Abstract

O157 Escherichia coli is one of the most important foodborne pathogens causing disease even at low cellular numbers. Thus, the early and accurate detection of this pathogen is important. However, due to the formation of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) status, the golden standard culturing methodology fails to identify O157 E. coli once it enters VBNC status. Crossing priming amplification (CPA) is a novel, simple, easy-to-operate detection technology that amplifies DNA with high speed, efficiency, and specificity under isothermal conditions. The objective of this study was to firstly develop and apply a CPA assay with propidium monoazide (PMA) for the rapid detection of the foodborne E. coli O157:H7 in VBNC state. Five primers (2a/1s, 2a, 3a, 4s, and 5a) were specially designed for recognizing three targets, which were rfbE, stx1, and stx2, and evaluated for its effectiveness in detecting VBNC cell of E. coli O157:H7 with detection limits of pure VBNC culture at 103, 105, and 105 colony-forming units (CFUs)/ml for rfbE, stx1, and stx2, respectively, whereas those of food samples (frozen pastry and steamed bread) were 103, 105, and 105 CFUs/ml. The application of the PMA-CPA assay was successfully used on detecting E. coli O157:H7 in VBNC state from food samples. In conclusion, this is the first development of PMA-CPA assay on the detection of VBNC cell, which was found to be useful and a powerful tool for the rapid detection of E. coli O157:H7 in VBNC state. Undoubtedly, the PMA-CPA method can be of high value to the food industry owing to its various advantages such as speed, specificity, sensitivity, and cost-effectiveness.

Keywords: propidium monoazide-crossing priming amplification, viable but non-culturable state, Escherichia coli O157:H7, rapid detection, foodborne pathogens

Highlights

-

-

This is the first development of a PMA-CPA method on VBNC detection.

-

-

This detection assay has been successfully applied to three targets of Escherichia coli in VBNC state.

-

-

This study proposes the necessity for viable cell detection instead of the conventional “golden standard” culturing methodology.

Introduction

In recent years, the outbreak of foodborne diseases caused by pathogens and its related virulence factors is a major threat for many countries, although much attention had been paid to food safety issues. Foodborne pathogens including enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have posed great concern in the food industry and public health (Miao et al., 2016, 2019; Xie et al., 2017a; Xu et al., 2019), especially their acquisition of antimicrobial resistance (Xu et al., 2007, 2011a, 2017b; Yu et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2017b; Liu et al., 2018c,d), biofilm formation (Lin et al., 2016; Bao et al., 2017a; Miao et al., 2017b), and toxin production (Liu et al., 2016a). EHEC causes more than 63,000 illnesses, 2,100 hospitalizations, and 20 deaths each year in the United States (Jiang et al., 2016). E. coli O157:H7 is the main EHEC serotype that causes the majority of EHEC human infections. As one of the most commonly found foodborne pathogens, it can be transmitted by contaminated food such as cattle, milk, eggs and vegetables, rice cakes, and others (Ackers et al., 1998; Jacob et al., 2013; Marder et al., 2014). The methods are labor-intensive and time-consuming and cannot meet the requirement of rapid monitoring. Hence, developing a rapid, sensitive, and accurate method to detect E. coli O157:H7 in various foods with a complex matrix is crucial in preventing disastrous E. coli O157:H7 outbreaks and associated human infections.

In 1982, Xu et al. (1982) firstly reported “viable but non-culturable” (VBNC) state, which was considered to be a survival strategy of non-spore-forming bacteria in response to adverse conditions (Xu et al., 1982; Oliver, 2010). Bacteria can enter into VBNC state by the stimulation of adverse environmental conditions, such as low temperature, nutrient-limited conditions, high salt, low pH, and even ultraviolet-induced (Foster, 1999; Ramaiah et al., 2002; Cunningham et al., 2009; Deng et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017a,b, 2018a,b; Guo et al., 2019). For now, 85 species of bacteria have been confirmed that can enter into VBNC state, including 18 non-pathogenic and 67 pathogenic species (Li et al., 2014). In recent years, many studies have determined that VBNC bacteria still can produce harmful substances (Deng et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017a,b, 2018a,b). Shigella dysenteriae and E. coli O157 still retain Shiga toxin encoding gene (stx) and produce toxin in VBNC state (Rahman et al., 1996; Liu et al., 2017d). Moreover, bacteria in VBNC can resuscitate and grow again with suitable conditions (Pinto et al., 2015). Nowadays, the traditional culture method and a nucleic acid detection method are widely used. However, the discovery of VBNC in recent years has brought difficulties to the detection method. The VBNC cell cannot grow on the plate medium due to low metabolic activity, which means that normal culture methods can lead to false-negative results of detection. Hence, rapid and accurate identification of VBNC bacteria is of utmost importance. Bacteria in the VBNC state remain metabolically and physiologically viable and continuing to express virulence genes (Liu et al., 2016b, c, d, 2017a, 2017c,2018a; Bao et al., 2017b; Xu et al., 2017a). Concerning conventional detection methods that are time-consuming and only suitable for experimental use, alternative rapid and cost-effective detection methods are desperately required to detect VBNC pathogens (Lin et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016; Miao et al., 2017a; Zhao et al., 2018). As the ethidium bromide monoazide (EMA) or propidium monoazide (PMA) penetrates only into dead bacterial cells with compromised membrane integrity but not into live cells with intact cell membranes, EMA/PMA treatment to cultures with both viable and dead cells results in selective removal of DNA from dead cells. Therefore, scientists had utilized EMA/PMA combined with nucleic acid amplification techniques to complete the detection of VBNC cells. Recently, nucleic acid amplification methods combined with EMA/PMA have been widely used for the detection of pathogenic bacteria in the VBNC state, such as PMA-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Liu Y. et al., 2018; Zhong and Zhao, 2018).

Although numerous quick methods based on nucleic acids, such as PCR (Gehring and Tu, 2005; Xu et al., 2011b) and real-time PCR (O’Hanlon et al., 2004), have been developed and used for detecting E. coli O157:H7 in food, a quicker and less expensive technology is always most preferred. Isothermal amplification is a novel method for DNA amplification at a constant temperature, providing simple, fast, independent of sophisticated instruments and cost-effective techniques to detect biological targets, especially for less well-equipped laboratories, as well as for filed detection. Isothermal technologies mainly include loop-mediated isothermal amplification, rolling circle amplification, single primer isothermal amplification, polymerase spiral reaction, strand displacement amplification, and recombinase polymerase amplification (Walker et al., 1992; Notomi et al., 2000; Haible et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2009, 2010, 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Xu Z. et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017). Cross priming amplification (CPA) is a novel isothermal method that relies on five primers (2a/1s, 2a, 3a, 4s, and 5a) to amply the target nucleotide sequences (Xu G. et al., 2012). It does not require any special instrumentation and presents all the features, including rapidity, specificity, and sensitivity. Recently, CPA assays have been used for the detection of E. coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, Enterobacter sakazakii, Salmonella enterica, Yersinia enterocolitica, and other pathogens (Yulong et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014, 2018; Zhang et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2020). Introducing the cross-priming principles, CPA is advantageous on reproducibility and stability with a similar level of sensitivity, specificity, and rapidity comparing with loop-mediated isothermal amplification, the most broadly applied isothermal methodologies. Therefore, CPA is a potentially valuable tool for the rapid diagnosis of foodborne pathogens, as well as those in the VBNC state. However, there is no report of PMA-CPA assay for the detection of VBNC E. coli O157:H7.

This study aimed to develop a rapid PMA-CPA assay to detect E. coli O157:H7 in VBNC state targeting on rfbE, stx1, and stx2 genes combining visual methods with the addition of calcein and applying this assay to detect the E. coli O157:H7 strains from food samples.

Materials and Methods

Induction of Entry Into the Viable But Non-culturable State in Saline and Food Sample

Induction of VBNC cells and the establishment of PMA-CPA assays were performed on E. coli O157 ATCC43895. The bacterial strain was incubated in trypticase soy broth (Huankai Microbial, China) to reach the exponential phase [∼109 colony-forming units (CFUs)/ml]. To induce the entry of VBNC state, the culture was diluted to the final density of 108 CFU/ml with saline (pure culture system) and food homogenate (Cantonese rice cake, Guangzhou Restaurant, Guangzhou) (food system) and stored at −20°C.

Determination of the Culturable and Viable But Non-culturable State of E. coli O157

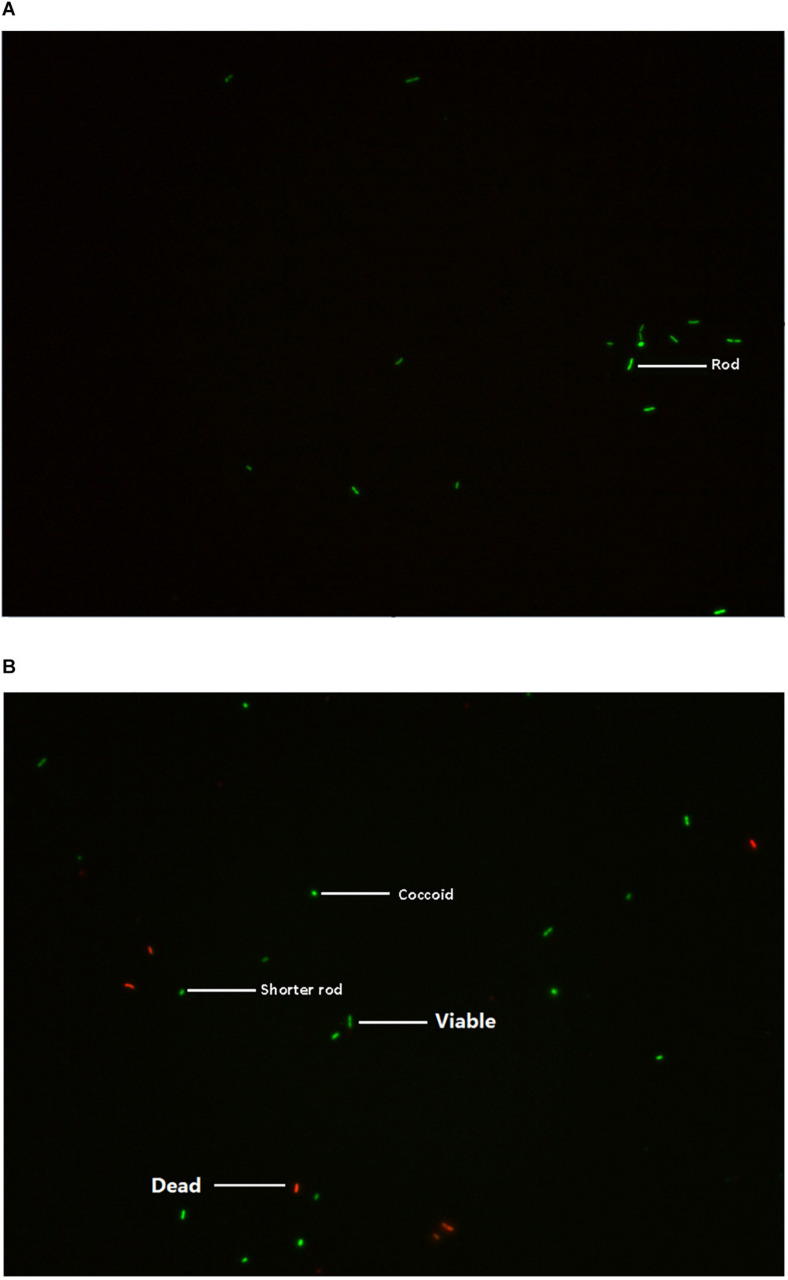

The conventional plate counting method was used to determine the cultivability of E. coli O157. The induction culture was serial diluted with 0.9% sodium chloride and inoculated on trypticase soy agar at 37°C for 24 h. When the number of colonies was <1 CFU/ml for 3 days, it was considered that the survived cells might have entered into the non-culturable state (Deng et al., 2015). Also, the final determination of the VBNC cell was evaluated by the LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, China) (Liu et al., 2017d). The stained induction culture was observed by fluorescence microscopy.

Design of Crossing Priming Amplification Primers

As mentioned before (Xu et al., 2020), the CPA primers were designed for specific O-antigen rfbE gene and Shiga toxin genes stx1 and stx2 of E. coli via Primer Premier 5. For each of the target genes, a set of primers were designed, including five primers that recognized five distinct regions on corresponding sequences. Primers used in this study have been enumerated in Tables 1, 2. All primers were assessed for specificity before use in CPA assays by doing a Blast search with a sequence in GenBank1.

TABLE 1.

Reference strains and results of CPA assays.

| Reference strains | PCR assays | CPA results | |||||

| Gram-negative organisms | No. of strains | rfbE | stx1 | stx2 | rfbE | stx1 | stx2 |

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 ATCC43895 | 1 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

TABLE 2.

Primers sequence for detection.

| Target gene | Primers | Sequence (5′-3′) |

| rfbE | 4s | AGGACCGCAGAGGAAAGA |

| 5a | TCCACGCCAACCAAGATC | |

| 2a/1s | AGTACATTGGCATCGTGTCAGATAAACTCATCGAAACA | |

| 2a | AGTACATTGGCATCGTGT | |

| 3a | GGCATCGTGTGGACAGGGT | |

| stx1 | 4s | AGTTGATGTCAGAGGGATAG |

| 5a | CGCTGTTGTACCTGGAAA | |

| 2a/1s | ATCAGCAAAGCGATAAAACTACGGCTTATTGTTGAA | |

| 2a | ATCAGCAAAGCGATAAAA | |

| 3a | CCTGTTAACAAATCCTGTCAC | |

| stx2 | 4s | GTTACGGGAAGGAATCAGG |

| 5a | AAATCAGCCACCCACAGC | |

| 2a/1s | CGAACTGACGGTTTACGCATGGGACTTGCCGGTGTT | |

| 2a | CGAACTGACGGTTTACGC | |

| 3a | TGGTCGTACGGACCTTTT |

Development of Propidium Monoazide-Crossing Priming Amplification Assay in Pure Bacterial Culture and Food Sample

For the pure bacterial culture, 500 μl of 10–106-CFU/ml VBNC culture was transformed into 1.5-ml centrifuge tubes. For the food sample culture, the 10–106-CFU/ml cultures were washed three times by saline to avoid the effect of substances in a food sample and placed in 1.5-ml centrifuge tubes. Then, PMA reagent was added to the final concentration of 5 μg/ml. Subsequently, the detection samples mixed with PMA were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 min before the tubes were placed horizontally on ice exposed to a halogen lamp (650 W) at a distance of 15 cm for 15 min to complete the combination of DNA and PMA (Chen et al., 2020). The mixed samples were centrifuged at 10,000 r/min for 5 min, and the precipitation under the tubes was processed by DNA extraction kit (Dongsheng Biotech, Guangzhou) followed the instruction of the manufacturer, which were prepared as DNA samples for PMA-CPA.

The CPA reaction was performed as mentioned before (Xu et al., 2020), using thermostatic equipment or water bath in 26 μl, which contained 20-mM Tris–HCl, 10-mM (NH4)2SO4, 10-mM KCl, 8.0-mM MgSO4, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.7-M betaine (Sigma), 1.4-mM dNTP (each), 8-U Bst DNA polymerase (NEB, United States), a 1.0-μM primer of 2a/1s, a 0.5-μM (each) primer of 2a and 3a, 0.6-μM (each) primer of 4s and 5a, 1-μl mixture chromogenic agent (mixture with calcein and Mn2+), and 1-μl template DNA, and the volume was made up to 26 μl with nuclease-free water. The mixed chromogenic agent consists of 0.13-mM calcein and 15.6-mM MnCl2.4H2O.

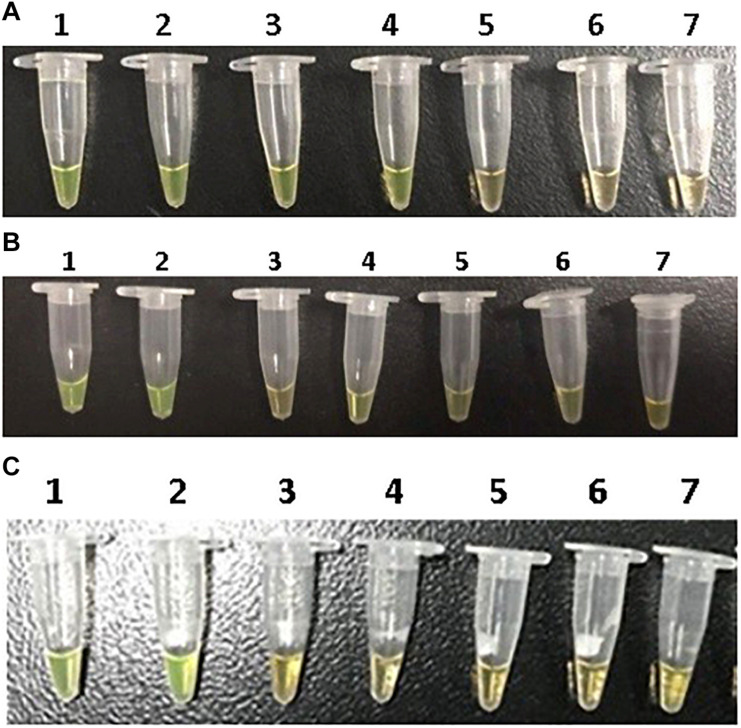

The mixed reaction solution was incubated at 65°C for 60 min and heated at 80°C for 2 min to terminate it. PMA-CPA amplified products were visualized under visible light or the appearance of the laddering pattern on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. However, instead of the laddering pattern, apparent bright strip might present, which can also be regarded as positive results. This experiment was performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

Results

Observation of E. coli O157 in Viable But Non-culturable State With Fluorescence Microscopy

The E. coli O157 in normal viable and VBNC state was analyzed using the LIVE/DEAD® BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit. Under a fluorescence microscope, the VBNC cells showed green, whereas dead cells exhibited red (Figure 1). The results showed that the VBNC cell might change their morphological characterization from rod-shaped (normal state) to shorter rods or coccoid (VBNC state) (Liu et al., 2017c).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of E. coli O157 in normal viable (A) and VBNC state (B) under fluorescence microscopy.

Propidium Monoazide-Crossing Priming Amplification Assay for Detection of Viable But Non-culturable Cells of E. coli O157 in Food Samples

Serial diluted DNA of VBNC cells evaluated the sensitivity of PMA-CPA. There was an obvious color change at the 103–106 CFU/ml DNA, and the ladder-like pattern was clearly observed under ultraviolet light. The detection limits of E. coli O157 VBNC were 103, 105, and 105 CFU/ml for rfbE, stx1, and stx2 genes, respectively.

The PMA-CPA assays for the detection of E. coli O157 VBNC in food samples were successfully conducted. The detection limits of VBNC cells in the food system were 103, 105, and 105 CFU/ml for rfbE, stx1, and stx2 genes, respectively, which were the same as the limits in pure VBNC cells (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Sensitivity of PMA-CPA assay for detection of VBNC cells of rfbE (A), stx1 (B), and stx2 (C) genes by mixed chromogenic agent in food samples. M-DNA marker; lanes 1–7, 106, 105, 104, 103, 102, and 10 CFU/ml, negative control.

Discussion

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is currently a widespread foodborne pathogen throughout the world and has promoted a heightened interest and concern for the low-level detection of these foodborne pathogens (Pennington, 2010). There is a fast-increasing and urgent demand for high-performance techniques for monitoring bacteria in complex foods to reduce the risk of the associated food poisoning. In evaluating detection methodologies for ecologic and epidemiological purposes, a series of attributes should be considered and assessed, including specificity, sensitivity, simplicity, expense, and time. In this study, PMA-CPA assay targeting rfbE, stx1, and stx2 successfully detected detection E. coli O157:H7 VBNC cell in pure culture and food samples. Notably, Shiga toxins 1 and 2 (Stx1 and Stx2) encoded by stx1 and stx2 can result in gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea and hemorrhagic colitis, and may also progress to a hemolytic uremic syndrome, a severe sequela of this infection (Saeedi et al., 2017). Considered to be an important health risk in the food testing, the detection of Shiga toxin, especially rapid and easy operating detection assay, may be of utmost significance and urgent necessity. Therefore, we established a PMA-CPA method for the detection of E. coli O157:H7 in VBNC cell, as well as its virulence factors. The detection limits of PMA-CPA assay showed consistency with that of CPA assay, no matter in pure bacterial culture or food samples, which had been performed previously (Xu et al., 2020). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a PMA-CPA assay to detect E. coli O157:H7 in VBNC state from food samples.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the designed CPA primers targeted the rfbE, stx1, and stx2 genes for the effective detection of E. coli O157:H7 VBNC cell. Therefore, being simple, rapid, sensitive, and specific, PMA-CPA assay can be a useful and powerful method in the field and also an alternative diagnostic tool for the detection of E. coli O157:H7 in VBNC cell and its related virulence factors in testing as part of an outbreak investigation.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (2017A030310419), Characteristic Innovation Projects of Universities in Guangdong Province (2019KTSCX13), 2019 Laboratory Opening Project of Guangzhou Medical University (201910570001), and 111 Project (B17018).

References

- Ackers M. L., Mahon B. E., Leahy E., Goode B., Damrow T., Hayes P. S., et al. (1998). An outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections associated with leaf lettuce consumption. J. Infect. Dis. 177 1588–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X., Jia X., Chen L., Peters B. M., Lin C., Chen D., et al. (2017a). Effect of Polymyxin Resistance (pmr) on Biofilm Formation of Cronobacter sakazakii. Microb. Pathogen. 106 16–19. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X., Yang L., Chen L., Li B., Li L., Li Y., et al. (2017b). Analysis on pathogenic and virulent characteristics of the Cronobacter sakazakii strain BAA-894 by whole genome sequencing and its demonstration in basic biology science. Microb. Pathogen. 109 280–286. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhong C., Zhang T., Shu M., Lin L., Luo Q., et al. (2020). Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Viable but Non-culturable Salmonella Induced by Low Temperature from Chicken Using EMA-Rti-LAMP Combined with BCAC. Food Analy. Methods 13 313–324. 10.1007/s12161-019-01655-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham E., O’Byrne C., Oliver J. D. (2009). Effect of weak acids on Listeria monocytogenes survival: Evidence for a viable but nonculturable state in response to low pH. Food Contr. 20 1141–1144. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2009.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Liu J., Li L., Fang H., Tu J., Li B., et al. (2015). Reduction and restoration of culturability of beer-stressed and low-temperature-stressed Lactobacillus acetotolerans strain 2011-8. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 206 96–101. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. W. (1999). When protons attack: microbial strategies of acid adaptation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2 170–174. 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80030-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring A. G., Tu S. I. (2005). Enzyme-linked immunomagnetic electrochemical detection of live Escherichia coli 0157:H7 in apple juice. J. Food Prot. 68 146–149. 10.4315/0362-028x-68.1.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Ye C., Cui L., Wan K., Chen S., Zhang S., et al. (2019). Population and single cell metabolic activity of UV-induced VBNC bacteria determined by CTC-FCM and D(2)O-labeled Raman spectroscopy. Environ. Int. 130:104883. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.05.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haible D., Kober S., Jeske H. (2006). Rolling circle amplification revolutionizes diagnosis and genomics of geminiviruses. J. Virol. Methods 135 9–16. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob M. E., Foster D. M., Rogers A. T., Balcomb C. C., Shi X., Nagaraja T. G. (2013). Evidence of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in the feces of meat goats at a U.S. slaughter plant. J. Food Prot. 76 1626–1629. 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-13-064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Song Y., Wei T., Li H., Du D., Zhu M. J., et al. (2016). Sensitive detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 using Pt-Au bimetal nanoparticles with peroxidase-like amplification. Biosens Bioelectron 77 687–694. 10.1016/j.bios.2015.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Mendis N., Trigui H., Oliver J. D., Faucher S. P. (2014). The importance of the viable but non-culturable state in human bacterial pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 5:258. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S., Li L., Li B., Zhao X., Lin C., Deng Y., et al. (2016). Development and evaluation of quantitative detection of N-epsilon-carboxymethyl-lysine in Staphylococcus aureus biofilm by LC-MS method. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 118:33 10.1007/978-1-4614-3828-1_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Chen D., Peters B. M., Li L., Li B., Xu Z., et al. (2016a). Staphylococcal chromosomal cassettes mec (SCCmec): A mobile genetic element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Pathogen. 101 56–67. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Deng Y., Peters B. M., Li L., Li B., Chen L., et al. (2016b). Transcriptomic analysis on the formation of the viable putative non-culturable state of beer-spoilage Lactobacillus acetotolerans. Sci. Rep. 6:36753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Ji L., Peters B. M., Li L., Li B., Duan J., et al. (2016c). Whole genome sequence of two Bacillus cereus strains isolated from soy sauce residues. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 118:34. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Li L., Peters B. M., Li B., Deng Y., Xu Z., et al. (2016d). Draft genome sequence and annotation of Lactobacillus acetotolerans BM-LA14527, a beer-spoilage bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 363:fnw201. 10.1093/femsle/fnw201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Deng Y., Li L., Li B., Li Y., Zhou S., et al. (2018a). Discovery and control of culturable and viable but non-culturable cells of a distinctive Lactobacillus harbinensis strain from spoiled beer. Sci. Rep. 8:11446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Deng Y., Soteyome T., Li Y., Su J., Li L., et al. (2018b). Induction and recovery of the viable but nonculturable state of hop-resistance Lactobacillus brevis. Front. Microbiol. 9:2076. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Xie J., Yang L., Chen D., Peters B. M., Xu Z., et al. (2018c). Identification of the KPC plasmid pCT-KPC334: new insights on the evolution pathway of the epidemic plasmids harboring fosA3-blaKPC-2 genes. Int. J. Antimicrob. Ag. 52 510–512. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Yang L., Chen D., Peters B. M., Li L., Li B., et al. (2018d). Complete sequence of pBM413, a novel multi-drug-resistance megaplasmid carrying qnrVC6 and blaIMP-45 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Antimicrob. Ag. 51 145–150. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Li L., Li B., Peters B. M., Deng Y., Xu Z., et al. (2017a). Study on spoilage capability and VBNC state formation and recovery of Lactobacillus plantarum. Microb. Pathogen. 110 257–261. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Li L., Li B., Peters B. M., Xu Z., Shirtliff M. E. (2017b). First study on the formation and resuscitation of viable but nonculturable state and beer spoilage capability of Lactobacillus lindneri. Microb. Pathogen. 107 219–224. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Li L., Peters B. M., Li B., Chen D., Xu Z., et al. (2017c). Complete genome sequence and bioinformatics analyses of Bacillus thuringiensis strain BM-BT15426. Microb. Pathogen. 108 55–60. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zhou R., Li L., Peters B. M., Li B., Lin C. W., et al. (2017d). Viable but non-culturable state and toxin gene expression of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 under cryopreservation. Res. Microbiol. 168 188–193. 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Dong D., Yang Z., Zou D., Chen Z., Yuan J., et al. (2015). Polymerase Spiral Reaction (PSR): A novel isothermal nucleic acid amplification method. Sci. Rep. 5:12723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Liu Y., Zhong Q., Wang J., Lei S. (2018). Enumeration of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in VBNC state by PMA-combined real-time quantitative PCR coupled with confirmation of respiratory activity. Food Contr. 91 85–91. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.03.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E. P., Garman K. N., Ingram L. A., Dunn J. R. (2014). Multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with bagged salad. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 11 593–595. 10.1089/fpd.2013.1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J., Chen L., Wang J., Wang W., Chen D., Li L., et al. (2017a). Current methodologies on genotyping for nosocomial pathogen methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Microb. Pathogen. 107 17–28. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J., Liang Y., Chen L., Wang W., Wang J., Li B., et al. (2017b). Formation and development of Staphylococcus biofilm: With focus on food safety. J. Food Safety 7:e12358. [Google Scholar]

- Miao J., Lin S., Soteyome T., Peters B. M., Li Y., Chen H., et al. (2019). Biofilm Formation of Staphylococcus aureus under Food Heat Processing Conditions-First Report on CML Production within Biofilm. Sci. Rep. 9:1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J., Peters B. M., Li L., Li B., Zhao X., Xu Z., et al. (2016). “Evaluation of ERIC-PCR for Fingerprinting Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains,” in The 5th International Conference on Biotechnology and Bioengineering, (Hyderabad: Scientific Federation; ). [Google Scholar]

- Notomi T., Okayama H., Masubuchi H., Yonekawa T., Watanabe K., Amino N., et al. (2000). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hanlon K. A., Catarame T. M., Duffy G., Blair I. S., McDowell D. A. (2004). RAPID detection and quantification of E. coli O157/O26/O111 in minced beef by real-time PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 96 1013–1023. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J. D. (2010). Recent findings on the viable but nonculturable state in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34 415–425. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00200.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington H. (2010). Escherichia coli O157. Lancet 376 1428–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D., Santos M. A., Chambel L. (2015). Thirty years of viable but nonculturable state research: unsolved molecular mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 41 61–76. 10.3109/1040841x.2013.794127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman I., Shahamat M., Chowdhury M. A., Colwell R. R. (1996). Potential virulence of viable but nonculturable Shigella dysenteriae type 1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62 115–120. 10.1128/aem.62.1.115-120.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaiah N., Ravel J., Straube W. L., Hill R. T., Colwell R. R. (2002). Entry of Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio fischeri into the viable but nonculturable state. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeedi P., Yazdanparast M., Behzadi E., Salmanian A. H., Mousavi S. L., Nazarian S., et al. (2017). A review on strategies for decreasing E. coli O157:H7 risk in animals. Microb. Pathog. 103 186–195. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker G. T., Fraiser M. S., Schram J. L., Little M. C., Nadeau J. G., Malinowski D. P. (1992). Strand displacement amplification–an isothermal, in vitro DNA amplification technique. Nucleic Acids Res. 20 1691–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Zhao X., Chu J., Li Y., Li Y., Li C., et al. (2011). Application of an improved loop-mediated isothermal amplification detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus from various seafood samples. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 5 5765–5771. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang Y., Ma A., Li D., Ye C. (2014). Rapid and sensitive detection of Listeria monocytogenes by cross-priming amplification of lmo0733 gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 361 43–51. 10.1111/1574-6968.12610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. X., Zhang A. Y., Yang Y. Q., Lei C. W., Cheng G. Y., Zou W. C., et al. (2018). Sensitive and rapid detection of Salmonella enterica serovar Indiana by cross-priming amplification. J. Microbiol. Methods 153 24–30. 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Peters B. M., Li B., Li L., Yu G., Xu Z., et al. (2017a). Clinical features and antimicrobial resistance profiles of important Enterobacteriaceae pathogens in Guangzhou representative of Southern China, 2001-2015. Microb. Pathogen. 107 206–211. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Yang L., Peters B. M., Chen L., Chen D., Li B., et al. (2017b). A 16-year retrospective surveillance report on the pathogenic features and antimicrobial susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from Guangzhou representative of Southern China. Microb. Pathogen. 110 37–41. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G., Hu L., Zhong H., Wang H., Yusa S., Weiss T. C., et al. (2012). Cross priming amplification: mechanism and optimization for isothermal DNA amplification. Sci. Rep. 2:246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. S., Roberts N., Singleton F. L., Attwell R. W., Grimes D. J., Colwell R. R. (1982). Survival and viability of nonculturableEscherichia coli andVibrio cholerae in the estuarine and marine environment. Microb. Ecol. 8 313–323. 10.1007/bf02010671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Hou Y., Qin D., Liu X., Li B., Li L., et al. (2016). “Evaluation of current methodologies for rapid identification of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus strains,” in in The 5th International Conference on Biotechnology and Bioengineering, (China: South China University of Technology; ). [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Li L., Chu J., Peters B. M., Harris M. L., Li B., et al. (2012). Development and application of loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays on rapid detection of various types of staphylococci strains. Food Res. Int. 47 166–173. 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Li L., Shi L., Shirliff M. E. (2011a). Class 1 integron in staphylococci. Mol. Biol. Rep. 38 5261–5279. 10.1007/s11033-011-0676-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Li L., Zhao X., Chu J., Li B., Shi L., et al. (2011b). Development and application of a novel multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for rapid detection of various types of staphylococci strains. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 5 1869–1873. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Luo Y., Soteyome T., Lin C.-W., Xu X., Mao Y., et al. (2020). Rapid Detection of Food-Borne Escherichia coli O157:H7 with Visual Inspection by Crossing Priming Amplification (CPA). Food Analy. Methods 13 474–481. 10.1007/s12161-019-01651-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Shi L., Zhang C., Zhang L., Li X., Cao Y., et al. (2007). Nosocomial infection caused by class 1 integron-carrying Staphylococcus aureus in a hospital in South China. Clin. Microbiol. Infec. 13 980–984. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01782.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Xie J., Liu J., Ji L., Soteyome T., Peters B. M., et al. (2017a). Whole-genome resequencing of Bacillus cereus and expression of genes functioning in sodium chloride stress. Microb. Pathogen. 104 248–253. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Xie J., Peters B. M., Li B., Li L., Yu G., et al. (2017b). Longitudinal Surveillance on Antibiogram of Important Gram-positive Pathogens in Southern China, 2001 to 2015. Microb. Pathogen. 103 80–86. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Xie J., Soteyome T., Peters B. M., Shirtliff M. E., Liu J., et al. (2019). Polymicrobial interaction and biofilms between Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: an underestimated concern in food safety. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 26 57–64. 10.1016/j.cofs.2019.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Yang Q., Ma X., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Zhang W. (2017). A novel developed method based on single primer isothermal amplification for rapid detection of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris in apple juice. Food Control. 75 187–195. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G., Wen W., Peters B. M., Liu J., Ye C., Che Y., et al. (2016). First report of novel genetic array aacA4-bla(IMP-25)-oxa30-catB3 and identification of novel metallo-beta-lactamase gene bla(IMP25): A Retrospective Study of antibiotic resistance surveillance on Psuedomonas aeruginosa in Guangzhou of South China, 2003-2007. Microb. Pathogen. 95 62–67. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yulong Z., Xia Z., Hongwei Z., Wei L., Wenjie Z., Xitai H. (2010). Rapid and sensitive detection of Enterobacter sakazakii by cross-priming amplification combined with immuno-blotting analysis. Mol. Cell Probes. 24 396–400. 10.1016/j.mcp.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Feng S., Zhao Y., Wang S., Lu X. (2015). Detection of Yersinia enterocolitica in milk powders by cross-priming amplification combined with immunoblotting analysis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 214 77–82. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Li M., Xu Z. (2018). Detection of Foodborne Pathogens by Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Front. Microbiol. 9:1236. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Li W., Li Y., Xu Z., Li L., He X., et al. (2011). Development and application of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method on rapid detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. World J. Microb. Biot. 27 181–184. 10.1007/s11274-010-0429-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Li Y., Chu J., Wang L., Shirtliff M. E., He X., et al. (2010). Rapid detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains and virulent factors by loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 19 1191–1197. 10.1007/s10068-010-0170-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Wang L., Chu J., Li Y., Li Y., Xu Z., et al. (2009). Development and application of a rapid and simple loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for food-borne Salmonella detection. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 19 1655–1659. 10.1007/s10068-010-0234-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J., Zhao X. (2018). Detection of viable but non-culturable Escherichia coli O157:H7 by PCR in combination with propidium monoazide. Biotech 8:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material.