely (5), and ‘how serious do you think the infection would be if you contracted it’ with five options from very mild (1) to very serious (5). Participants were also required to report relative transmissibility and severity to SARS in 2003 with five response categories being much lower (1), lower (2), similar (3), higher (4) or much higher (5).

Three items assessed how well informed the public were. Participants were asked ‘whether you have received and read the information brochure about COVID-19 from the government and medical experts’ with two response options (yes or no). They were then required to provide responses to the statement ‘information that I received about the COVID-19 outbreak is sufficient’ with five options from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). To assess the impact of mixed information during the outbreak, participants were asked to report the frequency of feeling confused or bothered about the reliability of the information that they received. Response options ranged from never (1) to always (5).

Personal characteristics

Personal characteristics were collected in the following dimensions: sex, age, working status, perceived household income level, whether experienced symptoms (cough and fever) during the past 2 weeks, whether has friends or relatives with symptoms in the past 2 weeks, and whether there had been confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19 in their neighbourhoods.

Analyses

Online supplemental figure S2 summarises all variables collected in this study and presents hypothetical links among psychological and behavioural outcomes, perception variables, and personal characteristics. Descriptive analysis was performed to report the counts of each response option of the aforementioned questions. Differences across cities were examined using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests (when applicable). Prevalence of anxiety, precautionary behaviours and perceptions at the population level was obtained using poststratification weighting, based on age and sex distribution from the 2010 National Census of China. The primary outcomes were moderate or severe anxiety (GAD-7 Score ≥10), always wearing a face mask when going out, always washing hands immediately when returning home, handwashing duration over 40 s as recommended by WHO,29 and engaged in all recommended and avoidance behaviours. Multivariable logistic regression models were first used to estimate associations between personal characteristics and primary outcomes. These models adjusted for personal characteristics were then used to investigate perception factors (in the form of continuous scores) associated with the primary outcomes. Analyses were carried out using Stata V.14 for Windows.

Patient and public involvement

The public was involved in this study as participants of the telephone survey. This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not involved in the development of the research questions and outcome measures, or design, recruitment, conduct and writing of the study.

Results

Sample characteristics

Overall, 18 576 randomly generated digit numbers were selected and placed. Of these, 7341 calls were answered; of these, 5650 declined the participation invitation, 505 were ineligible, 185 dropped before completion, leaving 1011 respondents that successfully completed the interview. The response rate was 13.8% (1011/7341) (see online supplemental figure S1). Residents in Wuhan (34.5%) reported a much higher rate of living in neighbourhoods with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases than those in Shanghai (6.4%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Personal characteristics and associations with psychological and behavioural responses

| Wuhan | Shanghai | Moderate or severe anxiety | In the past week… | ||||

| Always wore a face mask when they went out | Always washed hands immediately when they returned | Handwashing duration above 40 s | Followed all recommended and avoidance behaviours | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Male | 255 (50.0) | 255 (48.7) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | 0.6* (0.4 to 0.9) | 0.5† (0.4 to 0.8) | 0.7† (0.5 to 0.9) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) |

| Age group, years | |||||||

| 18–24 | 89 (21.6) | 75 (13.9) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 25–39 | 161 (28.1) | 176 (33.3) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.1) | 1.6 (0.7 to 3.9) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.5) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.5) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.1) |

| 40–59 | 197 (35.4) | 165 (33.7) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.9) | 1.6 (0.6 to 3.9) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.9) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.8) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.3) |

| 60+ | 63 (15.0) | 85 (19.1) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.1) | 3.1* (1.1 to 8.9) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.0) | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.3) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) |

| Educational attainment | |||||||

| Junior school and below | 27 (6.1) | 38 (11.4) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| High school equivalent | 110 (20.9) | 72 (15.0) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.8) | 0.3* (0.1 to 0.8) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.1) | 1.6 (0.8 to 3.1) |

| College equivalent | 355 (68.9) | 337 (66.2) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.8) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.3) | 0.4 (0.2 to 1.1) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7) |

| Graduate and above | 18 (4.1) | 54 (7.4) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.4) | 6.4 (0.7 to 56.1) | 0.8 (0.2 to 3.1) | 1.2 (0.5 to 2.7) | 0.8 (0.4 to 2.0) |

| Employed | 362 (66.1) | 359 (70.3) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.5) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.2) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.1) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.7) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4) |

| Married | 383 (71.2) | 344 (70.4) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.2) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) |

| Income | |||||||

| Below median | 116 (24.1) | 97 (19.3) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Median | 329 (63.4) | 306 (61.4) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.1) | 1.2 (0.8 to 2.0) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.7) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.8) |

| Above median | 65 (12.5) | 98 (19.3) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.1) | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.8) | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.0) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) |

| Experienced symptoms | 63 (11.8) | 51 (10.0) | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.9) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.6) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.9) | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.0) | 0.6* (0.4 to 1.0) |

| Friends with symptoms | |||||||

| No | 437 (86.5) | 464 (92.8) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 63 (11.7) | 36 (7.1) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 4.0* (1.3 to 12.3) | 1.4 (0.6 to 3.1) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.5) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) |

| Don’t know | 10 (1.8) | 1 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1 to 2.1) | 0.3 (0.1 to 2.0) | 1.1 (0.1 to 14.3) | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.9) | 1.3 (0.3 to 4.8) |

| Suspected cases in neighbourhood | |||||||

| No | 261 (51.6) | 413 (82.8) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 176 (32.5) | 32 (6.3) | 1.7† (1.2 to 2.6) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.1) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.6* (0.4 to 0.9) |

| Don’t know | 73 (16.0) | 56 (11.0) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) | 1.7 (0.8 to 3.7) | 1.6 (0.8 to 3.3) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) |

| City | |||||||

| Wuhan | - | - | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Shanghai | - | - | 0.6† (0.5 to 0.9) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) | 0.4† (0.3 to 0.6) |

Columns (1) and (2) report counts and frequencies of each variable value. Columns (3)-(7) present multivariable regression results. Poststratification weights were used in prevalence calculation and regressions.

*For significance at the 5% level.

†For significance at the 1% level.

Psychological and behavioural outcomes

Around 32.8% of Wuhan residents and 20.5% of Shanghai residents were identified with moderate or severe anxiety. The prevalence was significantly higher in Wuhan (p<0.001) (Panel A of table 2).

Table 2.

Anxiety, behavioural responses and perceptions during the novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan and Shanghai

| Wuhan (n=510) | Shanghai (n=501) | P value | |

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Panel A: Anxiety levels | |||

| Moderate or severe anxiety (GAD-7 Score ≥10) | 167 (32.8) | 102 (20.5) | <0.001 |

| Panel B: Behavioural responses | |||

| Always wore a face mask when they went out* | 329 (86.7) | 381 (88.2) | 0.212 |

| Always washed hands immediately when they returned* | 306 (79.6) | 372 (86.2) | 0.01 |

| Handwashing duration above 40 s | 192 (37.0) | 176 (35.5) | 0.406 |

| More often wore a face mask when they went out* | 355 (86.2) | 373 (86.7) | 0.853 |

| More often washed hands immediately when they returned* | 164 (41.7) | 157 (36.4) | 0.073 |

| Longer handwashing duration | 260 (51.0) | 200 (40.2) | <0.001 |

| Followed all recommended and avoidance behaviours | 401 (78.7) | 320 (64.3) | <0.001 |

| Never went out last week | 124 (22.4) | 69 (13.6) | <0.001 |

| Purchased goggles for prevention | 143 (28.8) | 105 (20.8) | 0.009 |

| Panel C: Perception variables | |||

| Perceived efficacy of wearing a face mask | 0.233 | ||

| Ineffective | 7 (0.6) | 4 (0.8) | |

| Even | 35 (6.5) | 47 (9.4) | |

| Effective | 472 (93.0) | 450 (89.8) | |

| Perceived efficacy of washing hands frequently | 0.269 | ||

| Ineffective | 3 (0.8) | 7 (1.4) | |

| Even | 71 (13.7) | 80 (15.8) | |

| Effective | 436 (85.5) | 414 (82.8) | |

| Self-perceived risk† | 0.033 | ||

| Very unlikely | 85 (17.1) | 93 (19.7) | |

| Unlikely | 190 (42.2) | 230 (48.7) | |

| Even | 105 (22.0) | 91 (19.0) | |

| Likely | 72 (15.4) | 49 (10.4) | |

| Very likely | 15 (3.2) | 10 (2.2) | |

| Self-perceived severity if contracted‡ | <0.001 | ||

| Very mild | 158 (39.5) | 104 (25.9) | |

| Mild | 142 (33.7) | 166 (40.9) | |

| Moderate | 50 (14.0) | 53 (12.9) | |

| Serious | 32 (7.8) | 60 (15.1) | |

| Very serious | 16 (4.9) | 20 (5.1) | |

| Transmissibility compared with SARS | <0.001 | ||

| Much lower | 13 (2.7) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Lower | 17 (3.6) | 8 (1.6) | |

| Even | 59 (12.6) | 39 (7.6) | |

| Higher | 170 (33.8) | 172 (34.4) | |

| Much higher | 251 (47.3) | 281 (56.3) | |

| Severity compared with SARS | 0.37 | ||

| Much lower | 13 (2.5) | 12 (2.4) | |

| Lower | 66 (13.6) | 75 (14.7) | |

| Even | 131 (27.5) | 136 (26.8) | |

| Higher | 158 (30.6) | 127 (25.7) | |

| Much higher | 142 (25.9) | 151 (30.5) | |

| Confidence on taking measures to protect myself | 0.302 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.7) | |

| Disagree | 13 (2.3) | 14 (2.8) | |

| Even | 47 (9.3) | 49 (9.7) | |

| Agree | 253 (48.1) | 276 (54.9) | |

| Strongly agree | 195 (39.9) | 159 (31.9) | |

| Received and read information brochures | 490 (95.6) | 446 (89.4) | <0.001 |

| Sufficient information | 0.937 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 4 (0.6) | 7 (1.3) | |

| Disagree | 23 (4.7) | 23 (5.8) | |

| Even | 65 (13.0) | 65 (10.0) | |

| Agree | 221 (43.2) | 221 (50.0) | |

| Strongly agree | 197 (38.5) | 197 (32.9) | |

| Confused about information reliability | 0.003 | ||

| Never | 158 (31.7) | 215 (43.2) | |

| Rare | 150 (29.0) | 121 (24.2) | |

| Sometimes | 124 (24.4) | 102 (20.0) | |

| Usually | 46 (9.1) | 41 (8.2) | |

| Always | 32 (5.8) | 22 (4.4) | |

*The total number of respondents was 386 in the Wuhan sample and 432 in the Shanghai sample because 124 and 69 participants reported ‘never went out last week’, respectively, in the above samples.

†The total number of respondents was 457 in the Wuhan sample and 473 in the Shanghai sample because 43 Wuhan participants and 28 Shanghai participants refused to answer.

‡The total number of respondents was 398 in the Wuhan sample and 403 in the Shanghai sample because 112 Wuhan participants and 98 Shanghai participants refused to answer.

GAD-7, 7-item generalised anxiety disorder scale.

In both cities, the majority (86.2%–88.2%) of residents reported increased frequency of wearing a face mask and always wearing a face mask when they went out; there was no discernible differences across cities. Around 79.6% of Wuhan residents and 86.2% of Shanghai residents reported they always washed hands immediately when they returned home. The proportion was significantly higher in Shanghai (p=0.010). A significantly higher proportion (p<0.001) of Wuhan residents (51.0%) than their Shanghai counterparts (40.2%) reported longer handwashing duration. However, only 35.5% (Shanghai)−37.0% (Wuhan) residents followed the WHO recommendation, with no statistically significant differences across cities (Panel B of table 2).

About 78.7% of Wuhan residents and 64.3% of Shanghai residents engaged in all six recommended and avoidance behaviours due to the COVID-19 outbreak (Panel B of table 2). A close inspection on each behaviour showed a high compliance rate of above 90%, except for increased surface cleaning, which was driving the significant differences in this outcome across cities (see online supplemental table S1). Moreover, a significantly higher proportion (p<0.01) of Wuhan than Shanghai residents reported never went out last week (22.4% vs 13.6%) and purchased or tried to purchase goggles for prevention purpose (28.8% vs 20.8%).

Perceptions

Overall, above 80% of residents perceived wearing a face mask and frequent handwashing as effective precautionary measures, with no statistical significant differences across cities. Generally, Wuhan residents reported significantly higher self-perceived risk (p=0.033) of contracting the disease than their counterparts in Shanghai; however, their perceived severity and relative transmissibility to SARS were significantly lower (p<0.001). No differences were found between the two cities in terms of perceived harm to body compared with SARS. Moreover, respondents aged 40 years and above, who presumably have clearer memory of SARS, reported higher (p<0.001) perceived relative severity than other age groups in Shanghai; similar results were not found in Wuhan (see online supplemental table S2). The majority of the residents agreed or strongly agreed with having confidence on taking measures to protect themselves. We detected no statistically significant differences across cities in this domain (Panel C of table 2).

Around 95.6% of Wuhan residents had read the information brochures of COVID-19 from the government or medical experts. The proportion was significantly lower (p<0.001) but still very high in Shanghai (89.4%). The majority of the respondents in both cities thought that the information that they received was sufficient, without discernible differences. In addition, Wuhan residents were significantly more often confused about the reliability of the information that they received (p=0.003). Only 31.7% of Wuhan residents never felt bothered about this issue. In contrast, the corresponding figure in Shanghai was 43.2% (Panel C of table 2).

Personal variables associated with psychological and behavioural responses

Regarding moderate or severe anxiety, Shanghai residents had significantly lower odds (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.5 to 0.9); living in neighbourhoods with confirmed or suspected cases was the strongest positive predictor (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.6); no other individual characteristics were found to be associated with the outcome.

The odds of always wearing a face mask, always washing hands immediately and handwashing duration above 40 s were significantly lower among men. We found no consistent evidence that age, educational attainment, working status and marital status were closely associated with the aforementioned precautionary behaviours. Individuals aged 60 years and above and those who had friends with symptoms had higher odds of always wearing a face mask when they went out; however, similar results were not found for handwashing outcomes.

Perception factors associated with psychological and behavioural responses

We found that higher perceived risk and severity of contracting COVID-19, higher perceived relative transmissibility and harm to SARS, and more confusion about information reliability were all significantly and positively associated with higher odds of moderate or severe anxiety (table 3); among them, perceived relative harm to SARS and confusion about information reliability exerted the largest impact. In contrast, stronger self-confidence and perceived efficacy of wearing a face mask were significantly associated with lower odds.

Table 3.

Perception factors associated with anxiety and behavioural responses

| Perception factors | Moderate or severe anxiety | Always wore a face mask when they went out | Always washed hands immediately when they returned | Handwashing duration above 40 s | Followed all recommended and avoidance behaviours |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Efficacy of washing hands frequently | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.1) | - | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.0) | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.0) | - |

| Efficacy of wearing a face mask | 0.6* (0.4 to 0.9) | 2.4* (1.4 to 4.4) | - | - | - |

| Perceived risk | 1.6* (1.3 to 1.9) | 0.8† (0.6 to 1.0) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.8† (0.7 to 1.0) |

| Perceived severity if contacted | 1.3* (1.1 to 1.5) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) |

| Transmissibility compared with SARS (in 2003) | 1.6† (1.3 to 2.0) | 1.3* (1.1 to 1.7) | 1.5* (1.2 to 1.8) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Harm to body compared with SARS (in 2003) | 1.8* (1.5 to 2.1) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.2† (1.0 to 1.4) |

| Self-confidence | 0.6† (0.6 to 0.7) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) |

| Received and read information brochure | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.2) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.6) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.3) | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.7) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.7) |

| Sufficient information | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.5) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| Confused about information reliability | 1.7† (1.5 to 1.9) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) |

Each column of each row presents a separate multivariable logistic regression result. In all specifications, personal variables as listed in table 1 are controlled for.

*For significance at the 1% level.

†For significance at the 5% level.

SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Perceived efficacy of the corresponding precautionary behaviour was the strongest positive predictor of always wearing a face mask, but it was not associated with the odds of always washing hands immediately. Perceived relative transmissibility compared to SARS was a significant predictor of both outcomes. We found no perception factors examined in this study associated with the odds of handwashing duration above 40 s. Perceived relative harm to SARS was associated with higher odds of following all recommended and avoidance behaviours. Individuals who received and read information brochures were more likely to increase their frequency of immediate handwashing when back home (table 3). Higher perceived relative harm to SARS was the only factor with significant explanatory power for goggles purchase behaviour (see online supplemental table S3).

Discussion

Our study provided new evidence on anxiety and precautionary behaviours in response to disease outbreaks by conducting a population-based mobile phone survey in China during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak and comparing results from two cities with various exposures to the disease. We found that a significantly higher proportion of Wuhan residents than their Shanghai counterparts reported moderate or severe anxiety and followed all recommended and avoidance behaviours. Around 79.6%–88.2% of residents reported always wearing a face mask when they went out and always washing hands immediately when they returned home during the past week; generally, Wuhan residents were not more responsive to the outbreak in terms of changes in the above two dimensions.

Our results suggested a high level of anxiety and prevalence of strict precautionary behaviours, regardless of the quarantine status of the city. The prevalence of moderate or severe anxiety has been four to five times of its normal level in urban China.27 28 The majority of the residents in both cities changed their face mask wearing and handwashing behaviours and practised all recommended and avoidance behaviours. These results contradict findings in UK during the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic,7 but are much sizeable than those in Hong Kong during SARS and influenza A (H1N1).4 8 10

Consistent with a previous study, our results showed that perceived harm and information reliability were significantly associated with higher anxiety levels.7 Perceived transmissibility was a positive predictor of taking strict personal precautionary measures. However, our findings further showed that in the case of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, information reliability was not significantly associated with precautionary behaviours and only perceived efficacy of wearing a face mask was significantly associated with the corresponding behaviour. We did not observe a similar association for handwashing.

Moreover, we also found evidence for unwarranted precautionary behaviour in coping with a novel disease, which was less documented in the literature.5 According to the National Health Commission experts, goggles are an unnecessary protective equipment for people other than medical staff on the front line of the COVID-19 outbreak. However, 20.8%–28.8% of residents purchased or tried to purchase goggles for protection purposes after they learnt from social media that a doctor suspected that lack of eye protection might have led to his infection.

Discrepancies in the findings may be attributable to two main reasons. First, compared with studies regarding other diseases, we documented higher perceived susceptibility and severity in the case of COVID-19. We translated our results into comparable scales and found that the perceived chance of infection (12.5%–18.6%) was greater than that during H7N9 in urban China (1.0%–2.6%),11 and SARS in Hong Kong (3.9%–14.3%);4 and the perceived relative severity to SARS was four times higher than that of H7N9 in urban China (8.9%–11.4%).11 Higher perceived risk and harm of COVID-19 were positively associated with favourable responses in behaviours, and led to significantly higher anxiety levels and possible overreaction among the general public.

Second, strong involvement from the Chinese government at all levels had fuelled high compliance with avoidance behaviours. Measures such as temporary closing down of public transportation in Wuhan and adopting strict closed-off community management in both cities largely reduced unnecessary travel. These measures are also responsible for the limited observed heterogeneity in uptake and changes of precautionary behaviours across cities and individuals. In contrast, corresponding findings documented in the literature were mainly driven by voluntary actions,5 9 30 31 which may also explain the discrepancies in the size of public responses.

Our findings also yielded several important public implications. First, residents in China might have placed face mask wearing in a more important position than handwashing. Perceived efficacy of face mask wearing was associated with lower odds of moderate or severe anxiety, however, perceived efficacy of frequent handwashing was not. Although the majority of the residents reported always washing hands immediately when they returned home, only 40.2%–51.0% residents reported longer handwashing duration. Moreover, the proportion of handwashing duration over 40 s as recommended by WHO was relatively low at 35.5%–37.0%. These results suggested that awareness of hand hygiene in China has been low, which calls for more education in the community. Fortunately, our results also showed that having received and read information brochures was positively associated with odds of longer handwashing duration, suggesting that education programmes with a focus on hand hygiene procedures could be effective for addressing this issue.

Second, providing the public with timely and accurate information is crucial for addressing the psychological effects of contagious disease outbreaks. Public confusion about the reliability of information that they received was the strongest predictor of moderate or severe anxiety. Besides, around 56.8%–68.3% of individuals were ever bothered by this issue, and the prevalence of this issue was significantly more common among people subject to quarantine in Wuhan, suggesting stronger desire for facts.32

Our study has a number of limitations. First, in order to investigate public response rates in the immediate aftermath of the major public health crisis, we shortened our survey questionnaire and chose to use random digit dialling with quota sampling to obtain demographically representative samples for both selected cities. We deliberately did not select times of handwashing as a key behaviour measure. That is becuase people having largely reduced going out during the extended national holidays while embracing remote work, resulting in less times of handwashing than in usual days, makes this measure less valid. Second, we asked respondents to recall some of their behaviours during the usual days before December 2019. Their answers might suffer recall bias. Third, although our response rate was not low compared with a telephone survey, non-response bias on the basis of interest in the topic may compromise our findings. Fourth, our sample spanned a period where number of COVID-19 cases increased drastically, which may lead to an underestimation bias in the prevalence of anxiety and precautionary behaviours. We conducted robustness checks by including linear time trend in the regressions and found that results were qualitatively similar (results available on request).

Conclusions

In conclusion, during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak, prevalence of moderate or severe anxiety was four to five times of its normal level in urban China. The majority of residents followed all recommended and avoidance behaviours, reported always wearing a face mask when they went out and always washing hands immediately when they returned home, regardless of the quarantine status of their living cities. Perceived harm of the disease was the strongest predictor of moderate or severe anxiety, followed by confusion about information reliability. Public awareness of hand hygiene was less optimal. Our results support efforts for timely dissemination of accurate and reliable information and programmes with a focus on handwashing education.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark Jit from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for his valuable comments. The authors also thank Xinyu Wang, Shengyi Pan, Zihan Xu, Longfei Feng, Kaiyue Ren, Yifan Cheng, Abudukelimu Nazhakaiti, Zhiqiang Qu, Geshu Zhang, Ji Geer Guliyeerke, Qian Lv, Biao Wang, Linqing Zhou and Cong Ma from School of Public Health, Fudan University for providing assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: HY conceptualised the study design. MQ, ZH and YL developed the survey questionnaire and collected data. MQ and QW analysed data. MQ interpreted results and wrote the manuscript. PW, BJC and HY edited the manuscript.

Funding: HY acknowledges financial support from the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 81525023), National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2018ZX10201001-010, No. 2017ZX10103009-005, No. 2018ZX10713001-007). MQ acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71704027) and Shanghai Municipal Education Commission and Shanghai Education Development Found for Chenguang Program (No. 17CG03). The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Competing interests: HY has received research funding from Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Yichang HEC Changjiang Pharmaceutical Company and Shanghai Roche Pharmaceutical Company. None of that research funding is related to COVID-19. BJC has received honoraria from Roche and Sanofi. All other authors report no competing interests. All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest Form.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the institutional review board at School of Public Health, Fudan University (IRB#2020-01-0801).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Full top line results for the survey are available from H.Y. at yhj@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. . A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2020;382:727–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Health Commission Latest situation of new coronavirus pneumonia as of April 19 2020 (in Chinese). Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202004/2d391a171acc4624a50a1188c8de7361.shtml

- 3.World Health Organization Available: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200405-sitrep-76-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=6ecf0977_4

- 4.Lau JTF, Yang X, Tsui H, et al. . Monitoring community responses to the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: from day 10 to day 62. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:864–70. 10.1136/jech.57.11.864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brug J, Aro AR, Oenema A, et al. . Sars risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:1486–9. 10.3201/eid1008.040283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, et al. . The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry 2009;54:302–11. 10.1177/070674370905400504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin GJ, Amlôt R, Page L, et al. . Public perceptions, anxiety, and behaviour change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: cross sectional telephone survey. BMJ 2009;339:b2651. 10.1136/bmj.b2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeung NCY, Lau JTF, Choi KC, et al. . Population Responses during the Pandemic Phase of the Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Epidemic, Hong Kong, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23:813–5. 10.3201/eid2305.160768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayham J, Kuminoff NV, Gunn Q, et al. . Measured voluntary avoidance behaviour during the 2009 A/H1N1 epidemic. Proc Biol Sci 2015;282:20150814. 10.1098/rspb.2015.0814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau JTF, Griffiths S, Choi KC, et al. . Avoidance behaviors and negative psychological responses in the general population in the initial stage of the H1N1 pandemic in Hong Kong. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:139. 10.1186/1471-2334-10-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Cowling BJ, Wu P, et al. . Human exposure to live poultry and psychological and behavioral responses to influenza A(H7N9), China. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:1296–305. 10.3201/eid2008.131821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu P, Wang L, Cowling BJ, et al. . Live Poultry Exposure and Public Response to Influenza A(H7N9) in Urban and Rural China during Two Epidemic Waves in 2013-2014. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137831. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu P, Fang VJ, Liao Q, et al. . Responses to threat of influenza A(H7N9) and support for live poultry markets, Hong Kong, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:882–6. 10.3201/eid2005.131859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng C, Tang CS-K. The psychology behind the masks: psychological responses to the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in different regions. Asian J Soc Psychol 2004;7:3–7. 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2004.00130.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vartti A-M, Oenema A, Schreck M, et al. . SARS knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors: a comparison between finns and the Dutch during the SARS outbreak in 2003. Int J Behav Med 2009;16:41–8. 10.1007/s12529-008-9004-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Zwart O, Veldhuijzen IK, Elam G, et al. . Perceived threat, risk perception, and efficacy beliefs related to SARS and other (emerging) infectious diseases: results of an international survey. Int J Behav Med 2009;16:30–40. 10.1007/s12529-008-9008-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. . Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, et al. . Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2010185. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong X, Zheng K, Tang M, et al. . Prevalence and factors associated with depression and anxiety of hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

- 20.Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet 2020;395:689–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Read JM, Bridgen JRE, Cummings DAT, et al. . Novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV: early estimation of epidemiological parameters and epidemic predictions, 2020. Available: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.01.23.20018549v2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Health Commission of Hubei Province Update on the outbreak of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia as of 31 January 2020 (in Chinese). Available: http://wjw.hubei.gov.cn/fbjd/dtyw/202002/t20200201_2017100.shtml [Accessed 15 Feb 2020].

- 23.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China Update on the outbreak of novel coronavirus-related pneumonia as of 31 January 2020 (in Chinese). Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202002/84faf71e096446fdb1ae44939ba5c528.shtml [Accessed 15 Feb 2020].

- 24.Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Shanghai municipal administration of traditional Chinese medicine. 18 new confirmed cases of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Shanghai (in Chinese). Available: http://wsjkw.sh.gov.cn/yqtb/20200201/c109479681e64952824c04eae3145e89.html [Accessed 15 Feb 2020].

- 25.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. . A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. . Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care 2008;46:266–74. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo X, Meng Z, Huang G, et al. . Meta-analysis of the prevalence of anxiety disorders in mainland China from 2000 to 2015. Sci Rep 2016;6:28033. 10.1038/srep28033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu W, Singh SS, Calhoun S, et al. . Generalized anxiety disorder in urban China: prevalence, awareness, and disease burden. J Affect Disord 2018;234:89–96. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization Hand hygiene: why how & when? Available: https://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Hand_Hygiene_Why_How_and_When_Brochure.pdf [Accessed 15 Feb 2020].

- 30.Fenichel EP, Kuminoff NV, Chowell G. Skip the trip: air travelers’ behavioral responses to pandemic influenza. PLoS One 2013;8:e58249. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadique MZ, Edmunds WJ, Smith RD, et al. . Precautionary behavior in response to perceived threat of pandemic influenza. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:1307–13. 10.3201/eid1309.070372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubin GJ, Wessely S. The psychological effects of quarantining a City. BMJ 2020:m313 10.1136/bmj.m313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-040910supp001.pdf (768.9KB, pdf)