To the editor:

We propose a genetic epidemiologic metric derived from sequencing tumor cells and matched “normal” cells (typically peripheral blood mononuclear cells); this metric can be used to evaluate the relevance of germline pathogenic variants (GPVs) in tumor-suppressor genes to the development of individual cancer types (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). According to Knudson’s two-hit hypothesis, a tumor that is attributable to a GPV requires biallelic inactivation of a tumor-suppressor gene. Biallelic but not monoallelic inactivation of BRCA1 or BRCA2 is accompanied by genomic hallmarks of deficiency in homologous recombination repair.1,2 These genomic hallmarks include mutational signatures (i.e., patterns of somatic nucleotide changes caused by distinct mutagenic processes that can be detected by tumor genome sequencing).1 Therefore, the presence or absence of biallelic inactivation as determined by tumor sequencing can establish whether BRCA1/2 GPVs contributed to the cancer. In a recent study, gene-panel sequencing was used to determine the zygosity status of BRCA1/2 in 17,000 tumors.2 We propose that the fraction of tumors harboring a BRCA1/2 GPV and a second hit (Fig. 1) is the excess risk that can be attributed to the GPV across tumor types.

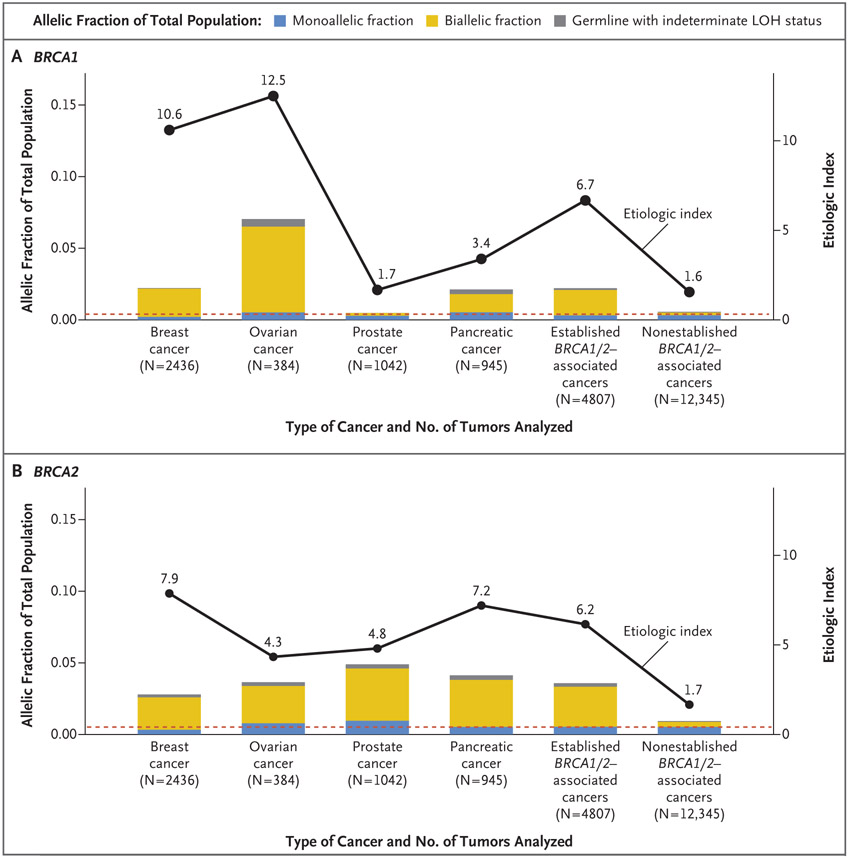

Figure 1. Excess of Risk and the Etiologic Index for BRCA1/2 across Cancer Types.

Shown are the allelic fractions and etiologic indexes for tumors with germline pathogenic variants (GPVs) in BRCA1 (Panel A) and BRCA2 (Panel B). The tumors containing GPVs are categorized into three groups: those without second hits (monoallelic fraction), those accompanied by second somatic hits (biallelic fraction), and those for which, because of technical issues, it is not possible to determine whether the GPVs are accompanied by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) (germline with indeterminate LOH status). The tumors are grouped according to the strength of their association with BRCA1/2 GPVs: breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers are termed “established.” The established group represents the combination of these four tumors, whereas the “nonestablished” group includes all the patients with other tumors in the data set (52 different tumor types). The prevalence of monoallelic status for BRCA1 and BRCA2 in patient tumors is close to the estimated GPV prevalence of 0.0037 for BRCA1 heterozygotes (dashed line in Panel A) and 0.0051 for BRCA2 heterozygotes (dashed line in Panel B). These numbers are based on the weighted average of prevalences: 80% of the alleles occur at a prevalence of 1 in 190 for BRCA1/2 (the prevalence in Pennsylvania),3 with 65% of the GPVs occurring in BRCA2 and 35% in BRCA1, and 20% of the alleles are from the Ashkenazi Jewish population (prevalence of 1 in 40 of BRCA1/2) with the assumption that the GPVs are split evenly between BRCA1 and BRCA2. This weighted average reflects the patient population at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, where the study was performed.2 The etiologic index is defined as the sum of the prevalence of biallelic and monoallelic events divided by the prevalence of monoallelic events. The etiologic indexes derived from this method are close to those estimated from epidemiologic studies.4,5

Jonsson et al.2 found that tumors in breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers that have established associations with BRCA1/2 GPVs (the established set) have a higher fraction of GPVs accompanied by second hits than do other tumors (i.e., the nonestablished set). Established and nonestablished cancers contain monoallelic GPVs that are not etiologically implicated in the disease, as measured by the lack of mutational signatures associated with deficiency in homologous recombination repair (Fig. S1).1 Conversely, some nonestablished tumors with biallelic BRCA1/2 inactivation status have been shown to have such mutation signatures, which implies causal involvement of the GPV in the disease.2

In the fraction of tumors with a GPV but without a second hit (the monoallelic fraction), the GPV does not contribute to disease (Fig. 1). This fraction mirrors the baseline prevalence of GPVs in the population. The relative risk of the association of a cancer type with BRCA1/2 GPVs (the frequency of GPV in cases of cancer vs. the frequency of GPV in the general population) is approximately the ratio of the frequency of GPV in cases of cancer to the frequency in the monoallelic fraction. We call this the “etiologic index” (Fig. 1, and the Supplementary Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix). On the basis of the data provided by Jonsson et al.,2 the BRCA1 etiologic indexes for breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers are 10.6, 12.5, 1.7, and 3.4, respectively (Fig. 1A). The corresponding BRCA2 etiologic indexes are 7.9, 4.3, 4.8, and 7.2 (Fig. 1B).

The BRCA1/2 etiologic index for nonestablished cancers is approximately 1.6, which parallels estimates of relative risks reported in family based genetic studies.4,5 Of note, however, the BRCA1 etiologic index for endometrial cancer is 4.0, and for mesothelioma, we calculated a BRCA2 etiologic index of 4.0 (Fig. S2). More complete details, including 95% confidence intervals, are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. This index could quantify the contribution of GPVs to the development of individual cancer types, with implications for further research, therapeutic choice, and clinical trial design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R35CA220491-03S1, to Mr. Hughley), the National Cancer Institute (cancer center support grant P30CA196521, awarded to the Tisch Cancer Institute of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai to support the Biostatistics Shared Resource Facility, to Dr. Joshi), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-148390, to Dr. Foulkes), and the V Foundation for Cancer Research (to Dr. Polak).

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

Contributor Information

Raymond Hughley, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

Rosa Karlic, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

Himanshu Joshi, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

Clare Turnbull, Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom

William D. Foulkes, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Paz Polak, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

References

- 1.Polak P, Kim J, Braunstein LZ, et al. A mutational signature reveals alterations underlying deficient homologous recombination repair in breast cancer. Nat Genet 2017;49:1476–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonsson P, Bandlamudi C, Cheng ML, et al. Tumour lineage shapes BRCA-mediated phenotypes. Nature 2019;571:576–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manickam K, Buchanan AH, Schwartz MLB, et al. Exome sequencing-based screening for BRCA1/2 expected pathogenic variants among adult biobank participants. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1(5):e182140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson D, Easton DF, the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Cancer incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:1358–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:1310–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.