Gender identity refers to an individual’s innate sense of self in the context of gender and may not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Gender-diverse or transgender individuals are those who experience any discordance between their gender identity and sex assigned at birth. According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, gender-diverse identities are more prevalent than previously recognized, with 1.8% of high school–aged students identifying as transgender.1 Gender-diverse youth (GDY) experience high rates of discrimination and victimization as well as mental health disparities including increased depression, anxiety, and suicidality.1,2 Previous studies suggest that family support and acceptance have the potential to mitigate existing health disparities.2,3 Some parents experience anxiety or fear in response to learning their child’s gender identity.4 They may lack understanding of gender-diverse experiences and knowledge of resources available, which can make it difficult for parents to affirm their child’s identity.3 Parental support is beneficial for all young people and, given the health disparities that GDY experience, strategies to empower parents to better support their gender-diverse children should be explored.4,5

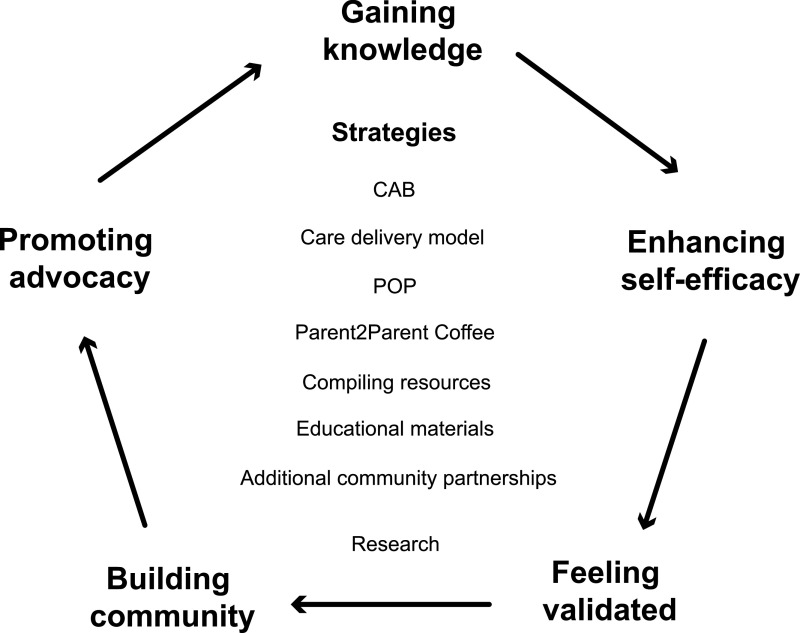

Peer support programs have been implemented to help parents of other pediatric patient populations increase their ability to navigate challenges when caring for their children,6,7 but this has not been well documented in parents of GDY. After reviewing peer support literature and consulting with parents of GDY, we conceptualized a theoretical framework (Fig 1) that identifies factors promoting parent support surrounding a list of strategies employed to facilitate this for families in our clinic.

FIGURE 1.

Community-informed parent support framework.

In this article, we describe our experiences partnering with local parents of GDY to better support our patients and families. Our authorship team includes a social worker (C.T.) and 2 physicians (K.M.K. and G.M.S.) as well as the mother of a gender-diverse child (J.D.B.). Two authors (C.T. and G.M.S.) identify as members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning (LGBTQ) community.

When my son first came out as transgender, I did not know how to best take care of him because I did not understand what being transgender meant. My husband and I felt alone and isolated from friends, family, and the community we once knew. My family and I first experienced a sense of comfort, acceptance, and community at a parent-run potluck dinner. This potluck has now become a regular event hosted by the Pittsburgh Chapter of PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays), an organization that has played an important role in the development of our parent support programs. This partnership began in April of 2018 when a provider from the gender clinic was invited to attend the potluck. She intended to discuss the details of the clinic but was willing to listen to our perspectives instead. We needed space to talk about our experiences parenting gender-diverse children and how we could better support families in the future.

J.D.B.

Community Advisory Board

Through this meeting, we learned that we needed to find a way to embed parents into the infrastructure of our rapidly expanding gender program. A smaller group of dedicated parents stayed late, exchanged contact information, and scheduled an additional time to meet. This group of parents, along with GDY and gender-diverse adults, formed a community advisory board (CAB) and began meeting with providers from our gender clinic monthly at a local coffee shop. This partnership has profoundly changed the way we provide care to youth in our gender clinic.

Care Delivery Model

The CAB expressed the importance of providing parents with the opportunity to speak openly about their concerns during the first visit to our gender clinic. In response, we now begin and end visits collaboratively, and a behavioral health provider meets with parents while the medical provider speaks to the patient alone. During this time, parents often verbalize fears and share questions they hesitate to ask in front of their child. This also allows our team to validate parental concerns, engage in problem-solving, and offer education, resources, and support.

The Parent Outreach Program

We learned that one of the most critical pieces in parenting a gender-diverse child is connecting with other parents of GDY. Our partnership with parents of GDY in the CAB allowed us to facilitate these connections by creating the Parent Outreach Program (POP). The POP matches interested parents of gender-diverse children with a CAB parent for individualized peer support. Parents of new patients are given the option to connect via phone, e-mail, or in person and can do so as little or as much as they want.

Within the first few months of implementing the POP, we heard from patients, parents, and the CAB that this program was extremely beneficial. CAB parents described witnessing parents learn and grow by changing the words they used with their child and the thoughts and feelings they had about medical interventions. Gender-diverse patients described seeing an increase in their parents’ comfort talking about their identity and experiences. Parents returned to our clinic more apt to advocate for their child’s needs. One parent expressed that this connection “was the pivotal point in our son’s health and it was through our friendship that we were able to walk this journey with him.”

“B” is a patient we met during his first visit to our gender clinic, and it was clear that he was nervous. He explained that his parents were struggling with his gender identity and he doubted they would ever see him for who he truly was. B’s parents were connected with J.D.B through the POP that day.

I met B’s mom through the POP. During our first conversation, she shared that she was angry, frustrated, sad, and frightened after their initial visit to the gender clinic. She was so afraid of making the wrong decisions and did not want to rush into a treatment plan. Her child was suicidal and she was terrified. Her child’s sibling was using affirming pronouns, and it upset her, because she was not ready to do that. I shared my journey with my own transgender son. I told her about the challenges I faced with my faith, as this was something we shared. Our families met, and her husband told mine that he was so grateful that he no longer felt alone in this journey.

J.D.B.

When B and his family returned to clinic a few months later, he was a different person, and so were his parents. They came into the visit using B’s affirmed name and pronouns and asking questions about medical options and how they could better support their son. While speaking with him alone, we asked him what changed. He said that his mom met another mom and “it changed everything.” A year later, B is no longer suicidal, and his parents describe feeling like they got their child back and are so proud of the young man he is becoming. Additionally, his mother is now a valued member of our CAB and has begun to support other parents in our community.

Our Process

New parents frequently ask the same questions. “Am I doing the right thing?” “How will society, family, friends, faith-based groups, and educational institutions treat my child when they transition?” “Can my child survive this?” Early on, CAB parents expressed the importance of having space to gain self-efficacy in affirming their children rather than being explicitly told how to do so. Therefore, they both advocate for GDY and provide validation to parents who are struggling to accept their child’s identity. To facilitate this process, CAB parents often share their own story and answer questions when providing peer support. This approach can be emotionally taxing and is not something all parents can do. We consider new parents for the CAB after they have demonstrated this ability during monthly PFLAG meetings. We have also developed opportunities for parent volunteers to receive their own support from medical and mental health providers within the CAB and prioritize time during our monthly meetings to process challenging interactions. The CAB parents also lean on one another after difficult conversations and are encouraged to contact on-call providers for guidance.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its success, we faced some logistic challenges regarding matching parents during clinical encounters and trying to expand the POP to other local clinics supporting GDY. We shifted the POP from being a clinic-based program to one that was community based and housed within PFLAG. The CAB parents’ connection to our local PFLAG chapter enabled us to create a parent support phone number and e-mail address that are easily disseminated throughout our community. We also realized that talking with another parent through the POP may be intimidating for some parents, and large PFLAG meetings may be overwhelming as well. In response, a CAB parent (J.D.B.) volunteered her personal time to create and host “Parent2Parent Coffee.” These are monthly meetings at a local coffee shop or library where a small group of parents of gender-diverse children could connect with CAB members to ask questions, cry, laugh, or just listen.

A limitation of our group is a lack of diversity. The CAB is predominantly white identifying with a limited number of religious affiliations and socioeconomic backgrounds. This is likely associated with a lack of racial diversity among patients receiving care in our clinic,8 which has also been noted in other gender clinics across the United States.9,10 We hope to include more people of color as well as different faith practices and diverse experiences in the future to improve the care we provide and better understand how intersecting identities impact the barriers families may face. The CAB is actively seeking opportunities to connect with community-based organizations that primarily serve people of color and with leaders of various religious communities to fill this gap.

Future Directions

The CAB has sought additional opportunities to support local gender-diverse young people and their families. We created educational brochures about gender-diverse identities that include testimonials from parents of GDY. CAB parents also suggested that families initiating care could benefit from speaking with a parent of a gender-diverse young person after their visit and have begun working with a community-led initiative partnering trained volunteers with patients to help them navigate the medical system. This partnership has allowed CAB members to meet with parents in the clinic and connect them to resources and community support immediately. Because of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, our meetings have temporarily moved online, which has allowed us to reach parents who experience transportation barriers. We plan to continue both online and in-person meetings moving forward and have encouraged parents without Internet access to connect with their POP match via phone.

The CAB has aided in conceptualization and conduct of research to better understand the parent and family experience of supporting gender-diverse young people. The CAB has helped to create and test a scale measuring empowerment among caregivers of GDY, and members are currently sharing their stories as a part of a qualitative research study. CAB members are also working on helping us share research findings through online groups and local and national speaking engagements. Given the dearth of research that is focused on the experiences of this population, partnerships like this have the potential to impact GDY, their families, and the providers who care for them. Ultimately, the CAB plans to continue to support parents of GDY through this work and has begun to expand from our local community to neighboring states and across the country.

GDY are healthier when they are supported by their family.2,5 Our work suggests families are best able to affirm the young people in their lives when they are supported by their community and able to engage with parents who have shared experiences. Parent-led peer support programming and advising is a promising component of pediatric gender care. We hope that by sharing the programming our clinic developed in partnership with a dedicated group of parents, other clinics may consider similar interventions and further study the impact of this work.

Acknowledgments

We thank the amazing group of parents and community members who have been integral to this program. We specifically thank Rosie Benford, Joel Burnett, Oliver Burnett, Kelly Dembiczak, Kyle Dembiczak, Jamie Mullin, January Furer, Alexandra Lynn, Katia Nascimento, Alicyn Simpson, Dave West, and Michele West.

Glossary

- CAB

community advisory board

- GDY

gender-diverse youth

- PFLAG

Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays

- POP

Parent Outreach Program

Footnotes

Ms Thornburgh and Drs Kidd and Sequeira conceptualized, designed, and drafted the manuscript; Dr Burnett (parent author) conceptualized, designed, and drafted the manuscript and provided numerous quotes for incorporation into the final manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded by the following grants: T32 HD71834-5 (PI: Terence Dermody, MD) T32 HD087162 (PI: Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD), TL1TR001858 (PI: Wishwa N. Kapoor, MD, MPH) from the National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, et al. Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students - 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(3):67–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson KR, Durwood L, DeMeules M, McLaughlin KA. Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20153223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz-Wise SL, Budge SL, Orovecz JJ, Nguyen B, Nava-Coulter B, Thomson K. Imagining the future: perspectives among youth and caregivers in the trans youth family study. J Couns Psychol. 2017;64(1):26–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillier A, Torg E. Parent participation in a support group for families with transgender and gender-nonconforming children: “Being in the company of others who do not question the reality of our experience”. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):168–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons L, Schrager SM, Clark LF, Belzer M, Olson J. Parental support and mental health among transgender adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(6):791–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chernoff RG, Ireys HT, DeVet KA, Kim YJ. A randomized, controlled trial of a community-based support program for families of children with chronic illness: pediatric outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(6):533–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shor R, Birnbaum M. Meeting unmet needs of families of persons with mental illness: evaluation of a family peer support helpline. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48(4):482–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sequeira GM, Ray KN, Miller E, Coulter RWS. Transgender youth’s disclosure of gender identity to providers outside of specialized gender centers. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(6):691–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson J, Schrager SM, Belzer M, Simons LK, Clark LF. Baseline physiologic and psychosocial characteristics of transgender youth seeking care for gender dysphoria. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(4):374–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen M, Fuqua J, Eugster EA. Characteristics of referrals for gender dysphoria over a 13-year period. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(3):369–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]