Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 causes blood hypercoagulability and severe inflammation resulting in an increased risk of thrombosis. Consequently, COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular disease seem to be at higher risk of adverse events. Mondor’s disease is a rare, generally self-limiting, thrombosis of the penis. The pathogenesis of Mondor’s disease is unknown, and it is usually diagnosed through clinical signs and with Doppler ultrasound evaluation. We describe the case of a young man with COVID-19 infection who manifested Mondor’s disease.

LEARNING POINTS

SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with an inflammatory response leading to a prothrombotic state and subsequent risk of arterial and venous pathology.

Superficial vein thrombosis can occur in COVID-19 patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, vein thrombosis, Mondor’s disease

INTRODUCTION

SARS-CoV-2 infection was declared a pandemic in March 2020 [1]. COVID-19 can cause pneumonia leading to severe respiratory failure requiring intensive care, and also has serious implications for the cardiovascular system [1, 2].

Preliminary reports have shown that SARS-CoV-2 causes blood hypercoagulability and severe inflammation, resulting in an increased risk of thrombosis. Consequently, COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular disease seem to be at higher risk of adverse events [3–8].

Mondor’s disease is a rare, generally self-limiting, thrombophlebitis of the superficial veins of the penis (incidence <1.5%) [9–12]. The pathogenesis of Mondor’s disease is unknown, and it is usually diagnosed through clinical signs and with Doppler ultrasound evaluation[9–12]. We describe the case of a young man with COVID-19 infection who manifested Mondor’s disease

CASE DESCRIPTION

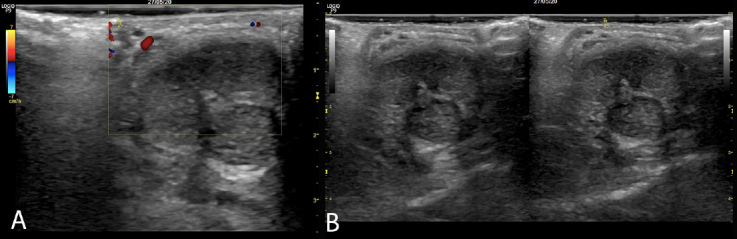

A 28-year-old male patient was admitted to the Emergency Unit complaining pain and had signs of inflammation in the middle third of his penis. The patient reported fever (38.5°C), cough and general distress over the previous 7 or 8 days. His medical history did not show any significant previous disease and he did not have any risk factors for cardiovascular disease. A chest x-ray was negative for pneumonia. Peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 96% on room air. Blood tests showed haemoglobin 12.3 g/dl, white blood cells 3,460/mm3, platelets 175,000/mm3, C-reactive protein (high-sensibility) 23.20 mg/dl, D-dimer 3.25 g/l and fibrinogen 721 mg/dl. The urine test was normal. Physical examination showed a cord-like induration on the dorsal surface of the penis with locoregional oedema. Ultrasound evaluation revealed thrombosis of the dorsal superficial vein of the penis (Fig. 1). A nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 was taken and was positive. The patient was treated with enoxaparin (4000 IU once a day) and azithromycin for 30 days. After only 48 hours he experienced a significant reduction in pain, and showed complete resolution of all signs of thrombosis 30 days after beginning therapy.

Figure 1.

Colour Doppler ultrasound images showing thrombophlebitis of the superficial vein of the penis

DISCUSSION

SARS-CoV-2 infection generally causes a mild disease characterized by fever and cough [1, 2]. However, some 15% of patients develop severe disease requiring hospitalization and oxygen support, and about 5% of these require admission to the intensive care unit [1, 2]. Various data indicate that COVID-19 affects multiple systems including the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, neurological, haematopoietic and immune systems [1–8].

COVID-19 pneumonia induces immunological dysregulation and excessive inflammation, and is characterized by platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, enhanced thrombin generation and fibrin formation documented by a significant increase in D-dimers leading to consumption of natural coagulation inhibitors [3, 4, 13]. Emerging data reveal that SARS-CoV-2 infection is a risk factor for both arterial and venous thrombosis [4–8]. Several studies have shown that the incidence of symptomatic, objectively confirmed venous thromboembolism (VTE) in COVID-19 patients hospitalized in the ICU can reach 30–40% [8]. An early Chinese study [14] demonstrated that 25% of COVID-19 patients developed lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) without VTE prophylaxis.

A recent study by Klok et al. described pulmonary embolisms (PE) in 25 of 184 ICU patients with COVID-19 (13.6%), 72% of which were in central, lobar or segmental pulmonary arteries, despite standard dose pharmacological prophylaxis [15–16]. In Italy, Lodigiani et al. showed thromboembolic events (venous and arterial) in 7.7% of patients admitted with COVID-19, corresponding to a cumulative rate of 21% [17]. No data are available on the incidence of superficial vein thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 infection.

Mondor’s disease is a rare pathology with an incidence of 1.39%, and is generally found in patients between 21 and 70 years of age. The aetiology is rarely identified [9–12], but Mondor’s disease is associated with several conditions including infection, direct trauma, sexual activity, penis injection, cancer, other vein thrombosis, and a deficit of antithrombin III, Protein C and S [9–12]. There are some reports of surgical thrombectomy, but treatment generally includes anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparins and occasionally antibiotics, and treatment of the causal aetiology if identified [9–12].

Our clinical case underlines the fact that SARS-CoV-2 infection is strongly linked to an inflammatory process leading to a prothrombotic state and subsequent risk of arterial and venous pathology. Therefore, in COVID-19 positive patients, the physician must always maintain a high clinical suspicion regarding common and uncommon forms of thrombosis, even in subjects with few risk factors.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: The Authors declare that there are no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang C. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss P, Murdoch DR. Clinical course and mortality risk of severe COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1014–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30633-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Ardes D, Boccatonda A, Rossi I, Guagnano MT, Santilli F, Cipollone F, et al. COVID-19 and RAS: unravelling an unclear relationship. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(8):E3003. doi: 10.3390/ijms21083003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levi M, Thachil J, Iba T, Levy JH. Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(6):e438–e440. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiong TY, Redwood S, Prendergast B, Chen M. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1798–1800. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(18):2352–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon SD, Vardeny O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 27; doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes GD, Burnett A, Allen A, Blumenstein M, Clark NP, Cuker A, et al. Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):72–81. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02138-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mondor H. Tronculite sous-cutanèe subaigue de la paroi thoragigue antèro-lateral. Mem Acad Chir. 1939;65:1271–1278. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liden-Castro E, Pelayo-Nieto M, Ramirez-Galindo I, Espinosa-Perezgrovas D, Cornejio-Davila V, Rubio-Arellano E. Mondor disease: thrombosis of the dorsal vein of the penis. Urol Case Rep. 2018;19:34–35. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar B, Narag T, Radotra BD, Gupta S. Mondor’s disease of penis: a forgotten disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:480–482. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.014159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Mwalad M, Loertzer H, Wicht A, Fornara P. Subcutaneous penile vein thrombosis (penile Mondor’s disease): pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Urology. 2006;67:586–588. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endothelitis in Covid-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boccatonda A, Ianniello E, D’Ardes D, Cocco G, Giostra F, Borghi C, et al. Can lung ultrasound be used to screen for pulmonary embolism in patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia? Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7(7):001748. doi: 10.12890/2020_001748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, Cecconi M, Ferrazzi P, Sebastian T, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]