Abstract

Perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas (PMAVFs) are uncommon vascular malformations, and they rarely occur at the level of the craniovertebral junction (CVJ). The therapeutic management is challenging and can include observation alone, endovascular occlusion, or surgical exclusion, depending on both patient and malformation characteristics. A systematic literature search was conducted using MEDLINE, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases, searching for the following combined MeSH terms: (perimedullary arteriovenous fistula OR dural arteriovenous shunt) AND (craniocervical junction OR craniovertebral junction). We also present an emblematic case of PMAVF at the level of the craniovertebral junction associated to a venous pseudoaneurysm. A total of 31 published studies were identified; 10 were rejected from our review because they did not match our inclusion criteria. Our case was not included in the systematic review. We selected 21 studies for this systematic review with a total of 58 patients, including 20 females (34.5%) and 38 males (65.5%), with a female/male ratio of 1:1.9. Thirty-nine out of 58 patients underwent surgical treatment (67.2%), 15 out of 58 patients were treated with endovascular approach (25.8%), 3 out of 58 patients underwent combined treatment (5.2%), and only 1 patient was managed conservatively (1.7%). An improved outcome was reported in 94.8% of cases (55 out of 58 patients), whereas 3 out of 58 patients (5.2%) were moderately disabled after surgery and endovascular treatment. In literature, hemorrhagic presentation is reported as the most common onset (subarachnoid hemorrhage in 63% and intramedullary hemorrhage in 10%), frequently caused either by venous dilation, due to an ascending drainage pathway into an intracranial vein, or by the higher venous flow rates that can be associated with intracranial drainage. Hiramatsu and Sato stated that arterial feeders from the anterior spinal artery (ASA) and aneurysmal dilations are associated with hemorrhagic presentation. In agreement with the classification by Hiramatsu, we defined the PMAVF of the CVJ as a vascular lesion fed by the radiculomeningeal arteries from the vertebral artery and the spinal pial arteries from the ASA and/or lateral spinal artery. Considering the anatomical characteristics, we referred to our patient as affected by PMAVF, even if it was difficult to precisely localize the arteriovenous shunts because of the complex angioarchitecture of the fine feeding arteries and draining veins, but we presumed that the shunt was located in the point of major difference in vessel size between the feeding arteries and draining veins. PMAVFs of CVJ are rare pathologies of challenging management. The best diagnostic workup and treatment are still controversial: more studies are needed to compare different therapeutic strategies concerning both long-term occlusion rates and outcomes.

Keywords: Aneurysm, angiography, arteriovenous fistula, craniovertebral junction, perimedullary, subarachnoid hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

Perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas (PMAVFs) of the craniovertebral junction (CVJ) represent <1% of all cranial or spinal arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs)[1,2,3] and are classified as type 5 AVFs according to Hiramatsu et al.[4] PMAVFs may present clinically either with acute neurological deficits due to subarachnoid or intramedullary hemorrhage, or with progressive myelopathy caused by venous congestion;[5,6] a differential diagnosis must be made with spinal thoracolumbar AVFs, whose main presentation is myelopathy.[7,8] Therapeutic management includes options such as observation alone, endovascular occlusion, surgical exclusion, or a combination of these two last techniques, depending on patient-specific and lesion-specific characteristics. Observation carries the risk of rebleeding, surgical treatment presents challenges related to the operative approach, and endovascular treatment presents several technical limitations due to vessels’ size and risk of medullary ischemia. We present a rare case of a patient affected by ruptured PMAVF of CVJ associated to a venous pseudoaneurysm, providing new insights into the diagnosis and management of this rare entity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study selection

A systematic review of the literature was conducted using MEDLINE, Cochrane, and EBSCO databases using the following combined MeSH terms: (perimedullary arteriovenous fistula OR dural arteriovenous shunt) and (craniocervical junction OR craniovertebral junction). This search was limited to studies published in English. The PRISMA flow diagram of our search is available in Figure 1. Eligibility criteria were limited by the nature of the existing literature on PMAVFs, which consists of case series, case reports, and only one multicentric study. A definition of PMAVF has been reported only in 2017;[3] all previous papers were meticulously analyzed to define the anatomical features of every AVF. All papers reporting PMAVFs not located at the CVJ were not included in this review. The reference list of all the articles included in this review was examined searching for additional papers.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram reports the decision algorithm for the selection of the studies of the systematic review

Data extraction

All included papers were meticulously reviewed and analyzed for their study design, methodology, and patient characteristics. All patients’ data were recorded when available, including age, sex, clinical presentation, interval between onset of symptoms and diagnosis, treatment options (surgery or endovascular), and outcome.

Descriptive statistics are reported, including means and proportions. No formal statistical comparisons were performed due to small sample size and insufficient power to detect differences between groups.

RESULTS

A total of 31 published studies from 1996 to 2019 were identified through our search and additional reference evaluation. After detailed examination, ten were rejected from our review, as they were written in other languages or AVFs were not at the level of the CVJ. Our case was not included in the systematic review. Patients data are reported in Table 1.[4,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] We selected 21 studies for this systematic review, with a total of 58 patients, including 20 females (34.5%) and 38 males (65.5%), with a female/male ratio of 1:1.9. Patients presented a mean age of 55.9 years, ranging from 38 to 82 years. The presentation with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) occurred in 45 out of 58 patients (77.6%), whereas 11 out of 58 patients (18.9%) presented with sensory and/or motor dysfunction; 2 out of 58 cases (3.4%) were incidental findings. In 35 out of 58 patients (60.3%), the onset was acute. In 9 out of 58 patients (15.5%), the mean interval between the presentation of symptoms and diagnosis was 12.3 months, ranging between 0.5 and 48 months; in 13 out of 58 patients (22.4%), this time interval was not reported. Thirty-nine out of 58 patients underwent surgical treatment (67.2%), whereas 15 out of 58 patients were treated with the endovascular procedure only (25.8%); 3 out of 58 patients were treated with combined surgical and endovascular approach (5.2%); only one patient was managed conservatively (1.7%). An improved outcome was reported in 94.8% of cases (55 out of 58 patients), whereas 3 out of 58 patients (5.2%) were moderately disabled after treatment.

Table 1.

Systematic review of demographic, symptoms, interval time to diagnosis, treatment, and outcome data of patients affected by perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas of the craniovertebral junction reported in the literature to date

| Authors and year | Number of patients | Age (years) | Sex | Symptoms | Time to diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hiramatsu et al. 2018[4] | 6 | Mean 67 | 4 males, 2 females | SAH symptoms | Not reported | 4 endovascular treatments, 2 surgeries | Improved |

| Mascalchi et al. 1996[9] | 2 | 69, 53 | Male | Lower limb paresthesias, urinary retention, progressive gait disturbance | 4 years, 2 years | Surgery (clipped and excised); endovascular treatment (injection of glue) | Both improved |

| Kinouchi et al. 1998[10] | 10 | 63, 65, 44, 52, 70, 68, 50, 61, 60, 45 | 7 males, 3 females | 2 incidental, 1 back pain, bowel and bladder disturbance, sensory disturbances, trigeminal nerve disturbance, quadriparesis, and respiratory disturbance, 7 SAH symptoms | Not reported, 1 year, 7 acute onset | Surgery | Improved |

| Kuwayama et al. 1999[11] | 3 | 73, 52, 52 | 2 males, 1 female | SAH symptoms | Acute onset | 1 conservative, 1 endovascular treatment, 1 surgery | Moderately disabled |

| Yoshida et al. 1999[12] | 1 | 68 | Male | Lower limb motor and sensory disturbances | 6 months | Surgery | Improved |

| Asakawa et al. 2002[13] | 1 | 64 | Male | Lower limb weakness, dyspnea | 2 weeks | Embolization + surgical exclusion | Improved |

| Lv et al. 2011[14] | 4 | 73, 66, 51, 40 | 3 males, 1 female | SAH symptoms | Acute onset | Endovascular treatment | Improved |

| Ohba et al. 2011[15] | 1 | 55 | Male | SAH symptoms | Acute onset | Surgery | Improved |

| Kulwin et al. 2012[16] | 2 | 44, 54 | Female | Altered mental status, right hemiparesis; left hemiparesis and diplopia | Acute onset | Surgery | Improved |

| Sato et al. 2013[17] | 9 | 59, 82, 78, 62, 64, 62, 60, 64, 66 | 5 males, 4 females | SAH symptoms | Acute onset | Surgery | Improved |

| Gilard et al. 2013[18] | 1 | 59 | Female | SAH symptoms | Acute onset | Surgery | Improved |

| Kasliwal et al. 2015[19] | 1 | 59 | Female | SAH symptoms | Acute onset | Surgery | Improved |

| Jeon et al. 2015[20] | 1 | 73 | Male | Progressive weakness of both lower extremities | 10 months | Endovascular treatment+surgery | Improved |

| Pop et al. 2015[21] | 1 | 38 | Male | Paraparesis and acute urinary retention, generalized tonic-clonic seizures | 28 days | Endovascular treatment | Improved |

| Ogita et al. 2016[22] | 1 | 58 | Male | SAH symptoms | 9 months | Surgery | Improved |

| Kawasaki et al. 2016[23] | 1 | 73 | Female | Headache and left hemiparesis | Acute onset | Conservative | Improved |

| Enokizono et al. 2017[24] | 1 | 50 | Female | Neck pain and urination difficulty, paralysis, and numbness of all four extremities | 1 month | Clipping | Improved |

| Fujimoto et al. 2018[25] | 6 | 69, 79, 76, 64, 68, 46 | 4 males, 2 females | SAH symptoms | Not reported | 5 surgeries, 1 endovascular treatment | Improved |

| Kanemaru et al. 2019[26] | 4 | 67, 76, 45, 53 | 3 males, 1 female | SAH symptoms | Acute onset | Surgery | Improved |

| Sato et al. 2019[27] | 1 | 69 | Male | SAH symptoms | Acute onset | Endovascular treatment + surgery | Improved |

| Yoshida et al. 2019[28] | 1 | 65 | Male | SAH symptoms | Acute onset | Endovascular treatment | Improved |

SAH - Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Case presentation

Medical history and clinical examination

A 73-year-old woman with a history of osteoporosis presented to our institution with sudden headache, vomiting, and rigor nucalis associated to dysesthesia of the upper limbs.

Imaging

Brain angio-computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated diffuse SAH (Fisher grade 3) [Figure 2], as well as magnetic resonance angiography revealed the presence of a PMAVF associated to a venous pseudoaneurysm at C1–C2 level [Figure 3]. Subsequent digital subtraction angiography (DSA) confirmed a PMAVF of the CVJ, responsible for the recent SAH; the PMAVF was located in the right paramedian position, posterior to the middle third of the odontoid process with caudal extension up to C2–C3, with maximum dimensions on the sagittal plane of about 1.2 cm [Figure 4]. Cranially to the PMAVF, there was evidence of venous pseudoaneurysm. The PMAVF had arterial feeders from both hypertrophic anterior spinal arteries, originating from the intracranial portion and from cervical radicular branches – which stemmed at the right C3–C4 and left C2 level, of greater caliber and flow to the left – of both vertebral arteries (VAs); the main venous drainage, dilated, was at the level of the basal venous plexus, with drainage in both inferior petrous sinuses and at the level of the left posterior cervical paravertebral plexus, also markedly dilated.

Figure 2.

Brain computed tomography scan demonstrated diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage (Fisher grade 3) (left) and computed tomography angiography documented the presence of a vascular malformation of the craniovertebral junction (right)

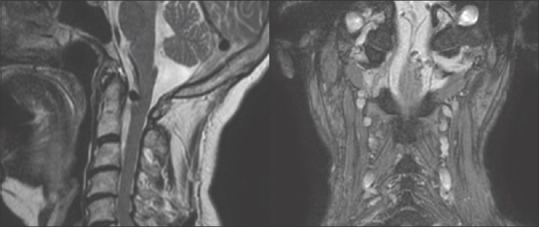

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance angiography revealed the presence of a perimedullary arteriovenous fistula associated to a venous pseudoaneurysm at C1–C2 level

Figure 4.

DSA showing craniovertebral junction perimedullary arteriovenous fistula. Cranially to the perimedullary arteriovenous fistula, there was evidence of venous pseudoaneurysm; the perimedullary arteriovenous fistula had arterial feeders from both hypertrophic anterior spinal arteries, originating from the intracranial portion and from cervical radicular branches – which stemmed at the right C3–C4 and left C2 level, of greater caliber and flow to the left – of both vertebral arteries; the main venous drainage, dilated, was at the level of the basal venous plexus, with drainage in both inferior petrous sinuses and at the level of the left posterior cervical paravertebral plexus, also markedly dilated

Management

After a multidisciplinary discussion, we decided to perform surgical treatment of the PMAVF because no navigable afferent vessels allowed the exclusion of the shunt point during the endovascular procedure. However, the patient refused the treatment, probably due both to progressive clinical improvement and to the high surgical risks explained during informed consent. She improved to complete recovery, CT scan revealing progressive reabsorption of the SAH. After 9-month follow-up, the PMAVF is stable in seriated DSA and angio-CT scans, and the patient is in good clinical conditions.

DISCUSSION

Historically, PMAVFs were considered congenital.[17] Anteriorly located shunts represent an atypical feature.[29] PMAVFs present direct shunts between the vessels at the level of the pia mater, superficially to the spinal cord, and they can be located anteriorly or anterolaterally to the spinal cord.[15,30,29] Lawton et al.[31] suggested that angiogenesis could be induced by venous hypertension, responsible for the development of AVFs in experimental models. Sato et al.[17] hypothesized that venous hypertension can cause venous hypoxia, which induces additional pial shunts in patients with AVFs of the craniovertebral junction. According to Hassler et al.,[32] venous drainage close to the nerve root sleeve could worsen a sump effect. Moreover, blood supply to the radiculomedullary arteries may be near the origin of the venous drainage.[15,33] In literature, hemorrhagic presentation is reported as the most common onset (SAH in 63% and intramedullary hemorrhage in 10%),[1,6,34] frequently caused either by venous dilation, due to an ascending drainage pathway into an intracranial vein,[6,10,35,36,37] or by the higher venous flow rates that can be associated with intracranial drainage.[10,38] For Hiramatsu et al.[3] and Sato et al.,[17] arterial feeders from the anterior spinal artery (ASA) and aneurysmal dilations are associated with hemorrhagic presentation.[1,17] However, there is controversy about the definition of PMAVFs of the CVJ because of the angiographic complexity of these lesions. In agreement with the classification by Hiramatsu et al.,[3] we defined the PMAVF of the CVJ as a vascular lesion fed by the radiculomeningeal arteries from the VA and the spinal pial arteries from the ASA and/or lateral spinal artery. These AVFs are direct arteriovenous shunts that link both radiculomeningeal and pial feeders with the intramural or epidural vein at the same fistulous point. Considering the anatomical characteristics, we referred to our patient as affected by PMAVF, even if it was difficult to precisely localize the arteriovenous shunts because of the complex angioarchitecture of the fine feeding arteries and draining veins, but we presumed that the shunt was located in the point of major difference in vessel size between the feeding arteries and draining veins. PMAVFs are characterized by small, tortuous feeding arteries and arteries originating from the VA, which may present an acute angle that can be technically challenging for endovascular treatment.[17,39] A safer treatment is represented by surgical disconnection by clipping and/or coagulating the fistula, in cases with a small shunt fistula, small tortuous feeding arteries, or a dominant pial arteriovenous shunt. Based on the reported case, also conservative treatment can play a role and could be reserved to elderly and/or fragile patients. Therefore, a careful endovascular examination is mandatory for accurate diagnosis and proper treatment of patients suspected of having a PMAVF of the CVJ.

CONCLUSIONS

We presented one emblematic patient, affected by rare PMAVF of the CVJ that refused treatment, but serial radiological follow-up demonstrated the stability of the lesion with good clinical performance. Thus, the present paper focused on a peculiar subtype of AVF of the CVJ that presented controversies both for radiological diagnosis and treatment indications. Therefore, we suggest a combined endovascular and neurosurgical approach to treat this type of patients, as it is possible to obtain the best postoperative outcome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuwayama N, Endo S, Kubo M, Sakai N. Present status in the treatment of dural arteriovenous fistulas in Japan. Jpn J Neurosurg (Tokyo) 2011;20:12–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinges MH, Thron A, Mull M, Huffmann BC, Gilsbach JM. Dural arteriovenous fistulae at the foramen magnum. J Neurol. 2001;248:197–203. doi: 10.1007/s004150170226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiramatsu M, Sugiu K, Ishiguro T, Kiyosue H, Sato K, Takai K, et al. Angioarchitecture of arteriovenous fistulas at the craniocervical junction: A multicenter cohort study of 54 patients. J Neurosurg. 2018;128:1839–49. doi: 10.3171/2017.3.JNS163048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiramatsu M, Sugiu K, Ishiguro T, Kiyosue H, Sato K, Takai K, et al. Angioarchitecture of arteriovenous fistulas at the craniovertebral junction: A multicenter cohort study of 54 patients. J Neurosurg. 2018;128:1839–49. doi: 10.3171/2017.3.JNS163048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endo T, Shimizu H, Sato K, Niizuma K, Kondo R, Matsumoto Y, et al. Cervical perimedullary arteriovenous shunts: A study of 22 consecutive cases with a focus on angioarchitecture and surgical approaches. Neurosurgery. 2014;75:238–49. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang JY, Molenda J, Bydon A, Colby GP, Coon AL, Tamargo RJ, et al. Natural history and treatment of craniovertebral junction dural arteriovenous fistulas. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1701–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klopper HB, Surdell DL, Thorell WE. Type I spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas: Historical review and illustrative case. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26:E3. doi: 10.3171/FOC.2009.26.1.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krings T, Geibprasert S. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:639–48. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mascalchi M, Scazzeri F, Prosetti D, Ferrito G, Salvi F, Quilici N. Dural arteriovenous fistula at the craniocervical junction with perimedullary venous drainage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:1137–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinouchi H, Mizoi K, Takahashi A, Nagamine Y, Koshu K, Yoshimoto T. Dural arteriovenous shunts at the craniocervical junction. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:755–61. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.5.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuwayama N, Kubo M, Nishijima M, Horie Y, Endo S, Takaku A. Treatment of intracranial (dural) arteriovenous fistulas in unusual locations. Interv Neuroradiol. 1999;5(1):115–20. doi: 10.1177/15910199990050S121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida S, Oda Y, Kawakami Y, Sato S. Progressive myelopathy caused by dural arteriovenous fistula at the craniocervical junction—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1999;39:376–9. doi: 10.2176/nmc.39.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asakawa H, Yanaka K, Fujita K, Marushima A, Anno I, Nose T. Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula showing diffuse MR enhancement of the spinal cord: Case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2002;58:251–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(02)00861-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lv X, Yang X, Li Y, Jiang C, Wu Z. Dural arteriovenous fistula with spinal perimedullary venous drainage. Neurol India. 2011;59:899–902. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.91374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohba S, Onozuka S, Horiguchi T, Kawase T, Yoshida K. Perimedullary arteriovenous fistula at the craniocervical junction-Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2011;51:299–301. doi: 10.2176/nmc.51.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulwin C, Bohnstedt BN, Scott JA, Cohen-Gadol A. Dural arteriovenous fistulas presenting with brainstem dysfunction: Diagnosis and surgical treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2012;32:E10. doi: 10.3171/2012.2.FOCUS1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato K, Endo T, Niizuma K, Fujimura M, Inoue T, Shimizu H, et al. Concurrent dural and perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas at the craniocervical junction: Case series with special reference to angioarchitecture. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:451–9. doi: 10.3171/2012.10.JNS121028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilard V, Curey S, Tollard E, Proust F. Coincidental vascular anomalies at the foramen magnum: Dural arteriovenous fistula and high flow aneurysm on perimedullary fistula. Neurochirurgie. 2013;59:210–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasliwal MK, Moftakhar R, O’Toole JE, Lopes DK. High cervical spinal subdural hemorrhage as a harbinger of craniocervical arteriovenous fistula: An unusual clinical presentation. Spine J. 2015;15:e13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeon JP, Cho YD, Kim CH, Han MH. Complex spinal arteriovenous fistula of the craniocervical junction with pial and dural shunts combined with contralateral dural arteriovenous fistula. Interv Neuroradiol. 2015;21:733–7. doi: 10.1177/1591019915609128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pop R, Manisor M, Aloraini Z, Chibarro S, Proust F, Quenardelle V, et al. Foramen magnum dural arteriovenous fistula presenting with epilepsy. Interv Neuroradiol. 2015;21:724–7. doi: 10.1177/1591019915609783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogita S, Endo T, Inoue T, Sato K, Endo H, Tominaga T. Traumatic spinal perimedullary arteriovenous fistula induced by a cervical glass stab injury. World Neurosurg. 2016;96:610–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.09.024. 610.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawasaki T, Fukuda H, Kurosaki Y, Handa A, Chin M, Yamagata S. Acute compressive myelopathy caused by spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A combined effect of asymptomatic cervical spondylosis. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:619e1–000. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enokizono M, Sato N, Morikawa M, Kimura Y, Sugiyama A, Maekawa T, et al. “Black butterfly” sign on T2*-weighted and susceptibility-weighted imaging: A novel finding of chronic venous congestion of the brain stem and spinal cord associated with dural arteriovenous fistulas. J Neurol Sci. 2017;379:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimoto S, Takai K, Nakatomi H, Kin T, Saito N. Three-dimensional angioarchitecture and microsurgical treatment of arteriovenous fistulas at the craniocervical junction. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;53:140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanemaru K, Yoshioka H, Hashimoto K, Murayama H, Ogiwara M, Yagi T, et al. Efficacy of intraarterial fluorescence video angiography in surgery for dural and perimedullary arteriovenous fistula at craniocervical junction. World Neurosurg. 2019;126:e573–e579. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato H, Wada H, Noro S, Saga T, Kamada K. Subarachnoid hemorrhage with concurrent dural and perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas at craniocervical junction: Case report and literature review. World Neurosurg. 2019;127:331–4. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida K, Sato S, Inoue T, Ryu B, Shima S, Mochizuki T, et al. Transvenous embolization for craniocervical junction epidural arteriovenous fistula with a pial feeder aneurysm. Interv Neuroradiol. 2020;26:170–7. doi: 10.1177/1591019919874571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onda K, Yoshida Y, Watanabe K, Arai H, Okada H, Terada T. High cervical arteriovenous fistulas fed by dural and spinal arteries and draining into a single medullary vein: Report of 3 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20:256–64. doi: 10.3171/2013.11.SPINE13402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen HT, Rhoton AL, Jr, Katsuta T, de Oliveira E. Microsurgical anatomy of the transcondylar, supracondylar, and paracondylar extensions of the far-lateral approach. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:555–85. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.4.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawton MT, Jacobowitz R, Spetzler RF. Redefined role of angiogenesis in the pathogenesis of dural arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:267–74. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.2.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassler W, Thron A, Grote EH. Hemodynamics of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas. An intraoperative study. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:360–70. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.3.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Monaco R, Rodesch G, Terbrugge K, Burrows P, Lasjaunias P. Multifocal dural arteriovenous shunts in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 1991;7:425–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00263183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takai K, Kin T, Oyama H, Iijima A, Shojima M, Nishido H, et al. The use of 3D computer graphics in the diagnosis and treatment of spinal vascular malformations. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;15:654–9. doi: 10.3171/2011.8.SPINE11155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aviv RI, Shad A, Tomlinson G, Niemann D, Teddy PJ, Molyneux AJ, et al. Cervical dural arteriovenous fistulae manifesting as subarachnoid hemorrhage: Report of two cases and literature review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:854–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kai Y, Hamada J, Morioka M, Yano S, Mizuno T, Kuratsu J. Arteriovenous fistulas at the cervicomedullary junction presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage: Six case reports with special reference to the angiographic pattern of venous drainage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1949–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao J, Xu F, Ren J, Manjila S, Bambakidis NC. Dural arteriovenous fistulas at the craniovertebral junction: A systematic review. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8:684–3. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-011775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim DJ, Willinsky R, Geibprasert S, Krings T, Wallace C, Gentili F, et al. Angiographic characteristics and treatment of cervical spinal dural arteriovenous shunts. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1512–15. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitsuhashi Y, Aurboonyawat T, Pereira VM, Geibprasert S, Toulgoat F, Ozanne A, et al. Dural arteriovenous fistulas draining into the petrosal vein or bridging vein of the medulla: Possible homologs of spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:889–99. doi: 10.3171/2009.1.JNS08840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]