Abstract

Background

As a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, many Pediatric Surgery Fellowship programs were forced to convert their normal in-person interviews into virtual interviews. This study sought to determine the perceived value of virtual interviews for Pediatric Surgery Fellowship.

Methods

An anonymous survey was distributed to the applicants and faculty at a university-affiliated, free-standing children's hospital with a Pediatric Surgery fellowship program that conducted one of three interview days using a virtual format.

Results

All applicants who responded to the survey had at least one interview that was converted to a virtual interview. Faculty (75%) and applicants (87.5%) preferred in-person interviews over virtual interviews; most applicants (57%) did not feel they got to know the program as well with the virtual format. Applicants and faculty felt that virtual interviews could potentially be used as a screening tool in the future (7/10 Likert) but did not recommend they be used as a complete replacement for in-person interviews (3.5-5/10 Likert). Applicants were more likely than faculty to report that interview type influenced their final rank list (5 versus 3/10 Likert).

Conclusions

Faculty and applicants preferred in-person interviews and did not recommend that virtual interviews replace in-person interviews. As the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic continues, more virtual interviews will be necessary, and innovations may be necessary to ensure an optimal interview process.

Type of study

Survey.

Level of evidence

N/A.

Keywords: Pediatric surgery, Fellowship, Virtual interviews, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Pursuit of additional fellowship training after General Surgery Residency has become the primary pathway for graduating residents1 and Pediatric Surgery remains the most competitive surgical subspecialty.2 While many factors are associated with successfully matching into a Pediatric Surgery Fellowship position,3 the critical nature of the interview process has long been acknowledged.4 These fellowship interviews typically take place in January through April, 15-18 mo in advance of the start date of fellowship training. This year, because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, the typical process was disrupted, requiring programs and applicants to rapidly adapt.

Pediatric Surgery Fellowship programs interview between 20 and 27 applicants on average,5 , 6 and the number of interviews that residents travel to has been increasing from an average of 8-12 programs in 2014, up to 18 interviews more recently in 2017.7 , 8 This process comes at significant financial cost to the applicants, who spend on average between $7000-$9,000, with many spending substantially more on application fees and travel for interviews.8 , 9 In addition, this travel is disruptive to the home training program, as frequent absences from clinical duty obligations may occur, and to personal lives, as families, significant others, and pets experience these periods of absence as well.

In early 2020 in the United States and Canada, increasing concerning over COVID-19 resulted in travel warnings or restrictions and shelter-in-place regulations beginning in the middle of interview season. Pediatric Surgery fellowship programs scrambled to make appropriate accommodations, and many turned to virtual interviews. This study sought to determine the perceptions and perceived value of virtual interviews in the Pediatric Surgery fellowship interview process by both the applicants and faculty.

Methods

Institutional details and ethics approval

Institutional Review Board approval (#20-07288-XM) was obtained to conduct this study at a university-affiliated, free-standing children's hospital with a Pediatric Surgery fellowship program, geographically located in the southern United States. Because of COVID-19, the last of three scheduled interview days was converted into a virtual interview process. Interviews were conducted using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc, San Jose, California).

Interview process structure

The in-person interview process at this program consists of an optional meet and greet preinterview day dinner where applicants are able to meet the faculty, fellows, and nurse practitioners. The next morning, the program director, program coordinator, and the senior fellow give an introduction and an overview of the program. Interviews, 30 min each with either 1-2 faculty members or fellows per interview, then take place for a total of 8-9 interviews. The applicant group is reconvened for lunch with the nurse practitioners. Applicants are then taken on a guided tour of the main hospital and affiliated offsite hospital by the fellows. Finally, there is a wrap-up meeting with the program director to allow time for any remaining questions from the applicants.

The interview day was recreated for the virtual interview day held in March 2020. Similar to in-person interviews, the program director gave an introduction and the senior fellow presented a video about the program. Using Zoom breakout sessions, applicants then had 8-9 thirty-minute interviews with faculty members and fellows. Rather than lunch with affiliated staff, the program director held a wrap-up meeting after interviews was over. A virtual tour of the main hospital was provided in video form.

Survey details

A 17-question survey was created for applicants, and a 7-question survey was created for faculty using QuestionPro, a web-based survey platform (QuestionPro Inc, Austin, TX). The survey questions can be found in Appendix A and B. Whenever applicable, a ten-point Likert scale was used asking participates to rank their answer from 1 to 10. Survey questions asked of both faculty and applicants included overall satisfaction with in-person and virtual interviews, how well they got to the know the applicant or faculty member when using each interview type, how much interview type influenced final rank list, and how likely they were to recommend virtual interviews in the future. Fellowship applicants were also asked about the influence of COVID-19 on other interviews and the financial burden of interviews. A consent form preceded each survey and continuation to the survey served as informed consent.

Surveys were sent to all participating faculty members who interviewed applicants. Surveys for applicants were sent to all applicants who applied to the fellowship program, regardless of their interview status at this program. All survey results were anonymous. Surveys were distributed by e-mail after programs' and applicants' final rank lists were submitted. Several reminder e-mails were sent, and surveys were closed after 1 mo. Given the continuously evolving situation during the COVID-19 pandemic and the many competing demands of fellowship applicants, our a priori expected response rate from applicants was 20%. Participants did not receive any financial compensation for completion of the survey. Continuous variables were analyzed by Student's t-test when appropriate.

Results

Twenty applicants interviewed at this program in 2020. Seven participated in the virtual interview day that replaced the March interview date. No applicants declined to participate in the virtual interview. Surveys were sent to 9 faculty members who participated in both in-person and virtual interviews; eight completed the survey for a response rate of 89%. Sixty-two applicants applied for the Pediatric Surgery Fellowship position; 22 started the survey, of which 14 completed the survey (68%), for a final response rate of 22.6%.

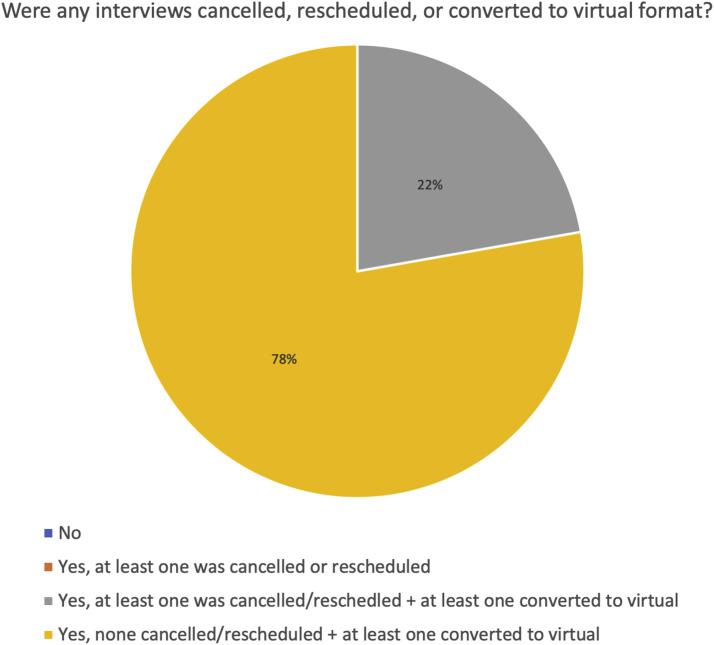

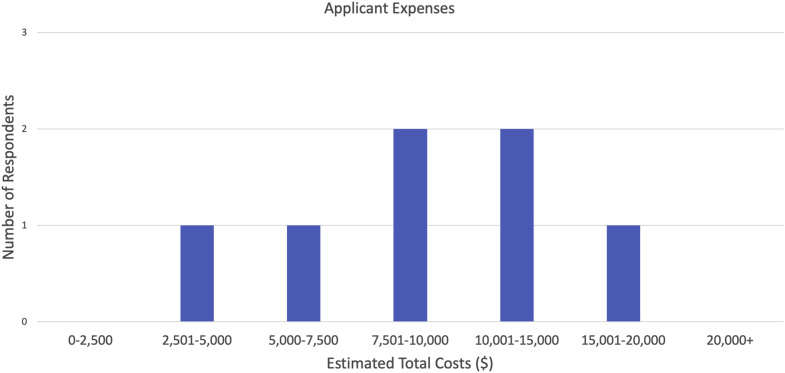

When asked how interviews were affected by COVID-19, two applicants reported that at least one of their interviews had been canceled or rescheduled and at least one has been converted to a virtual format. Seven reported that at least one interview had been converted to a virtual format without any others being canceled or rescheduled [Fig. 1 ]. Applicants were also asked regarding total estimated costs including applications and travel expenses. Four of the seven respondents reported costs between $7500-15,000 [Fig. 2 ].

Fig. 1.

Impact of COVID-19 on Pediatric Surgery Fellowship interviews. The first question of the applicant survey asked if any interviews were canceled, rescheduled, or converted to a virtual format as a result of COVID-19. (Color version of figure is available online.)

Fig. 2.

Financial burden of interviewing for Pediatric Surgery Fellowship. Applicants were asked their estimated total costs of the entire interview process, including applications and travel expenses. (Color version of figure is available online.)

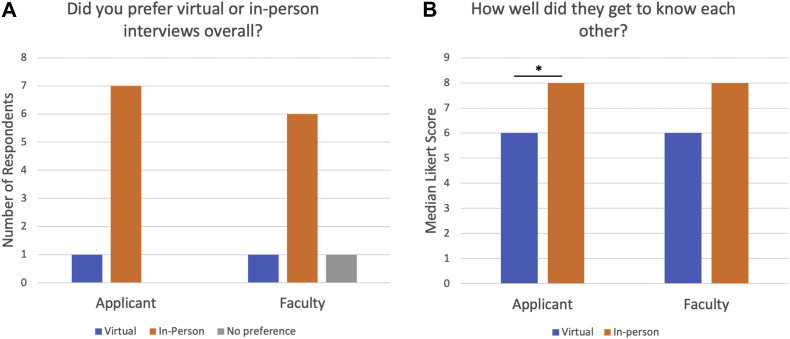

Both applicants and faculty surveyed stated they preferred in-person interviews over virtual interviews [Fig. 3 A]. One of seven applicants preferred virtual interviews. One of eight faculty members preferred virtual interviews, one stated no preference, and six preferred in-person interviews. Applicants were asked how well they felt they got to know the program on a scale of 1-10 when conducting in-person versus virtual interviews; for in-person interviews, the median response was 8 (range 7-10), and for virtual interviews, the median response was 6 (range 5-7, P = 0.002). Faculty were similarly asked how well they felt they got to know the applicants when conducting in-person versus virtual interviews; the median response for faculty was 8 (range 6-9) for in-person interviews and 6 (range 5-8) for virtual interviews (P = 0.11) [Fig. 3B].

Fig. 3.

Applicant and faculty preferences for virtual versus in-person interviews. (A) Applicants and faculty were asked if they preferred virtual or in-person interviews overall. (B) Applicants and faculty were asked how well they felt they got to know each other in-person versus virtually. ∗P < 0.05. (Color version of figure is available online.)

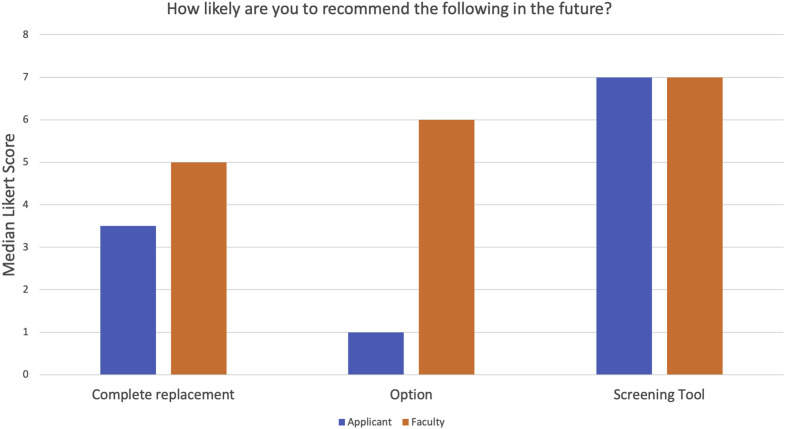

Next, applicants and faculty were both asked how likely they were to recommend virtual interviews in the future as complete replacements, as an option, or a screening tool, again using a Likert scale of 1-10 [Fig. 4 ]. There was a wide range of responses for these questions. If virtual interviews were used as complete replacements, the median response for applicants was 3.5 (range 1-10) and for faculty was 5 (range 1-8). When asked if virtual interviews could be used as an option where applicants were given the choice of either, applicants gave a median response of 1 (range 1-8) and faculty gave a median response of 6 (range 1-9). Finally, when asked if virtual interviews could be used a screening tool before formal interviews, applicants gave a median response of 7 (range 4-10) and faculty gave a median response of 7 (range 1-10).

Fig. 4.

Applicant and faculty recommendations for future use of virtual interviews. Applicants and faculty were asked how likely they were to recommend virtual interviews, either as a complete replacement, an option given to applicants, or as a screening tool used before formal interviews. (Color version of figure is available online.)

Finally, applicants and faculty were also asked which type of interview influenced their rank lists. Applicants gave a median response of 5 (range 2-8) and faculty gave a median response of 3 (range 1-6, P = 0.16). However, applicants were asked to indicate, for their first five ranked programs, whether they had been in-person or virtual interviews. For all five positions on the list, the majority of applicants ranked programs where they participated in in-person interviews (57%-88%).

Discussion

All applicants who responded to this survey had interviews impacted by COVID-19, with some interviews that were converted to a virtual format or interviews that were canceled or rescheduled. Both faculty and applicants expressed that in-person interviews were preferred over virtual interviews, and applicants did not feel that they were able to get to know the program as well when participating in a virtual interview. Applicants and faculty agreed that virtual interviews could potentially be used in the future as a screening tool but were less likely to recommend them as a complete replacement or an option. Finally, applicants were more likely to report that interview type influenced their final rank list.

The Pediatric Surgery community has considered, but not widely implemented, alternative approaches to the standard interview process in the past. These results are consistent with the only previous study looking at virtual interviews in Pediatric Surgery. Chandler et al. found that both applicants and faculty did not think virtual interviews could replace in-person interviews but could instead be used as a screening tool.8 Other studies have been published examining at virtual interviews for other specialties. One study looking at Gastroenterology fellowship interviews also found that most applicants felt virtual interviews should not completely replace the in-person interviews.10 When questioned, applicants cited concerns about inability to see the city, inability to gain detailed knowledge about the program, and inability to interact more with faculty and fellows as drawbacks to virtual interviews.10 Family Medicine faculty and applicants also felt that virtual interviews could not replace in-person interviews,11 and a separate study found that 19% of applicants were not even comfortable ranking a program after a virtual interview.12

These results raise concerns about the potential future use of virtual interviews. The Coalition of Physician Accountability, which includes the Association of American Medical Colleges, National Resident Matching Program, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and American Medical Association, among others, has released a statement recommending all programs conduct virtual interviews in lieu of in-person interviews for the 2021-2022 interview cycle. However, most faculty and applicants in this study and others did not recommend virtual interviews as a complete replacement for in-person interviews. Unfortunately, COVID-19, or future large-scale interruptions, may necessitate that programs carry on with virtual interviews this season. Several studies have shown that interviews significantly affect a program's final rank list, with most applicants’ position on the rank list changing five positions after interviews.4 , 8 Programs should strive to keep in mind that applicants may not get the same experience during virtual interviews to fully get to know the program and integrate the use of videos or innovate new ideas to help with this concern. Virtual social events have been suggested as a way for applicants to learn more about informal elements of a program in lieu of in-person social events.13 These types of events may help alleviate the concerns many individuals have regarding virtual interviews.

There were several limitations to this survey. Most importantly was the low response rate in applicants. Because of competing clinical demands, often accumulated over time due to missed calls during the interview season, and because of the rapidly evolving COVID-19 pandemic, we expected a low response rate from the applicants. An additional limiting factor in response rates may be survey fatigue from numerous COVID-19–related surveys. This limits the generalizability of results and conclusions able to be drawn from this study. However, as our results were in-line with those seen in prior surveys of fellowship and residency applicants before the COVID-19 pandemic, we feel they are still valid. In addition, the survey was limited to applicants who applied to a particular fellowship program and its faculty and may therefore not be generalizable across all programs. This represents a very small sample size and we hope larger, more broad studies will be completed this interview season. A larger scale study across all fellowship programs and over multiple years of data may prove informative. It should also be noted that all applicants had previously participated in in-person residency interviews and participated in in-person fellowship interviews before the start of COVID-19. They therefore could directly compare their own experiences to form conclusions. Finally, survey studies in general are vulnerable to recall bias, ascertainment bias, and data reliability.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in many challenges in surgical education, including the interview process for fellowships. Pediatric Surgery interviews were forced to convert to virtual formats due to the spread of pandemic. Faculty and applicants who participated in these interviews and participated in this pilot study did not recommend that virtual interviews replace in-person interviews in the future, with applicants reporting that they did not feel they got to know the programs as well through virtual interviews and that interview type had an effect on their final rank list. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, more virtual interviews will be necessary, and innovations may be necessary to ensure an optimal interview process.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Lauren Camp for her assistance with study coordination and Dr. Eunice Huang for her assistance in survey design.

Author’s contributions: RL and AG contributed to conception and design of the study. RL contributed to acquisition of data. All authors contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, drafting/revision the article, and final approval.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.09.029.

Disclosure

The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Dr. Gosain is an Associate Editor for the Journal of Surgical Research; as such, he was excluded from the entire peer-review and editorial process for this manuscript.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Borman K.R., Vick L.R., Biester T.W., Mitchell M.E. Changing demographics of residents choosing fellowships: longterm data from the American Board of Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.012. [discussion 788-789] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yheulon C.G., Cole W.C., Ernat J.J., Davis S.S., Jr. Normalized competitive index: analyzing trends in surgical fellowship training over the past decade (2009-2018) J Surg Educ. 2020;77:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savoie K.B., Kulaylat A.N., Huntington J.T., et al. The pediatric surgery match by the numbers: defining the successful application. J Pediatr Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downard C.D., Goldin A., Garrison M.M., Waldhausen J., Langham M., Hirschl R. Utility of onsite interviews in the pediatric surgery match. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1042–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gadepalli S.K., Downard C.D., Thatch K.A., et al. The effort and outcomes of the Pediatric Surgery match process: are we interviewing too many? J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1954–1957. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Resident Matching Program . Data Release and Research Committee: Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey, Specialties Matching Service. Program NRM.; Washington, DC: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson S.L., Hollis R.H., Oladeji L., Xu S., Porterfield J.R., Ponce B.A. The burden of the fellowship interview process on general surgery residents and programs. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandler N.M., Litz C.N., Chang H.L., Danielson P.D. Efficacy of videoconference interviews in the pediatric surgery match. J Surg Educ. 2019;76:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little D.C., Yoder S.M., Grikscheit T.C., et al. Cost considerations and applicant characteristics for the pediatric surgery match. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.09.013. [discussion 73-64] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daram S.R., Wu R., Tang S.J. Interview from anywhere: feasibility and utility of web-based videoconference interviews in the gastroenterology fellowship selection process. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:155–159. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edje L., Miller C., Kiefer J., Oram D. Using skype as an alternative for residency selection interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:503–505. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00152.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healy W.L., Bedair H. Videoconference interviews for an adult reconstruction fellowship: lessons learned. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:e114. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKinley S.K., Fong Z.V., Udelsman B., Rickert C.G. Successful virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e192. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.