Abstract

During development the vast majority of cells that will later compose the mature cerebral cortex undergo extensive migration to reach their final position. In addition to intrinsically distinct migratory behaviors, cells encounter and respond to vastly different microenvironments. These range from axonal tracts to cell-dense matrices, electrically active regions and extracellular matrix components, which may all change overtime. Furthermore, migrating neurons themselves not only adapt to their microenvironment but also modify the local niche through cell-cell contacts, secreted factors and ions. In the radial dimension, the developing cortex is roughly divided into dense progenitor and cortical plate territories, and a less crowded intermediate zone. The cortical plate is bordered by the subplate and the marginal zone, which are populated by neurons with high electrical activity and characterized by sophisticated neuritic ramifications. Neuronal migration is influenced by these boundaries resulting in dramatic changes in migratory behaviors as well as morphology and electrical activity. Modifications in the levels of any of these parameters can lead to alterations and even arrest of migration. Recent work indicates that morphology and electrical activity of migrating neuron are interconnected and the aim of this review is to explore the extent of this connection. We will discuss on one hand how the response of migrating neurons is altered upon modification of their intrinsic electrical properties and whether, on the other hand, the electrical properties of the cellular environment can modify the morphology and electrical activity of migrating cortical neurons.

Keywords: cerebral cortex, development, electric field, neuronal migration, dendritogenesis

Introduction

Construction of the nervous system is achieved through a complex succession of developmental processes. Among them, two are known to predominantly occur at different developmental stages in the cerebral cortex, cell migration largely embryonically and synaptogenesis postnatally.

Research on chemical cues and adhesion molecules guiding neuronal migration, shaping tissue architecture and synapse formation has shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying migration as well as morphogenesis of dendrites and spines and have been extensively reviewed (Solecki, 2012; Arai and Pierani, 2014; Barber and Pierani, 2016; Ledda and Paratcha, 2017; Chighizola et al., 2019; Lanoue and Cooper, 2019). Besides molecular mechanisms, electric field (EF) is another factor which has been shown to define the morphology and specification of whole tissues and can in certain cases outplay chemical guidance (McCaig et al., 2009; Levin et al., 2017). The field of cortical development is starting to recognize the importance of ion flow for regulation of early neuronal development: proliferation, migration and differentiation. While nowadays EF is an emerging player in guiding orientation and speed of migrating neurons and in regulating neuronal morphology, it remains to be determined whether and how neuronal migration and morphology establishment are linked.

EFs naturally occur in tissues as a consequence of polarized ion transport inside and outside the cells. Numerous examples of cellular and tissue behavior controlled by bioelectric states are described in amphibians and worms, where altered morphogenesis of whole organs and body parts can occur under ectopic electric stimuli, as well as in mammals during the processes of wound healing, cell proliferation and nerve growth stimulation. Many neural cell types manifest electrotactic behaviors, including neural crest cells and hippocampal neurons (McCaig et al., 2005; Yao et al., 2008; Iwasa et al., 2017). Human neural stem cells migration is also directed by EF while blockade of receptors to classical chemotactic cues does not affect electrotactic responses (Feng et al., 2012, 2017). These results raise the intriguing possibility that cell migration in the developing brain occurs through tissues with steady electrical signals (McCaig et al., 2009; Iwasa et al., 2017) and is guided by them (Li et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2017).

In general, the effects of applied EF on neuronal cells are similar and include changes in length and orientation of cell bodies and leading processes, neurite branching and stimulation of directed migration (Yao and Li, 2016; Bertucci et al., 2019). Indeed, electric stimulation seems to drive all kinds of polarized responses. In vitro applications of electric currents to cultured hippocampal cells initiate the cascade of morphological and molecular events. The division cleavage plane turns orthogonally and the mitotic spindle parallel to the EF vector. The Golgi apparatus and centrosome, MAP2+ (dendrite-specific) microtubules and eventually the leading process turns to the cathode and cells migrate in a directed fashion with a leading process at the front (Yao et al., 2009). Examples of EF-induced changes specifically in cortical neurons have been reported: cortical axon length and orientation are a subject to specific electric regulation (Tang-Schomer, 2018). Furthermore, electric stimulation of postnatal prefrontal cortical neurons in culture improves dendritic branching and length as well as synaptic protein amounts in both WT and genetically modified conditions (NRG1-knock-out and DISC1-locus impaired mice), associated with psychiatric disorders (Zhang et al., 2017). This provides, on the one hand, a proof for direct electric regulation of cortical dendrito- and synaptogenesis, and on the other hand, an example of electric cue overriding genetic state.

In adult neural tissue, electrical communication is granted through chemical synapses via neurotransmitters, which regulate ion flow through ionotropic receptors. Synaptic connections are canonically at the origin of presynaptic Ca2+ influx in response to action potential membrane depolarization and post-synaptic in response to neurotransmitter receptors activation. The same machinery is utilized during post-mitotic neuronal migration and maturation: voltage- and neurotransmitter-gated ion channels are capable of regulating the resting membrane potential, which is usually low in immature neurons (Levin et al., 2017). Neurotransmitters are present throughout developing neural tissues, can be released by cells in close vicinity, i.e., neuroblasts or maturing neurons, and can act on migrating neurons in paracrine, non-synaptic, fashion (Spitzer, 2006; Luhmann et al., 2015; Ojeda and Ávila, 2019). Gap junctions, or electric synapses, undoubtedly also play roles during development, especially in electrically active zones, such as the subplate (SP) (Luhmann et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2019).

Here, we aim to analyze EF-guided migration and maturation in the developing cerebral cortex, with a major focus on radially migrating glutamatergic neurons. We use the term EF to designate a sum of electric currents in the tissue and extracellular environment in general as well as electric activity and responses locally, inside the cell.

Dendritogenesis normally occurs after neurons have completed their migration and is, thus, a post-migratory step of neuronal maturation. In the cortical tissue dendritic development is shaped by extrinsic regulation in destined cortical layers (Martineau et al., 2018). Yet, upon electric activity amplification in migrating cortical neurons, precocious and ectopic dendritogenesis is observed (Bando et al., 2016; Hurni et al., 2017). Here we will review the mechanisms mediating the EF-dependent control of neuronal migration and maturation and we will also touch upon how these two processes can be related to synaptic organizing molecules prior to synaptic formation.

Ca2+ Is an Intracellular Proxy of Extrinsic Ef Fluctuations in Developing Neurons

EF-triggered receptors displayed on the cell surface activate a number of signaling pathways, such as ERK, PI3K and small Rho GTPases (Yao and Li, 2016). However, the central regulator of neuronal EF-guided processes, both migration and dendritogenesis, is attributed to downstream intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, which convert electrical signaling to physiological responses and are used as a readout of electrical activity (Uhlen et al., 2015; Horigane et al., 2019).

In addition to intracellular Ca2+ release in migrating neurons, Ca2+ enters from the extracellular environment and is mediated by VGCC type Ca2+ channels. These channels are sensitive to membrane depolarization and are typically reactive to synapse-triggered action potentials. In young neurons devoid of synapses, these channels are hypothetically capable of responding to low voltage changes (Horigane et al., 2019). The latter can be produced by neurotransmitter- and voltage-gated ion channels, which are well expressed in the developing cortex and are extensively documented as controlling migration and neuritogenesis in cell-autonomous and non-autonomous ways. Clinical importance of ion channels in early brain development is recognized and indicates their role in transmembrane voltage regulation and/or in migration before stable synapse formation (Smith and Walsh, 2020).

Dendritogenesis in general is very sensitive to extrinsic cues and the molecular mechanisms are well studied and summarized in several excellent reviews (Arikkath, 2012; Valnegri et al., 2015; Ledda and Paratcha, 2017; Lanoue and Cooper, 2019). In cortical neurons, extracellular Ca2+ influx is important for dendritic branching, while intracellular Ca2+ release affects dendritic branching, axonal growth and density of filopodia (Ramakers et al., 2001). Ca2+ events in cortical neurons are localized and may organize dendritic and spine morphology from within: Ca2+ waves initiate at dendritic branch points and propagate predominantly at primary apical dendrites. Earlier in development Ca2+ events in dendrites are characterized by bigger amplitudes and seem to be dependent mostly by changes of membrane voltage and L type VGCC Ca2+ channels (Ross, 2012). Overall, Ca2+ signaling in dendritogenesis is well recognized (Konur and Ghosh, 2005).

Intracellular Ca2+ fluctuations could thus constitute a convergence point for chemical cues-signaling pathways and EF, summing up in local Ca2+ changes that in turn regulate migration, dendritogenesis, and spine formation.

Cerebral Cortex and Electrically Active Zones

Direct Studies of EF in the Cortex

In the cerebral cortex, first measurements of tissue endogenous electric current flow were performed in 2013 (Cao et al., 2013) in the walls of the lateral ventricle along the rostral migratory pathway in adult mice. An electric potential gradient measured in the interstitial space along the pathway is of 3–5 mV/mm. It is formed by positively charged ions in the extracellular space, which in turn is supported by currents through cells and tissues. These currents depend on polarized expression of electrogenic pumps (e.g., Na+/K+ -ATPases), which are effectively suppressed by selective inhibitors with the subsequent reduction of electric currents in the tissue. Neuroblasts migrating along the pathway rise their migration speed or change direction upon application to the brain slice of higher EF or reversal of the field polarity (Cao et al., 2013). Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of EF effectively suppresses migration in 3D cultures of subventricular zone (SVZ) explants, while EF stimulation, in addition to promoting migration, induces expression of adhesive molecules thus increasing cell-cell contacts (Cao et al., 2014).

Evidence for EF-guidance in cortical tissue in vivo are coming from the brain injury field. Increased cell proliferation in the SVZ and directed migration toward the source of the current is observed during motor cortex electrical stimulation (Jahanshahi et al., 2013). Human neural stem cells transplants into the rat rostral migratory stream are efficiently guided by endogenous EF, while applied electric stimulation redirects migration of subpopulation of cells regardless of endogenous tissue cues (Feng et al., 2017).

Electrical Activity During Cortical Development

There are no studies on applied or otherwise manipulated direct EF specifically for the developing cortex and migrating neurons in early stages. Nevertheless, electrical activity of migrating cells in the embryonic cortex is well documented. Individual neurons display spontaneous Ca2+ activity (Corlew et al., 2004; Egorov and Draguhn, 2013; Bando et al., 2016; Yuryev et al., 2018; Mayer et al., 2019) and inward Na+/outward K+ currents (Picken Bahrey and Moody, 2003). Ca2+ waves through the mouse cortical plate are recorded in utero (Yuryev et al., 2016). Recordings in the human developing subplate show spontaneous oscillatory activity of GABAergic origin, but almost no synaptic connections (Moore et al., 2011).

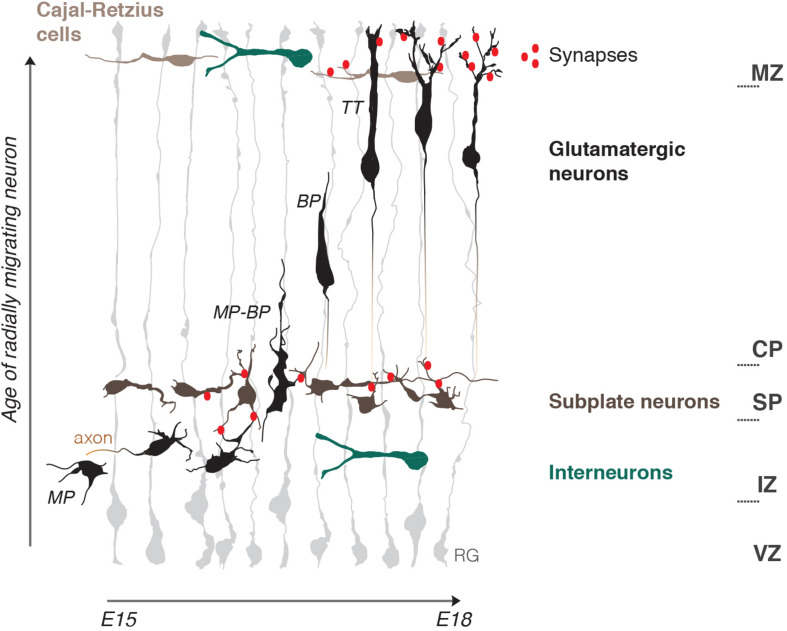

The developing cerebral cortex is a rapidly expanding layered structure that mostly relies on highly organized radial migration of newly born glutamatergic neurons. During radial migration neurons undergo morphological changes which are accompanied by the change of migration mode and are influenced by tissue environments (Ohtaka-Maruyama and Okado, 2015; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the embryonic mouse cortex and its electrical zones. Two electrically active borders, the subplate (SP) and the marginal zone (MZ), organize neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex. The MZ and SP coincide with morphology and migration mode transformations of radially migrating neurons and represent pathways for tangentially migrating neuronal populations: Cajal-Retzius cells and Interneurons. Note the presence of early functional synaptic contacts in the SP and MZ. Axonogenesis and polarization of migrating neurons occur under the SP and dendritogenesis in the MZ. Neuritogenesis is thus enhanced within the two zones. Radial migration is depicted starting from bipolar neurons (BP) in the intermediate zone (IZ) onwards that represent steps mostly studied in terms of electrical activity. RG, radial glia; MP, multipolar neuron; BP, bipolar neuron; MP-BP, transitional morphology of the neuron going through the SP; TT, neuron undergoing terminal translocation; VZ, ventricular progenitors zone; IZ, intermediate zone; CP, cortical plate.

Just born multipolar neurons slowly migrate toward the pial surface through the intermediate zone (IZ) by a multipolar migration mode, with long pauses and frequently changing directionality (Tabata and Nakajima, 2003). This continues until they reach the first structural «border», the SP. The SP is a layer of transient electrophysiologically active and morphologically mature neurons which manifest a high electrical activity as they establish afferent and efferent synaptic connections within the developing cortex (Luhmann et al., 2018). Here multipolar neurons start their polarization process by the formation of tangentially oriented axonal outgrowth (Hatanaka and Yamauchi, 2013). This is well-studied from a biochemical point of view. Reelin, a powerful chemical regulator of radial migration, is present in the IZ and, by initiation of a RAP1-dependent N-cadherin cell surface rise, allows multipolar neurons to sense microenvironmental cues, which in turn can induce polarization (Hansen et al., 2017). Axonal induction is also promoted by GABAB receptor, and GABA is believed to be present in the IZ due to tangentially migrating interneurons (Bony et al., 2013) (also see GABA chapter). Moreover, SP neurons make glutamatergic synaptic contacts with multipolar migrating neurons. This induces NMDAR-dependent Ca2+ entry into the migrating neuron and, as a result, facilitates the morphology and migration mode switch to bipolar neurons (Ohtaka-Maruyama et al., 2018; Ohtaka-Maruyama, 2020). Bipolar neurons then migrate by locomotion along radial glia fibers. It is possible that electric stimulation from radial glia is adding to the multipolar-bipolar transition, as Ca2+ bursts in both cell types are synchronized during this process (Rash et al., 2016).

Bipolar locomotion is a fast mode of directed migration in which speed and pausing time is managed by the strength of intracellular Ca2+ transients (Hurni et al., 2017). The final stage of migration is characterized by a change to terminal translocation, rise of intrinsic frequencies of Ca2+ transients and appearence of dendrites, a signature of mature post-migratory neurons (Bando et al., 2016; Hurni et al., 2017). Neuronal dendrites spread out to the marginal zone (MZ), the upper limit «border» for radial migration. The MZ is a low cell density layer at birth, and, as the SP, develops rather early synaptic connections due to a local population of more mature Cajal-Retzius neurons (CRs) (Janušonis et al., 2004) and young post-migratory neurons (Bouwman et al., 2004).

CRs are early born tangentially migrating neurons which are best known for Reelin expression and its role as a regulator of terminal translocation and dendritogenesis (O’Dell et al., 2015; Hirota and Nakajima, 2017). CRs precise number and distribution have refined functions in cortical circuits organization. Thickness of apical dendritic tufts and of the MZ depend on CR density, as well as the excitation/inhibition ratio of post-migratory neurons. CRs migration is dependent on NMDARs stimulation and therefore is also activity-dependent (de Frutos et al., 2016; Riva et al., 2019). Two key chemical regulators of multipolar-bipolar and terminal translocation steps, Reelin and Dab1 (Hirota and Nakajima, 2017; Zhang et al., 2018) are surprisingly upregulated by electromagnetic field exposure (Hemmati et al., 2014). Altogether these data suggest that electric currents may be well upstream of chemical regulation of radial neuronal migration.

Is There EF in the Developing Cortex?

The presence of an electrically active boundary during cortical development, which organizes neuronal migration was described by Ohtaka-Maruyama (2020). It is possible to further imagine the developing cortex as a stratified structure of variable electric strength. For instance, the SP and the MZ are possibly highly charged compared to the relatively low EF in the IZ and the cortical plate (CP). They, thus, both could serve as electrical guide borders which, together with chemical cues, help attracting migrating glutamatergic neurons in the direction of the pia, orient their polarization and eventually drive corresponding morphological changes: axon initiation under the SP and dendritogenesis in the MZ.

How could this be exerted mechanistically on the migrating cell? As explained by Yao and Li (2016), when a cell is submitted to EF, due to a large membrane resistance, ionic flow is forced mainly around the cell. This creates extracellular current along the cell sides and lateral voltage gradient along the upper and lower membrane surfaces. Charged lipids and proteins, including conductance channels, are redistributed by the electrophoretic force, and form clusters. Voltage-gated ion channels could respond directly, creating local differences in resting membrane potentials and subsequent stimulation of Ca2+ influx and signaling activation. For example, increase of the Ca2+ influx on one side may signal the cell to form localized lamellipodia (Yao and Li, 2016). The same principle would apply to neurotransmitter-gated ion channels in the presence of neurotransmitter gradients, as discussed in the chapters below.

Some data from related models could support this view. Cao et al. (2014), have shown that EF gradients are present in cultures of SVZ explants from postnatal mice. In their study neuroblasts migration without growth factors is random and cells have multipolar morphologies, but when EF of physiological strength is applied, cells acquire a bipolar morphology and the directionality of migration significantly increases (Cao et al., 2014) – a situation remarkably similar to the multipolar-bipolar switch in the SP. A wealth of studies on the behavior of neural stem cells upon electric stimulation has established an in vitro model that remarkably reminds of the developing cortex organization in the radial axis: in the absence of electric stimulation stem cells self-renew or differentiate into neurons or astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. After EF application they proliferate more efficiently with a shift toward neurons, cells become polarized, migrate toward the cathode and show an increase in intracellular Ca2+ (Bertucci et al., 2019). These observations, collected upon direct electric stimulation on immature neurons, in the absence of chemical stimuli, accurately reproduce complex behaviors of intact young neurons in the developing cortex tissue, and therefore suggest that EF variations are capable of inducing a whole panel of elaborated migration and maturation behaviors of glutamatergic cortical neurons.

Neurotransmitters, Their Receptors and Ion Channels

Migration and dendritogenesis are processes separated both spatially and temporally, suggesting specific mechanisms of regulation. This is true for both tangentially and radially migrating populations. There is a plethora of data on electric modification of cortical neurons leading to migration delays with or without further defects in dendritogenesis. In the following sections, we attempt to dissect possible mechanisms underlying the electric control of migration and dendritogenesis by correlating ion channels distribution and their known effects on these two processes.

Glutamate and Its Receptors

Ambient glutamate concentration in the neonatal cortex is high compared to later postnatal stages, when it is likely uptaken by astrocytes (Hanson et al., 2019). Since neuronal migration and differentiation occurs prior to astrocytic differentiation, which starts at end of the embryonic period, extracellular glutamate concentrations may be even higher at prenatal stages. The source of extracellular glutamate is not exactly known. It can be released when vesicular neurotransmission is blocked and it has been suggested that it acts in a paracrine manner and may be sequestered around migrating neurons (Luhmann et al., 2015). Glutamate has been shown to act as a chemoattractant of cortical neurons in vitro (Behar et al., 1999).

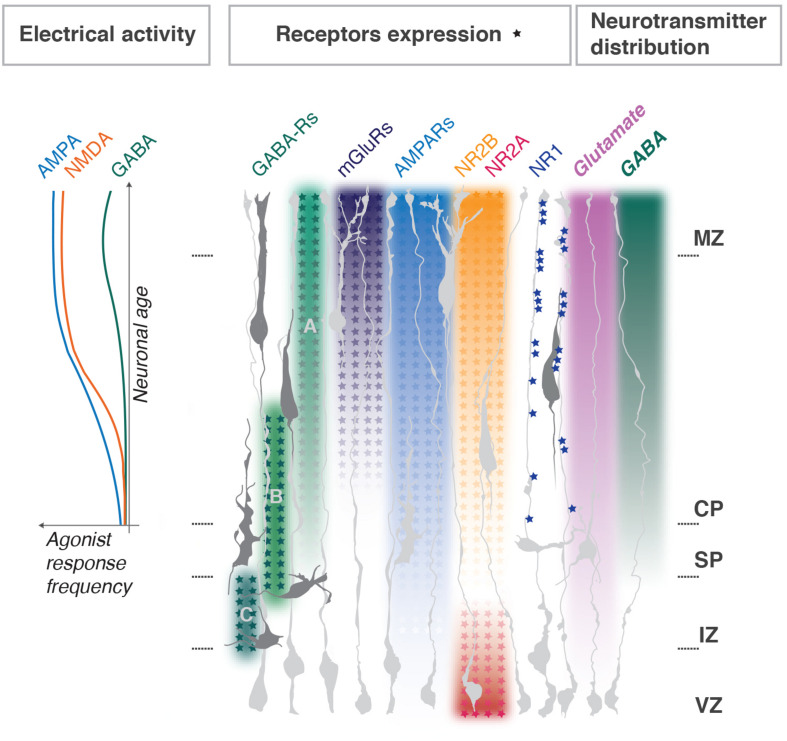

Glutamate receptors, namely NMDARs, AMPARs and mGluRs, are expressed in the developing cortex. However, their subunit distribution throughout the developing cortex is uneven and in some cases, they display a clear developmental switch (Luhmann et al., 2015; Mayer et al., 2019; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of neurotransmitters and their receptors during cortical development. Enrichment gradients of ion channels and their specific subunits as neurons develop correlate with Ca2+ responses to corresponding agonists (graph to the left, adapted from Mayer et al., 2019) and dendritogenesis in the post-migratory neurons. NMDA NR1 subunits clustering in radial glia fibers regulate neuronal layer positioning; NMDA NR2A and B expression switches as progenitors differentiate into neurons. Metabotropic glutamate receptors gradients are representative for mGluRs1, 3, 4, 5, and 8; for AMPARs – GluR1, 2, 3, 4. GABAA, GABAB, and GABAC receptors functional switches in radially migrating neurons are shown. MZ, marginal zone; CP, cortical plate; SP, subplate; IZ, intermediate zone; VZ, ventricular progenitors zone. Major references Hurni et al. (2017), Mayer et al. (2019), and Pasquet et al. (2019).

Many studies on the role of NMDARs and AMPARs in migration are summarized in excellent reviews (Rakic and Komuro, 1995; Luhmann et al., 2015; Horigane et al., 2019; Ojeda and Ávila, 2019). In general, NMDAR and AMPAR blockade attenuates the migration of different types of immature neurons and NMDA physiological activation accelerates the movement. Selective manipulations of both NMDARs or AMPARs subunits by genetic and acute invalidation, however, do not exactly reproduce these effects in radially migrating glutamatergic neurons of the developing cortex, leaving the interpretation still unresolved.

NMDARs Subunits

NR1 (a.k.a. Grin1 or GluN1) is absent from the progenitor zone and present in the CP. It is an essential subunit for NMDAR function, but surprisingly its manipulation does not always lead to dramatic alterations in the developing cortex. Luhmann et al. (2015) review a series of studies on cell-type-specific NR1 knockouts (one good example is Iwasato et al., 2000), which indicate either the existence of compensatory mechanisms or extrinsic regulation of migration by non-neuronal target structures, like glial cells. One recent study supports the latter (Pasquet et al., 2019). Here, the authors demonstrate that proper layering of radially migrating neurons relies on NR1 clustering in radial glia fibers at contact sites with the soma and leading process of bipolar neurons (Figure 2). On the other hand, acute NR1 downregulation (KD) by in utero electroporation (IUE) into neuronal progenitors severely delay the migration of electroporated cells, without changing neuronal fate determination (Jiang et al., 2015). Measurements of dendritic structure of NR1 KD neurons located ectopically in lower cortical layers showed a simplistic morphology, as did controls (siRNA for a motility agent). However, KD neurons which reached the proper layer still showed a simplistic morphology (Jiang et al., 2015). Therefore, NR1 correct expression mediates proper dendritogenesis of post-migratory cortical neurons. Overall it is difficult to uncouple the role for NR1 in both processes. Furthermore, its cell-autonomous role in migrating neurons remains debatable.

NR2A and B (a.k.a. Grin2A,B or GluN2A,B) are modulatory subunits and often undergo a developmental switch in various neural tissues, including the cerebral cortex (Figure 2). The switch sharpens the response to glutamate as it yields channels with faster kinetics which are important for regulation of maturation of neuronal circuits (Mayer et al., 2019). In agreement with the expression pattern, NR2B, but not NR2A, cell-autonomous downregulation impedes radial migration, without changes of neuronal identity. Neurons aberrantly located in lower cortical layers develop dendritic trees of abnormally high complexity, and those neurons which reach the targeted position are comparable to controls (Jiang et al., 2015). Therefore, it is possible that NR2B function in physiological dendritogenesis is related to inhibition of the process. Based on these studies it is hard to uncouple its specific roles in dendritogenesis vs. migration.

Recent reports further highlight a substantial role for NR2B in neuronal maturation, dendritogenesis and non-synaptic NMDAR function. Human neural progenitors carrying autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-associated NR2B variants show impaired Ca2+ influx, membrane depolarization and differentiation failure (Bell et al., 2018). Most of NR2B-containing receptors are found within dendrites and the cortical neurons carrying ASD-associated variants manifest less dendrites, shorter total length and overall dysmorphia, while spine density or morphology is not altered. Mechanistically these mutations abolish channel activity and show no surface expression and reduced delivery to neurites (Sceniak et al., 2019). A more refined mechanism is proposed by a study on hippocampal neurons and cortical spiny stellate cells where dendritic length regulation and branching are uncoupled, with only the latter relying on NR2B (Espinosa et al., 2009).

It is interesting to note that among the known developmental NMDAR-dependent channelopathies it is exactly NR1 and NR2B gain of function variants which cause early developmental migration phenotypes, such as polymicrogyria (Smith and Walsh, 2020). This suggests that gain of function mutations might primarily affect migration in human developmental pathologies.

AMPARs and Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors

AMPA receptors expression increases in cortical neurons throughout development (Hurni et al., 2017; Mayer et al., 2019; Figure 2) and, similarly, to NMDARs, have been involved in both migration and dendritogenesis. Pharmacological studies with the AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist CNQX reveal the role in motility dynamics of migrating neurons; enhanced stalling and directionality changes are explained by lack of coordination between soma and leading process extension, possibly due to problems with growth cone dynamics (Jansson et al., 2013). It is important to mention, however, that CNQX is not exclusively selective for AMPARs but acts as well as NMDARs antagonist at glycine site (Lester et al., 1989), so the described effects are hard to dissociate between the two receptors. There is, however, an important argument against a role for AMPARs in radial migration: out of all glutamate receptor ligands only NMDA and L-glutamate (and not AMPA, D-glutamate, kainate or quisqualate) induce chemotactic motility responses in mouse cortical neurons (Behar et al., 1999).

Dendritic arbor development of glutamatergic neurons and interneurons is mediated by distinct AMPA subunits. GluR1, 2 and 3 are involved in dendritogenesis of glutamatergic cortical neurons and their action is associated with spontaneous increase of Ca2+ transient amplitudes, but not frequency. Few studies report specifically an increase of dendritic arbor complexity at the third level branches and higher (Chen et al., 2009; Hamad et al., 2014). Others detect strong upregulation of dendritic length by subunits “flip” isoforms particularly enriched in development (Hamad et al., 2011). GluR1 (and not −2 and −3) is more specific for interneuron dendritogenesis (Hamad et al., 2011). Indeed, interneurons, migrating in the IZ, become more rounded after AMPA exposure and this is mediated by paracrine AMPA receptor activation (Poluch et al., 2001). Therefore, GluRs might participate in guiding the migratory stream, or provide stop signals for migrating interneurons and initiate their maturation.

One hypothesis for AMPA-regulated Ca2+ dynamics in immature neurons rests on their deficiency in subunits [e.g., GluR2 (GluA2)] which causes cortical neurons to be permeable to Ca2+, while their gradual enrichment toward birth strengthens Ca2+ influx control (Kumar et al., 2002). This is supported by a study in which activation of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors induced neural progenitor cells (NPCs) to differentiate to the neuronal lineage and increased their dendritic arbor formation (Whitney et al., 2008). Overall, AMPARs may be a good candidate for preferential regulation of dendritogenesis over the migratory effects on cortical maturing neurons.

AMPARs actions on dendritogenesis interplay with those of metabotropic glutamate receptors, mGluRs (Grms). One example is the disruption of dendritogenesis in mGluR5 knockout cortical neurons associated with an increase of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors (Huang and Lu, 2018). However, mGluRs also have a role in stalling during neuronal migration, which is believed to be due to highly localized Ca2+ changes and is an important part of migration as it may be rising sensitivity to chemical cues, helping direction searching (Jansson et al., 2013). Although not ionotropic, mGluRs activation seems to be linked to triggering Ca2+ high-amplitude waves propagation (typical for developing tissues) only in subregions of the dendrites (Ross, 2012), and therefore in interaction with AMPARs they could contribute to fine dendritic organization.

GABA and Its Receptors

GABA is one of the earliest neurotransmitters expressed in the nervous system and is enriched during early corticogenesis (Lauder et al., 1986; Behar et al., 1996; Bony et al., 2013). GABA influences radial and tangential migration through its various receptors depending on the migration step and exerts some of these actions through Ca2+ influx signaling, due to the fact that that it functions as an excitatory neurotransmitter in early development and depolarizes immature neurons. GABA paracrine and chemoattractive actions have been documented by several authors (Horigane et al., 2019; Ojeda and Ávila, 2019).

Glutamatergic neurons migration can be modulated by GABA in a concentration-dependent manner and relies on pharmacologically distinct classes of GABA receptors. VZ/IZ populations, show directed migration in response to femtomolar GABA concentrations. Cells which exit from the proliferative zone to the IZ are blocked by GABAC ionotropic channels antagonist, and GABAC-R, which has a high affinity to GABA, delivers a signal that maintains migration throughout the IZ (Behar et al., 1998, 2000; Denter et al., 2010). IZ-CP entry is sensitive to G-protein inhibitors, indicating a role for metabotrophic GABAB G-protein coupled receptors. Neurons migrating in the CP respond to micromolar amounts of GABA with increased cell motility and this response partially relies on G-protein. This is also sensitive to depolarizing agents: glutamate, potassium and GABAA ionotropic channels activation (Behar et al., 1998, 2000). GABAA-R regulates migration speed in the upper CP and most of all is important for migration termination before the MZ with GABA tonically reducing the speed of cell migration in the upper cortex via GABAA-R activation by interfering with Ca2+ oscillations (Heck et al., 2007). GABAA-R-dependent regulation of migration may also be mediated by taurine, a compound abundantly present in developing tissues (Furukawa et al., 2014). Therefore, there is an elegant model on the regulation of radial migration by GABA concentration gradients through receptor expression switches depending on the physiologic state of the migrating neuron, crossing each developmental zone (Figure 2).

After birth young neurons switch response to GABA from excitatory to canonical inhibitory (Ben-Ari et al., 2012). GABA-induced excitability decreases due to lowering of intracellular Cl– concentrations via developmental upregulation of KCC2, a K+/Cl– cotransporter extruder, and downregulation of NKCC1, the chloride-inward Na+-K+-Cl– cotransporter. The GABAA-R-dependent Cl– flux reverts and becomes hyperpolarizing (Bortone and Polleux, 2009; Horigane et al., 2019). This mechanism is at the basis of the termination of interneurons migration. Before the switch, ambient GABA and Glutamate signals are motogenic, but once interneurons are in the cortex the decrease of Ca2+ transients upon GABAA-R activation induces them to stop (Bortone and Polleux, 2009).

For radially migrating neurons excitatory GABA actions exerted through GABAA-R are indispensable for morphological maturation. Premature overexpression of KCC2 as well as downregulation of NKCC1 do not perturb migration (Cancedda et al., 2007; Jiang et al., 2015), but have a dramatic effect on dendritic morphology (Ge et al., 2006). KCC2 overexpression prevents GABA-induced Ca2+ elevation and the morphological impairment of properly positioned upper layer neurons comprises pronounced reduction of total dendrite length and branch number, with very few dendritic processes projecting to layer 1 (MZ). The effect worsens with time. Experiment with overexpression of the inward-rectifier K+ channel Kir2.1 produced similar results, further indicating that reducing membrane depolarization is sufficient to impair dendritogenesis in cortical neurons (Cancedda et al., 2007; Sernagor et al., 2010). However, also direct disruption of GABAA receptor activity without perturbations of cell polarization produces similar effects. DISC1-KD in young cortical pyramidal neurons leads to perturbations of surface expression of the GABAA-R subunit, while Cl– cotransporters are unaffected (Saito et al., 2016). Nonetheless, GABA-mediated Ca2+ influx is diminished, as demonstrated by GABAA-R antagonist treatment. Acute DISC1-KD in postnatal cortical neurons prevents complex dendritic arborization development and this is accompanied by GABA-mediated post-synaptic currents impairments (Saito et al., 2016). Thus, dendritogenesis is mediated by direct GABAA receptor activity as well as by the hyperpolarized state of the neuron.

GABAB metabotropic receptor has been found to be crucial for axon-dendrite polarization and growth. GABAB downregulation in a dose-dependent manner leads to migration delays and ectopic accumulation of cells with long and thin processes, as well as reduced development of dendrites and pronounced axonogenesis in cells reaching the upper CP. In vitro GABAB-R signaling specifically affected axonal initiation. The mechanisms rely on cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of LKB1, a kinase involved in neuronal polarization (Bony et al., 2013). This goes in concordance with the specific receptor role in the IZ-CP transition, which thus may rely on the multipolar-bipolar transition regulation. In tangential migration GABAB has a pronounced role in a concentration-dependent motility regulation, through regulation of the length of the leading process, and those effects are not accompanied by membrane potential changes, highlighting that mechanism does not rely on electric activity modulation (López-Bendito et al., 2003). Therefore, the primary role of GABAB-R is related to neuronal polarization and subsequent directed migration rather than to dendritogenesis.

Other Ion Channels: Are Migration and Dendritogenesis Uncoupled?

Most studies on neurotransmitter channels do not clearly discriminate whether the effects on dendritogenesis are a direct consequence of those on termination of migration. Few interesting examples below illustrate how ion channels, which modulate electrical activity, can regulate migration and dendritogenesis and possibly help the distinction.

Prokaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel, NaChBac, when overexpressed in cortical radially migrating neurons, dramatically raises excitability and the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients. This causes premature migration arrest, but also induce dendritogenesis in ectopic cells. Moreover, the ectopic cells appear to prematurely complete their migration since they loose contact with radial glia fibers. The authors show that migrating neurons have lower Ca2+ oscillations parameters than the post-migratory and thus they hypothesize that the difference between neuronal migration and maturation relies on the intensity of spontaneous Ca2+ transients (Bando et al., 2016). Another study aiming to stimulate cell-intrinsic activity used an artificial receptor-ligand system (DREADD). The results obtained here were overall similar to those of NAChBAc: cells with raised Ca2+ transients frequencies, and not durations, were massively delayed in the IZ-SVZ and lower CP, without changing their birthdate-dependent identity. Moreover, ectopic neurons developed neuritic branching reminiscent of dendrites. The same study, similarly, observed raised Ca2+ transients in neurons undergoing migration termination. Moreover, the authors were able to show that DREADD-induced cell migration delays were associated with an increase in pausing time, and not instant migratory speed (Hurni et al., 2017). These studies reinforce the idea that a developmental increase in Ca2+ events intensity plays a role in migration arrest and, eventually, maturation.

While the above studies are very illustrative, they depend on artificial expression of non-endogenous channels, which probably overstimulate electrical activity to abnormally high levels and thus cannot exactly reflect the physiological situation in the mammalian cortex. A recent study by Smith et al. (2018) addresses the role of SCN3A, a subunit of voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.3, which is naturally enriched in migrating neurons of the developing human cortex and is downregulated upon cortical maturation. Few point variants in this gene are associated with rare cases of developmental channelopathies which range from polymicrogyria and intellectual disability to microcephaly and severe seizures. Acute overexpression of the gene and its mutant forms in the ferret cortex highlighted the role in migration and gyrification (additional sulci and gyri) with heterotopic formations exclusively registered in the case of mutants. Overexpression of SCN3A in human cortical neurons promoted dendritic branching and this effect was attenuated in mutant forms. Patch clamping human fetal cortical neurons demonstrated the absence of action potentials, therefore SCN3A likely contribute to Na+ conductance that modulate other voltage-dependent processes like Ca2+ signaling. Altogether, these data suggest, once again, that dendritic branching and migration effects are closely interconnected. However, it is important to point out that the same variant (F1759Y) which aggravates migration phenotypes (more severe gyrification and heterotopia) also attenuates dendritogenesis which goes in the opposite direction to the postulate that simple neuronal activity overstimulation is ultimately responsible for both processes.

Notably, migration arrest due to enhanced neuronal activation is not always accompanied by dendritogenesis. The KCNK family of leak potassium channels conducts potassium currents at resting membrane potential, with little voltage dependence, and is one of the major determinants of neuronal excitability in the cortex. Family members are expressed throughout the cortex and have a role in radial migration with the most prominent phenotypes observed for KCNK9. KCNK9 downregulation as well as overexpression of mutant forms impair radial migration by increasing the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients, possibly by controlling resting membrane potassium permeability. The ectopic delayed cells do not die neither they change their identity, but persist in deeper cortical layers showing undeveloped morphology for a prolonged period of time (Bando et al., 2014). Since the correct positioning of neurons is crucial for proper dendritogenesis (Martineau et al., 2018), these results imply that KCNK9-induced Ca2+ transients increase is not sufficient to promote ectopic dendritic morphology development, while it is sufficient for the migration arrest.

These few studies demonstrate that although migration, its final termination and dendritogenesis are intimately connected and likely rely on similar mechanisms of electrical activity rise at the maturation stage, the mode of this electrical activity regulation by ion transport type and intensity may vary: from very intense which causes ultimately cell migration arrest and strong ectopic dendritogenesis (like stimulation with DREADD) to milder which only affects migration (like KD of KCNK9). Moreover, it is possible that channel conformation changes due to mutations contribute to its activity and somehow regulates migration and dendritogenesis in opposing manner, as it seems to happen with SCN3A pathological variants.

Synaptogenesis and “Synaptic” Proteins

It is generally believed that functional chemical synapses massively appear within the first 2 weeks after birth. However, the exact time of establishment of fully functional synaptic structures is somehow vague. Synapses are complex and comprise many molecules which are supposed to be specific, but have a remarkably variable expression span and, often, functionality (Farhy-Tselnicker and Allen, 2018; Südhof, 2018).

The developing mouse cortex gradually shapes morphologically recognizable synapses. First clearly immature synapses (with pleiomorphic vesicles associating around newly formed terminals, with yet thin pre- and post-synaptic plasmalemmas and narrow gap in between) are identifiable as early as E15 (Li et al., 2010). Functional synapses likely appear in electrically active borders such as the SP and MZ (Figure 1). SP neurons forming full synaptic connections with multipolar migrating neurons were observed at E16 in mice (Ohtaka-Maruyama et al., 2018). These connections are defined (i) morphologically by VGLUT2 staining, and the presence of vesicles and electron-dense structures reminiscent of active zones and post-synaptic densities, and (ii) functionally by the presence of Ca2+ transients and exocytosis of presynaptic vesicles at the upper IZ. However, data suggest that these functional synapses may be present earlier (Ohtaka-Maruyama et al., 2018). SP neurons may also send electrophysiologically active GABAergic projections to CR cells in the MZ as seen soon after birth (Myakhar et al., 2011), but synaptogenesis on CRs is described already at E17 (Janušonis et al., 2004).

Morphological synapses in the MZ, which are largely formed by two classes of neurons, are registered as early as E16 in mice. Their ultrastructure satisfies the parameters of morphologically well-formed mature synapses: presynaptic vesicles conglomeration, presence of docked vesicles and active zone. By E18, MZ abundantly expresses a list of structural synaptic proteins, including post-synaptic density marker PSD95, synaptic vesicle associated VAMP2, and AMPA subunits 2 and 3. However, the functionality of these synapses may not be fully established yet: in the absence of neurotransmitter release and, thus, synaptic electric activity (Munc18-1 null mice) these synapses are largely preserved (Verhage et al., 2000; Bouwman et al., 2004). A structurally complete synapse, therefore, does not necessarily mean it is electrophysiologically functional and, in fact, may not require electrical activity to be formed.

Many synaptic molecules are expressed in the developing cerebral cortex prior to full synaptic formation. What could be their function? One example is the VAMP-family proteins, controlling migration speed in CRs, as early as E11, possibly through regulation of exocytosis, asymmetric membrane transport and/or endosomal recycling. This function turns out to be dramatically important for regulation of cortical arealization during postnatal development, specifically for primary and secondary sensory cortices and its connection routing (Barber et al., 2015). Another example comprises the whole class of trans-synaptic cell-adhesion molecules (CAMs). CAMs are likely at the basis of primary organization of synaptic junctions, but along with that they are as numerous and efficient for synaptogenesis as they are multifunctional outside this process. CAMs families such as LAR-type RPTPs and their ligands, Slitrks, Cadherins, Teneurins, and Ephrins/Eph receptors are all involved in neuronal morphogenesis, both dendritogenesis and axonal pathfinding (Südhof, 2018). Interesting confluence of CAMs role on both morphogenesis and organization of electrical activity zones, such as the synapses, is reminiscent of gradual Ca2+ transients rise and morphological refinement of maturing migrating neurons. Few examples of CAMs regulation of neuronal migration exist (Qu and Smith, 2004; Kirkham et al., 2006; Funato et al., 2011; Sentürk et al., 2011; Puehringer et al., 2013; del Toro et al., 2017, 2020), however, whether the mechanisms involve electrical activity regulation remains an open question.

Conclusion

In this review, we have discussed the distribution of ion channels canonically involved in the synaptic ion exchange machinery, in the attempt to decipher the principles of electric regulation of migration and maturation in early cortical development, before functional synaptogenesis occurs. While not all neurotransmitter receptor systems involved in the maturation of developing pyramidal neurons were considered (such as purinergic and cholinergic systems), a basic coupling principle seems to predominate: channels underlining excitatory responses and thus electrical cellular activation (with Ca2+ transients as a readout) contribute to migration pausing, eventual arrest and subsequent dendritogenesis (Table 1). Although it is hard to clearly correlate particular channels presence with dendritogenesis vs. migration arrest, progressive enrichment of specifically the NR2B subunit of NMDA receptors as well as the appearance of fast excitatory transmission supplied by AMPARs expression seem to be the most promising candidates for electrical regulation of initial neuronal maturation.

TABLE 1.

Summary of ion channels having differential roles in migration and dendritogenesis of cortical glutamatergic neurons.

| Migration | Dendritogenesis | References | |

| NMDA NR1 | Yes | Basic expression levels are needed for proper dendrite arborization | Jiang et al., 2015 |

| NMDA NR2B | Yes | Primary dendrite pruning and patterning | Espinosa et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2015 |

| AMPA GluR1, 2, 3 | Yes* | Arborization length and complexity | Chen et al., 2009; Jansson et al., 2013; Hamad et al., 2014 |

| NKCC1 | No | Possibly. Effects on dendritic arborization in young hippocampal granule cells | Ge et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2015 |

| KCC2 | No | Premature expression disrupts dendritogenesis | Cancedda et al., 2007 |

| Kir2.1 | No* | Premature expression disrupts dendritogenesis | Cancedda et al., 2007 |

| SCN3A | Yes | Pathological variant attenuates dendritogenesis, but not migration | Smith et al., 2018 |

| KCNK9 | Yes | No | Bando et al., 2014 |

*Alternative interpretations still possible (see text).

Dendritogenesis is concurrent with synaptogenesis, and according to the synaptotrophic hypothesis, synaptogenesis comes first and is initially required for filopodia stabilization. The very first step in this process is recruitment of CAMs which subsequently leads to gradual synapse formation and dendritic stabilization and outgrowth (Chen and Haas, 2011). It is now explicitly demonstrated that functional synaptic contacts in the developing cortex help migration pausing and morphological reorganization during the multipolar-bipolar transition in proximity of the electrically mature zone, the SP (Ohtaka-Maruyama et al., 2018). However, how advanced the synaptic machinery assemblage must really be in order to assert proper electrical regulation of migration and maturation processes is unclear. As well as neurotransmitters and their receptors, CAMs expression throughout the early developing cortex is abundant and there are examples where partners for synaptic binding are expressed in complementary manner in areas formally devoid of synaptic structures. Further investigations are needed to fully answer the intriguing questions of how the congregation of synaptic molecules regulates neuronal maturation, whether this relies on adhesive or electric-organizing properties of CAMs or their combination, and how the neuronal electrical and adhesive machinery cooperate during cortical development.

Author Contributions

VM and AP conceived and wrote the review. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Sonia Garel, Frédéric Causeret, Eva Coppola and Cataldo Schietroma for critical reading and very helpful comments.

Footnotes

Funding. VM was supported by the Fondation Imagine (ANR-10-IAHU-01) and AP was a CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) Investigator. This work was supported by grants from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-15-CE16-0003-01), FRM («Equipe FRM DEQ20130326521«), and Fondation de France (00081243).

References

- Arai Y., Pierani A. (2014). Development and evolution of cortical fields. Neurosci. Res. 86 66–76. 10.1016/j.neures.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikkath J. (2012). Molecular mechanisms of dendrite morphogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 6:61. 10.3389/fncel.2012.00061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando Y., Hirano T., Tagawa Y. (2014). Dysfunction of KCNK potassium channels impairs neuronal migration in the developing mouse cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 24 1017–1029. 10.1093/cercor/bhs387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando Y., Irie K., Shimomura T., Umeshima H., Kushida Y., Kengaku M., et al. (2016). Control of spontaneous Ca 2+ transients is critical for neuronal maturation in the developing neocortex. Cereb. Cortex 26 106–117. 10.1093/cercor/bhu180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber M., Arai Y., Morishita Y., Vigier L., Causeret F., Borello U., et al. (2015). Migration speed of cajal-retzius cells modulated by vesicular trafficking controls the size of higher-order cortical areas. Curr. Biol. 25 2466–2478. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber M., Pierani A. (2016). Tangential migration of glutamatergic neurons and cortical patterning during development: lessons from Cajal-Retzius cells. Dev. Neurobiol. 76 847–881. 10.1002/dneu.22363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar T. N., Li Y. X., Tran H. T., Ma W., Dunlap V., Scott C., et al. (1996). GABA stimulates chemotaxis and chemokinesis of embryonic cortical neurons via calcium-dependent mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 16 1808–1818. 10.1523/jneurosci.16-05-01808.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar T. N., Schaffner A. E., Scott C. A., Greene C. L., Barker J. L. (2000). GABA receptor antagonists modulate postmitotic cell migration in slice cultures of embryonic rat cortex. Cereb. Cortex 10 899–909. 10.1093/cercor/10.9.899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar T. N., Schaffner A. E., Scott C. A., O’Connell C., Barker J. L. (1998). Differential response of cortical plate and ventricular zone cells to GABA as a migration stimulus. J. Neurosci. 18 6378–6387. 10.1523/jneurosci.18-16-06378.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar T. N., Scott C. A., Greene C. L., Wen X., Smith S. V., Maric D., et al. (1999). Glutamate acting at NMDA receptors stimulates embryonic cortical neuronal migration. J. Neurosci. 19 4449–4461. 10.1523/jneurosci.19-11-04449.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S., Maussion G., Jefri M., Peng H., Theroux J. F., Silveira H., et al. (2018). Disruption of GRIN2B impairs differentiation in human neurons. Stem Cell Rep. 11 183–196. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Woodin M., Sernagor E., Cancedda L., Vinay L., Rivera C., et al. (2012). Refuting the challenges of the developmental shift of polarity of GABA actions: GABA more exciting than ever!. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 6:35. 10.3389/fncel.2012.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertucci C., Koppes R., Dumont C., Koppes A. (2019). Neural responses to electrical stimulation in 2D and 3D in vitro environments. Brain Res. Bull. 152 265–284. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bony G., Szczurkowska J., Tamagno I., Shelly M., Contestabile A., Cancedda L. (2013). Non-hyperpolarizing GABAB receptor activation regulates neuronal migration and neurite growth and specification by cAMP/LKB1. Nat. Commun. 4:1800. 10.1038/ncomms2820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortone D., Polleux F. (2009). KCC2 expression promotes the termination of cortical interneuron migration in a voltage-sensitive calcium-dependent manner. Neuron 62 53–71. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwman J., Maia A. S., Camoletto P. G., Posthuma G., Roubos E. W., Oorschot V. M. J., et al. (2004). Quantification of synapse formation and maintenance in vivo in the absence of synaptic release. Neuroscience 126 115–126. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda L., Fiumelli H., Chen K., Poo M. (2007). Excitatory GABA action is essential for morphological maturation of cortical neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 27 5224–5235. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5169-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Pu J., Scott R. H., Ching J., Mccaig C. D. (2014). Physiological electrical signals promote chain migration of neuroblasts by up-regulating P2Y1 purinergic receptors and enhancing cell adhesion. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 11 75–86. 10.1007/s12015-014-9524-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Wei D., Reid B., Zhao S., Pu J., Pan T., et al. (2013). Endogenous electric currents might guide rostral migration of neuroblasts. EMBO Rep. 14 184–190. 10.1038/embor.2012.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. X., Haas K. (2011). Function directs form of neuronal architecture. Bioarchitecture 1 2–4. 10.4161/bioa.1.1.14429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Prithviraj R., Mahnke A. H., McGloin K. E., Tan J. W., Gooch A. K., et al. (2009). AMPA glutamate receptor subunits 1 and 2 regulate dendrite complexity and spine motility in neurons of the developing neocortex. Neuroscience 159 172–182. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chighizola M., Dini T., Lenardi C., Milani P., Podestà A., Schulte C. (2019). Mechanotransduction in neuronal cell development and functioning. Biophys. Rev. 11 701–720. 10.1007/s12551-019-00587-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corlew R., Bosma M. M., Moody W. J. (2004). Spontaneous, synchronous electrical activity in neonatal mouse cortical neurones. J. Physiol. 560 377–390. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Frutos C. A., Bouvier G., Arai Y., Thion M. S., Lokmane L., Keita M., et al. (2016). Reallocation of olfactory cajal-retzius cells shapes neocortex architecture. Neuron 92 435–448. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Toro D., Carrasquero-Ordaz M. A., Chu A., Ruff T., Shahin M., Jackson V. A., et al. (2020). Structural basis of teneurin-latrophilin interaction in repulsive guidance of migrating neurons. Cell 180 323.e–339.e. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Toro D., Ruff T., Cederfjäll E., Villalba A., Seyit-Bremer G., Borrell V., et al. (2017). Regulation of cerebral cortex folding by controlling neuronal migration via FLRT adhesion molecules. Cell 169 621–635.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denter D. G., Heck N., Riedemann T., White R., Kilb W., Luhmann H. J. (2010). GABAC receptors are functionally expressed in the intermediate zone and regulate radial migration in the embryonic mouse neocortex. Neuroscience 167 124–134. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egorov A. V., Draguhn A. (2013). Development of coherent neuronal activity patterns in mammalian cortical networks: common principles and local hetereogeneity. Mech. Dev. 130 412–423. 10.1016/j.mod.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa J. S., Wheeler D. G., Tsien R. W., Luo L. (2009). Uncoupling dendrite growth and patterning: single-cell knockout analysis of NMDA receptor 2B. Neuron 62 205–217. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhy-Tselnicker I., Allen N. J. (2018). Astrocytes, neurons, synapses: a tripartite view on cortical circuit development. Neural Dev. 13 1–12. 10.1186/s13064-018-0104-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J. F., Liu J., Zhang L., Jiang J. Y., Russell M., Lyeth B. G., et al. (2017). Electrical guidance of human stem cells in the rat brain. Stem Cell Rep. 9 177–189. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J.-F., Liu J., Zhang X.-Z., Zhang L., Jiang J.-Y., Nolta J., et al. (2012). Guided migration of neural stem cells derived from human embryonic stem cells by an electric field. Stem Cells 30 349–355. 10.1002/stem.779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funato K., Yamazumi Y., Oda T., Akiyama T. (2011). Tyrosine phosphatase PTPRD suppresses colon cancer cell migration in coordination with CD44. Exp. Ther. Med. 2 457–463. 10.3892/etm.2011.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T., Yamada J., Akita T., Matsushima Y., Yanagawa Y., Fukuda A. (2014). Roles of taurine-mediated tonic GABAA receptor activation in the radial migration of neurons in the fetal mouse cerebral cortex. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:88. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S., Goh E. L. K., Sailor K. A., Kitabatake Y., Ming G. L., Song H. (2006). GABA regulates synaptic integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Nature 439 589–593. 10.1038/nature04404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad M. I. K., Jack A., Klatt O., Lorkowski M., Strasdeit T., Kott S., et al. (2014). Type I TARPs promote dendritic growth of early postnatal neocortical pyramidal cells in organotypic cultures. Development 141 1737–1748. 10.1242/dev.099697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad M. I. K., Ma-Högemeier Z. L., Riedel C., Conrads C., Veitinger T., Habijan T., et al. (2011). Cell class-specific regulation of neocortical dendrite and spine growth by AMPA receptor splice and editing variants. Development 138 4301–4313. 10.1242/dev.071076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A. H., Duellberg C., Mieck C., Loose M., Hippenmeyer S. (2017). Cell polarity in cerebral cortex development—cellular architecture shaped by biochemical networks. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:176. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson E., Armbruster M., Lau L. A., Sommer M. E., Klaft Z. J., Swanger S. A., et al. (2019). Tonic activation of GluN2C/GluN2D-containing NMDA receptors by ambient glutamate facilitates cortical interneuron maturation. J. Neurosci. 39 3611–3626. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1392-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatanaka Y., Yamauchi K. (2013). Excitatory cortical neurons with multipolar shape establish neuronal polarity by forming a tangentially oriented axon in the intermediate zone. Cereb. Cortex 23 105–113. 10.1093/cercor/bhr383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck N., Kilb W., Reiprich P., Kubota H., Furukawa T., Fukuda A., et al. (2007). GABA-A receptors regulate neocortical neuronal migration in vitro and in vivo. Cereb. Cortex 17 138–148. 10.1093/cercor/bhj135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati M., Mashayekhi F., Firouzi F., Ashori M., Mashayekhi H. (2014). Effects of electromagnetic fields on reelin and Dab1 expression in the developing cerebral cortex. Neurol. Sci. 35 1243–1247. 10.1007/s10072-014-1690-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y., Nakajima K. (2017). Control of neuronal migration and aggregation by reelin signaling in the developing cerebral cortex. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 5:40. 10.3389/fcell.2017.00040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horigane S. I., Ozawa Y., Yamada H., Takemoto-Kimura S. (2019). Calcium signalling: a key regulator of neuronal migration. J. Biochem. 165 401–409. 10.1093/jb/mvz012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.-Y., Lu H.-C. (2018). mGluR5 tunes NGF/TrkA signaling to orient spiny stellate neuron dendrites toward thalamocortical axons during whisker-barrel map formation. Cereb. Cortex 28 1991–2006. 10.1093/cercor/bhx105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurni N., Kolodziejczak M., Tomasello U., Badia J., Jacobshagen M., Prados J., et al. (2017). Transient cell-intrinsic activity regulates the migration and laminar positioning of cortical projection neurons. Cereb. Cortex 27 3052–3063. 10.1093/cercor/bhx059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa S. N., Babona-Pilipos R., Morshead C. M. (2017). Environmental factors that influence stem cell migration: an “electric Field.”. Stem Cells Int. 2017:4276927. 10.1155/2017/4276927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasato T., Datwani A., Wolf A. M., Nishiyama H., Taguchi Y., Tonegawa S., et al. (2000). Cortex-restricted disruption of NMDAR1 impairs neuronal patterns in the barrel cortex. Nature 406 726–731. 10.1038/35021059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshahi A., Schonfeld L., Janssen M. L. F., Hescham S., Kocabicak E., Steinbusch H. W. M., et al. (2013). Electrical stimulation of the motor cortex enhances progenitor cell migration in the adult rat brain. Exp. Brain Res. 231 165–177. 10.1007/s00221-013-3680-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson L. C., Louhivuori L., Wigren H. K., Nordström T., Louhivuori V., Castrén M. L., et al. (2013). Effect of glutamate receptor antagonists on migrating neural progenitor cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 37 1369–1382. 10.1111/ejn.12152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janušonis S., Gluncic V., Rakic P. (2004). Early serotonergic projections to Cajal-Retzius cells: relevance for cortical development. J. Neurosci. 24 1652–1659. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4651-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Jiang W., Zou J., Wang B., Yu M., Pan Y., et al. (2015). The GluN2B subunit of N-methy-D-asparate receptor regulates the radial migration of cortical neurons in vivo. Brain Res. 1610 20–32. 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham D. L., Pacey L. K. K., Axford M. M., Siu R., Rotin D., Doering L. C. (2006). Neural stem cells from protein tyrosine phosphatase sigma knockout mice generate an altered neuronal phenotype in culture. BMC Neurosci. 7:50. 10.1186/1471-2202-7-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konur S., Ghosh A. (2005). Calcium signaling and the control of dendritic development. Neuron 46 401–405. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. S., Bacci A., Kharazia V., Huguenard J. R. (2002). A developmental switch of AMPA receptor subunits in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 22 3005–3015. 10.1523/jneurosci.22-08-03005.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanoue V., Cooper H. M. (2019). Branching mechanisms shaping dendrite architecture. Dev. Biol. 451 16–24. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder J. M., Han V. K. M., Henderson P., Verdoorn T., Towle A. C. (1986). Prenatal ontogeny of the gabaergic system in the rat brain: an immunocytochemical study. Neuroscience 19 465–493. 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90275-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledda F., Paratcha G. (2017). Mechanisms regulating dendritic arbor patterning. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74 4511–4537. 10.1007/s00018-017-2588-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester R. A. J., Quarum M. L., Parker J. D., Weber E., Jahr C. E. (1989). Interaction of 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione with the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-associated glycine binding site. Mol. Pharmacol. 35 565–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M., Pezzulo G., Finkelstein J. M. (2017). Endogenous bioelectric signaling networks: exploiting voltage gradients for control of growth and form. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 19 353–387. 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071114-040647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Cui Z., Niu Y., Liu B., Fan W., Yu D., et al. (2010). Synaptogenesis in the developing mouse visual cortex. Brain Res. Bull. 81 107–113. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Weiss M., Yao L. (2014). Directed migration of embryonic stem cell-derived neural cells in an applied electric field. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 10 653–662. 10.1007/s12015-014-9518-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Bendito G., Luján R., Shigemoto R., Ganter P., Paulsen O., Molnár Z. (2003). Blockade of GABAB receptors alters the tangential migration of cortical neurons. Cereb. Cortex 13 932–942. 10.1093/cercor/13.9.932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann H. J., Fukuda A., Kilb W. (2015). Control of cortical neuronal migration by glutamate and GABA. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:4. 10.3389/fncel.2015.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann H. J., Kirischuk S., Kilb W. (2018). The superior function of the subplate in early neocortical development. Front. Neuroanat. 12:97. 10.3389/fnana.2018.00097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martineau F. S., Sahu S., Plantier V., Buhler E., Schaller F., Fournier L., et al. (2018). Correct laminar positioning in the neocortex influences proper dendritic and synaptic development. Cereb. Cortex 28 2976–2990. 10.1093/cercor/bhy113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer S., Chen J., Velmeshev D., Mayer A., Eze U. C., Bhaduri A., et al. (2019). Multimodal single-cell analysis reveals physiological maturation in the developing human neocortex. Neuron 102 143–158.e7. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaig C. D., Rajnicek A. M., Song B., Zhao M. (2005). Controlling cell behavior electrically: current views and future potential. Physiol. Rev. 85 943–978. 10.1152/physrev.00020.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaig C. D., Song B., Rajnicek A. M. (2009). Electrical dimensions in cell science. J. Cell Sci. 122 4267–4276. 10.1242/jcs.023564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. R., Zhou W. L., Jakovcevski I., Zecevic N., Antic S. D. (2011). Spontaneous electrical activity in the human fetal cortex in vitro. J. Neurosci. 31 2391–2398. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3886-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myakhar O., Unichenko P., Kirischuk S. (2011). GABAergic projections from the subplate to Cajal-Retzius cells in the neocortex. Neuroreport 22 525–529. 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32834888a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell R. S., Cameron D. A., Zipfel W. R., Olson E. C. (2015). Reelin prevents apical neurite retraction during terminal translocation and dendrite initiation. J. Neurosci. 35 10659–10674. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1629-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaka-Maruyama C. (2020). Subplate neurons as an organizer of mammalian neocortical development. Front. Neuroanat. 14:8. 10.3389/fnana.2020.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaka-Maruyama C., Okado H. (2015). Molecular pathways underlying projection neuron production and migration during cerebral cortical development. Front. Neurosci. 9:447. 10.3389/fnins.2015.00447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaka-Maruyama C., Okamoto M., Endo K., Oshima M., Kaneko N., Yura K., et al. (2018). Synaptic transmission from subplate neurons controls radial migration of neocortical neurons. Science 360 313–317. 10.1126/science.aar2866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda J., Ávila A. (2019). Early actions of neurotransmitters during cortex development and maturation of reprogrammed neurons. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 11:33. 10.3389/fnsyn.2019.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquet N., Douceau S., Naveau M., Lesept F., Louessard M., Lebouvier L., et al. (2019). Tissue-type plasminogen activator controlled corticogenesis through a mechanism dependent of NMDA receptors expressed on radial glial cells. Cereb. Cortex 29 2482–2498. 10.1093/cercor/bhy119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picken Bahrey H. L., Moody W. J. (2003). Early development of voltage-gated ion currents and firing properties in neurons of the mouse cerebral cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 89 1761–1773. 10.1152/jn.00972.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poluch S., Drian M. J., Durand M., Astier C., Benyamin Y., König N. (2001). AMPA receptor activation leads to neurite retraction in tangentially migrating neurons in the intermediate zone of the rat neocortex. J. Neurosci. Res. 63 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puehringer D., Orel N., Lüningschrör P., Subramanian N., Herrmann T., Chao M. V., et al. (2013). EGF transactivation of Trk receptors regulates the migration of newborn cortical neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 16 407–415. 10.1038/nn.3333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Q., Smith F. I. (2004). Alpha-dystroglycan interactions affect cerebellar granule neuron migration. J. Neurosci. Res. 76 771–782. 10.1002/jnr.20129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P., Komuro H. (1995). The role of receptor/channel activity in neuronal cell migration. J. Neurobiol. 26 299–315. 10.1002/neu.480260303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers G. J. A., Avci B., Van Hulten P., Van Ooyen A., Van Pelt J., Pool C. W., et al. (2001). The role of calcium signaling in early axonal and dendritic morphogenesis of rat cerebral cortex neurons under non-stimulated growth conditions. Dev. Brain Res. 126 163–172. 10.1016/S0165-3806(00)00148-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash B. G., Ackman J. B., Rakic P. (2016). Bidirectional radial Ca(2+) activity regulates neurogenesis and migration during early cortical column formation. Sci. Adv. 2:e1501733. 10.1126/sciadv.1501733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva M., Genescu I., Habermacher C., Orduz D., Ledonne F., Rijli F. M., et al. (2019). Activity-dependent death of transient cajal-retzius neurons is required for functional cortical wiring. Elife 8:e50503. 10.7554/eLife.50503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross W. N. (2012). Understanding calcium waves and sparks in central neurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13 157–168. 10.1038/nrn3168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A., Taniguchi Y., Rannals M. D., Merfeld E. B., Ballinger M. D., Koga M., et al. (2016). Early postnatal GABAA receptor modulation reverses deficits in neuronal maturation in a conditional neurodevelopmental mouse model of DISC1. Mol. Psychiatry 21 1449–1459. 10.1038/mp.2015.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sceniak M. P., Fedder K. N., Wang Q., Droubi S., Babcock K., Patwardhan S., et al. (2019). An autism-associated mutation in GluN2B prevents NMDA receptor trafficking and interferes with dendrite growth. J. Cell Sci. 132:jcs232892. 10.1242/jcs.232892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentürk A., Pfennig S., Weiss A., Burk K., Acker-Palmer A. (2011). Ephrin Bs are essential components of the Reelin pathway to regulate neuronal migration. Nature 472 356–360. 10.1038/nature09874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sernagor E., Chabrol F., Bony G., Cancedda L. (2010). Gabaergic control of neurite outgrowth and remodeling during development and adult neurogenesis: general rules and differences in diverse systems. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 4:11. 10.3389/fncel.2010.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M. B., White J. A., McKimm E. J., Milosevic M. M., Antic S. D. (2019). Mechanisms of spontaneous electrical activity in the developing cerebral cortex—mouse subplate zone. Cereb. Cortex 29 3363–3379. 10.1093/cercor/bhy205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. S., Kenny C. J., Ganesh V., Jang A., Borges-Monroy R., Partlow J. N., et al. (2018). Sodium channel SCN3A (NaV1.3) regulation of human cerebral cortical folding and oral motor development. Neuron 99 905–913.e7. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.07.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. S., Walsh C. A. (2020). Ion channel functions in early brain development. Trends Neurosci. 43 103–114. 10.1016/j.tins.2019.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solecki D. J. (2012). Sticky situations: recent advances in control of cell adhesion during neuronal migration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22 791–798. 10.1016/j.conb.2012.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer N. C. (2006). Electrical activity in early neuronal development. Nature 444 707–712. 10.1038/nature05300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Südhof T. C. (2018). Towards an understanding of synapse formation. Neuron 100 276–293. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H., Nakajima K. (2003). Multipolar migration: the third mode of radial neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 23 9996–10001. 10.1523/jneurosci.23-31-09996.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang-Schomer M. D. (2018). 3D axon growth by exogenous electrical stimulus and soluble factors. Brain Res. 1678 288–296. 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlen P., Fritz N., Smedler E., Malmersjo S., Kanatani S. (2015). Calcium signaling in neocortical development. Inc. Dev. Neurobiol. 75 360–368. 10.1002/dneu.22273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valnegri P., Puram S. V., Bonni A. (2015). Regulation of dendrite morphogenesis by extrinsic cues. Trends Neurosci. 38 439–447. 10.1016/j.tins.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhage M., Maia A. S., Plomp J. J., Brussaard A. B., Heeroma J. H., Vermeer H., et al. (2000). Synaptic assembly of the brain in the absence of neurotransmitter secretion. Science 287 864–869. 10.1126/science.287.5454.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney N. P., Peng H., Erdmann N. B., Tian C., Monaghan D. T., Zheng J. C. (2008). Calcium-permeable AMPA receptors containing Q/R-unedited GluR2 direct human neural progenitor cell differentiation to neurons. FASEB J. 22 2888–2900. 10.1096/fj.07-104661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L., Li Y. (2016). The role of direct current electric field-guided stem cell migration in neural regeneration. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 12 365–375. 10.1007/s12015-016-9654-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L., McCaig C. D., Zhao M. (2009). Electrical signals polarize neuronal organelles, direct neuron migration, and orient cell division. Hippocampus 19 855–868. 10.1002/hipo.20569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L., Shanley L., McCaig C., Zhao M. (2008). Small applied electric fields guide migration of hippocampal neurons. J. Cell. Physiol. 216 527–535. 10.1002/jcp.21431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuryev M., Andriichuk L., Leiwe M., Jokinen V., Carabalona A., Rivera C. (2018). In vivo two-photon imaging of the embryonic cortex reveals spontaneous ketamine-sensitive calcium activity. Sci. Rep. 8 1–13. 10.1038/s41598-018-34410-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuryev M., Pellegrino C., Jokinen V., Andriichuk L., Khirug S., Khiroug L., et al. (2016). In vivo calcium imaging of evoked calcium waves in the embryonic cortex. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:500. 10.3389/fncel.2015.00500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Wang W., Zhang Z., Hu Y., Meng F., Wang F., et al. (2018). Alternative splicing of disabled-1 controls multipolar-to-bipolar transition of migrating neurons in the neocortex. Cereb. Cortex 28 3457–3467. 10.1093/cercor/bhx212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]