Abstract

In this study, we present the synthesis of novel pyridazin-3(2H)-one derivative namely (E)-4-(4-methylbenzyl)-6-styrylpyridazin-3(2H)-one (MBSP). The chemical structure of MBSP was characterized using spectroscopic techniques such as FT-IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, UV–Vis, ESI-MS, and finally, the structure was confirmed by single X-ray diffraction studies. The DFT calculation was performed to compare the gas-phase geometry of the title compound to the solid-phase structure of the title compound. Furthermore, a comparative study between theoretical UV–Vis, IR, 1H- and 13C NMR spectra of the studied compound and experimental ones have been carried out. The thermal behavior and stability of the compound were analyzed by using TGA and DTA techniques which revealed that the compound is thermostable up to its melting point. Finally, the in silico docking and ADME studies are performed to investigate whether MBSP is a potential therapeutic for COVID-19.

Keywords: Synthesis; Pyridazin-3(2h)-one; Crystal structure, DFT, Hirshfeld surface; Thermal analysis; Molecular docking

1. Introduction

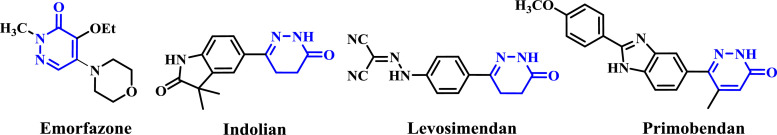

Pyridazin-3(2H)-ones are a very important family of bi-nitrogen aromatic heterocycles. They occupy a very important place in heterocyclic chemistry due to their great chemical reactivity [1] allowing access to a multitude of new products of this family [2,3]. Besides, to their chemical reactivity, the place of pyridazinones in medicinal chemistry has not ceased to increase in recent years, due to their wide range of products with interesting pharmacological activities such as anticancer, anti-hypertensive, antibacterial, anti-HIV, antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, antidepressants, anti-convulsant, cardiotonic and diuretics [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Moreover, several pyridazinone-based products are already present in the pharmaceutical market such as Minaprine, Azanrinone, Emorfazone, Indolidan, Levosimendan, Primobendan, and Bemoradan [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19] (Fig. 1 ). Furthermore, many studies have shown that pyridazinones are good corrosion inhibitors [20] and that they can be used as organic extractants of certain metal ions in the aqueous phase [21]. Due to the numerous biological and therapeutic properties of the pyridazin-3(2H)-ones, the synthesis and investigation of new pyridazinone derivatives have attracted considerable attention from researchers and have been the subject of many studies such as physical, chemical, spectroscopic, and pharmacological properties [22], [23], [24], [25]. Given the importance of these derivatives, the studies of the geometric and electronic properties of pyridazin-3(2H)-ones are essential to know the influence of different groups on structures to discover the relationship of these groups with their pharmacological properties. In particular, computational approaches constitute a solid complement to experimental data for the interpretation of results. Density functional theory (DFT) has become a very important and frequently used tool for researching experimental data and in studies of biological systems. A varied range of calculations using DFT helps to develop a close relationship between theoretical and experimental data by giving clues related to molecular geometry, electrical and spectroscopic properties. These techniques have become very reliable in predicting the properties of molecules with great precision [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]. In a continuation of our efforts to obtain new pyridazin-3(2H)-one compounds [21,[31], [32], [33]], we were inspired to design and synthesize (E)−4-(4-methylbenzyl)−6-styrylpyridazin-3(2H)-one (MBSP). The chemical structure attributed to the title molecule was characterized using FT-IR, UV–vis, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, ESI-MS, and the (E)-configuration was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Besides, DFT calculations were performed to compare the gas-phase structure with the solid-phase one of the title compound. Furthermore, the theoretical UV–Vis and IR spectra of the studied compound were also obtained to compare with the experimental ones. The electronic characters and molecular geometry of the target compound were explored with the aid of DFT calculations. The Hirshfeld surface analysis was executed for the title molecule. Also, TGA/DTA thermal analyses were studied.

Fig. 1.

Example of drugs with pyridazinone ring.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus from the family Coronaviridae, was detected in Wuhan, China. It has caused an associated disease, COVID-19. Common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Other symptoms may include fatigue, muscle pain, diarrhea, sore throat, loss of smell, and abdominal pain [34]. As aforementioned, some pyridazinone derivatives have pharmaceutical potentials. Therefore, the in silico docking and ADME study are adopted to investigate whether the title compound is a potential therapeutic for COVID-19.

2. Experimental section

2.1. General methods

The reaction was checked with TLC using aluminum sheets with silica gel 60 F254 from Merck. The Melting point was measured using a Tottoli digital capillary melting point apparatus and uncorrected. The FT-IR spectrum was recorded with Perkin-Elmer Pargamon 1000 PC FT-IR spectrometer over the range 400–4000 cm−1. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in the DMSO‑d6 solution on a Bruker Avance DPX250 spectrometer. The chemical shifts are expressed in parts per million (ppm) from tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal reference. The Mass spectrum was obtained using an AB SCIEX API 3000 LC/MS/MS system equipped with an ESI source. TGA/DTA curves were recorded in a platinum crucible in a pure air atmosphere at a flow rate of 20 mL/min and over-temperature range 0–700°C with a heating rate of 10°C/min using Shimadzu thermogravimetric analyzer DTG-60H. Chemical reagents were purchased from Fluka and Sigma-Aldrich chemicals.

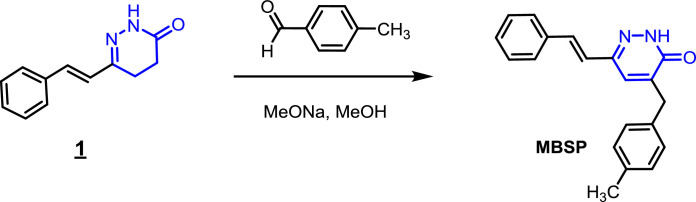

2.2. Synthesis

General procedure for the synthesis of (E)−4-(4-methylbenzyl)−6-styrylpyridazin-3(2H)-one (MBSP): To a solution containing 1 mmol of (E)−6-styryl-4,5-dihydropyridazin-3(2H)-one 1 and 1 mmol of 4-methylbenzaldehyde in 30 ml of ethanol, sodium methanoate (0.065 g, 1.2 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 6 h, and then stirred overnight at room temperature. The reaction was monitored by TLC. The reaction mixture was cooled, diluted with cold water and acidified with concentrated hydrochloric acid. The precipitate was filtered, washed with water, dried and recrystallized from ethanol. White single-crystals were obtained by slow evaporation at room temperature. Yield = 61%; m.p = 164–166°C; FT-IR (ν(cm−1)) : 3021 (NH), 2875–2958 (CH), 1652 (C O), 1589 (C N), 1547 (C C); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ (ppm): 12.98 (s, 1H, NH), 7.76 (s, 1H, H-Ar), 7.62 – 7.56 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 7.38 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.9 Hz, 2H, H-Ar), 7.34–7.24 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 7.23–7.17 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 7.10 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H, C CH and H4-pyrdz), 7.02 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H, CH C), 3.77 (s, 2H, CH2), 2.25 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ (ppm): 160.83, 143.78, 141.88, 136.01, 135.32, 135.09, 131.56, 128.94, 128.87, 128.76, 128.38, 127.18, 126.81, 126.55, 124.45, 34.62, 20.60. ESI-MS: m/z = 303.2 [M + H]+.

2.3. Computational details

2.3.1. DFT computation

The gas-phase structure of MBSP was optimized using density functional theory. The DFT calculations were performed by the hybrid B3LYP method, which is based on the idea of Becke and consider a mixture of the exact (HF) and DFT exchange utilizing the B3 functional, together with the LYP correlation functional [35], [36], [37]. In conjunction with the basis set def2-SVP, the B3LYP calculation was done [38]. After obtaining the converged geometry, the harmonic vibrational frequencies were calculated on the same theoretical level to confirm the number of imaginary frequency is zero for the stationary point. Based on the converged geometry of MBSP, the carbon, the hydrogen isotropic chemical shielding, and the vertical excitation energies to the lowest ten excited states were calculated on the B3LYP-GIAO, and the time-dependent CAM-B3LYP/def2-SVP, respectively [39,40].

Theoretically, the chemical shielding depends on the orientation of the molecule in the applied magnetic field. Therefore, the chemical shielding can be described by a matrix (σ) containing nine component Cartesian tensors.

| (1) |

Unfortunately, in conventional NMR experiments, the trace of the tensor can only be determined. Then the isotropic chemical shielding, σiso, is defined as

| (2) |

To do a more direct comparison between the B3LYP-calculated chemical shielding and the experimentally measured one, the chemical shielding of the commonly used internal reference, TMS was calculated on the same theoretical level.

Due to the poor description of the long-range exchange potential as −0.2 r −1 instead of the exact value −r −1, the time-dependent version of B3LYP functional failed to deal with the excitations for Rydberg states and charge transfer (CT) transitions [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]. Therefore, in 2004, Handy and his co-workers proposed a hybrid functional called CAM-B3LYP incorporating the long-range correction into the hybrid qualities of B3LYP. All calculations were done with the Gaussian 16 program [47]. The theoretical infrared and UV–Vis spectra of the title compounds were obtained by the Gauss Sum program 3.0 [48].

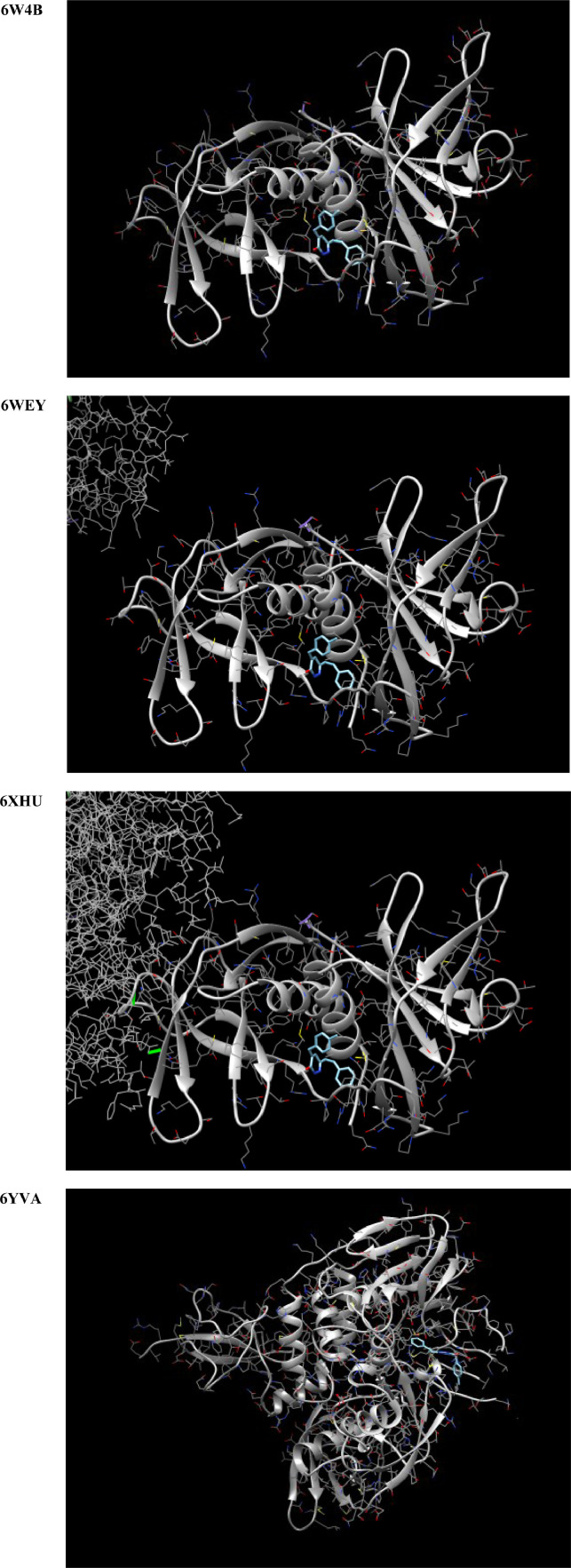

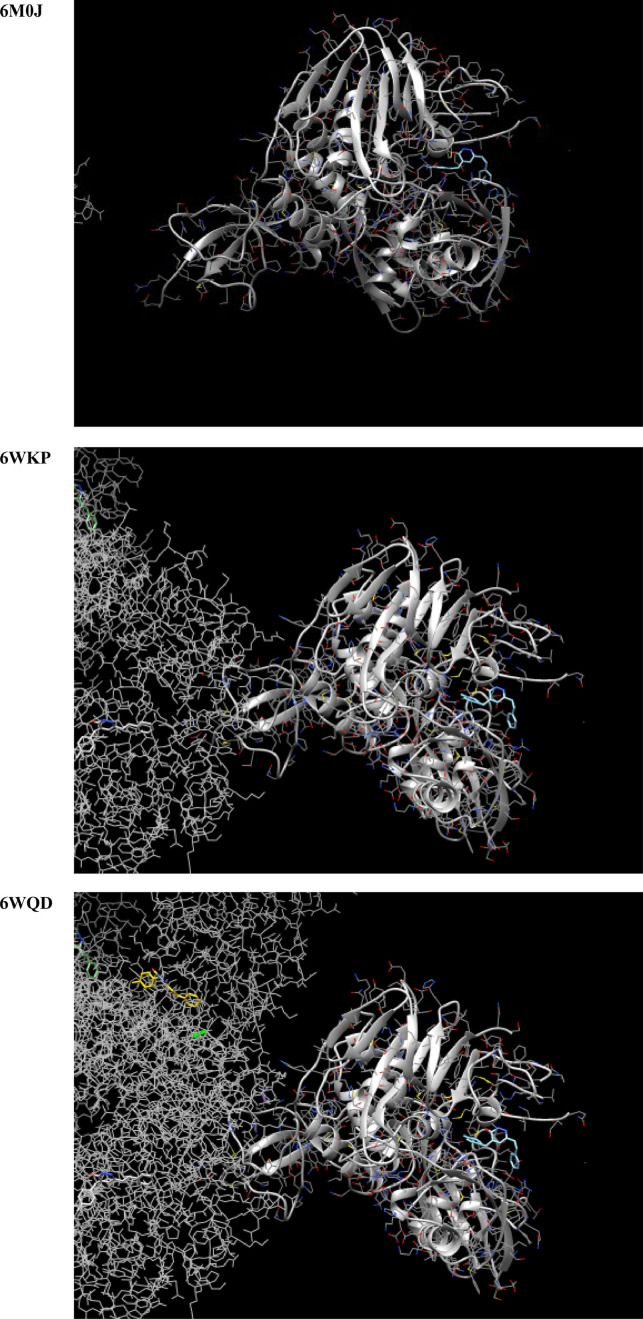

2.3.2. The Docking study

For generating the docking input file of the title compound, the DFT-B3LYP optimization output was converted to the sybyl .mol2 file by the OpenBabel program [49]. The nsp9 RNA binding protein (PDB ID: 6W4B), nsp3 macro X domain (PDB ID: 6WEY), 3c-like protease (PDB ID: 6XHU), panpin-ike protease (PDB ID: 6YVA), spike protein (PDB ID: 6M0J), nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (PDB ID: 6WKP), and the co-factor complex between nsp7 and the C-terminal domain of nsp8 (PDB ID: 6WQD) of SARS-CoV-2 were considered as the target for MBSP [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56]. The molecular docking to investigate whether a bound complex could be spontaneously formed between the chosen targets and MBSP was performed by the SwissDock [57,58]. The results of the molecular docking studies are opened and saved as images by the UCSF Chimera program [59].

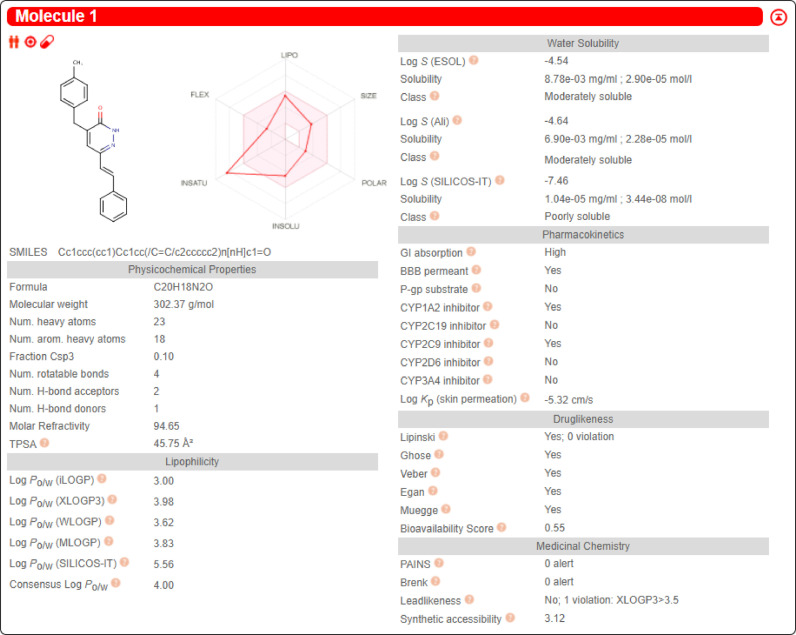

2.3.3. The ADME study

ADME is the abbreviation for "absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion" in pharmacokinetics and pharmacology and describes the distribution of drugs in organisms. ADME affects drug levels and the exposure of the drug to tissues and thus affects a compound's performance and pharmacological activity as a drug. In this study, the AMDE study is performed by the SwissADME [60].

2.4. X-ray crystallography studies

X-ray single-crystal diffraction for MBSP was collected at 296 K on a STOE IPDS II diffractometer equipped with an X-ray generator operating at 50 kV and 1 mA, using Mo-Kα radiation of wavelength 0.71073 Å. The hemisphere of data was processed using SAINT [61]. The 3D structure was solved by direct methods and refined by full-matrix least-squares method on F2 using the SHELXL program [62,63]. All the non-hydrogen atoms were revealed in the first difference Fourier map and were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. At the end of the refinement, the final difference Fourier map showed no peaks of chemical significance and the final residual was 0.0641. The molecular and packing diagrams were generated using DIAMOND [64].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Crystal structure of MBSP

A white colored stick-shaped crystal of dimensions 0.59 × 0.24 × 0.05 mm3 of MBSP was chosen for an X-ray diffraction study. The single-crystal X-ray diffraction data show that it crystallizes in a space group, P-1. The crystal belongs to the triclinic system with the following lattice parameters: a = 6.5290 (11) Å, b = 9.0411 (16) Å, c = 14.837 (3) Å and α = 105.930 (14) (°), β = 91.650 (15) (°), γ = 104.307 (14) (°), its unit cell volume is 811.7 (3) Å3. The details of the crystal data and structure refinement are given in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Crystallographic and refinement data for MBSP.

| CCDC Deposition Number | CCDC 1,985,486 |

|---|---|

| Chemical formula | C20H18N2O |

| Mr | 302.36 |

| Crystal system, space group | Triclinic, P-1 |

| Temperature (K) | 296 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 6.5290 (11), 9.0411 (16), 14.837 (3) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 105.930 (14), 91.650 (15), 104.307 (14) |

| V (Å3) | 811.7 (3) |

| Z | 2 |

| Radiation type | Mo Kα |

| µ (mm−1) | 0.08 |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.59 × 0.24 × 0.05 |

| Data collection | |

| Diffractometer | STOE IPDS 2 |

| Absorption correction | Integration (X-RED32, [65]) |

| Tmin, Tmax | 0.001, 0.012 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 5986, 2831, 1079 |

| Rint | 0.071 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.596 |

| Refinement | |

| R[F2 > 2σ(F2)], wR(F2), S | 0.081, 0.220, 0.89 |

| No. of reflections | 2831 |

| No. of parameters | 208 |

| H-atom treatment | H-atom parameters constrained |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.23, −0.19 |

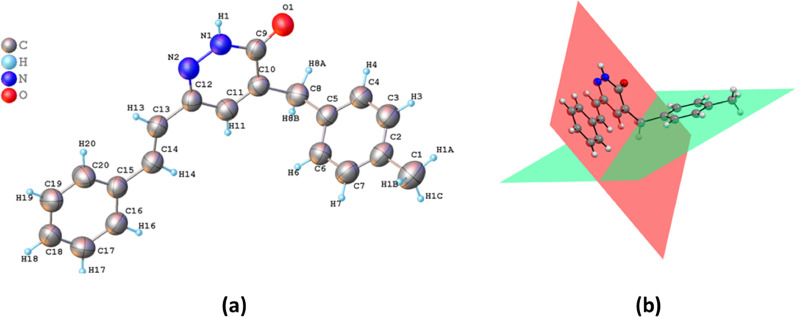

The molecular structure of the title compound composed of three rings. These rings are pyridazine, styryl, and 4-methylbenzyl, respectively. Pyridazine is connected to oxygen atom in the 3-position, 4-methylbenzyl in the 4-position of the ring, and styryl in the 6- position. The molecule is not planar as seen in Fig. 2 , the benzene ring C15/C20 is nearly planar to pyridazinone ring with a dihedral angle of 3.915 (329)°, the C2/C7 ring is nearly perpendicular to pyridazinone ring making a dihedral angle of 72.908 (121)°.

Fig. 2.

The molecular structure of MBSP, with atom labeling. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 40% probability level (a), visualizing of dihedral angles within the molecule (b).

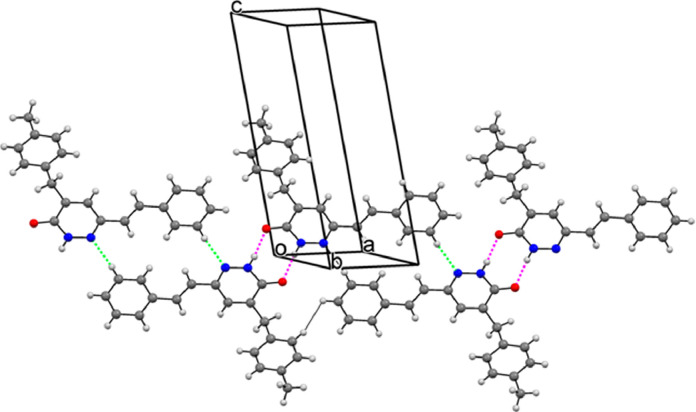

In the crystal, no significant C—H⋯π or π–π interactions are observed, hydrogen bonds were effective in the formation of the packing structure. The molecules are connected two-by-two through N—H⋯O hydrogen bonds, with an R2 2(8) graph-set motif and form inversion dimers. Pyridazinone rings are connected to the C15/C20 rings by C—H⋯N bonds getting R2 2(16) graph-set motif. Hydrogen bond geometries are given in Table 2 . In Fig. 3 , packing diagrams of the molecules are given with intermolecular H bonds. The N—H⋯O interactions are indicated by pink lines, C—H⋯N interactions are illustrated by green lines.

Table 2.

Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for MBSP.

| D—H•••A | D—H | H•••A | D•••A | D—H•••A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1—H1•••O1i | 0.86 | 2.01 | 2.863(5) | 174.9 |

| C19—H19•••N2ii | 0.93 | 2.55 | 3.470(7) | 170.5 |

| Symmetry code: (i) -x + 2, -y + 2, -z + 2; (ii) -x, -y + 1, -z + 2 | ||||

Fig. 3.

Packing diagrams with intermolecular interactions of the title compound.

3.2. The DFT-B3LYP results

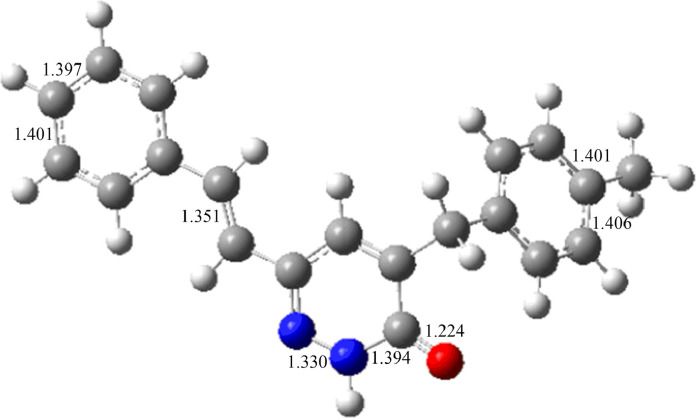

3.2.1. The brief comparison between the gas-phase geometry of MBSP optimizing by B3LYP and that of the crystallographic study

The converged geometry of MBSP is depicted in Fig. 4 . Structural parameters compared with the experimental crystal structure data are summarized in Table S1. For the pyridazinone ring, the bond lengths of C9-O1 = 1.238(5) Å (XRD), 1.224 (DFT), C12-N2 = 1.303(5) Å (XRD), 1.317 Å (DFT) and C10-C11 = 1.338(6) Å (XRD), 1.363 Å (DFT) confirm the double bond character. On the other hand, the experimental N—N bond length of the pyridazinone ring has a single bond character and its length in the isolated pyridazine ring is given as 1.33 Å [66]. In the present case, the N1-N2 bond length in the pyridazinone ring of the title compound was found to be 1.348(5) Å (XRD), 1.330 Å (DFT). The calculated C—C bond length in styryl ring varies from 1.393–1.411 Å which is larger than the experimental result 1.352–1.394 Å. Likewise, C—C bond length of the 4-methylbenzyl ring varies from 1.395–1.510 Å, these values are also larger than the experimental XRD values 1.238–1.504 Å. By the XRD, the bond length C5—C6 has the lowest value (1.238 (5) Å) and the C2-C1 bond length has the highest value (1.504 (8) Å) compared to other C—C bond lengths. However, the DFT study shows discrepancies exist for the C5-C6 bond length (1.401 Å) and the C1-C2 bond length (1.510 Å). For benzene rings, Maheswari et al. [67] reported the bond angles C4—C5—C6 = 120.0°, C3—C2—C7 = 118.6°, C13-C12-C17 = 117.1° and C14-C15-C16 = 120.4° In the present case, the bond angles in styryl and 4-methylbenzyl are C4-C5-C6 = 117.2° (XRD), 118.1° (DFT), C3-C2-C7 = 117.1° (XRD), 117.6° (DFT), and C16-C15-C20 = 116.3° (XRD), 117.8° (DFT).

Fig. 4.

The B3LYP-optimized geometries of the title compound (bond lengths in Å; nitrogen in blue, oxygen in red, carbon in gray, hydrogen in white).

According to our previous work [68] for pyridazinone ring, the bond angles N2-N1-C10 = 128.0°, O1-C10-N1 = 115.1°, N1-C10-C9 = 115.1°, and N2-C11-C12 = 121.3(3)°. In the present case, the corresponding bond angles in the title molecule are found as N2-N1-C9 = 116.4° (XRD), 129.2° (DFT), O1-C9-C10 = 124.3° (XRD), 126.3° (DFT), N1-C9-C10 = 114.5° (XRD), 113.0° (DFT) and N2-C12-C11 = 121.6° (XRD), 120.6° (DFT). For the pyridazinone ring, Daoui et al. [69] reported the torsion angles C10-N1-N2-C11 = −2.3(5)°, N2-N1-C10-O1 = −176.7(5)°, N2-N1-C10-C9 = 1.2(5)°, and N1-N2-C11-C12 = 1.9(5)° experimentally. For the title molecule, we have obtained −0.7(6), 179.3(4), 1.1(6), and −0.4(6)° experimentally and −0.45°, 179.86°, 0.32°, and 0.01° theoretically. The detailed comparison between the experimentally measured structure and the B3LYP calculated one were summarized in Table S1. As listed in Table S1, for the title compound MBSP, a difference between the experimentally measured structure and the DFT calculated one, which may be rationalized by the crystal packing [70], [71], [72].

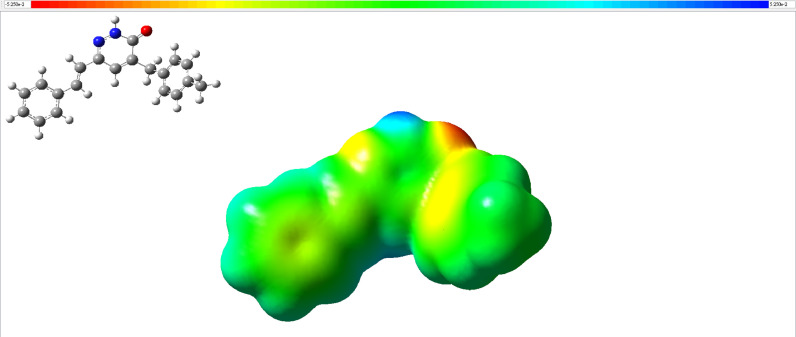

3.2.2. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP)

Fig. 5 shows the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface of the title compound constructed using B3LYP/def2-SVP. Red regions represent electron-rich regions (partial negative charge), and blue regions represent electron-poor regions (partial positive charge). On the other hand, fewer electrons containing regions are shown in yellow, while neutral regions (zero potential) are shown in green [73]. MEP maps contain important information as they show the chemical bonding and chemically active sites of the studied compound. The MEP of the title compound was calculated basing on the B3LYP-converged geometry for predicting reactive sites responsible for the electrophilic attack. As expected, the negative region is mainly on the oxygen atom bound to the carbon atom in the pyridazine ring. This indicates that the O atom in this negative region could act as the acceptor in hydrogen bonding, and the blue region represents a partial positive charge around the hydrogen bound to N2 nitrogen in the pyridazine ring. Therefore, the N2-H group could act as a donating group in the hydrogen bond. Thus, Fig. 5 confirms there should be N—H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding in the title compound, which agrees with the crystallographic results. The color code of these maps (studied with the DFT method) is in the range between −0.0525 a.u. (red) to 0.0525 a.u. (blue).

Fig. 5.

The molecular electrostatic potential for MBSP (the isodensity value= 0.0004).

3.2.3. The Mulliken atomic charges

For MBSP, the calculated Mulliken charges using DFT/B3LYP/def2-SVP were listed in Table 3 . The Mulliken atomic charge is highly effective in detecting nucleophilic or electrophilic attacks and regions sensitive to other molecular interactions. According to our DFT-B3LYP result, all hydrogen atoms are positively charged in MBSP. The hydrogen atoms bound to nitrogen have a high positive charge with a value of 0.1444. Moreover, the oxygen atom of the C O group has a high negative charge with the value −0.2266.

Table 3.

The B3LYP-calculated Mulliken atomic charges (in a.u.) of MBSP (The atomic designations can be seen in Fig. 2(a)).

| Atom | Charge | Atom | Charge | Atom | Charge | Atom | Charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | −0.2266 | H11 | −0.0240 | C6 | −0.0525 | C20 | −0.0863 |

| N2 | −0.0342 | C13 | 0.0507 | H6 | 0.0176 | H20 | 0.0444 |

| N1 | −0.0507 | H13 | −0.0165 | C4 | −0.0905 | C17 | −0.0000 |

| H1 | 0.1444 | C8 | 0.2204 | H4 | 0.0966 | H17 | 0.0208 |

| C9 | 0.1762 | H8A | 0.0193 | C3 | −0.0321 | C19 | −0.0224 |

| C15 | 0.1030 | H8B | −0.0123 | H3 | 0.0135 | H19 | 0.0207 |

| C12 | −0.0437 | C14 | 0.0056 | C18 | −0.0828 | C1 | 0.0632 |

| C5 | −0.0394 | H14 | −0.0270 | H18 | 0.0263 | H1A | −0.0244 |

| C2 | −0.0340 | C16 | −0.0306 | C7 | −0.0618 | H1B | −0.0109 |

| C10 | −0.1528 | H16 | −0.0257 | H7 | 0.0147 | H1C | −0.0304 |

| C11 | 0.0195 |

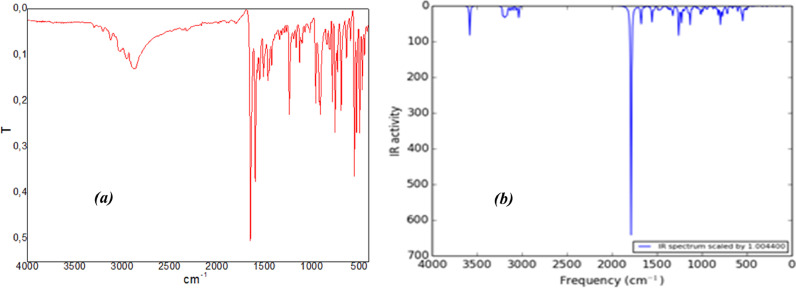

3.3. Infrared spectra

The experimental FT-IR spectrum of the title compound is summarized in Fig. 6 a. Furthermore, we performed a comparison between the DFT-calculated IR spectra and the experimental FT-IR spectra. For comparing easily, the theoretical IR spectrum is depicted in Fig. 6b. It is noteworthy that the theoretical IR spectra is drawn by scaling the normal mode frequencies with a scaling factor 1.0044 and choosing a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 10 cm−1 [74]. The comparison shows a clear blue shift in the theoretical spectra concerning the experimental one.

Fig. 6.

Experimental (a) and simulated (b) FT-IR spectra of the title compound.

The NH group is very characteristic, and their stretching vibrations are observed, in many cases, around 3200–3500 cm−1 [75]. This absorption, however, is highly influenced by the chemical environment, mainly when the NH group is involved in hydrogen bonding [76]. The ν(N—H) in the pyridazinone ring has been reported at 3337 cm−1 by Bahçeli et al. [77]. The corresponding signal in the title compound is observed by a sharp band of weak intensity at 3294 cm−1 in IR spectra and 3583 cm−1 in DFT. For substituted benzene, the C—H stretching vibrations give rise to bands in the region 3000 – 3100 cm−1 [75]. For MBSP, a series of infrared absorptions between 2905 and 3045 cm−1 were assigned as CH stretching modes of the benzene rings. The C—H in-plane deformation vibrations are observed in the region 1000 –1300 cm−1 and are usually of medium to weak intensity [75]. The bands due to C–H in-plane deformation vibration are observed as several bands in the region 1291 and 1017 cm−1 in IR. The CH out-of-plane deformations are observed between 600 and 900 cm−1 [75]. For mono-substituted benzenes, the bands are observed between 770–735 cm−1, and between 860 - 800 cm−1 for 1,4-substituted benzenes [75]. In the present work, the observed wavenumbers with weak intensity at 840, 810, 731, 634, and 593 cm−1 for MBSP in FTIR spectrum are identified as C—H out-of-plane deformation vibration.

The ν(C O) absorption is usually one of the most representative in an infrared spectrum and is also likely its most intense spectral feature. It appears in a wavenumber region relatively free of other vibrations (1600–1800 cm−1) [75]. The ν(C O) in pyridazinone ring has been reported at 1684 cm−1 by El-Mansy et al. [75], at 1674 cm−1 by Bahçeli et al. [76] and at 1634 cm−1 by Dede et al. [77]. In this study, ν(C O) vibration of the pyridazinone ring in the molecule originates one of the strongest bands of the experimental infrared spectrum, at 1650 cm−1 for the title compound. On the other hand, the C N stretching vibration in the pyridazinone ring is observed at 1599 cm−1 in IR. The DFT calculation gives this mode at 1587 cm−1. The C C ring stretching vibrations occur in the region 1430–1625 cm−1, the actual position of these modes depends on the nature of the substituents and the substitution pattern around the ring [75]. For MBSP, the infrared bands observed at 1552, 1509, 1460, and 1427 cm−1 are assigned as C C stretching vibrations of vinyl and benzene rings.

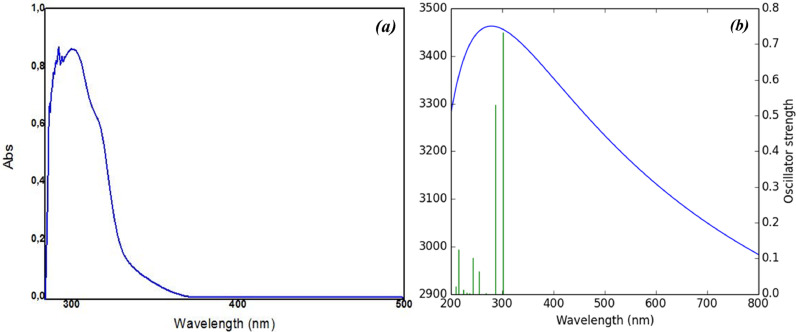

3.4. UV–vis spectra

The experimental UV–vis absorption spectrum of MBSP was recorded in methanol in the range 200–500 nm at 25°C and has shown in Fig. 7 . The absorption spectrum of MBSP is characterized by two bands; a longer wavelength band (LW) with a maximum around 331 nm. The LW band can be attributed to the π → π* transition within the heterocyclic moiety.

Fig. 7.

Experimental (a) and simulated (b) UV–vis spectra of the title compound.

To obtain the theoretical electronic absorption spectrum, the time-dependent version of the DFT CAM-B3LYP functional was used to calculate the vertical excitation energies of the ten excited states for the title compound. Additionally, the non-equilibrium solvation effect of methanol is taken into account by the IEFPCM model [78]. After the vertical excitation energy calculations, an FWHM of 100,000 cm−1 was used to draw the theoretical UV–Vis spectra of MBSP (Fig. 7). Also, the theoretical UV–Vis spectra are similar to the experimental one. Based on the TD-CAM-B3LYP results, the strongest transition for MBSP is S0/S1 occurred at 296 nm with an oscillator strength of 0.8405.

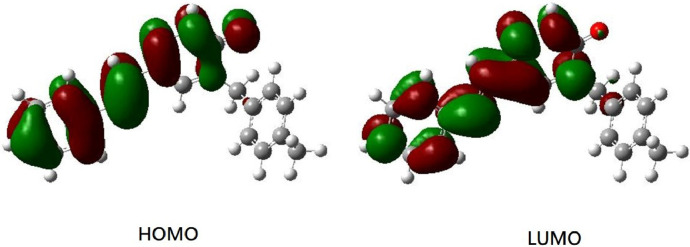

Furthermore, according to the TD-CAM-B3LYP result, the S0 → S1 electronic transition is mainly contributed by the HOMO → LUMO orbital transition. Therefore, the frontier orbitals of the title compound are depicted in Fig. 8 . As depicted in Fig. 8, the transition from the HOMO to LUMO of MBSP could be ascribed to a π → π* transition.

Fig. 8.

The frontier orbitals of MBSP (the isodensity value = 0.02).

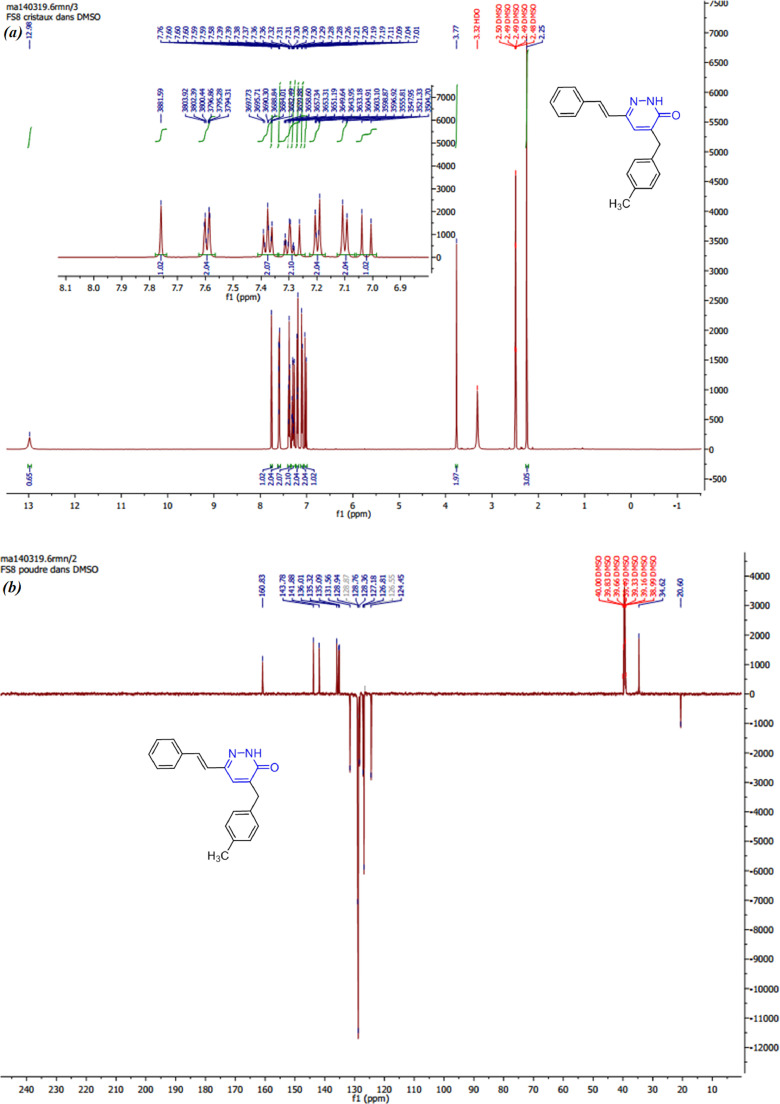

3.5. NMR studies

The experimental 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts of the title compound were obtained using TMS as an internal standard and DMSO‑d6 as solvent. The proton NMR spectrum of MBSP displayed two singlets at δ 2.25 and 3.77 ppm due to methyl (CH3) and methylene (-CH2-) protons, respectively, and two doublets at δ 7.02 and 7.10 ppm due to (-CH CH-) and pyridazinone (H-4) protons. The chemical shifts of the aromatic protons appeared as singlet at 7.76 ppm, doublet of doublets at 7.38 ppm, and three multiplets in the normal range between 7.62–7.56, 7.34–7.24, and 7.23–7.17 ppm. The chemical shift of the NH proton of pyridazinone appeared as a singlet at δ 12.98 ppm.

The carbon NMR spectrum showed the chemical shifts of C O at 160.83 ppm. The signals at 143.78, 141.88, and 136.01 ppm are clearly assigned for C12, C11, and C10 carbons of pyridazinone ring. The signals at 135.32 and 124.45 ppm are assigned for ethylene group chemical shifts (CH CH). The aromatic carbon chemical shifts of the title compound occurred in the range of 135.09–126.55 ppm. The signals at 34.62 and 20.60 ppm are assigned for methylene (CH2) and methyl (CH3) groups.

The B3LYP-GIAO method provides a powerful tool to check the signals of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra for a compound. Therefore, in this study, the gage-independent atomic orbital method was adopted on the B3LYP/def2-SVP theoretical level, and the resulting theoretical 1H and 13C isotropic chemical shieldings of MBSP were collected as Table 4 shows, which is in agreement with the aforementioned data of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra. Moreover, the experimental NMR spectra were depicted in Fig. 9 .

Table 4.

The 1H and 13C isotropic chemical shieldings (σisos) of MBSP (The atomic designations can be seen in Fig. 2(a)).

| Atoms | 1H chemical shielding (in ppm)a | Atoms | 13C chemical shielding (in ppm)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 8.67 | C9 | 154.18 |

| H4 | 7.94 | C10 | 143.46 |

| H20 | 7.65 | C12 | 139.97 |

| H11 | 7.29 | C5 | 135.31 |

| H19 | 7.14 | C2 | 134.53 |

| H17 | 7.11 | C15 | 134.46 |

| H18 | 6.95 | C14 | 129.02 |

| H3 | 6.94 | C16 | 128.72 |

| H16 | 6.90 | C4 | 127.67 |

| H6 | 6.87 | C3 | 126.75 |

| H13 | 6.83 | C7 | 126.27 |

| H7 | 6.79 | C19 | 125.78 |

| H14 | 6.55 | C17 | 125.78 |

| H8A | 4.16 | C18 | 125.37 |

| H8B | 2.76 | C6 | 124.96 |

| H1A | 2.34 | C13 | 123.53 |

| H1B | 2.27 | C11 | 121.93 |

| H1C | 1.67 | C20 | 120.88 |

| C8 | 38.66 | ||

| C1 | 21.70 |

The values were calculated by taking TMS as the internal reference.

Fig. 9.

The experimental (a) 1H and (b) 13C NMR spectra of MBSP.

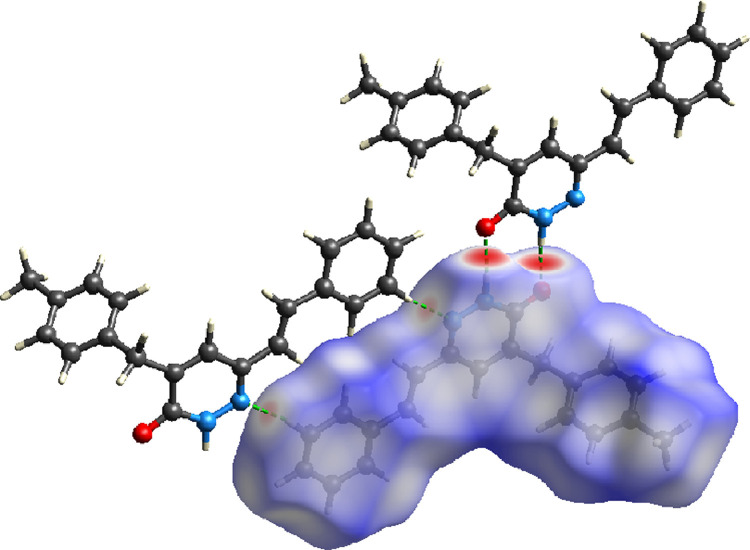

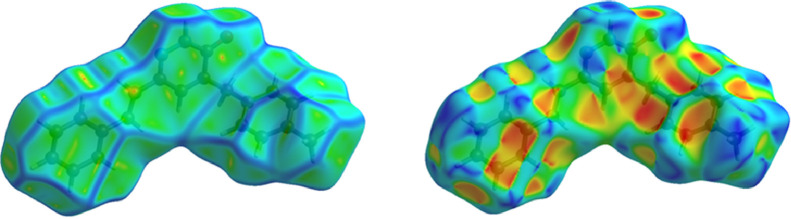

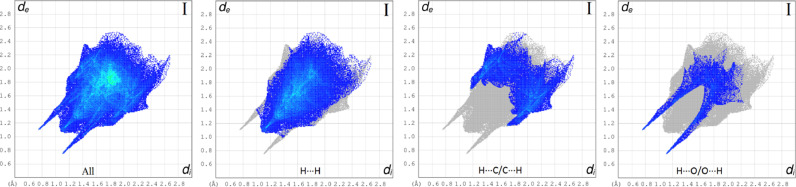

3.6. The Hirshfeld surface analysis

The Hirshfeld surface was analyzed to visualize and get an idea about the hydrogen bonds and intermolecular interactions. Hydrogen bonds and intermolecular interactions were revealed and investigated in the crystal structure of MBSP using the CrystalExplorer program [79]. Moreover, two-dimensional fingerprints and electrostatic potentials were shown using the same program. The molecular Hirshfeld surfaces; dnorm, curvedness, and shape index were carried out using a standard (high) surface resolution. The three-dimensional dnorm surfaces mapped over a fixed color scale of −0.584 (red) to 1.507 (blue). Atoms make intermolecular contacts smaller than the sum of their van der Waals radii, these contacts will be highlighted in red on the d norm surface. Longer contacts are blue, and contacts around the sum of van der Waals radii are white. The definition of d norm close contacts, which show up on the Hirshfeld surface as red spots, must occur in pairs of identical size, either on another region of the same Hirshfeld surface, or on a neighbouring one. The 3D dnorm surface of the title compound is illustrated in Fig. 10 . The red spots symbolize N—H⋯O contacts for MBSP and negative dnorm values on the surface and pale-red spots symbolize N—H⋯C interactions as seen in Fig. 10. In Fig. 11 , the curvedness and shape index surfaces of the molecule are given. The shape index surface indicates whether π- π interactions have occurred with adjacent red and blue triangles. Looking at the shape index map of the molecule, there are no obvious triangles. This is evidence that no significant π- π interactions were observed in the molecule.

Fig. 10.

dnorm mapped on Hirshfeld surfaces for visualizing the interactions of the title compound.

Fig. 11.

Curvedness and shape indexes are shown for MBSP.

All interactions that contribute to the Hirshfeld surface and interactions that contribute more than 4% are indicated by two-dimensional fingerprint plots in Fig. 12 . The largest interaction is H∙∙∙H contributing 54.0% to the overall crystal packing. H•••O/O•••H contacts make 9.3% contribution to the Hirshfeld surface. The contacts are represented by a pair of sharp spikes in the region de + di ~ 1.85 Å in the fingerprint plot. H•••O/O•••H interactions arise from the intermolecular N—H•••O hydrogen bonding (Table 2) and H•••O/O•••H contacts. The contributions of the other contact to the Hirshfeld surface is C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C (25.0%), N∙∙∙C/C∙∙∙N (3.7%), N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N (2.9%), N∙∙∙N (0.9%).

Fig. 12.

Fingerprint plots of the whole molecules and the most effective interactions.

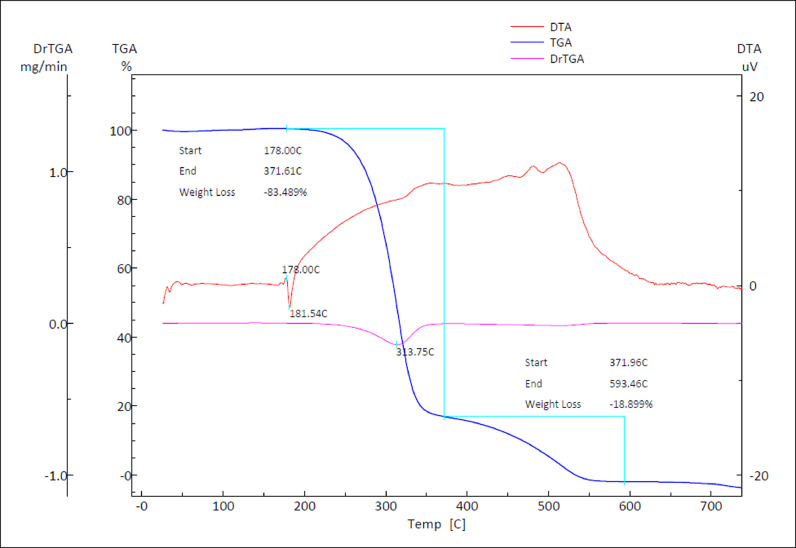

3.7. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential thermal analysis (DTA)

To study the behavior of the sample material against temperature, differential thermal analysis (DTA) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the title compound in the temperature range from 50 to 700°C with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1, were studied. Fig. 13 shows the TGA, DrTGA, and DTA curves of MBSP. Differential thermal analysis (DTA) is a method in which the temperature difference between the sample and the inert reference substance is measured as the function of the applied temperature. The TG analysis showed that the title compound is stable up to 178.00°C with no phase transition and decomposes at higher temperatures in two steps. The first decomposition with the major weight loss of the title compound has initiated at about 178.00°C and has been completed at 371.61°C where 83.49% weight loss has been observed. The weight loss occurs immediately after melting. In the DTA curve, the endothermic peak at 181.54°C which may be due to the melting point of the substance, and second sharp peak around 372°C indicates the major decomposition of the substance. The substance undergoes a total decomposition in the temperature range of 371.96 - 593.42°C, with 18.89% weight loss.

Fig. 13.

TGA, DTA, and DrTGA curves of the title compound.

3.8. The molecular docking study

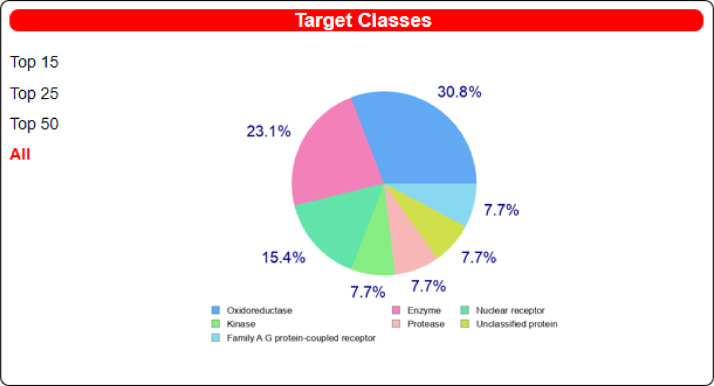

The results of the molecular docking studies are summarized in Fig. 14 and Table 5 . Accordingly, although the nsp9 RNA binding protein and spike protein of SARS-COV-2 are not possible targets for MBSP, the nsp3 macro X domain, 3c-like protease, panpin-ike protease, nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (PDB ID: 6WKP), and the co-factor complex between nsp7 and the C-terminal domain of nsp8 (PDB ID: 6WQD) of SARS-CoV-2 should be possible targets for MBSP. The title compound should be a candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Furthermore, the interference of other possible targets of MBSP is also considered in this study. After converting the DFT optimization output file into the .smiles file, the possible targets of MBSP are predicted by the SwissTargetPrediction program [80]. The obtained docking results of the title ligand and targets were presented in Fig. 15 . As depicted in Fig. 15, the treatment of COVID-19 with MBSP might be interference by an oxidoreductase with a probability of 30.8%.

Fig. 14.

The results of the docking studies of MBSP concerning the chosen targets.

Table 5.

The estimated ΔG (in kcal/mol) of MBSP concerning the chosen targets.

| Target | 6W4B | 6WEY | 6XHU | 6YVA | 6M0J | 6WKP | 6WQD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG (kcal/mol) | 3.35 | −6.40 | −6.21 | −5.38 | 28.70 | −5.62 | −5.71 |

Fig. 15.

The possible targets of MBSP.

3.9. The ADME study

The result of the SwissADME is shown in Fig. 16 . According to the docking and ADME results, MBSP should be a potential therapeutic for COVID-19. Thus, further in-vitro and in-vivo tests should be performed to confirm these results.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route of (MBSP).

Fig. 16.

The SwissADME result.

4. Conclusion

In summary, novel pyridazin-3(2H)-one derivative, namely, (E)−4-(4-methylbenzyl)−6-styrylpyridazin-3(2H)-one (MBSP) has been synthesized and characterized by FT-IR, UV–vis, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, ESI-MS, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction study. Furthermore, the theoretical IR and UV–Vis of the studied compound were also obtained to compare with the experimental ones. The molecular geometry and electronic characters of the target compound were explored with the aid of DFT calculations. The DFT result showed that the gas-phase geometry should slightly differ from the solid-phase one. The Hirshfeld surface analysis and fingerprint plots give the nature of intramolecular interactions and percentage contribution from the individual contact. The thermal behavior and stability of the compound were analyzed by using TGA and DTA techniques which revealed that the title compound is thermostable up to its melting point. Finally, docking and ADME results displayed that MBSP possessed a good binding profile against chosen target proteins. Also, a further in-vivo or in-vitro test about MBSP for the treatment of COVID-19 should be performed.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Fouad El Kalai: Conceptualization, Methodology. Emine Berrin Çınar: Conceptualization, Methodology. Chin-Hung Lai: Software, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Said Daoui: . Tarik Chelfi: Formal analysis. Mustapha Allali: Investigation. Necmi Dege: Validation. Khalid Karrouchi: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Noureddine Benchat: Supervision, Project administration.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Mohammed I University of Oujda and Ondokuz Mayıs University (under project No. PYOFEN.1906.19.001). We also thank the National Center for High-performance Computing (Taiwan) for providing computing time to do the DFT calculations. Special thanks are also due to the reviewers and the editor for their helpful suggestions and comments.

References

- 1.Lee S.G., Kim J.J., Kim H.K., Kweon D.H., Kang Y.J., Cho S.D., Kim S.K., Yoon Y.J. Recent progress in pyridazin-3 (2H)-ones chemistry. Curr. Org. Chem. 2004;8:1463–1480. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giustiniano M., Mercalli V., Amato J., Novellino E., Tron G.C. Exploiting the electrophilic and nucleophilic dual role of nitrile imines: one-Pot, Three-component synthesis of furo [2, 3-d] pyridazin-4 (5 H)-ones. Org. Lett. 2015;17:3964–3967. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suchand B., Satyanarayana G. Palladium-Catalyzed Acylation Reactions: a One-Pot Diversified Synthesis of Phthalazines, Phthalazinones and Benzoxazinones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018;19:2233–2246. [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Ghaffar N.A., Mohamed M.K., Kadah M.S., Radwan A.M., Said G.H., Abd S.N. Synthesis and anti-tumor activities of some new pyridazinones containing the 2-phenyl-1H-indolyl moiety. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2011;3:248–259. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siddiqui A.A., Mishra R., Shaharyar M., Husain A., Rashid M., Pal P. Triazole incorporated pyridazinones as a new class of antihypertensive agents: design, synthesis and in vivo screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:1023–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhtar W., Shaquiquzzaman M., Akhter M., Verma G., Khan M.F., Alam M.M. The therapeutic journey of pyridazinone. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;123:256–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livermore D.G.H., Bethell R.C., Cammack N., Hancock A.P., Hann M.M., Green D.V.S., Lamont R.B., Noble S.A., Orr D.C. Synthesis and anti-HIV-1 activity of a series of imidazo [1, 5-b] pyridazines. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:3784–3794. doi: 10.1021/jm00076a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mogilski S., Kubacka M., Redzicka A., Kazek G., Dudek M., Malinka W., Filipek B. Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and smooth muscle relaxant activities of the pyrrolo [3, 4-d] pyridazinone derivatives: possible mechanisms of action. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2015;133:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boukharsa Y., Meddah B., Tiendrebeogo R.Y., Ibrahimi A., Taoufik J., Cherrah Y., Faouzi M.E.A. Synthesis and antidepressant activity of 5-(benzo [b] furan-2-ylmethyl)-6-methylpyridazin-3 (2H)-one derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2016;25(3):494–500. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partap S., Akhtar M.J., Yar M.S., Hassan M.Z., Siddiqui A.A. Pyridazinone hybrids: design, synthesis and evaluation as potential anticonvulsant agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;77:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costas T., Costas-Lago M.C., Vila N., Besada P., Cano E., Terán C. New platelet aggregation inhibitors based on pyridazinone moiety. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;94:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akahane A., Katayama H., Mitsunaga T., Kato T., Kinoshita T., Kita Y., Shiokawa Y. Discovery of 6-Oxo-3-(2-phenylpyrazolo [1, 5-a] pyridin-3-yl)-1 (6 H)-pyridazinebutanoic Acid (FK 838): a Novel Non-Xanthine Adenosine A1 Receptor Antagonist with Potent Diuretic Activity. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:779–783. doi: 10.1021/jm980671w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sotelo E., Coelho A., Ravina E. Pyridazines. Part 34: retro-ene-assisted palladium-catalyzed synthesis of 4, 5-disubstituted-3 (2H)-pyridazinones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:4459–4462. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmoodi N.O., Safari N., Sharifzadeh B. One-pot synthesis of novel 2-(thiazol-2-yl)-4, 5-dihydropyridazin-3 (2 H)-one derivatives catalyzed by activated KSF. Synth. Commun. 2014;44:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takaya M., Sato M. Studies on pyridazinone derivatives. XVI. Analgesic-antiinflammatory activities of 3 (2H)-pyridazinone derivatives. Yakugaku zasshi. 1994;114:94–110. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.114.2_94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abouzid K., Hakeem M.A., Khalil O., Maklad Y. Pyridazinone derivatives: design, synthesis, and in vitro vasorelaxant activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16(1):382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Archan S., Toller W. Levosimendan: current status and future prospects. Curr. Opin. Anesthesio. 2008;21:78–84. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3282f357a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson D.W., Jones N.D., Krushinski J.H., Pollock G.D., Swartzendruber J.K., Hayes J.S. Molecular structure of the dihydropyridazinone cardiotonic 1, 3-dihydro-3, 3-dimethyl-5-(1, 4, 5, 6-tetrahydro-6-oxo-3-pyridazinyl)-2H-indol-2-one, a potent inhibitor of cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase. J. Med. Chem. 1987;30:623–627. doi: 10.1021/jm00387a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Combs D.W., Rampulla M.S., Bell S.C., Klaubert D.H., Tobia A.J., Falotico R., Moore J.B. 6-Benzoxazinylpyridazin-3-ones: potent, long-acting positive inotrope and peripheral vasodilator agents. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:380–386. doi: 10.1021/jm00163a061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chetouani A., Aouniti A., Hammouti B., Benchat N., Benhadda T., Kertit S. Corrosion inhibitors for iron in hydrochloride acid solution by newly synthesised pyridazine derivatives. Corrosion Sci. 2003;45:1675–1684. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalai F.El, Chelfi T., Benchat N., Hacht B., Bouklah M., Elaatiaoui A., Almalki F. New organic extractant based on pyridazinone scaffold compounds: liquid-liquid extraction study and DFT calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1191:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arrue L., Rey M., Rubilar-Hernandez C., Correa S., Molins E., Norambuena L., Schott E. Synthesis, characterization, spectroscopic properties and DFT study of a new pyridazinone family. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1148:162–169. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacomini A.P., Silva M.J., Silva R.G., Gonçalves D.S., Volpato H., Basso E.A., Rosa F.A. Synthesis and evaluation against Leishmania amazonensis of novel pyrazolo [3, 4-d] pyridazinone-N-acylhydrazone-(bi) thiophene hybrids. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;124:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar R., Singh P., Gaurav A., Yadav P., Khanna R.S., Tewari A.K. Synthesis of Diphenyl Pyridazinone-based flexible system for conformational studies through weak noncovalent interactions: application in DNA binding. J. Chem. Sci. 2016;128:555–564. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Betti L., Corelli F., Floridi M., Giannaccini G., Maccari L., Manetti F., Botta M. α1-Adrenoceptor Antagonists. 6. Structural Optimization of Pyridazinone− Arylpiperazines. Study of the Influence on Affinity and Selectivity of Cyclic Substituents at the Pyridazinone Ring and Alkoxy Groups at the Arylpiperazine Moiety. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3555–3558. doi: 10.1021/jm0307842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chakib I., Bakri Y.El, Lai C.H., Benbacer L., Zerzouf A., Essassi E.M., Mague J.T. Synthesis, anticancer evaluation in vitro, DFT, Hirshfeld surface analysis of some new 4-(1, 3-benzothiazol-2-yl)-3-methyl-1-phenyl-4, 5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-5-one derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1198 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tighadouini S., Benabbes R., Tillard M., Eddike D., Haboubi K., Karrouchi K., Radi S. Synthesis, crystal structure, DFT studies and biological activity of (Z)-3-(3-bromophenyl)-1-(1, 5-dimethyl-1 H-pyrazol-3-yl)-3-hydroxyprop-2-en-1-one. Chem. Cent. J. 2018;12(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s13065-018-0492-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karrouchi K., Yousfi E., Sebbar N., Ramli Y., Taoufik J., Ouzidan Y., Mabkhot Y.N., Ghabbour H.A., Radi S. New Pyrazole-Hydrazone Derivatives: x-ray Analysis, Molecular Structure Investigation via Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Their High In-Situ Catecholase Activity. Inter. J Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2215. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pillai R.R., Karrouchi K., Fettach S., Armaković S., Armaković S.J., Brik Y., Taoufik J., Radi S., Faouzi M.E.A., Ansar M.H. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, reactive properties by DFT calculations, molecular dynamics simulations and biological evaluation of Schiff bases tethered 1, 2, 4-triazole and pyrazole rings. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1177:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouzian Y., Karrouchi K., Sert Y., Lai C.H., Mahi L., Ahabchane N.H., Talbaoui A., Mague J.T., Essassi E.M. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, crystal structure, DFT, molecular docking and in vitro antibacterial potential of novel quinoline derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1209 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalai F.El, Baydere C., Daoui S., Saddik R., Dege N., Karrouchi K., Benchat N. Crystal structure and Hirshfeld surface analysis of ethyl 2-[5-(3-chlorobenzyl)-6-oxo-3-phenyl-1, 6-dihydropyridazin-1-yl] acetate. Acta Cryst. 2019;E75:892–895. doi: 10.1107/S2056989019007424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daoui S., Baydere C., Kalai F.El, Saddik R., Dege N., Karrouchi K., Benchat N. Crystal structure and Hirshfeld surface analysis of (E)-6-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxystyryl)-4, 5-dihydropyridazin-3 (2H)-one. Acta Cryst. 2019;E75:1734–1737. doi: 10.1107/S2056989019014130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daoui S., Baydere C., Kalai F.El, Mahi L., Saddik R., Dege N., Karrouchi K., Benchat N. Crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis and DFT studies of 2-[5-(4-methylbenzyl)-6-oxo-3-phenyl-1, 6-dihydropyridazin-1-yl] acetic acid. Acta Cryst. 2019;E75:1925–1929. doi: 10.1107/S2056989019015317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hopkins C. Nose and Throat surgery body of United Kingdom; 28 March 2020. Loss of Sense of Smell As Marker of COVID-19 infection. Ear. Retrieved. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becke A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee C., Yang W., Parr R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlationenergy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miehlich B., Savin A., Stoll H., Preuss H. Results obtained with the correlation-energy density functionals of Becke and lee, Yang and Parr. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989;157:200–206. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weigend F., Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005;7:3297–3305. doi: 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.London F. The quantic theory of inter-atomic currents in aromatic combinations. J. Phys. Radium. 1937;8:397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanai T., Tew D., Handy N. A new hybrid exchange-correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP) Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004;393:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Casida M.E. In: Chong D.P., editor. Vol. 1. World Scientific; Singapore: 1995. pp. 155–192. (Recent Advances in Density Functional Methods). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bauernschmitt R., Ahlrichs R. Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time-dependent density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996;256:454–464. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tozer D.J., Handy N.C. Improving virtual Kohn-Sham orbitals and eigenvalues: application to excitation energies and static polarizabilities. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;109:10180–10189. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tozer D.J., Amos R.D., Handy N.C., Roos B.O., Serrano-Andres L. Does density functional theory contribute to the understanding of excited states of unsaturated organic compounds? Mol. Phys. 1999;97:859–868. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dreuw A., Weisman J.L., Head-Gordon M. Long-range charge-transfer excited states in time-dependent density functional theory require non-local exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:2943–2946. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernasconi L., Sprik M., Hutter J. Time-dependent density functional theory study of charge-transfer and intramolecular electronic excitations in acetonewater systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:12417–12431. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Li X., Caricato M., Marenich A.V., Bloino J., Janesko B.G., Gomperts R., Mennucci B., Hratchian H.P., Ortiz J.V., Izmaylov A.F., Sonnenberg J.L., Williams-Young D., Ding F., Lipparini F., Egidi F., Goings J., Peng B., Petrone A., Henderson T., Ranasinghe D., Zakrzewski V.G., Gao J., Rega N., Zheng G., Liang W., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Throssell K., Montgomery J.A., Peralta J.E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M.J., Heyd J.J., Brothers E.N., Kudin K.N., Staroverov V.N., Keith T.A., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A.P., Burant J.C., Iyengar S.S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Millam J.M., Klene M., Adamo C., Cammi R., Ochterski J.W., Martin R.L., Morokuma K., Farkas O., Foresman J.B., Fox D.J. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2016. Gaussian 16, Revision A.03. [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'boyle N.M., Tenderholt A.L., Langner K.M. cclib, A library for package-independent computational chemistry algorithms. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:839–845. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Boyle N.M., Banck M., James C.A., Morley C., Vandermeersch T., Hutchison G.R. Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.K. Tan, Y. Kim, R. Jedrzejczak, N. Maltseva, M. Endres, K. Michalska, A. Joachimiak, The Crystal Structure of Nsp9 RNA Binding Protein of SARS CoV-2. (2020) DOI: 10.2210/pdb6W4B/pdb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Frick D.N., Virdi R.S., Vuksanovic N., Dahal N., Silvaggi N.R. Molecular Basis for ADP-Ribose Binding to the Mac1 Domain of SARS-CoV-2 nsp3. Biochemistry. 2020;59:2608–2615. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D.W. Kneller, L. Coates, A. Kovalevsky, Room Temperature X-ray Crystallography Reveals Oxidation and Reactivity of Cysteine Residues in SARS-CoV-2 3CL Mpro: Insights for Enzyme Mechanism and Drug Design. (2020) DOI: 10.2210/pdb6xhu/pdb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Shin D., Mukherjee R., Grewe D., Bojkova D., Baek K., Bhattacharya A., Schulz L., Widera M., Mehdipour A.R., Tascher G., Geurink P.P., Wilhelm A., van der Heden van Noort G.J., Ovaa H., Müller S., Knobeloch K.-.P., Rajalingam K., Schulman B.A., Cinatl J., Hummer G., Ciesek S., Dikic I. Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang X. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.C. Chang, K. Michalska, R. Jedrzejczak, N. Maltseva, M. Endres, A. Godzik, Y. Kim, A. Joachimiak, Crystal Structure of RNA-binding Domain of Nucleocapsid Phosphoprotein from SARS CoV-2, Monoclinic Crystal Form. (2020) DOI: 10.2210/pdb6wkp/pdb.

- 56.Y. Kim, M. Wilamowski, R. Jedrzejczak, N. Maltseva, M. Endres, A. Godzik, K. Michalska, A. Joachimiak, The 1.95 A Crystal Structure of the Co-factor Complex of NSP7 and the C-terminal Domain of NSP8 from SARS-CoV-2. (2020) DOI: 10.2210/pdb6wqd/pdb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Grosdidier A., Zoete V., Michielin O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W270–W277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr366. Web Server issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grosdidier A., Zoete V., Michielin O. Fast docking using the CHARMM force field with EADock DSS. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:2149–2159. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, druglikeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheldrick G.M. SHELXT. Acta Cryst. A. 2015;71:3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bruker . Bruker AXS, Inc.; Madison, WI: 2016. APEX3, SAINT, SADABS & SHELXTL. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sheldrick G.M. SHELXL-2014/7. Acta Cryst. 2015;C71:3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brandenburg K., Putz H. Crystal Impact GbR; Bonn, Germany: 2012. DIAMOND. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stoe & Cie . Stoe & Cie GmbH; Darmstadt, Germany: 2002. X-AREA and X-RED32. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dilek N., Güneş B., Şahin E., Ide S., Ünlü S. 6-[3-Phenyl-5-(trifluoromethyl) pyrazol-1-yl] pyridazin-3 (2H)-one. Acta Cryst. E. 2006;62:446–448. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maheswari R., Manjula J. Vibrational spectroscopic analysis and molecular docking studies of (E)-4-methoxy-N′-(4-methylbenzylidene) benzohydrazide by DFT. J. Mol. Struct. 2016;1115:144–155. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daoui S., Cinar E.B., Kalai F.El, Saddik R., Karrouchi K., Benchat N., Dege N. Crystal structure and Hirshfeld surface analysis of 4-(4-methylbenzyl)-6-phenylpyridazin-3 (2H)-one. Acta Cryst. 2019;E75:1352–1356. doi: 10.1107/S2056989019011551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reichman S., Schreiner F. Gas-phase structure of XeF2. J. Chem. Phys. 1969;51:2355–2358. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liao M.S., Zhang Q.E. Chemical bonding in XeF2, XeF4, KrF2, KrF4, RnF2, XeCl2, and XeBr2: from the gas phase to the solid state. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:10647–10654. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lai C.-.H. A comparison of diamino- and diamidocarbenes toward dimerization. J. Mol. Model. 2013;19:4387–4394. doi: 10.1007/s00894-013-1957-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Drissi M., Chouaih A., Megrouss Y., Hamzaoui F. Electron charge density distribution from x-ray diffraction study of the 4-methoxybenzenecarbothioamide compound. J. Crystallogr. 2013;2013:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kesharwani M.K., Brauer B., Martin J.M.L. Frequency and Zero-Point Vibrational Energy Scale Factors for Double-Hybrid Density Functionals (and Other Selected Methods): can Anharmonic Force Fields Be Avoided? J. Phys. Chem. A. 2015;119:1701–1714. doi: 10.1021/jp508422u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mayo D.W., Miller F.A., Hannah R.W. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. Course Notes On the Interpretation of Infrared and Raman spectra. [Google Scholar]

- 75.El-Mansy M.A.M., El-Bana M.S., Fouad S.S. On the spectroscopic analyses of 3-Hydroxy-1-Phenyl-Pyridazin-6 (2H) one (HPHP): a comparative experimental and computational study. Spectrochim. Acta A. 2017;176:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2016.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bahçeli S., Gökce H. A Study on Spectroscopic and Quantum Chemical Calculations of Levosimendan. Indian. J. Pure. Ap. Phy. 2014;52:224–235. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dede B., Avcı D., Bahçeli S. Study on the 4-ethoxy-2-methyl-5-(4-morpholinyl)-3 (2H)-pyridazinone using FT-IR, 1H and 13C NMR, UV-vis spectroscopy, and DFT/HSEH1PBE method. Can. J. Phys. 2018;96(9):1042–1052. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sarıkaya E.K., Bahçeli S., Varkal D., Dereli Ö. FT-IR, micro-Raman and UV–vis spectroscopic and quantum chemical calculation studies on the 6-chloro-4-hydroxy-3-phenyl pyridazine compound. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1141:44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turner M.J., McKinnon J.J., Wolff S.K., Grimwood D.J., Spackman P.R., Jayatilaka D., Spackman M.A. University of Western Australia; 2017. CrystalExplorer 17. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W357–W364. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]