Abstract

Purpose

Diabetic’s patients are supposed to experience higher rates of COVID-19 related poor outcomes. We aimed to determine factors predicting poor outcomes in hospitalized diabetic patients with COVID-19.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included all adult diabetic patients with radiological or laboratory confirmed COVID-19 who hospitalized between 20 February 2020 and 27 April 2020 in Alborz province, Iran. Data on demographic, medical history, and laboratory test at presentation were obtained from electronic medical records. Diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was self-reported. Comorbidities including cancer, rheumatism, immunodeficiency, or chronic diseases of respiratory, liver, and blood were classified as “other comorbidities” due to low frequency. The assessed poor outcomes were in-hospital mortality, need to ICU care, and receiving invasive mechanical ventilation. Self-reported. Multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to quantify the predictors of in-hospital mortality from COVID-19 in patients with DM.

Results

Of 455 included patients, 98(21.5%) received ICU care, 65(14.3%) required invasive mechanical ventilation, and 79 (17.4%) dead. In the multivariate model, significant predictors of “death of COVID-19” were age 65 years or older (OR (95% CI): 2.0 (1.16–3.44), chronic kidney disease (CKD) (2.05 (1.16–3.62), presence of “other comorbidities” (2.20 (1.04–4.63)), neutrophil count ≥8.0 × 109/L)6.62 (3.73–11.7 ((, Hb level < 12.5 g/dl (2.05 (1.13–3.72) (, and creatinine level ≥ 1.36 mg/dl (3.10 (1.38–6.98)). (All p –values <0.05). Some of these factors were also associated with other assessed poor outcomes, e.g., need to ICU care or invasive mechanical ventilation.

Conclusion

Diabetic patients with age 65 years or older, comorbidity CKD, “other comorbidities”, as well as neutrophil count ≥8.0 × 109/L, Hb level < 12.5 g/dl, and creatinine level ≥ 1.36 mg/dl, were more likely to dead after COVID-19. Presence of hypertension and cardiovascular disease were associated with none of the poor outcomes.

Keywords: Diabetes, COVID-19, Mortality, Risk factor

Introduction

The coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) has become to a serious global public health challenge. So far, more than 5.3 million new cases and 342 thousand deaths of COVID-19 has reported worldwide [1]; the pandemic continues to expand despite intensive global preventive efforts. As with previous viral pandemics, [2] patients with underlying conditions are supposed to experience higher rates of COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality [3–5].

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most common underlying conditions found among patients with COVID-19 [6, 7]. Besides, the presence of DM has been associated with a higher risk of poor outcome in these patients [8–10]. However, up to our knowledge, a few previous studies intended to identify patients’ factors on initial presentation that could predict poor outcome in diabetic patients with COVID-19 [11].

Hence, the present study has attempted to ascertain factors associated with poor outcome in hospitalized diabetic patients with COVID-19.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

This retrospective study included all diabetic patients aged 18 years or older with COVID-19 hospitalized between 20 February 2020 and 27 April 2020 in the Alborz province, Iran. Clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed if patients met one of the two following criteria: I) a positive RT–PCR result, or II) a positive pulmonary abnormality on chest CT based on the radiological criteria of COVID-9 infection. We excluded patients who were still hospitalized (n = 19). Diabetes was ascertained through self-reporting.

Data collection

Demographic and clinical characteristics including age, gender, medical history, having any comorbidities, disease symptoms (caught, fever, shortness of breath, tiredness and lack of consciousness), O2 saturation and drug history (statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)) were collected at the first day of hospitalization. The asked comorbidities included hypertension, cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), cancer, chronic liver diseases, psychological disorder, chronic respiratory disease, asthma, thyroid dysfunction, immunodeficiency, autoimmune diseases, hematologic disease, and neurological disorder.

Laboratory testing

Laboratory parameters on admission (fasting blood glucose level, white blood cell count, lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, concentrations of aspartate and alanine transaminases (AST, ALT), hemoglobin (Hb), creatinine, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), albumin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), creatine phosphokinase (Cpk) and creatine kinase myocardial band (Cpk-MB) were collected.

Outcome

The primary outcome of this study was in-hospital mortality and poor outcomes including need to intensive care unit (ICU) and being ventilated during hospitalization in COVID-19 patients with diabetes. The study population was classified into two groups: discharged (survivors) or dead (non-survivors). Cured patients were discharged from hospital according to the following criteria: lack of fever for at least 72 h, clinical alleviation, and improvement in pulmonary abnormalities on chest CT imaging.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, mean (standard deviation (SD)) or median (interquartile range (IQR)), respectively for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables, were used to summarize demographic, clinical, and laboratory data of the cohort. Characteristics of survivors and non-survivors were compared using two-tailed t-tests, Mann–Whitney U tests or Chi-square tests.

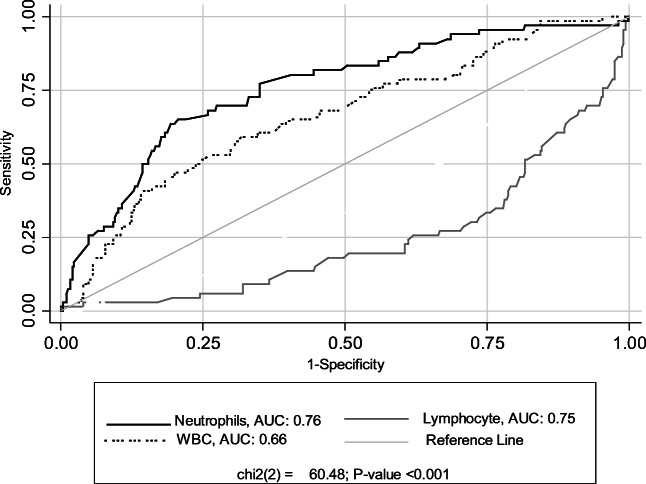

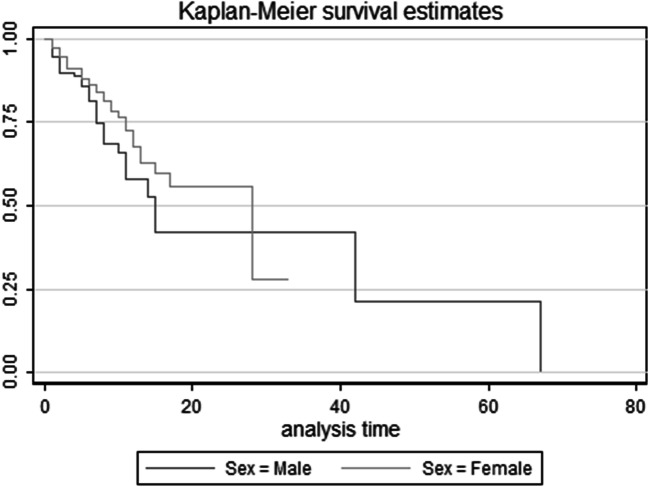

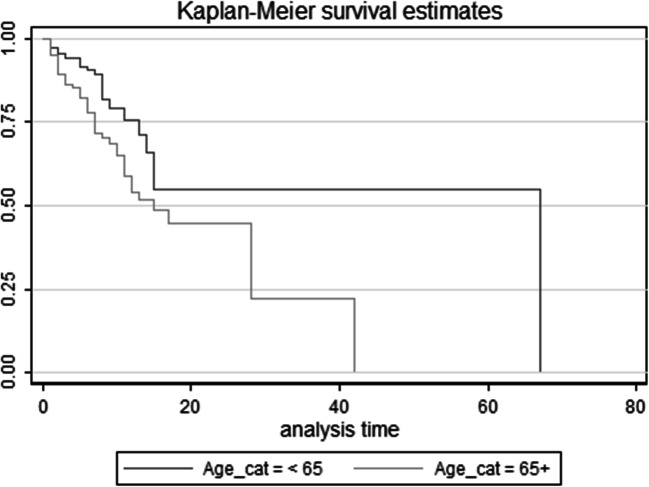

The receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis was performed to compare the predictive abilities of blood parameters for predicting death of COVID-19; area under the curve (AUC) and its 95% confidence interval (CIs) are presented. The optimal cut points that provided the maximum sensitivity and specificity for each blood parameter to predict death of COVID-19 were identified using the maximal Youden Index. Then, the blood parameters were converted into a binary variable based on these identified optimal outpoints. Univariable and Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess the association of predictor factors with each poor outcomes of COVID-19. Results are presented as crude and adjusted ORs and (95% CIs). We also performed a log-rank test to determine if there were differences in the survival distribution between males and females and two age groups ≥65 years and < 65 years.

We considered a P value of less than 0.05 as statistically significant. We conducted all statistical analyses using SPSS Version19.0, (SPSS Chicago, IL, USA) or STATA version11 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The study population was 455 hospitalized diabetic patients with COVID-19. Table 1 shows characteristics and disease-related symptoms in the study population on admission, overall and by survivor status. Overall, the mean age (SD) of patients was 63.8 (13.5), and 190 (41.8%) were male. The most common comlaints at prsentaion were shortness of breath (56.7%), caugh (45.9%), fever (37.4%), and tiredness (23.3%). At admission, lack of consciousness and O2 saturation less than 93% were observed in 5.7% (26) and 58.0% (264) of patients, respectively. Overall, 69.5% (316) of patients reported at least one comorbidity; the common comorbidities, in order of frequency, were HTN (54.0%), CVD (43.7%) and CKD (22.2%). The use of ACEIs /ARBs and statins was reported in 42.9% (190) and 28.9% (117) of patients, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics and disease-related symptoms in the study population on admission, overall and by survivor status

| Characteristics | Total N = 455 |

Non-survivors N = 79 |

Survivors N = 376 |

P –value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Mean (SD) | 63.8 (13.5) | 69.4 (12.2) | 62.6 (13.5) | < 0.001 |

| Age ≥ 65 years, % (N) | 47.9% (218) | 65.8% (52) | 44.1% (166) | < 0.001 |

| Gender: Male, % (N) | 41.8% (190) | 49.4% (39) | 40.2% (151) | 0.131 |

| Symptoms, % (N) | ||||

| Caught | 45.9% (209) | 36.7% (29) | 47.9% (180) | 0.070 |

| Fever | 37.4% (170) | 39.2% (31) | 37.0 (139) | 0.704 |

| Shortness of breath | 56.7% (258) | 62.0% (49) | 55.6% (209) | 0.294 |

| Tiredness | 23.3% (106) | 16.5% (13) | 24.7% (93) | 0.114 |

| Lack of consciousness, % (N) | 5.7% (26) | 16.5% (13) | 3.5% (13) | < 0.001 |

|

O2 saturation < 93% % (N) |

58.0% (264) | 88.6% (70) | 51.6% (194) | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities, % (N) | ||||

| HTN | 54.0% (239) | 60.5% (46) | 52.6% (193) | 0.206 |

| CVD | 43.7% (199) | 51.9% (41) | 42.0% (158) | 0.108 |

| CKD | 22.2% (101) | 35.4% (28) | 19.4% (73) | 0.002 |

| Other* | 10.1% (46) | 16.7% (13) | 8.8% (33) | 0.036 |

| Number of Comorbidities, % (N) | ||||

| 0 | 30.5% (139) | 22.8% (18) | 32.2% (121) | 0.008† |

| 1 | 25.7% (117) | 21.5% (17) | 26.6% (100) | |

| 2 | 29.5% (134) | 32.9% (26) | 28.7% (108) | |

| ≥ 3 | 14.3% (65) | 22.8% (18) | 12.5% (47) | |

| Drug History | ||||

| ACEIs or ARBs | 42.9% (190) | 50.0% (38) | 41.4% (152) | 0.169 |

| Statins | 28.9% (117) | 34.3% (24) | 27.8% (93) | 0.273 |

ACEIs angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARBs angiotensin II receptor blockers, CKD Chronic Kidney diseases, CVD Cardiovascular diseases, HTN Hypertension, IQR Inter quartile range, ICU Intensive care unit

*Cancer, rheumatism, immunodeficiency, or chronic diseases of respiratory, liver, and blood

†: linear-by-linear association test

During hospitalization, out of 455 patients, 98(21.5%) received ICU care, 65(14.3%) required invasive mechanical ventilation, and 79 (17.4%) dead. The median time from admission to discharge was 3 days (IQR: 1–6 days), and the median time to death was 4 days (2–8 days).

ompared to survivors, patients who dead (non-survivors) were significantly older (mean (SD) age: 69.4 years (12.2) vs. 62.6 years (13.5); P < 0.001), were more likely to have underlying comorbidity CKD (35.4% (28) vs. 19.4% (73); P = 0.002). In terms of numbers of comorbidities, a higher percentage of non-survivors had 3 or more comorbidities (22.8 vs. 12.5%; P = 0.008) than survivors.

Non-survivors were more likely to present with lack of consciousness (16.5% vs. 3.5%) and O2 saturation less than 93% (88.6% vs. 51.6%) than survivors. (Both p –values <0.001).

The frequency of the common complaints, ACEIs /ARBs and statins users, also the comorbidities HTN and CVD all were similar between survivors and non-survivors. (All p –values >0.05).

Laboratory findings on admission of the study population are presented in Table 2, overall and by survivor status. A lower lymphocyte count (median (IQR): 1.14 (0.78–1.8) vs. 2.25 (1.52–2.87); P value <0.001), but a higher count of WBC (9.8 (6.7–13.4) vs. 7.1 (5.4–9.2), P value = 0.004) and neutrophil (8.34 (7.70–8.71) vs. 7.00 (6.20–7.75); P value <0.001) was observed in non-survivors compared to survivors. Also, Non-survivors significantly had a higher concentration of serum creatinine, CRP, and LDH, CPK, CPK-MB, but a lower concentration of Hb than survivors (all P values <0.05).

Table 2.

Laboratory findings on admission of the study population, overall and by survivor status

| Characteristics | Total Median (IQR*) |

Non-survivors Median (IQR*) |

Survivors Median (IQR*) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC count, × 109/L | 7.3 (5.4, 10.5) | 9.8 (6.7–13.4) | 7.1 (5.4–9.2) | 0.004 |

| Lymphocyte count,× 109/L | 2.01 (1.21–2.87) | 1.14 (0.78–1.8) | 2.25 (1.52–2.87) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophil count,× 109/L | 7.29 (6.22–8.23) | 8.34 (7.70–8.71) | 7.00 (6.20–7.75) | <0.001 |

| AST, U/L | 36.0 (26.0–51.0) | 33.5 (20.25–54.0) | 29.0 (18.0–43.0) | 0.087 |

| ALT, U/L | 30.0 (18.0–43.5) | 45.5 (31.0–83.0) | 34.0 (25.0–46.5) | 0.118 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.020 |

| LDH, U/L | 474.0 (356.7–629.4) | 674.0 (487.0–932.0) | 437.0 (350.0–587.0) | 0.002 |

| Hb, g/dL | 12.65 (11.30–14.1) | 12.1 (10.9–13.3) | 12.8 (11.6–14.1) | 0.008 |

| Esr, mm/h | 44.5 (23.75–75.0) | 43.5 (29.5–84.0) | 44.5 (22.0–74.5) | 0.872 |

| CRP, mg/l | 25.0 (7.0–73.0) | 53.8 (21.0–79.0) | 25.0 (5.75–72.0) | 0.015 |

| Cpk, U/L | 88.5 (58.4–151.0) | 115.0 (70.0–222) | 81.7 (58.0–150.0) | 0.016 |

| Cpk-MB, IU/L | 22.0 (15.0–30.0) | 27.4 (19.0–40.3) | 20.0 (14.0–29.0) | 0.019 |

| FBS, mg/dl | 174 (138.0–224) | 192.0 (153.0–262.0) | 166.0 (134.0–216.0) | 0.061 |

*IQR = Inter quartile range

ALT Alanine transaminases, AST Aspartate transaminases, CRP C-reactive protein, CPK Creatine phosphokinase, CK-MB creatine kinase myocardial band, Esr Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, FBS fasting blood sugar Hb Hemoglobin, LDH Lactate dehydrogenase, PT Prothrombin time, WBC White blood cell

Table 3 presents AUC and its 95% confidence interval (CI) of laboratory parameters for predicting COVID-19 death and optimal cutoff points of these parameters. Among assessed parameters, neutrophil count (AUC (95% CI): 0.76 (0.69–0.82)), lymphocyte count (0.75 (0.68–0.81)) and LDH level (0.74 (0.64–0.84)) had the highest diagnostic accuracy for the early detection of COVID-19 death, respectively. Besides, the concentrations of ALT and Esr were non-significant predictors of COVID-19 death.

Table 3.

AUC and Optimal Cut Points of Laboratory test for predicting COVID-19 death in Diabetic patients

| Test | AUC (95% CI) | P value | Optimal cutoff point | Sensitivity % | Specificity % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC count, × 109 /L | 0.66 (0.59–0.73) | <0.001 | 8.1 | 60.0 | 61.7 |

| Lymphocyte count,× 109/L | 0.75 (0.68–0.81) | <0.001 | 1.51 | 72.1 | 70.3 |

| Neutrophil count,× 109/L | 0.76 (0.69–0.82) | <0.001 | 8.0 | 67.2 | 74.3 |

| Hb, g/dL | 0.61 (0.54–0.68) | 0.003 | 12.5 | 64.3 | 57.2 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.60 (0.52–0.69) | 0.010 | 1.36 | 52.0 | 74.6 |

| AST, U/L | 0.64 (0.53–0.74) | 0.010 | 39 | 61.1 | 62.4 |

| ALT, U/L | 0.57 (0.47–0.68) | 0.151 | – | – | – |

| LDH, U/L | 0.74 (0.64–0.84) | <0.001 | 544 | 71.9 | 72.8 |

| Cpk-MB, IU/L | 0.66 (0.55–0.76) | 0.004 | 23 | 67.7 | 60.0 |

| Cpk, U/L | 0.61 (0.51–0.71) | 0.027 | 81.4 | 70.7 | 55.0 |

| CRP, mg/l | 0.61 (0.53–0.68) | 0.012 | 39.0 | 60.4 | 61.0 |

| Esr, mm/h | 0.55 (0.46–0.64) | 0.287 | – | – | – |

| FBS, mg/dl | 0.62 (0.53–0.70) | 0.006 | 179 | 60.0 | 57.0 |

The optimal cutoff point (sensitivity; specificity) of lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, and LDH level to discriminate between survivors and non-survivors was 1.51 × 109/L (72.1, 70.3), 8.0 × 109/L (67.2, 74.3), and 544 U/L (71.9, 72.8), respectively.

The WBC count had significantly lower predictive ability compared to neutrophil and lymphocyte count. (p < 0.001) Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of Hematologic parameters for predicting COVID- 19 death

Table 4 presents predictors for poor outcomes of COVID-19 separately, including death, need to ICU care, and invasive mechanical ventilation in diabetic patients based on the results of logistic regression models.

Table 4.

Predicting factors for death of the COVID-19 in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM): Logistic Regression Analysis

| lass | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristic | Variable | Need to ICU |

Being ventilated during hospitalization N = 65 |

Death N = 79 |

|||

| Crude OR OR(95% CI) | Adjusted§ OR(95% CI) | Crude OR OR(95% CI) | Adjusted§ OR(95% CI) | Crude OR OR(95% CI) | Adjusted§ OR(95% CI) | ||

| Age (≥65/< 65) | 2.34 (1.48–3.72) | 1.72 (1.02–2.94) | 2.40 (1.38–4.17) | 2.40 (1.35–4.28) | 2.44 (1.47–4.05) | 2.0 (1.16–3.44) | |

| Sex (M/F) | 1.24 (0.79–1.95) | – | 1.42 (0.84–2.41) | – | 1.45 (0.85–2.36) | – | |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| HTN | 1.75 (1.10–2.80) | – | 1.15 (0.67–1.96) | – | 1.38 (0.84–2.29) | – | |

| CVD | 1.89 (1.21–2.97) | – | 1.86 (1.09–3.19) | – | 1.49 (0.91–2.42) | – | |

| CKD | 2.30 (1.41–3.77) | – | 2.58 (1.48–4.52) | 2.09 (1.16–3.75) | 2.27 (1.34–3.86) | 2.05 (1.16–3.62) | |

| Other comorbidity* | 2.40 (1.26–4.59) | – | 2.42 (1.18–4.96) | – | 2.08 (1.04–4.16) | 2.20 (1.04–4.63) | |

| Number of co.; Reference category: No comorbidity | |||||||

| 1 | 1.88 (0.94–3.76) | 1.61 (0.72–3.60) | 1.21 (0.52–2.80) | – | 1.14 (0.56–2.33) | – | |

| 2 | 2.61 (1.36–5.0) | 2.23 (1.04–4.78) | 2.42 (1.16–5.06) | – | 1.62 (0.84–3.11) | – | |

| ≥ 3 | 4.80 (2.33–9.88) | 4.08 (1.78–9.34) | 3.46 (1.52–7.83) | – | 2.57 (1.23–5.37) | – | |

| Drug history | |||||||

| ACEIs or ARBs (yes/no) | 1.70 (1.08–2.67) | – | 1.45 (0.86–2.46) | – | 1.41 (0.86–2.32) | – | |

| Statins(yes/no) | 1.76 (1.01–2.76) | – | 1.10 (0.61–1.99) | – | 1.35 (0.78–2.35) | – | |

| Laboratory finding, | Hematological, Biochemistry and Isoenzymes parameters | ||||||

| WBC, ≥ 8.1/< 8.1(× 109 per L) | 2.27 (1.41–3.67) | – | 2.56 (1.46–4.47) | – | 2.36 (1.39–3.99) | – | |

| Lymphocyte, <1.51/ ≥ 1.51 (× 109/L) | 4.33 (2.60–7.19) | 2.28 (1.01–5.15) | 4.67 (2.59–8.47) | – | 5.84 (3.27–10.44) | – | |

| Neutrophil, ≥ 8.0 / < 8.0 (× 109/L)) | 4.55 (2.74–7.57) | 2.32 (1.04–5.24) | 5.02 (2.82–8.93) | 5.00 (2.82–8.94) | 6.65 (3.75–11.80) | 6.62 (3.73–11.75) | |

| Hb, <12.5/ > 12.5(g/dl) | 2.38 (1.45–3.88) | 2.03 (1.20–3.43) | 1.87 (1.04–3.15) | – | 2.21 (1.30–3.77) | 2.05 (1.13–3.72) | |

| AST, ≥ 39 / < 39 (U/L) | 2.32 (1.46–5.46) | 2.39 (1.12–5.13) | 2.65 (1.26–5.61) | 2.40 (1.25–5.69) | 2.62 (1.26–5.44) | – | |

| Creatinine, ≥1.36/<1.36 (mg/dl) | 2.57 (1.55–4.24) | 2.67 (1.25–5.58) | 2.63 (1.49–4.66) | 2.64 (1.12–6.21) | 3.18 (1.83–5.53) | 3.10 (1.38–6.98) | |

| CRP, ≥39/<39 (mg/dl) | 1.65 (0.96–2.81) ‡ | – | 1.30 (0.70–2.40) | – | 2.22 (1.25–3.94) | – | |

| FBS, ≥179/<179 (mg/dl) | 1.72 (1.03–2.88) | – | 1.63 (0.89–2.95) | – | 1.72 (0.97–3.05) | – | |

| LDH, ≥544/<544(U/L) | 4.0(1.95–8.17) | 4.31 (1.36–13.68) | 3.74 (1.64–8.49) | 3.45 (1.36–9.27) | 7.04 (3.05–16.26) | 6.53 (2.51–16.97) | |

| Cpk, ≥81.4/<81.4(U/L) | 2.54 (1.25–5.18) | 3.67 (0.96–14.23) | 2.78 (1.23–6.27) | – | 2.44 (1.17–5.09) | – | |

| Cpk-MB, ≥23/<23(IU/L) | 3.09 (1.45–6.56) | – | 2.69 (1.12–6.06) | – | 3.18 (1.47–6.89) | – | |

†P- value <0.05 ‡ P- value <0.20; § in each class, all variables with p < 0.2 in the univariaite model were included in multivariate model

OR Odds Ratio, CI Confidence Interval;

ACEIs angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARBs angiotensin II receptor blockers, CKD Chronic Kidney diseases, CVD Cardiovascular diseases, HTN Hypertension, ICU Intensive care unit

ALT Alanine transaminases, AST Aspartate transaminases, CRP C-reactive protein, CPK Creatine phosphokinase, CK-MB creatine kinase myocardial band, Esr Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, FBS fasting blood sugar, Hb Hemoglobin, LDH Lactate dehydrogenase, PT Prothrombin time, WBC White blood cell

In the multivariate model, significant predictors of “death of COVID-19” were age 65 years or older (OR (95% CI): 2.0 (1.16–3.44), comorbidity CKD (2.05 (1.16–3.62), presence of other comorbidity (2.20 (1.04–4.63)), neutrophil count ≥8.0 × 109/L)6.62 (3.73–11.7 ((, Hb level < 12.5 g/dl (2.05 (1.13–3.72) (, and creatinine level ≥ 1.36 mg/dl (3.10 (1.38–6.98)). (All p –values <0.05).

Patients with age ≥ 65 years, 2 or more comorbidities, lymphocyte count <1.51 × 109/L, neutrophil count ≥8.0 × 109/L, Hb level < 12.5 g/dl, AST level ≥ 39 U/L, creatinine level ≥ 1.36 mg/dl, LDH level ≥ 544 U/L, and Cpk level ≥ 81.4 U/L had significantly higher odds for requiring ICU care than others. (All p –values <0.05).

Also, patients with age 65 years or older, comorbidity CKD, neutrophil count ≥8.0 × 109/L, AST level ≥ 39 U/L, creatinine level ≥ 1.36 mg/dl, LDH level ≥ 544 U/L were more likely to require invasive mechanical ventilation than others. (All p –values <0.05).

Based on log-rank test results, the difference in the survival distributions between two age groups ≥65 years and < 65 years were statistically significant (χ2(1) = 8.73, p = 0.003); but, the differences between males and females did not reach statistical significance (χ2(1) = 2.88, p = 0.09) (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Survival Curve in Diabetic Patients with COVID-19 by gender status (Kaplan Meier & log rank test)

Fig. 3.

Survival Curve in Diabetic Patients with COVID-19 by Age – group (Kaplan Meier& log rank test)

Discussion

In this retrospective observational study, we compared the characteristics of hospitalized diabetic patients with COVID-19 between survivors and non-survivors and investigated the predicting factors for poor outcomes including need to ICU care and invasive mechanical ventilation and in-hospital death.

Based on our results, age 65 years or older, neutrophil count ≥8.0 × 109/L, and creatinine level ≥ 1.36 mg/dl were significant predictors for all poor outcomes of COVID-19 including need to ICU care, invasive mechanical ventilation, and death in diabetic patients. Among predictors of COVID-19 death, Hb level < 12.5 g/dl and the presence of comorbidity CKD were also associated with need to ICU care and invasive mechanical ventilation, respectively. However, AST level ≥ 39 U/L, LDH level ≥ 544 U/L, Cpk level ≥ 81.4 U/L, lymphocyte count <1.51 × 109/L, were associated with need to ICU care and / or invasive mechanical ventilation but not with COVID-19 death.

Shi et al. also observed infected patients with diabetes who died were older, were more likely to have hypertension and CVD and presented more dyspnea compared with survivors although frequency of CKD was probable between groups [11]. It should be noted that there were no significant difference in frequency of hypertension and CVD as well as percentage of ACEIs/ARBs and statins consumption between survivors and non-survivors in our study. Contrary to the recent hypothesis which related severity of COVID-19 infection to elevated expression of ACE2 in those treated with ACEI/ARB drugs [12–14], we did not observe any significant differences in use of these drugs between survivor and non-survivor groups.

According to the laboratory findings, non-survivors had lower lymphocyte count and higher counts of WBC and neutrophil besides higher concentration of serum creatinine, CRP, LDH, CPK and CPK-MB, but lower concentration of Hb compared to survivors, reflecting severe inflammatory response and cardiac and renal impairments in non-survivors. Our findings were in agreement with previous observations in COVID-19 patients [11, 15–17]. These biochemical abnormalities point to that covid-19 infection may be lead to progressive systemic injuries and consequently death in diabetic patients. The mechanisms linking diabetes with high risk of mortality were pulmonary dysfunction and deleterious inflammation which has been indicated in results of comparison between survivors and non-survivors [15, 18]. Chen et al. indicated CRP as the only risk factor for mortality in diabetic patients with COVID-19 as a clinical manifestation of systemic inflammation [19]. This imbalance between pro-inflammation and anti-inflammation process could partly explained the reported association between diabetes and low pulmonary function [20].

Regard to baseline FBS, concentration of blood glucose was higher in non-survivors in comparison with survivors, although it is not statistically significant, it has clinically importance. Zhu et al. retrospectively studied nearly 1000 COVID-19 patients with diabetes in China; they showed that fatality rate in patients with well-controlled blood glucose (1.1%) was lower compared to patients with poorly-controlled blood glucose (11%). Patients with good glycemic control had lower incidence of ARDS, multi-organ injuries and septic shock relative to the patients with poor glycemic control [21]. Glycemic variability was indicated as a probable predictor for severe complications and mortality in COVID-19 infected patients with diabetes. It has been reported that hyperglycemia may reduce the defensive capacity of respiratory tract through increasing glucose level in airway epithelial secretions [22] as well as increase risk of mortality in infected patients via overproduction of advanced glycation end products and dysfunction of immunoglobulins [23]. Moreover, Covid-19 which was reported to bind ACE2 receptor, may damage pancreatic function and lead to worse glycemic status via binding to this receptor in pancreas [15, 24].

Previous studies have been indicated diabetes as a risk factor for poor outcomes and high fatality in COVID-19 patients [8, 25, 26]; however no study focused on biochemical indicators as predicting factors for death in diabetic infected patients, presenting the optimal cutoff points to discriminate between survivors and non-survivors. Among laboratory parameters for predicting death, neutrophil and lymphocyte count as indicators for immune function and LDH level as a marker of tissue breakdown had the highest diagnostic accuracy in infected diabetic patients.

According to the results of logistic regression models, older age, CKD, high neutrophil count and creatinine level were significant predictors of death, requiring ICU care and invasive mechanical ventilation. Moreover, low lymphocyte count and high LDH and Cpk level were associated with higher odds of ICU care. Our observations were in line with previous findings as Shi et al. declared advanced age as an independent risk factor for in-hospital death among COVID-19 patients with diabetes [11]. Totally, old age was demonstrated as an independent predictor of death in COVID-19 patients due to age-dependent decrease in immune function as we observed more lymphopenia in critically ill patients too [27, 28]. Concordant with previous studies, lymphopenia has been shown as a key characteristic of COVID-19 infection, specifically in critically ill and deceased patients [16, 29]. Furthermore, it should be noted that diabetes has additive destructive effects on innate and adaptive immunity [30]. Moreover, our results showed that underlying comorbidities like CKD could be associated with poor outcomes in patients with diabetes. Therefore, diabetic patients with underlying renal failure should attract more attention.

The present study is among the first studies with the approach of exploring the predictors of poor prognosis and mortality in COVID-19 patients with diabetes. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, it has some limitations. First, we could not retrieve the pre-hospital status of diabetic patients including their glycemic control which could be significantly associated with numerous clinical risk factors for the poor outcomes. Therefore, the confounding effects of these factors cannot be excluded. Also, given this lack of pre-hospital data, it was not possible for us to access the trend of blood glucose change. Second, participants of this study were relatively severe cases which needed hospitalization. Therefore, the rate of mortality was higher to some extent and might influence the interpretation of the results. Third, we did not consider the drugs which have been used for COVID-19 treatment during hospitalization in analysis. So we cannot rule out its confounding effects. Moreover, we missed the data about antidiabetic treatments of patients which might lead to bias in analysis and interpretation, as indicated by Chen et al. that insulin users had poor prognosis of COVID-19 [19]. Furthermore, there is also discussion on harmful effects of some oral hypoglycemic agents such as Sodium-Glucose-Transporter-2 inhibitors versus beneficial effects of metformin on COVID-19 infected individuals with diabetes [31, 32]. Therefore, further studies investigating impact of different glucose-lowering medications on infected diabetic patients are warranted.

We demonstrate a guide identifying predicting factors and their cutoff points for poor outcomes including need to ICU care and invasive mechanical ventilation and in-hospital death in admitted COVID-19 patients with diabetes. These risk factors could be considered by clinicians to pay special attention to high-risk patients.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all persons that help us in data gathering.

Abbreviations

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- ACEIs

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARBs

Angiotensin II receptor blockers

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- AST

Aspartate transaminase

- ALT

Alanine transaminases

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- ESR

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- Cpk

Creatine phosphokinase

- Cp-MB

Creatine kinase myocardial band

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- SD

Standard deviation

- IQR

Interquartile range

- ROC

Receiver operating curve

- AUC

Under the curve

- Cis

Confidence interval

- HTN

Hypertension

- PT

Prothrombin time

- WBC

White blood cell

- ACEIs

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARBs

Angiotensin II receptor blockers

Authors’ contributions

HR, H-SE and MQ had the idea for and designed the study and had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. HR, H-SE, AS and ESh drafted the paper. AZ, MN, SH-DM, FO, ShS, Zkh, and NShH collected the MM, and MQ did the analysis, and all authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and gave final approval for the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

Alborz University of Medical Sciences.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Research and Ethics Committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences (ABZUMS) approved the present research and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.worldometer. COVID-19 CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC. 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?utm_campaign=homeAdvegas1?%20.

- 2.Monto AS. Epidemiology of influenza. Vaccine. 2008;26:D45–DD8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent J-L, Taccone FS. Understanding pathways to death in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:430–432. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30165-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Huang Y, Lu Z, Li R, Wang B. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19: evidence from meta-analysis. Aging. 2020;12(7):6049–6057. doi: 10.18632/aging.103000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y, Diao B, Lv X, Zhu J, Liang W, Liu L et al. 2019 novel coronavirus disease in hemodialysis (HD) patients: report from one HD center in Wuhan, China. medRxiv. 2020:2020.02.24.20027201. 10.1101/2020.02.24.20027201.

- 7.Edagawa S, Kobayashi F, Kodama F, Takada M, Itagaki Y, Kodate A, Bando K, Sakurai K, Endo A, Sageshima H, Nagasaka A. Epidemiological features after emergency declaration in Hokkaido and report of 15 cases of COVID-19 including 3 cases requiring mechanical ventilation. Global Health & Medicine. 2020;2:112–117. doi: 10.35772/ghm.2020.01024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo W, Li M, Dong Y, Zhou H, Zhang Z, Tian C, et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Roncon L, Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Zuliani G. Diabetic patients with COVID-19 infection are at higher risk of ICU admission and poor short-term outcome. J Clin Virol. 2020;104354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, Zhao J, Liu H, Peng J, Li Q, Jiang C, Zhou Y, Liu S, Ye C, Zhang P, Xing Y, Guo H, Tang W. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e16–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Q, Zhang X, Jiang F, Zhang X, Hu N, Bimu C, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Mortality of COVID-19 Patients With Diabetes in Wuhan, China: A Two-Center, Retrospective Study. Diabetes Care. 2020:dc200598. 10.2337/dc20-0598. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):e21. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li XC, Zhang J, Zhuo JL. The vasoprotective axes of the renin-angiotensin system: Physiological relevance and therapeutic implications in cardiovascular, hypertensive and kidney diseases. Pharmacological Research. 2017;125(Pt A):21–38. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94(7):e00127–e00120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Y, Yang Y, Wang F, Ren H, Zhang S, Shi X, Yu X, Dong K. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with severe covid-19 with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care. 2020;8(1):e001343. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Liu H, Wu Y, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein OL, Aviles-Santa L, Cai J, Collard HR, Kanaya AM, Kaplan RC, Kinney GL, Mendes E, Smith L, Talavera G, Wu D, Daviglus M. Hispanics/Latinos with type 2 diabetes have functional and symptomatic pulmonary impairment mirroring kidney microangiopathy: findings from the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):2051–2057. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Yang D, Cheng B, Chen J, Peng A, Yang C, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with diabetes and COVID-19 in association with glucose-lowering medication. Diabetes Care. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Giovannelli J, Trouiller P, Hulo S, Chérot-Kornobis N, Ciuchete A, Edmé J-L, Matran R, Amouyel P, Meirhaeghe A, Dauchet L. Low-grade systemic inflammation: a partial mediator of the relationship between diabetes and lung function. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu L, She Z-G, Cheng X, Qin J-J, Zhang X-J, Cai J, Lei F, Wang H, Xie J, Wang W, Li H, Zhang P, Song X, Chen X, Xiang M, Zhang C, Bai L, Xiang D, Chen MM, Liu Y, Yan Y, Liu M, Mao W, Zou J, Liu L, Chen G, Luo P, Xiao B, Zhang C, Zhang Z, Lu Z, Wang J, Lu H, Xia X, Wang D, Liao X, Peng G, Ye P, Yang J, Yuan Y, Huang X, Guo J, Zhang BH, Li H. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020;31:1068–1077.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philips BJ, Meguer J-X, Redman J, Baker EH. Factors determining the appearance of glucose in upper and lower respiratory tract secretions. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(12):2204–2210. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1961-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold JN, Wormald MR, Sim RB, Rudd PM, Dwek RA. The impact of glycosylation on the biological function and structure of human immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:21–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, Bi Y, Ma X, Zhan F, Wang L, Hu T, Zhou H, Hu Z, Zhou W, Zhao L, Chen J, Meng Y, Wang J, Lin Y, Yuan J, Xie Z, Ma J, Liu WJ, Wang D, Xu W, Holmes EC, Gao GF, Wu G, Chen W, Shi W, Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang I, Lim MA, Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia–a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Chen Y, Gong X, Wang L, Guo J. Effects of hypertension, diabetes and coronary heart disease on COVID-19 diseases severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020.

- 27.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Opal SM, Girard TD, Ely EW. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis in elderly patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;41(Supplement_7):S504–SS12. doi: 10.1086/432007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Muller L, Gorter K, Hak E, Goudzwaard W, Schellevis F, Hoepelman A, et al. Increased risk of common infections in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(3):281–288. doi: 10.1086/431587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma S, Ray A, Sadasivam B. Metformin in COVID-19: a possible role beyond diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;164:108183. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pal R, Bhadada SK. Should anti-diabetic medications be reconsidered amid COVID-19 pandemic? Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2020;163:108146. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.