Abstract

Objectives:

Obtaining informed consents from older adults is surrounded by many ethical and practical challenges. The objective of this study was to evaluate ethical issues and strategies in consenting older adults in Jordan as perceived by academic researchers and older adults.

Methods:

An anonymous questionnaire was distributed to academic researchers in the Jordanian health sciences colleges, and a sample of older adults. The study survey included items eliciting demographics, professional characteristics, and perceptions regarding the consenting process in older adults, consent-related skills in elderly, and strategies to improve the consenting process in older adults. The survey was then modified to assess the consent-related ethical issues and challenges as viewed by a sample of older adults after explaining the concept of the consenting process to them.

Key findings:

A total of 250 academic researchers and 233 older adults participated in the study. Both researchers and older adults reported that having to sign the written forms and the impact of age-related physical impairments were the most challenging obstacles when consenting older adults. Lack of consistency and repeating questions were the most frequently encountered obstacles by researchers in consenting older adults. Ensuring privacy (anonymity/confidentiality), dedicating more time for the consenting process, treating older adults as autonomous individuals and respecting their cultural beliefs were the most helpful strategies recommended by both academic researchers and older adults.

Conclusions:

Obtaining informed consents from older adults is a challenging process. Researchers should be aware of the special needs and strategies to achieve realistic and ethical informed consents from older adults.

Keywords: Ethics, consent process, academic researchers, older adults, Jordan

Introduction

The world population is aging constantly1. Considering the unique needs of aging populations, health care practices should be customized to meet older adult needs. For example, evidence-based health services provided to older adults should be based on research conducted specifically on older adult populations. However, elderly-based research is still inadequate and less illustrative compared to research involving younger populations2, 3. One of the important factors leading to underrepresentation of older adults in clinical, social and behavioral research is the difficulty associated with obtaining informed consents from older adult individuals2, 4, 5. In addition, obtaining informed consents from older adults is confined by many ethical and practical challenges, and therefore, it is much more than obtaining a signature. For instance, receiving adequate information, comprehending the information, and then making a voluntary decision are essential components of the process of providing an informed consent6, 7.

Health challenges associated with aging such as hearing and vision impairments, as well as diseases and weakness, can impact the validity and flow of the consenting process in older adults. Both the amount of information and how fast it is delivered to potential participants can influence their comprehension, and consequently, can influence their willingness to participate in research projects8, 9. Limited response time, speaking difficulties, barriers to seeking further information, level of emotional stability and control, cognitive impairment, and medication use are other factors that might influence the consenting process8–11.

Clinical, social and behavioral research practices and outcomes depend largely on researchers’ training and ethical competence. For example, consenting process that conforms to pertinent ethical principles in research is mandatory to produce valid data. In addition, data quality can be enhanced by respecting the right to autonomy of each potential participant without any explicit or implicit coercion7, 9, 12. Overall, researcher interaction with participants is the main determinant of the validity and quality of the informed consent13. Ethical challenges surrounding the consenting process in clinical, social and behavioral research with older adults are still understudied. More research is needed to raise awareness and to explore strategies that could better facilitate and organize the consenting process in order to produce valid and reliable research outcomes. This study aimed to evaluate perceptions regarding the consenting process and strategies to improve the consenting process in older adults as perceived by both academic researchers as well as older adults. In addition, this study aimed to evaluate consent-related skills deficiencies and problems faced by researchers during the consenting process in older adults.

Methods

Design and Procedures

This research was based on a cross-sectional survey that utilized a structured questionnaire to interview participants and collect data. Academic researchers in six health sciences schools (medicine, pharmacy, nursing, dentistry, public health, and applied medical sciences) in Jordan were approached and asked about their willingness to participate in the study by completing a survey. Eligibility criteria included being adult (≥18 years old) and having ever conducted clinical, social and behavioral research with older adult population in the past. Eligibility was determined at the interview time. The interviewer has approached all academic staff in all Jordanian public and private universities between July 1, 2017 and November 30, 2017. Within the same period, a sample of older adults was recruited and interviewed at King Abdullah University Hospital outpatient clinics. Eligibility criteria included being older adult (≥ 65 years old), independent and cognitively intact as perceived by the interviewer. Interviewees were presented with a hypothetical scenario of the consenting process. Additionally, they were presented with a number of statements on the consenting process and were asked to indicate whether they agree or disagree with each statement. Perceptions about the consenting process and strategies that may potentially improve the process were assessed based on the view of these older adult participants.

Instrument

The study instrument was composed of 46 items that measured demographics and professional characteristics, as well as perceptions regarding a number of issues. These issues included designing consent forms, the consenting process in older adults, consent-related skills in elderly, and strategies to improve the consenting process in older adults. The survey draft was reviewed by five faculty members who were expert in survey research methods from one of the universities in Jordan. These experts were asked to comment on the overall flow of the survey, as well as on the wording and content of every item. Their feedback were used to revise, improve and produce the final version of the survey. Another shortened version of the survey was utilized (after removing researcher-related sections)to assess the consent-related ethical issues and challenges as viewed by a sample of older adults.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to summarize the sample basic characteristics. The results of these analyses are presented in terms of frequencies and percentages. Perceptions and views regarding consenting process in older adults and strategies to improve the consenting process were presented as percentages of responders who agreed/disagreed with relevant statements. Average weighted scores were calculated by adding up each agreement level (1 to 5) multiplied by the respondent proportion for each level. Frequencies of encountered deficiencies/difficulties in skills needed for effective consenting process in older adults were assessed based on researchers’ experiences (1 = never; 5 = always). The weighted frequency score for each skill deficiency was calculated by adding up each frequency level (1 to5; 1 = never; 5 = always) multiplied by proportion of respondents who encountered that level of deficiency. Finally, a question was directed to evaluate challenges in the current consenting process with older adults as viewed by academic researchers. Challenges’ percentages of the total number of reported challenges frequencies were calculated. Data were analyzed using STATA version 1414.

Ethical considerations

This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee at Jordan University of Science and Technology/King Abdullah University Hospital (18/106/2017). Participants were informed about the goal of the study as well as the intended use and expected values of the results. Participant’s confidentiality was ensured using anonymous data collection process. Participation consent was implied as participants agreed to fill the survey out. The principal investigator was the only person who had an access to the data.

Results

A total of 250 academic researchers participated in the study with a response rate of 74%, all of them were involved directly in research with patients aged 65 years or older. The majority of these participants were from public universities (89.6%), aged 45 years old or younger(64%), males (54%) and married (79.6%). About half of the researchers were either assistant or associate professors (58.8%), and 33.6%, 20.8% and 22.8% were from medical, nursing and pharmacy schools, respectively. Out of all academic research participants, 30% reported that they had published 1–5 articles and 76.4% reported that they have been involved in 1–4 research projects in older adult population. More than half (65.5%)of participants received formal training in ethics. The demographic and professional characteristics of these participants are detailed in Table 1A. A total of 233 older adults were interviewed, of whom 58% were males, 84% were married, 48% were either employed or retired and 37% reported having at least college education. Older adult characteristics are detailed in Table 1B.

Table 1A:

Demographics and Professional Characteristics of Academic Researcher Respondents in Jordan.(Numbers, Percentages)

| Character | n (total =250) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <30 | 58 | 23.2 |

| 30–45 | 100 | 40.0 |

| 46–60 | 55 | 22.0 |

| >60 | 34 | 13.6 |

| (Missing data) | 3 | 1.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 115 | 46 |

| Male | 135 | 54 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 199 | 79.6 |

| Single | 32 | 12.8 |

| Widowed | 10 | 4 |

| Divorced | 9 | 3.6 |

| Academic institution | ||

| Public | 224 | 89.6 |

| Private | 26 | 10.4 |

| School | ||

| Applied medical sciences | 21 | 8.4 |

| Dentistry | 35 | 14 |

| Medicine | 84 | 33.6 |

| Nursing | 52 | 20.8 |

| Pharmacy | 57 | 22.8 |

| Public health | 1 | 0.4 |

| Academic rank | ||

| MS | 64 | 25.7 |

| Assistant Professor | 95 | 38 |

| Associate Professor | 52 | 20.8 |

| Professor | 39 | 15.6 |

| Number of years in current position | ||

| 1–3 | 127 | 50.8 |

| 4–7 | 81 | 32.4 |

| >7 | 42 | 16.8 |

| Number of published articles | ||

| None | 65 | 26 |

| 1–5 | 75 | 30 |

| 6–10 | 35 | 14 |

| 11–20 | 41 | 16.4 |

| >20 | 34 | 13.6 |

| Frequency of research in elderly | ||

| Once | 111 | 44.4 |

| 2–4 | 80 | 32 |

| 5–10 | 32 | 12.8 |

| >10 | 27 | 10.8 |

| Ethics training | ||

| YES | 164 | 65.6 |

| No | 86 | 34.4 |

Table 1B:

Demographics of Older Adults Respondents in Jordan.(Numbers, Column Percentages)

| Character | n (total =233) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age>=65 | 233 | 100 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 98 | 42 |

| Male | 135 | 58 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 196 | 84 |

| Single | 4 | 2 |

| Widowed | 15 | 6 |

| Divorced | 18 | 8 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 78 | 33 |

| Unemployed | 120 | 52 |

| Retired | 35 | 15 |

| Nationality | ||

| Jordanian | 203 | 87 |

| Others | 30 | 13 |

| Education | ||

| College and over | 86 | 37 |

| High school | 78 | 33 |

| Junior school or lower | 69 | 30 |

Regarding the current practice related to developing and designing consent forms, 66% of researchers reported that consent forms are typically developed by trained investigators whereas29.2% reported using previously developed consent form templates. Among academic researcher participants, 65.6% were satisfied with the way consent forms are developed and applied in current practice, and 77.5% agreed that patients should be approached before developing the consent form as their input is important to consider when developing such forms.

Table 2A describes researchers’ perceptions regarding challenges associated with the consenting process in older adults. Signing the written forms (as opposed to verbally consenting to participate), health challenges associated with aging (e.g., hearing impairment), and understanding their right to refuse to participate were the most perceived challenges in the consenting process according to academic researchers(average scores were 4.17, 3.69 and 3.37, respectively, on a scale from 1 [lowest difficulty] to 5 [highest difficulty]). In agreement with researchers’ views, the vast majority of older adults agreed that providing verbal consent is less stressful than signing the written forms (average score was 4.25on a scale from 1 [lowest difficulty] to 5 [highest difficulty]). As shown in Table 2B, older adults acknowledged the influence of health challenges associated with aging on the consenting process (average score was 3.55on a scale from 1 [lowest difficulty] to 5 [highest difficulty]).

Table 2A:

Perceptions of Researchers Regarding the Consenting Process in Older Adults.(Row Percentages)

| Strongly Disagree 1 | Disagree 2 | Neutral 3 | Agree 4 | Strongly Agree 5 | Averagea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adults in general have more difficulties in the consenting process compared to younger ages. | 0.8 | 39.2 | 8 | 48.8 | 3.2 | 3.14 |

| With aging, various physical changes can affect the process of informed consent. | 0 | 16.4 | 7.6 | 66.8 | 9.2 | 3.69 |

| Older adults may be suspicious of research because of feelings of vulnerability or previous experiences. | 0 | 26.4 | 34 | 33.6 | 6 | 3.19 |

| Older adults can be suspicious regarding the motives of the researcher. | 0.4 | 24 | 36.4 | 35.2 | 4 | 3.18 |

| Obtaining verbal consent is less stressful than signing the written forms. | 0.8 | 6 | 7.2 | 47.6 | 38.4 | 4.17 |

| Many older adults have difficulties in understanding their right to refuse. | 0.8 | 24 | 20 | 48 | 7.2 | 3.37 |

| Older adults often have concerns about confidentiality of information and anonymity. | 1.2 | 30 | 36.8 | 28.8 | 3.2 | 3.03 |

| Older adults often see their autonomy threatened when researchers often look to caregivers for informed consent. | 0.8 | 24 | 40.8 | 30.4 | 4 | 3.13 |

The average score for each perception was calculated by adding up each agreement level (1 to 5) multiplied by the respondent percentage for each level.

Table 2B:

Perceptions of Older Adults Regarding the Consenting Process.(Row Percentages)

| Strongly Disagree 1 | Disagree 2 | Neutral 3 | Agree 4 | Strongly Agree 5 | Averagea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adults in general have more difficulties in the consenting process compared to younger ages. | 0.4 | 52.8 | 1.3 | 43.3 | 2.2 | 2.94 |

| With aging, various physical changes can affect the process of informed consent. | 0 | 23.6 | 0.8 | 73 | 2.6 | 3.55 |

| Older adults may be suspicious of research because of feelings of vulnerability or previous experiences. | 0 | 41.2 | 29.6 | 27.5 | 1.7 | 2.90 |

| Older adults can be suspicious regarding the motives of the researcher. | 0 | 39 | 29 | 30 | 2 | 2.95 |

| Obtaining verbal consent is less stressful than signing the written forms. | 0 | 2 | 0 | 69 | 29 | 4.25 |

| Many older adults have difficulties in understanding their right to refuse. | 2 | 58 | 7.3 | 31.8 | 0.9 | 2.72 |

| Older adults often have concerns about confidentiality of information and anonymity. | 0.9 | 48.9 | 22.3 | 27 | 0.9 | 2.78 |

| Older adults often see their autonomy threatened when researchers often look to caregivers for informed consent. | 0.4 | 43.8 | 27.9 | 27 | 0.9 | 2.84 |

The average score for each perception was calculated by adding up each agreement level (1 to 5) multiplied by the respondent percentage for each level.

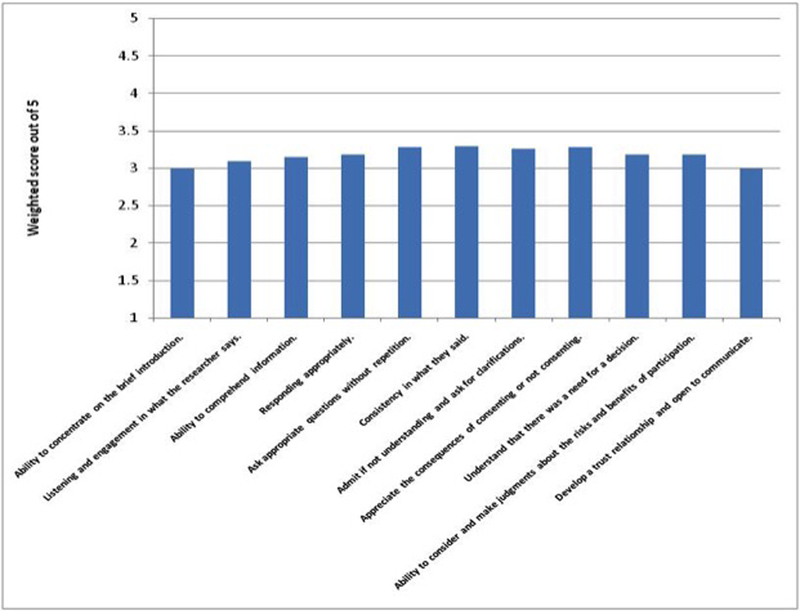

Figure 1 demonstrates the levels of perceived deficiencies in consenting-related skills as seen by researchers involved in clinical, social and behavioral research with older adults. Lack of consistency, requesting survey questions to be repeated and limited understanding of the consequences of consenting (or consequences of refusing to consent) were the most frequently encountered challenges in this population(average scores were 3.3, 3.28 and 3.28, respectively, on a scale from 1 [lowest difficulty] to 5 [highest difficulty]).

Figure1: Consent-related Skills Deficiencies in Older Adults as Viewed by Researchers.

Frequencies of encountered deficiencies/difficulties in skills needed for effective consenting process in older adults based on researchers’ experiences (1 = never; 5 = always). The weighted frequency score for each skill was calculated by adding up each frequency level (1 to5; 1 = never; 5 = always) multiplied by the respondent percentages who encountered that level of deficiency.

Researchers’ agreement levels with suggested strategies to improve the consenting process in older adults are demonstrated in Table 3A. Ensuring anonymity/confidentiality, verbal reiteration and explanation of written material, dedicating more time and effort for the consenting process, treating older adults as autonomous individuals and respecting their cultural beliefs by using an appropriate language were the most helpful strategies as seen by academic researchers(average scores were 4.48, 4.32, 4.3, 4.27 and 4.26, respectively, on a scale from 1 [Least important] to 5 [Most important]). Consistent with researcher views, older adults advocated the importance of anonymity/confidentiality in communication, dedicating more time and effort for consenting process consenting process, being treated as autonomous individuals and respecting their cultural beliefs (average scores were 4.55, 4.52, 4.51 and 4.49, respectively on a scale from 1 [Least important] to 5 [Most important]). More details are shown in Table 3B.

Table 3A:

Perceptions of Researchers Regarding Strategies to Improve the Consenting Process in Older Adults.(Row Percentages)

| Strongly Disagree 1 | Disagree 2 | Neutral 3 | Agree 4 | Strongly Agree 5 | Averagea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparing easy-to-read language &short document. | 0 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 71.6 | 25.2 | 4.21 |

| Consent form tailored with a low reading level and a large typing font | 0 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 72.4 | 24 | 4.20 |

| Written material should be supplemented with verbal reiteration and explanation. | 0 | 0.8 | 6.4 | 52.8 | 40 | 4.32 |

| Explaining that the research is independent of service delivery and in no way affects their care. | 1.6 | 3.2 | 7.6 | 56 | 31.6 | 4.13 |

| The respondents who were willing to sign the consent form should be asked to do so at the end of the interview (rather than at the beginning). | 11.6 | 21.6 | 13.2 | 38.4 | 15.2 | 3.24 |

| Informers should utilize a language that is respectful of their cultural beliefs. | 1.2 | 0.4 | 5.6 | 57.2 | 35.6 | 4.26 |

| Older adults should be valued as autonomous individuals; should not be treated as kids. | 2 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 53.2 | 39.6 | 4.27 |

| Having older adults paraphrase what they are told to determine whether they understand the disclosed information. | 0 | 2.4 | 8 | 60.4 | 29.2 | 4.16 |

| Being prepared that seeking consent from older individuals usually requires extra time and effort. | 0 | 1.6 | 7.6 | 50.4 | 40.4 | 4.30 |

| Being prepared that sometimes more than one short session might be needed for patients to absorb and understand the research issue. | 0 | 2.8 | 6.8 | 58.4 | 32 | 4.20 |

| Consider privacy when communicating information and evaluating decision capacity. | 0 | 0.4 | 4.8 | 41.6 | 53.2 | 4.48 |

The average score for each strategy was calculated by adding up each agreement level (1 to 5) multiplied by the respondent percentage for each level.

Table 3B:

Perceptions of Older Adults Regarding Strategies to Improve the Consenting Process in Older Adults.(Row Percentages)

| Strongly Disagree 1 | Disagree 2 | Neutral 3 | Agree 4 | Strongly Agree 5 | Averagea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparing easy-to-read language &short document. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 68.7 | 31.3 | 4.31 |

| Consent form tailored with a low reading level and a large typing font | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 66.1 | 33.5 | 4.33 |

| Written material should be supplemented with verbal reiteration and explanation. | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 57.1 | 42 | 4.41 |

| Explaining that the research is independent of service delivery and in no way affects their care. | 0.8 | 11.2 | 4.3 | 52.8 | 30.9 | 4.02 |

| The respondents who were willing to sign the consent form should be asked to do so at the end of the interview (rather than at the beginning). | 14.2 | 42.5 | 14.2 | 22.7 | 6.4 | 2.65 |

| Informers should utilize a language that is respectful of their cultural beliefs. | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 50.2 | 49.4 | 4.49 |

| Older adults should be valued as autonomous individuals; should not be treated as kids. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49.4 | 50.6 | 4.51 |

| Having older adults paraphrase what they are told to determine whether they understand the disclosed information. | 0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 66 | 32.2 | 4.30 |

| Being prepared that seeking consent from older individuals usually requires extra time and effort. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48.1 | 51.9 | 4.52 |

| Being prepared that sometimes more than one short session might be needed for patients to absorb and understand the research issue. | 0 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 65.2 | 33.5 | 4.31 |

| Consider privacy when communicating information and evaluating decision capacity. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45.1 | 54.9 | 4.55 |

The average score for each strategy was calculated by adding up each agreement level (1 to 5) multiplied by the respondent percentage for each level.

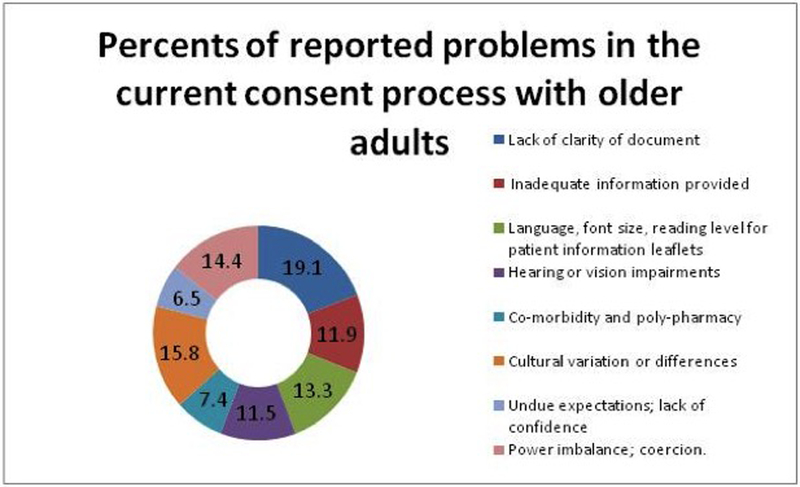

Overall, use of complex medical terminology, high readability level text, small font size, cultural variation and power imbalance were the most common challenges in the current consenting process with older adults as viewed by academic researchers (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

The Most Common Problems in the Current Consent Process with Older Adults as Viewed by Researchers

Discussion

Even though concepts related to informed consents are well discussed in the literature, these concepts are understudied in cognitively intact older adults. This study highlighted the most common challenges in the consenting process and the potential strategies to improve it in research involving older adults. It is noteworthy that major challenges and suggested improvement strategies perceived by older adults were very consistent with those perceived by researchers. Both groups advocated that signing the written forms and the health challenges (e.g., hearing impairment)associated with aging were the most pressing challenges when consenting older adults. In terms of encountered health challenges among older adults in practice, researchers reported lack of consistency and having to repeat questions multiple times as the most frequently encountered challenges. Academic researchers as well as older adults consistently agreed about potential strategies that can be undertaken to improve the consenting process, including protecting participants’ anonymity or confidentiality, allowing more time and dedicating more effort to the consenting step, treating older adults as autonomous individuals and respecting their cultural beliefs.

Obtaining written signatures from older adults was perceived as the most significant challenge in consenting older adults by both researchers and older adults themselves. Therefore, certain measures could be taken to mitigate the stress associated with providing a written signature, leading to a smoother and more productive consenting process. The findings indicated that older adults tend to view any signed document as a contract, and therefore, they tend to be more hesitant regarding signing such a document15. Thus, having the consent in a non-contract format might be helpful, for example, using pastel paper with a casual font16. In addition, previous literature had suggested providing alternatives to written signature such as stamping, thumb-printing, nodding, and handshaking17. Such alternatives may be considered in future research contingent upon approval by Institutional Review Boards (IRB) in academic and research institutions. Findings from this study were consistent with previous research, indicating that such alternatives could make it easier for older people to participate in research through relieving any stress associated with providing a written signature.

Various age-related health changes such as hearing, vision and speaking impairments, co-morbid illnesses, cognitive impairments and personal/emotional vulnerabilities were shown to impact the process and outcomes of the consenting process9. This was in agreement with results from this study that emphasized the influence of age-related health changes on the process of informed consent in older adults. Matching target population capabilities in light of participants’ abilities and age-related physical frailty is a very important consideration when obtaining informed consents from older adults2. Moore et al. advocated that information should be disclosed at the appropriate level of the target population in relation to education, maturation, language, age, and cognitive ability18. Impairment in hearing and vision may impact older adults’ ability to listen, read, and comprehend study risks and benefits, and therefore, impact their ability to provide a fully informed consent19. The results of this study were consistent with previous research. Therefore, our findings suggest that future researchers investigating older adults may consider carefully designing the consenting process to match potential participants’ physical and behavioral capabilities.

In this study, academic researchers who participated in the study highly agreed that older adults are less likely to understand their right of informed refusal to participate in research studies. Compared to younger adults, older adults in general are more likely to think of health care providers as trustworthy. Therefore, older adults may be less likely to refuse a request to participate in research and to appreciate the consequences of refusal15, 19, 20. In addition, older adults may participate in research studies because they feel powerless, mainly due to emotional distress, vulnerability and minimal social support15, 21. Such feelings might be subtle to older adults but can be sensed by experienced researchers.

Inconsistency in older adults’ responses and the need to repeat questions multiple times were the most encountered challenges by researchers. Although this paper evaluates the consenting process among cognitively intact older adults (e.g., individuals without dementia), the impact of aging per se on cognitive function especially with regard to memory, learning and information processing capabilities are undeniable22. Deficit in short-term memory is strongly associated with aging and was shown to critically impact information comprehension during the consenting process23.

In this study, paying more attention to anonymity/confidentiality when communicating with older adults, especially when evaluating their ability to make decisions, was found to be the most important strategy in provoking an effective and respectful consenting process. Interestingly, considering privacy by maintaining anonymity/confidentiality was the most agreed upon strategy by researchers and older adults themselves to facilitate the informed consenting process. Heath et al. emphasized the importance of maintaining older adults privacy and dignity in the consenting process9. Interviewing older adults in a private setting would enhance their desire to ask questions and request certain information to be repeated before making a decision regarding the consenting process. Furthermore, privacy is needed when evaluating elderly decision-making capacity as they prefer one-to-one conversation when they interact with researchers. This may give them the freedom to refuse to participate in research without feeling coerced or embarrassed.

Besides privacy, there was a high level of agreement among researchers’ and older adults’ responses regarding the importance of expecting to dedicate more time and effort in order to obtain a valid informed consent from older adults. With deficit in short term memory associated with aging, granting older adults more time to make a decision regarding participating in research is a crucial step that aims to address comprehension obstacles and to support autonomous consent23. Respecting cultural beliefs was another highly agreed upon strategy that facilitates effective communication and establishes the needed trust and openness to communicate between participants and researchers. Cultural competence was shown to be an essential strategy in provoking an informed consent from older people by building trust and overcoming cultural differences and language barriers8.

In the current study, more than a third of the researchers did not have a training in research ethics. Inadequate research ethics training was demonstrated in several studies conducted in developing countries24–26. A survey of the faculty members at Cairo University in Egypt showed that almost half of them never attended a course in research ethics27. Giving the gaps in research ethics in the Middle East countries26, It is clear that research ethics training is necessary to improve ethical standards in the conduct of academic and biomedical research.

Conclusions

The findings of this study highlight the importance of considering age-related physical and emotional characteristics in the consenting process, and so no one size consent can fit all ages. In sum, as a public policy implication, this study underscores the need for raising awareness and better educating clinical, social and behavioral investigators about special needs and strategies that pertain to obtaining valid and ethical informed consents from older adults.

Funding:

Work on this project was supported by grant # 5R25TW010026-02 from the Fogarty International Center of the U.S. National Institutes of Health on behalf of the Research Ethics Program in Jordan.

Footnotes

Ethics approval: This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee at Jordan University of Science and Technology/King Abdullah University Hospital.

Conflict of interest

The Author(s) declare(s) that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Bergman H, Karunananthan S, Robledo LM, et al. Understanding and meeting the needs of the older population: a global challenge. Canadian geriatrics journal : CGJ 2013; 16: 61–65. DOI: 10.5770/cgj.16.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barron JS, Duffey PL, Byrd LJ, et al. Informed consent for research participation in frail older persons. Aging clinical and experimental research 2004; 16: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherjee A, Livinski AA, Millum J, et al. Informed consent in dental care and research for the older adult population: A systematic review. Journal of the American Dental Association 2017; 148: 211–220. DOI: 10.1016/j.adaj.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayer A and Tadd W. Unjustified exclusion of elderly people from studies submitted to research ethics committee for approval: descriptive study. Bmj 2000; 321: 992–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugarman J, McCrory DC and Hubal RC. Getting meaningful informed consent from older adults: a structured literature review of empirical research. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1998; 46: 517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pullman D. Subject comprehension, standards of information disclosure and potential liability in research. Health law journal 2001; 9: 113–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nijhawan LP, Janodia MD, Muddukrishna BS, et al. Informed consent: Issues and challenges. Journal of advanced pharmaceutical technology & research 2013; 4: 134–140. DOI: 10.4103/2231-4040.116779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jong-Ni Lin K-M C. Cultural Issues and Challenges of Informed Consent in Older Adults. Tzu Chi Nursing Journal 2007; 6: 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heath H. Communicating with older people … (continuing education credit). Nursing standard 1997; 11: 48–54; quiz 55–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson FL, Racine E, Tekieli V, et al. Literacy, readability and cultural barriers: critical factors to consider when educating older African Americans about anticoagulation therapy. Journal of clinical nursing 2003; 12: 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pape T. Legal and ethical considerations of informed consent. AORN journal 1997; 65: 1122–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Provencher V, Mortenson WB, Tanguay-Garneau L, et al. Challenges and strategies pertaining to recruitment and retention of frail elderly in research studies: a systematic review. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics 2014; 59: 18–24. DOI: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanjari M, Bahramnezhad F, Fomani FK, et al. Ethical challenges of researchers in qualitative studies: the necessity to develop a specific guideline. Journal of medical ethics and history of medicine 2014; 7: 14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawton MP. Do elderly research subjects need special protection? psychological vulnerability. IRB 1980; 2: 5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kavanaugh K, Moro TT, Savage T, et al. Enacting a theory of caring to recruit and retain vulnerable participants for sensitive research. Research in nursing & health 2006; 29: 244–252. DOI: 10.1002/nur.20134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen KM, Lin JN, Lin HS, Wu HC, Chen WT, & Li CH, et al. Use of the Simplified Tai-Chi Exercise Program to promote the physical health of the institutionalized elders. Paper session presented at the 16th International Nursing Research Congress, Waikoloa, Hawaii. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore L and Savage J. Participant observation, informed consent and ethical approval. Nurse researcher 2002; 9: 58–69. DOI: 10.7748/nr2002.07.9.4.58.c6198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abernethy DR and Azarnoff DL. Pharmacokinetic investigations in elderly patients. Clinical and ethical considerations. Clinical pharmacokinetics 1990; 19: 89–93. DOI: 10.2165/00003088-199019020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Getz K, Borfitz D and Gelsinger P. Informed consent : a guide to the risks and benefits of volunteering for clinical trials. Boston, MA: Thomson/CenterWatch, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers AC. Vulnerability, health and health care. Journal of advanced nursing 1997; 26: 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffiths MA and Harmon TR. Aging Consumer Vulnerabilities Influencing Factors of Acquiescence to Informed Consent. JOCA Journal of Consumer Affairs 2011; 45: 445–466. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rempusheski VF. Elements, perceptions, and issues of informed consent. Applied nursing research : ANR 1991; 4: 201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atallah D, Moubarak M, El Kassis N, et al. Clinical research ethics review process in Lebanon: efficiency and functions of research ethics committees - results from a descriptive questionnaire-based study. Trials 2018; 19: 27 DOI: 10.1186/s13063-017-2397-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikravanfard N, Khorasanizadeh F and Zendehdel K. Research Ethics Education in Post-Graduate Medical Curricula in I.R. Iran. Developing world bioethics 2017; 17: 77–83. DOI: 10.1111/dewb.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman H, Edwards H, Shamoo A, et al. Enhancing research ethics capacity in the Middle East: experience and challenges of a Fogarty-sponsored training program. Journal of empirical research on human research ethics : JERHRE 2013; 8: 40–51. DOI: 10.1525/jer.2013.8.5.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asem NSH. Perspectives of faculty at Cairo Universitiy towards research ethics and informed consent [abstract]; Presented at PRIM&R Conference; Nashville, TN: 2009. [Google Scholar]