Abstract

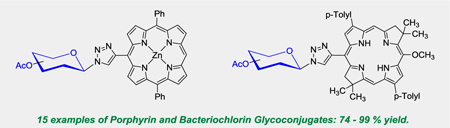

Rapid and reproducible access to a series of unique porphyrin and bacteriochlorin glycoconjugates, including meso-glycosylated porphyrins and bacteriochlorins, and beta-glycosylated porphyrins, via copper catalyzed azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (CuAAC) is reported for the first time. The work presented highlights the system-dependent reaction conditions required for glycosylation to porphyrins and bacteriochlorins based on the unique electronic properties of each ring system. Attenuated reaction conditions were used to synthesize fifteen new glycosylated porphyrin and bacteriochlorin analogs in 74 – 99% yield, and were extended to solid support to produce the first oligo(amidoamine)-based porphyrin glycoconjugate. These compounds hold significant potential as next generation water soluble catalysts and photodynamic therapy/photodynamic inactivation (PDT/PDI) agents.

Keywords: Bacteriochlorin, Cycloaddition, Glycoconjugates, Porphyrinoid

Graphical Abstract

Access to a series of new porphyrin and bacteriochlorin glycoconjugates, including meso-glycosylated porphyrins and bacteriochlorins, and beta-glycosylated porphyrins, via copper catalyzed azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (CuAAC) is reported for the first time.

Introduction

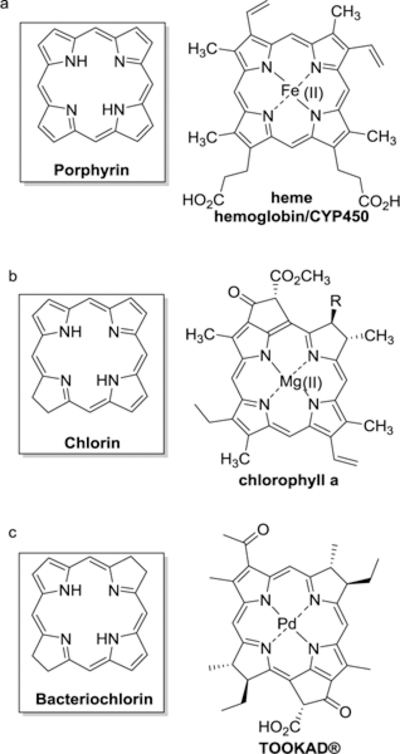

Porphyrins and related macrocycles play essential roles in biological systems including light harvesting, and dioxygen transport. They also facilitate many important biological oxidation reactions.1 For example, the “heme” prosthetic group (an iron-porphyrin complex, Figure 1a) in hemoglobin, plays the central role of oxygen transport in many higher level organisms. The study of heme and the hemoglobin enzyme has led to many reports on the biological role of porphyrins and the search for synthetic oxygen transport systems that can be used for catalysis.2 Similarly, the chlorin macrocycle (Figure 1b), a close relative of the porphyrin, is the essential component of chlorophyll, and has inspired research into utilizing these macrocycles and their derivatives as light harvesting molecules in dye-sensitized solar cells.3 In addition, porphyrins and related macrocycles have gained increasing attention as theranostic agents which combine non-invasive imaging technologies with therapeutic modalities4. In particular, hydroporphyrins, such as the bacteriochlorin TOOKAD®5 (Figure 1c), are gaining importance as next generation theranostic phototherapeutics.6 These compounds, which absorb in the near IR (NIR), are optimal for fluorescence imaging since they allow for deeper tissue penetration and low autofluorescence.7 They are also desirable because they can be used as therapeutic photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy (PDT) and photodynamic inactivation (PDI).

Figure 1.

Basic macrocyclic structure of a porphyrin (a), chlorin (b) and bacteriochlorin (c).

Despite the synthetic advances that have been made towards the use of porphyrins and porphyrin related compounds in the fields of catalysis and PDT/PDI, the hydrophobic character of these macrocycles has restricted their utility in aqueous systems. The conjugation of carbohydrates to these molecules has gained increasing attention as a way to overcome the aforementioned challenges. In addition, the chirality and high hydrogen bonding capacity of carbohydrates makes them attractive for imparting asymmetry in chemical catalysis.8 In the case of PDT/PDI, carbohydrates may also impart specificity when designed to bind to lectins, particularly those involved in cancer and microbial infections.9

The number of methods developed for the synthesis of carbohydrate porphyrin conjugates (CPCs) have increased significantly in the past 20 years. Traditional methods for synthesizing meso-substituted CPCs involve either the condensation of a pyrrole with a glycosylated aldehyde,10 substitution of a glycosyl halide with the aryl phenol,11 or direct glycosylation.12 Condensation approaches to the synthesis of CPC’s generally require the synthesis of specialized aldehydes that are used in excess and often at temperatures that restrict the scope of the carbohydrates that can be used for this approach.10–11 On the other hand, the direct glycosylation method, which frequently involves the use of a specialized carbohydrate donor (e.g. a thioglycoside12a,b or glycosyl imidate12c), is often constrained by the stability of the donor, limited product selectivity due to mixtures of anomeric products, and low yields due to hydrolysis byproducts obtained during the glycosylation reaction.

The use of azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolarcycloadditon reactions for the synthesis of CPCs has opened new opportunities for glycoconjugation.13 This approach, which generally involves a reaction between a glycosyl azide/alkyne and a complementary porphyrin or porphyrin derivative, provides for a more modular approach. For example, in our earlier work we explored the feasibility of synthesizing CPCs using click chemistry. Reactions between Zn(II) 5,15-[p-(ethynyl)-diphenyl] or Zn(II) 5,10,15,20-[p-(ethynyl)-diphenyl] porphyrins and a series of readily available acetate protected glycosyl azides provided the corresponding glycoconjugates in high yields.14

In contrast to CPCs, however, examples of carbohydrate bacteriochlorin conjugates (CBcCs) remain scarce with only a handful of examples published to date. In an early example, Silva et al.15 prepared a series of furanose-based bacteriochlorins by reacting meso-tetrakis (pentafluorphenyl) porphyrin and a sugar nitrone which furnished the corresponding CBcC in 60% yield. More recently, Grin et al. published the synthesis of a series of mono- and di-glycoconjugates, from bacteriochlorophyll analogs in good yields.16

Despite the progress that has been made towards the preparation of CPCs and CBcCs, their syntheses often require specialized methods and protecting groups that restrict the generality of the approach. In addition, the carbohydrate moieties are often located far from the center of the macrocycle, which can limit their utility as asymmetric catalysts and PDT/PDI agents. In this work, we address these issues by developing rapid, modular, and high yielding approaches for the synthesis of CPCs and CBcCs where the carbohydrate is glycosylated directly to the macrocyclic ring. Surprisingly, we found that the unique properties of the two ring systems, porphyrins and bacteriochlorins, required different reactions for catalysis in order to furnish appreciable yields.

The asymmetrical nature and the proximity of the carbohydrate moiety to the macrocyclic center of the novel CPCs and CBcCs analogs prepared in this study are likely to have a significant impact on imparting stereoselectivity in chemical catalysis and activity in PDT/PDI. With respect to the latter, the carbohydrate may also impart biological selectivity by binding to lectins that are overexpressed on tumor cells or found on microbial membranes. Finally, the positioning of the carbohydrate near the macrocyclic center should ensure singlet oxygen delivery to the target cell upon lectin binding and activation.17

Results and Discussion

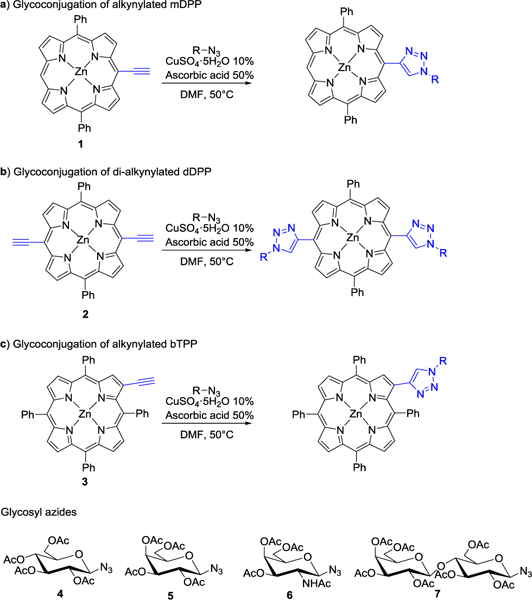

As an extension of our efforts to synthesize carbohydrate porphyrin CPC14 and phthalocyanines CPcC18 conjugates, we sought to use a similar copper(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolarcycloaddition protocol to create CPCs without the use of a “spacer” (Scheme 1). Our initial objective was to employ alkynylated porphyrin-based scaffolds, such as (5-ethynyl-10,20-diphenyldiporphinato)zinc(II) and [5,15-bis(ethynyl)-10,20-diphenylporphinato]zinc(II) (mDPP, 1, and dDPP, 2, respectively)19 and (2-ethynyl-5,10,15,20-tetraphenylporphinato)zinc(II) (bTPP, 3)19b, 20 in combination with acetate-protected glycosyl azides (4-7) as seen in Scheme 1. We opted to use zinc-based porphyrins because is well known that copper can readily insert into the porphyrin ring thereby inhibiting the copper catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition process. Zinc can serve as a temporary protecting group to protect the inner core and can be easily removed if desired.21

Scheme 1.

Glycoconjugation of porphyrin derivatives via azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition.

Using an acid promoted copper(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition protocol, glycoconjugation of mDPP (1) with 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-glycopyranosyl azide (4) resulted in a high yield of product (Table 1, entry 1) and no detectable side product formation. Reactions with 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-galactopyranosyl azide (5), 2-acetamido-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranosyl azide (6), and 2,2’,3,3’,4’,6,6’-hepta-O-acetyl-β-D-lactosyl azide. (7) gave similar results, as expected (Table 1, entry 2). Employing dDPP 2 and glycosyl azides (4-7) provided the corresponding multivalent glycoconjugates in high yield (Table 1, entries 4–8). It is worth noting that while the overall yields are slightly lower than those of the mDPP derivative, these yields reflect two “click reaction” processes, and the conversion per alkyne is within expectations. The use of bTPP 3 provided excellent yields using the same series of glycosyl azides, although we did observe a small reduction of isolated yield for the reaction with 6, which was due to challenges in purification rather than product conversion (Table 1, entries 9–12). It is important to note that if desired, the acetate protecting groups can be readily deprotected under Zempelén conditions as reported in the literature without influencing the macrocycle.22

Table 1.

Glycoconjugation of Alkynylated Porphyrins.

| Entry“[a] | Por (eq.) | R-N3(eq.) | Product | Yield(%)[b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 (1.1) | 5 (1.0) |  |

87[c] |

| 2 | 1 (1.1) | 5 (1.0) |  |

88[c] |

| 3 | 1 (1.1) | 6 (1.0) |  |

92 |

| 4 | 1 (1.1) | 7 (1.0) |  |

90[c] |

| 5[d] | 2(1.0) | 4 (1.1) |  |

82[c] |

| 6[d] | 2 (1.0) | 5 (1.1) |  |

79[c] |

| 7[d] | 2 (1.0) | 6 (1.0) |  |

89 |

| 8[d] | 2 (1.0) | 7 (1.0) | 74[c] | |

| 9 | 3 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) |  |

98[c] |

| 10 | 3 (1.1) | 5 (1.0) |  |

98[c] |

| 11 | 3 (1.1) | 6 (1.0) |  |

84 |

| 12 | 3 (1.1) | 7 (1.0) |  |

99[c] |

Reactions were carried out at 50oC for 48 h under N2 in DMF with 10 mol % of CuSO4·5H2O and 50 mol % of ascorbic acid

Isolated yields,

Average of two trials

reaction carried out over 72 h

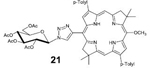

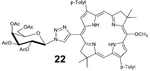

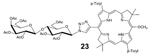

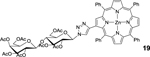

We sought to extend this methodology to develop a general procedure to create carbohydrate bacteriochlorin conjugates (CBcCs) in a similar fashion. Our efforts led us to use a previously reported alkynylated bacteriochlorin MeO-BC 2023 (Scheme 2) that is analogous to mDPP 1 for the direct conjugation of carbohydrates as seen in Scheme 1. In this case, an unmetallated bacteriochlorin was employed without concern for the inhibition of the glycoconjugation process due to the limited capacity of bacteriochlorins to readily chelate metals under these conditions.24 Under the same acid promoted copper(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition protocol employed in Table 1 (Method A), we were disappointed to observe the desired CBcCs in low yields (Table 2, entries 1 and 3). Closer inspection of the crude reaction mixtures provided evidence via 1H NMR that the alkyne residue was hydrated and converted into ketone 24 under these conditions (Scheme 2). Interestingly, ketone formation was not observed in the alkynylated porphyrin scaffolds which underwent the same 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction (Table 1). Altering the copper(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolarcycloaddition conditions to a base promoted protocol provided high yields for each of the glycoconjugates attempted (Table 2, entries 2, 4 and 5) and eliminated, as observed on 1H NMR, the formation of the ketone side product.

Scheme 2.

Glycloconjugation of 20 under acidic conditions.

Table 2.

Glycoconjugation of 20

Reactions were carried out at 50°C for 48 h under N2 in DMF.

Conditions A: 10 mol % of CuSO4·5H2O and 50 mol % of ascorbic acid., B: 15 mol % Cul and 50 mol % DIPEA.

Isolated yields

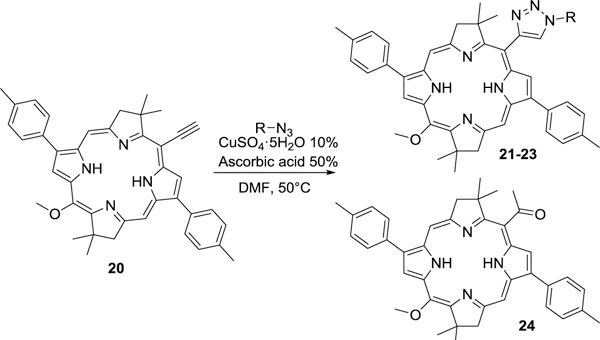

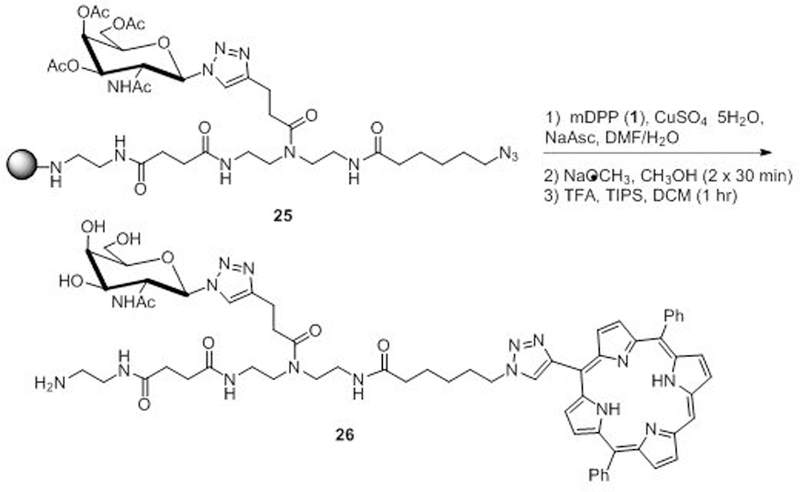

To evaluate the potential use of this methodology for the conjugation of more complex carbohydrate structures, the synthesis of a porphyrin-based glycoconjugate was performed completely on solid support. Today complex oligosaccharides as well as glycomimetics are often synthesized on solid support.25 In addition, several examples exist in the literature where porphyrins have been synthesized using solid-supported strategies.26 We first constructed a glycoconjugate consisting of a TDS27 building block, 2-acetamido-3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranosyl azide, and an 6-azidohexanoic acid linker (Scheme 3, 25). Base promoted azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolarcycloadditon reaction of the scaffold with 1 was accomplished under mild conditions at room temperature to give the desired conjugate, which was then deprotected under basic conditions, cleaved from the resin using TFA (which simultaneously deprotects the zinc core), and purified via reverse-phase HPLC to give 26 as a purple solid in greater than 91% purity (See SI for details). This result demonstrates the extension of this methodology to the solid supported synthesis of glycoconjugate mimetics bearing porphyrins for use as photosensitizers or catalysts.

Scheme 3.

Porphyrin conjugation on solid support.

Conclusions

In this work, we have established general protocols for the synthesis of glycosylated carbohydrate porphyrin and bacteriochlorin conjugates utilizing CuAAC. The reported approaches are adjusted based on the unique properties of each ring system. In total, fifteen unique compounds are reported for the first time in high to excellent yield, including directly glycosylated meso-substituted porphyrins and bacteriochlorins, and beta-substituted porphyrins. We were also able to demonstrate the generality of this approach through application to the first solid-supported synthesis of an oligo(amidoamine)-based porphyrin glycoconjugate. Continuing efforts are focused on exploring the application of these systems for use as stereoselective catalysts and PDT/PDI agents.

Experimental Section

General Considerations.

All starting materials were synthesized following published literature procedures19–20,23 from commercially available reagents and solvents. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were obtained using a Bruker Advance III 400 with Sample Xpress Lite auto sampler. UV-Vis spectra were obtained in DMSO using an Agilent Technologies Cary 8454 UV-Vis spectrometer. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained on an Agilent Technologies 6520B Accurate-Mass Q-TOF MS with a Dual ESI ion source interfaced to an Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity II LC. MALDI measurements were made with a MassTech AP-MALDI(ng) HR ion source attached to the Agilent 6520B Q-TOF MS using a CHCA matrix.

Method for the general synthesis of mDPP (1) glycoconjugates: mDPP (1, 55.0 mmol), azido-carbohydrate (4,5,6,or 7, 50.0 mmol), CuSO4·5H2O (10 mol %) and ascorbic acid (50 mol %) were added to a dry Schlenk tube and evacuated with stirring for 45 minutes. DMF (5 mL) was added under nitrogen atmosphere and the Schlenk tube was capped. The mixture was placed in an oil bath at 50 °C with stirring for 48 hours. The reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by automated chromatography (Teledyne ISCO Combiflash Rf plus) using a Redisep Rf 12 gram, 16.8 mL column with a flow rate of 30 mL/min (hexanes: acetone 100:0 to 0:100 over 17 minutes). Alternate purification: The reaction mixture was initially purified by flash chromatography (silica gel, EtOAc: hexane (v/v) 1:1) to remove impurities. The solvent system was increased to 100% EtOAc to yield title compound.

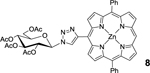

8: mDPP-Glc (Table 1, Entry 1) was obtained as a purple solid (41.5 mg, 90.2% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.41, (hexanes: acetone 55:45 [v:v]) 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.39 (s, 1H), 9.51 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H), 9.37 (s, 1H), 9.01 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 8.93 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H), 8.88 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 8.24 (m, 4H), 7.85 (m, 6H), 6.78 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 6.07 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 5.81 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H), 5.37 (t, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 4.63–4.61 (m, 1H), 4.28–4.27 (m, 2H), 2.13 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.12, 169.63, 169.47, 169.16, 149.55, 149.42, 149.31, 149.18, 148.61, 142.54, 134.37, 134.34, 132.43, 131.80, 131.17, 127.53, 126.90, 126.70, 119.90, 107.07, 106.88, 84.67, 73.52, 72.06, 71.11, 67.73, 61.83, 20.57, 20.45, 20.34, 20.21. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε) 422 (5.71), 553 (4.29), 592 (3.59). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: [M]+ Calcd. for C48H39N7O9Zn 921.2101; Found 921.2105.

9: mDPP-Gal (Table 1, Entry 2) was obtained as a purple solid (41.3mg, 88.4% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.47, (hexanes: acetone 55:45 [v:v]). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.40 (s, 1H), 9.52 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H), 9.29 (s, 1H), 8.96 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 8.92 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H), 8.88 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 8.22–8.23 (m, 4H), 7.84–7.85 (m, 6H), 6.69 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 5.95 (t, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 5.71 (dd, J = 10.1, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 5.56 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 4.86–4.83 (m, 1H), 4.31–4.19 (m, 2H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.15 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.12, 170.04, 169.60, 169.20, 149.55, 149.50, 149.35, 149.16, 148.53, 142.55, 134.35, 132.43, 131.81, 131.14, 127.53, 127.03, 126.71, 119.90, 107.01, 85.09, 73.22, 70.40, 68.75, 67.35, 61.69, 20.59, 20.42, 20.33. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 422 (5.58), 553 (4.17), 592 (3.50). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: [M]+ Calcd for C48H39N7O9Zn 921.2101; Found 921.2105.

10: mDPP-GalNAc (Table 1, Entry 3) was obtained as a purple solid (46.7 mg, 92% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.27 (ethyl acetate: hexanes 7:3 [v:v]). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.39 (s, 1H), 9.51 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 2H), 9.08 (m, 2H), 9.07 (s, 1 H), 8.93 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 2H), 8.88 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 8.48 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (m, 4H), 7.85 (s, 6H), 6.44 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 5.55 (m, 1H), 5.50–5.46 (m, 1H), 5.05–5.00 (m, 1H), 4.78–4.75 (m, 1H), 4.32–4.28 (m, 1H), 4.23–4.18 (m, 1H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 1.95 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.66, 170.54, 170.44, 170.16, 150.09, 150.00, 149.83, 149.62, 148.57, 143.08, 134.85, 132.87, 132.23, 131.95, 128.00, 127.19, 127.14, 120.33, 107.81, 107.27, 88.68, 87.05, 73.64, 70.93, 67.20, 62.27, 49.60, 23.20, 21.12, 21.07, 21.01, 20.99, 20.91. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 422 (5.61), 553 (4.20), 592 (3.55). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd for C48H40N8O8Zn [M]+ 920.2261; Found [M]+ 920.2272.

11: mDPP-Lac (Table 1, Entry 4) was obtained as a purple solid (56.4 mg, 90.2% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.31 (hexanes: acetone 55:45 [v:v]). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.38 (s, 1H), 9.51 (s, 1H), 9.50 (s, 1H), 9.33 (s, 1H), 9.02 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 8.94 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H), 8.90 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 8.25 (m, 4H), 7.86 (m, 6H), 6.76 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 5.98 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 5.75 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 5.32–5.27 (m, 2H), 5.02–4.96 (m, 2H), 4.63–4.61 (m, 1H), 4.55–4.51 (m, 1H), 4.37–4.34 (m, 1H), 4.22–4.17 (m, 2H), 4.12 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.18 (s, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 2.13 (s, 3H), 2.12 (s, 3H), 2.10 (s, 3H), 2.05 (s, 3H), 1.96 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): 170.37, 169.97, 169.95, 169.58, 169.45, 169.26, 169.16, 149.58, 149.45, 149.34, 149.20, 148.56, 142.56, 134.36, 132.44, 131.81, 127.54, 126.88, 126.72, 119.93, 107.11, 106.88, 100.20, 84.52, 76.01, 74.70, 72.15, 71.42, 70.37, 69.81, 68.98, 67.17, 62.32, 60.98, 20.69, 20.53, 20.48, 20.43, 20.36, 20.27. UV-Vis, (DMSO), λmax (nm), (Log ε) 422 (5.69), 553 (4.26), 592 (3.61). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd for C60H55N7O17Zn [M]+ 1209.2946; Found [M]+ 1209.2950.

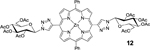

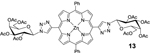

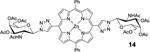

Method for the general synthesis of dDPP (2) glycoconjugates: mDPP (2) (50.0 mmol), azido-carbohydrate (4,5,6,or 7) (110.0 mmol), CuSO4·5H2O (10 mol %) and ascorbic acid (50 mol %) were added to a dry Schlenk tube and evacuated with stirring for 45 minutes. DMF (5 mL) was added under nitrogen atmosphere and the Schlenk tube was capped. The mixture was placed in an oil bath at 50 °C with stirring for 72 hours. The reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by automated chromatography (Teledyne ISCO Combiflash Rf plus) using a Redisep Rf 12 gram, 16.8 mL column with a flow rate of 30 mL/min (hexanes: acetone 100:0 to 0:100 over 17 minutes). Alternate purification: The reaction mixture was initially purified by flash chromatography (silica gel, EtOAc: hexane (v/v) 1:1) to remove impurities. The solvent system was increased to 100% EtOAc to yield title compound.

12: dDPP-Glc (Table 1, Entry 5) was obtained as a purple solid (53.8mg, 79.2% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.24 (hexanes: ethyl acetate 1:1 [v:v]). 1H NMR (400MHz, DMSO): δ 9.39 (s, 2H), 9.01 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.85 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.23–8.21 (m, 4H), 7.85–7.84 (m, 6H), 6.78 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.07 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 5.81 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 2H), 5.36 (t, J = 9.8 Hz, 2H), 4.63–4.60 (m, 2H), 4.27 (m, 4H), 2.12 (s, 6H), 2.09 (s, 6H), 2.07 (s, 6H), 2.04 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.12, 169.63, 169.48, 169.19, 149.65, 148.38, 142.50, 134.28, 131.95, 131.49, 127.63, 127.02, 126.71, 120.78, 107.87, 84.68, 73.53, 72.04, 71.12, 67.22, 61.83, 20.58, 20.45, 20.34, 20.21. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 428 (5.70), 560 (4.24), 603 (3.89). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: [M]+ Calcd for C64H58N10O18Zn 1318.3222; Found 1318.3202.

13: dDPP-Gal (Table 1, Entry 6) was obtained as a purple solid (53.9 mg 79.5% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.40 (hexanes: ethyl acetate 3:7 [v:v]). 1H NMR: (400MHz, DMSO): δ 9.31 (s, 2H), 8.97 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.85 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.22–8.20 (m, 4H), 7.85–7.83 (m, 6H), 6.69 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 5.95 (t, J = 9.8 Hz, 2H), 5.73–5.69 (m, 2H), 5.57 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 2H), 4.86–4.83 (m, 2H), 4.31–4.19 (m, 4H), 2.20 (s, 6H), 2.15 (s, 6H), 2.08 (s, 6H), 2.04 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.12, 170.05, 169.60, 169.23, 149.71, 149.65, 148.29, 142.51, 134.25, 131.96, 131.45, 127.63, 127.12, 126.71, 120.78, 107.81, 85.11, 73.23, 70.38, 68.75, 67.35, 61.68, 20.58, 20.42, 20.32. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 427 (5.75), 559 (4.29), 602 (3.88). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: [M]+ Calcd for C64H58N10O18Zn 1318.3222; Found 1318.3218.

14: dDPP-GalNAc (Table 1, Entry 7) was obtained as a purple solid (55 mg 89% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.10 (hexanes: ethyl acetate 3:7 [v:v]). 1H NMR: (400MHz, DMSO): δ 9.07 (s, 2H), 9.05 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.82 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.45 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 8.22–8.20 (m, 4H) 7.84–7.83 (m, 6H), 6.41 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 2H), 5.3 (m, 2H), 5.46–5.43 (m, 2H), 5.01–4.94 (m, 2H), 4.75–4.72 (m, 2H), 4.30–4.15 (m, 4H), 2.17 (s, 6H), 2.09 (s, 6H), 2.02 (s, 6H), 1.93 (s, 6H). 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.64, 170.53, 170.44, 170.14, 150.24, 150.08, 148.33, 143.07, 134.72, 132.30, 132.20, 128.08, 127.17, 121.12, 108.51, 87.05, 73.63, 70.89, 67.14, 62.24, 49.60, 23.18, 21.09, 20.98, 20.93. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 427 (5.72), 559 (4.23), 602 (3.86). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: [M]+ Calcd for C64H60N12O16Zn 1316.3542; Found 1316.3507.

15: dDPP-Lac (Table 1, Entry 8) was obtained as a purple solid (75.5 mg, 77.7% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.64 (hexanes: ethyl acetate 4:1 [v:v]). 1H NMR (400MHz, DMSO): δ 9.29 (s, 2H), 8.97 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.82 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.20–8.19 (m, 4H), 7.84–7.82 (m, 6H), 6.70 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 5.91 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 2H), 5.69 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 5.27–5.22 (m, 4H), 4.96–4.90 (m, 4H), 4.57–4.52 (m, 2H), 4.49–4.45 (m, 2H), 4.32–4.29 (m, 2H), 4.16–4.12 (m, 4H), 4.08–4.06 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 4H), 2.14 (s, 6H), 2.10 (s, 12H), 2.08 (s, 6H), 2.06 (s, 6H), 2.02 (s, 6H), 1.92 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.35, 169.93, 169.56, 169.41, 169.25, 169.13, 149.63, 148.27, 142.49, 134.26, 131.92, 131.47, 127.63, 126.96, 126.71, 120.77, 107.87, 100.17, 84.48, 75.97, 74.65, 72.08, 71.38, 70.32, 69.77, 68.94, 67.13, 60.95, 20.68, 20.52, 20.45, 20.40, 20.33, 20.24. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 427 (5.70), 560 (4.22), 603 (3.84). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd for C88H90N10O34Zn [M]+ 1894.4912; Found [M]+ 1894.4889.

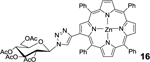

Method for the general synthesis of bTPP (3) glycoconjugates: bTPP (3, 55.0 mmol), azido-carbohydrate (4,5,6,or 7) (50.0 mmol), CuSO4·5H2O (10 mol %) and ascorbic acid (50 mol %) were added to a dry Schlenk tube and evacuated with stirring for 45 minutes. DMF (5 mL) was added under nitrogen atmosphere and the Schlenk tube was capped. The mixture was placed in an oil bath at 50 °C with stirring for 48 hours. The reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by automated chromatography (Teledyne ISCO Combiflash Rf plus) using a Redisep Rf 12 gram, 16.8 mL column with a flow rate of 30 mL/min (hexanes: acetone 100:0 to 0:100 over 22 minutes). Alternate purification: The reaction mixture was initially purified by flash chromatography (silica gel, EtOAc: hexane (v/v) 1:1) to remove impurities. The solvent system was increased to 100% EtOAc to yield title compound.

16: bTPP-Glc (Table 1, Entry 9) was obtained as a purple solid (53.9mg, 98% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.41 (hexanes: acetone 6:4 [v:v]). 1H NMR (400MHz, DMSO): δ 8.80–8.77 (m, 5H), 8.72 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 8.21–8.18 (m, 6H), 8.04–8.02 (m, 1H), 7.79 (m, 10H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.50–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.32–7.29 (m, 1H), 6.23–6.21 (m, 1H), 5.61–5.58 (m, 2H), 5.23–5.18 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.42 (m, 1H), 4.37–4.33 (m, 1H), 4.26–4.23 (m, 1H), 2.17 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.90, (s, 3H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.16, 169.60, 169.36, 168.53, 162.27, 150.20, 149.72, 149.62, 149.59, 149.55, 149.22, 146.56, 145.47, 144.29, 142.72, 142.59, 142.56, 141.35, 135.78, 134.76, 134.56, 134.41, 134.14, 132.43, 131.78, 131.16, 127.57, 127.50, 126.61, 126.54, 126.03, 125.82, 122.48, 121.27, 120.62, 120.28, 120.17, 83.62, 73.12, 72.43, 69.96, 67.61, 61.95, 20.60, 20.41, 20.27, 20.14. UV-Vis: DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 431 (5.51), 564 (5.36), 604 (5.01). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: [M]+ Calcd for C60H47N7O9Zn 1073.2727; Found 1073.2736.

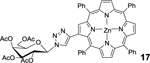

17: bTPP-Gal (Table 1, Entry 10) was obtained as a purple solid (53.9mg, 98.0% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.39 (hexanes: acetone 6:4 [v:v]). 1H NMR (400MHz, DMSO): δ 8.84 (s, 1H), 8.79–8.76 (m, 4H), 8.71 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 8.64 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (m, 6H), 8.03–8.01 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.86–7.79 (m, 10H), 7.57–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.39 (s, 1H), 7.36–7.35 (m, 1H), 6.11 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 5.62 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 5.51–5.48 (m, 2H), 4.66–4.63 (m, 1H), 4.28–4.26 (m, 2H), 2.29 (s, 3H), 2.12 (s, 3H), 1.97 (s, 3H), 1.91 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.12, 169.56, 168.70, 150.24, 149.77, 149.66, 149.64, 149.58, 149.28, 146.63, 145.40, 144.18, 142.77, 142.61, 142.58, 141.57, 134.18, 132.48, 131.84, 131.18, 127.57, 126.68, 122.44, 121.20, 120.71, 120.35, 120.20, 84.12, 72.75, 70.70, 67.47, 67.41, 61.74, 20.62, 20.51, 20.36, 20.26. UV-Vis: DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 431 (5.66), 564 (4.27), 604 (3.90). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: [M]+ Calcd for C60H47N7O9Zn 1073.2727; Found 1073.2721.

18: bTPP-GalNac (Table 1, Entry 11) was obtained as a purple solid (50.0 mg, 84% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.31 (hexanes: ethyl acetate 3:7 [v:v]). 1H NMR: (400MHz, DMSO): δ 8.86 (s, 1H), 8.79–8.76 (m, 4H), 8.71 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.24–8.14 (m, 6H), 8.11–8.06 (m, 2H), 7.82–7.76 (m, 10), 7.64–7.52 (m, 2H), 7.32–7.28 (m, 2H), 5.92 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 5.47–5.46 (m, 1H), 5.32–5.29 (m, 1H), 4.58–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.31–4.30 (m, 2H), 2.34 (s, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 1.95 (s, 3H), 1.61 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.63, 170.60, 170.16, 170.04, 150.71, 150.22, 150.09, 150.07, 150.00, 149.97, 141.14, 145.78, 144.11, 143.27, 1473.09, 143.06, 141.99, 136.27, 135.34, 135.09, 134.94, 134.64, 134.53, 132.98, 132.35, 132.30, 132.24, 131.61, 128.68, 128.02, 127.13, 127.06, 126.71, 126.38, 122.18, 121.70, 121.18, 120.79, 120.60, 85.10, 73.10, 70.83, 67.30, 62.26, 48.37, 23.00, 21.15, 21.08, 20.90. UV-Vis: DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 431 (5.31), 564 (3.95), 604 (3.61). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: [M]+ Calcd for C60H48N8O8Zn 1072.2887; Found 1072.2901.

19: bTPP-Lac (Table 1, Entry 12) was obtained as a purple solid (67.3mg, 99.3% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.47 (hexanes: acetone 1:1 [v:v]). 1H NMR: (400MHz, DMSO): δ 8.81–8.75 (m, 5H), 8.72 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 8.21–8.16 (m, 6H), 8.03–7.98 (m, 1H), 7.81–7.79 (m, 10H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.49–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.30 (m, 1H), 6.15–6.12 (m, 1H), 5.51–5.48 (m, 2H), 5.30–5.23 (m, 2H), 4.96–4.89 (m, 2H), 4.54–4.51 (m, 1H), 4.32–4.29 (m, 2H), 4.24–4.20 (m, 1H), 4.09–4.04 (m, 3H), 2.22 (s, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 1.94 (s, 3H), 1.90 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 170.37, 169.87, 169.49, 169.41, 169.09, 168.60, 150.15, 149.69, 149.59, 149.57, 149.53, 149.20, 146.54, 145.44, 144.15, 142.69, 142.57, 142.54, 141.36, 135.75, 134.39, 134.12, 131.76, 127.55, 127.49, 126.60, 126.52, 122.54, 121.21, 120.60, 120.27, 120.14, 99.99, 83.39, 75.78, 74.23, 72.65, 70.33, 70.14, 69.75, 68.93, 67.10, 62.46, 60.89, 20.66, 20.45, 20.39, 20.35, 20.29, 20.17. UV-Vis: DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε): 431 (5.65), 564 (4.25), 604 (3.89). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd for C72H63N7O17Zn [M]+ 1361.3572; Found [M]+ 1361.3566.

Method for the general synthesis of Bacteriochlorin (20) glycoconjugates: 20 (27.5 mmol), azido-carbohydrate (4,5,or 6) (25.0 mmol), Cu(I) (15 mol %) were added to a dry Schlenk tube and evacuated with stirring for 45 minutes. DIPEA (50 mol %) was added followed by DMF (0.01M) under nitrogen atmosphere and the Schlenk tube was capped. The mixture was placed in an oil bath at 50 °C with stirring for 48 hours. The reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by automated chromatography (Teledyne ISCO Combiflash Rf plus) using a Redisep Rf 12-gram, 16.8 mL column with a flow rate of 30 mL/min (hexanes: acetone 100:0 to 0:100 over 22 minutes).

21: Bac-Glc (Table 2, Entry 1 and 4) was obtained as a dark pink solid (22.9 mg, 85.8% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.44 (hexanes: acetone 65:35[v:v]). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.96 (bs, 1H), 8.87–8.84 (m, 2H), 8.37 (bs, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.14 (d, J = 7.48 Hz, 2H), 8.07 (d, J = 7.56 Hz, 2H), 7.59 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 7.68 Hz, 2H), 6.19 (d, J = 9.24 Hz, 1H), 5.71 (t, J = 9.48 Hz, 1H), 5.60 (t, J = 9.44 Hz, 1H), 5.36 (t, J = 9.76 Hz, 3H), 4.51 (s, 3H), 4.46–4.40 (m, 2H), 4.29–4.26 (m, 1H), 4.18–4.16 (m, 1H), 2.61 (s, 3H), 2.59 (s, 3H), 2.12 (s, 3H), 2.11–2.10 (m, 9H), 1.95 (s, 3H), 1.92 (s, 3H), 1.90 (s, 3H), 1.82 (s, 3H), −1.53 (s, 1H), −1.81 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.71, 170.11, 169.55, 169.25, 149.39, 137.37, 137.29, 137.16, 134.83, 133.69, 131.22, 129.91, 129.80, 123.27, 120.34, 116.58, 94.17, 95.96, 86.59, 75.60, 72.73, 70.91, 68.11, 65.25, 61.70, 51.55, 47.53, 46.18, 45.51, 31.35, 31.04, 29.83, 21.53, 20.87, 20.73, 20.71, 20.56. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε) 361 (5.02), 379 (5.12), 519 (4.54), 741 (5.02). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd for C55H59N7O10 [M]+ 977.4323; Found [M]+ 977.4298.

22: Bac-Gal (Table 2, Entry 2 and 5) was obtained as a dark pink solid (21.9 mg, 88.1% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.43 (solvent system hexanes: acetone 65:35 [v:v]). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.98 (s, 1H), 8.88 (s, 1H), 8.86 (s, 1H), 8.41 (s, 1H), 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 7.44 Hz,2H), 8.10 (d, J = 7.52 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.52 Hz,2H), 7.56 (d, J = 7.56 Hz, 2H), 6.19 (d, J = 9.16 Hz, 1H), 5.85 (t, J = 9.68 Hz, 1H), 5.68 (m, 1H), 5.46–5.42 (m, 1H), 4.53 (s, 3H), 4.44–4.40 (m, 3H), 4.33–4.27 (m, 3H), 4.09–4.03 (m, 1H), 2.62 (s, 3H), 2.60 (s, 3H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.18 (s, 3H), 2.13 (s, 3H), 2.10 (s, 3H), 1.96 (s, 3H), 1.94 (s, 3H), 1.91 (s, 3H), 1.86 (s, 3H), −1.56 (s, 1H), −1.84 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.50, 170.16, 169.99, 169.48, 160.52,153.71, 149.34, 137.38, 137.22, 137.15, 136.50, 135.64, 134.83, 134.25, 134.11, 133.75, 133.49, 131.33, 131.32, 130.37, 129.91, 129.81, 123.37, 120.41, 116.59, 99.96, 97.10, 95.96, 87.09, 74.48, 70.98, 68.53, 67.11, 65.24, 61.35, 51.54, 47.54, 46.20, 45.50, 31.45, 31.33, 31.05, 30.99, 29.82, 21.51, 20.82, 20.78, 20.68. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε) 360 (5.05), 379 (5.12), 519 (4.54), 741 (5.03). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd for C55H59N7O10 [M]+ 977.4323; Found [M]+ 977.4300.

23: Bac-Lac (Table 2, Entry 3 and 6) was obtained as a dark pink solid (26.1 mg, 83.7% yield). TLC analysis Rf = 0.29 (solvent system hexanes: acetone 65:35 [v:v]). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.97 (bs, 1H), 8.89–8.83 (m, 2H), 8.38 (bs, 1H), 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.145 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 8.07 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.59 (d, J = 7.76 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.18 (d, J = 8.76 Hz, 1H), 5.68–5.60 (m, 2H), 5.41 (d, J = 2.88 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (dd, J = 10.36, 7.88 Hz, 1H), 5.02 (dd, J = 10.44, 3.40 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (d, J = 11.64 Hz, 1H), 4.60 (d, J = 7.88 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (s, 3H), 4.30–4.26 (m, 1H), 4.21–4.15 (m, 3H), 4.13–4.09 (m, 2H), 3.96–3.92 (m, 1H), 2.62 (s, 3H), 2.59 (s, 3H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 2.15 (s, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 2.13 (s, 3H), 2.11 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 1.94 (s, 3H), 1.93 (s, 3H), 1.89 (s, 3H), 1.83 (s, 3H), −1.52, (s, 1H), −1.81 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.46, 170.38, 170.24, 170.18, 169.61, 169.47, 169.21, 149.24, 137.38, 137.20, 131.19, 129.90, 129.79, 123.24, 101.28, 86.37, 76.41, 75.86, 72.53, 71.21, 71.09, 71.04, 69.24, 66.75, 61.95, 60.98, 51.54, 47.52, 46.19, 45.51, 31.01, 29.80, 21.50, 20.96, 20.90, 20.77, 20.63, 20.57. UV-Vis, DMSO, λmax (nm), (Log ε) 361 (5.02), 379 (5.13), 520 (4.54), 741 (5.03). HRMS (MALDI) m/z: Calcd for C67H75N7O18 [M]+ 1265.5168; Found [M]+ 1265.5132.

Method for oligo(amidoamine)-based porphyrin glycoconjugate (26) synthesis:

Resin preparation.

A commercially available trityl-Tentagel-Cl resin was modified with an ethylendiamine (EDA) linker. The loading from the modified resin was determined by an Fmoc based loading test as previously described.27 This method measures the production of fulvene by UV-Vis after treatment with a solution of 25% piperidine in DMF by monitoring. The loading was 0.20 mmol/g. The resins were swollen in 5 mL of DCM for 30 min and subsequently washed 10 times with 10 mL of DMF.

General Coupling Protocol.

Building blocks were coupled to the resin using a mixture of building block (0.5 mmol. 5 eq) and PyBOP (0.5 mmol, 5eq) dissolved in DMF (2 mL) to which DIPEA (2 mmol, 20 eq) was added. The mixture was shaken for 30 s under a nitrogen stream for activation and subsequently added to the resin. The resin with the coupling mixture was shaken for 1 h. After that, the resin was washed from excessive reagent with DMF (10 × 5 mL).

Fmoc Cleavage.

The Fmoc protecting group was cleaved by adding of a solution of 25% piperidine in DMF (5 mL). The deprotection was performed twice, the first time for 20 min and the second time for 10 min. After that, the resin was washed thoroughly 10 times with DMF.

General CuAAC Protocol for GlcNAcN3.

Acetyl protected glycosyl azide (0.25 mmol, 2.5 eq per alkyne group) was dissolved in DMF (2 mL). To the mixture was added sodium ascorbate (30 mol% per alkyne group) dissolved in 0.5 mL of water, followed by CuSO4 (30 mol% per alkyne group) dissolved in 0.5 mL water. The reaction mixture was flushed with nitrogen and then shaken overnight. Upon completion of the reaction, the resin was washed extensively with a 23 mM solution of sodium diethyldithiocarbamate in DMF (5 mL), followed by water (5 mL), DMF (5 mL) and then DCM (5 mL). This washing cycle was repeated until the resin was no longer colored.

CuAAC protocol mDPP Conjugation.

Porphyrin 1 (0.15 mmol, 1.5 eq) was dissolved in DMF (2 mL). To the mixture was added sodium ascorbate (30 mol% per alkyne group) dissolved in 0.5 mL of water, followed by CuSO4 (30 mol% per alkyne group) dissolved in 0.5 mL water. The reaction mixture was flushed with nitrogen and then shaken overnight. This process was repeated twice to ensure complete conjugation. Upon completion of the reaction, the resin was washed extensively with a 23 mM solution of sodium diethyldithiocarbamate in DMF (5 mL), followed by water (5 mL), DMF (5 mL) and then DCM (5 mL). This washing cycle was repeated until the resin was no longer colored.

On Resin Acetyl Deprotection.

In order to remove the acetyl protective groups of the now glycosylated carbohydrate, a solution of 0.2 M sodium methanolate in methanol (5 mL) was added to the resin and shaken for 30 min. Subsequently the resin was washed DMF (10 × 5 mL), MeOH (10 × 5 mL) and DCM (10 × 5 mL).

Cleavage from solid phase.

A mixture of 60% TFA, 35% DCM and 5% of TIPS (5 mL) was added to the resin and shaken for 1 h. The filtrate was poured into 35 mL cold diethyl ether. The resin was washed with an additional 5 mL of DCM which was also added to the cold ether. The resulting precipitate was centrifuged and the ether decanted. The crude product was dried over a stream of nitrogen, dissolved in 3 mL of water and lyophilized.

TFA Salt Removal with Anion Exchange Resin.

TFA removal was performed with 2 g AG1-X8, quaternary ammonium resin. The resin was loaded into a syringe containing a frit, and washed 1.6 M acetic acid in water (3 × 15 mL) and 0.16 M acetic acid in water (3 × 15 mL). The oligomer was dissolved in 2 mL of water and added to the syringe containing the resin. The mixture was and shaken for 1h then washed with water (3 × 2 mL). All water fraction was collected and lyophilized before being purified by preparative RP-HPLC.

Reversed Phase - High Pressure Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry.

Measurements were performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity instrument coupled to a variable wavelength detector (VWD) (set to 214 nm) and a 6120 Quadrupole LC/MS containing an Electrospray Ionization (ESI) source (operated in positive ionization mode in a m/z range of 200 to 2000). As HPLC column a Poroshell 120 EC-C18 (3.0×50 mm, 2.5 μm) RP column from Agilent was used. The mobile phases A and B were H2O/ACN (95/5) and H2O/ACN (5/95), respectively. Both mobile phases contained 0.1% of formic acid. Samples were analyzed at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min using a linear gradient starting with 100% mobile phase A reaching 50% mobile phase B within 30 min. The temperature of the column compartment was set to 25 °C. UV and MS spectral analysis was done within the OpenLab ChemStation software for LC/MS from Agilent Technologies.

26 was obtained as a dark pink solid. RP-HPLC (5%/95% A→ 50/50% A in 30 min): tR = 18.90min, Purity = 91%; 18% yield (21.5 mg). 1H NMR (300 MHz, D2O) 10.17 (s, 1H), 9.26, 9.25 (s, s, 2H), 9.00–8.73 (m, 6H), 8.53 (s, 1H), 8.09, 8.07 (s, s, 4H), 7.83–7.61 (m, 7H), 5.50, 5.48, 5.46, 5.45 (dd, J = 9.8Hz, 5.1Hz, 1H), 4.71–4.61 (m, 2H), 4.44–4.29 (m, 1H), 3.86, 3.85, 3.83, 3.82 (dd, J = 8.9Hz, 2.7Hz, 1H), 3.72– 3.55 (m, 1H), 3.15– 3.01 (m, 2H), 2.96–2.81(m, 4H), 2.80–2.65 (m, 2H), 2.60–2.50, 2.39–2.25 (m, 2H), 2.25–1.99 (m, 8H), 1.75–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.61, 1.60 (s, s, 3H), 1.53–1.37 (m, 2H), 1.33–0.71 (m, 2H). HRMS Calcd for C63H72N16O9 [M + 2H]2+ 599.29; Found [M + 2H]2+ 599.29.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

JVR and NLS would like to thank the NIH for supporting this work through an AREA award (1R15GM119067–01). JVR would like to thank USC Upstate and the Office of Sponsored Awards and Research Support for partial funding of this work. NLS would like to thank the National Science Foundation for an MRI award to Davidson College (#1624377). MCB, DGD, MEL, JEC, and CFD would like to thank the University of South Carolina and the Office of Undergraduate Research for a Magellan Scholarship. NLF would like to thank the Beckman Foundation for support. KN and LH would like to thank the HHU Stay Connected program and Boehringer Ingelheim Foundation (Plus 3 program) for support.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document

References

- [1].Catalysis and Bio-Inspired Systems, Part I in Handbook of Porphyrin Science (Eds: Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R) World Scientific, 2000. vol. 10, ch. 43–48, pp. 1–370. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jones RD, Summerville DA, Basolo F, Chem. Rev. 1979, 79, 139–179. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hagfeldt A, Boschloo G, Sun L, Kloo L, Pettersson H, Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6595–6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].For a recent review see: Ethirajan M, Chen Y, Joshi P, Pandey RK, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 340–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chen Q, Huang Z, Luck D, Beckers J, Brun P-H, Wilson BC, Scherz A, Salomon Y, Hetzel FW, Photochem. Photobiol. 2002, 76, 438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Liu TWB, Chen J, Burgess L, Cao W, Shi J, Wilson BC, Zheng G, Theranostics G 2011, 1, 354–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yu Z, Ptaszek M, J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10678–10691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Weissleder T, Pittet MJ, Nature 2008, 452, 580–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Maillard P, Guerquin-Kern JL, Momenteau M, Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 4901–4904. [Google Scholar]; b) Vilain S, Maillard P, Momenteau M, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1994, 1697–1698. [Google Scholar]; c) Vilain-Deshayes S, Robert A, Maillard P, Meunier B, Momenteau M, J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1996, 113, 23–24. [Google Scholar]; d) Ho C-M, Zhang J-L, Zhou C-Y, Chan O-Y, Yan JJ, Huang J-S, Che C-M, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1886–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Singh S, Aggarwal A, Bhupathiraju NVSDK, Arianna G, Tiwari K, Drain CM, Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 10261–10306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Moylan C, Scanlan EM, Senge MO, Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22(19), 2238–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Titov DV, Gening ML, Tsvetkov YE, Nifantiev NE, Russ. Chem. Rev. 2014, 93(6), 523–554. [Google Scholar]; d) Zheng X, Pandey RK, Anti-Cancer Agents in Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 241–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Chang D-D, Yang W-H, H Sai X, Wang J-X, Chen L, Pan J-M, Yan Y-S, Dai Y-R, J. Polym. Res. 2018, 25:257, 1–12. [Google Scholar]; f) Pereira PMR, Rizvi W, Bhupathiraju NVSDK, Berisha N, Fernandes R, Tomé JPC, Drain C.M CM. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 306–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Halazy S, Berges V, Ehrhard A and Danzin C, Bioorg. Chem. 1990, 18, 330–344. [Google Scholar]; b) Van der Made AW, Hoppenbrouwer EJH, Nolte RJM, Drenth W, Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas, 1988, 107, 15–16. [Google Scholar]; c) Lindsey JS, Hsu H and Schreiman IC, Tetrahedron Lett. 1986, 27, 4969–4970. [Google Scholar]; d) Little RG, Longo FR and Varadi V, Inorg. Synth. 1976, 16, 213–220. [Google Scholar]; e) Treibs A and Haberle N, Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1968, 718, 183–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Laville I, Pigaglio S, Blais J-C, Doz F, Loock B, Maillard P, Grierson DS, Bliss J, J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 2558–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Williamson A, Philos. Mag, 1850, 37, 350–356. [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Singh S, Aggrawal A, Bhupathiraju NVSDK, Newton B, Nafees A, Gao R, Drain CM Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 6311–6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hirohara S, Obata M, Alitomo A, Shanyo K, Ando T, Tanihara M, Yano S, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biology. 2009, 97, 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Aicher D, Wiehe A, Stark CBW, Synlett. 2010, 3, 395–398. [Google Scholar]; d) Tomé JPC, Silva EMP, Pereira AMVM, Alonso CMA, Faustino MAP, Neves MGPMS, Tomé AC, Cavaleiro JAS, Tavares SAP, Duarte RR, Caeiro MF, Valdeiro ML, Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 4705–4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Tomé JPC, Neves MGPMS, Tomé AC, Cavaleiro JAS, Mendonça AF, Pegado IN, Duarte R, Valdeiro ML, Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 3878–3888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Mironov AF, Isaeva GM, Shvets VI, Evstigneeva RP, Stepanov AN, Perov AA, Kupriyanov Bioorg SE. Khim. 1978, 10, 1410–1413. [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Giuntini F, Bryden F, Daly R, Scanlan EM, Boyle RW, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 1203–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gomes MC, Silva S, Faustino MAF, Neves MGPMS, Almeida A, Cavaleiro JAS, Tomé JPC, Cunha AI, Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2013, 12, 262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gening ML, Titov DV, Cecioni S, Audfray A, Gerbst AG, Tsvetkov YE, Krylov VB, Imberty A, Nifantiev NE, Vidal S, Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19, 9272–9285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Cecioni S, Matthews SE, Blanchard H, Praly J-P, Imberty A, Vidal S, Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 356, 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Cecioni S, Praly J-P, Matthews SE, Wimmerova M, Imberty A, Vidal S, Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18(20), 6250–6263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Daly R, Vaz G, Davies AM, Senge MO, Scanlan EM, Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18, 14671–14679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Garcia G, Naud-Martin D, Carrez D, Croisy A, Maillard P, Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 4924–4932. [Google Scholar]; h) Locos OB, Heindl CC, Corral A, Senge MO, Scanlan EM, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar]; i) Hao E, Hensen TJ, Vincente MGH, J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2009, 13, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mukosera GT, Adams TP, Rothbarth RF, Langat H, Barkley RG, Akanda S, Dolewski RD, Ruppel JV, Snyder NL, Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Silva AMG, Tomé AC, Neves MGPMS, Silva AMS, Cavaleiro JAS, Perrone D, Dondoni A, Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 603–605. [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Grin MA, Lonin IS, Lakhina AA, Ol’shanskaya ES, Makarov AI, Sebyakin YL, Guryeva LY, Toukach PV, Kononikhin AS, Kumin VA, Mironov AF, J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2009, 13, 336–345. [Google Scholar]; b) Grin MA, Lonin IS, Likhosherstov LM, Novikova OS, Plyutinskaya AD, Plotnikova EA, Kachala VV, Yakubovskaya RI, Mironov AF, J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2012, 16, 1094–1109. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Moan J, Berg K, Photochem. Photobiol. 1991, 53, 549–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cooper SLA, Graepel KW, Steffens RC, Dennis DG, Cambronero GE, Wiggins R, Ruppel JV, Snyder NL, J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2019, 23, 850–855. [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Gou F, Jiang X, Fang R, Jing H, Zhu Z, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 6697–6703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lin VS, DiMagno SG, Therien MJ, Science 1994, 264, 1105–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) DiMagno SG, Lin VS, Therien MJ, J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 5983–5993. [Google Scholar]; b) Gao G-Y, Ruppel JV, Allen DB, Chen Y, Zhang XP, J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 9060–9066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Eisner U, Harding MJCJ, Chem. Soc. 1964, 4089–4101. [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Zemplén G, Pacus E, Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1929, 62, 1613–1614. [Google Scholar]; b) Zemplén G, Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1927, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Kim H-J, Lindsey JS, J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 5475–5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fan D, Taniguchi M, Lindsey JS, J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 5350–5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Krayer M, Ptaszek M, Kim H-J, Meneely KR, Fan D, Secor K, Lindsey JS, J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1016–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chen C-Y, Sun E, Fan D, Masahiko T, McDowell BE, Yang E, Diers JR, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS, Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 9443–9464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].a) Boden S, Reise F, Kania J, Lindhorst TK, Hartmann L, Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 1800425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bücher KS, Yan H, Creutznacher R, Ruoff K, Mallagaray A, Grafmüller A, Dirks JS, Kilic T, Weickert S, Rubailo A, Drescher M, Schmidt S, Hansman G, Peters T, Uetrecht C, Hartmann L, Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 3714–3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Broecker MF, Hanske J, Martin CE, Baek JY, Wahlbrink A, Wojcik F, Hartmann L, Rademacher C, Anish C, Seeberger PH, Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].a) Jadhav S, Cheng-Bin Y, Rojander J, Grönroos TJ, Solin O, Virta P, Bioconjugate Chem. 2016, 27(4), 1023–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lovell JF, Chen J, Huynh E, Jarvi MT, Wilson BC, Zheng G, Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21(6), 1023–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lovell JF, Jin H, Ng KK, Zheng G, Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. 2010, 49, 7917–7919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ponader D, Wojcik F, Beceren-Braun F, Dernedde J, Hartmann L, Biomacromolecules. 2012, 13, 1845–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.