Firstly, I'd like to take this opportunity to offer all BDJ readers my sincere best wishes in what has been a trying 2020 so far. At the beginning of a new decade, heralded by many as a fresh chance for humanity to embrace and nurture all that is positive in global and local society, we find ourselves having to re-adjust radically, both personally and professionally in such unusual times, to a new 'norm' and there is still much to evolve in this regard. I have purposely avoided the over-used descriptor, 'unprecedented' to describe the events that have transpired. Pandemics are not unprecedented. Indeed, they have and continue to affect humankind with a certain biological regularity over history. What is unprecedented is the reaction of humankind. As society has begun the complex reactionary re-adjustment, it is clear that in the healthcare sector, many work practices and tenets of care delivery will be forced to change. Positive opportunities need to be taken by all stakeholders in dentistry involved in delivering the best oral healthcare management to patients. These stakeholders include the clinical/research profession, educators, the needs, wants and expectations of the public/patients, industry partners, service providers, indemnity associations and service regulators. Therefore, this second minimum intervention (MI)-themed issue is in my opinion, quite timely in its planning, production and release.

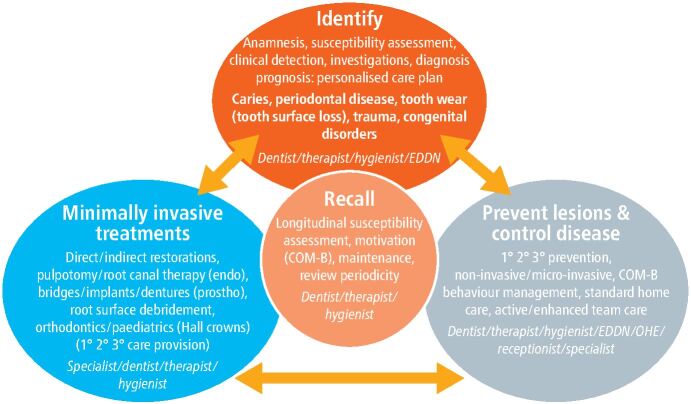

MI association with the BDJ began in early 2012. An informative series of MI-related papers in conservative dentistry had been published in a French journal, Réalités Cliniques, the previous year. I felt compelled to speak to my dear friend, colleague and BDJ editor-in-chief, Stephen Hancocks to see if these could be adapted and reprinted in the BDJ, so increasing their exposure to a wider audience. He agreed and hey presto, in 2012 and 2013 in BDJ volumes 213 and 214, they were published and proved to be of real interest and inspiration to the readership. Suitably enthused, in 2013, Stephen then kindly invited me to author an editorial opinion piece introducing and outlining the concept of prevention-based minimum-intervention oral care (MIOC) provision and the challenges it might face in gaining acceptance in the mainstream profession.1 The MIOC team-delivery framework is based around four interlinked domains, applicable to any of the restorative disciplines, across all ages and patient groups (with suitable adaptions where necessary) (Figure 1):

Identifying problems (detection, risk/susceptibility assessment, diagnosis and patient-focused care planning)

Prevention & control (primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of lesions, control of the disease process)

MI treatments/procedures (minimally invasive operative management of carious/periodontal lesions, pulp pathology, broken-down or missing teeth)

Review/recall (reassessment of any treatment provided, patient behavioural adherence to change, recall periodicity dependent on longitudinal susceptibility assessments).1

Fig. 1.

The MIOC framework applied to the different disciplines within restorative dentistry (conservative dentistry and endodontics, periodontology, prosthodontics and orthodontics), showing the four interlinked domains and the oral healthcare team members responsible in each (EDDN - extended duties dental nurse, OHE - oral health educator). Minimally invasive operative dentistry forms one of the domains within the MIOC framework for delivering better oral health. TSL - tooth surface loss

Four years later, I was again delighted and honoured this time to coordinate, co-author and present the first MI-themed BDJ issue as its guest editor, commissioning a selection of high quality manuscripts from national and international renowned professionals and dear colleagues with an acknowledged expertise in MI dentistry.2 As can be seen from the range of papers published in that issue, alongside many other important publications in the dental literature, the clinical academic evidence for MI dentistry is now far-reaching and more widely accepted as to be considered a mainstream approach in the profession and not solely for caries management as many still perceive. The advances in clinical operative techniques/technologies/materials, behaviour management and another form of MI, motivational interviewing, are all enabling oral healthcare teams to deliver successfully this contemporary approach to achieve and maintain oral health and long term wellbeing in our patients.3,4,5,6 However, even with such evidence laid bare, it is clear that the uptake of minimally invasive operative principles/approaches, for example in caries management, is not universal in primary care practice.7,8 Therefore, it is timely that in 2020 this second MI-themed issue has been published, collating international experts' outputs on how the accepted principles of MIOC/minimally invasive operative dentistry (MID) can be implemented in the broader world of 'real-life' primary care dentistry, for the benefit of our patients long term.

This issue, which should be read and digested in conjunction with the contents of the first MI-themed issue, focuses on clinical implementation strategies across the various disciplines of clinical dentistry that primary care practitioners and their teams experience on a daily basis. One year ago, I gave the authors the brief to summarise knowledge and offer potential solutions/guidance for the use of MIOC principles to manage day-to-day patients seen in a non-specialist, primary care setting. The clinical disciplines covered in this issue include, in no particular order, orthodontics, cariology (including detection technologies, an update of restorative biomaterials and consensus guidelines of when to intervene in the caries process), periodontology, prosthodontics, paediatrics and the MI restorative management of the anxious/phobic patient. The implementation challenges of MIOC across the world are discussed, using the US as a specific example. It is clear from these insightful papers that the underlying tenet of patient-focused, oral healthcare team-delivery is applicable to all patients, at all stages of their lives, whether disease-active or in health. Indeed, the underpinning strength of the MIOC framework domains is the continuity of care with underlying team-delivered communications to patients, to value and take responsibility of their own general and oral health. This message has never been as pertinent and meaningful as it is now.9

MIOC underpins care throughout the life-course

Dental caries is still one of the most prevalent non-communicable diseases affecting humankind globally.10 There is clear need and benefit to have guidance as to how to deliver MIOC and MID to individuals, local regions and country-specific populations. Of course, as all clinicians appreciate, there is always variation between practitioners as to how to resolve particular clinical challenges, with many, often subjective, factors to be taken into account. To help in such instances, it is useful to have guidelines/standard operating protocols (SOPs) to help oral healthcare teams to manage their patients. These cannot be restrictive rules and regulations; they should be a learned summation of the current, collated expert consensus, scientific and clinical evidence, however strong or weak these may be, to be considered along with the individual patient, practitioner and local factors pertaining to each clinical scenario/patient and adapted accordingly.11 In this way, each patient receives optimal care and the team/practitioner can feel confident in their approach and can also learn from others/add to their clinical experience and acumen, collectively. The implementation of such consensus guidelines needs to be accompanied with careful communication and documentation between the team and patient of decisions made and the reasons as to why.

So, where are MI guidelines? What evidence, if any, should be considered, accepted or discarded?11 Which stakeholders are responsible for generating and updating them? How can guidelines be validated locally, regionally, nationally or globally? Should there be nationwide/global coordination/training?

There are many important guideline publications available for each of the different disciplines in restorative dentistry, including periodontology, prosthodontics and endodontics. These often concentrate on standardising specific operative treatment protocols for more clearly defined clinical situations. These are published by expert panels representing learned societies, royal colleges and government bodies. These groups are sometimes assisted by industry partners to help convene the discussions. It is important, however, that industry partners do not influence the outcomes and these are kept strictly independent to avoid inappropriate bias.

Through such adversity comes the glimmer of opportunity to change and develop new strategies and mechanisms to deliver better oral health programmes

The discipline of conservative & MI dentistry in primary care covers a great breadth and variety of clinical situations affecting a large, heterogeneous population. Many management variables (technologies, procedures, materials, operator skills, knowledge, experience and a multitude of patient factors including attitudes/behaviour/socio-economic status etc) all need to be considered when attempting to develop suitable treatment guidelines to help practitioners and their teams.12 Thanks to this complex interaction of variables, there is a relative paucity of clear-cut, high quality evidence (for example, randomised controlled clinical trials) to enable such guidance to be absolute, conclusive and applicable to all scenarios. As an example of a response to collate further high quality clinical evidence, the National Institute for Health Research UK (NIHR) is currently funding two national multi-centre primary care randomised controlled trials, one on minimally invasive operative caries management - Selective Caries Removal in Permanent Teeth (SCRiPT), and the other on pulpotomy for the management of irreversible pulpitis in mature teeth (PIP). These studies provide an exciting opportunity for NHS primary care dentists and their teams to get involved with 'real-life' clinical trial data collection which will contribute to the evidence base to support advances in service provision (practice expenses are covered and eCPD awarded when participating in the trials - please email script@dundee.ac.uk / PIP-Study@dundee.ac.uk for further information about participation in these trials).

In conservative & MI dentistry including endodontics, there are many national and international learned societies and consensus panels, all providing useful information about the terminology, prevention and management of caries,13,14,15,16,17 toothwear18 and management protocols for broken-down teeth. The European Federation of Conservative Dentistry (EFCD) and the European Organisation for Caries Research (ORCA) have collaborated in an attempt to collate and generate pragmatic, evidence-based guidance for primary care practitioners.19,20,21,22,23 These, along with many other published efforts, are trying to help the relevant stakeholders to manage patients, improve oral health linked to general health and increase awareness in populations of their role in valuing and taking responsibility for their personal healthcare future.24,25 Education and training courses exist to help dentists, dental therapists and team members learn about and implement MIOC (for example, the online, distance-learning master's programme in Advanced Minimum Intervention Dentistry).

MIOC and the post-pandemic era

A further consequence of the global COVID-19 pandemic is the generation of a multitude of new terminologies and abbreviations. PPE (personal protective equipment for the general public at least), UDC (urgent dental care), furlough, AGP (aerosol generating procedure), AGE (aerosol generating event), FFP2/3, BAPD (British Association of Private Dentistry), abatement, social distancing are a small selection of the professional terms now commonplace in our collective vocabulary. But what about dentistry in the the post-pandemic era?

As I mentioned at the beginning of this piece, few, if any, could predict the dramatic changes in global health and economic outlook over the last few months and only time will tell as to how this manifests and moulds our new norms, personally, professionally and across broader society. However, through such adversity comes the glimmer of opportunity to change and develop new strategies and mechanisms to deliver better oral health programmes for our patients. National and international regulators will have to decide the new norms for social distancing at work, personal protective equipment and suitable infection prevention and control policies. Will the more limited use of aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs) be encouraged beyond the short-term advice already actioned? Personalised preventive oral health advice via online, teledentistry delivery may, or indeed should, become a funded aspect of primary care delivery, helping to evolve the relationship between 'oral health practices' and their patients. This may in turn improve the reach and access to the more under-served parts of the population. I have been invited to assist the Office of the Chief Dental Officer in England in taking forwards the initiative to develop and coordinate such clinical strategies and protocols, using these strange times as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to re-shape and augment the underlying clinical philosophy, building on the MIOC framework across the dental disciplines to align this model of care with the phased recovery period. This should be accompanied by revised contracts and more agile NHS commissioning while ensuring resilience of the approach through local peer support, enhanced team-delivery and training provision. Government messaging to the population will need to be more balanced in this regard than ever before, where prevention, self-care, personal responsibility and awareness are given maximum priority in oral health promotion. Service providers, regulators and the legal/indemnity profession will have to engage more in working together towards this common goal as opposed to the somewhat continued defensive, siloed, inward-focused attitudes that still seem to prevail in times of greatest need.

The maintenance of optimal oral health, inseparable from systemic health and physical/mental wellbeing, has never been so important and at the forefront of people's minds and agendas. Suffice it to say, there is a hope that all stakeholders will finally start to value aspects of their own lives as well as of those whom they represent that were once, perhaps, taken for granted. Maybe, just maybe, delivering better oral health through the MIOC framework may be one of those paradigm shifts for the better.26

References

- 1.Banerjee A. 'MI'opia or 20/20 vision? Br Dent J 2013; 214: 101-105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Banerjee A. 'Minimum intervention' - MI inspiring future oral healthcare? Br Dent J 2017; 223: 133-135. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Banerjee A, Doméjean S. The contemporary approach to tooth preservation: minimum Intervention (MI) caries management in general dental practice. Prim Dent J 2013; 2: 30-37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Banerjee A. The contemporary practice of MID. Faculty Dent J (RCS Eng) 2015; 6: 78-85.

- 5.Green D J, Mackenzie L, Banerjee A. Minimally invasive long term management of direct restorations: the '5Rs'. Dent Update 2015; 42: 413-426. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Martins B M d C, da Silva E J N L, Ferreir D M T P, Reis K R, Fidalgo T K d S. Longevity of defective direct restorations treated by minimally invasive techniques or complete replacement in permanent teeth: A systematic review. J Dent 2018; 78: 22-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Zebic L, Ezzeldin M, Patel V et al. Caries prevention for children in a primary care setting - a collaborative clinical audit. Br Dent J 2018; 224: 809-814. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Chana P, Orlans M.C, O'Toole S, Doméjean S, Movahedi S, Banerjee A,. Restorative Intervention Thresholds and Treatment Decisions of General Dental Practitioners in London. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 727-732. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Sculean A, Banerjee A, Petersen P E. Editorial: Prevention and personal responsibility. Oral Health Prev Dent 2016; 14: 3-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019; 393: e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Sackett D L, Rosenberg W M C, Grey J A M, Haynes R B, Richardson W S. What is evidence-based medicine? Br Med J 1996; 312: 71.

- 12.Martignon S, Pitts N B, Goffin G et al. CariesCare Practice Guide: Consensus on Evidence into Practice. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 353-362. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Schwendicke F, Frencken J E, Bjorndal L et al. Managing caries lesions: consensus recommendations on carious tissue removal. Adv Dent Res 2016; 28: 58-67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Innes N P T, Frencken J E, Bjorndal L et al. Managing caries lesions: consensus recommendations on terminology. Adv Dent Res 2016; 28: 49-57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Machiulskiene V, Campus G, Carvalho J et al. Terminology of Dental Caries and Dental Caries Management: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by ORCA and Cariology Research Group of IADR. Caries Res 2020; 54: 7-14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Banerjee A, Frencken J E, Schwendicke F, Innes N P T. Contemporary operative caries management: consensus recommendations on minimally invasive caries removal. Br Dent J2017; 223: 215-222. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Duncan H F, Galler K M, Tomson P L et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: Management of deep caries and the exposed pulp. Int Endod J 2019; 52: 923-934. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Toothwear-themed issue. Br Dent J 2018 224.

- 19.Schwendicke F, Splieth C, Breschi L et al. When to intervene in the caries process? An expert Delphi consensus statement. Clin Oral Invest 2019; 23: 3691-3703. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Splieth C H, Banerjee A, Bottenberg P et al. How to intervene in the caries process in children? A joint ORCA and EFCD expert Delphi consensus statement. Caries Res 2020: DOI: 10.1159/000507692. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Splieth C H, Kanzow P, Wiegand A, Schmoeckel J, Jablonski-Momeni A. How to intervene in the caries process: proximal caries in adolescents and adults - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Invest 2020; 24: 1623-1636. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Schwendicke F, Splieth C H, Bottenberg P et al. How to intervene in the caries process in adults: Proximal and secondary caries? An EFCD-ORCA-DGZ expert Delphi consensus statement. Clin Oral Invest 2020; 24: 3315-3321. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Paris S, Banerjee A, Bottenberg P et al. How to intervene in the caries process in older adults? A joint ORCA and EFCD expert Delphi consensus statement. Caries Res: In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Askar H, Krois J, Göstemeyer G et al. Secondary caries: What is it, and how can it be controlled, detected and managed? Clin Oral Invest 2020; 24: 1869-1876. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Costa R L, Bendo C B, Daher A et al. A curriculum for behaviour and oral healthcare management for dentally anxious children - recommendations from the Children Experiencing Dental Anxiety: Collaboration on Research and Education (CEDACORE). Int J Paed Dent 2020; 30: 556-569. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Hurley S. Why re-invent the wheel if you've run out of road?. Br Dent J 2020; 228: 755-756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]