Abstract

Introduction and Objectives:

Buccal mucosal graft (BMG) is frequently used for the reconstruction of urethral strictures with acceptable donor-site morbidity after graft harvest. There are only a few prospectively designed studies with a small number of patients reporting oral complications, particularly the mouth opening in the long terms. We did an objective assessment of mouth opening before and after 6 months of BMG urethroplasty as well as pain scores.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty-eight patients who underwent BMG urethroplasty were included in the study between May 2013 and December 2014. Preoperative mouth opening (reference point between two incisors with the highest of three readings taken as final) was measured using a Vernier caliper. Harvest site was left open to heal by secondary intentions. Postoperatively, mouth opening and pain scores using self-administered (Visual Analog Scale [VAS]) assessed on day 1 and day 3, and follow-up at 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months. Data were analyzed as mean (standard deviation [SD]), proportion, and median (inter-quartile range [IQR]) with two-tailedP < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results:

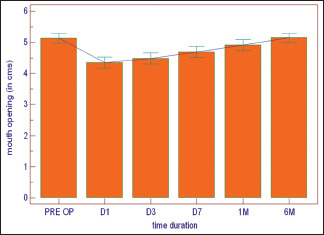

The mean age was 39.6 years. The graft was harvested from a single cheek in 50% of patients. In remaining, it was taken from both cheeks, both cheeks with lip, and both cheeks with the tongue in 29.31%, 17.24%, and 3.5%, of patients, respectively. Preoperative mouth opening (5.13 cm [0.08]) was statistically significantly more than mouth opening on day 1 (4.34 cm [0.09]), day 3 (4.48 [0.09]), and day 7 (4.69 cm [0.09]). Mean difference became insignificant at the interval of 1 month (4.91 cm [0.09]) with 6 months’ values showing marginal improvement over preoperative values (5.14 cm [0.07]). Pain was tolerable and patients reported low median VAS 2 (2–4) on day 1 and day 3 each. Reported median VAS became 0 (0–0) on day 7.

Conclusion:

Mouth opening restriction after BMG urethroplasty is a definite entity in the initial postoperative period, which becomes nonsignificant by 6 months. The pain has no effect on mouth opening.

Keywords: Buccal mucosa graft, mouth opening, urethroplasty

INTRODUCTION

Buccal mucosal graft (BMG) urethroplasty is a unique, durable, and versatile substitute option for the management of difficult strictures. It has become the mainstay of tissue transfer technique in substitution urethroplasty.[1] The current indications for the use of BMG are for the urethral reconstruction, which includes bulbar, penile, and pananterior urethral strictures; proximal and distal hypospadias repair where the urethral plate is insufficient; and crippled hypospadias repair where there is no sufficient genital skin, epispadias repair where the penile skin is insufficient.[2,3,4]

The advantages of BMG are that it is easily accessible, nonhair bearing, and the supply source is constant and adequate; the donor site is concealed, readily available, and has an excellent cosmetic outcome; and it is rich in elastin and collagen making and easy to handle with minimal tendency to contract. It is resistant to infection, adapts well to moist environment, and is highly vascular allowing rapid healing. Unlike the bladder mucosa, this does not cause meatal problems of protuberance, excoriation, and encrustation.[5]

In literature, it is not uncommon to observe the complications of donor site after the graft harvest. There are only a few studies in the current literature which prospectively studied the postoperative morbidity, in particular the mouth opening in long terms. It is not known whether it really makes any difference in mouth opening at the long term or whether multiple graft harvest site makes any difference in terms of postoperative pain and mouth opening. We prospectively did the objective assessment of the buccal graft harvest site mortality, mouth opening at long terms in particular and to measure the changes objectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between May 2013 and December 2014, 58 patients with stricture urethra who underwent BMG urethroplasty were prospectively included in the study. All the included patients were adult male, with a minimum age of 18 years. Those patients who continued to smoke postoperatively and fail to comply with the required regular follow-up to 6 months’ minimum were excluded from the study. The exclusion criteria also included patients refused to sign informed consent or not willing to be included and those when 2nd-time graft is taken from the same site.

The preoperative evaluation included clinical history, physical examination, urine culture, uroflowmetry, retrograde urethrography, and voiding cystourethrography. The day before surgery, the patients began using chlorhexidine mouthwash for oral cleansing and continued using it for 7 days after surgery. Patients with smoking habits were advised to quit smoking 3 weeks preoperatively and to avoid smoking postoperatively. The preoperative mouth opening (reference point between two incisors with the highest of three readings taken as final) was measured using a Vernier caliper. Harvest site was left open to heal by secondary intentions.

In postoperative period, all the patients received broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics for 2–3 days followed by oral prophylaxis for 2–3 days and continued in case of wound infection till it subsided. Analgesics were given accordingly whenever the patient complained of pain. The mouth opening using the Vernier caliper and pain scores (using self-administered VAS] were assessed on day 1, day 3, and in follow-up at 1 week, 1 month, and at 6 months follow-up.

Technique of mouth opening assessment

With the help of Vernier caliper, the mouth opening was measured from upper to lower central incisors in dentulous patients; the same was measured from upper to lower alveolus in midline in edentulous patients. The reading was taken with the highest of three readings taken as final [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a) Vernier callipers. (b) Measurements of mouth opening being taken. (c) Intra-operative buccal mucosal graft harvesting. (d) Graft is fixed on a soft board and defatted

Statistical methods

Descriptive and inferential statistical methods were used. Normality of data was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test. Data were described as mean (SD), median (IQR), or proportions (percentage). Repeated measurements of pain and mouth opening over different time intervals for same patient were measured by the choice of repeated measures parametric ANOVA or Friedman nonparametric ANOVA depending on satisfying assumption of normality. All the hypothesis testing was done assuming two-tailed distributions with significant P value set beforehand as <0.05.

RESULTS

Out of a total of 66 consecutive cases who underwent BMG urethroplasty, 58 patients who completed the study as per the protocol were included in the study. The mean (SD) age of the patients was 39.28 (SD 13.20) years. It was observed that almost 50% of the patients had some sort of adverse habits in the form of tobacco chewing (20.7%), smoking (20.7%), and khaini (a form of tobacco abuse in rural India) chewing (8.6%).

The types of urethral strictures in patients undergoing BMG urethroplasty were 16 (27.6%) bulbar urethral stricture, 8 (13.8%) penile urethral stricture, 5 (8.6%) bulbar plus penile urethral stricture, 19 (32.6%) pan-anterior urethral stricture, 8 (13.8%) had undergone lay open of urethra previously, and 2 (3.5%) cases were of failed stage 2 hypospadias repair [Table 1]. Out of this, 40 (68.97%) patients underwent dorsal onlay BMG urethroplasty, 16 (24.14%) underwent Bracka's procedure, and 4 (6.90%) underwent dorsal inlay with tubularization [Table 2]. The graft was taken from a single cheek in 50%, whereas from both cheeks, both cheeks with lip, and both cheeks with the tongue in 29.31%, 17.24%, and 3.50% cases, respectively. The average graft dimensions (length × width) from the cheek were 5.5 cm × 2 cm and from the lip and tongue was 4.5 cm × 1.7 cm.

Table 1.

The diagnosis of patients undergoing buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty (n=58)

| Diagnosis | Total patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Bulbar urethra stricture | 16 (27.6) |

| Penile urethra stricture | 8 (13.8) |

| Bulbar + penile urethera stricture | 5 (8.6) |

| Pananterior urethra stricture | 19 (32.6) |

| Postlay open | 8 (13.8) |

| Failed Stage 2 hypospadias repair | 2 (3.5) |

Table 2.

The type of surgery patients underwent (n=58)

| Type of surgery | Total patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| BMG dorsal onlay | 40 (68.97) |

| Bracka's procedure | 14 (24.14) |

| Dorsal inlay with tubularization | 4 (6.90) |

BMG: Buccal mucosal graft

On comparing mouth opening postoperatively, the mean preoperative mouth opening (5.13 cm) was significantly more than mean mouth opening on day 1 (4.34 cm), day 3 (4.48 cm), and day 7 (4.69 cm) [Table 3]. However, mean difference became insignificant by 1 month (4.91 cm), with 6 months’ values showing marginal improvement over preoperative values (5.14 cm). A similar trend was seen when results were stratified for mouth opening in cases with isolated graft harvested from the single site (single cheek) versus multiple site (combined buccal cavity and tongue or lip). There was no difference in mouth opening between preoperative values and values at 6 months postoperatively when comparing single versus multiple harvest site [Table 4].

Table 3.

Comparison of mouth opening postoperatively

| Mean (cm) | Mean difference (cm) | SE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 5.13 | |||

| Day 1 | 4.34 | 0.786 | 0.073 | <0.0001 |

| Day 3 | 4.48 | 0.652 | 0.062 | <0.0001 |

| Day 7 | 4.69 | 0.434 | 0.059 | <0.0001 |

| 1 month | 4.91 | 0.217 | 0.055 | 0.0030 |

| 6 months | 5.14 | −0.0155 | 0.013 | 1.000 |

SE: Standard error

Table 4.

Comparison of mouth opening between patients with graft harvested from one side of the buccal cavity and others (graft harvested from bilateral buccal cavity, bilateral buccal cavity and tongue, or bilateral buccal cavity and lip)

| Variable Mouth opening | Cm, mean | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Postoperative day 1 | Postoperative day 3 | Postoperative day 7 | Postoperative 1 month | Postoperative 6 months | |

| One side of the buccal cavity | 5.10 | 4.30 | 4.48 | 4.66 | 4.91 | 5.11 |

| Others (bilateral buccal cavity, bilateral buccal cavity and tongue or lip) | 5.16 | 4.39 | 4.48 | 4.72 | 4.91 | 5.18 |

| P | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 0.98 | 0.61 |

The comparison of mouth opening between patients with adverse habits (smoking, tobacco, and khaini) and those without adverse habits showed that smokers had in general reduced preoperative mouth opening in comparison to nonsmokers and they experienced higher transient restriction in mouth opening. However, they showed a similar trend in final improvement in mouth opening as nonsmokers toward the end of 6-month period [Table 5].

Table 5.

Comparison between patients with and without adverse habits

| Variable Mouth opening | Cm, mean | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Postoperative day 1 | Postoperative day 3 | Postoperative day 7 | Postoperative 1 month | Postoperative 6 months | |

| Patients without adverse habits | 5.27 | 4.49 | 4.68 | 4.98 | 5.08 | 5.26 |

| Patients with adverse habits | 4.99 | 4.19 | 4.28 | 4.41 | 4.74 | 5.03 |

| P | 0.058 | 0.091 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.052 | 0.11 |

For most of the patients, the pain was tolerable and they reported low median pain scores (VAS) 3 (2–4)/10 on day 1 and day 3 each [Table 6]. The pain scores became 0 (0–0)/10 by day 7. It was also noticed similar between the patients with graft harvested from multiple sites or in whom graft was harvested from the single site.

Table 6.

Pain scores

| Location | Median (range) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative day 1 | Postoperative day 2 | Postoperative day 3 | Postoperative day 7 | Postoperative 1 month | Postoperative 6 months | |

| Single harvest site | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 1 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) |

| Multiple harvest site | 3 (2-4) s | 3 (2-4) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 1 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) |

DISCUSSION

Humby was first to propose and report the use of the buccal mucosa in repair of hypospadias in 1941; however, it did not gain widespread use and acceptance at that time.[6] Buccal mucosa was again popularized as urethral substitute after reports by Duckett in 1995, Burger et al. in 1992, Dessanti et al. in 1992, and El-Kasaby et al.[2,3,4,7] Thereafter, BMG has been routinely used for substitution urethroplasty in anterior urethral stricture and failed hypospadias surgery.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14] There are various other free grafts described in the literature for substitution urethroplasty include tunica vaginalis, full-thickness extragenital skin, ureter, and bladder mucosa.[15,16,17,18] However, out of all these, BMG has proved to be a versatile substitute for the management of stricture urethra. It has become the mainstay of tissue transfer techniques in substitution urethroplasty.[19] The advantages of BMG include intraoral donor site, easily accessible, nonhair bearing, and the supply source is constant and adequate.

Most literature within the first decade of technique description has traditionally focused on the complications relating to technical success or failure of surgery at the recipient site with only recent literature coming up on donor site morbidity.[16] The possible complications include intraoperative hemorrhage, postoperative infection, pain, swelling, damage to the parotid duct, limitation of mouth opening, and loss or altered sensation of the cheek or lower lip through the nerve damage. Harvesting mucosa from the cheek carries less morbidity than from the inside of the lips. The damage to the surrounding structures can be avoided by careful marking of the cheek mucosa before harvesting; it is recommended that the dissection should be at least 1 cm from the opening of the parotid duct. Dissection of the buccal graft should be done in the correct plane, not too deep to injure the muscle or not too superficial to compromise graft quality.

The long-term complications include limitation in mouth opening. Wood et al. assessed the medium- and long-term morbidity of BMG harvest for urethroplasty in 110 men who underwent BMG urethroplasty.[20] Their study showed that there was initial difficulty in mouth opening seen in 67% of patients with 9% having persistent problems, which is higher as compared to the present study, which showed marginal improvement of 5.14 cm in mouth opening over preoperative values of 5.13 cm [Table 3].

Muruganandam et al. prospectively randomized 50 patients into two groups: Group 1 donor site closure versus Group 2 nonclosure of BMG harvest site and compared postoperative morbidity. The results showed that difficulty in mouth opening was maximal during the 1st week with no difference among the groups. The pain was seen to be worse in the immediate postoperative period with closure group. However, the mean postoperative pain score was 4.20 and 3.08 on day 1 in Group 1 and Group 2, which is comparable to our study. In our study, the pain was tolerable and patients reported low median pain scores on day 1 and day 3 each, which became nil by day 7. All the patients experienced only marginal increased pain if the graft was harvested from one side versus both sides of the cheek (with/without tongue/lip graft harvest). This may be due to a ceiling effect on pain experienced or good effect of pain control protocol. Another controversy in BMG urethroplasty revolves around whether to leave the harvest site open or not. Muruganandam et al., in their study, found that there was no difference in long-term morbidity whether the graft is closed or left open. They concluded that it was best to leave the harvest site open, as can be seen in our patients.[21] Similarly, Keith et al. in their prospective study on the effect of wound closure on BMG harvest site morbidity also concluded that nonclosure of harvest site patients resulted in early return to regular diet and less early perioral numbness.[22] We prefer to leave graft site open, as evidence suggest that leaving the harvest site open causes less intensity pain postoperatively and return to normal diet is early. Long term, there is no difference in mouth opening.[20,21,22,23,24,25]

The effect of smoking on restriction of mouth opening is well known and our study corroborates the same. Smokers had in general reduced preoperative mouth opening in comparison to nonsmokers, and they experienced higher transient restriction in mouth opening. However, they showed a similar trend in final improvement in mouth opening as nonsmokers toward the end of 6 months’ period. None of the patients continued to smoke after surgery, and hence, there is a clear measurement and intervention bias and thus it cannot be concluded that smoking has no impact on overall mouth opening status and improvement in restriction of mouth opening could even be aided by the cessation of smoking.

The present study focused on an objective assessment of mouth opening with stratification of results for potential confounders/co-variables such as the site of graft harvest (unilateral vs. bilateral), pain and effect of tobacco intake in any form. Our results showed no difference in mouth opening at 6 months’ postoperative period in comparison to preoperative levels assessed objectively. We believe our results are consistent with nonobjectively measured observations by other authorities of possibility of restricted mouth opening as initially the mouth opening does indeed become restricted uniformly only to recover by 6 months. Hence, one may wait 6 months before offering final view on mouth opening status.

The main limitations of the study include small sample and only 6 months of follow-up of the patients. Although the limitation of mouth opening has been reported; to the best of our knowledge, there is no study till date which has objectively assessed this parameter with any length of follow-up.

CONCLUSION

The mouth opening restriction after BMG urethroplasty is a definite entity in the initial postoperative period which is maximum on the immediate postoperative period. However, by 6 months, there is no restriction of mouth opening. Adverse habits such as smoking and tobacco chewing have a definite effect early on; however, there is no long term effect on the mouth opening. The pain by itself has no effect on mouth opening.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Simonato A, Gregori A, Lissiani A, Galli S, Ottaviani F, Rossi R, et al. The tongue as an alternative donor site for graft urethroplasty: A pilot study. J Urol. 2006;175:589–92. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duckett JW, Coplen D, Ewalt D, Baskin L. Buccal mucosa in urethral replacement. J Urol. 1995;153:1660–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dessanti A, Rigamonti W, Merulla V, Falchetti D, Caccia G. Autologous buccal mucosa graft for hypospadias repair: An initial report. J Urol. 1992;147:1081–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Kasaby AW, Fath-Alla M, Noweir AM, el-Halaby MR, Zakaria W, el-Beialy MH. The use of buccal mucosa patch graft in the management of anterior urethral strictures. J Urol. 1993;149:276. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strachan DS, Avery JK. Histology of the oral mucosa and tonsils. In: Avery JK, editor. Oral Development and Histology. NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2001. p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humby G, Higgins TT. A one stage operation for hypospadias. Br J Surg. 1941;29:84–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burger RA, Muller SC, el-Damanhoury H, Tschakaloff A, Riedmiller H, Hohenfellner R, et al. The buccal mucosal graft for urethral reconstruction: A preliminary report. J Urol. 1992;147:662–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ransley PG, Manzoni GM. Buccal mucosa graft for hypospadias. In: Ehrlich RE, Alter GJ, editors. Reconstructive and Plastic Surgery of the External Genitalia, Adult and Paediatric. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 1999. p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabbroni G, Loukota RA, Eardley I. Buccal mucosal grafts for urethroplasty: Surgical technique and morbidity. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:320–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palminteri E, Manzoni G, Berdondini E, Di Fiore F, Testa G, Poluzzi M, et al. Combined dorsal plus ventral double buccal mucosa graft in bulbar urethral reconstruction. Eur Urol. 2008;53:81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elgamal S, Ragab MM, Farahat Y, Farha OA, Elsharaby M. A prospective randomized study comparing buccal and lingual mucosal dorsal onlay graft for management of anterior urethral strictures. Tanta Med J. 2008;36:597–608. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu X, Xu Y, Song L, Zhang H. Combined buccal and lingual mucosa grafts for urethroplasty: An experimental study in dogs. J Surg Res. 2009;169:162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Das SK, Trivedi S, Dwivedi US, Singh PB. Substitution urethroplasty for anterior urethral strictures: Buccal versus lingual mucosal graft. Urol Int. 2010;84:78–83. doi: 10.1159/000273471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh O, Gupta SS, Arvind NK. Anterior urethral strictures: A brief review of the current surgical treatment. Urol Int. 2011;86:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000319501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell ME, Adams MC, Rink RC. Urethral replacement with ureter. J Urol. 1988;139:1282–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42893-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snow BW, Cartwright PC. Tunica vaginalis urethroplasty. Urology. 1992;40:442–5. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(92)90460-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendren WH, Crooks KK. Tubed free skin graft for construction of male urethra. J Urol. 1980;123:858–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehrlich RM, Reda EF, Koyle MA, Kogan SJ, Levitt SB. Complications of bladder mucosal graft. J Urol. 1989;142:626–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhargava S, Chapple CR. Buccal mucosal urethroplasty: Is it the new gold standard? BJUI Int. 2004;93:1191–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood DN, Allen SE, Andrich DE, Greenwell TJ, Mundy AR. The morbidity of buccal mucosal graft harvest for urethroplasty and the effect of nonclosure of the graft harvest site on post operative pain. J Urol. 2004;172:580–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132846.01144.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muruganandam K, Dubey D, Gulia AK, Mandhani A, Srivastava A, Kapoor R, et al. closure versus nonclosure of buccal mucosal graft harvest site: Prospective randomized study on post-operative morbidity. Indian J Urol. 2009;25:72–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.45541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keith R, Shari M, Blair SM. Effect of wound closure on buccal mucosal graft harvest site morbidity: Results of randomised prospective trial. BJU Int. 2012;79:443–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triana RJ, Murakami CS, Larrabee WF. Skin grafts and local flaps. In: Papel ID, editor. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2009. p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGregor AD, McGregor IA. Free Skin grafts. In: McGregor AD, McGregor IA, editors. Fundamental Techniques of Plastic Surgery and their Surgical Applications. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dublin N, Stewart LH. Oral Complications after buccal mucosal graft harvest for urethroplasty. BJU Int. 2004;94:867–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]