Abstract

Objective

There is limited evidence regarding the association between dietary acid load and muscle strength. Thus, in this study, we investigated the association between dietary acid–base load indices and muscle strength among Iranian adults.

Results

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 270 Iranian adults, aged 18–70 year. Dietary acid load indexes, were calculated by using a validated 168-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Muscle strength was measured by a digital handgrip dynamometer.

There was a significant increase in mean muscle strength of left-hand (MSL), muscle strength of right-hand (MSR) and the mean of the MSL and MSR (MMS) across tertiles of Potential Renal Acid Load (PRAL), Net Endogenous Acid Production (NEAP), and Dietary Acid Load (DAL). Significant linear relationships between PRAL and; MSL (β = 0.24, p < 0.001), MSR (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) and MMS (β = 0.24, p < 0.001), between NEAP and MSL (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), MSR (β = 0.19, p = 0.002), and MMS (β = 0.20, p = 0.001) and between DAL and MSL (β = 0.25, p < 0.001), MSR (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) and MMS (β = 0.24, p < 0.001), were attenuated after controlling for potential confounders. However, the nonlinear relationship between dietary acid load indicators and muscle strength were significant (p < 0.001 for all).

Keywords: Dietary acid load, Muscle strength, Muscle mass, Acidogenic diet, Alkalogenic diet

Introduction

Muscle strength is defined as the ability to produce maximum force [1]. Muscle strength and muscle mass decline with aging; Comparatively, the decline is faster for muscle strength, and can lead to difficulties in daily activities, weakness, disability, decrease in quality of life, and early mortality [2]. Several factors, such as lifestyle, diet quality and dietary patterns [3], low protein intake [4], obesity [5] and physical activity [6] may elicit negative effects on muscle strength. Many nutritional studies that have investigated the effect of single macro- and micro-nutrients on skeletal muscle function have reported equivocal findings [7, 8]. For example, Daly et al. found that a diet enriched in protein from lean red meat (~ 1.3 gr/kg/day) can improve muscle strength in woman aged 60–90 year [7]; whilst a meta-analysis showed that supplemental protein intake improves muscle mass and strength just in resistance-trained individuals but not in trained ones [8].

Generally, foods rich in animal protein, such as meat, cheese, eggs, and grains increase the production of acid in the body because they are involved in the formation of hydrogen sulfate that arises from sulfur-containing amino acids, and phosphoric acid from phospholipids. In contrast, foods rich in plant protein and potassium, such as fruits and vegetables, increase alkaline products and are known as alkalogenic foods [9, 10]. Welch et al. reported a positive significant relationship between fat-free mass and an alkalogenic diet rich in fruits and vegetables [11]. Some formulas have been used to assess acid load from diet; for example, potential renal acid load (PRAL), net endogenous acid production (NEAP) [12], and dietary acid load (DAL) [13, 14]. PRAL and DAL scores are better predictors of dietary acid load, because NEAP is calculated from the ratio of protein and potassium, but PRAL and DAL formulas include calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium in addition to protein and potassium [9, 13].

To the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the link between dietary acid load and muscle strength. Therefore, our study aimed to investigate the relationship between dietary acid load and muscle strength among adults living in Iran.

Main text

Materials and methods

Study population

In this cross-sectional study, we enrolled 270 subjects who were living in Tehran, Iran. Recruitment was conducted via advertisement. Inclusion criteria included; age range of 18–70 year and were interested in participating in the study. Exclusion criteria included: (1) pregnant and lactating women, (2) any regular treatment with special supplements or drugs, (3) presence of clinical and subclinical diseases, and (4) inability to conduct tests. Trained research assistants collected information about health conditions and medical history. Information on physical activity, demographic data, also, blood pressure data, and anthropometric data were recorded.

Anthropometric measures and body composition

Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a wall-mounted stadiometer (Seca, Germany), and weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital scale (Seca 808, Germany), with both measurements taken with participants unshod and in light clothing. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Waist circumference (WC) was measured, to the nearest 0.1 cm, midway between the inferior border of the rib cage and the superior aspect of the iliac crest, using a non-elastic tape. A body composition analyzer (In Body Sweden, 2017) was used for the measurement of body composition [15].

Blood pressure assessment

Blood pressure was measured using a digital sphygmomanometer (BC 08, Beurer, Germany). The participant sat for 10–15 min before two measurements were taken. The means for systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were used in subsequent analyses.

Physical activity

To assess physical activity, we used the short form of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [16]. Data on moderate and vigorous activity, and walking for at least 10 min/day, during the previous 7 days were recorded according to the IPAQ criteria. Duration and frequency of the days of activity were multiplied by the activity's metabolic equivalent task value for calculating the activity. Total physical activity per week was used to define groups of low, moderate, and high, and weekly metabolic equivalent (METS)-Minutes were computed.

Dietary assessment

Dietary intake was calculated using a validated 168-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [17]. The participants reported their frequency of consumption of each food item during the previous year on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis. Nutrients were calculated using the Nutritionist IV software (First Databank, San Bruno, CA), modified for Iranian foods.

Assessment of dietary acid load

The measures of dietary acid–base load used were the PRAL, NEAP, and DAL indexes, which were calculated by using individual nutrients derived from the FFQ using the following formulas:

18]

[9]

[19]

Body surface area was calculated using the Du Bois formula: [13, 14]

To calculate PRAL and NEAP, intake data were required for protein, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium. PRAL, DAL, and NEAP scores were derived from the equations of nutrient intakes, and tertiles of the scores were used for statistical analysis.

Muscle strength

Muscle strength was measured by a digital handgrip dynamometer (Saehan, model SH5003; Saehan Corporation, Masan, South Korea). The forearm and wrist of participants were required to be in a normal position, the dynamo-meter grip size was set to the size of their hands; participants were then asked to squeeze the dynamometer handle as hard as possible to exert maximum force. The procedure was repeated three times with each hand, and in total, handgrip strength was measured 6 times. For data analysis, the mean grip strength was calculated using the best attempt from each hand [20].

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 14.) version 25. We analyzed the study participants ‘characteristics according to PRAL, NEAP, and DAL tertiles, using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. ANOVA was used to compare muscle strength across tertiles of the PRAL, NEAP, and DAL. We then used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to adjust for potentially confounding variables, such as age, sex, education, occupation, marriage, living situation, smoking status, fat mass, physical activity, meat consumption, and energy intake. Linear and non-linear regression models were fitted to assess the effect of dietary acid load indicators on muscle strength. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

Results

The general characteristics of participants, across the tertiles of PRAL, NEAP, and DAL, are shown in Table 1. The mean of age and fat-free mass was significantly decreased across tertiles of PRAL, NEAP, and DAL. However, systolic blood pressure was higher in the third tertile of NEAP compared to the first tertile. Those who had greater adherence to all three indices were; married, male, educated, employed, smokers, and had better living situation and metabolic markers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants by tertiles (T) of PRAL, NEAP and DAL

| PRAL | NEAP | DAL | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (1–89) | T2 (90–179) | T3 (180–268) | p | T1 (1–89) | T2 (90–179) | T3 (180–268) | p | T1 (1–89) | T2 (90–179) | T3 (180–268) | p | ||||||||||

| Participants | 89 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 90 | 89 | ||||||||||||

| Characteristics | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age (y) | 41.8 | 13.9 | 34.9 | 11.7 | 33.0 | 12.0 | < 0.001 | 41.7 | 14.0 | 34.2 | 11.3 | 33.8 | 12.4 | < 0.001 | 41.8 | 13.9 | 34.6 | 11.7 | 33.2 | 12.0 | < 0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.7 | 14.7 | 71.4 | 17.8 | 75.1 | 15.4 | 0.22 | 71.6 | 14.6 | 70.0 | 17.2 | 76.6 | 15.3 | 0.01 | 70.7 | 14.5 | 72.1 | 18.0 | 75.3 | 15.3 | 0.14 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 | 4.78 | 24.9 | 4.43 | 25.7 | 4.81 | 0.21 | 26.0 | 4.42 | 24.7 | 4.79 | 26.1 | 4.76 | 0.08 | 25.9 | 4.87 | 25.1 | 4.38 | 25.7 | 4.81 | 0.52 |

| WC (cm) | 81.8 | 11.8 | 88.6 | 13.1 | 90.3 | 12.9 | 0.62 | 89.8 | 11.3 | 87.4 | 13.5 | 91.6 | 12.6 | 0.07 | 89.2 | 11.8 | 89.1 | 13.1 | 90.4 | 12.8 | 0.74 |

| WHR (cm) | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 0.90 | 0.07 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 0.91 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 0.90 | 0.07 | 0.94 |

| Fat-mass (kg) | 23.9 | 9.44 | 21.8 | 8.71 | 21.6 | 10.0 | 0.20 | 23.7 | 8.60 | 21.4 | 9.64 | 22.2 | 9.93 | 0.24 | 23.7 | 9.51 | 22.0 | 8.64 | 21.5 | 10.0 | 0.28 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 47.8 | 11.1 | 49.5 | 12.7 | 53.1 | 13.5 | 0.01 | 47.8 | 11.4 | 48.5 | 11.7 | 54.0 | 13.8 | 0.001 | 47.0 | 10.5 | 50.0 | 13.0 | 53.4 | 13.5 | 0.03 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 114 | 14.5 | 106 | 27.3 | 113 | 10.1 | 0.05 | 112 | 18.2 | 105 | 24.1 | 116 | 11.5 | 0.001 | 114 | 14.3 | 106 | 27.5 | 113 | 10.1 | 0.008 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 70.8 | 11.4 | 70.7 | 12.5 | 70.3 | 7.60 | 0.96 | 70.3 | 11.2 | 69.0 | 11.3 | 72.6 | 9.11 | 0.07 | 70.7 | 11.2 | 70.7 | 12.6 | 70.4 | 7.57 | 0.98 |

| (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 30.3 | 41.1 | 59.6 | 30.3 | 37.8 | 62.9 | 28.1 | 42.2 | 60.7 | ||||||||||||

| Female | 69.7 | 58.9 | 40.4 | 69.7 | 62.2 | 37.1 | 71.9 | 57.8 | 39.3 | ||||||||||||

| Education | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Illiterate | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | ||||||||||||

| Under diploma | 14.6 | 5.6 | 2.2 | 12.4 | 6.7 | 3.4 | 14.6 | 5.6 | 2.2 | ||||||||||||

| Diploma | 21.3 | 17.8 | 16.9 | 22.5 | 18.9 | 14.6 | 21.3 | 17.8 | 16.9 | ||||||||||||

| Educated | 64.0 | 76.7 | 79.8 | 65.2 | 74.4 | 80.9 | 64.0 | 76.7 | 79.8 | ||||||||||||

| Occupation | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Employee | 41.6 | 61.1 | 57.3 | 43.8 | 54.4 | 61.8 | 40.4 | 61.1 | 58.4 | ||||||||||||

| Housekeeper | 31.5 | 7.8 | 10.1 | 28.1 | 13.3 | 7.9 | 31.5 | 7.8 | 10.1 | ||||||||||||

| Retired | 13.5 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 15.7 | 2.2 | 5.6 | 13.5 | 4.4 | 5.6 | ||||||||||||

| Unemployed | 13.5 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 12.4 | 30.0 | 24.7 | 14.6 | 26.7 | 25.8 | ||||||||||||

| Marriage | 0.03 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Single | 25.8 | 47.8 | 55.1 | 24.7 | 45.6 | 58.4 | 25.8 | 48.9 | 53.9 | ||||||||||||

| Married | 67.4 | 50.0 | 41.6 | 68.5 | 50.0 | 40.4 | 67.4 | 48.9 | 42.7 | ||||||||||||

| Divorced | 3.4 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 2.2 | ||||||||||||

| Dead spouse | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||||||

| Living situation | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.02 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alone | 4.5 | 6.7 | 15.7 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 18.0 | 4.5 | 6.7 | 15.7 | ||||||||||||

| With someone | 95.5 | 93.3 | 84.3 | 96.6 | 94.4 | 82.0 | 95.5 | 93.3 | 84.3 | ||||||||||||

| Smoking | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Not smoking | 93.3 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 0.04 | 92.1 | 5.6 | 2.2 | 0.03 | 93.3 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| Quit smoking | 87.8 | 4.4 | 7.8 | 88.9 | 2.2 | 8.9 | 87.8 | 4.4 | 7.8 | ||||||||||||

| Smoking | 78.7 | 6.7 | 14.6 | 78.7 | 7.9 | 13.5 | 78.7 | 6.7 | 14.6 | ||||||||||||

| Metabolic disordersb | |||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 74.2 | 86.7 | 88.6 | 0.02 | 77.5 | 87.8 | 84.1 | 0.17 | 74.2 | 86.7 | 88.6 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| Yes | 25.8 | 13.3 | 11.4 | 22.5 | 12.2 | 15.9 | 25.8 | 13.3 | 11.4 | ||||||||||||

| Activity scorec | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Low | 39.3 | 40.0 | 34.8 | 0.64 | 46.1 | 36.7 | 31.5 | 0.06 | 40.4 | 40.0 | 33.7 | 0.35 | |||||||||

| Moderate | 43.8 | 41.1 | 39.3 | 41.6 | 43.3 | 39.3 | 44.9 | 40.0 | 39.3 | ||||||||||||

| High | 16.9 | 18.9 | 25.8 | 12.4 | 20.0 | 29.2 | 14.6 | 20.0 | 27.0 | ||||||||||||

PRAL Potential renal acid load, NEAP Net endogenous acid production, DAL Dietary acid load, BMI body mass index, WHR waist-hip ratio, WC waist circumference, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, TC total cholesterol

P values result from ANOVA for quantitative variables and χ2 test for qualitative variables

aValues are means ± SD

bMetabolic disorders: Including the history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, respiratory disease and osteoporosis

cActivity score: Data on vigorous and moderate activity and walking for at least 10 min/day during the previous 7 days were recorded according to the IPAQ criteria. Duration and frequency of the days of activity were multiplied by the activity's metabolic equivalent task value for calculating the activity. The total physical activity per week was used to measure the sum of the scores divided into three groups: low, moderate, and high. IPAQ was also measured for a continuous score and stated as an equivalent metabolic (MET)-minutes per week.

Dietary intake of participants for each category of PRAL, NEAP, and DAL are detailed in Additional file 1: Table S1. With increasing tertiles of PRAL, NEAP, and DAL, the mean total energy, grains, red meat, white meat and fish, protein, carbohydrate, and total fat, increased, whilst intake of fruits, vegetables, and potassium decreased.

As detailed in Table 2, in the crude model, there was a significant increase in mean muscle strength of left-hand (MSL), muscle strength of right-hand (MSR), and the mean of the MSL and MSR (MMS) across tertiles of PRAL, NEAP, and DAL. However, after adjustment for confounders, the significant differences were attenuated.

Table 2.

Muscle strength by tertiles (T) of PRAL, NEAP and DAL

| PRAL | NEAP | DAL | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | P | P1 | P2 | P3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | P | P1 | P2 | P3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | P | P1 | P2 | P3 | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||||||||||||

| MSL (kg) | 27.5 ± 10.4 | 28.5 ± 11.1 | 33.3 ± 12.2 | 0.001 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 27.2 ± 10.0 | 28.5 ± 11.1 | 33.6 ± 12.4 | < 0.001 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 26.9 ± 9.88 | 28.9 ± 11.4 | 33.6 ± 12.2 | < 0.001 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.36 |

| MSR (kg) | 30.1 ± 11.6 | 31.0 ± 11.7 | 35.9 ± 12.7 | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 30.1 ± 12.0 | 30.8 ± 11.2 | 36.1 ± 12.7 | 0.002 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 29.4 ± 11.1 | 31.4 ± 11.9 | 36.2 ± 12.7 | 0.001 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.43 |

| MMS (kg) | 28.8 ± 10.8 | 29.8 ± 11.2 | 34.6 ± 12.2 | 0.001 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 28.7 ± 10.8 | 29.6 ± 11.0 | 34.8 ± 12.4 | 0.001 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 28.1 ± 10.3 | 30.1 ± 11.5 | 34.9 ± 12.3 | < 0.001 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.36 |

P1: Adjusted for age, sex, education, occupation, marriage, Living situation, smoking, fat mass and physical activity

P2: Adjusted for age, sex, education, occupation, marriage, Living situation, smoking, fat mass, physical activity and red meat

P3: Adjusted for age, sex, education, occupation, marriage, Living situation, smoking, fat mass, physical activity, red meat and energy intake

PRAL Potential renal acid load, NEAP Net endogenous acid production, DAL Dietary acid load, MSL muscle strength of left hand, MSR muscle strength of right hand; MMS, mean Muscle strength

There were significant relationships between PRAL and MSL (β = 0.24, p < 0.001), MSR (β = 0.23, p < 0.001), and MMS (β = 0.24, p < 0.001). Also, significant associations between NEAP and MSL (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), MSR (β = 0.19, p = 0.002), and MMS (β = 0.20, p = 0.001) were observed. Moreover, we found significant relationships between DAL and MSL (β = 0.25, p < 0.001), MSR (β = 0.23, p < 0.001), and MMS (β = 0.24, p < 0.001). After controlling for potential confounders, there was no significant association (Additional file 1: Table S2).

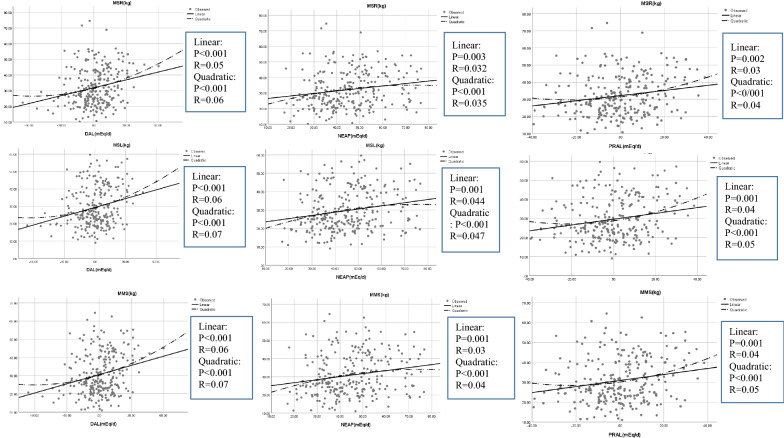

There was a significant nonlinear relationship between dietary acid load indicators and muscle strength (p < 0.001), where muscle strength increased with increasing dietary acid load indicators (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Association of dietary acid load indices and muscle strength

Discussion

In the present study, we found a significant positive association between indicators of dietary acid load and muscle strength. However, these associations were not significant after adjustment for confounding variables. In non-linear regression model, a higher dietary acid load was associated with greater muscle strength.

Higher consumption of foods rich in animal protein, such as meat, cheese, eggs, and, grains increases the production of acid in the body. This study indicates that with increasing dietary acid load, intakes of grains, dairy, red meat, and white meat and fish were increased. They are associated with the production of hydrogen sulfate that arises from sulfur-containing amino acids, and phosphoric acid from phospholipids, which consequently increases dietary acid load. Consistent with our results, Masuki et al. inferred that a high intake of milk products after exercise yielded a significant increase in thigh muscle strength [21]; Contrastingly, Alemán-Mateo et al. in a randomized clinical trial of sarcopenic elderly men and women over 60 years, showed that adding 210 g/day of ricotta cheese to their habitual diet yielded no significant change in total appendicular skeletal muscle. It appears that the amount of protein intake may have an effect on sarcopenic status in the elderly. However, in Alemán-Mateo et al. handgrip strength improved following consumption of protein-rich foods, which suggests that the loss of skeletal muscle in elderly men may be reversed, or ameliorated, by adding protein-rich foods, such as ricotta cheese, to the diet [22].

In our study, the intake of meat increased across tertiles of PRAL, NEAP, and DAL. Red meat is a high-quality source of protein containing some compounds that can influence protein metabolism, such as some minerals (iron and zinc), vitamins (mainly B group vitamins) [23], creatine [24], carnitine, carnosine, and conjugated linoleic acid [25], in addition, it also contains complete sufficient essential amino acids to promote the synthesis of skeletal muscle proteins, and to preserve skeletal muscle mass [26, 27]. In line with our findings, Symons et al. asserted that a moderate intake of lean meat can improve synthesis of protein in both genders [28]. In contrast, in a sample of older adults, Granic et al. reported that dietary patterns high in red meat, would adversely influence muscle strength [29]. It has been putatively hypothesized that this may be related to the impact of adverse acid–base equilibrium on muscle strength [30, 31], and the adverse effects of arachidonic acid (AA) on muscle size, due to increased expression and activation of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, which may trigger muscle protein degradation [32]. It is conceivable that our results may be influenced by the mediating effect of protein. Morton RW, et al. in a meta-analysis, concluded that post-exercise protein intake, combined with resistance exercise training (RET), can lead to increases in muscle mass, fat-free mass, muscle size, and strength [8]. Indeed, empirical studies have suggested that such improvements may be due to the effects of protein on muscle hypertrophy and function, whilst it has also been reported that ingestion of 20–30 g or 0.25–0.30 g/kg protein after resistance exercise training, with habitual protein intakes at ~ 1.6 g/kg/day stimulates muscle adaptations to exercise training [8].

In contrast with our findings, Neville et al. found that greater fruit and vegetable consumption can yield increases grip strength, however, the period of their study was short [33]. Dawson-Hughes et al. also found that higher alkaline dietary load, is positively associated with muscle mass indices [30]; however, this association was weak, and after controlling for the percentage of protein intake, became weaker.

The exact mechanism through which an alkalotic diet can affect muscle mass and strength is not completely understood. Studies suggest that, although protein is essential for muscle mass conservation [34, 35], other nutrients in the alkalinogenic foods, included potassium, magnesium [33, 36], antioxidants, and carotenoid content, may protect against oxidative stress and inflammation [37, 38].

Conclusion

we found a significant positive association between a higher dietary acid loads and greater muscle strength. Further studies are needed to confirm the veracity of our findings.

Limitations

As with any cross-sectional study design, no causal associations can be determined, and although we adjusted for possible confounders, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding variables.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Dietary intakes of participants by tertiles(T) of PRAL, NEAP and DAL. Table S2. Multiple linear regression between muscle strength and indexes of dietary acid load.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the subjects who participated in the study.

Abbreviations

- PRAL

Potential renal acid load

- NEAP

Net endogenous acid production

- DAL

Dietary acid load

- MSL

Mean muscle strength of left-hand

- MSR

Muscle strength of right-hand

- MMS

Mean muscle strength

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- WC

Waist circumference

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- FBS

Fasting blood glucose

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein

- TG

Triglyceride

- IPAQ

International physical activity questionnaire

- FFQ

Food frequency questionnaire

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- SFA

Saturated fatty acid

- MUFA

Monounsaturated fatty acid

- AA

Arachidonic acid

- SMM

Skeletal muscle mass

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

Authors’ contributions

SS-b and Kdj contributed in conception and design of the study. SD participated in acquisition of data. SM and SS-b contributed to data analysis and data interpretation, SM, SS-b and FD participated in manuscript drafting, SS-b and CC finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Since the privacy of research participants may be compromised, we cannot make the information publicly available.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants signed a written informed consent and the study was approved by Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (IR. TUMS.VCR.REC. 1398.503).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All of authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Saba Mohammadpour, Email: Saba_mp@yahoo.com.

Farhang Djafari, Email: farhangj74@gmail.com.

Samira Davarzani, Email: samira.davarzani@yahoo.com.

Kurosh Djafarian, Email: kdjafarian@tums.ac.ir.

Cain C. T. Clark, Email: cain.clark@coventry.ac.uk

Sakineh Shab-Bidar, Email: s_shabbidar@tums.ac.ir.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13104-020-05309-6.

References

- 1.Gaines JM, Talbot LA. Isokinetic strength testing in research and practice. Biol Res Nurs. 1999;1(1):57–64. doi: 10.1177/109980049900100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt M, Schwartz AV, Simonsick EM, Tylavsky FA, Visser M, Newman AB. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(10):1059–1064. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu F, Wills K, Laslett LL, Oldenburg B, Jones G, Winzenberg T. Associations of dietary patterns with bone mass, muscle strength and balance in a cohort of Australian middle-aged women. Br J Nutr. 2017;118(8):598–606. doi: 10.1017/s0007114517002483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breen L, Phillips SM. Skeletal muscle protein metabolism in the elderly: interventions to counteract the 'anabolic resistance' of ageing. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011;8:68. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Carvalho DHT, Scholes S, Santos JLF, de Oliveira C, Alexandre TDS. Does abdominal obesity accelerate muscle strength decline in older adults? Evidence from the english longitudinal study of ageing. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(7):1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen HT, Wu HJ, Chen YJ, Ho SY, Chung YC. Effects of 8-week kettlebell training on body composition, muscle strength, pulmonary function, and chronic low-grade inflammation in elderly women with sarcopenia. Exp Gerontol. 2018;112:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daly RM, O'Connell SL, Mundell NL, Grimes CA, Dunstan DW, Nowson CA. Protein-enriched diet, with the use of lean red meat, combined with progressive resistance training enhances lean tissue mass and muscle strength and reduces circulating IL-6 concentrations in elderly women: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(4):899–910. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.064154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morton RW, Murphy KT, McKellar SR, Schoenfeld BJ, Henselmans M, Helms E, Aragon AA, Devries MC, Banfield L, Krieger JW, Phillips SM. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(6):376–384. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frassetto LA, Todd KM, Morris RC, Jr, Sebastian A. Estimation of net endogenous noncarbonic acid production in humans from diet potassium and protein contents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68(3):576–583. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.3.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwalfenberg GK. The alkaline diet: is there evidence that an alkaline pH diet benefits health? J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:727630–727630. doi: 10.1155/2012/727630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welch AA, MacGregor AJ, Skinner J, Spector TD, Moayyeri A, Cassidy A. A higher alkaline dietary load is associated with greater indexes of skeletal muscle mass in women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(6):1899–1908. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frassetto L, Lanham-New S, Macdonald H, Remer T, Sebastian A, Tucker K, Tylavsky F. Standardizing terminology for estimating the diet-dependent net acid load to the metabolic system. J Nutr. 2007;137:1491–1492. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.6.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du Bois D, Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known 1916. Nutrition. 1989;5(5):303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verbraecken J, Van de Heyning P, De Backer W, Van Gaal L. Body surface area in normal-weight, overweight, and obese adults. A comparison study. Metabolism. 2006;55(4):515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiavo L, Scalera G, Pilone V, De Sena G, Iannelli A, Barbarisi A. Fat mass, fat-free mass, and resting metabolic rate in weight-stable sleeve gastrectomy patients compared with weight-stable nonoperated patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(10):1692–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.I.R.C.J.h.w.i.k.s.s., Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)-short and long forms. 2005.

- 17.Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Azadbakht L, Hu FB, Willett WC. Dietary patterns and markers of systemic inflammation among Iranian women. J Nutr. 2007;137(4):992–998. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Remer T, Dimitriou T, Manz F. Dietary potential renal acid load and renal net acid excretion in healthy, free-living children and adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(5):1255–1260. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Remer T, Manz F. Potential renal acid load of foods and its influence on urine pH. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95(7):791–797. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(95)00219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaz M, Thangam S, Prabhu A, Shetty PS. Maximal voluntary contraction as a functional indicator of adult chronic undernutrition. Br J Nutr. 1996;76(1):9–15. doi: 10.1079/bjn19960005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masuki S, Nishida K, Hashimoto S, Morikawa M, Takasugi S, Nagata M, Taniguchi SI, Rokutan K, Nose H. Effects of milk product intake on thigh muscle strength and NFKB gene methylation during home-based interval walking training in older women: a randomized, controlled pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0176757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alemán-Mateo H, Macías L, Esparza-Romero J, Astiazaran-García H, Blancas AL. Physiological effects beyond the significant gain in muscle mass in sarcopenic elderly men: evidence from a randomized clinical trial using a protein-rich food. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:225–234. doi: 10.2147/cia.S32356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rondanelli M, Perna S, Faliva MA, Peroni G, Infantino V, Pozzi R. NOVEL insights on intake of meat and prevention of sarcopenia: all reasons for an adequate consumption. Nutr Hosp. 2015;32(5):2136–2143. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.32.5.9638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moon A, Heywood L, Rutherford S, Cobbold C. Creatine supplementation: can it improve quality of life in the elderly without associated resistance training? Curr Aging Sci. 2013;6(3):251–257. doi: 10.2174/1874609806666131204153102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman M, Halade GV, El Jamali A, Fernandes G. Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) prevents age-associated skeletal muscle loss. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383(4):513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young JF, Therkildsen M, Ekstrand B, Che BN, Larsen MK, Oksbjerg N, Stagsted J. Novel aspects of health promoting compounds in meat. Meat Sci. 2013;95(4):904–911. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams P. Nutritional composition of red meat. Nutr Dietetics. 2007;64:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0080.2007.00197.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Symons TB, Schutzler SE, Cocke TL, Chinkes DL, Wolfe RR, Paddon-Jones D. Aging does not impair the anabolic response to a protein-rich meal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(2):451–456. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.2.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Granic A, Jagger C, Davies K, Adamson A, Kirkwood T, Hill TR, Siervo M, Mathers JC, Sayer AA. Effect of dietary patterns on muscle strength and physical performance in the very old: findings from the newcastle 85+ study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0149699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Ceglia L. Alkaline diets favor lean tissue mass in older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(3):662–665. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan R, Leung J, Woo J. Association between estimated net endogenous acid production and subsequent decline in muscle mass over four years in ambulatory older chinese people in hong kong: a prospective cohort study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(7):905–911. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitehouse AS, Khal J, Tisdale MJ. Induction of protein catabolism in myotubes by 15(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid through increased expression of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(4):737–745. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neville CE, Young IS, Gilchrist SE, McKinley MC, Gibson A, Edgar JD, Woodside JV. Effect of increased fruit and vegetable consumption on physical function and muscle strength in older adults. Age (Dordr) 2013;35(6):2409–2422. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9530-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wackerhage H, Rennie MJ. How nutrition and exercise maintain the human musculoskeletal mass. J Anat. 2006;208(4):451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng X, Zhu K, Devine A, Kerr DA, Binns CW, Prince RL. A 5-year cohort study of the effects of high protein intake on lean mass and BMC in elderly postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(11):1827–1834. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manini TM, Clark BC. Dynapenia and aging: an update. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(1):28–40. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mecocci P, Fanó G, Fulle S, MacGarvey U, Shinobu L, Polidori MC, Cherubini A, Vecchiet J, Senin U, Beal MF. Age-dependent increases in oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins in human skeletal muscle. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(3–4):303–308. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cesari M, Pahor M, Bartali B, Cherubini A, Penninx BW, Williams GR, Atkinson H, Martin A, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Antioxidants and physical performance in elderly persons: the Invecchiare in Chianti (InCHIANTI) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(2):289–294. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Dietary intakes of participants by tertiles(T) of PRAL, NEAP and DAL. Table S2. Multiple linear regression between muscle strength and indexes of dietary acid load.

Data Availability Statement

Since the privacy of research participants may be compromised, we cannot make the information publicly available.