Abstract

Background

Glycated albumin (GA) is a marker of short-term glycemic control and is strongly associated with the occurrence of diabetes. Previous studies have shown an association between GA and the effect of clopidogrel therapy on ischemic stroke. However, limited information is available regarding this relationship in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients. In this study, we evaluated the effect of GA on platelet P2Y12 inhibition by clopidogrel in patients with ACS.

Methods

Consecutive Chinese patients with ACS who received loading or maintenance doses of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin were recruited. At least 12 h after the patient had taken the clopidogrel dose, thromboelastography (TEG) and light transmittance aggregometry (LTA) were used to calculate the quantitative platelet inhibition rate to determine clopidogrel-induced antiplatelet reactivity. A prespecified cutoff of the maximum amplitude of adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength > 47 mm plus an ADP-induced platelet inhibition rate < 50% assessed by TEG or ADP-induced platelet aggregation > 40% assessed by LTA to indicate low responsiveness to clopidogrel were applied for evaluation. Patients were categorized into two groups based on a GA level of 15.5%, the cutoff point indicating the development of early-phase diabetes. Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to assess the interaction of GA with clopidogrel antiplatelet therapy.

Results

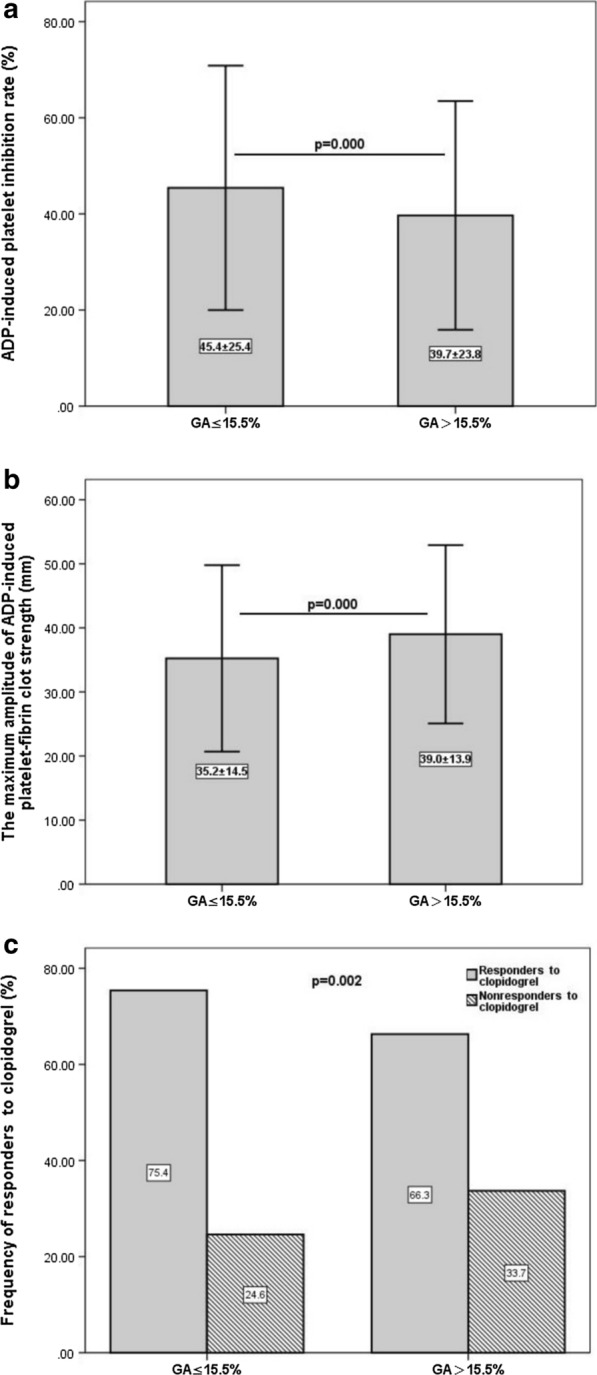

A total of 1021 participants were evaluated, and 28.3% of patients (289 of 1021) had low responsiveness to clopidogrel assessed by TEG. In patients with elevated GA levels, low responsiveness to clopidogrel assessed by TEG was observed in 33.7% (139 of 412) of patients, which was a significantly higher rate than that in the lower-GA-level group (24.6%, P = 0.002). According to multivariate linear regression analysis, a GA level > 15.5% was independently associated with low responsiveness to clopidogrel after adjustment for age, sex and other conventional confounding factors. This interaction was not mediated by a history of diabetes mellitus. A GA level ≤ 15.5% was associated with a high positive value [75.4%, 95% CI 73.0–77.6%] for predicting a normal responsiveness to clopidogrel.

Conclusions

GA could be a potential biomarker to predict the effects of clopidogrel antiplatelet therapy in ACS patients and might be a clinical biomarker to guide DAPT de-escalation.

Keywords: Glycated albumin, Acute coronary syndrome, Clopidogrel

Background

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a type of P2Y12 inhibitor is the cornerstone of preventive treatment for patients who present with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and it has been recommended by guidelines to prevent thrombotic complications and improve prognosis [1–3]. In ACS patients, although ticagrelor and prasugrel are recommended over clopidogrel [3], clopidogrel is still used widely because it is associated with a lower risk of major bleeding [4, 5] and lower financial burden [6].

However, the pharmacodynamic effects of clopidogrel are influenced by many clinical and genetic factors [7–9], and a considerable number of patients are poorly responsive to clopidogrel and have a higher risk of thrombotic events than normal responders [10, 11]. Therefore, while DAPT de-escalation in ACS patients may be considered an alternative treatment regimen to reduce bleeding risk and/or cost, some patients may be at risk for thrombotic complications [12, 13]. On the basis of which guideline is being followed, de-escalation may be performed based on clinical judgment alone, or it may be guided by platelet function testing or CYP2C19 genotyping [13]. Clinical markers are useful tools to help the doctors to make correct clinical judgments and select the most appropriate strategy of treatment.

Patients with diabetes mellitus have been found to be less sensitive to clopidogrel therapy than nondiabetic patients [14, 15], but hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), the standard measure of long-term (2–3 months) glucose control, may not be a good predictor of low responsiveness to clopidogrel [16–18]. Glycated albumin (GA), a marker of shorter-term (2–4 weeks) glycemic control, is strongly associated with the occurrence of diabetes [19]. Consequently, GA levels might be useful to predict ACS patients’ response to antiplatelet therapy and be a good clinical biomarker to guide DAPT de-escalation.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the contributions of GA to platelet P2Y12 inhibition induced by clopidogrel as assessed by thromboelastography (TEG) and light transmittance aggregometry (LTA) in patients with ACS. Both platelet function tests can be used to calculate the quantitative platelet inhibition rate to determine low responsiveness to clopidogrel [20, 21].

Methods

Study design and patients

All patients with ACS who received a maintenance dose of clopidogrel (75 mg, once daily) and aspirin (100 mg, once daily) in-hospital and out-hospital were consecutively recruited in the Department of Cardiology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, from March 2018 to July 2019. Clopidogrel was given as either a dose of 300 mg at least 12 h before platelet function testing or a dose of 75 mg for at least 5 days before platelet function testing [3, 18, 20]. The major exclusion criteria included the following: patient age < 18 years old, symptoms of severe heart failure (New York Heart Association class III and above), severely impaired liver or renal function before the procedure (serum alanine aminotransferase > 2.5 times the upper limit of normal, serum creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL), known contraindication to aspirin or clopidogrel treatment, a history of bleeding diathesis or gastrointestinal bleeding, and a history of cerebral hemorrhage or cavum subarachnoid bleeding. The present study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 2018075X) of Beijing Anzhen Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal proxies.

Platelet function tests: thromboelastography and light transmittance aggregometry

Blood samples for platelet function tests were collected at least 12 h after the patient had taken the clopidogrel dose to ensure full antiplatelet effects. Peripheral venous whole blood was drawn by venipuncture into vacutainer tubes containing 3.2% trisodium citrate and lithium heparin (Becton–Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

A detailed description of thromboelastography has been outlined previously [21, 22]. Briefly, blood sample measurements were performed using the CFMS TEG System (LEPU Medical, Beijing, China) to detect the effects of antiplatelet therapy action via the arachidonic acid (AA) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) pathways. The CFMS TEG System (LEPU Medical, Beijing, China) relied on the measurement of thrombin-induced clot strength to enable a quantitative analysis of platelet function. The assay incorporated the use of heparin as an anticoagulant to eliminate thrombin activity in the sample. Reptilase and factor XIIIa (activator F) were used to generate a cross-linked fibrin clot to isolate the fibrin contribution to clot strength. The contribution of P2Y12 receptor pathways to clot formation could be measured by the addition of the appropriate agonist, AA or ADP. Blood was analyzed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One milliliter heparinized blood was transferred to a vial containing kaolin and mixed by inversion. Five hundred microliters of the activated blood were then transferred to a vial containing heparinase and mixed to neutralize heparin. The neutralized blood (360 μL) was immediately added to a heparinase-coated cup and assayed in the TEG System to measure the maximum amplitude of thrombin-induced clot strength (MAthrombin). Heparinized blood (340 μL) was added to a noncoated cup containing reptilase and activator F to generate a whole blood crosslinked clot in the absence of thrombin generation or platelet stimulation (MAfibrin). A third sample (340 μL) of heparinized blood was added to a nonheparinase-coated cup in the presence of the activator F and ADP (2 μmol) or AA (1 mmol/L) to generate a whole blood-crosslinked clot with platelet activation (MAADP or MAAA). ADP-induced platelet inhibition was calculated with computerized software on the basis of the formula: ADP-induced platelet inhibition rate = 100%. Low responsiveness to clopidogrel was defined as the maximum amplitude of ADP-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength (MAADP) > 47 mm plus an ADP-induced platelet inhibition rate < 50% [20, 23].

The measurement of platelet aggregation by light transmittance aggregometry was also assessed as described previously [24]. The blood-citrate tubes were centrifuged at 120g for 5 min to recover platelet-rich plasma and further centrifuged at 850g for 10 min to recover platelet-poor plasma. Platelet-rich plasma and platelet-poor plasma were used as a reference for establishing the 100% and baseline optical density, respectively. ADP (Rolf Greiner Biochemica, Flacht, Germany)-induced platelet aggregation was assessed in a 20 μmol/L solution using a ChronoLog aggregometer (ChronoLog Model 700; ChronoLog, Havertown, Pennsylvania, USA). Aggregation was expressed as the maximum percent change in light transmittance from baseline. The normal range of ADP-induced platelet aggregation was 50–70% in our center, and low responsiveness to clopidogrel was defined as the ADP-induced platelet aggregation > 40%, which was in agreement with that of a previous study [24].

Measurement of GA level

Venous blood was drawn from fasting patients by venipuncture into vacutainer tubes with no additives (Becton–Dickinson, San Jose, CA). The GA assay (Lucica GA-L glycated albumin assay kit, Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation, Japan) was performed in the clinical laboratory in Anzhen Hospital using an automated biochemical analyzer (Beckman AU5400 Chemistry System), and the results are expressed as the ratio of glycated albumin to albumin.

Demographic, clinical and laboratory assessments

Demographic variables included age and sex. Behavioral risk factors included body mass index (BMI, weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters) and cigarette smoking. Clinical and laboratory data included (1) presentations of ACS: unstable angina (UA), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (non-STEMI), and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI); (2) medical history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, or PCI; (3) baseline platelet count, serum lipid levels (total cholesterol [TC], low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol [LDL-C], high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol [HDL-C], triglycerides [TGs]), and creatinine levels; (4) major medications administered in the hospital: angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), β-blockers, calcium channel blocking agents (CCBs), statins, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs); and (5) glucose indexes: fasting glucose, HbA1c, glycated albumin and insulin.

Statistical analysis

Based on the hypothesis that patients with higher GA levels would exhibit an impaired response to clopidogrel, we assumed that a GA level > 15.5% was independently associated with a higher probability of low responsiveness to clopidogrel with an odds ratio (OR) = 1.8, according to a previous study assessing the relationship between ischemic stroke and GA level [25]. One previous study showed that 29.0% of patients with normal responsiveness to clopidogrel had previously or newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus [26], and we assumed that 40% of clopidogrel responders had a GA level > 15.5%. We computed the detectable ORs based on a required power of 90% and a significance level of 0.05 for comparing the rates of a GA level > 15.5% between the two kinds of clopidogrel response groups. A sample size of 492 was needed, and this procedure was performed with PASS 11 (NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA).

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation or medians with interquartile ranges and were compared using Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Normality was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Noncontinuous and categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages and were compared by using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the size of the analyzed group of patients. Pearson correlation analysis was carried out to assess the relationship between GA level and platelet aggregation. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationship between GA level and medical history of diabetes mellitus. Multivariate linear regression analysis with calculation of ORs was used to test the independent contribution of each covariate to the responsiveness to clopidogrel. ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Adjustments were made for possible confounding effects, including baseline demographic characteristics (age, sex, BMI), smoking status, comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, presentations of ACS), and laboratory examinations (platelet count, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, creatinine and GA). A 2-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study population

A total of 1021 consecutive clopidogrel-treated ACS patients were enrolled in the study. There were no missing baseline data for variables of interest. The baseline characteristics of all patients are detailed in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, 28.3% of patients (289 of 1021) had low responsiveness to clopidogrel. According to univariate analysis, they were more often female and older, and less likely to be current or former smokers. They more often had a history of hypertension and coronary artery bypass graft; had a higher baseline platelet count and levels of TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C; and a lower baseline level of creatinine. Furthermore, they had higher levels of GA (16.6 ± 3.6% vs. 15.6 ± 3.4%, P = 0.000) but did not have higher levels of fasting plasma glucose or HbA1c (6.4 ± 2.0 mmol/L vs. 6.2 ± 2.3 mmol/L, P = 0.154; 6.3 ± 1.2% vs. 6.5 ± 1.3%, P = 0.093).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the ACS patients by responsiveness to clopidogrel assessed by thromboelastography

| Responders to clopidogrel (n = 732) | Nonresponders to clopidogrel (n = 289) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, m (%) | 601 (82.1%) | 151 (52.2%) | 0.000 |

| Age, y | 59.2 ± 10.3 | 62.9 ± 9.8 | 0.000 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.9 ± 3.2 | 25.6 ± 3.2 | 0.207 |

| Medical history, n, (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 247 (33.7%) | 113 (39.1%) | 0.107 |

| Hypertension | 463 (63.3%) | 205 (70.9%) | 0.020 |

| Previous stroke | 74 (10.1%) | 39 (13.5%) | 0.120 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 55 (7.5%) | 22 (7.6%) | 0.957 |

| Previous CABG | 3 (0.4%) | 5 (1.7%) | 0.045 |

| Previous PCI | 53 (8.7%) | 27 (6.6%) | 0.236 |

| Presentations of ACS | 0.496 | ||

| Unstable angina | 669 (91.4%) | 258 (89.3%) | |

| Non-STEMI | 32 (4.4%) | 14 (4.8%) | |

| STEMI | 31 (4.2%) | 17 (5.9%) | |

| Current or previous smoking, n (%) | 440 (60.1%) | 117 (40.5%) | 0.000 |

| Baseline laboratory evaluation | |||

| PLT, × 109/L | 210.5 ± 55.2 | 234.4 ± 62.1 | 0.000 |

| TC, mmol/L | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 0.000 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 0.001 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.002 |

| TGs, mmol/L | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.590 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 72.0 ± 14.8 | 68.1 ± 17.2 | 0.000 |

| Major medication administered in hospital | |||

| ARBs, n, (%) | 110 (15.0%) | 40 (13.8%) | 0.630 |

| ACEIs, n, (%) | 161 (22.0%) | 77 (26.2%) | 0.113 |

| β-blockers, n, (%) | 510 (69.7%) | 209 (72.3%) | 0.404 |

| CCBs, n, (%) | 61 (8.3%) | 21 (7.3%) | 0.572 |

| Statins, n, (%) | 715 (97.7%) | 282 (97.6%) | 0.925 |

| PPIs, n, (%) | 369 (50.4%) | 141 (48.8%) | 0.641 |

| Glucose indices | |||

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 6.2 ± 2.3 | 6.4 ± 2.0 | 0.154 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 0.093 |

| Glycated albumin, % | 15.6 ± 3.4 | 16.6 ± 3.6 | 0.000 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.40 (1.65–3.77) | 2.54 (1.71–3.95) | 0.513 |

BMI body mass index, CABG coronary artery bypass graft, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, non-STEMI non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, PLT platelet count, TC total cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, TGs triglycerides, ARBs angiotensin receptor blockers, ACEIs angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, CCBs calcium channel blocking agents, PPIs proton pump inhibitor, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, calculated using the following formula: fasting serum insulin (μU/mL) * FPG (mmol/L)/156

Weak antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel in patients with elevated GA

Many variables could affect patients’ responsiveness to the antiplatelet activity of clopidogrel, such as age, sex, BMI, smoking status, history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, presentations of ACS, and baseline level of platelet count, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, creatinine and GA. According to multiple linear regression analysis with the multivariate model, we found that age [OR: 1.028, 95% CI (1.011 to 1.046), P = 0.002], female sex [OR: 2.964, 95% CI (1.869 to 4.700), P = 0.000], platelet count [OR: 1.006, 95% CI (1.003 to 1.009), P = 0.000] and GA > 15.5% [OR: 1.489, 95% CI (1.012 to 2.189), P = 0.043] were independently associated with low responsiveness to clopidogrel. These analyses showed that although the GA level correlated with a history of diabetes mellitus (r = 0.622, P = 0.000), the interaction of GA with clopidogrel antiplatelet therapy was not mediated by a history of diabetes mellitus.

High ADP-induced platelet aggregation in patients with elevated GA

Light transmittance aggregometry was also implemented in the current study to assess the responsiveness to clopidogrel. As shown in Additional file 1: Table S1, 30.4% of patients (310 of 1021) had low responsiveness to clopidogrel, which was correlated with ADP-induced platelet aggregation > 40%. According to univariate analysis, patients were more often female and older and less likely to have unstable angina. They had a higher baseline level of TC (3.9 ± 1.0 mmol/L vs. 3.8 ± 1.0 mmol/L, P = 0.047) and GA (16.1 ± 3.7% vs. 15.5 ± 3.2%, P = 0.010). Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that female sex [OR: 1.496, 95% CI (1.075 to 2.083), P = 0.017] and GA > 15.5% [OR: 1.415, 95% CI (1.061 to 1.888), P = 0.018] were independently associated with low responsiveness to clopidogrel.

GA levels and effect on antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel

All patients included in this study were categorized into two groups based on a GA level of 15.5%. The cut-off point was chosen because it may predict the presence of early-phase diabetes [27]. As shown in Table 2, patients with elevated GA levels were more often female and older and were more likely to have diabetes mellitus. These patients had higher baseline fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c levels but lower platelet counts.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of patients by GA categories

| GA ≤ 15.5% (n = 609) | GA > 15.5% (n = 412) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, m (%) | 465 (76.4%) | 287 (69.7%) | 0.017 |

| Age, y | 58.4 ± 10.0 | 63.0 ± 10.1 | 0.000 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.0 ± 3.3 | 25.6 ± 3.1 | 0.126 |

| Medical history, n, (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 73 (12.0%) | 287 (69.7%) | 0.000 |

| Hypertension | 386 (63.4%) | 282 (68.4%) | 0.095 |

| Previous stroke | 62 (10.2%) | 51 (12.4%) | 0.272 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 40 (6.6%) | 37 (9.0%) | 0.152 |

| Previous CABG | 2 (0.3%) | 6 (1.5%) | 0.067 |

| Previous PCI | 50 (8.2%) | 26 (6.3%) | 0.257 |

| Presentations of ACS | 0.319 | ||

| Unstable angina | 555 (91.1%) | 372 (90.3%) | |

| Non-STEMI | 23 (3.8%) | 23 (5.6%) | |

| STEMI | 31 (5.1%) | 17 (4.1%) | |

| Current or previous smoking, n (%) | 339 (55.7%) | 218 (52.9%) | 0.386 |

| Baseline laboratory evaluation | |||

| PLT, × 109/L | 220.8 ± 56.6 | 212.0 ± 60.2 | 0.019 |

| TC, mmol/L | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 0.342 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 0.356 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.875 |

| TGs, mmol/L | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 0.451 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 71.0 ± 14.4 | 70.7 ± 17.2 | 0.734 |

| Glucose indices | |||

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 7.5 ± 2.4 | 0.000 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 1.4 | 0.000 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.1 (1.6–3.1) | 3.3 (1.9–4.9) | 0.000 |

| Antiplatelet responsiveness to clopidogrel | |||

| Responders to clopidogrel | 459 (75.4%) | 273 (66.3%) | 0.002 |

| ADPi | 45.4 ± 25.4 | 39.7 ± 23.8 | 0.000 |

| MAADP | 35.2 ± 14.5 | 39.0 ± 13.9 | 0.000 |

BMI body mass index, CABG coronary artery bypass graft, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, non-STEMI non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, PLT platelet count, TC total cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, TGs triglycerides, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, ADPi ADP-induced platelet inhibition rate, MAADP the maximum amplitude of ADP-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength

There was also a significant interaction between GA level and the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel measured by TEG. Pearson correlation analysis revealed that the GA level was significantly negatively correlated with the ADP-induced platelet inhibition rate (r = − 0.161, P = 0.000) and positively correlated with the value of MAADP (r = 0.191, P = 0.000). Additionally, in patients with a GA level ≤ 15.5%, the ADP-induced platelet inhibition rate was higher, and the value of MAADP was obviously lower (Fig. 1a, b); that is, these patients had a normal response to clopidogrel more often than patients with a GA level > 15.5% (75.4% vs. 66.3%, P = 0.002; Fig. 1c). In this study group, a GA level ≤ 15.5% was associated with a high positive value [75.4%, 95% CI 73.0% to 77.6%] for the prediction of normal responsiveness to clopidogrel and might be a clinical biomarker to guide DAPT de-escalation.

Fig. 1.

a ADP-induced platelet inhibition rate (ADPi) and b the maximum amplitude of ADP-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength (MAADP) in patients with low (≤ 15.5%) and high (> 15.5%) glycated albumin (GA). c Analysis of the frequency of responders to clopidogrel with low/high GA level. Analysis showed patients with a GA level ≤ 15.5% had a normal response to clopidogrel more often than patients with a GA level > 15.5% (P = 0.002)

Discussion

Increased platelet aggregation and activation have been observed in diabetic patients compared with those in nondiabetic patients, and a high proportion of nonresponders to clopidogrel were also observed in the diabetic population [17, 28]. It has also been described that patients with poorly controlled diabetes have greater platelet reactivity and weaker response to clopidogrel [18, 29–31]. In these studies, HbA1c was the most common marker of glycemic control. However, even though an HbA1c level ≥ 6.5% has been recommended as one of the criteria for diagnosing diabetes mellitus [32], the limitations of HbA1c have been widely acknowledged. The use of HbA1c is not recommended in clinical situations that might interfere with the metabolism of hemoglobin, such as in the contexts of hemolytic, secondary or iron-deficiency anemia; hemoglobinopathies; pregnancy; and uremia [32], and HbA1c exhibits a delayed response to changes in treatment since it reflects the effect of long-term control of glycemia. GA is a new measure of glycemia based on the amount of glucose in the serum or plasma attached to albumin rather than to erythrocyte hemoglobin. GA does not require fasting for its measurement and reflects short-term glycemia due to the short half-life of albumin, which is approximately 2–4 weeks [33]. Compared to HbA1c, GA can be used for patients with anemia or hemoglobinopathies and could more accurately reflect the actual status of glycemic control [34].

Association of antiplatelet responsiveness to clopidogrel with GA levels

The main finding of this study is the documented relationship between the GA level on admission and antiplatelet responsiveness in clopidogrel-treated ACS patients according to TEG and LTA. A GA level > 15.5% was an independent risk factor for increased platelet reactivity in the TEG and LTA test performed to assess the response to clopidogrel, and a GA level ≤ 15.5% was associated with a positive predictive value > 70% for the prediction of normal responsiveness to clopidogrel, which might be a clinical biomarker to guide DAPT de-escalation. Previous studies have demonstrated the association between GA and the effect of DAPT on ischemic stroke [25], but to the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined the interaction in ACS patients, in whom the achievement of optimal P2Y12 inhibition is of paramount importance.

Despite the greater efficacy of prasugrel and ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in ischemic benefit after ACS and being recommended by guidelines for these patients [3], clopidogrel is still broadly used. The lower risk for ischemic events beyond the acute phase of ACS, combined with the bleeding risk associated with prolonged potent P2Y2 inhibition, has raised concern about the clinical benefit associated with their chronic use. Therefore, P2Y12 inhibitor de-escalation frequently occurs among patients with ACS in real-world practice, which can be done unguided based on clinical judgment or guided by platelet function testing or CYP2C19 genotyping [13]. However, if clinicians apply platelet function testing to guide de-escalation, they must switch patients from a potent P2Y12 inhibitor to clopidogrel and then wait for clopidogrel to achieve its steady-state effects prior to performing platelet function testing, and if low responsiveness to clopidogrel is confirmed, the therapy with a potent P2Y12 inhibitor needs to be re-instituted [35]. From a more practical clinical viewpoint, measuring blood biomarkers such as GA is less time consuming and less expensive than sequencing variants of cytochrome P450 genes. Moreover, because GA level reflects a shorter-term mean glycemia level (2–4 weeks), it remains stable and is a real marker of the glycemic control several weeks before ACS onset. Therefore, this study suggested an easy-to-implement and economical method to predict a patient’s response to clopidogrel therapy.

Potential underlying mechanisms

Common cardiovascular risk factors, such as age, sex, BMI, smoking status, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and chronic kidney disease, are known to interfere with clopidogrel antiplatelet effects [9, 36]. According to multiple linear regression analysis, we adjusted these factors and found that the independent effect of GA on antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel remained, and this association was independent of history of diabetes mellitus. This result has various explanations. First, GA is characterized by more rapid changes than HbA1c and reflects the change in patients’ acute phase glycemia status prior to ACS onset, regardless of the history of diabetes. Second, GA with loss of fatty-acid-binding capacity could also promote platelet activation and aggregation, which contribute to platelet hyperactivity and increased thrombosis [37–39]. Finally, we used a GA value of 15.5% as the cut-off point, which was the recommended value to predict the presence of early-phase diabetes in an epidemiologic study of an East Asian population [27]. Therefore, the cut-off point we used might identify patients with diabetes at an earlier stage than currently possible. These findings were supported by the findings of a weak association between the GA level and history of diabetes.

Limitations

Several limitations in the present study should be mentioned. This was a single-center study with a relatively small sample size, which may introduce bias into the primary findings. Second, TEG- and LTA-defined low responsiveness to clopidogrel was the primary efficacy outcome rather than clinical follow-up of cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial infarction and stroke. Third, the measurement of the GA level and platelet reactivity was performed only at baseline, and it would be more useful if serial testing were performed, as some studies have indicated that platelet responsiveness can change over time [40, 41]. Future large-scale prospectively designed trials with appropriate clinical follow-up intervals are warranted to verify the effect of GA on antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel in ACS patients.

Conclusion

In the current study, a high GA level was associated with lower responsiveness to clopidogrel in ACS patients, and this relationship was not mediated by a history of diabetes mellitus. Thus, our findings indicated that the GA level is a useful and practical indicator of ACS patients’ responsiveness to clopidogrel and a GA level ≤ 15.5% might be a clinical biomarker to guide DAPT de-escalation.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the ACS patients by responsiveness to clopidogrel assessed by light transmittance aggregometry.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank American Journal Experts (https://www.aje.com/) for providing English language editing services.

Abbreviations

- GA

Glycated albumin

- ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

- TEG

Thromboelastography

- LTA

Light transmittance aggregometry

- ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

- DAPT

Dual antiplatelet therapy

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- MAADP

The maximum amplitude of ADP-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength

- BMI

Body mass index

- UA

Unstable angina

- Non-STEMI

Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- TC

Total cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- TGs

Triglycerides

- ARBs

Angiotensin receptor blockers

- ACEIs

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- CCBs

Calcium channel blocking agents

- PPIs

Proton pump inhibitors

- OR

Odds ratio

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass graft

- PLT

Platelet count

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance

Authors’ contributions

XLZ, YZ and YCY designed the study. XLZ, QL and CCT contributed to data acquisition. XLZ and QL performed the statistical analysis. XLZ, QL, CCT, YZ and YCY contributed to the discussion. XLZ drafted the manuscript. YCY edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Capital Medical University (Code: 1200020109).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 2018075X) of Beijing Anzhen Hospital and was conducted according to the guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent for participation in the present study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12933-020-01146-w.

References

- 1.Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA, Granger CB, Lange RA, Mack MJ, Mauri L, Mehran R, Mukherjee D, Newby LK, O'Gara PT, Sabatine MS, Smith PK, Smith SC., Jr 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1082–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Costa F, Jeppsson A, Juni P, Kastrati A, Kolh P, Mauri L, Montalescot G, Neumann FJ, Petricevic M, Roffi M, Steg PG, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Levine GN. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:213–260. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Falk V, Head SJ, Juni P, Kastrati A, Koller A, Kristensen SD, Niebauer J, Richter DJ, Seferovic PM, Sibbing D, Stefanini GG, Windecker S, Yadav R, Zembala MO, Group ESCSD 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misumida N, Aoi S, Kim SM, Ziada KM, Abdel-Latif A. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in East Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2018;19:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarese EP, Khan SU, Kołodziejczak M, Kubica J, Buccheri S, Cannon CP, Gurbel PA, De Servi S, Budaj A, Bartorelli A, Trabattoni D, Ohman EM, Wallentin L, Roe MT, James S. Comparative efficacy and safety of oral P2Y(12) inhibitors in acute coronary syndrome: network meta-analysis of 52 816 patients from 12 randomized trials. Circulation. 2020;142:150–160. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li XY, Su GH, Wang GX, Hu HY, Fan CJ. Switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing successful percutaneous coronary intervention in real-world China: occurrences, reasons, and long-term clinical outcomes. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:1446–1454. doi: 10.1002/clc.23074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angiolillo DJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Bernardo E, Alfonso F, Macaya C, Bass TA, Costa MA. Variability in individual responsiveness to clopidogrel: clinical implications, management, and future perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1505–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochholzer W, Trenk D, Fromm MF, Valina CM, Stratz C, Bestehorn HP, Buttner HJ, Neumann FJ. Impact of cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-function polymorphism and of major demographic characteristics on residual platelet function after loading and maintenance treatment with clopidogrel in patients undergoing elective coronary stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2427–2434. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angiolillo DJ, Capodanno D, Danchin N, Simon T, Bergmeijer TO, Ten Berg JM, Sibbing D, Price MJ. Derivation, validation, and prognostic utility of a prediction rule for nonresponse to clopidogrel: the ABCD-GENE score. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.01.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, Rinaldi MJ, Neumann FJ, Metzger DC, Henry TD, Cox DA, Duffy PL, Mazzaferri E, Gurbel PA, Xu K, Parise H, Kirtane AJ, Brodie BR, Mehran R, Stuckey TD. Platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes after coronary artery implantation of drug-eluting stents (ADAPT-DES): a prospective multicentre registry study. Lancet. 2013;382:614–623. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tantry US, Bonello L, Aradi D, Price MJ, Jeong YH, Angiolillo DJ, Stone GW, Curzen N, Geisler T, Ten Berg J, Kirtane A, Siller-Matula J, Mahla E, Becker RC, Bhatt DL, Waksman R, Rao SV, Alexopoulos D, Marcucci R, Reny JL, Trenk D, Sibbing D, Gurbel PA. Consensus and update on the definition of on-treatment platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate associated with ischemia and bleeding. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2261–2273. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angiolillo DJ, Rollini F, Storey RF, Bhatt DL, James S, Schneider DJ, Sibbing D, So DYF, Trenk D, Alexopoulos D, Gurbel PA, Hochholzer W, De Luca L, Bonello L, Aradi D, Cuisset T, Tantry US, Wang TY, Valgimigli M, Waksman R, Mehran R, Montalescot G, Franchi F, Price MJ. International expert consensus on switching platelet P2Y(12) receptor-inhibiting therapies. Circulation. 2017;136:1955–1975. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, Dendale P, Dorobantu M, Edvardsen T, Folliguet T, Gale CP, Gilard M, Jobs A, Jüni P, Lambrinou E, Lewis BS, Mehilli J, Meliga E, Merkely B, Mueller C, Roffi M, Rutten FH, Sibbing D, Siontis GCM. ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angiolillo DJ, Bernardo E, Sabate M, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Costa MA, Palazuelos J, Hernandez-Antolin R, Moreno R, Escaned J, Alfonso F, Banuelos C, Guzman LA, Bass TA, Macaya C, Fernandez-Ortiz A. Impact of platelet reactivity on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1541–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angiolillo DJ, Jakubowski JA, Ferreiro JL, Tello-Montoliu A, Rollini F, Franchi F, Ueno M, Darlington A, Desai B, Moser BA, Sugidachi A, Guzman LA, Bass TA. Impaired responsiveness to the platelet P2Y12 receptor antagonist clopidogrel in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1005–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangiacapra F, Peace AJ, Wijns W, Barbato E. Lack of correlation between platelet reactivity and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients treated with aspirin and clopidogrel. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;32:54–58. doi: 10.1007/s11239-010-0547-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morel O, El Ghannudi S, Hess S, Reydel A, Crimizade U, Jesel L, Radulescu B, Wiesel ML, Gachet C, Ohlmann P. The extent of P2Y12 inhibition by clopidogrel in diabetes mellitus patients with acute coronary syndrome is not related to glycaemic control: roles of white blood cell count and body weight. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:338–348. doi: 10.1160/TH11-12-0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoos MM, Dangas GD, Mehran R, Kirtane AJ, Yu J, Litherland C, Clemmensen P, Stuckey TD, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, Rinaldi MJ, Neumann FJ, Metzger DC, Henry TD, Cox DA, Duffy PL, Brodie BR, Mazzaferri EL, Jr, Maehara A, Stone GW. Impact of Hemoglobin A1c levels on residual platelet reactivity and outcomes after insertion of coronary drug-eluting stents (from the ADAPT-DES study) Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selvin E, Rawlings AM, Grams M, Klein R, Sharrett AR, Steffes M, Coresh J. Fructosamine and glycated albumin for risk stratification and prediction of incident diabetes and microvascular complications: a prospective cohort analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:279–288. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70199-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang YD, Wang W, Yang M, Zhang K, Chen J, Qiao S, Yan H, Wu Y, Huang X, Xu B, Gao R, Yang Y, Investigators C. Randomized comparisons of double-dose clopidogrel or adjunctive cilostazol versus standard dual antiplatelet in patients with high posttreatment platelet reactivity: results of the CREATIVE trial. Circulation. 2018;137:2231–2245. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bliden KP, DiChiara J, Tantry US, Bassi AK, Chaganti SK, Gurbel PA. Increased risk in patients with high platelet aggregation receiving chronic clopidogrel therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: is the current antiplatelet therapy adequate? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Guyer K, Cho PW, Zaman KA, Kreutz RP, Bassi AK, Tantry US. Platelet reactivity in patients and recurrent events post-stenting: results of the PREPARE POST-STENTING study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1820–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Navickas IA, Mahla E, Dichiara J, Suarez TA, Antonino MJ, Tantry US, Cohen E. Adenosine diphosphate-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength: a new thrombelastographic indicator of long-term poststenting ischemic events. Am Heart J. 2010;160:346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q, Li M, Yu X, He J, Gao Y, Zhang X, Wu C, Luo Y, Zhang Y, Ren X. Impact of mean platelet aggregation degree on long-term clinical outcomes among patients undergoing a complex percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis. 2017;28:478–485. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Wang Y, Wang D, Lin J, Wang A, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang C, Wang Y. Glycated albumin predicts the effect of dual and single antiplatelet therapy on recurrent stroke. Neurology. 2015;84:1330–1336. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price MJ, Berger PB, Teirstein PS, Tanguay JF, Angiolillo DJ, Spriggs D, Puri S, Robbins M, Garratt KN, Bertrand OF, Stillabower ME, Aragon JR, Kandzari DE, Stinis CT, Lee MS, Manoukian SV, Cannon CP, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Standard- vs high-dose clopidogrel based on platelet function testing after percutaneous coronary intervention: the GRAVITAS randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;305:1097–1105. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furusyo N, Koga T, Ai M, Otokozawa S, Kohzuma T, Ikezaki H, Schaefer EJ, Hayashi J. Utility of glycated albumin for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in a Japanese population study: results from the Kyushu and Okinawa Population Study (KOPS) Diabetologia. 2011;54:3028–3036. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angiolillo DJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Bernardo E, Ramirez C, Sabate M, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Hernandez R, Moreno R, Escaned J, Alfonso F, Banuelos C, Costa MA, Bass TA, Macaya C. Platelet function profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease on combined aspirin and clopidogrel treatment. Diabetes. 2005;54:2430–2435. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singla A, Antonino MJ, Bliden KP, Tantry US, Gurbel PA. The relation between platelet reactivity and glycemic control in diabetic patients with cardiovascular disease on maintenance aspirin and clopidogrel therapy. Am Heart J. 2009;158(784):e781–786. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuliczkowski W, Gasior M, Pres D, Kaczmarski J, Greif M, Laszewska A, Szewczyk M, Hawranek M, Tajstra M, Zeglen S, Polonski L, Serebruany V. Effect of glycemic control on response to antiplatelet therapy in patients with diabetes mellitus and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nusca A, Tuccinardi D, Proscia C, Melfi R, Manfrini S, Nicolucci A, Ceriello A, Pozzilli P, Ussia GP, Grigioni F, Di Sciascio G. Incremental role of glycaemic variability over HbA1c in identifying type 2 diabetic patients with high platelet reactivity undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18:147. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0952-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Diabetes A 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:S14–S31. doi: 10.2337/dc20-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freitas PAC, Ehlert LR, Camargo JL. Glycated albumin: a potential biomarker in diabetes. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2017;61:296–304. doi: 10.1590/2359-3997000000272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koga M. Glycated albumin; clinical usefulness. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;433:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angiolillo DJ. Dual antiplatelet therapy guided by platelet function testing. Lancet. 2017;390:1718–1720. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karazniewicz-Lada M, Danielak D, Glowka F. Genetic and non-genetic factors affecting the response to clopidogrel therapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:663–683. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.666524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubenstein DA, Yin W. Glycated albumin modulates platelet susceptibility to flow induced activation and aggregation. Platelets. 2009;20:206–215. doi: 10.1080/09537100902795492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blache D, Bourdon E, Salloignon P, Lucchi G, Ducoroy P, Petit JM, Verges B, Lagrost L. Glycated albumin with loss of fatty acid binding capacity contributes to enhanced arachidonate oxygenation and platelet hyperactivity: relevance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64:960–972. doi: 10.2337/db14-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soaita I, Yin W, Rubenstein DA. Glycated albumin modifies platelet adhesion and aggregation responses. Platelets. 2017;28:682–690. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2016.1260703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price MJ, Angiolillo DJ, Teirstein PS, Lillie E, Manoukian SV, Berger PB, Tanguay JF, Cannon CP, Topol EJ. Platelet reactivity and cardiovascular outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: a time-dependent analysis of the Gauging responsiveness with a VerifyNow P2Y12 assay: impact on thrombosis and safety (GRAVITAS) trial. Circulation. 2011;124:1132–1137. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaitner J, Stegherr J, Morath T, Braun S, Bernlochner I, Schomig A, Kastrati A, Sibbing D. Stability of the high on-treatment platelet reactivity phenotype over time in clopidogrel-treated patients. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:107–112. doi: 10.1160/TH10-07-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the ACS patients by responsiveness to clopidogrel assessed by light transmittance aggregometry.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.