COVID-19 pandemic has emerged as a major public health issue for the mankind and every human being has been affected by the pandemic in one or the other way (Tandon, 2020a, 2020b). COVID-19 has been considered to be a mental health crisis, not only for those infected with the same, but also for the health care workers (Grover et al., 2020a). Throughout the world makeshift COVID ward have been created to provide care to people infected with the COVID-19 virus. Further, doctors from the different specialties have been pooled together to provide care to persons infected with the virus. Although everyone, who is infected with the virus does not develop the severe symptoms of the infection and do not require the life support measures, but most patients encounter the mental health issues while in the COVID ward and after recovery from the same (Sahoo et al., 2020b,a). Due to this it is suggested that everyone infected with the COVID-19, should be provided with mental health support (Grover et al., 2020a). Considering the importance of mental health consequences, at many places, mental health professionals (MHPs) have been posted in the COVID ward to cater to the mental health needs of the persons with COVID-19 infections. At some places, these services are being provided in-person, with MHPs assessing the patients with the COVID-19 infection in the COVID ward and at other places these services are being catered through the telephone or video-conferencing (Grover et al., 2020b; Sahoo et al., 2020b,c). However, it is humanly not possible for the MHPS to assess all the patients in the COVID ward for the mental health issues. This is not a cost effective model as this requires MHPs to be present round the clock, in the personal protective equipments (PPEs). The use of PPEs takes away the advantage of face-to-face interaction, and resultantly a therapeutic alliance is not established properly (Padhy et al., 2020; Sagar et al., 2020). Further, this model requires large manpower of the MHPs to meet the requirement and also exposes them to the risk of infection. Further, if the MHPs are posted for only few hours, this restricts the availability of mental health services to few hours of the day, as MHPs are not posted during all the shifts. On the other hand, while providing services telephonically or through videoconferencing it is often not possible to reach to all the patients, especially those who are admitted in the ICUs and are suffering from delirium. Hence, both the models have their limitations and there is a need to evolve a model, which can improve the mental health care for patients with COVID-19 patients, without exposing all the MHPs to the risk of COVID-19 infection, while providing the services.

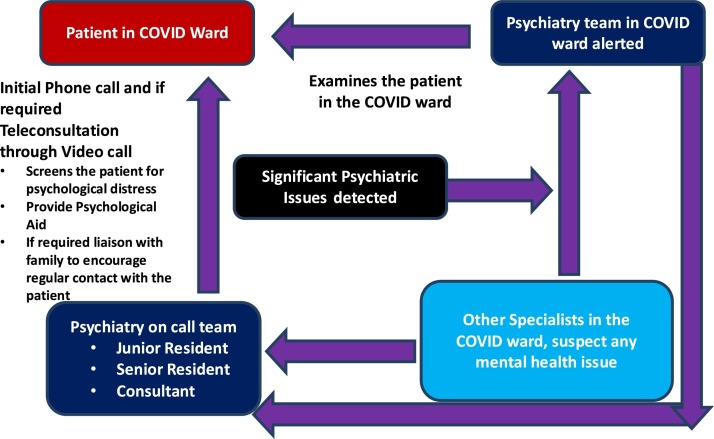

Keeping this in mind, we evolved a model (Fig. 1 ), which involved the modification of usual consultation-liaison (CL) Psychiatry model of providing care to patients in other inpatient setting. In the usual model whenever a call is received by the CL Psychiatry team, the junior resident/trainee resident first examines the patient under the supervision of a senior resident/registrar. Then the case is reviewed by the consultant incharge and final plan of management is decided and executed (Grover et al., 2017). Additionally, for providing CL services to the emergency, one of the junior Resident/trainee resident is stationed in the emergency and any patient who requires mental health care is attended. This has led to overall increase in the psychiatry referrals in the emergency set-up (Grover et al., 2015).

Fig. 1.

Emerging Consultation-Liaison Model for providing care to patients with COVID infection.

During the COVID times, the CL Psychiatry model was modified to provide round the clock services to the patients with COVID-19. In this model, psychiatry residents are involved at 2 levels- one involved some of them being posted in the COVID ward and some are involved in providing services telephonically and/or through videoconferencing (Fig. 1). Both the set of residents are supervised by the same team of senior resident/registrar and the faculty members. The junior resident/trainee posted at providing services telephonically and/or through videoconferencing, makes the telephone calls to the patients (who have access to a personal phone in the COVID ward) in the COVID ward within 24−48 hours of their admission, carries out a brief assessment and screens them for psychological distress and any diagnosable psychiatric disorders. He/she also provides psychological support in the form of reassurance and hope for recovery. Patients experiencing anxiety and sleep disturbances are managed with melatonin or benzodiazepines on SOS basis, depending on the respiratory status (SpO2). Patients found have severe mental illnesses are monitored more closely for the need for use of psychotropic medications, ongoing symptoms including suicidality, medication compliance and possible drug interactions. Those patients who are considered to have higher level of psychological distress are managed with video-conferencing. Patients are also informed that they can store the phone number of the mental health team and can initiate the call on their own, in case they feel the need for further psychological support. Patients with significant psychological issues are followed up till they are discharged from the COVID ward. Patients considered to have more severe ailment or at risk of self-harm are intimated to the mental health team posted in the COVID-19, which examines the patients personally and carries out the required intervention. On the other hand, the psychiatry resident posted in the COVID ward or resident/ consultant of any other specialty can initiate a psychiatry consultation telephonically/ videoconferencing with the consultant to discuss the case, show the patient to the consultant through video-conferencing and seek advice. This model works well for patients who have delirium, are uncooperative for any kind of assessment or intervention for their physical ailment, are experiencing substance withdrawal in the intensive care set-up, and are experiencing catatonia. The resident/consultant of any specialty has the liberty to contact either of the psychiatry teams (that is posted in the COVID ward or the team available for Teleconsultation) for the consultation.

Usually, one or two psychiatry residents are posted in the COVID ward at shifts of 6 h, who not only provide mental health care but are also involved in taking care of physical health issues of the COVID-19 patients. On the other hand, 2–3 residents are posted for providing the telephonic/videoconferencing services, along with 3 psychiatry consultants available round the clock. These teams also address to the psychological issues among the health care workers. Further, the same team tries to follow-up the patients with significant psychological issues after discharge from the COVID ward. This model draws some or other principles from other CL Psychiatry models (Grover, 2011) and helps in not only providing patient care, but also involves teaching the psychiatry residents and specialists from other departments, providing supervision and resolving crisis. This model also incorporates the telepsychiatry.

We found this model to involve fewer mental health professionals with proper coverage of the mental health services. There is a need to use this model at a wider scale, to improve the mental health care of the patients with COVID-19.

Financial disclosure

We have no financial disclosure to make.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Grover S. State of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry in India: current status and vision for future. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2011;53:202–213. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.86805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S., Sarkar S., Avasthi A., Malhotra S., Bhalla A., Varma S.K. Consultation-liaison psychiatry services: difference in the patient profile while following different service models in the medical emergency. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2015;57(361) doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.171854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S., Sahoo S., Aggarwal S., Dhiman S., Chakrabarti S., Avasthi A. Reasons for referral and diagnostic concordance between physicians/surgeons and the consultation-liaison psychiatry team: an exploratory study from a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2017;59:170–175. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_305_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S., Dua D., Sahoo S., Mehra A., Nehra R., Chakrabarti S. Why all COVID-19 hospitals should have mental health professionals: the importance of mental health in a worldwide crisis! Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S., Mehra A., Sahoo S., Avasthi A., Tripathi A., D’Souza A., Saha G., Jagadhisha A., Gowda M., Vaishnav M., Singh O., Dalal P.K., Kumar P. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on the state of mental health services in private sector in India. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2020;62:363. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_567_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padhy S.K., Rina K., Sarkar S. Smile, grimace or grin? Recalibrating psychiatrist-patient interaction in the era of face masks. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar R., Chawla N., Sen M.S. Preserving the “human touch” in times of COVID-19. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;54 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S., Mehra A., Dua D., Suri V., Malhotra P., Yaddanapudi L.N., Puri G.D., Grover S. Psychological experience of patients admitted with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;54 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S., Mehra A., Suri V., Malhotra P., Yaddanapudi L.N., Dutt Puri G., Grover S. Lived experiences of the corona survivors (patients admitted in COVID wards): a narrative real-life documented summaries of internalized guilt, shame, stigma, anger. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S., Mehra A., Suri V., Malhotra P., Yaddanapudi N., Puri G.D., Grover S. Handling children in COVID wards: a narrative experience and suggestions for providing psychological support. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R. COVID-19 and human mental health preserving humanity: maintaining sanity, and promoting health. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R. The COVID-19 pandemic, personal reflections on editorial responsibility. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;50 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]